축제나 이벤트는 방문자에서 그 지역의 독특한 문화와 분위기를 즐길 수 있는 물리적 공간을 제시할 뿐만 아니라, 지역의 이미지를 전달 할 수 있기 때문에, 지역커뮤니티의 독특한 특성과 정체성을 브랜드를 지역축제에 반영할 필요가 있다. 따라서 본 연구는 서울 하이! 서울페스티벌을 중심으로 서울의 도시 이미지와 정체성이 축제를 통해 잘 반영되고 있는지를 실무자 및 지역주민, 방문객을 중심으로 분석하고, 축제를 통해 방문객이 인지하는 이미지의 강점과 약점을 평가하여, 서울시의 정책관리자 및 축제 실무자에게 유용한 정보를 제공하고자 하였다. 연구목적을 달성하기 위해, 정성적 기법을 사용하였으며, 현재 서울에 거주하는 시민과 방문 경험자와의 심층 인터뷰를 실시하였고, 하이! 서울페스티벌 관계 실무자와의 전문가 인터뷰를 실시하였다, 내용분석을 통해 본 연구에서 수집한 데이터를 분석하였고, 연구 결과에 따르면, 지역사회의 정체성은 일반적으로 하이! 서울페스티벌의 브랜드로 반영 된 것으로 나타났고, 인터뷰 분석결과는 하이! 서울페스티벌의 이미지를 ‘일관성’, ‘문화적 다양성과 국제화’, ‘열린 마음과 친절함’으로 나타났다. 본 연구의 결과는 하이! 서울페스티벌 방문객, 지역주민, 관계실무자의 공동된 의견을 중심으로 제공한 것이며, 하이! 서울페스티벌의의 지역정체성의 반영에 대한 현황을 확인하고, 축제 브랜드를 지원하기 위해 궁극적으로 축제에 지역사회의 정체성을 반영에 대한 기본자료를 제공하며, 이와 관련된 결과를 바탕으로 시사점을 논한다.

Considerable research has shown that destination images that are in accordance with the destination brand significantly influence tourism (Tapachai & Waryszak, 2000), and festivals are considered to be an effective—and one of the quickest—way to form destination images because of their potential to draw the attention of global media to the host city in a relatively short period of time (Bowdin, Allen, O’Toole, Harris, & McDonnell, 2006; Hyun, 2010). While Bowdin et al. (2006, p. 73) pointed out that festivals are an “opportunity to assist in creating, changing or reinforcing destination brand,” festivals created for this reason run the risk of becoming reproductions of other tourist destinations’ festivals (Richards & Wilson, 2006), with the result that the importance of the local community’s unique identity is overlooked (Quinn, 2005).

Bowdin et al. (2006) asserted that festivals must reflect the genuineness and uniqueness of the local community if they are to attract tourists. In addition, the festival’s brand identity should originate from the identity of the local community since a brand is created by and emerges from the people themselves (Gilmore, 2002; Lee at al., 2006). Therefore, while festivals themselves and festivals as a tool of destination branding must reflect identity of the local community, there is a lack of empirical study about to what extent community identity is reflected in festivals employed for the purpose of destination branding (Kwon & Park 2013; Nepal, 2008).

Since it is the local community that communicates with visitors and adds a unique atmosphere to the festival (Dredge & Jenkins, 2003, 2007), it is important for destination marketing organizations (DMOs) to know what the community identity is and how it can be reflected in destination branding and in the festivals themselves to boost the destination’s image as a tourist destination. By considering these factors, DMOs could gain the support of the local community, which is essential to the sustainability of festivals (Getz, 2007), but also the support of cultural tourists who seek authenticity in their destinations (Real, 2000). By reflecting their true identity in their brand identity, communities can also strengthen their pride, which will positively influence the communities’ attitudes toward visitors (Getz, 2007). Given the scarcity of research on community identity in festivals held for the purpose of destination branding, the current study uses a case study of the Hi! Seoul Festival in Seoul, South Korea, to provide insight into the importance of community identity in festivals held for destination branding. In addition, by assessing Seoul’s strengths and weaknesses in portraying its image in festivals, the study provides information to other DMOs that are planning or holding festivals as a way of destination branding.

