The freshwater red algal order Thoreales is distinguished from the closely related Batrachospermales by its multiaxial rather than uniaxial gametophytes (Müller et al. 2002). The thallus consists of a central medulla of colorless filaments surrounded by determinate assimilatory filaments. The order is monotypic and includes two genera, Nemalionopsis and Thorea (Starmach 1977, Sheath et al. 1993, Müller et al. 2002). These two genera of the Thoreaceae are distinguished by the positioning of the reproductive structures (sporangia) and arrangement of the assimilatory filaments in the outer region (Sheath et al. 1993, Necchi and Zucchi 1997, Entwisle and Foard 1999, Carmona and Necchi 2001): assimilatory filaments are densely arranged and sporangia are located on outer assimilatory filament in Nemalionopsis, whereas in Thorea the filaments are loosely arranged and sporangia are located in the inner assimilatory filaments. Sexual reproduction and carposporophytes have been described in Thorea (Yoshizaki 1986, Necchi 1987, Sheath et al. 1993, Necchi and Zucchi 1997, Entwisle and Foard 1999, Carmona and Necchi 2001) and carpogonia and putative spermatangia were only recently reported in Nemalionopsis from Indonesia (Johnston et al. 2014).

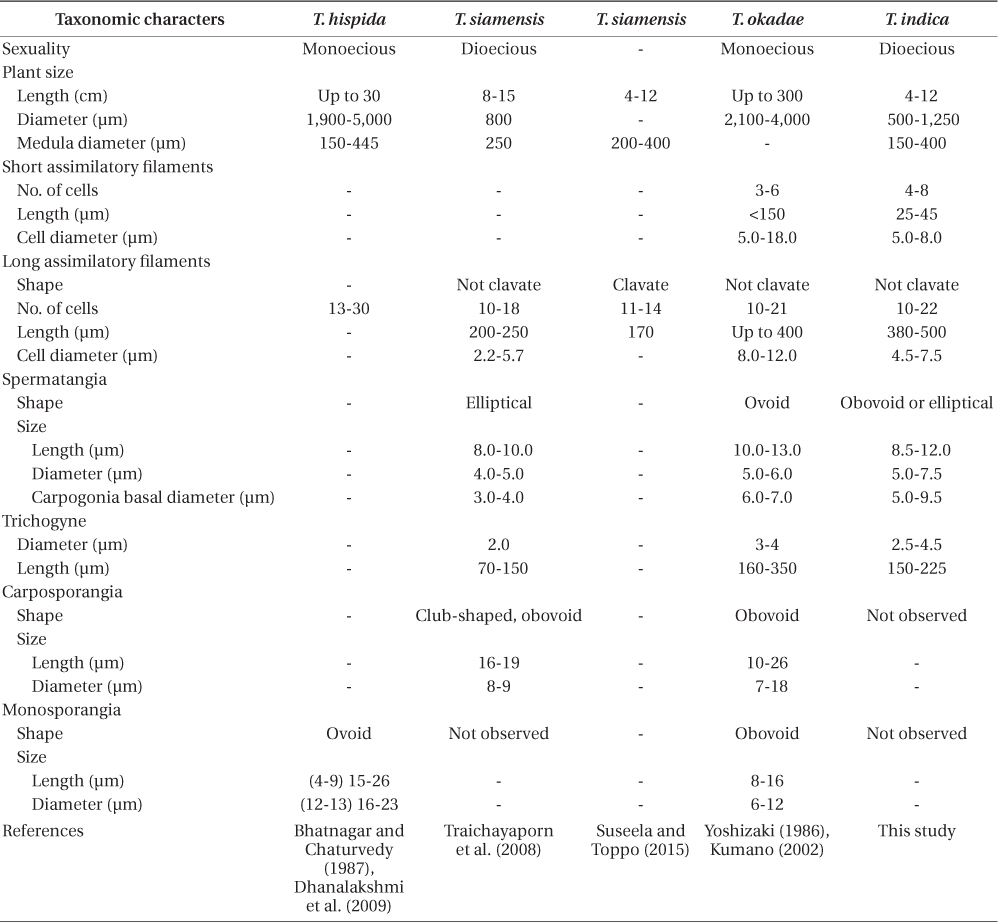

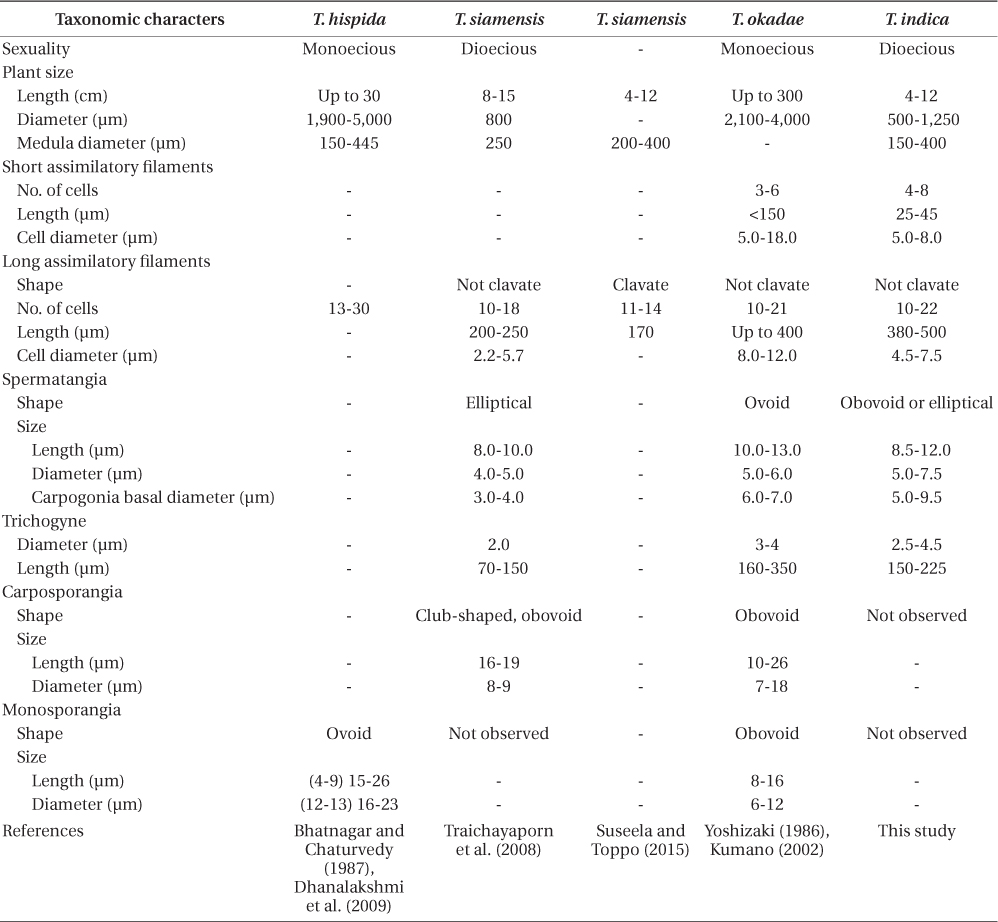

