The red algal genus Grateloupia is the most speciose within the Halymeniaceae with about 96 species (Guiry and Guiry 2009) that are widely reported from the tropical to warm temperate regions of the world. The genus is characterized by compressed to foliose, linear to lanceolate, rarely unbranched, usually branched proliferously thalli, having superficial spermatangia in nemathecial sori, 2-celled carpogonia, and cruciate tetrasporangia in cortical layer (Kawaguchi et al. 2004). Grateloupia is a recent focus of research because several species of the genus are likely introduced from their native origins, e.g., Korea and Japan, to different biogeographic regions, e.g., Europe, New Zealand, and north America (Gavio and Fredericq 2002; Verlaque et al. 2005; Garcia-Jimenez et al. 2008; Miller et al. 2009).

Previous investigations primarily based on comparative sequences of the chloroplast-encoded large subunit of the RuBisCO gene (rbcL) have shown that other genera of the Halymeniaceae, characterized by identical ampullary structures, fall within a large Grateloupia clade, supporting the generic concept by Chiang (1970) arguing that the nature of the auxiliary cell ampullae holds the key towards a natural classification of the Halymeniaceae (De Clerck et al. 2005a). Consequently, Prionitis and Phyllymenia, both characterized by Grateloupia-type auxiliary cell ampullae, have been merged into Grateloupia (Wang et al. 2001; De Clerck et al. 2005b). Apart from elucidating taxonomic status of some morphologically similar species and refining generic delineations, most previous studies indicated the presence of extensive cryptic diversity in the genus (De Clerck et al. 2005a).

In a monographic study on the Halymeniaceae, Lee (1987) gave morphological and anatomical details of 13 species of Grateloupia and Pachymeniopsis (now a synonym of Grateloupia) in Korea. In addition, Lee and Lee (1993) studies detailed morphology of Grateloupia (as Pachymeniopsis). These species are listed in the catalogue of Korean algae (Lee and Kang 2001): G. acuminata Holmes, G. asiatica Kawaguchi et Wang (as G. filicina [Lamouroux] C. Agardh), G. crassa Yamada et Segawa, G. divaricata Okamura, G. elliptica Holmes, G. imbricata Holmes, G. imbricata Holmes f. flabellata Okamura, G. lanceolata (Okamura) Kawaguchi, G. livida (Harvey) Yamada, G. prolongata J. Agardh, G. ramosissima Okamura, G. sparsa (Okamura) Chiang, and G. turuturu Yamada. Recently, Lee (2008) reported G. angusta (Okamura) Kawaguchi et Wang, G. chiangii Kawaguchi et Wang, G. crispata (Okamura) Lee, G. crispata (Okamura) Kawaguchi et Wang, G. kurogii Kawaguchi, and G. subpectinata Holmes from Jeju. However, despite 19 species listed in Korea and their presumed ecological and economic importance, there are no molecular taxonomic studies of the genus in Korea.

The objective of the present study is to survey and reexamine the various records of the species of Grateloupia in Korea, in an attempt to produce a useful taxonomic guide to future studies on the Korean Grateloupia. During the course of the study, we determined rbcL haplotypes of the Grateloupia species in Korea and confirmed the occurrence of eight species from among the 19 species in the catalogue of Korean marine algae (Lee and Kang 2001). We also reconstructed phylogenetic trees of 77 rbcL sequences from Grateloupia including 42 previously published sequences and compared sequences divergence within each species analyzed.