1. Community Identity in Destination Branding

Brand community identity is defined as the host community’s common perceptions, values, and sense of place based on a geographical place that is marketed as a travel destination (Ballesteros, 2007; Pike, 2008). In discussions of community identity, it is important to define ‘sense of community’ and ‘sense of place’ (Derrett, 2003; Pike, 2008), which constitute large part of community identity (Derrett, 2003). ‘Place’ is a certain space occupied by people (Derrett, 2003). Studies have shown that reorganizing their attachment to a place affects people’s sense of stewardship of a place (Derrett, 2003; Pike, 2008). A place can have personal traits that generate emotional attachment, including its natural landscape, the built environment, the climate, and shared memories of communal heritage (Derrett, 2003). Derrett (2003) stated that such memories and sense of place shape individuals who compose the community. In this context, Gu and Ryan (2008) observed that the Western academic literature on tourism often underestimates the role of place attachment and the contribution of sense of the place. Gu and Ryan (2008) noted that the concept of place attachment has been used to explain visitor behaviors, especially repeat visits, and argued that it can be applied conversely to local residents. Just as tourists develop emotional links with a destination when they visit it (Nepal, 2008), communities can possess a strong sense of co-operative and community identity based on their networks in the place, which can be seen as an extension of the family relationship (Gu & Ryan, 2008).

Sense of place leads to the sense of community that is a critical part of a healthy community and its identity (Derrett, 2003). Sense of community generally includes the residents’ image of the community, its spirit, character, pride, relationships, and networking. It is built over time and comes from a shared vision and common experiences (Ballesteros & Ramirez, 2007) that provide individual with clear sense of purpose and inspire them to work together on community issues, solve communal problems, and celebrate. Sense of community, influenced by sense of place, affects a community’s wellbeing, which inspires the atmosphere in which individuals and community define their values and beliefs (Derrett, 2003). Therefore, it could be said that sense of community is interrelated with community identity and that each influences the other. This sense of community and community identity are also known to affect the formation of individual identity and vice versa (Ballesteros & Ramirez, 2007; Breakwell, 1992; Breakwell, 1986; Gu & Ryan, 2008).

Henderson (2006) showed that attempts to redefine the identities of places as tourist destinations through branding have generated issues on motives and consequences from economic and political perspectives. Although such branding has implications for the life of the residents and their environment, they are not always considered in brand decisions. There is also criticism about commodifying destinations and their inhabitants such that they are treated as products that can be traded and consumed by tourists. This commodification leads to creation of attractive images of travel destinations that are misleading to tourists (Henderson, 2006). Henderson (2000, as cited in Pike, 2008) also asserted that places that are fabricated for tourist consumption and that lack authenticity are eventually recognised by visitors as such, and they will move on to look for authenticity elsewhere. Therefore, the identification of a community’s genuine brand is essential if the destination brand is to be effective (Pike, 2008). Anholt (2007, p. 75) also stressed the importance of the identity of the community’s brand, asserting that “the people are the brand—the brand reflects the genius of the people” and maintaining that the people and their characteristics, including education, abilities, and aspirations, are what makes the place what it is. These are the factors that create the potential for tourism, business, and cultural and social exchange. A place without some sense of its people and their particular nature is just an empty landscape (Anholt, 2007); it is the people who contribute to the unique qualities of place, the culture, and the tourist experience (Dredge & Jenkins, 2003, 2007).

