Extrinsic factors such as habitat loss and degradation,exploitation, invasive species, disease, pollution, and intrinsic factors associated with reproduction and growth rates are generally implicated as the causal factors in the current decrease in biodiversity. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) (2010b), habitat loss and degradation are the most important factors influencing mammals,birds, amphibians, and gymnosperms; however, the importance of other factors varies profoundly depending on the taxa examined. The IUCN (2010a) has recently reported that although diseases and pollution greatly in fluence amphibians, and invasive species are a profound influence in the bird population, these same factors exert only a minimal influence on the diversity of gymnosperms. Therefore, without proper knowledge of the factors influencing each species and the extent of such influences, conservation efforts will be difficult to devise and implement successfully. For example, if the species is naturally rare (e.g., geographically limited distribution, small populations, and small habitat requirements), it requires twice the habitat size of a species that is rare as the result of human activities (e.g., forest disturbance, traditional cultivation, and collection activities) (Vellak et al. 2009). The factors mentioned above illustrate that the principal causal factors leading rare species to the brink of extinction are largely associated with the ecology of species. However, thus far, ecological concepts have not been applied to the process of listing and managing rare or endangered species in Korea.

Since habitat loss and degradation are the primary factors responsible for the extinction of species of diverse taxa, the IUCN (1993) has established the objective of conserving 10% of land in each country. Rapid industrialization and urbanization, post-1970s, has caused some real problems, such as the fragmentation of ecosystems, destruction of landscapes, and pollution. For example, the proportion of forests--the main habitat of many endangered species--has been declining 0.16% every year since the 1970s (Chang and Seok 1997). The national parks of Korea account for 80% of all conservation areas and represent relatively well-preserved natural systems. However, the mountain range that runs through most of the length of the Korean Peninsula, in which most of the national parks are located, is interrupted every 8.3 km, by a total of 82 roads (61 paved roads and 21 non-paved roads) (Green Korea United 2008). Thus, even the national parks are not truly safe from habitat loss and degradation. This, in combination with the fact that climate changes require dynamic conservation strategies (Mawdsley et al. 2009), illustrates the urgent need to evaluate the locations and sizes of conservation areas in relation to the distributions of endangered species.

IUCN’s guidelines for using the IUCN Red List categories and criteria (ver. 3.1) divide the extant species into 6 groups depending on the degree of their endangerment (i.e., reduction of their population size, current population size, geographic range, and extinction probabilities). On the other hand, endangered species and species in need of special care have been adjusted to class I and II, respectively, by an amendment to the Korean Wildlife Protection Act (Ministry of Environment 2006). Class I endangered wild animals and class I plants are species whose populations have been drastically reduced, thus leading to their endangerment, and class II includes species that are under threat of endangerment if the threatening factors are not removed or relieved. However, several authors (Kim 1994, Bang and Ahn 2005, Chang et al. 2005) claim that the Ministry of Environment’s definitions are quite ambiguous. The lack of clarity in these definitions means that even if a species is designated as endangered, specific management and conservation strategies, as well as showing proof of release from endangerment, will be problematic. Another problem we are currently experiencing is that most endangered species have been defined as endangered on the basis of their ornamental or economic value, rather than on the basis of Korean biodiversity. Furthermore, there has been no confirmation on the proportion of current conservation areas that function as habitats for the endangered species, despite the fact that habitat conservation is a key factor in the maintenance of biodiversity.

A number of activities targeted toward the conservation and restoration of endangered animals and plants will be attempted, with a focus on existing national parks (Ministry of Environment 2008). However, in order to maintain the evolutionary potential of endangered species, if possible, conservation efforts must be conducted

