To determine whether or not the female Korean salamander, Hynobius leechii, responds to water currents and, if so, whether those responses depend on their reproductive conditions, we evaluated the responses of ovulated and oviposited females to 1-Hz water currents generated by a model salamander with and without the placement of a transparent water current blocker between the model and the test females. The ovulated females responded to water currents by turning their heads toward, approaching, and/or making physical contact with the model. When the water current blocker was in place, the number of salamanders that approached the model was reduced significantly. The approaching and touching responses of ovulated females were greater than those of oviposited females, whereas the other measurements evidenced no differences. None of the responses of the oviposited females to water currents was affected by the presence of the blocker. Our results indicate that female H. leechii responds to water currents via a mechanosensory system.

In many animal taxa, the mechanosensory system performs a critical function in a variety of activities, including conspecific and individual recognition, alarm response, foraging, and reproduction (Vogel and Bleckmann 1997, Baker and Montgomery 1999, Hill 2001, Quirici and Costa 2007, McHenry et al. 2009). The functions of the mechanosensory system in reproduction have been assessed in different animal species, including rotifers (Joanidopoulos and Marwan 1999), spiders (Maklakov et al. 2003, Quirici and Costa 2007) and salmon (Satou et al. 1994a); such studies demonstrated that a healthy mechanosensory system is crucial for successful reproduction. Urodela species possess a well-developed mechanosensory system (Lannoo 1987, Lee and Park 2008b), the functions of which in foraging and predation have been relatively well-studied (Fritzsch and Neary 1998). However, the reproductive functions of this system have yet to be well-established.

Unlike the majority of other salamanders, salamanders in the Hynobiidae fertilize eggs externally (Salthe 1967). When a

Previous studies have demonstrated that when

In order to determine whether the female Korean salamander,

>

Animal collection and husbandry

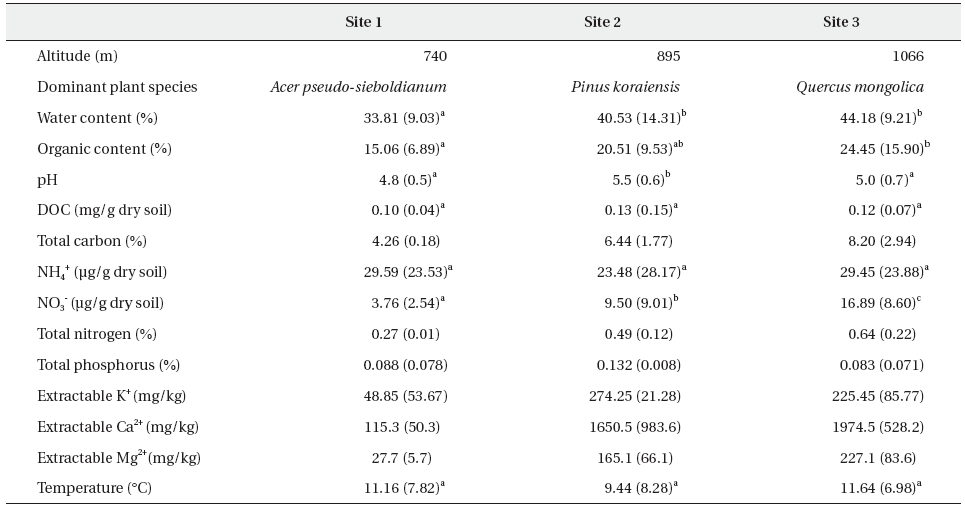

The salamanders employed in this study were collected from small ponds in the Research Forest of Kangwon National University (N 37o46'52.9'', E 127o48'55.4'') located at Donsan-myeon, Chuncheon-si, Kangwon, South Korea several times from early March to mid-April 2008. Females were determined on the basis of the presence of ovulated eggs in the slightly transparent abdominal cavity, and were individually maintained in small plastic boxes (13 cm long × 7.5 cm wide × 4.5 cm high) filled with aged tap water to a depth of 3 cm and provided with wet paper towels in which the animals could conceal themselves. The boxes were maintained in an environmental chamber, the air temperature of which ranged between 8-10℃. The humidity was approximately 70%, and the photoperiod was 12D:12L.

The responses of the females to water currents were measured under both ovulated and oviposited conditions. In each condition, females were tested randomly with and without a water current blocker placed between them and the model generating water currents to determine whether the females respond to water currents using their mechanosensory system. In a previous study (Park et al. 2008), the blockage of water currents allowed for the successful determination of whether or not the mechanosensory system plays a role in male salamanders' responses to water currents. We determined the order of the experiments (with and without the blocker) by flipping a coin, and the females had at least a 2-hour rest period between the two experiments. After the experiments on ovulated females (which were conducted between the 24 March and 28 March, 2008), all of the ovulated females were permitted to mate with males. After the completion of mating, between 29 March and 3 April, 2008, we tested the oviposited females in the same fashion as the ovulated females. All experiments were conducted between 1900 and 0200 under dim light, < 0.1 Lux (YL102; UINS, Seoul, Korea).