Not only do local residents of a destination form the atmosphere of the place, they also provide human resources. Pike (2008) pointed out that brand community is an important brand communications medium in an advertising campaign, because it is the community that delivers the brand promise. Whether local residents like it or not, the intermediaries of the tourism products of a destination are the local community, and the local community is involved in tourism industry in many ways, including restaurants and shops (Donald & Gammack, 2007). Therefore, it is important in destination branding to build a memorable bond and emotional link between the target markets and the destination while respecting the community’s broader values, goals, and sense of place (Tasci & Kozak, 2006). Therefore, as Pike (2008) argued, it is critical to encapsulate the values of a community when branding a tourist destination.

2. Festival and Local Community in Destination Branding

Festivals enhance local continuity by creating opportunities to share histories of community, cultural customs, and ideas, and by building settings for social interactions (Quinn, 2005). Local residents play an important role in terms of human resources in festivals, as community involvement and its management are key factors in festivals and their planning processes (Steynberg & Saayman, 2004). Therefore, public relations and strong support by the community are required for the success of festivals in a destination area (Getz, 2007).

Community involvement encourages variation and local flavor in the nature of the tourist destination (Steynberg & Saayman, 2004), reflects the attitude and identity of local residents, increases community pride and spirit, enables the residents to create new vision of the place they live, and strengthens the community’s tradition and values (Getz, 2007; Quinn, 2005). If festivals are to be effective as tourist destinations, they must reflect genuineness and express the uniqueness of local residents (Bowdin et al., 2006), including their sense of community, identity, and place. Shallow events that do not reflect the community’s identity could damage the image of the destination and lead to its being regarded as inauthentic (Bowdin et al., 2006), which would be damaging to cultural tourism.

From this point of view, Donald and Gammack (2007) emphasized that every local resident is an ambassador, and if they do not believe in what the destination tries to represent as a brand, that disbelief will be reflected in the destination’s image. It is often the case that the local people’s attitude toward tourism, their intangible qualities (e.g., their culture), recreational attractions like local festivals, and the atmosphere of the destination are what attract tourists (Dredge & Jenkins, 2007; Donald & Gammack, 2007). Therefore, festivals provide the opportunity to help in creating, changing, or reinforcing the destination brand by reflecting those community identities (Bowdin et al., 2006). With its potential to draw the attention of global media to the host city, festivals are considered as one of the quickest way to form destination image (Getz, 2007).

Successful festivals make a contribution to travellers’ favourable perception of a destination and recognition of a place as a potential tourist destination on the tourism map and help a place to gain a lively and cheery image (Donald and Gammack, 2007). With their implications of joyfulness, sociability, and cheerfulness, festivals provide a ready-made set of positive images (Quinn, 2005). Therefore, festivals are often used to give people a sense the cultural atmosphere of a local destination and to deliver the impression of variety, activity, and sophistication (Getz, 2007). Destination managers use festivals because of the image associated with festivals, which could be transferred to the image of the host community and destination (Getz, 2007). Therefore, major festivals and events have become a standard destination-branding strategy (Getz, 2007; Richards & Wilson, 2006). However, perhaps because festivals are considered ‘quick fix’ solutions (Quinn, 2005) for shaping destinations’ images, they run the risk of duplicating other festivals (Richards & Wilson, 2004; 2006) and lacking any real connection with the destination, especially with the local residents (Quinn, 2005).

1. Research Design and Sample Selection

The study was conducted using a qualitative approach, as its purpose is to examine the congruity between community identity and the brand identity that DMO portrays through a festival as a way of destination branding. Reviewing previous research, many of the research regarding brand and brand image hires qualitative approaches. For example, Hanlan et al. (2004) adopted qualitative research, unstructured in-depth interviews specifically, in their study regarding destination image in Australia, claiming that qualitative approach is more suitable to deal with complex abstract issues such as image, attitudes and informant’s perspective on the topic. Prentice and Anderson (2003) used mainly interview followed by scaled items, and Blain et al. (2005) used questionnaire but specified that it is based on interviews. It is often the same case when it comes to the matter of studying identities. Derrett (2003) carried qualitative approaches in the research of identity of community, specifically narrative process, maintaining that it is suitable to understand the complexity of the elements that comprise a sense of community and place.