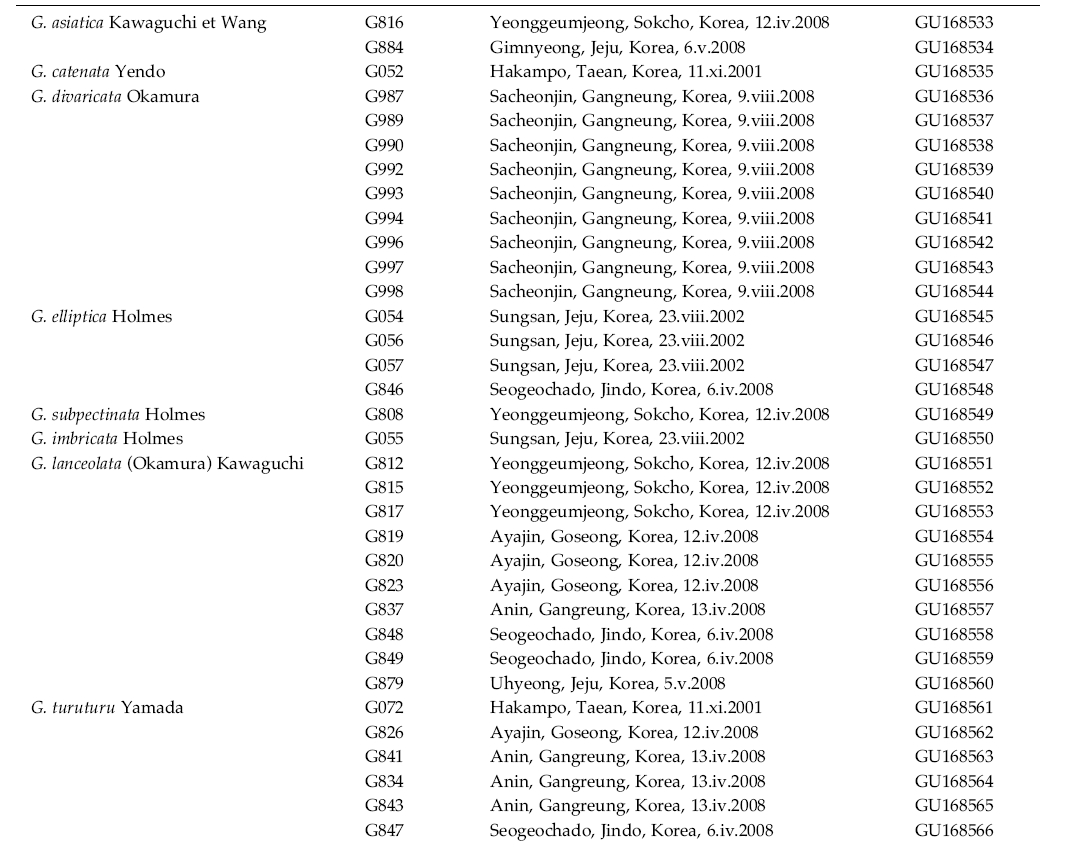

Description of habitat, location and date of collection for 34 specimens used in this study can be found in Table 1. Voucher specimens are deposited in the Chungnam National University Herbarium, Daejeon, Korea.

Genomic DNA was extracted from approximately 5 mg of dried thalli ground in liquid nitrogen with Plant Mini Kit (Invitek, Berlin-Buch, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The plastid rbcL region was amplified using primers F7-R753 and F645-RrbcS start and sequenced using primers F7, F645, R753, and RrbcS start (Freshwater and Rueness 1994; Lin et al. 2001; Gavio and Fredericq 2002). PCR amplification was performed from a total volume of 25 μL, containing 0.5 U TaKaRa Ex TaqTM DNA polymerase (TaKaRa Shuzo Co., Tokyo, Japan), 2.5 mM of each dNTP, 2.5 μL of the 10X Ex TaqTM Buffer (Mg2+ free), 2 mM MgCl2, 10 pmol of each primer and 1-10 ng template DNA. PCR reaction was carried out with an initial denaturation at 94°C for 10 min, followed by 35 cycles of amplification (denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 50°C for 30 s and extension at 72°C for 2 min) with a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. PCR products were purified with High Pure PCR Product Purification Kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) before direct sequencing. The sequences of the forward and reverse strands were determined for all taxa using an ABI PRISMTM 377 DNA Sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) at the Research Center, Chungnam National University, Daejon, Korea. The electropherogram output for each specimen was edited using the program Sequence Navigator® v. 1.0.1 (Applied Biosystems). The alignment was based on the alignment of the inferred amino acid sequence, and this was refined visually.

We used Kimura’s two-parameter model to calculate the pairwise distances between the rbcL sequences and identified the same sequences as identical haplotypes.

Maximum likelihood (ML) analyses were performed using PAUP* with best-fitting evolution model. The model of sequence evolution was chosen based on results from the successive approximation method (Sullivan et al. 2005). Tree likelihoods were estimated using a heuristic search with 100 random-additionsequence replicates, and tree bisection-reconnection (TBR) branch swapping. To test the stability of nodes, ML bootstrap analyses were performed with 500 replicates.

Maximum parsimony (MP) trees were constructed for each data set with PAUP* 4.0b.10 software (Swofford 2002) using a heuristic search algorithm with the following settings: 1,000 random sequence additions, TBR branch swapping, MulTrees, all characters unordered and unweighted, and branches with a maximum length of zero collapsed to yield polytomies. Bootstrap values for the resulting nodes were assessed using 1,000 bootstrapping replicates with 10 random sequence additions.