Thorea species have been reported in several regions of the world but tend to be more common in tropical, subtropical and warm temperate areas with hard waters (Sheath and Hambrook 1990, Sheath et al. 1993, Necchi et al. 1999, Carmona and Necchi 2001). Taxonomic characters used for species delineation are mostly vegetative features (Sheath et al. 1993, Carmona and Necchi 2001, Necchi et al. 2010a): plant and medulla diameter, branching frequency (abundant or sparse secondary branches), size and shape of assimilatory filaments (clavate or non-clavate), size and shape of sporangia. However there is considerable overlap in these characters, causing problems in species identification (Carmona and Necchi 2001, Necchi et al. 2010a). Characteristics of sexual reproduction (carpogonia and spermatangia) and carposporophytes may provide a more reliable set of diagnostic characters but as yet these features are poorly documented for most species.

Guiry and Guiry (2015) list 12 accepted species of Thorea. Twenty-two years ago Sheath et al. (1993) recognized only four species of Thorea worldwide: T. clavata Seto et Ratnasabapathy, T. hispida (Thore) Desvaux, T. violacea Bory, and T. zollingeri Schmitz. Since then T. siamensis Kumano & Traichaiyaporn (Traichaiyaporn et al. 2008) from Thailand, T. conturba Entwisle & Foard (1999) from Australia, and six species (including some taxa considered as synonyms by Sheath et al. [1993]) summarized in Kumano (2002): T. bachmannii Pujals, T. brodensis Klas, T. gaudichaudii C. Agardh, T. okadae Yamada, T. prowsei Ratnasabapathy et Seto, and T. riekei Bischoff.