Because detailed information regarding the generation of water currents and the measurement of salamanders' responses to water currents has been published previously, along with diagrams (Park et al. 2008), we briefly describe our methods here. We placed sand at the bottom (∼5 cm deep) of an experimental tank (48 cm long × 27 cm wide × 30 cm high) and filled the tank with aged tap water to a depth of 5 cm above the sand. We placed a plastic model salamander similar to a real male salamander on a tree twig (∼1 cm in diameter) positioned such that it crossed the tank from one lower corner to the opposite upper corner. The lower body of the model salamander was submerged; the upper body remained out of the water. In this posture, the model salamander could generate water currents similar to the water currents generated by male body undulation during mating. The model was controlled by a transparent fishing line connected to a hand-made vibration generator. In the experiments, we employed 1-Hz water currents because this frequency had been successfully used in previous experiments with males (Park et al. 2008). Additionally, we placed a wire circle (15 cm in diameter) centered on the cloaca of the model salamander at 5 cm above the water surface in order to determine whether females approached the model and to measure the amount of time they remained within the circle.

Prior to beginning the experiments, each female was provided with a 5-minutes period to acclimate to the experimental tank without any water vibration. The female was then exposed for 5 minutes to 1-Hz water currents while its responses were recorded with a low-light video camera (10IR LED, SLCC). After each experiment, the tank walls and sands were rinsed thoroughly using tap water to avoid any possible olfactory interference. In the analysis, we counted the number of times the female's head was oriented toward the model, the number of times it approached and/or touched the model, and the amount of time it remained within the 15-cm circle. Head orientation was considered to be achieved when the female turned its head toward the model at an angle of greater than 45 degrees from the body trunk axis. Approach to the model was achieved when the female's snout entered the 15-cm circle. The time of stay was the amount of time from the moment the female's snout entered the circle to the moment it exited the circle. If the female's snout was within the circle when the initial current was generated, we measured the time of stay from the beginning of the experiment. Touching of the model was recorded whenever the female's snout made physical contact with any part of the model.

The water current blocker (13 cm long × 6 cm wide × 5 cm high, thickness 1.5 mm) was constructed of transparent acrylic plates and completely surrounded the model salamander at a distance of approximately 2-3 cm. The blocker allowed the model to undulate, but did not allow water currents to spread. In experiments conducted with a blocker, we measured only the number of head orientations and approaches toward the model. Due to the presence of the blocker, female salamanders could not remain within the circle or touch the model.

We compared the responses of the two groups of salamanders - those that had ovulated and those that had oviposited - to the water currents by a model salamander with and without the transparent current blocker. We employed a chi-square test to compare the number of responding individuals, and used a Wilcoxon's signed-rank test to compare the number of responses and the time of stay within the circle between the groups. All data were expressed as means ± SE.

The responses of 22 ovulated (2.09 ± 0.06 days before oviposition) and oviposited (3.09 ± 0.06 days after oviposition) females (snout-vent length, 6.26 ± 0.09 cm; body weight, 5.15 ± 0.21 g) to 1-Hz water currents were measured. Among the 22 ovulated females tested, 12 performed head orientation and approached the vibration model, and 11 touched the model (Fig. 1). However, only 3 females approached the model when the water currents were blocked (chi-square test,

Ovulated females executed 0.82 ± 0.19 head orientations, 0.68 ± 0.15 approaches, and 0.68 ± 0.18 touches over the 5-minutes test period (Fig. 1). With the water current blocker, the number of approaches was reduced significantly (0.27 ± 0.16,

In our experiments, the ovulated females performed head orientations and approached the vibration model; they also touched the model. Approximately 53% of ovulated females responded to water currents, similar to the previous observation that 56% of male

In particular, the model-touching response of ovulated females to water currents was more profound than that of the oviposited females. Unlike the ovulated females, only approximately 14% of oviposited females responded to water currents. Also, the placement of a water current blocker did not affect any of the responses of the oviposited females. These results indicate that the reproductive condition of females influences their responses to water currents. Similar results have been reported in previous studies. For example, the responses of ovulated

Why do females respond to water currents? Two possible explanations have been proposed for this phenomenon. The first is that ovulated females may simply wish to confirm the presence of males who would fertilize their eggs. In our experiments, ovulated females laid their eggs an average of 1.23 days after the experiments, meaning that females did not approach the model salamander because they were close to oviposition. In a previous study, females approached body-undulating males throughout the mating period, although the frequency of approaches increased gradually, beginning approximately one hour prior to oviposition (Kim et al. 2009). In the field, unfertilized eggs were frequently detected in the early breeding season (personal observation), probably because females were unable to find appropriate males to fertilize their eggs, or vice versa. In order to prevent the failure of egg fertilization, early confirmation of the presence of males at a site that could be readily approached by females may prove important.

The second explanation is that female

The mechanosensory system performs a crucial function in the reproduction of many different species (Satou et al. 1994b, Joanidopoulos and Marwan 1999, Quirici and Costa 2007), but relatively little is currently known regarding urodeles. The results of our previous (Park et al. 2008, Kim et al. 2009) and current studies indicate that the water currents generated by a male's body undulation might be employed for male-male competition and male-female interactions. Considering that pheromones from female