The centric diatom Stephanodiscus Ehrenberg 1846 is commonly present in freshwater environments, and several species are important bio-indicators of water quality, particularly for eutrophicated waters (Ha et al. 2002). Conventionally, their taxonomic identities are determined by microscopic observations of certain morphological characters, such as the pattern of the central area of the exoskeleton, and density and branching of the striae (Oliva et al. 2008). However, morphological discrimination of these species is very difficult, because of small size (less than 15 μm) and a number of recorded different Stephanodiscus species (approximately 124 taxa) according to Guiry and Guiry (2009). In addition, morphologies of Stephanodiscus are similar to those of other freshwater centric diatoms, e.g. Cyclotella and Discostella (formerly, these represented the stelligeroid group of Cyclotella [Houk and Klee 2004]). Moreover, several centric diatoms of different species sometimes are co-occurring. Many uncertainties about the proper identities of the centric diatoms are, therefore, remaining.

Recently, DNA-based taxonomy is widely used for the discrimination of small-size organisms, including diatoms and dinoflagellates (Karsten et al. 2005; Ki et al. 2009). Indeed, molecular analyses (e.g. immunoassays, PCR assay, DNAchip), including phylogenetic inferences, are very effective to discriminate morphologically similar, microscopic-size organisms. In most cases, these molecular approaches are based on the DNA sequences of the nuclear ribosomal DNA (rDNA), because it occurs in all living organisms, and many rDNA sequences are available, compared to other genes (e.g. actin, α-, β?-tubulin, and Hsp90). The rDNA sequences have been used for the discrimination of centric diatoms and for the phylogenetic analyses (Alverson et al. 2007; Kaczmarska et al. 2007). Most studies on the freshwater centric diatoms have been biased to Cyclotella, particularly for the ystematics and phylogenetic relationships of cyclotelloid diatoms (Beszteri et al. 2005, 2007; Alverson et al. 2007). More recently, genetic divergence between Cyclotella and Discostella has been studied, by comparisons of a wide range of rDNA sequences (Jung et al. 2009). With regard to molecular analyses of Stephanodiscus, Kaczmarska et al. (2005) showed for the first time that Cyclotella and Stephanodiscus were not belonging to the same phylogenetic clade, making the family Stephanodiscaceae paraphyletic. Recently, Alverson et al. (2007) reported phylogenetic relationships of thalassiosiroid diatoms, representing the separations of the freshwater centric diatoms, e.g. Cyclotella, Discostella and Stephanodiscus. Recently, the author reported high molecular genetic divergences between Cyclotella and Discostella, suggesting that rDNA may be a suitable molecular marker for the discrimination of the two genera and species (Jung et al. 2009). Excluding these works, little attention has been paid on the molecular analyses of Stephanodiscus.

In the present study, the author sequenced nuclear rDNA, spanning the 18S to the 28S rDNA, of S. hantzschii and Stephanodiscus sp., including a Korean isolate, and characterized molecular features of various rDNA regions according to each rDNA. Comparative analyses of individual 18S, 28S rDNAs were performed with some rDNAs of selected Stephanodiscus to reveal the rDNA relationships of the freshwater centric diatoms. In addition, molecular divergences between Stephanodiscus with other centric diatoms Cyclotella and Discostella were compared to evaluate their usefulness for the discrimination of freshwater centric diatoms. The studied S. hantzschii is one of the planktonic, cosmopolitan species and the Stephanodiscus blooms were recorded annually in Korean waters, particularly in the Paldang Reservoir and Nakdong River (Kim 1998; Ha et al. 2002; Han et al. 2002; Kim et al. 2008).

Water samples were collected from Paldang Reservoir (a reservoir in Han River) of Korea, when Stephanodiscus blooms occurred. The author isolated single cells of Stephanodiscus from field samples using the capillary method (Ki and Han 2005), and established a clonal culture (KHR001) of Stephanodiscus. An additional strain (UTCC 267) of S. hantzschii was commercially obtained from the University of Toronto Culture Collection of Algae and Cyanobacteria (UTCC). All the cultures were routinely maintained in Diatom Medium, DM, (Beakes et al. 1988), and were grown at 15℃, 12:12 h light:dark cycle, with a photon flux density of about 65 μmol photons m?2 s?1.

A total of 50 ml clonal cultures were harvested by centrifugation centrifugation at 8,000 rpm for 15 min. The concentrated cells were transferred to 1.5 ml micro tubes, 100 μl of TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0 and 1 mM EDTA) was added and the tubes were stored at ?20℃ until DNA extraction. Genomic DNA was isolated from the stored cells using the DNeasy Plant mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA).