Studies using molecular data are still inadequate for the genus. Müller et al. (2002) found the following sequence divergence among species of Thorea for two molecular markers: 5.4-13.3% for rbcL (plastid gene encoding the large RuBisCO subunit) and 2.5-13.3% for small subunit (SSU) rDNA (nuclear gene encoding the large ribosomal subunit). They recognized four species based on these two markers, which could not be properly named because it was impossible to distinguish T. hispida from T. violacea in distinct geographic origins. Necchi et al. (2010a) found that Thorea had four major clades based on sequences of rbcL and SSU rDNA, each one representing a distinct species: 1) T. gaudichaudii from Asia (Japan and Philippines); 2) T. violacea from Asia (Japan) and North America (USA and Dominican Republic); 3) T. hispida from Europe (England) and Asia (Japan); 4) T. bachmannii from South America (Brazil). In addition, they pointed out that Thorea species recognized by molecular data require additional characters (e.g., reproductive details and chromosome numbers) to allow consistent and reliable taxonomic circumscriptions.

Singh (1960) reported briefly on the occurrence of T. hispida (= T. ramosissima) for the first time from North India. Khan (1978) added some details on thallus anatomy and noted the presence of a single monosporangium, which Desikachary et al. (1990) doubted. Bhatnagar and Chaturvedi (1987) made some important observations on the sexual apparatus of T. hispida (as T. ramosissima). Importantly they stated clearly that ‘spermatangia and carpogonia are found to form on the same plant, i.e., their specimens were bisexual or monoecious. Dhanalakshmi et al. (2009) studied T. hispida (as T. ramosissima) collected from a waterfall in the Andaman and Nicobar islands, but did not specify whether their plants were uni- or bi-sexual. A noteworthy collection of T. hispida (as T. ramosissima) is from a land locked lake at a high altitude (4,266 m) in Ladakh, Indian Himalayas (Bhat et al. 2011). Suseela and Toppo (2015) reported T. siamensis from the Sai River, Uttar Pradesh, India among other three freshwater red algal species. Feng et al. (2015) analyzed T. hispida from two cool temperate sites in Shanxi, China based on sequences of two genes (rbcL and SSU rDNA).

To identify the newly collected material of Thorea required morphological and molecular comparisons with not only Indian collections (where possible) but with those from elsewhere in the world.

Thorea specimens were collected by K. Toppo (collection No. SAI 201102) on March 13, April 3, and April 24, 2014 from the Sai River, Uttar Pradesh, India (26°39′00.7″ N, 80°47′38.3″ E) at an elevation of 106 m. For morphological studies, the materials were preserved in 4% formalin with voucher specimens mounted on herbarium paper and lodged at Herbaria MEL, MICH, and SJRP (herbarium acronyms follow Thiers 2015). Specimens for DNA analysis were blotted dry with tissue and preserved in silica desiccant. Morphological analyses were carried out for all characters previously used as diagnostic in relevant studies of the genus (Yoshizaki 1986, Necchi 1987, Sheath et al. 1993, Necchi and Zucchi 1997, Kumano 2002). As a rule, twenty measurements or counts were taken for each character in each sample (Necchi and Zucchi 1997). For microscopic observations mounting media including stains were prepared as follows: 1) 0.02% aniline blue WS in 50% corn syrup and 0.5% phenol (Ganesan et al. 2015), specimens added for 30 min, removing water carefully with blotting paper, adding a drop of mounting medium and arranging the specimens with a fine needle and forceps tip; 2) a double staining of 1% aqueous methylene blue (Grimstone and Skaer 1972) and 1% alcian blue (Sheath and Cole 1990) by placing small pieces for 10 min in each solution. Surface views, cross and longitudinal sections were prepared on microscope slides after staining. Photographs were taken with Canon G3 camera (Canon, Tokyo, Japan) adapted to a Zeiss binocular research compound microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) and a Leica DFC 320 digital camera with a LAS capture and image analysis software coupled to a Leica DM 5000 microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