>

Factors causing species endangerment

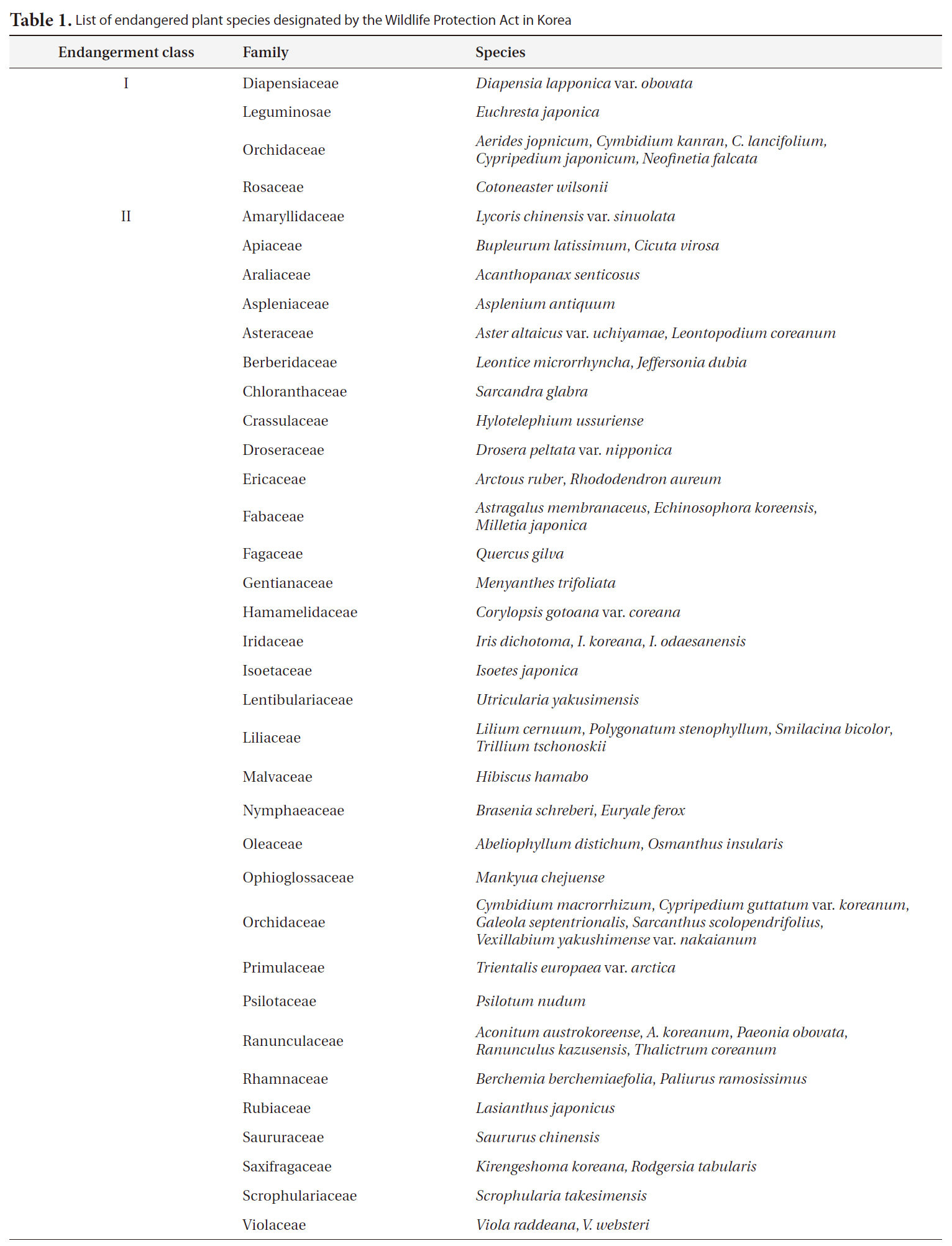

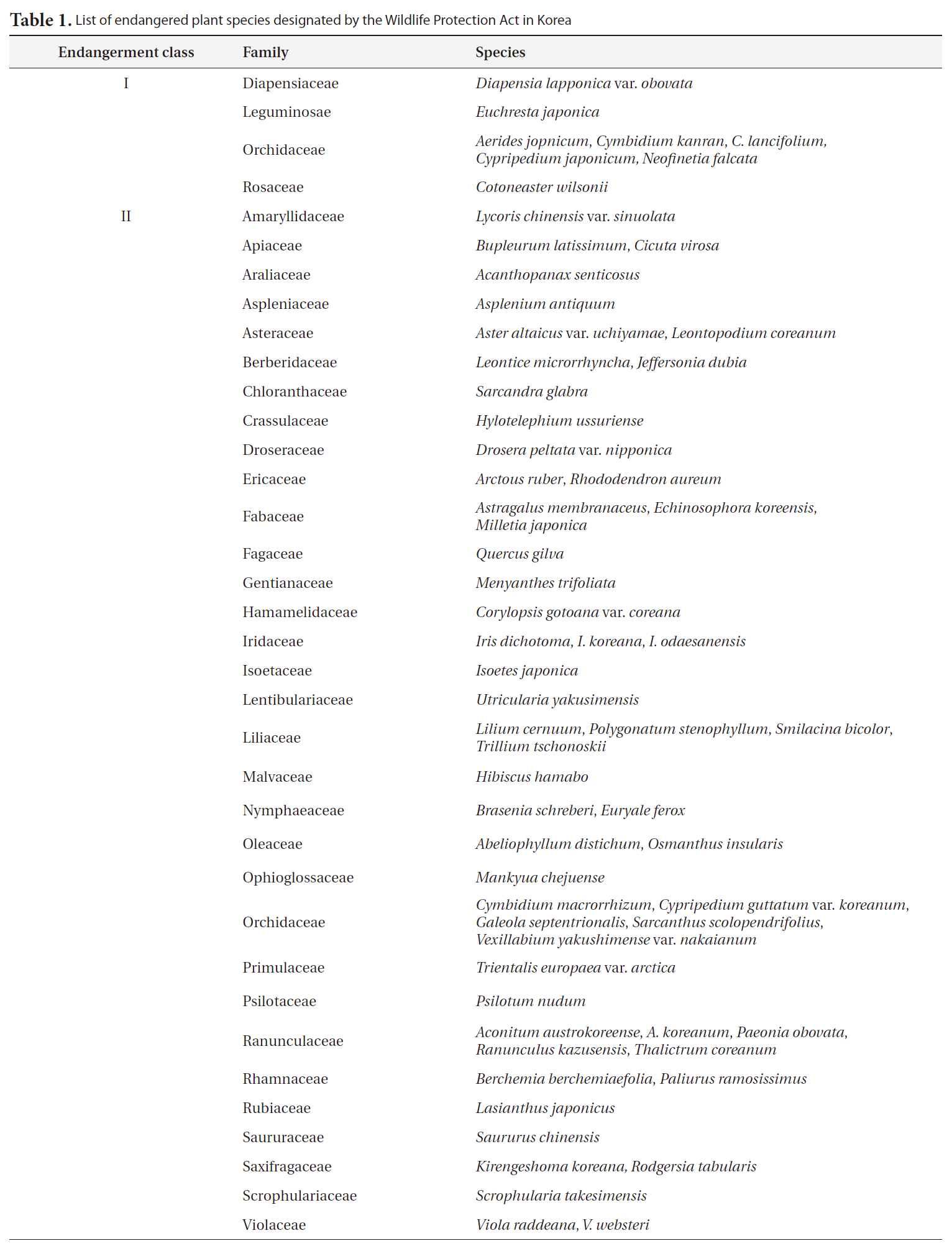

The Wildlife Protection Act of Korea, which was first enforced in 2005, designated a total of 64 plant species (8 and 56 species in classes I and II, respectively) as endangered species (Table 1). We collected information from various papers (e.g., Hyun 2002, Chang et al. 2005), the internet, and news articles, on threatened or endangered

[Table 1.] List of endangered plant species designated by the Wildlife Protection Act in Korea

List of endangered plant species designated by the Wildlife Protection Act in Korea

