INTRODUCTION: THE PROLIFERATION OF IRREGULAR WORKERS AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF A NEW LABOR MOVEMENT

While the policy of deregulation of labor markets has been pursued with the development of globalization since the 1990s, the irregularization of labor and the polarization of society have been progressing rapidly in countries all over the world, including Korea and Japan. What the proliferation of irregular workers means, both in Korea and Japan, is summarized in the following two points.

Firstly, it means that a lot of informal workers, whose employment and means of livelihood is precarious, have been produced. Most of the irregular workers cannot stay and work stably in a fixed workplace or firm, and so cannot earn a stable income. As a result of not having a fixed workplace or firm as a regular worker does, most come to be excluded from the protection of labor laws, social welfare and trade unions. The lack of social welfare happens because both in the Korean and Japanese social security systems, social insurance and company-paid benefits are overwhelmingly important. Moreover, while trade unions in the West are industrial unions, both in Korea and Japan the base of trade unionism is the enterprise union. Thus, the irregular workers, who lack the same protections of the regular workers, are forced to work under bad conditions with long working hours at low wages.

Secondly, the proliferation of irregular workers has caused fragmentization of labor and the isolation of workers. As the irregular workers in unstable employment, who have various and diverse interests, have increased rapidly, it has become more difficult to build “the labor society,” which is a kind of visible community where the members experience a common occupational life and have a similar experience in terms of the length of employment at one workplace, and therefore share common needs, interests and possibilities in their lives based on these commonalities (Kumazawa 2013: 31). In “the labor society,” practices of cooperation and protecting each other are spontaneously generated. It is through “the labor society” that the trade union is consciously organized, and through the policy of the trade union that the practices of “the labor society” are regularized (Kumazawa 2013: 26). As a result, the traditional enterprise-based trade unions, centered on the common workplace or firm, have found it difficult to organize workers, and so have rapidly become weakened and come to lose their leverage in society. Therefore, we need to find a way to form a new “labor society” composed of the irregular workers who have lost stable workplaces and communities where they could settle and were thus isolated, and learn how to unionize them into a new model of trade union which is suitable to the characteristics of the new “labor society.”

Thus, as the influence of the traditional enterprise-based trade unionism, mainly composed of male regular workers in the large enterprise, has diminished in society, both in Korea and Japan, since the latter half of the 1990s, new labor movements and labor movement theories have emerged, which have tried to organize mobile, fragmentized and isolated irregular workers. Specifically in Japan, the movements of the community unions represented by the individually-affiliated unions have come to attract attention (Ito 2013; Kinoshita 2012; Kotani 2013), and the trend of new labor movements and labor movement theories such as social movement unionism have been introduced (Suzuki 2012a; Suzuki 2012b; Yamada 2014). However, while in most of these studies, the focus of discussion is mainly on the strategies and tactics and the purposes of the labor movements and how they organized irregular workers, the common characteristics of the employments and the ways of behavior, thinking and living of the workers are not well clarified. But, without considering their common characteristics, which bond the workers together, we cannot know how the labor society, which is the foundation of the trade union, should be formed.

And so, in this paper, first I will explain both the characteristics and the actual state of the irregular workers in Korea in the same way as I historically and structurally examined the meaning of irregularization of labor in Korea, focusing on the comparison between regular workers and irregular workers (Yokota 2012). After that, I will discuss how the irregular workers have been organized in Korea, in particular taking the case of the Korean Women’s Trade Union (KWTU) since the economic crisis of 1998 when the problem of irregular workers became a serious issue of public concern.

The reason why I specifically studied organizing female irregular workers is that the main features of the irregular workers in Korea appear to be exceptionally strong among them, and furthermore their employments are conspicuously informal and marginalized, which I describe later. Faced with this reality, the KWTU has tried to organize female irregular workers and has developed its unique movements, which were different from the traditional labor movements. Accordingly, I aim to specify this attempt by the KWTU as a new and unique pattern of organization and movement of irregular workers. Moreover, when we consider how the working people in Japan could revitalize the labor movement, valuable suggestions for a new model of trade union can be taken from the organization of female irregular workers by the KWTU in Korea. Such revitalization is necessary because, hitherto, traditional enterprise unions, mainly composed of male regular workers both in Korea and Japan, have rapidly and simultaneously become weakened with the proliferation of irregular workers due to globalization, especially since the 1990s.

We can take Chun (2009) as a representative and excellent study on the comparison of female irregular workers’ union struggles in Korea and the United States. However, it didn’t examine the female irregular workers’ attributes or characteristics in detail, although their analysis is indispensable for considering how “the labor society” is formed, which in turn, determines how the trade union is organized. Therefore, in this paper I will examine the process of creating “the labor society” or the trade union of female irregular workers by the KWTU.

Moreover, I will indicate the issue facing the KWTU and the limitation of organizing female irregular workers, and in place of a conclusion, I will show that the KWTU could overcome these conditions through cooperation with the Korean Women Workers Association (KWWA), which is a female labor organization established in 1987 and the founding mother of the KWTU. The approaches to solving these problems are highlighted as a new and unique pattern of organization and movement of irregular workers.