For DNA extraction, samples were ground with a Precellys 24 tissue homogeneizer (Bertin Technologies, Montigny- le-Bretonneux, France), followed by DNA extraction using NucleoSpin plant II mini kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany). A 1,282 bp fragment of the plastid-encoded ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase–oxygenase large-subunit gene (rbcL) was polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplified using the set of primers specified by Vis et al. (1998). The 664 bp barcode region near the 5′ end of the cox1 gene was PCR amplified using the M13 F and R primers (Saunders and Moore 2013). PCR reactions were tested for the two markers as follows: 25 μL Top Taq Master Mix (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany), 2.0 μL each primer, 4.0 μL dH2O, and 2.0 μL extracted DNA. The PCR protocols for the rbcL and cox1 barcode region gene followed Vis et al. (1998) and Saunders and Moore (2013), respectively. PCR products were purified using the NucleoSpin Extract II (MN, Macherey-Nagel) PCR clean up or Gel Extraction. Sequencing was performed using the amplification primers for both markers, and in addition the internal rbcL primers R897 and F650 (Vis et al. 1998). Sequencing reactions were run using the ABI PRISM Big Dye v3.1 Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit and the ABI PRISM 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Sequence alignments were assembled in Geneious 7 (Kearse et al. 2012). For phylogenetic analyses of the rbcL data a GTR + I + G was determined as the best-fit model of sequence evolution by the Akaike Information Criterion using jModelTest 2.1.4 (Darriba et al. 2012). Maximum-likelihood (ML) topologies and bootstrap values from 10,000 replicates were inferred using RAxMLGUI (Silvestro and Michalak 2012) and bayesian analysis (BA) was performed using MrBayes 3.2 (Huelsenbeck and Ronquist 2001) as plugin for Geneious. BA consisted of three runs of five chains of Metropolis coupled Markov Chain Monte Carlo for 10 × 106 generations. The first 500 trees were discarded as burn-in.

The cox1 marker sequence was compared to other red algal barcodes available in databases: the barcode of life data systems (BOLD) database (Ratnasingham and Hebert 2007) and GenBank (Benson et al. 2013).

Comparison of the cox1 barcode sequence from our Indian specimen with those in GenBank database returned the following close matches (Appendix 1): 90.8% with Thorea sp. (KC130141) (Scott et al. 2013) from Australia; 90.4% with T. hispida from Hawaii (KC596320) (Carlile and Sherwood 2013) and from China (KC511076) (unpublished). BOLD database returned no close matches (> 85%). These results indicate that the sequence from the Indian specimen belongs to a species quite distinct from any previously sequenced samples.