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was subject to amplifythe 18S-28S rDNA of Stephanodiscus genomic DNA. Inthis case, the author used a set of PCR primers that targetedto bind nuclear 18S rDNA (a forward AT18F01, 5’-ACC TGG TTG ATC CTG CCA GTA G-3’) and 28SrDNA (a reverse PM28-R1318, 5’-TCG GCA GGT GAGTTG TTA CAC AC-3’), which are specific for diatoms(Jung et al. 2009). PCR was performed with 50 μl reactionmixtures containing 30.5 μl sterile distilled water, 5 μl 10x LA PCR buffer II (TaKaRa, Kyoto, Japan), 8 μl dNTPmix (4 mM), 5 μl of each primer (5 M), 0.5 μl LA Taqpolymerase (2.5 U), and 1 μl of template. PCR cyclingwas performed in a Bio-Rad iCycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules,CA) with 94°C for 2 min, following 35 cycles of 94°C for20 sec, 55°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 2 min, and a finalextension at 72°C for 10 min. Resulting PCR productswere electrophoresed in a 1.0% agarose gel (Promega,Madison, WI), stained with ethidium bromide, and visualizedby ultraviolet transillumination.

For DNA sequencing, desired PCR products were purified with a QIAquick PCR purification Kit (Qiagen GmbH, Germany). DNA sequencing reactions were performed in a ABI PRISM® BigDyeTM? Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit (PE Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using the PCR products (2 μl) as the template and 10 picomoles of the above PCR and internal walking primers. Labeled DNA fragments were analyzed on an automated DNA sequencer (Model 3700, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