THE CHARACTERISTICS OF THE IRREGULARIZATION OF LABOR IN KOREA

The Economically Active Population Survey has been carried out by the Korean government since 1963, and the Supplementary Survey on Economically Active Population has been done since 2001 to estimate the number and working conditions of irregular workers in Korea. However, the official statistics by the Korean government have underestimated the number of irregular workers in Korea that account for about 35% of total wageworkers in the 2000s, because they have eliminated the temporary workers from the category of irregular workers as they have apparently been under employment contracts of an indefinite duration. But, in fact, they have been put under precarious employment conditions that are similar to official irregular workers’ (Yokota 2012: 178-182); . Therefore, this paper takes the estimation method of the Korean Contingent Workers’ Center which considers temporary workers as irregular workers.

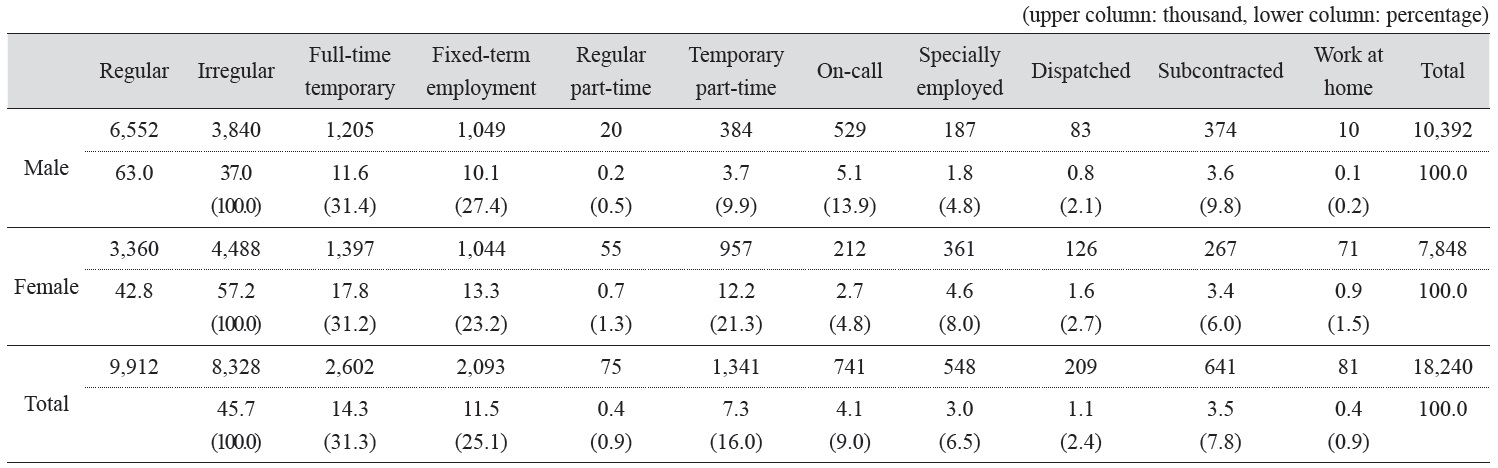

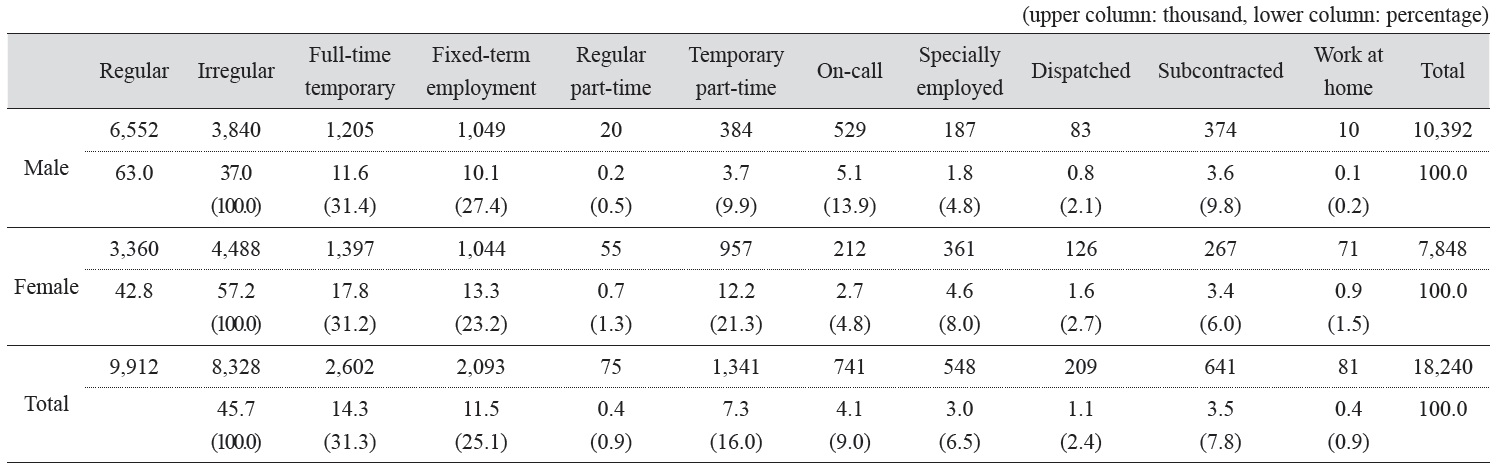

According to the estimation of the number of irregular workers in 2013 by the Korean Contingent Workers’ Center (Table 1), we can find that irregular workers account for 45.7%, which is close to half of all wage earners in Korea. However, female irregular workers make up 57.2% of all female wage earners while male regular workers comprise 63.0% of all male wage earners. This fact indicates that the irregularization of female workers has remarkably developed compared with male workers since the 1990s in Korea.