In this study, a qualitative approach was used to explore brand identity, which represents the value and essence of the destination community, and the image drawn by destination marketers. Brochures and tourist guidebooks published by Seoul City Council and the electronic brochure that is the official website of the Hi! Seoul Festival (Hi Seoul Festival, 2012) were used for content analysis (Pike, 2008). The findings of the content analysis were confirmed by three semi-structured interviews: one with a practitioner from the festival division and two with practitioners from the division of city marketing of Seoul City Council. Convenience sampling, which is suitable for an in-depth study that focuses on a small sample or a case selected for a particular purpose, was chosen to provide the researcher with an information-rich case study in exploring the research question (Saunders et al., 2007).

2. Interviews and Data Analysis

In-depth interviews with 21 local residents were conducted to explore the identity of the residents. These in-depth interviews had some characteristics of semi-structured interviews, since there were several topics to be covered and the researcher can follow-up on interesting and important issues that come up during the interview to sense interviewee’s identity (Smith & Eatough, 2007). The interviews took place in a couple of university campus, Yonsei University and Hongik University for example, and in cafes and parks in the center of the city, such as Myeondong, Sinchon, Jongno, Gwanghwamun and Cheonggyecheon. The researcher approached to citizens at those sites asked if they are citizens of Seoul and how many years they had been living in Seoul. Interviews were carried out right after interviewees consented to take part in the interviews. Interviews lasted 30-50 minutes, during which time interviewees were encouraged to speak freely about themselves and their daily lives. The interviewer had some flexibility in the questions asked, but questions were based on four themes: questions concerning significant events experienced by the interviewee while living in Seoul since, according to Crossely (2007), such events and how one perceives them define identity; questions concerning the interviewee’s sense of place and sense of community; questions concerning how the interviewee feels about Seoul and the people of Seoul; and questions regarding the interviewee’s perception of the Hi! Seoul Festival. Digital recordings of the interviews were transcribed verbatim into text for data analysis. Analysis was ongoing during the process of the survey, and emerging data were examined according to an iterative process that served both to inform the interviewing and establish concepts for subsequent analysis. The primary data from in-depth interview were analysed using narrative analysis. Narrative is defined as “a way of sharing information with others following a particular pattern of telling (genre and order)” (Marvasti, 2004, p.96). Narrative analysis includes the content that language means, but also includes the reason why the story was told in such way. Individuals construct things around them in personal narratives to claim identities and construct lives (Riesman, 1993). Hence, narrative analysis has to do with how the story teller interprets things and the researcher interpret his/her interpretations.

In qualitative research, trustworthiness including credibility, transferability, and dependability means the criteria of validity and reliability (Thompson, 2004). Credibility is an evaluation of whether or not the study findings represent a “credible” conceptual interpretation of the data drawn from the participants’ original data. This concept is related to internal validity, which means that qualitative researchers strive to explore what they intend to capture in order to enhance trustworthiness (Thompson, 2004). In line with credibility, data were directly quoted from the interview results in this study. Transferability is based on the belief that qualitative research findings need to be generalized and can be applied to other situations, and this could replace the concept of external validity (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004). The qualitative researcher can enhance transferability by doing the work, describing the research context, data collection, and the process of data analysis. Therefore, this study discussed theoretical and managerial implications, along with in-depth information about the data collected in order to provide insight into how individuals can apply findings to their own contexts and situations. Dependability is an assessment of the quality of the integrated processes of data collection, data analysis, and theory generation (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004; ). This is closely connected to the idea of reliability, which is based on the assumption of replicability or repeatability. Thus, this study collected data from a variety of sources; primary data (interviews with residents and organizers) and secondary data (brochures, tourist guidebooks, and the official website).