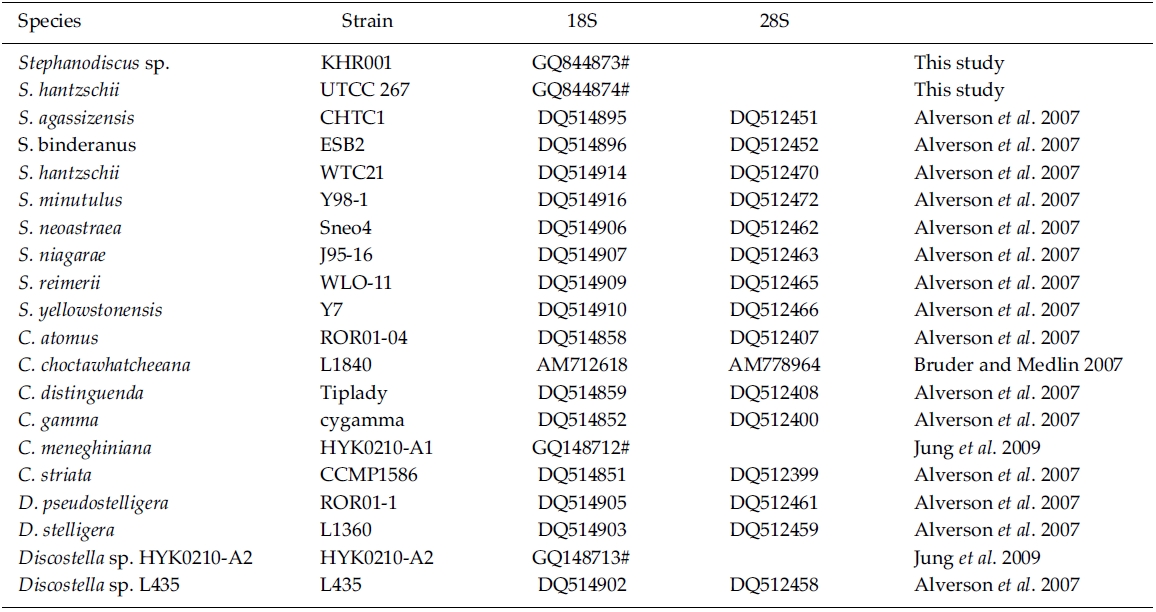

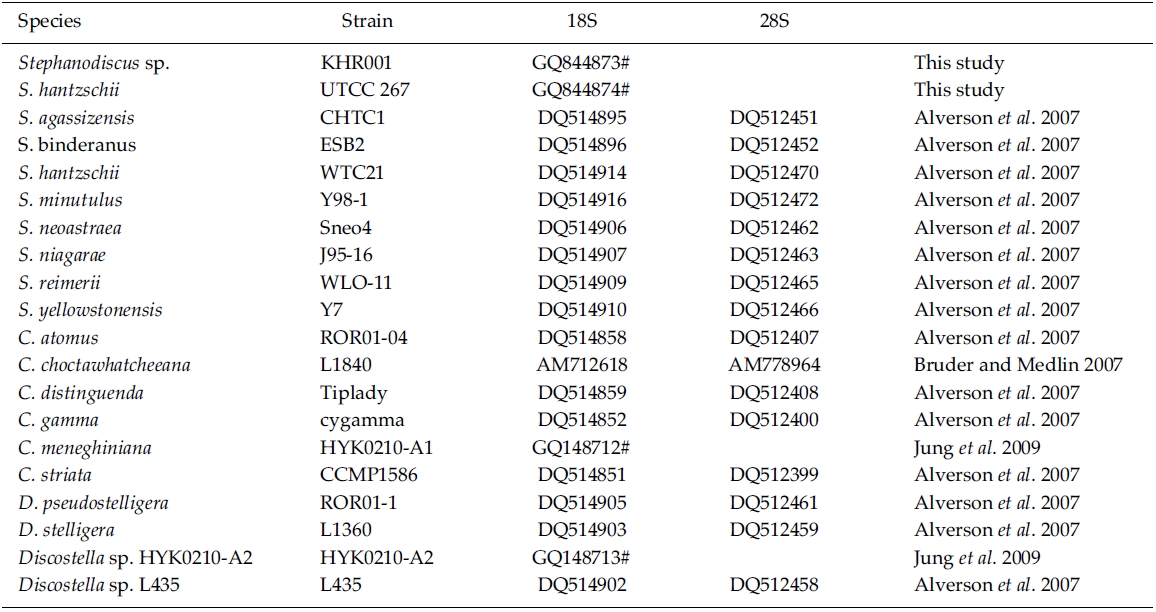

Editing and contig assembly of DNA sequences were performed using Sequencher 4.1.4 (Gene Codes, Ann Arbor, MI). The coding rDNAs were identified by comparison with those of other diatoms, including Cyclotella meneghiniana (GenBank No. GQ148712) and Discostella sp. (GQ148713). DNA sequences determined here have been deposited to GenBank as accession numbers GQ844873 and GQ844874.

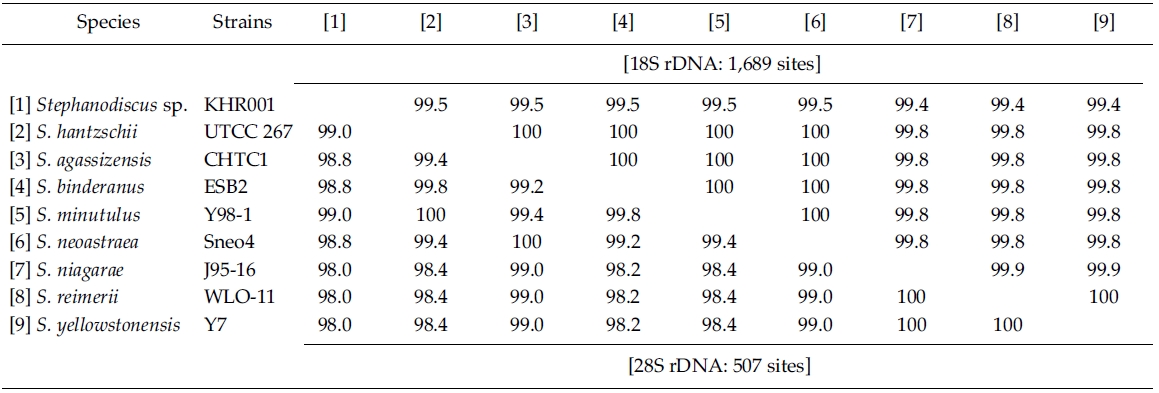

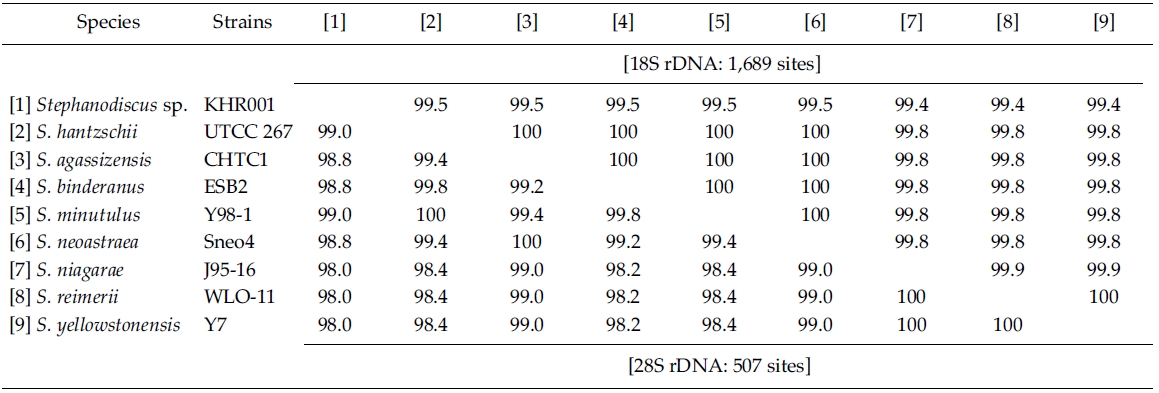

BLAST (The Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) searches were performed with the present rDNA sequence data and the available DNA sequences in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database. In addition, DNA sequences of S. hantzschii and a Korean Stephanodiscus were compared with those of other Stephanodiscus (see Table 1). DNA similarity scores of individual rDNA molecules were calculated by using pairwise sequences among nine selected species of Stephanodiscus in BioEdit 5.0.6 (Hall 1999). In addition, dot-plot analysis was carried out using the MegAlign 5.01 (DNAstar Inc., Madison, WI). Molecular genetic divergences of the nine species were measured with the Kimura two-parameter model in MEGA 4.0 (Tamura et al. 2007). Statistical analyses on the nucleotide comparisons were performed using SPSS 10.0.7 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