[Table 1.] Employment Structure in Korea (2013)

Employment Structure in Korea (2013)

Moreover, as Table 1 shows, full-time temporary workers account for 31.3% of both female and male irregular workers, and combined with the group of part-time temporary workers (16.0%), temporary workers clearly represent the largest group of irregular workers in Korea. In addition to this, by gender, the percentage of all female and male temporary workers, which include part-time temporary workers as well as full-time temporary workers, of irregular workers, is 52.5% and 41.3%, respectively. Especially, female temporary workers comprise the overwhelmingly majority of the irregular workers. Accordingly, while the portion of temporary workers of all male wageworkers is 15.3%, the percentage of temporary workers of all female wageworkers is 40.0%, and which is about 25 points higher than that of all male wageworkers. That means that two out of five female wageworkers are temporary workers. Thus, we can definitely find gender differentials in the category of temporary workers.

The most noteworthy characteristics of the majority of “temporary workers” in Korea1 is that, unlike advanced countries where employment of indefinite duration means stable employment for a long time, in Korea, even if their employment’s duration is not indefinite, they are never guaranteed to be able to continue to stably work at their workplace for a long term into the future (Yokota 2012: 183-185). More specifically, many of them are concentrated in precarious firms employing fewer than 5 workers (female 49.3%, male 36.4%), and particularly, about the half of female full-time temporary workers are remarkably concentrated in small precarious firms (National Statistical Office 2013). As will be discussed in detail below, their working conditions of low-wages and long working hours is remarkable among the categories of irregular workers, and especially the working conditions of female temporary workers is worse than male temporary workers. As stated above, we can find gender differentials between female and male temporary workers who experience much more precarious employment than other categories of irregular workers in Korea.