Bayesian analyses were conducted with MrBayes ver.3.1 software (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck 2003) using the Metropolis-coupled Markov chain Monte Carlo method with the GTR + <>; + I model for individual data sets. Six million generations in two independent runs were performed with four chains. Trees generated were sampled every hundredth generation. The 8,690 burn-in period was identified graphically by tracking likelihoods at each generation to determine whether the likelihood values had reached a plateau. The 102,622 trees sampled at stationarity were used to infer Bayesian posterior probability.

A total of 1,257 base pairs (bp) rbcL were aligned for 68 taxa including 34 previously published sequences.Variable sites occurred at 87 positions (6.9%), and 326 positions (25.9%) were parsimoniously informative. MP analysis of the data resulted in seven optimal trees of 1,274 steps with 0.426 consistency index, 0.793 retention index, and 0.338 rescaled consistency index. In ML analysis, the -ln likelihood score was estimated at 8005.214686 under the GTR + <>; + I model.

This is the first report documenting molecular taxonomy of the genus Grateloupia in Korea. Our rbcL tree (Fig. 1) reveals that Grateloupia formed a monophyletic clade with a strong support (95% for ML, 91% for MP, and 1.0 for BA), as seen in previous studies (Kawaguchi et al. 2001; De Clerk et al. 2005a, b). Within the genus, eight species are clearly separated: G. asiatica, G. catenata, G. divaricata, G. elliptica, G. imbricata, G. lanceolata, G. subpectinata, and G. turuturu. Most of the species confirmed here have been reported in Korea (Lee and Lee 1993; Lee and Kang 2001; Lee 2008). Grateloupia asiatica, which was previously known as G. filicina in Korea (Lee and Kang 2001), is confirmed to occur in Jeju and Sokcho. It has been introduced from the northwest Pacific to France (Verlaque et al. 2005).

Our rbcL data confirm the occurrence of G. catenata in Hakampo on the west coast of Korea, which was reinstated by Wang et al. (2000) on the basis of morphology and rbcL sequences. The species was known as G. porracea in the floristic studies by Lee et al. (1997, 2000) and later it was listed as a synonym of G. filicina (Lee and Kang 2001). Since the collection site of G. catenata in the present study is very close to Padori, where Lee et al. (1997, 2000) studied, our data confirmed their identification.

Grateloupia divaricata occurs in Korea and Japan (Lee 1987; Yoshida 1998). The difference between G. divaricata specimens from Korea and Japan (AY178764, AB038609) was 1-4 bp (0.1-0.3%, p-distance). Since the species occurs in Southeast Asian waters including Korea and Japan (Silva et al. 1987), analysis of additional samples covering its distribution range will give a better understanding of the genetic variation of the species.

Grateloupia elliptica is distributed in Korea and Japan (Lee 1987; Yoshida 1998). It is unexpected that Korean specimens differed by 30 bp (2.4%) from those in Japan (AB055476, AB038605). However, since all the samples produced a monophyletic clade strongly supported by ML and MP bootstrap values and posterior probability, we tentatively refer to it as G. elliptica. Additional sampling is required to further address the genetic difference.

Grateloupia imbricata occurs on the southern coast of Korea (Lee 1987). Its occurrence in Jeju is demonstrated in the present study as in our previous study (Garcia- Jimenez et al. 2008). Although it is native to Korea and Japan, G. imbricata has recently been introduced to the Canary Islands. However, the population size of the species is small in a few locations in the Canary island (Garcia-Jimenez et al. 2008).