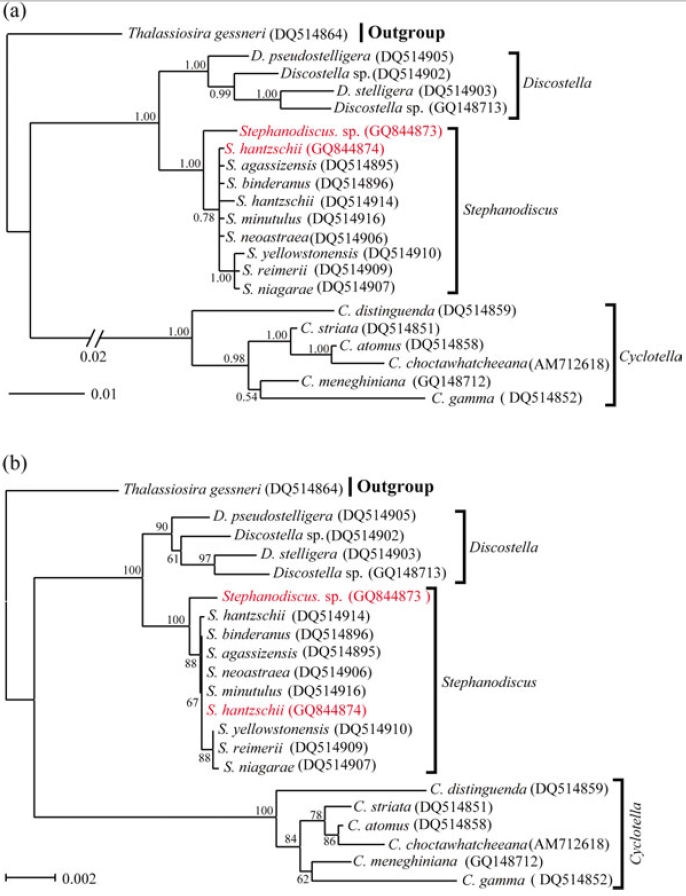

Phylogenetic analyses of the freshwater centric diatoms were carried out, following our previous work (Jung et al. 2009). In the present case, the author constructed two new data matrixes of individual 18S and 28S rDNAs, including ten Stephanodiscus, four selected Discostella, and six selected Cyclotella rDNAs (see Table 1). A total of 21 sequences, including the outgroup (Thalassiosira gessneri #AN02-08), were aligned with the Clustal W 1.8 (Thompson et al. 1997). The aligned sequences were trimmed each end to the same length. In addition, various regions and uncertain sequences were further corrected manually. Finally, only unambiguous positions of the aligned sequences were used in the subsequent analyses: 1,689 out of 1,813 alignment positions for 18S, 506 out of 1,264 for 28S). MrModeltest2 (Nylander 2004) was used to find the optimal model of DNA substitution for the Bayesian tree construction. As best-fit models for the present 18S rDNA dataset, the author selected the General Time Reversible plus Invariant sites plus Gamma distributed model (GTR+I+G) for 18S (-lnL = 3859.3) and for 28S (-lnL = 2260.4) from the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), respectively. A Bayesian tree of the 18S was implemented with the selected GTR+I+G substitution model in MrBayes 3.1.2 (Huelsenbeck and Ronquist 2001). The Markov chain Monte Carlo process was set to two chains (MCMC), and 1,000,000 generations were conducted. The sampling frequency was assigned as every 100 generations. After analysis, the first 2,000 trees were deleted as burn-in and a consensus tree was constructed. The phylogenetic tree was visualized with TreeView ver.1.6.6 (Page 1996). Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP) of more than 0.50 were indicated at each branch node. An additional Neighbor-Joining (NJ) tree was constructed with the same data matrix of 18S rDNA using the Maximum Composite Likelihood model in MEGA 4.0 (Tamura et al. 2007). For the 28S rDNA tree, Bayesian and NJ analyses were performed the same way as in the 18S analysis.