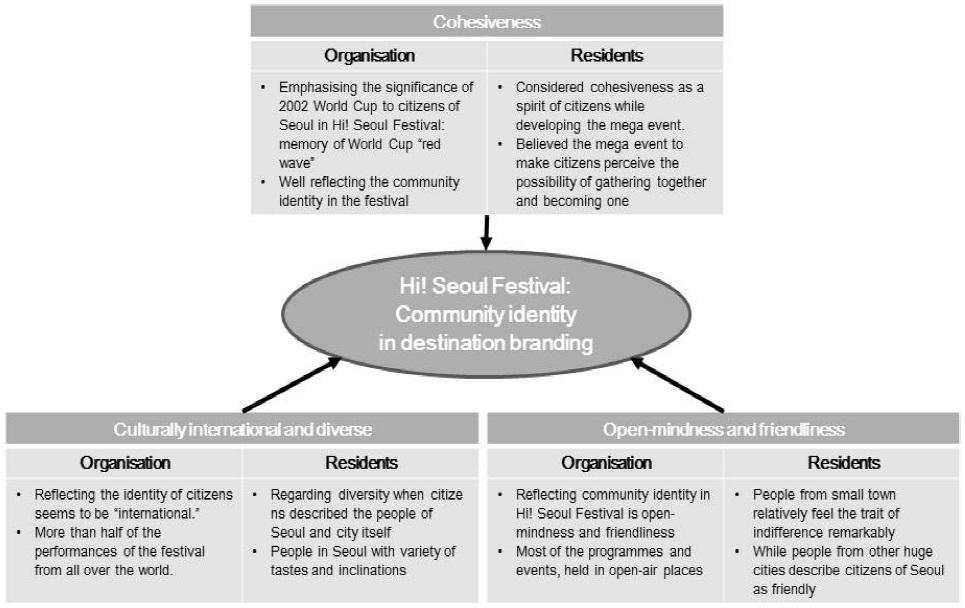

The findings from the qualitative survey, including the semi-structured interviews with practitioners in the organization and the in-depth interviews with local residents were classified into three major themes: cohesiveness, culturally international and diverse, and open-mindedness and friendliness.

The first image Seoul City Council tries to portray seems to be one of the cohesiveness of the citizens of Seoul. In explaining the history of the festival, the organization states, “The huge red wave that engulfed the downtown Seoul area during the 2002 FIFA World Cup Games showed the possibility of a festival that would attract citizen’s participation.” By putting emphasis on the “red wave” as the origin of the festival to depict unified citizens and their spirit, the website portrays an image of the unifying power and cohesiveness of Seoul’s citizens. Seoul City Council explains that, because of the memory of this “red wave,” representing cohesiveness, Seoul decided to hold the first Hi! Seoul Festival in May 2003 in place of the Seoul Citizens’ Day event. The Seoul Citizens’ Day event had been hold in October, but to remember the spirits of the citizens shown during the 2002 FIFA World Cup, Seoul City Council transformed that event into a new festival (Hi Seoul Festival, 2012) and moved it to May. Pictures of the “red wave” taken during the World Cup are found in every guidebook published by Seoul City Council introducing the Hi! Seoul Festival, so this image, representing the unity of the citizens, is a significant image in the festival.

The in-depth interviews also revealed this cohesiveness as part of the spirit of Seoul. Fifteen of the twenty-one participants responded to the question about a significant event with an experience related to the 2002 World Cup:

Fourteen interviewees used words like “unity,” “solidarity,” “became one” and “gathering,” to describe the meaning and the significance of 2002 World Cup. Other words they used were “passion,” “pride,” “festivity,” “fun” and “exciting.” Getz (2007) mentioned that important events strengthen the community identity, and Crossely (2007) asserted that significant events influence individuals’ identities, and the same would apply to the formation of community identity. Ballesteros and Ramirez (2007) also maintained that community identity emerges through common experience. The 2002 World Cup and street cheering seem to be enough of a common experience and significant event to the citizens of Seoul enough to form or strengthen the community identity, especially in terms of unity and cohesiveness.