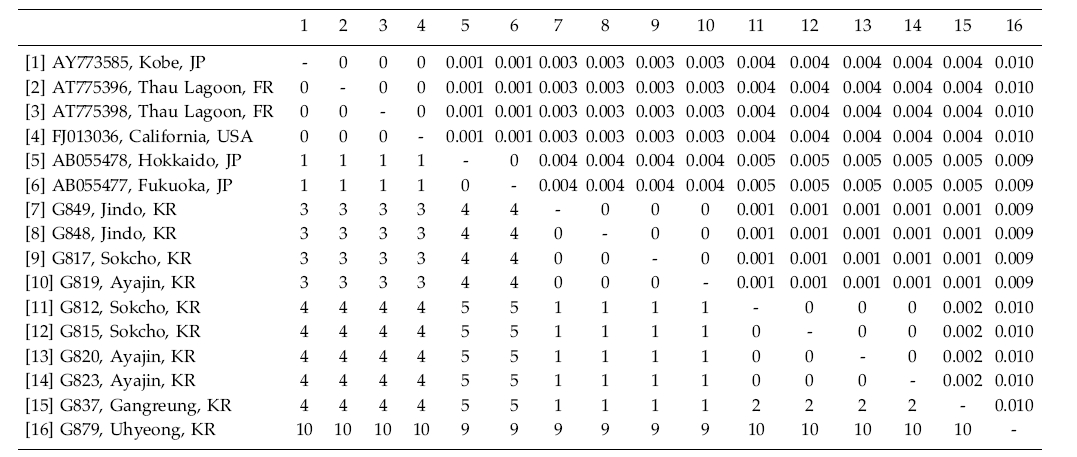

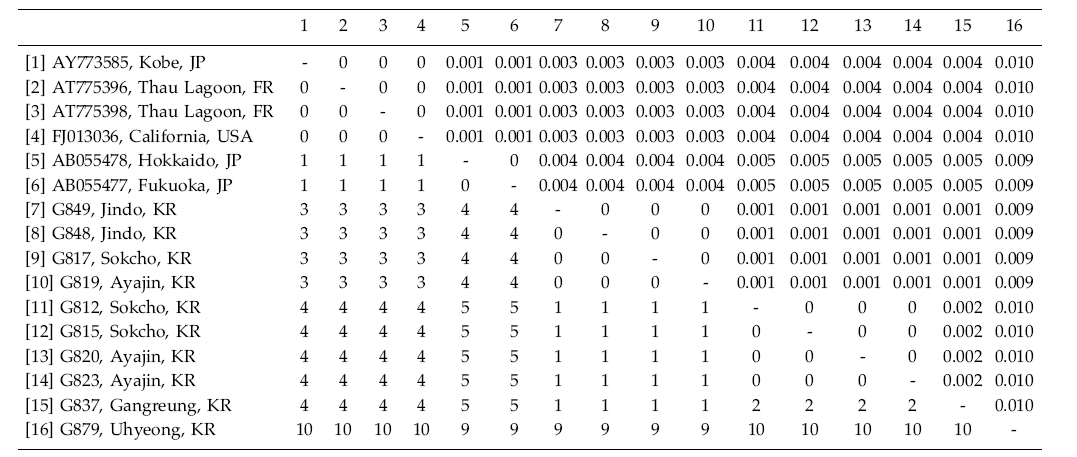

Grateloupia lanceolata has been reported as introduced from Japan to the Mediterranean Sea (Verlaque 2001; Verlaque et al. 2005). Korean specimens differed by about 4 bp (ca. 0.4%) from samples obtained in Japan and the USA (Table 2). Interestingly, specimens in Jeju differed by 10 bp (1% divergence) from those in other places in Korea. However, because all the specimens formed a monophyletic clade and the morphology is similar to G. lanceolata, we tentatively included the specimens under the name of G. lanceolata. Additional sampling with an analysis of the cox1 gene is on-going to uncover cryptic diversity within the species.

Although it was until recently regarded as Grateloupia filicina, G. subpectinata is distinguished by its fleshy texture and wider and thicker axes, longer marginal and surface proliferations and much elongated, oblong auxiliary cells. It is also different from G. filicina in rbcL sequence (Faye et al. 2004). Our study identified G. subpectinata in Sokcho and Jeju, confirming its occurrence in Jeju (Lee 2008). However, our sample differed by 7 bp from the sample obtained in Wakayama prefecture, Japan (Faye et al. 2004). G. subpectinata has been introduced from Japan to France (Verlaque et al. 2005).