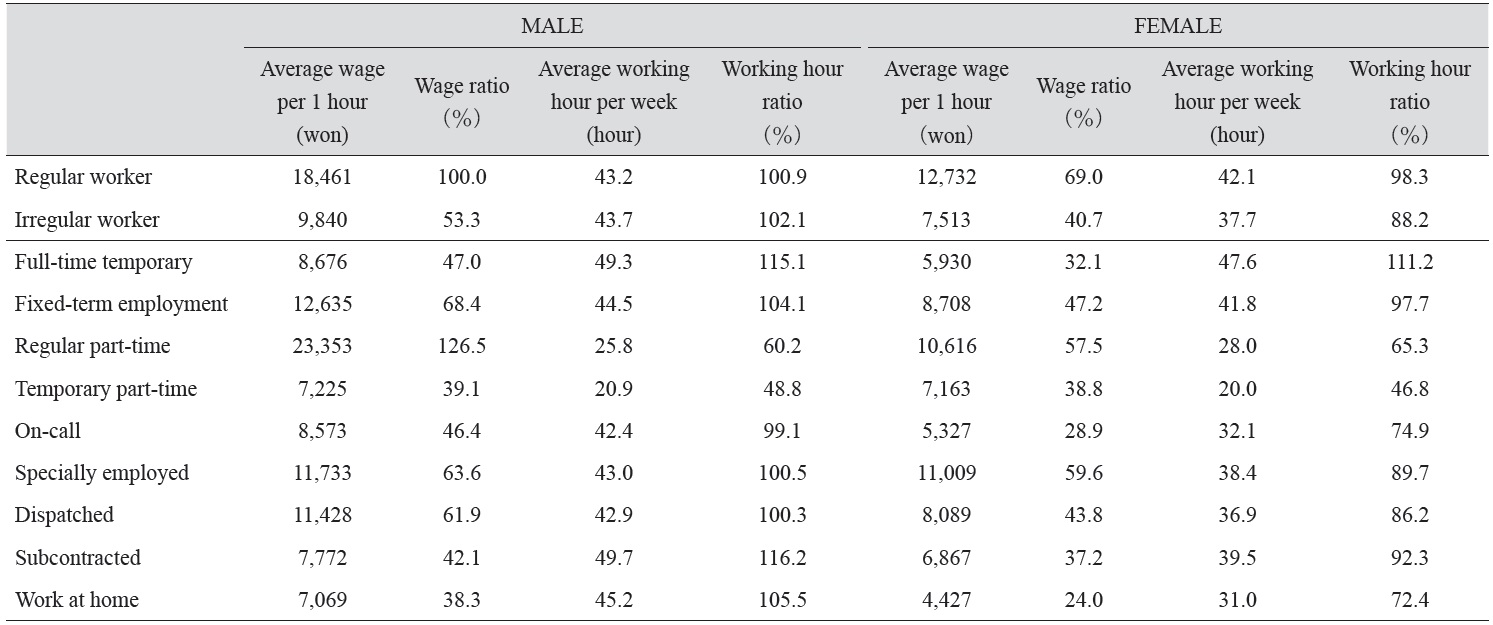

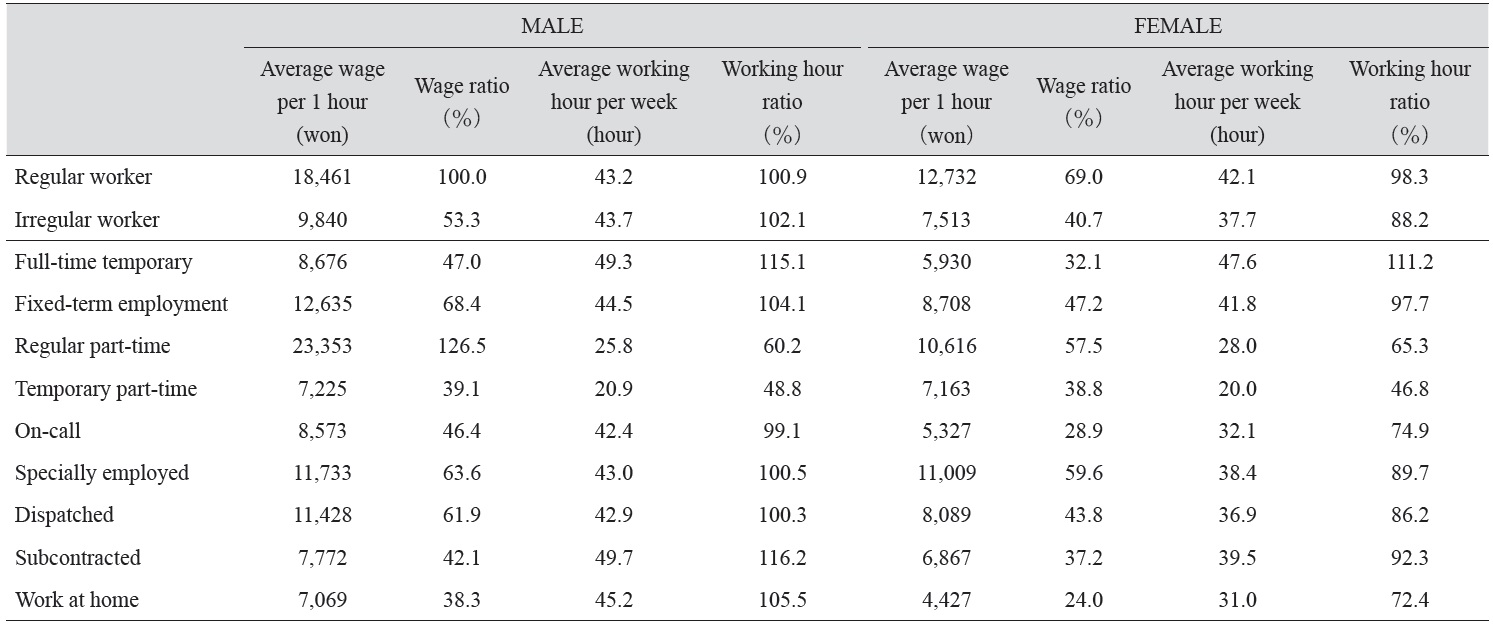

While irregular workers work under notably bad working conditions of lower wages and longer working hours compared with regular workers in Korea, we can also find gender differentials between male and female irregular workers. As Table 2 shows, the average wages of female and male irregular workers are 40.7% and 53.3%, respectively, that of the wage of male regular workers. Additionally, the wage level of female irregular workers is 12.6 points lower than that of male irregular workers. Furthermore, the average wages of female and male full-time temporary workers, who constitute the largest group among the irregular worker’s categories, are 32.1% and 47.0% of male regular workers’ wages respectively, which is about 8.6 and 6.8 points less than the average of female and male irregular workers, respectively. On the other hand, while the average working hours per week of male regular workers is 43.2 hours, that of male irregular workers is 46.3 hours and that of female irregular workers is 42.8 hours. But, the average working hours per week of full-time temporary workers become longer than that of irregular workers; female full-time temporary workers average 47.6 hours per week, compared with that of male temporary workers at 49.3 hours per week. This is a remarkable difference.

Average Wage per Hour and Average Working Hour per Week by Employment Status and Gender in Korea (2013)