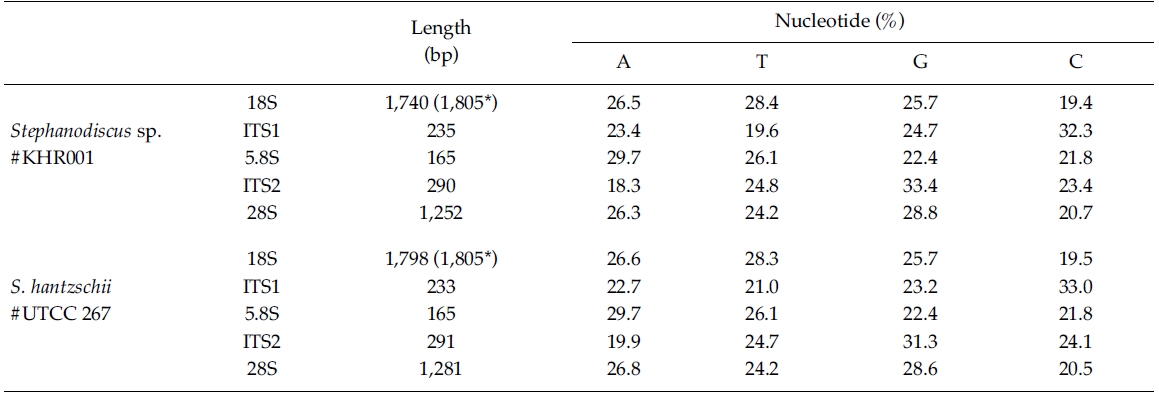

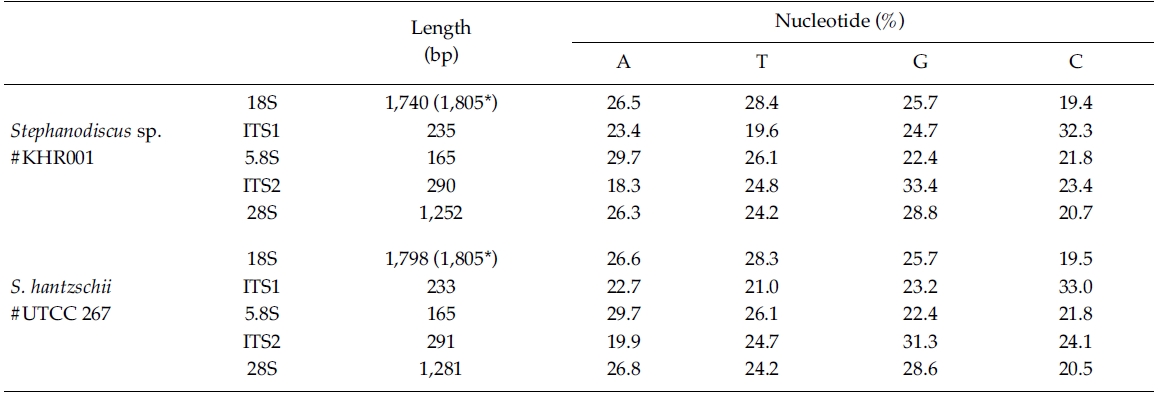

In the present study, DNA sequences of nuclearrDNAs, spanning the 18S to the D5 domain of the 28SrDNA, were determined from S. hantzschii #UTCC 267(3,768 bp; 47.9% GC) and a Korean Stephanodiscus sp.#KHR001 (3,682 bp; 48.3% GC), as shown in Table 2.Their gene structures were organized in the typicaleukaryotic fashion of rDNA (i.e. 18S-ITS1-5.8S-ITS2-28S).In general, the 28S rDNA, the largest rDNA codingregion, contains twelve hyper-variable domains(Hassouna et al. 1984; Lenaers et al. 1989), often designatedas divergent (D) domains. Of them, the presentsequences included D1 to D5 of the 28S rDNA. Uponcomparisons, most sequences available in public databases(e.g. DDBJ, EMBL, NCBI) were revealed fromD1/D2 domains of the 28S rDNA, while the others containmuch genetic information (Ki and Han 2007). Thepresent data included wider range of the 28S rDNA fromthe genus Stephanodiscus. With these data, the authorevaluated their molecular characteristics and compared 2representatives of Stephanodiscus with freshwater centricdiatom data available in the NCBI. Particularly, completelengths of the 18S rDNA sequences of S. hantzschii#UTCC 267 and Stepahnodiscus sp. #KHR001 were estimatedto be 1,805 bp, after incorporating undeterminednucleotides of the 18S rDNA 5’end into the present 18Ssequences, taking into account of available data (e.g.AM712618, DQ093370) recorded in GenBank (e.g.AM712618, DQ093370). These were nearly identical tothose of other relatives, including Cyclotella andDiscostella (Jung et al. 2009).

By database searches, the author found many partial 18S, 28S rDNA sequences revealed from Stephanodiscus, particularly by the work of Alverson et al. (2007). The rDNA ITS regions were only revealed from a few species, including S. hantzschii (U03078), S. niagarae (U03074-6, AF455267-9), and S. yellowstonensis (U03077). By using the ITS data, Wolf et al. (2002) demonstrated the same species of S. neoastraea and S. heterostylus. All the DNA sequence data (e.g. 18S, ITS, 28S) available in databases have been partially sequenced at a given locus. Here the author compared the present data with available partial sequences reported from Stephanodiscus (Tables 3, 4). Firstly, these sequences were compared with those of the NCBI database using the BLAST search algorithm. BLAST searches of individual rDNA sequences showed that a Korean Stephanodiscus sp. #KHR001 was highest matched with S. hantzschii #CCAP 1079/4 (GenBank DQ093370) with 99.5% similarity by 18S rDNA comparison, and was also matched to S. hantzschii #AT-N2 (AJ878502) with 98.5% similarity by 28S comparison. On the other hand, the ITS rDNA comparison showed that the top hit was recorded with S. niagarae (U03076) of 89.9% DNA similarity. BLAST searches of individual rDNA of S. hantzschii #UTCC 267 were similar to those of Korean Stephanodiscus spp. In the latter, the rDNA ITS was highly matched at 94.1% similarity with S. yellowstonensis (U03077) and at 96.9% similarity with S. hantzschii (U03078), respectively. Overall similari-ties of the coding rDNAs, e.g. 18S and 28S, were high within the genus Stephanodiscus.