Therefore, what Seoul City Council explains as the origin of Hi! Seoul Festival seems sound. The citizens of Seoul view the world cup as a significant event that makes them believe in the possibility of gathering together and becoming one. The interviewees’ mentioning the World Cup as the most meaningful event suggests that they value the unity and cohesiveness they experienced at that time, and this can be interpreted as one of the significant parts of the citizens’ community identity. By emphasizing this unifying power of citizens and the significance of the 2002 World Cup in information about the Hi! Seoul Festival, the Seoul City Council reflects cohesiveness as part of the community identity.

2. Culturally International and Diverse

Another image that Seoul City tries to portray in reflecting the identity of citizens is “international.” In the festivals held in 2010, 2011, and 2012, more than half of the performances in the festivals were by international artists (e.g., artists from France, Mongolia, China, Indonesia, Spain, Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom, Slovenia, and the Czech Republic). As the festival defines itself as an ‘international festival’, the content of the festival includes diverse genres of music, from western music like jazz to Korean traditional classic music, rather than focusing on a specific genre, such as jazz (Montreal, New Orleans), rock (Woodstock), techno (Detroit, Istanbul), or classical (Wien) music. It also includes all forms of dance, from break dancing to ballet and traditional dance, fashion, theatre, street performances, exhibitions and paintings, with no focus on any one place of origin or genre.

These content of the festival reflects the image of Seoul in terms of culture. In the brochure and guidebooks for tourists, Seoul is described as a place where “you can have it all”—whatever you hope for, whatever you want. The variety of content in the festival also reflects the diverse cultures of the citizens of Seoul, which is too diverse to focus on or collect as one. One interviewee from the festival division of Seoul City council explained that it is difficult to collect the tastes of Seoul’s citizens as one”

Clearly, Seoul City Council tries to reflect the cultural characteristic of the citizens in the festival by considering the culture of the community in the festival’s content. Derrett (2003) stated that characteristics of a community are among the elements in constructing community identity. Therefore, by reflecting the characteristics of citizens of Seoul in composing the festival’s content, Seoul City Council tries to reflect community identity in the festival.

Twenty of the twenty-one interviewees referred to diversity when they described the people of Seoul and the city itself. They mentioned words like “a variety of people with unique characteristics” and “people with a variety of tastes and inclinations.” They described the city as “a city of diversity with a lot of chances to enjoy a variety of cultures.” In addition, they commented that:

Quinn (2005) pointed out that glottalization of the city and that of its people are interrelated. Since the residents of the city exchange and compare experiences and ideas from outside of the city, they have diverse opinions and views, and they adopt new things easily as a result. This view was confirmed by most of the interviewees who were not born in Seoul but live there now, who admitted that they have changed since they moved to Seoul to have a wider view of the world and to feel unrestricted when meeting diverse kinds of people.

3. Open-Mindedness and Friendliness

The third theme Seoul City tries to portray in reflecting community identity in the Hi! Seoul Festival is open-mindedness and friendliness. The symbolic building of the Hi! Seoul Festival in 2008 and 2009, “May Palace,” which was built on Seoul Square during the festival, symbolizes open-mindedness and the broad horizon of the festival in its design. According to the Seoul City Council, while traditional palaces are in the form of buildings whose spaces are confined by walls and doors, May Palace has no doors or walls, but a splendid roof and pillars created by light, so it is wide open to all visitors and citizens, providing them with space to be together and dance together (Hi Seoul Festival, 2012). This symbolic building represents the attitude of citizens of Seoul toward visitors.

Moreover, the brand name “Hi! Seoul” itself represents friendliness as the interviewee from the city marketing division of Seoul City Council remarked,

However, the interviews with local residents showed that they have different opinions regarding the friendliness of citizens. When they were asked how they think people of Seoul, they rarely mentioned the ‘friendliness’ of the citizens of Seoul. Among the five interviewees who mentioned related traits, three described the citizens of Seoul as indifferent and individualistic, and only two used the term “friendly” when they described the people in Seoul.