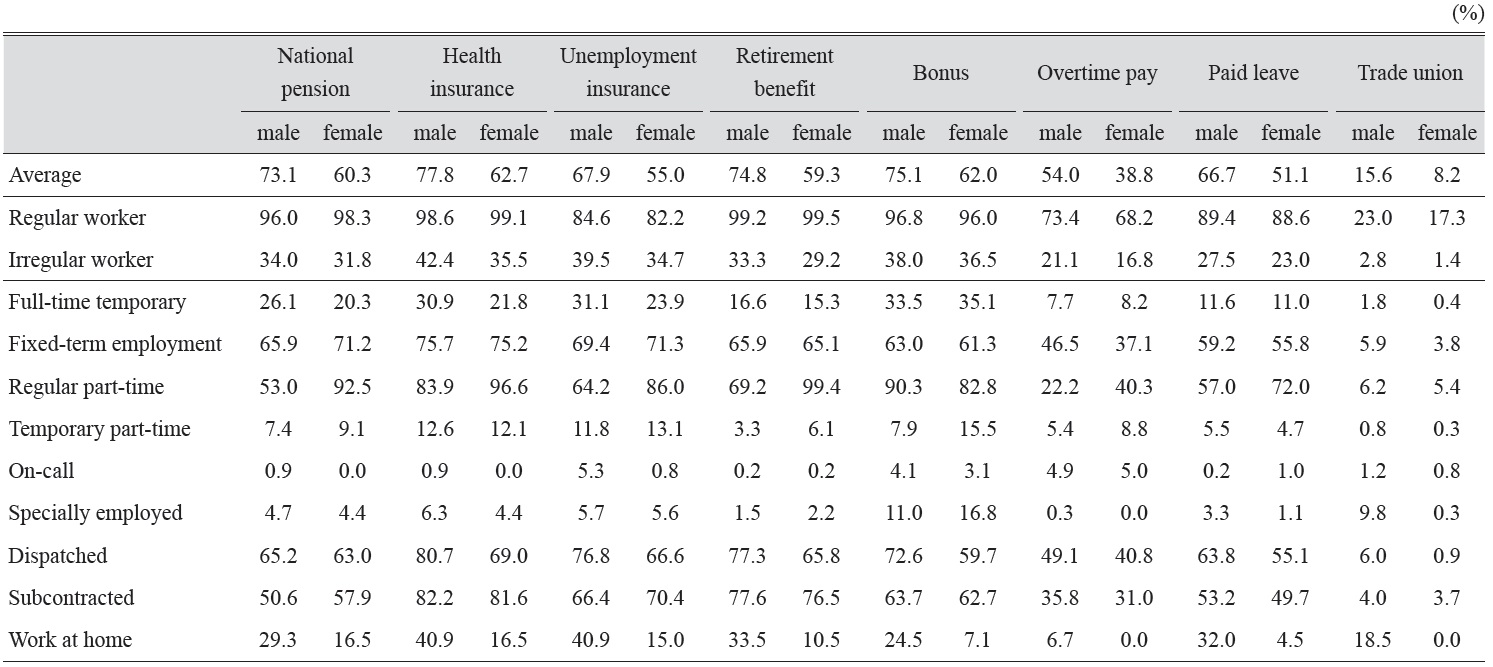

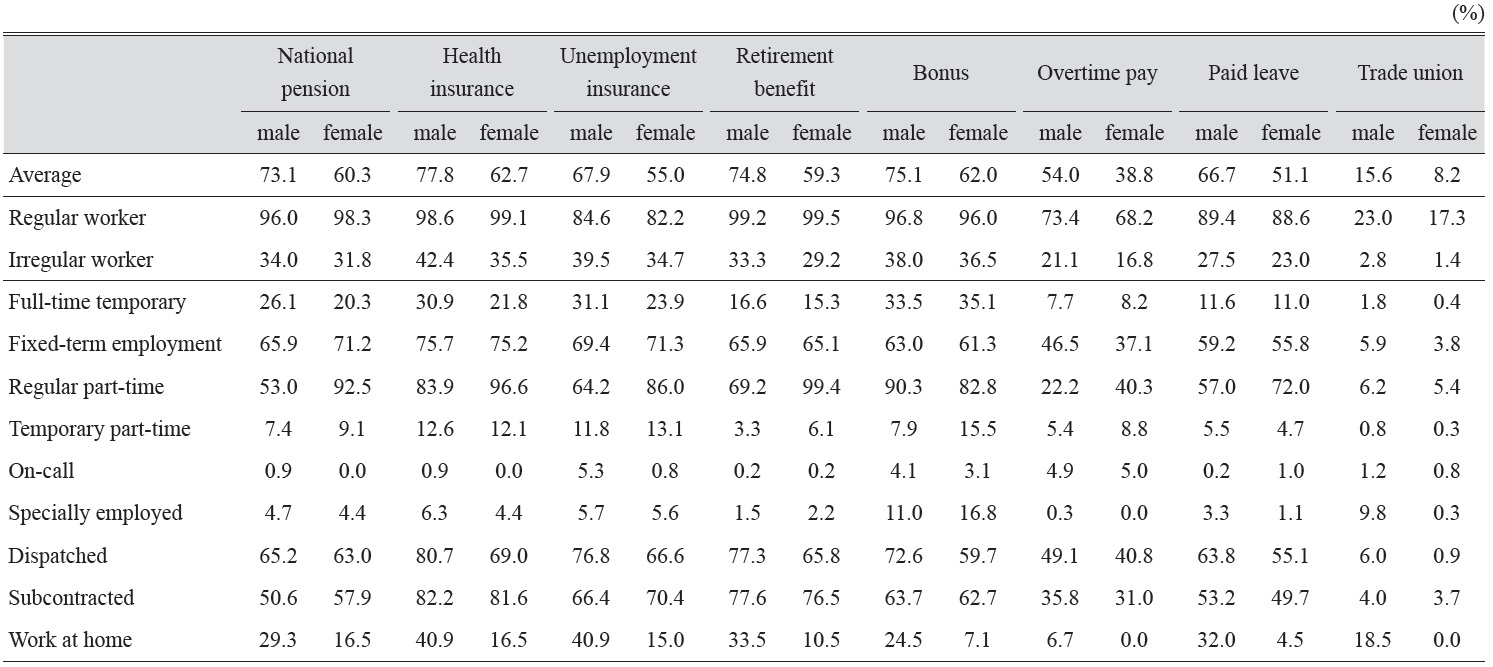

Moreover, as Table 3 shows, we can recognize that between sixty to seventy percent of all irregular workers are excluded from company-paid benefits and the social welfare system by the government, while most regular workers are included in them. Further, obviously, gender differentials exist between male and female irregular workers, as well.

Coverage of the Social Security System and the Fringe Benefit and Percentage of Union Members by Employment Status and Gender (2013)

Similarly, we can see that the percentage of trade union members in irregular employment is remarkably lower, and it is especially true of female irregular workers who comprise the lowest group in Table 3. That is to say, the percentage of trade union members who are male irregular workers is 2.8% and that of female irregular workers is only 1.4%, while that of male and female regular workers is 23.0% and 17.3%, respectively. More specifically, there is an extremely low rate of just 0.9% of trade union members who are female temporary workers.

Additionally, while the average length of continuous employment of regular workers is 8.27 years, that of irregular workers was no more than 2.28 years in 2012 (National Statistical Office 2012). This fact indicates that the employee retention rate of irregular workers is overwhelmingly low.