Molecular comparisons showed that a Korean isolate of Stephanodiscus had a different genotype compared with other Stephanodiscus (Table 3), including S. hantzschii. The present Korean isolate was presumably identified as S. hantzschii based on routine morphological observations and previous studies (Han et al. 2002). As noted previously, morphological characteristics of Stephanodiscus are similar to each other, and a number of species (at least 124 species) have been described so far. n the present study, the author tentatively discriminated Stephanodiscus sp. #KHR001 (or named as Stephanodiscus sp. cf. S. hantzschii). Considering these molecular and morphological characteristics of Stephanodiscus, the author selected nine species of Stephanodiscus, including Korean one, and measured DNA similarities of both 18S and partial 28S rDNA sequences (Table 3). High DNA similarities were recorded among rDNA pairs of nine Stephanodiscus (>;99.4% in 18S rDNA, >;98.0% in 28S rDNA). Strikingly, DNA similarities of 18S rDNAs were considerably similar to one another. The present Korean isolate (KHR001) showed more than 99.5% similarity with S. agassizensis, S. binderanus, S. hantzschii and S. minutulus, respectively. By 28S comparisons, DNA similarities were highly recorded among the Stephanodiscus, while these data included the most variable domain D1/D2 within the 28S rDNA (Ki and Han 2007). These suggest that molecular genetic divergences within the Stephanodiscus are considerably low with approximately 1% in 18S rDNA and 2% in 28S rDNA, respectively. However, we detected high genetic divergences of other freshwater centric diatoms, e.g. Cyclotella and Discostella (Jung et al. 2009). Genetic divergences of freshwater centric diatoms may, therefore, be taxon-dependent rather than general molecular characteristics in the three diatom groups.