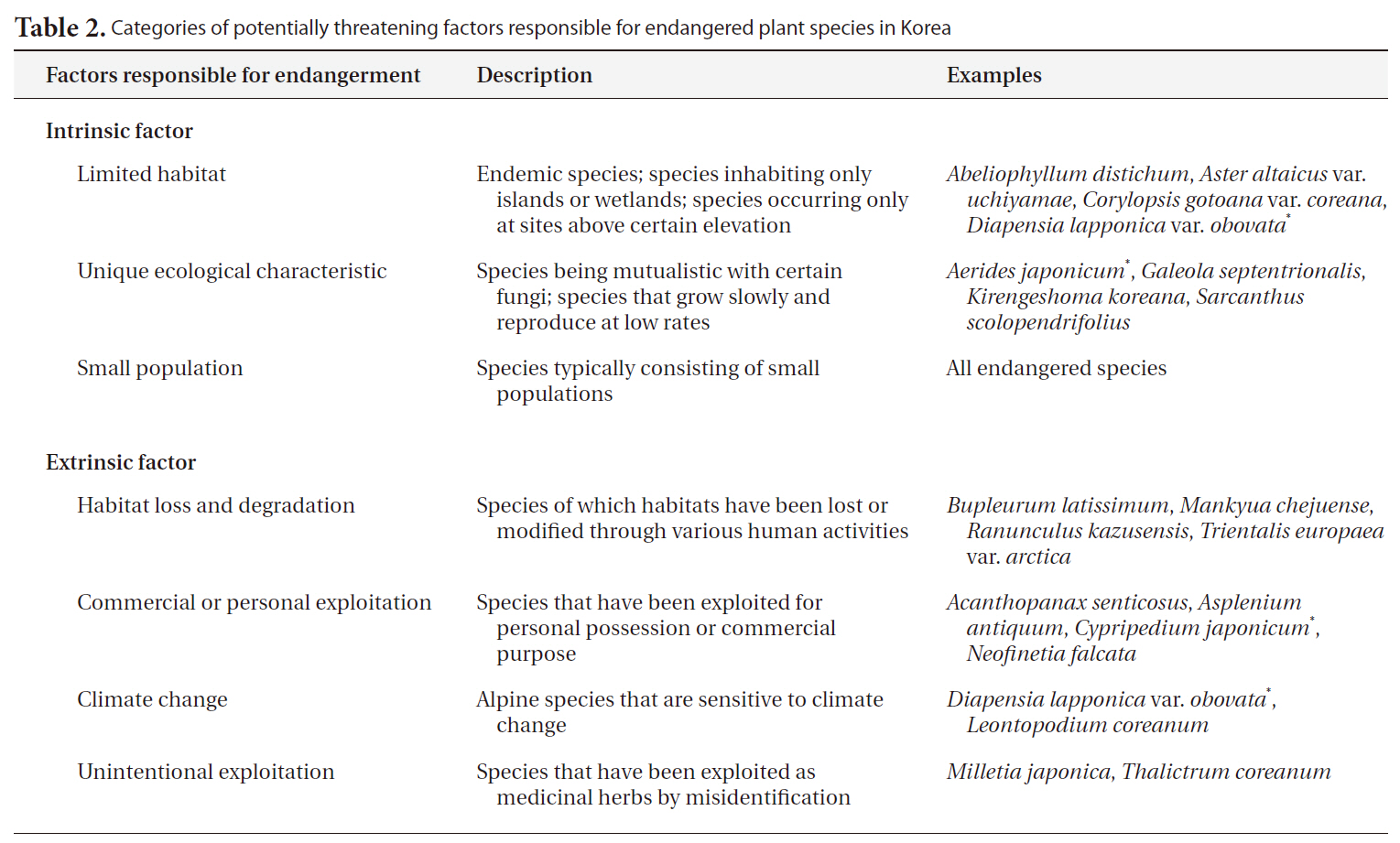

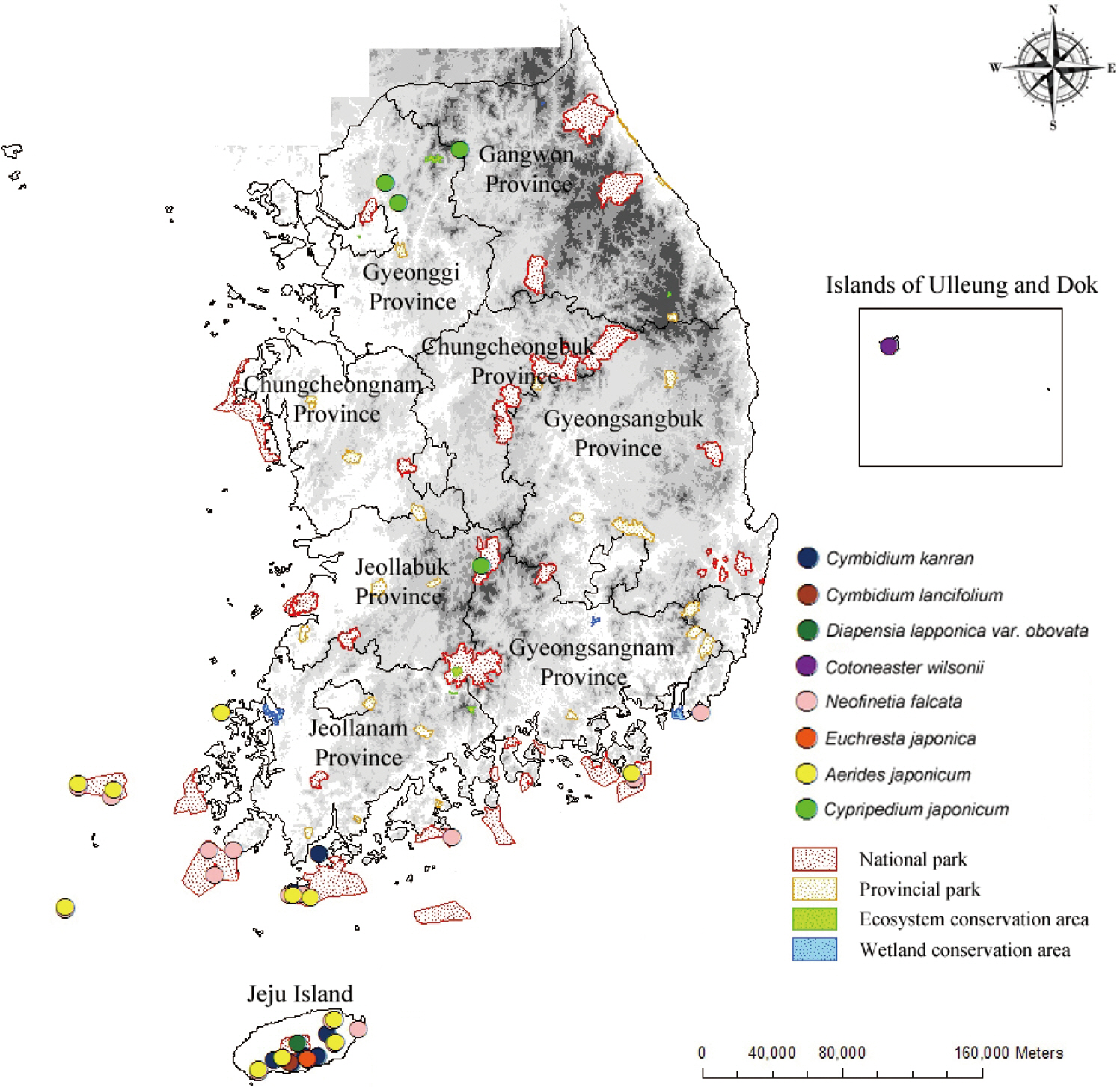

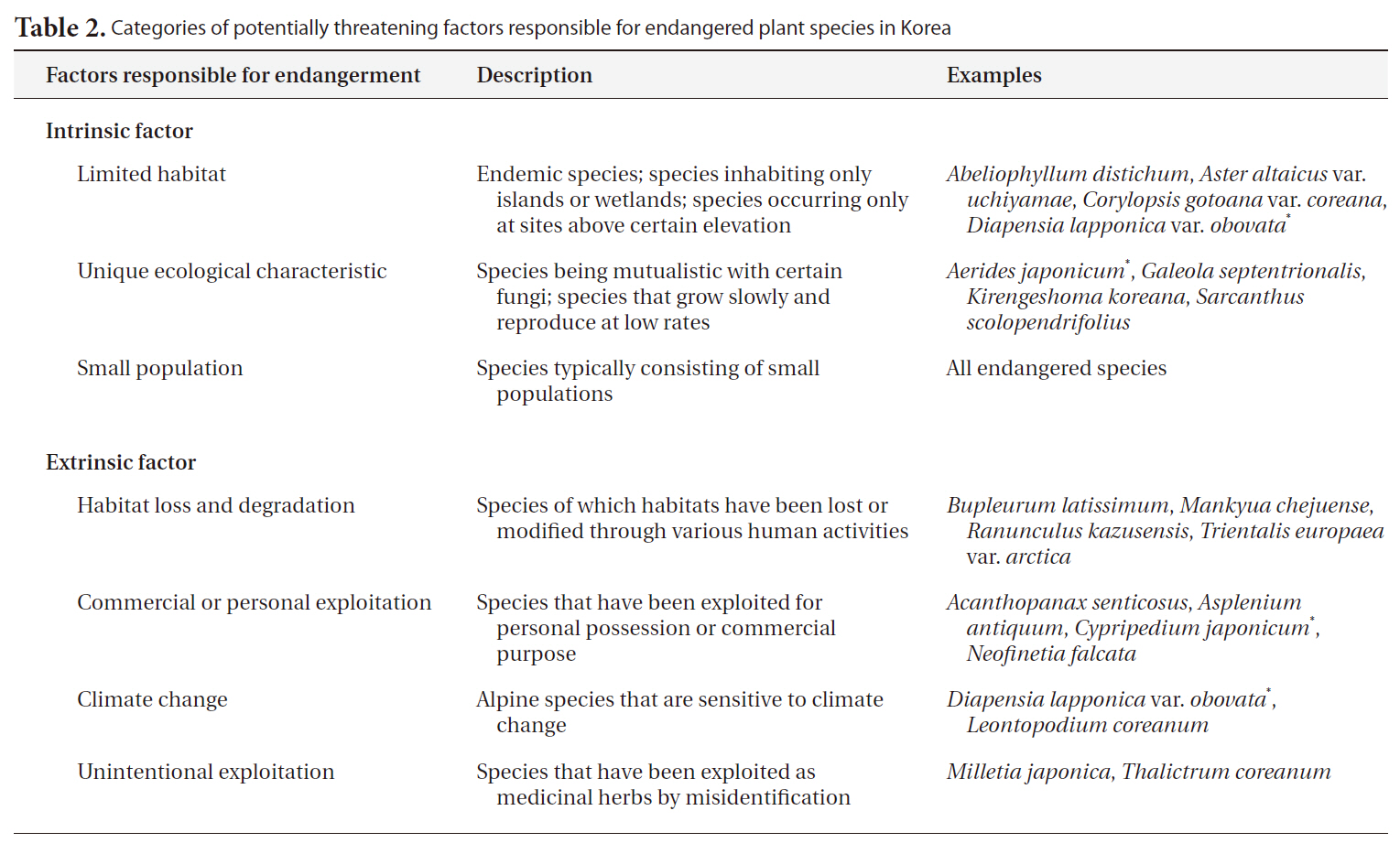

species, and the potentially dangerous factors threatening endangered species. In an attempt to identify the extent to which endangered species are endemic, we also acquired information regarding the endemism of endangered species from the Ministry of Environment (2005a). We categorized these factors via a slight modification of Groom’s method (2005) (Table 2). First, we divided the factors into intrinsic and extrinsic factors (Table 2). The intrinsic factors include 1) limited habitats, 2) unique ecological characteristics, and 3) small population sizes. Small population may be the cause or result of endangerment; however, as there was no historical evidence for a reduction in population size, we determined that population size is an intrinsic factor that result in species endangerment. Small population size was applied to all 64 endangered plant species. Extrinsic factors are attributable to human activities and natural catastrophes, and include 1) habitat loss and degradation, 2) commercial or personal exploitation, 3) climate change, and 4) unintentional exploitation. It is more common for species to become endangered as the result of several factors, as opposed to a single factor. For example, in the case of

Categories of potentially threatening factors responsible for endangered plant species in Korea

of factors that cause endangerment is far greater than the total number of species investigated.