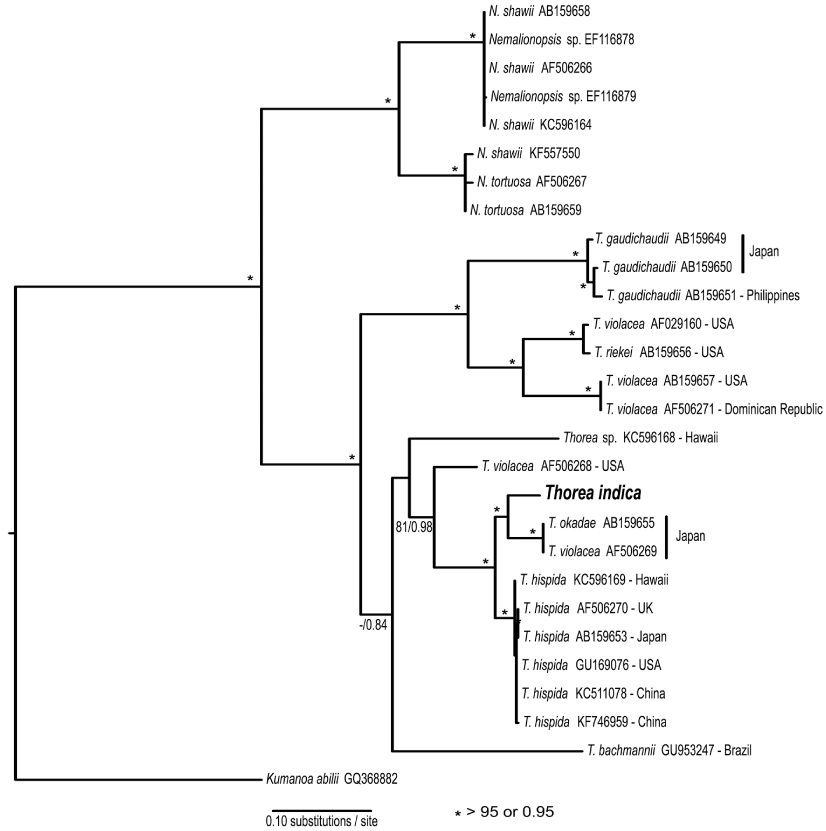

The rbcL gene sequence from India was compared with 18 previously published sequences of Thorea obtained from GenBank (Appendix 1). BA and ML analyses of the rbcL alignment yielded similar trees, showing strong support for Nemalionopsis and Thorea as monophyletic groups (Fig. 1). Within the genus Thorea nine clades were revealed, that we interpreted as different species. The sequence of Indian specimen was positioned in a major clade with high support containing two other species: T. okadae from Japan and T. hispida from continental USA, Hawaii, the UK, and China. The divergences among these sequences were as follows: India vs. T. okadae (2.8%, 35 bp); India vs. T. hispida (2.9-3.4%, 37-44 bp). The two samples of T. okadae are identical and the reference of sequence AF506269 as T. violacea (Appendix 1) was probably a misidentification. These divergence levels are high enough to consider the Indian specimen as a distinct species that we describe below.