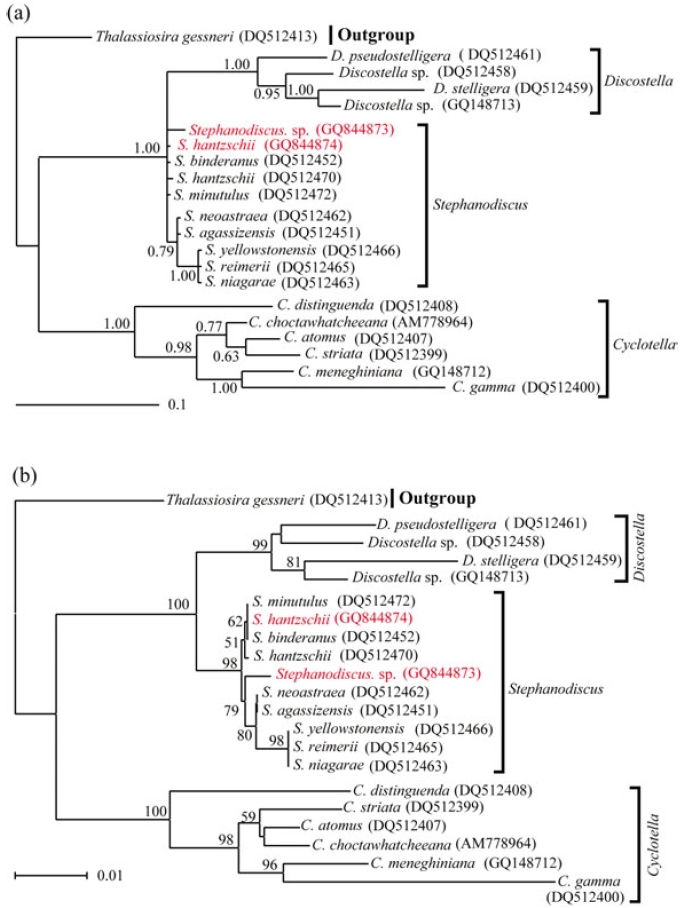

Molecular relationships of three major freshwater centric diatoms, namely Cyclotella, Discostella and Stephanodiscus, were inferred from Bayesian, Neighbor-Joining analyses, using their available 18S and partial 28S rDNA sequences, respectively (Figs 2, 3). Recently, we reported the phylogenetic relationships of Cyclotella and Discostella, in which phylogenetic trees were inferred with Bayesian method, using 18S and 28S rDNA data (Jung et al. 2009). In the present study, the author focused on Stephanodiscus relationships against the two other genera, as well as inter-species relationships within the genus Stephanodiscus. Considering our previous work (Jung et al. 2009), the author constructed new data matrices, including certain members of Cyclotella and Discostella. In the present analyses, a total of 20 species, including six Cyclotella, four Discostella and ten Stephanodiscus, with the outgroup of Thalassiosira, were subjected to phylogenetic analyses with Bayesian and NJ methods (Fig. 1). Phylogenetic analyses showed that the three genera included here were well separated (1.00 PP, 100% BP). Overall topologies of the Bayesian tree were compatible with those of the NJ tree. All the species of Stephanodiscus formed a cluster (1.00 PP, 100% BP), of which clade was separated from a Discostella cluster. Stephanodiscus and Discostella are a sister relationship, separating a clade of Cyclotella, showing that these patterns were in agreement with Alverson et al. (2007). In the Stephanodiscus linage, most species, excluding a cluster of S. niagarae, S. reimerri and S. yellowstonensis, formed a polytomy including six species. These were caused by low genetic divergences and high DNA similarities, detected in Table 3. Within this linage, a Korean Stephanodiscus isolate was positioned at an early divergent place, clearly being separated from other Stephanodiscus (1.00 PP, 100% BP).

[Fig. 1.] Phylogenetic relationships of three centric diatom genera, Cyclotella, Discostella, and Stephanodiscus, inferred by nearly complete18S rDNA sequences with (a) Bayesian and (b) NJ algorithms, respectively. Both analyses were used as the same datamatrix, with different nucleotide substitution models (e.g. GTR + I + G in Bayesian, and Maximum Composite Likelihood in NJalgorithm). Likelihood scores as the Bayesian tree were calculated at ?lnL = 3,898.6. The centric diatom, Thalassiosira gessneri#AN02-08 (GenBank no. DQ514864), was used as the outgroup. Bayesian posterior probabilities less than 0.50 and bootstrap proportionless then 50% were not shown.

In addition to this, phylogenetic analyses of partial 28S rDNA of the three centric diatom groups showed similar branch patterns, when compared with those of 18S rDNA phylogenies. Stephanodiscus was a sister relationship with Discostella, of which clade was clustered with Cyclotella (1.00 PP, 100% BP). Within theses analyses, Stephanodiscus formed a polytomy, excluding a cluster of S. niagarae, S. reimerii and S. yellowstonensis (Fig. 2). The 28S rDNA phylogeny showed that the Korean isolate was not separated from other Stephanodiscus. Overall 28S phylogeny was in good accordance with the 18S phylogeny described above.

[Fig. 2.] Phylogenetic relationships of three centric diatom genera, Cyclotella, Discostella, and Stephanodiscus, inferred by partial 28SrDNA sequences with (a) Bayesian and (b) NJ algorithms, respectively. Both analyses were used as the same data matrix, withdifferent nucleotide substitution models (e.g. GTR + I + G in Bayesian, and Maximum Composite Likelihood in NJ algorithm).Likelihood scores of Bayesian tree was calculated at ?lnL = 2,296.2. The centric diatom, Thalassiosira gessneri #AN02-08 (GenBankno. DQ512413), was used as the outgroup. Bayesian posterior probabilities less than 0.50 and bootstrap proportion less then 50%are not shown.

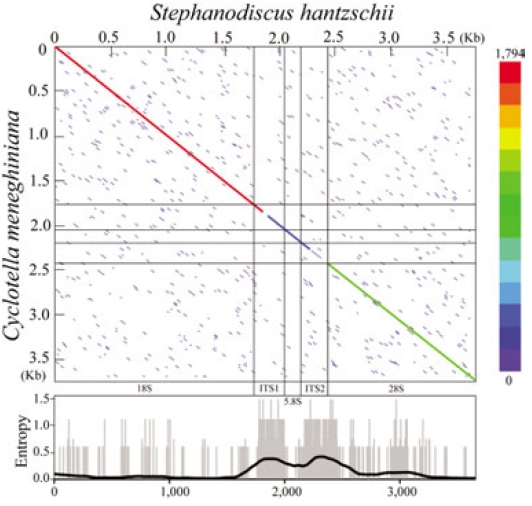

The present rDNA sequences of Stephanodiscus were graphically compared with those of the Cyclotella sensu lato, by using dot-matrix and entropy-plot analyses (Fig. 3). Here the dot-plot was obtained using sliding windows of 60 nucleotides along the compared rDNAs. The plot showed a clear distribution of both variable and conserved positions along the rDNA sequences: the coding regions were conserved, the other non-coding regions were highly variable (Fig. 3). This was in good accordance with our previous study (Jung et al. 2009).