Lastly, the proportion of irregular employees at a small business, where the number of employees is fewer than 5 workers, is 32.8% and that is nearly four times the rate of 7.6% of regular employees in 2013. Of special note, the proportion of female irregular employees at small businesses is 36.7% and a good 8.6 points higher than the 28.1% of male irregular employees (National Statistical Office 2013). As mentioned above, the rate of temporary workers who are employed at a small business is strikingly high. What does this mean? This means that the workers who work at these extremely small businesses where fewer than five workers are employed not only can hardly be unionized because they are scattered and isolated, but also are hardly protected by employment security because restrictions on dismissal of workers and clear indications of working conditions provided by the Labor Standards Act are not applied to them. Accordingly, they cannot stay stably in a fixed workplace or firm, and so, change their jobs frequently.

In addition to these irregular workers under direct employment by a company, I have to point out that there are massive numbers of employees without direct employment relations, such as “dispatched workers” or “contract-based workers”, and moreover, independent contractors commonly referred to as “specially employed” workers that constitute a noteworthy characteristic of irregular employment in Korea.

Although the labor law in Korea had prohibited indirect employment since 1953, when the Labor Standards Act was enacted, the establishment of the Temporary Agency Worker Protection Act in July 1998, which was instituted in the wake of the economic crisis of 1997, overturned “the principle of direct employment.” After that, indirect employment, such as dispatched workers or contract-based workers has occurred, and more especially, they have rapidly increased since the Nonstandard Employment Act, which limited the employment period of fixed-term workers to a maximum of two years, was carried into effect in July, 2007 (Lee 2014: 2).2

However, it is most worthwhile to note that independent contractors commonly referred to as “specially employed” workers exist in Korea in large numbers. Most of them are classified as “the independent self-employed” and are excluded from legal recognition as workers, although they work, in fact, as workers dependent on employers and firms. Therefore they not only are excluded from the protection of all kinds of labor laws including the Labor Standards Act, but they also cannot organize their own trade union to negotiate their collective working conditions. While “specially employed” workers are steadily increasing in a broad variety of jobs, many of them are not able to be counted in official government statistics3 because of their informal characteristics, and overlap considerably with the traditional urban informal sector (Yokota 2012: 189). Typical examples of these kinds of workers can be found as golf game assistants (caddies), insurance salespersons, wholesale and retail salespersons, home-based tutors for elementary school students, animators, telemarketing operators, home-delivery agents, ready-mixed concrete and dump truck drivers, bill collectors, care workers, home care workers, etc.

So, we can summarize the characteristics of irregular workers in Korea as follows:

1It is the temporary workers that have the most precarious employment of irregular workers in Korea. Even though precariousness of employment is characteristics of all irregular workers, temporary workers have it worse. 2Although the proportion of dispatched workers or contract-based workers of all wage workers is respectively 1.1% and 3.5%, while not so high statistically, many of the workers employed by a temporary agency or contract company are likely to be counted as regular workers by the Supplementary Survey on Economically Active Population (Yokota 2012: 188). 3According to the estimation of “specially employed” workers by the Korean Contingent Workers’ Center, in fact, just the number of home-delivery agents among the various categories of the specially employed approximates to the entire number of “specially employed” workers shown by the official government’s statistics (Korean Contingent Workers’; Center 2011: 3).