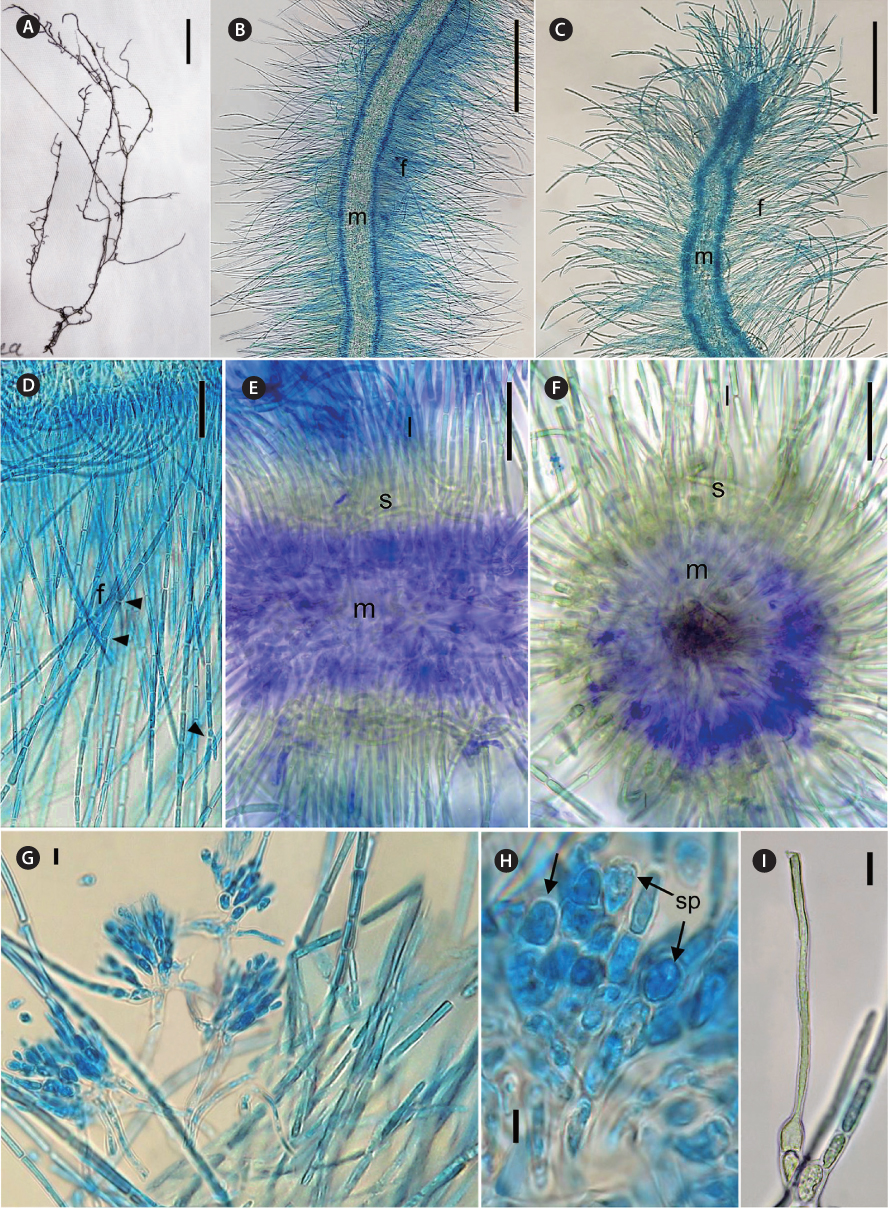

[Fig. 2.] Thorea indica morphological characters. (A) General view of pressed holotype. (B) Mid portion of a mature plant showing assimilatory filaments (f) and medulla (m). (C) Apex of a mature plant, showing assimilatory filaments (f) and medulla (m). (D) Longitudinal section showing assimilatory filaments (f ) and branches (arrowheads). (E) Longitudinal section showing medulla (m), short (s) and long (l) assimilatory filaments. (F) Cross section showing medulla (m), short (s) and long (l) assimilatory filaments. (G) Spermatangia in clusters on short assimilatory filaments. (H) Detail of spermatangia (sp, arrows). (I) Carpogonium on 1-celled carpogonial branch. Staining: aniline blue (B-D, H & I); double methylene blue and alcian blue (E & F). Scale bars represent: A, 10 mm, B & C, 250 μm; D, 25 μm; E & F, 50 μm; G & I, 10 μm; H, 5 μm.

Diagnosis. Plants dioecious, moderately mucilaginous, 4-12 cm in length, dark brown to brown-greenish, moderately to abundantly branched, multiaxial, attached to substrata by discoid holdfasts. Male plants slender and abundantly branched, 500-900 µm in diameter; female plants larger and moderately branched, 700-1,250 µm in diameter. Thallus structure consisting of a central medulla, with interwoven colorless branched and twisted filaments with short often irregularly shaped cells. Medulla 150-400 µm in diameter. Outer medulla a ring of long parallel filaments, with irregularly sized cells 2-4 µm in diameter. Cortex composed of short and long assimilatory filaments in an outer whorl at right angle to the main shoot. Short assimilatory filaments 25-45 µm long, composed of 4-8, short barrel-shaped to cylindrical cells, 5-8 µm diameter; long assimilatory filaments, sparsely branched, with 10-22 cylindrical cells of uniform diameter (4.5-7.5 µm) along each filament length, 380-500 µm in length. Each cell appears to have a single multi-lobed peripheral chloroplast. Spermatangia arising from the short assimilatory filaments, usually developing in clusters or less often in two, obovoid or elliptical, 8.5-12.0 µm in length, 5.0-7.5 µm in diameter. Carpogonia bottle-shaped or ovoid, 5.0-9.5 µm in diameter, inserted directly on the basal cell of assimilatory filaments or on one discoid or barrel-shaped cell; trichogynes elongate and filiform, 2.5-4.5 µm in diameter and 150-225 µm in length. Monosporangia, carasposporangia and ‘Chantransia’ stage not observed.

Holotype. India, Uttar Pradesh, Sai River, coll. K. Toppo, Mar 13, 2014 (MEL2389295); isotype SJRP 31508.

Habitat. Moderately flowing, clear stream; alga growing at depth of 1-2.5 ft, attached to submerged stones.

The two genera in the Thoreales can be separated on reliable morphological characters, but species of Thorea are hardly distinguishable on the basis of morphological features, as pointed out in previous studies (Carmona and Necchi 2001, Necchi et al. 2010a). Wide overlap of morphological and morphometric characters are usually observed among species, leading to difficulties for species circumscriptions. Plant and medulla diameter are largely used but are not reliable criteria to differentiate species as Thorea is apparently seasonal in tropical and temperate regions with dimensions changing according to the season (see Simić et al. 2014). Branching pattern, i.e., abundant vs. sparse secondary branches, has also been demonstrated to be unreliable for species delineation (Carmona and Necchi 2001). One of the few vegetative characters that seems to be useful for species identification is the shape of assimilatory filaments, i.e., clavate vs. non-clavate, the former being exclusive of T. clavata and T. zollingeri.