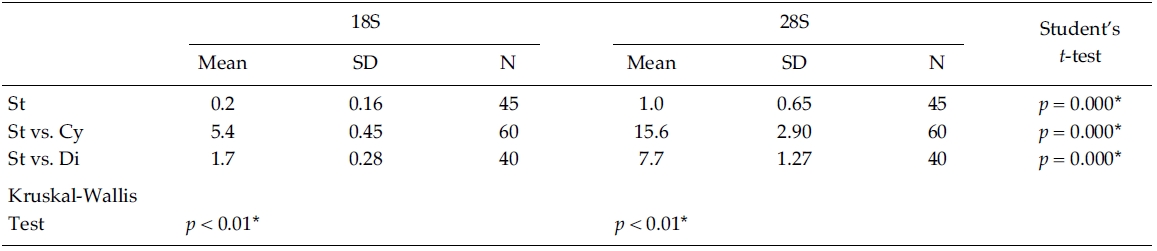

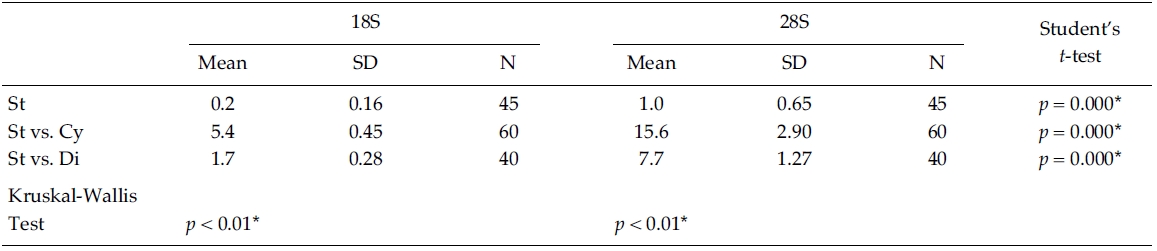

Nucleotide divergences of the 18S and 28S rDNA sequences were compared, using pairwise genetic distances calculated with the Kimura two-parameter model (Table 4). In most cases, DNA divergences within nine Stephanodiscus (listed in Table 3) were considerably low both in 18S (less than 0.2%) and in 28S rDNA (less than 1.0%). By comparisons, divergences of the 28S rDNA were significantly different compared to the 18S rDNA (Student’s t-test, p = 0.000). In addition, divergences of individual 18S, 28S rDNA among the three groups, Cyclotella, Discostella, and Stephanodiscus, were significantly different according to the Kruskal-Wallis Test (p < 0.01). By comparisons of Stephanodiscus with Cyclotella and Discostella, high genetic divergences were calculated from 18S (Stephanodiscus versus Cyclotella, 5.4%, SD = 0.45) and 28S rDNA (Stephanodiscus versus Cyclotella, 15.6%, SD = 2.9). These support that Stephanodiscus has high similarities of both 18S and 28S rDNA (Table 3), but Cyclotella and Discostella shows low similarities in both genes (Jung et al. 2009).

The centric diatoms, including Cyclotella, Discostella, and Stephanodiscus, commonly occur in freshwaters, including the Han River (Han et al. 2002; Jung et al. 2009). According to the previous studies (Kim 1998; Han et al. 2002), high abundance of the centric diatoms were frequently observed in water samples collected from Paldang Reservoir and Han River during early spring. Some blooms were caused by Cyclotella and Discostella (e.g. Jung et al. 2009), and sometimes Stephanodiscus blooms occurred in Paldang Reservoir (Kim 1998; Han et al. 2002). The blooming Stephanodiscus in Paldang Reservoir were morphologically considered as S. hantzschii (Han et al. 2002). In addition, the author isolated a Korean Stephanodiscus cell (KHR001) from a water sample of Paldang Reservoir when Stephanodiscus cells were present predominantly, and identified them as S. hantzschii, judging by routine morphological observa-tions and previous reports (Kim 1998; Han et al. 2002). However, comparative molecular data done with BLAST searches and similarity scores (Table 3) were not in accordance with morphological identity. Upon rDNA comparisons between Stephanodiscus sp. #KHR001 with other S. hantzschii (the present UTCC 267, WTC21, ATN2), the present Korean isolate should be a different species, than S. hantzschii, judging from the present phylogenetic analyses and molecular similarities (Table 3; Figs. 1, 2). Previously, Kim (1998) discriminated three species of Stephanodiscus, e.g. S. hantzschi f. tenuis, S. parvus, S. invistatus, from spring water samples of Paldang Reservoir. These suggest that the blooming species may be some of these recorded species (e.g. S. hantzschii, S. hantzschi f. tenuis, S. parvus, S. invistatus) possibly including unrecorded species, while S. hantzschii have been considered only to be the blooming species in Paldang Reservoir for a long time. Thus, existing ecological and morphological discrimination of the blooming Stephanodiscus may be reinvestigated, considering the present molecular data available.

In conclusion, the present study determined longrange sequences of rDNA from S. hantzschii #UTCC 267 and a Korean Stephanodiscus sp. #KHR001. Molecular comparisons showed high genetic similarities (or low genetic divergence) within the genus Stephanodiscus compared with those of Cyclotella and Discostella. From these facts, the author concludes that nuclear rDNA sequences of Stephanodiscus are considerably similar to each other, but they are significantly different (p < 0.01) from other freshwater centric diatoms (e.g. Cyclotella and Discostella).