>

Habitats of endangered plant species in Korea

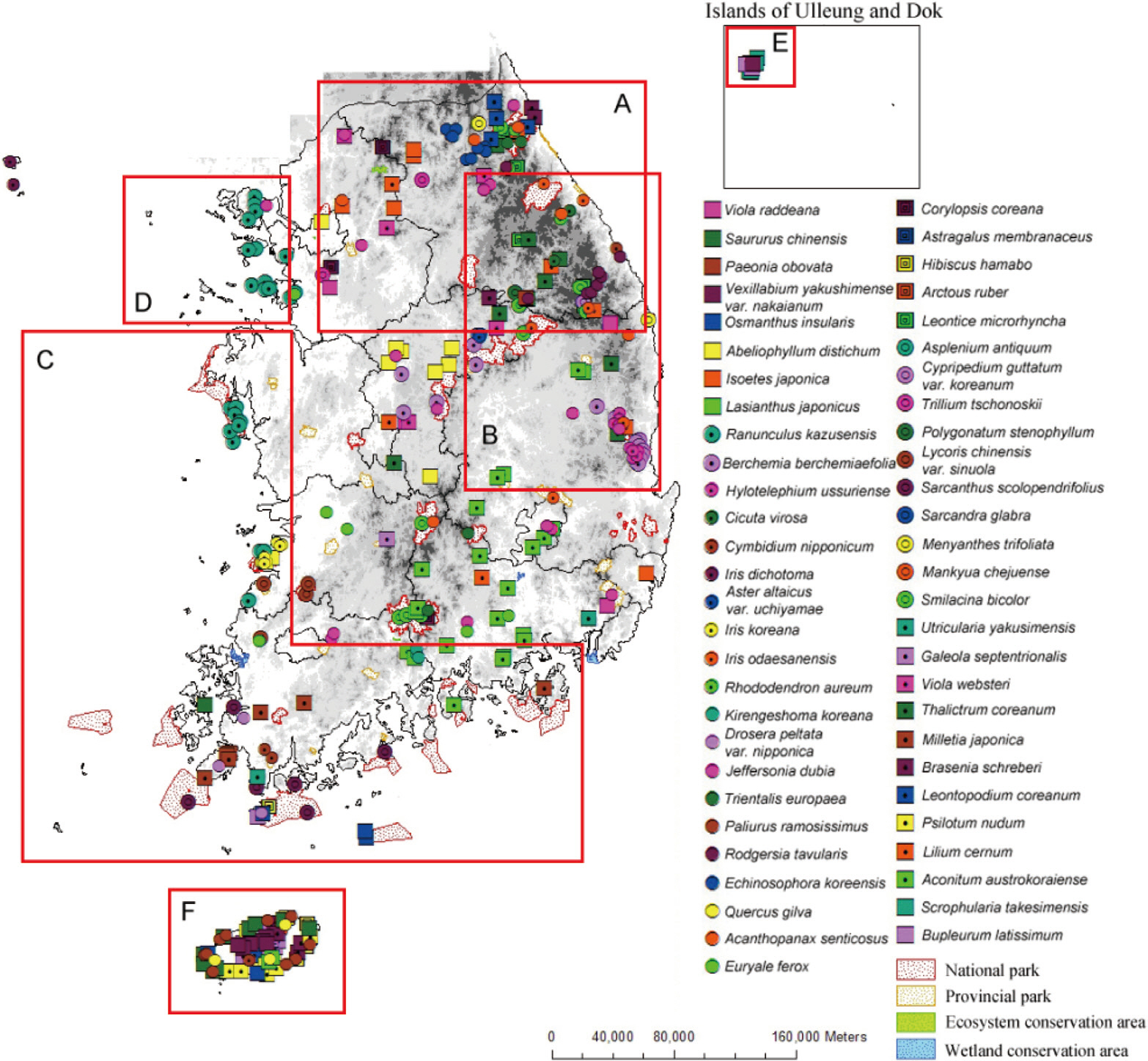

We used 1:40,000 scale digital maps of Korea to evaluate the correlation between the distributions of endangered plant species and protected conservation areas (national parks, provincial parks, ecosystem conservation areas, and wetland conservation areas), and to confirm gap areas. Based on the biotic resources distribution map (Ministry of Environment 2005c), we digitized the habitats occupied by endangered plant species. Habitat information obtained after 2003 was expressed as points. When the habitat information obtained from various sources was not sufficiently precise, we noted the information as points on the administrating agencies governing the area, such as the town hall.

National parks, provincial parks, ecosystem conservation areas, and wetland conservation areas were defined as protected conservation areas. Information regarding the location and size of these areas was collected (Ministry of Environment 2003, 2007, National Parks of Korea 2009). Korean digital elevation map (DEM) data, maps of national rivers and class I regional rivers (National Geographic Information Institute 2003), along with the maps of all protected conservation areas, were combined with the maps of endangered plant species, and subsequently edited. ArcView3.2 and ArcMap ver 9.0 (Environmental Systems Research Institute 2004) were used for analysis.

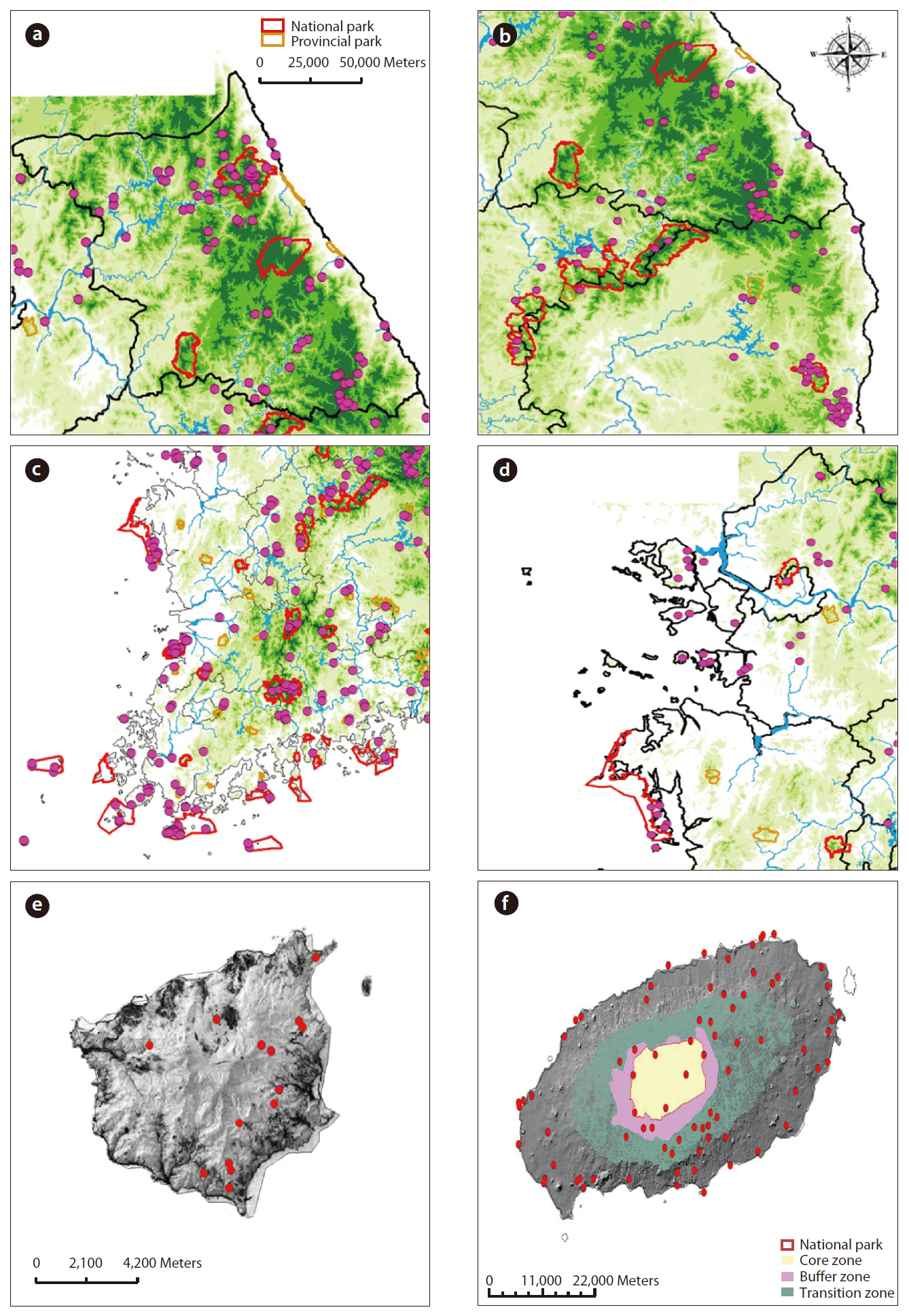

We assessed the overall pattern of habitat distribution of endangered plant species by combining all of the maps onto eight map layers. We then narrowed our focus to the Gangwon Province and islands such as Gangwha, Ulleung, and Jeju (Jeju Province), where the endangered species’ habitats were concentrated. For Jeju Island, the zoning imposed by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)’s Programme on Man and the Biosphere (MAB) was also taken into consideration. We screen-digitized and converted the surface zoning data (core, buffer, and transition areas) into polygon data. Digital maps of Hallasan National Park and other conservation areas were then combined with the maps of endangered species’ habitats. We magnified Gangwon Province and Gangwha Island from the overall map and confirmed the locations of the species. Finally, we enlarged the island of Ulleung based on the satellite images provided by Ministry of Environment (2005b) and saved it as a TIFF file. We then combined this with a habitat map of the endangered species, thus generating individual data.