Among the three who described Seoul’s citizens as indifferent and individualist, one was raised in Seoul, while other two moved into Seoul from small towns after they became adults. One described the characteristic of “indifferent” in a positive way, stating that she can act and think freely since she does not need to care about what other people think. The other interviewee stated the terms “indifferent” and “individualistic” in a negative way in the context of comparing citizens of Seoul to people from his hometown. The two interviewees who described the people of Seoul as “friendly” moved into Seoul after they became adults, but the two who moved to Seoul as adults and described its citizens as “indifferent” moved to Seoul from small towns, while the two who described the citizens of Seoul as “friendly” moved to Seoul from other major cities in South Korea.

Although generalization may not be appropriate, this difference could imply that indifference and individualism are traits of people in big cities, so people from small towns see indifference in comparison to their smaller, more intimate hometowns while people from other big cities see friendliness in comparison to the people of others cities. Any firm conclusions on this speculation will requires more research.

In brief, it is not easy to conclude whether friendliness, one of the main images of the Hi! Seoul Festival, reflects the identity or characteristics of the city’s citizens. However, characteristics like friendliness are relative, so additional research may be required before it can be determined whether this characteristic describes Seoul’s citizens. As identities are often formed in one’s relationships with others and are influenced by how one is seen by others (Breakwell, 1986), and as community identity is influenced or strengthened by visitors (Getz 2007), additional research regarding visitors’ perceptions is needed.

4. Citizens’ Perceptions of Hi! Seoul Festival

One of the reasons that reflecting community identity in festivals is important is that doing so will encourage the communities involved to participate in the festivals by providing human resources (Getz, 2007) and contributing to the authenticity and unique atmosphere of the festivals through their active participation (Dredge & Jenkins, 2007). Therefore, it is essential to know how the community perceives the festival and whether they enjoy it.

The results of the twenty-one interviews showed the citizens’ perception of the Hi! Seoul Festival. Although most interviewees had heard of the festival, only 25% of them had participated. One of the interviewees said that what the festival is about is ‘not quite clear’, mentioning that the identity of the festival is ‘too vague’. A respondent who participated in the festival as a performer, stated:

This comment suggests that the effort to appeal to the diverse tastes of citizens can have an unintended result. According to Quinn (2005, p. 938), “The modern festival is a sort of supermarket where the paying public is persuaded to bulk-buy processed culture and. such events quickly start to look the same.” Therefore, careful consideration should be given to composing the content of the festival, even though it is for and intended to reflect the local community.

In addition to the festival’s vagueness of identity, the citizens of Seoul tend to think the festival is only for visitors. Half of the interviewees who had not been to the festival said that they feel that the festival is not for the residents, but for visitors, especially foreign visitors, and that the purpose of the festival is to create a good image of Seoul. Another interviewee pointed out the lack of opportunity for actual participation in the festival, saying that citizens are just spectators of the festival, not participants. This problem could be reflected in the theme of “international”; while the festival includes performances of artists from all over the world to meet the international and diverse cultural tastes of citizens of Seoul, it also causes the citizens to be alienated from participation in the festival. As Quinn (2005) stated, in festivals today, the local community tends to be spectators, not participants, and to remain side-lined.

However, as Quinn (2005) argued, the festival is a party and the community is the host, not a guest, so it cannot be a spectator but must participate. This participation by the local community is a primary attraction for cultural tourists; it adds a unique atmosphere to the festival and the destination (Getz, 2007), which is one of the aims of the festival as a way to achieve destination branding. To induce more participation by the citizens in the festival, Seoul City Council tries to reflect the general community’s identity in the festival, but they must also consider the citizens’ perception of the festival and how they want to participate in it if the council wants to achieve the festival’s purpose. In sum, a diagram developed to reflect the findings of this study is presented as Figure. 1.