THE ACTIVITIES OF THE KOREAN WOMEN’S TRADE UNION FOR ORGANIZING FEMALE IRREGULAR WORKERS

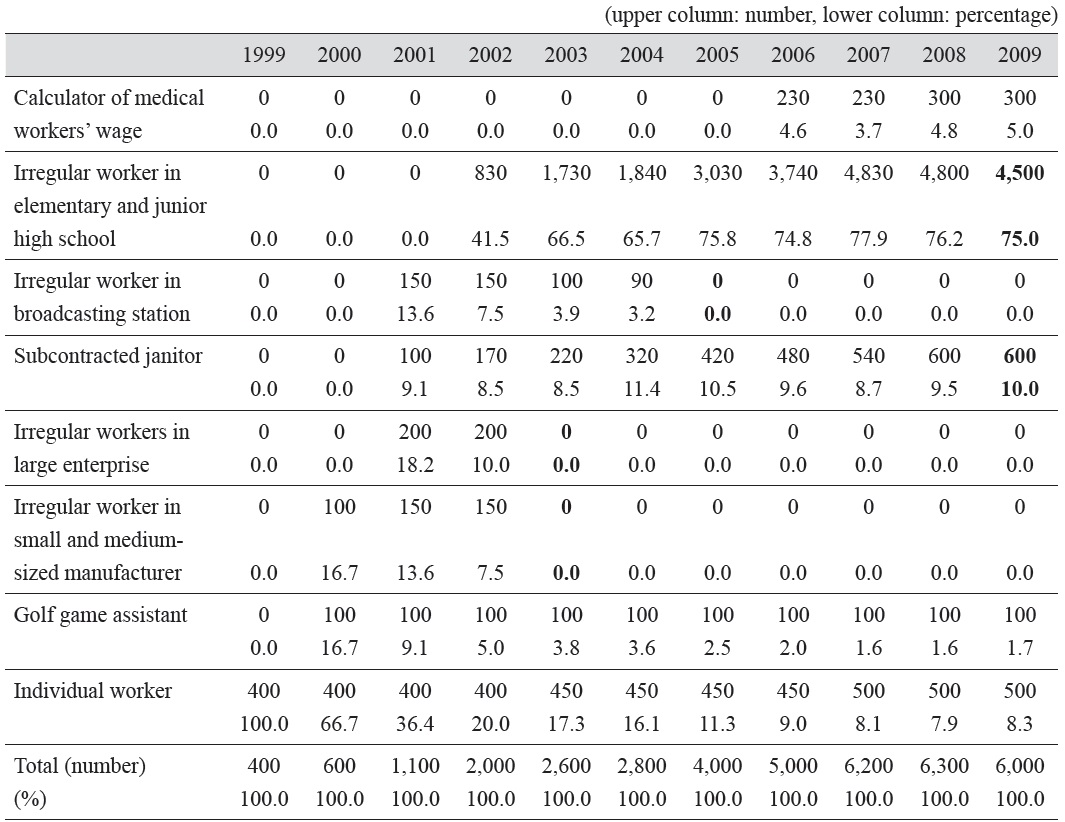

The Korean Women’s Trade Union (KWTU) was established in August of 1999, aiming at organizing unorganized female workers, especially female irregular workers who have the most noteworthy characteristics of the irregular workers in Korea, as mentioned above, and acquiring their right to labor. The number of the union members has increased steadily from 400 in 1999 to over 6000 as of 2009 and has developed into an organization that has 10 local branches and 70 sub-branches (KWTU 2009c: 139-140).

>

How Has the KWTU Organized Female Irregular Workers?

The Background of the Establishment of the KWTU

The Korean government introduced the radical deregulation policy of the labor market, such as legislation for dismissal due to economic conditions and the Temporary Agency Worker Protection Act, in order to deal with the economic crisis in 1998. As a result, first of all, female workers were dismissed prior to the dismissal of male workers and were replaced by irregular workers, and so a lot of female irregular workers were produced. Accordingly, the organization of a women’s union was immediately needed in order to protect their labor rights, because female irregular workers have always been excluded from the mainstream labor movement, which has been male-dominant enterprise unionism (KWTU and KWWA 2001: 8-9). Therefore, the Korean Women Workers Association, which was established as a female labor organization in 1987 in order to improve the political, economic and social status of women, created the Korean Women’s Trade Union sending half of its members there in 1999 (Working Woman Education Network 2006: 5; Jin 2007: 184).

In addition to that, we have to state the transition of the industrial relations legal system as the background that enabled the establishment of the KWTU. As a result of “the great workers struggle” in 1987, the laws written under the authoritarian regime, before the democratization, specifying that only the enterprise unions were permitted as a trade union were elided from the Labor Union Act, and so the organization of the community union and the general union, as well as the industrial union were legalized. The community unions or the general unions whose basis of organization is on a regional scale and the whole country beyond the enterprise, like the KWTU, are most suitable for organizing unstable and insecure workers who change or lose their jobs frequently and move from place to place.

The Features of the Organization of the KWTU

The KWTU has been an independent and general woman’s trade union, which any working woman can join by herself without distinction of industry, occupation, or region, or whether she is unemployed or not beyond the enterprise. Because female irregular workers in Korea frequently change their jobs and regions where they live and work, they could maintain their qualification for being a member of a single, nationwide trade union through this organization. As a result, female irregular workers came to hold 99% of the membership of the KWTU(KWTU 2009c: 140-141).

The KWTU has been free and independent from the policy and line of both national centers of the Korean Confederation of Trade Union and the Federation of Korean Trade Unions because it intentionally did not come under either national center of trade unions at first (Jin 2007: 189-190). This is probably because the voice and demands of female workers have hardly been reflected in the policies or activities of the existing trade unions, which have been male-dominant and centered on male regular workers, including both national centers and local unions under their umbrella (Choi 2006: 115).

Accordingly, the KWTU aimed for the organization that has a strong affinity for women from the very start (Park and Kim 2001: 121). That is to say that the KWTU aimed to form “the labor society” focused on the members being female irregular workers.

Every local branch of KWTU has sub-branches referred to as “Bunhoe” and sub-chapters referred to as “Jihoe.” While the “Bunhoes” are organized based on the members working in the same workplace, the “Jihoes” organize the union members who are scattered and isolated at each workplace, by the type of occupation or industry (KWTU 2009a: 25-26; KWTU 2009b: 20). Although the KWTU tried to organize female irregular workers focusing on the “Bunhoes” at the beginning, it has recently been devoted to organizing the “Jihoes” that are more difficult to organize (KWTU 2009a: 28; KWTU 2009b: 55-56), because it has aimed to make occupation or industry, as well as workplace and region, a common feature as the pivot for the solidarity and stability of female irregular workers in order to overcome the difficulty in organizing them caused by their dispersion.

The fundamental constituents of the organization of the KWTU are small groups. And so, activities of small groups are characteristics of the KWTU. Small groups are formed by occupation, workplace, hobby, belonging to another sub-group like a female breadwinner of a single-parent family, or married or unmarried woman, and so on. The union members always belong to some small groups and act together not only in union activities, but also in hobbies, cultural activities and daily living. Thus, female irregular workers who are isolated and scattered, moving frequently in unstable employment are connected closely through activities of small groups where they come to have direct and daily relations with one another. As a result of this, the channels of horizontal and mutual communication between the union members are opened. Additionally, through their participation in the activities of small groups, they can foster and establish their identity as an immediately interested party and their responsibility to the union (Park and Kim 2001:121-122).