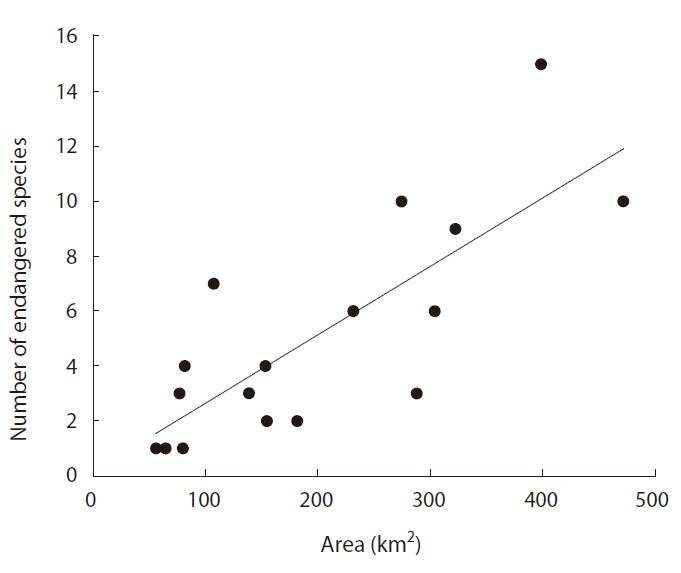

In order to evaluate the relationship between the size of conservation areas and the numbers of endangered species, we conducted a regression analysis for 17 national parks (excluding three seashore and marine national parks, i.e., Taeanhaean, Dadoehaehaesang, and Hallyeohaesang National Parks, out of 20 national parks) located on land. Because the majority of conservation areas are national parks, the remainder of the conservation areas, i.e., provincial parks, ecosystem conservation areas, and wetland conservation areas, were described as secondary conservation areas.

After analyzing the factors that can cause species endangerment, the principal intrinsic factors were determined as “small population” (64 species) and “limited habitat” (40 species). The most common extrinsic factors were “commercial or personal exploitation” (39 species), and “habitat loss and degradation” (26 species) (Fig. 1). Therefore, when treating small population as an intrin-

sic factor, intrinsic factors were determined to affect the species more profoundly than extrinsic factors (39% vs. 61%). Excluding small population, limited habitat and commercial or personal exploitation were the most threatening factors, followed by habitat loss and degradation. Thus, excluding small population, we found that 1.5 times more species were influenced by extrinsic factors than by intrinsic factors.

>

Size of protected conservation areas

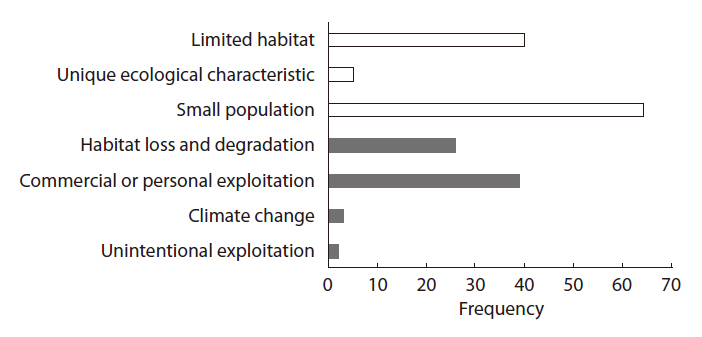

Among all conservation areas (4,850.498 km2) in Korea, the size of national parks (excluding three seashore and marine national parks) totaled 3,898.948 km2, which is 80% of all the conservation areas, and 3.9% of the country’s land (Fig. 2). The rest of the conservation areas included 21 provincial parks (769.5 km2), 12 ecosystem conservation areas (102.04 km2), and 7 wetland conservation areas (80.01 km2). The total conservation areas amounted to 4.9% of the country’s land. The mean size of the national parks (X = 229.3 km2) was far larger than that of the secondary conservation areas: provincial park (X = 36.6 km2), ecosystem conservation area (X = 8.5 km2), and wetland conservation area (X = 11.4 km2).