This study was undertaken in the context of a rise in the practice of employing festivals as a way of destination branding. However, many festivals organised for destination branding have not yielded optimal returns (Quinn, 2005). Destination branding is more effective if it reflects the community identity, as doing so contributes to the genuineness and sustainability of the festival. In regard to the Hi! Seoul Festival, three key themes were identified: cohesiveness, culturally international and diverse, and open-mindedness and friendliness. In identifying these themes, the Seoul City Council reflects the community identity considerably well in terms of brand identity.

The Hi! Seoul Festival has a shortcoming in that it did not originated from the community but was strategically created by the Seoul City Council for the purpose of boosting Seoul’s image as a tourist destination. The Seoul City Council looked for justification for the festival by placing its origin in a significant event for the citizens of Seoul and emphasizing the attendant image of cohesiveness.

While it is difficult to identify the common characteristics, thoughts, or tastes of citizens, as is often the case in a large, globalized city, Seoul City Council avoided selecting one or two major aspects of the city in favour of trying to include multiple aspects of the city to meet the diverse tastes of its residents. The result of this lack of a unified theme is the citizens’ muddled perception of the content of the festival and a festival that is lacking uniqueness and character. In order to reflect the community’s identity in the image of a festival, careful consideration to how to reflect the community’s identity in the festival is necessary, as merely reflecting the diverse inclinations of the community could have an adverse effect on citizens’ perception of the festival. Although they consider general fondness of citizens, they seem to fail to notice the fondness of citizens “in festival”. That is, when reflecting community identity in festivals as a means of destination branding, it is essential to find a way to reflect the tastes of the citizens as one, without including so many aspects of that identity that the festival becomes just a ‘collection of everything’ with no uniqueness. This mistake could prevent people from seeing the festival’s content as unique and authentic, which is important in inducing local people to participate and cultural tourists to attend.

Planning for the festival’s content and programs should distinguish between what the community generally likes and what the community wants to do in the festival that makes it a celebration. Although some parts of festivals feature volunteers and performers from the community, it is also the general populace from the place that spices the unique atmosphere of the festival and creates the image of the destination. The local population is not a guest of the festival, but the host to visitors. Therefore, programs that require the active participation of local citizens, rather than making them spectators, should be emphasized. In addition, since reflecting the community identity in the brand is critical if the festival is to have a good relationship with the local community, get their support, and have authenticity, the festival should originate from the community, rather than being created strategically from the outside. Outside organizers’ attempts to guess the community’s values does not guarantee the participation of the community unless they know it is based on their actual values.

However, even when the festival includes the community’s values and reflects its tastes, if the local community does not understand and contribute to the festival’s content, it loses its main purpose of branding the destination. As seen in the case of the Hi! Seoul Festival, although the Seoul City Council runs a website that explains the content of the festival, local citizens who do not visit the website will remain uninformed. Therefore, exposing the content of the festival as much as possible through many media, not just a single website, is essential. In the same vein, it is important to understand the behavior pattern of the daily lives of local residents and what influences them most if marketing is to be effective marketing. Previous researches regarding Hi! Seoul festival also argued that effective marketing is important for active participation of citizens (Shin & Sohn, 2005) as well as for satisfaction of participants (Jung, Yoon, & Lee, 2012).

The study has a few limitations that should be considered. Firstly, the findings of this study are confined to the Hi! Seoul Festival. Additional case studies of other festivals in other regions are needed before a deep understanding of how identities and destination branding using festivals is achieved. The second limitation relates to the study’s methodology. Narrative analysis, especially for exploring identities, requires having background information about the participants, such as information about the people, environment, and society around them, in order to understand fully the meaning of their stories. Such deep background requires a longer time than was available for this study and probably several interviews with the same participants (Riesman, 1993; Crossely, 2007). Future research that adopts narrative analysis may find it more effective to supplement with other research methods, such as participant observation and content analysis. In addition to brochures and guidebooks, the use of newspapers and other materials would help the researcher to understand the society in order to understand its identity.