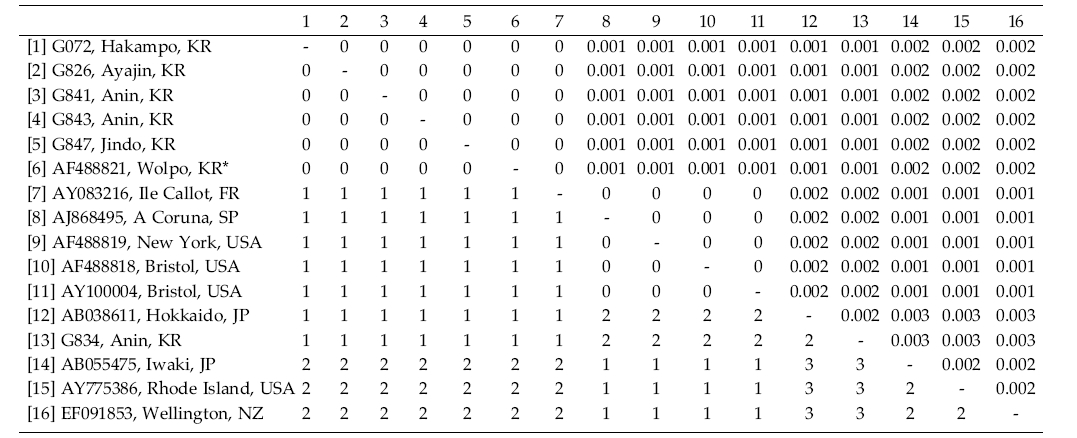

Grateloupia turuturu specimens from Hakampo on the west coast, Jindo on the south-western coast, Anin, Ayajin and Wolpo on the east coast of Korea had identical haplotypes with those from Thau Lagoon and Brittany, France and Hampshire, UK (Table 3). However, some specimens from Korea differed by 1-3 bp (0.1-0.3%) from those collected from France (AY775399, AJ868493, AY100002, AY100003), New Zealand (EF091853), Spain (AJ868495), UK (AJ868493), and USA (AF488819, AF488818, AY775386). It is a well-known species due to its recent introduction from its native habitat in the northwest Pacific Ocean region to Atlantic and Australasian waters (e.g., Gavio and Fredericq 2002; Verlaque et al. 2005; Saunders and Withall 2006).

Recent progress in molecular tool contributed much to the identification of invasive marine algae (Booth et al. 2007). Grateloupia is a major invasive genus because six species have been introduced from Far East Asian waters to Europe and North America: G. asiatica, G. imbricata, G. lanceolata, G. patens, G. subpectinata, and G. turuturu (Gavio and Fredericq 2002; Verlaque et al. 2005; Garcia- Jimenez et al. 2008; Miller et al. 2009). Verlaque et al. (2005) stated that the species were introduced from Japan and (or) Korea to Thau Lagoon, France during the years 1971-1976 when there were massive importations of Japanese oysters. According to Milller et al. (2009), G. lanceolata was introduced with the cultivation of Asian oysters in California and Puget Sound, Washington beginning from 1909 to the middle 1970s.

Grateloupia lanceolata and G. turuturu showed low variation of their rbcL sequences between samples from the native (Korea and Japan) and the introduced areas (New Zealand, France, UK, and USA), implying a short and recent history of the settlement in the newly adapted areas. Although the number of the samples of the species analyzed was uneven, G. lanceolata was the most variable in rbcL sequences. There were no identical haplotypes in G. lanceolata between Korea and France/USA, despite the analysis of several samples collected along the entire coast of Korea. However, an identical haplotype of the species was found between Kobe (AY775385), Japan and California (FJ013036), USA (Table 2). Further taxon sampling will show if the introduced haplotypes of G. lanceolata in Europe and North America is really absent or rare in Korea. In contrast, the introduced haplotype of G. turuturu in France and UK commonly occurs in Korea (Table 3). It is interesting to study why haplotype sharing is rare in G. lanceolata while it is common in G. turuturu. In addition, analysis of rapidly evolving genes such as nuclear ITS or mitochondrial cox1 gene will show the genetic source of the introduced populations. Since biological invasions present interesting evolutionary issues, the genetic variation and genomic rearrangements of invasive species will give a new highlight on the introduced pathway and the fate of the invasive populations (Lee 2002; Strayer et al. 2006; Booth et al. 2007).

In conclusion, we confirmed the occurrence of eight species of Grateloupia in Korea using rbcL sequences which reinforces the taxonomic discrimination of the species and their putative relatives. The molecular taxonomic work is on-going in our laboratory to identify the remaining 11 species of the genus. As for G. elliptica and G. lanceolata showing some divergent specimens, new molecular markers such as mitochondrial cox1 region will show whether the divergent specimens represent congeneric species or some variable populations. Our preliminary research will be rewarding in contributing towards a correct inventory of Korean red algae which are used as biotechnological resources in the future.

![Maximum likelihood (ML) tree of Grateloupia in Korea using rbcL sequences in the GTR + Γ + I evolution model (-lnL = 8005.214686; substitution rate matrix RAC = 0.188084, RAG = 0.770560, RAT = 0.834467, RCG = 0.612457, RCT = 10.055827, RGT = 1; base frequencies πA = 0.30735, πC = 0.16597, πG = 0.21885, πT = 0.30784; shape parameter [α] = 0.188084). Values above each clade refer to ML and Maximum parsimony (MP) bootstrap values and Bayesian posterior probabilities.](http://oak.go.kr/repository/journal/10226/JORHBK_2009_v24n4_231_f001.jpg)