>

Distribution of endangered plant species

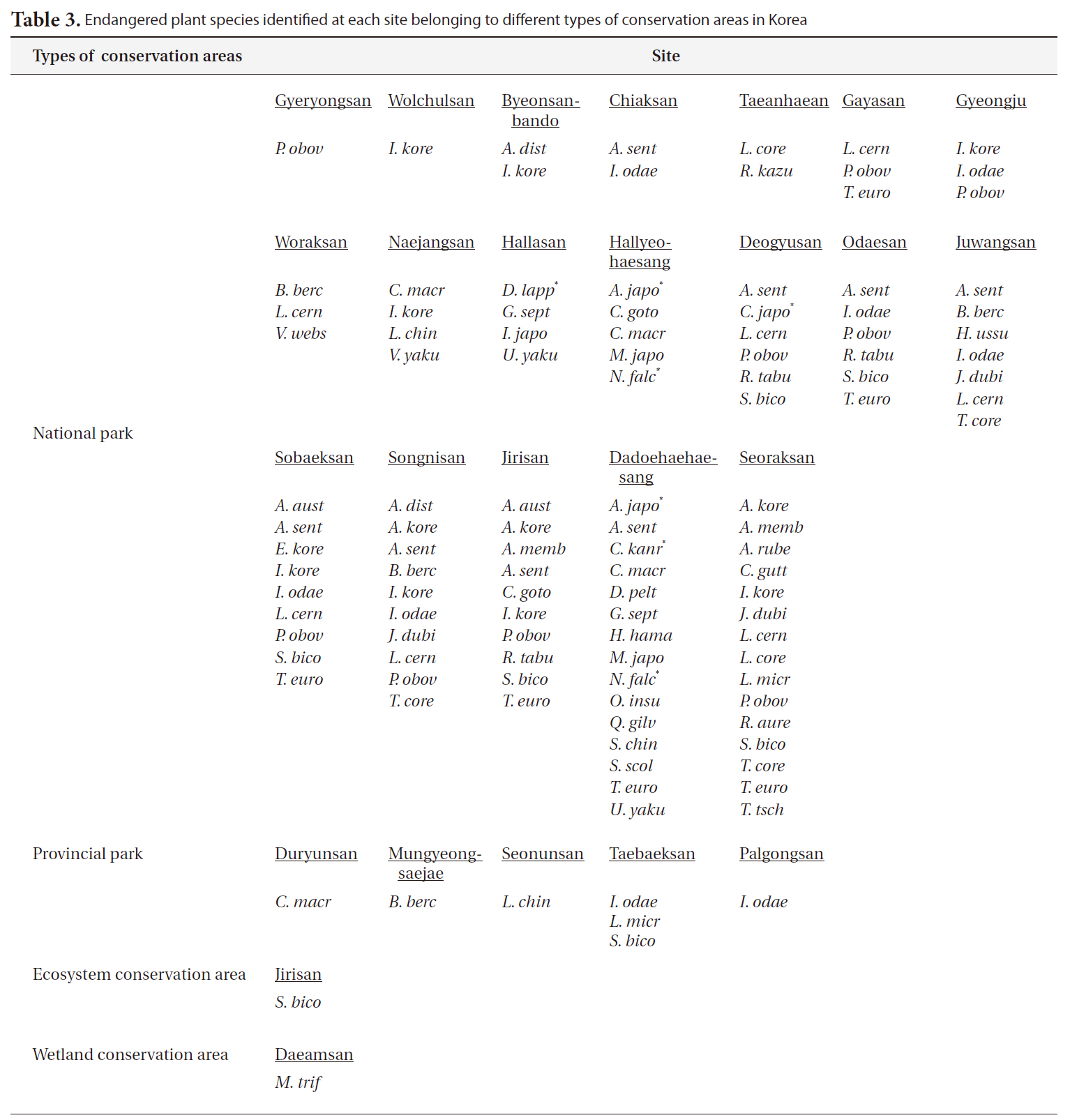

At the species level, 69% (5 and 39 species in class I and II, respectively) of the endangered plant species were distributed throughout 20 national parks (Figs. 2 and 3). The number of endangered species increased with the size of the national parks (Fig. 4). For example, large national parks such as Jirisan (471.8 km2), Seoraksan (398.5 km2) and Songnisan (274.5 km2) National Parks included more than ten endangered species, whereas smaller parks such as Wolchulsan (56.1 km2) and Gyeryongsan (64.7 km2) National Parks included only a single endangered spe-

cies each. The national parks differed from one another not only in the number of endangered species but also in the species identities (Table 3). A total of 20 species such as

At the habitat level, class I species usually appeared on the southern coast of the peninsula and Jeju Island, and class II species were distributed more broadly (Figs. 2 and 3). However, depending on the endangered species, profound differences in habitat distribution were observed. Endangered species such as

Endangered species distributions were focused largely

in unprotected areas, particularly in the mountain regions of Gangwon Province and Gyeongsangbuk Province, the southwestern coast, and islands including Gangwha, Jeju, and Ulleung. In the Gangwon Province,

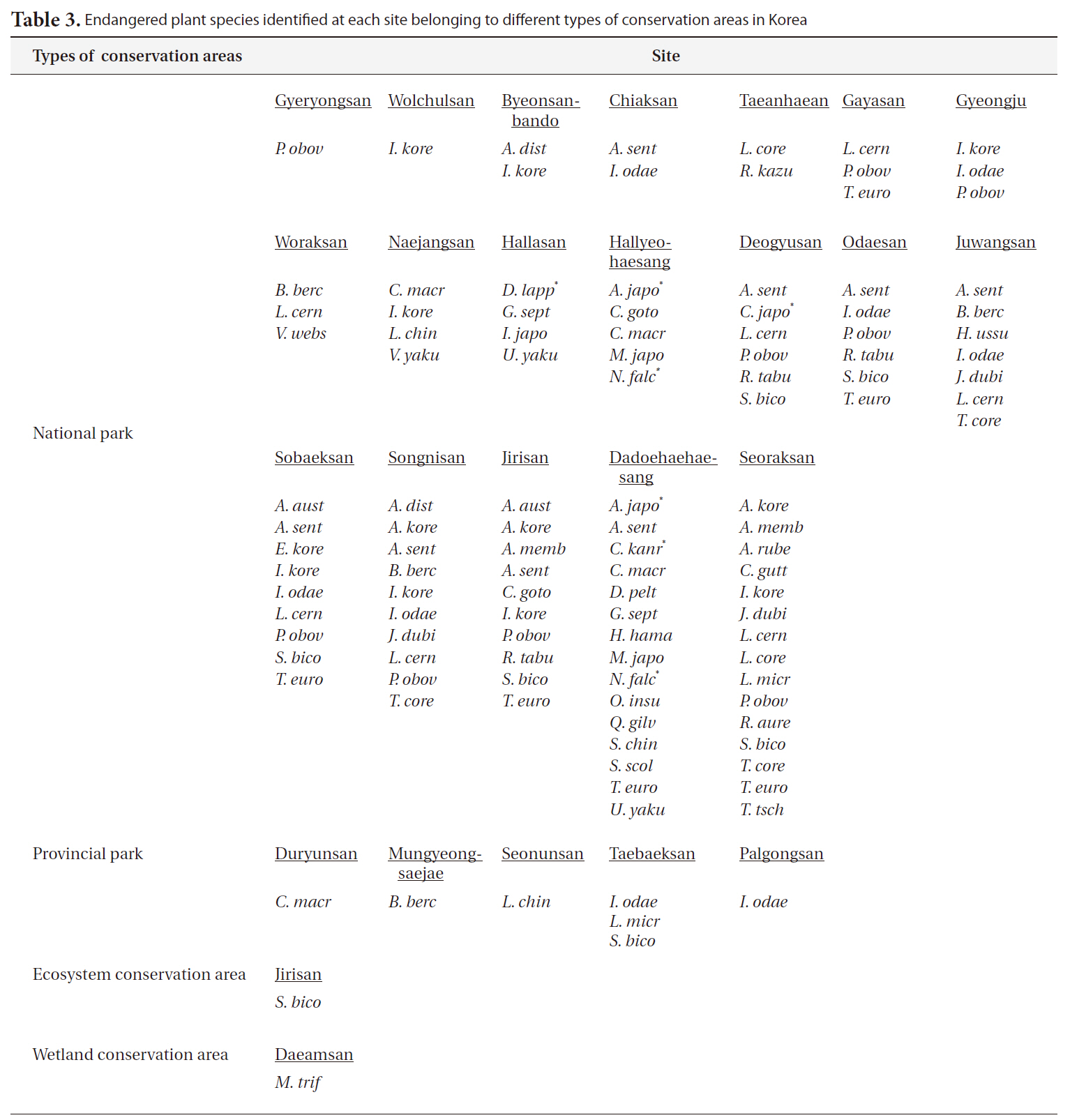

Endangered plant species identified at each site belonging to different types of conservation areas in Korea