Monosporangia, spermatangia, carpogonia, and carposporophytes can be potentially valuable as additional diagnostic characters for species identification in the genus. However, detailed descriptions of these characters have been poorly documented in most studies. In addition, monosporangia are probably misinterpreted by some authors as spermatangia or carposporangia. Monosporangia and carposporangia frequently have similar shape (obovoid to elliptical) and overlapping size ranges, thus care should be taken to distinguish between these two. Monosporangia can be easily differentiated from spermatangia by their granular content and larger size (Carmona and Necchi 2001). The existence of monosporangia in Thorea as the sole means of reproduction was questioned by Necchi (1987) and Necchi and Zucchi (1997), as they could so easily be mistaken for spermatangia or carposporangia. More recently the coexistence of monosporangia with sexual reproductive structures (carpogonia and spermatangia), as well as carposporangia, was confirmed by Carmona and Necchi (2001). They were borne singly or in pairs on undifferentiated branches, arising from the proximal cells of the assimilatory filaments. Although monosporangia are produced terminally at the bases of assimilatory filaments, they have been reported at the apex of the long assimilatory filaments (Entwisle and Foard 1999, Xie and Shi 2003). The former authors termed them as archeospores, as defined by Nelson et al. (1999).

Necchi et al. (2010a) found that four species of Thorea could be recognized based on sequences of rbcL and SSU rDNA: 1) T. gaudichaudii from Asia (Japan and Philippines); 2) T. violacea from Asia (Japan) and North America (USA and Dominican Republic); 3) T. hispida from Europe (England) and Asia (Japan); 4) T. bachmannii from South America (Brazil). They pointed out that T. okadae from Japan (Hanyuda et al. unpublished data) did not form a separate branch, but grouped together with samples from Japan and England (Müller et al. 2002). Thus, they proposed that T. okadae should be treated as a synonym of T. hispida and not of T. violacea. However, in this study we found that T. okadae forms a quite distinct clade, sister of the new species T. indica (Table 1, Fig. 1). Both formed a sister clade of T. hispida from the UK, the continental USA and Hawaii. In summary, nine species can be recognized from molecular data: T. bachmannii from Brazil, T. gaudichaudii (from Japan and the Philippines), T. hispida (from the UK, the continental USA, Hawaii, and China), T. okadae (from Japan), T. riekei (from USA), T. violacea (from USA), T. indica and an undetermined species–Thorea sp. from Hawaii (Carlile and Sherwood 2013) and the continental USA reported as T. violacea (AF506268) (Müller et al. 2002). A clear geographic distribution is evident for most Thorea species based on molecular data. This could be used as an additional criterion to distinguish them, considering the little value of the currently used morphological characters discussed above.

The comparison with previous reports from India (Table 1) is not conclusive, mostly due to the inadequate descriptions provided and lack of molecular evidence. The specimens previously reported as T. hispida fit within the circumscription of T. indica and we recommend their tentatively placement in this species. The report of T. siamensis by Suseela and Toppo (2015) from the same locality as T. indica has no morphological basis, either in comparison with the original description (Traichaiyaporn et al. 2008) or data from this study (Table 1). Relevant vegetative characters were not presented, particularly plant diameter and short assimilatory filaments. They described assimilatory filaments as being clavate (cell diameter enlarging from proximal to distal part), which is exclusive of T. clavata and T. zollingeri, and quite different of T. siamensis. In addition, the reported value of as similatory filament length (170 μm long) is much shorter than reported for T. siamensis (200-250 μm) (Traichaiyaporn et al. 2008) and other species reported from India or phylogenetically related (Table 1). We presume the measurement was taken in mistake or from young parts. They made no reference to spermatangia, carpogonia or carposporophytes.

Thorea indica is comparable to T. siamensis in being dioecious and in plant size (length and diameter), medulla diameter, shape and number cells of assimilatory filaments (Table 1). However, T. indica has longer assimilatory filaments (380-500 µm × 200-250 µm), larger spermatangia (5.5-7.5 µm × 4.0-5.0 µm in diameter), larger carpogonia (5.0-9.5 µm × 3.0-4.0 µm of basal diameter) and longer (150-225 µm × 70-150 µm long) and wider (2.5-4.5 µm × 2.0 µm in diameter) trichogynes (Table 1).

In summary, the description of specimens from the Sai River by Suseela and Toppo (2015) is very incomplete, whereas the data reported fit within our description of T. indica. The specimens of T. hispida and T. okadae are sister to our new species and are distinguished by minor morphometric characters and sexuality (dioecious vs. monoecious).