Youngheung islands (Fig. 5d). On Ulleung Island, which has never been connected to land, endemic species such as

On Jeju Island, there were a total of 22 endangered species making the island their habitat. They included the following: six class I species (

Although the distribution of endangered or threatened species has been examined sporadically (e.g., Hyun 2002), this study is the first to report on the potential causes responsible for the endangerment of plant species in Korea. Excluding the small population category, endangered plant species in Korea are more frequently associated with extrinsic factors than with intrinsic factors. This result is consistent with a number of previous studies in which the influence of cropland expansion and urbanization on species endangerment and extinction was emphasized (e.g., Vitousek et al. 1997, Wilcove et al. 1998, Czech et al. 2000, Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities, Australian Government 2005). On the other hand, the endangerment of species appears to be related weakly to unique ecological characteristics. However, considering the fact that the biology of endangered and native species is currently not well known, the small effects of ecological characteristics are more likely a result of a lack of information than any absence of effects of ecological characteristics. As species differ in their response to environmental changes, endangered species conservation can only be appropriately achieved when we understand the types of past threats to those species.

Recently, Noss et al. (2009) reported that 28.6% of the vascular plant species in United States are critically imperiled, imperiled, or vulnerable species, collectively referred to as “threatened species.” According to the most recent report of the IUCN (2010a), among 7,000 plant species examined, 22% are under threat, and 33% could not be evaluated due to a lack of information. By way of contrast, less than 2% of about 4,000 vascular plant species in Korea are designated as endangered species. Such a large difference in the proportion of endangered species is not likely to reflect an actual difference in endangerment, but rather a difference in information sufficiency and endangerment criteria.

Several authors have argued against the definition and categorization of endangered species (e.g. Kim 1994, Bang and Ahn 2005, Chang et al. 2005). For example, when determining the level of endangerment of those 64 species according to the IUCN’s Red List, 33 are categorized as species of least concern, which have only a slim chance of extinction (Kim et al. 2001, Chang et al. 2005). Additionally, current lists of endangered species may not represent Korean plant species’ phylogenetic or evolutionary diversity. For example, certain groups of plants such as the Orchidaceae, Ranunculaceae, and Liliaceae appear to be overrepresented. On the other hand, gymnosperms and endemic species are underrepresented. Gymnosperms are in more danger of extinction than birds or mammals (IUCN 2010a). Approximately 70 gymnosperm species are present in Korea (Korea Forest Service 2010), and four of them--e.g.,

Most species in danger of extinction may consist of one or just a few populations, and their populations tend to be rather small in size. Therefore, population dynamics information is critical to evaluations of endangerment. Reproductive ecology is a key component affecting population parameters (Kang and Bawa 2003), but studies concerning the reproductive ecology of endangered species in Korea are relatively limited (Yu et al. 1976, Kang et al. 2000, So et al. 2008). Almost all endangered species, excluding a few such as

The IUCN (1993) urges that 10% of land in each country be set aside as conservation areas, because habitat loss and degradation are the principal factors responsible for the extinction of species of diverse taxa. However, excluding sea area, Korean conservation areas comprise only 4.9% of the land, and must be doubled to meet the IUCN’s 10% coverage target. Doubling the size of conservation areas is not easy: the acquisition of new land, particularly larger parcels, frequently involves great costs, both economically and socially. Then, for the limited conservation areas, methods to support the ecosystem functions, including high biodiversity, must be devised.

In this study, we determined that the number of endangered plant species increases in a linear fashion with the size of the national park. Only two endangered plant species are observed in the secondary conservation areas, i.e., provincial parks, ecosystem conservation areas, and wetland conservation areas, all of which are far smaller in area than the national parks. This may reflect the effect of small size. Similar area effects have also been reported for vascular plants, as well as introduced plants, butterflies, and birds in Korean western and southern sea islands (Choi 2000, Chung and Hong 2002, Rho 2010). Several small reserves may be particularly inappropriate for areas characterized by high biodiversity, highly endemic taxa, or certain taxa such as vertebrates (e.g., Rodrigues and Gaston 2001). However, several authors have argued that several small reserves, if selected carefully, can prove quite successful in meeting conservation needs (Primack 1993, Turner and Corlett 1996).

The Global Strategy for Plant Conservation (United Nations Environment Programme 2010) proposed a target for plant conservation, i.e.,

As suggested previously by Possingham et al. (2005), locating gap areas in which the density of endangered or key species is high but is not protected by law, and adding it as a new conservation area or conservation network component may prove a more feasible conservation option. The Global Strategy for Plant Conservation (United Nations Environment Programme 2010) suggests protecting 50% of the most important areas for plant diversity. Although we did not, in this study, quantify the percentage of gap areas in which endangered species are concentrated but not protected by law, Figs. 2 and 3 clearly demonstrate that the conservation areas do not fulfill the Global Strategy’s 50% land coverage goal. By way of contrast, five species (

In Fig. 5, the region between Odaesan National Park and Juwangsan National Park, mountain regions of Gangwon Province and Gyeongsangbuk Province, southwestern coast, and islands such as Gangwha, Jeju, and Ulleung appear to be important gaps in the conservation of endangered species. In order to maintain the endangered species in these areas, we must understand the areas’ historic landscapes and native vegetation. For example, Jeju and Ulleung’s particular landscape and vegetation are important resources in and of themselves, and these two islands, at a national level, are focal sites in species diversity. One-third of Korea’s endangered species reside on Jeju Island, but the majority of them inhabit the shore and/or lowland, which are not legally protected areas. Habitats in Jeju are undergoing fragmentation through road construction and tourist facility increases, resulting in the isolation and/or destruction of wild species habitats (Kang et al. 2008). Due to road construction, endemic species such as

In the face of rapid environmental changes such as human population increases, urbanization, and climate changes, converting the gap areas to endangered species’ habitats, or at least including them in the habitat networks, would help to enable the continued existence of endangered species. This should be quite possible because new conservation areas have continued to increase in Korea. Similar analyses can be conducted for endangered or key species of other taxa, such as birds or vertebrates. Upon the expansion or connection of conservation areas, gaps in common among key taxa should be afforded priority as new conservation areas.