Based on this organizational structure, the KWTU tried to intentionally have a bottom-up decision-making system and a democratic management of the organization in contrast to a topdown decision-making system of the traditional and male-oriented trade union, and succeeded in doing this. Concretely, representatives of every “Bunhoe,” “Jihoe” and small group, gather and decide the policy of the local branch in their steering committee meeting held once a month. Moreover, the central executive committee is held once a month in the headquarters of the KWTU where the managers of every local branch, elected in every region and the executives of the headquarters decide and implement the plan of activities of the KWTU(KWTU 2001: 38; KWTU 2009b: 20).

Interestingly, unlike the existing trade unions, the KWTU has tried to remove the boundary between the public and private fields of the union members. For example, as can be seen in the educational program for the union members called “program for self-discovery and selfrelease,” they come to be able to have a sense of coessentiality with one another through looking back to and talking about their own lives as a woman, together with colleagues of thetrade union. Especially, the union members have tried to share and resolve domestic problems, such as childcare, that have traditionally been considered as personal and private problems, together in the public field of the trade union (Park and Kim 2001:122-123). Thus the KWTU has aimed to create a new “labor society” by fostering and sharing a strong sense of camaraderie and cooperation with coessentiality among the union members.

>

The Development of Movement of the KWTU

Remember, most of the female irregular workers work at small businesses and are scattered and isolated in Korea. Accordingly, if the KWTU mainly depended on traditional methods such as collective bargaining limited to every business and workplace, their leverage necessarilywould be too weak to change the harsh reality they faced. In order to overcome their leverage limitations, the KWTU used two strategies. That is to say, it tried to render the problems of female irregular workers into issues of public concern, and aimed to expand the organization of the female irregular workers through the first strategy.

As shown in the following, the KWTU has raised the problems of female irregular workers as serious public issues and succeeded in involving public opinion in them using various means, and so gradually achieved the improvement of their conditions of employment and working.

Firstly, we can mention that the KWTU emphasized labor counseling as a means of accomplishing this.

The KWTU expanded an individual labor-related dispute, which was grasped through labor counseling, into collective issues in the whole workplace and, moreover, into the issue of public concern as a common problem that all the workers in the same industry shared. Backed by the social development of the issues, the KWTU has gradually achieved the improvement of working conditions through collective bargaining and the further expansion of its organization.

For example, when the KWTU was consulted by the cooks of school meals concerning bad working conditions and discriminatory treatment, it found the occasion to pose bad working conditions and discriminatory treatment of the irregular workers who work at elementary and junior high schools, which are in the public sector, as the issues of public concern in 2002. After that, the KWTU has succeeded in expanding its organization based on the irregular workers at elementary and junior high schools (KWTU 2009c: 147).

Secondarily, the KWTU implemented the detailed and objective research on the actual conditions of female irregular workers in cooperation with experts and researchers and being based on the findings, held open forums and social meetings. In addition to this, it appealed to the public using various ways such as a rally, a demonstration and a sit-down strike, and so on(KWTU 2009b: 25). It is worthy of special mention that the labor activists have had a close and cooperative relationship with experts and researchers in academia or the pro-labor research institutes in Korea, because many of them together took part in democratization or labor movements as university students against the authoritarian regime in the 1980s.

Thirdly, the KWTU has often advanced the struggle against the government for labor law reform and establishing new labor laws by appealing to the public about the problem of female irregular workers, because it is difficult to conduct collective bargaining with a company for the female irregular workers in Korea with the characteristics discussed above. The struggle of golf game assistants at the 88 Country Club, and the struggle of subcontracted university janitors in Inchon and Seoul are regarded as representative cases of the struggle for labor law reform by the KWTU.

In the former case, in 2000 the 88 Country Club sub-branch of the KWTU, which consisted of the golf game assistants who were “specially employed” workers as independent contractors and were exempted from the application of all of the labor laws including the Labor Standards Act and faced gender-discriminative treatment by the employers, struggled for recognition by the government as workers. As a result, labor laws came to be applied to them, and thus a group of “specially employed” workers were legally recognized as workers (KWTU 2009b: 30-32).

In the latter case, the subcontracted university janitors in Inchon and Seoul rose up for improvement of their working conditions, whose wages remained at the level of the minimum wage in 2001, which was only about $400 per month. Thus, appealing to the public on grounds of social justice, the KWTU was the first to develop a movement for the reform of the minimum wage system, before other labor organizations began to do so. This continuously increased the minimum wage up about $950 per month in 2010, and led the KWTU to increase the organization of the subcontracted university janitors even more (KWTU 2009b: 33-35).

Fourthly, the KWTU has worked in cooperation with various social movement organizations such as women’s groups, citizens’ groups, student movement groups, labor organizations including both the national centers of trade unions and the trade unions of regular workers, and so on (Jin 2007: 187-88; KWTU 2009b: 34). When an employer committed an offense that was against the law, the KWTU even demanded the intervention of the government, such as the Ministry of Labor, on some occasions, something that existing labor trade unions have avoided as government interference in autonomous industrial relations. In any case, the KWTU has positively increased the struggle for labor law reform together with other social movement organizations, not only for the reform of the minimum wage system, but also for the guarantee of the basic legal rights of female irregular workers in triangulated employment, such as a temporary agency employee, in 2008 (KWTU 2009b: 35-36).

From the above discussion, it seems that the KWTU has successfully organized female irregular workers in Korea for more than ten years. However, a serious problem with organizing these women by the KWTU has also been revealed at the same time.

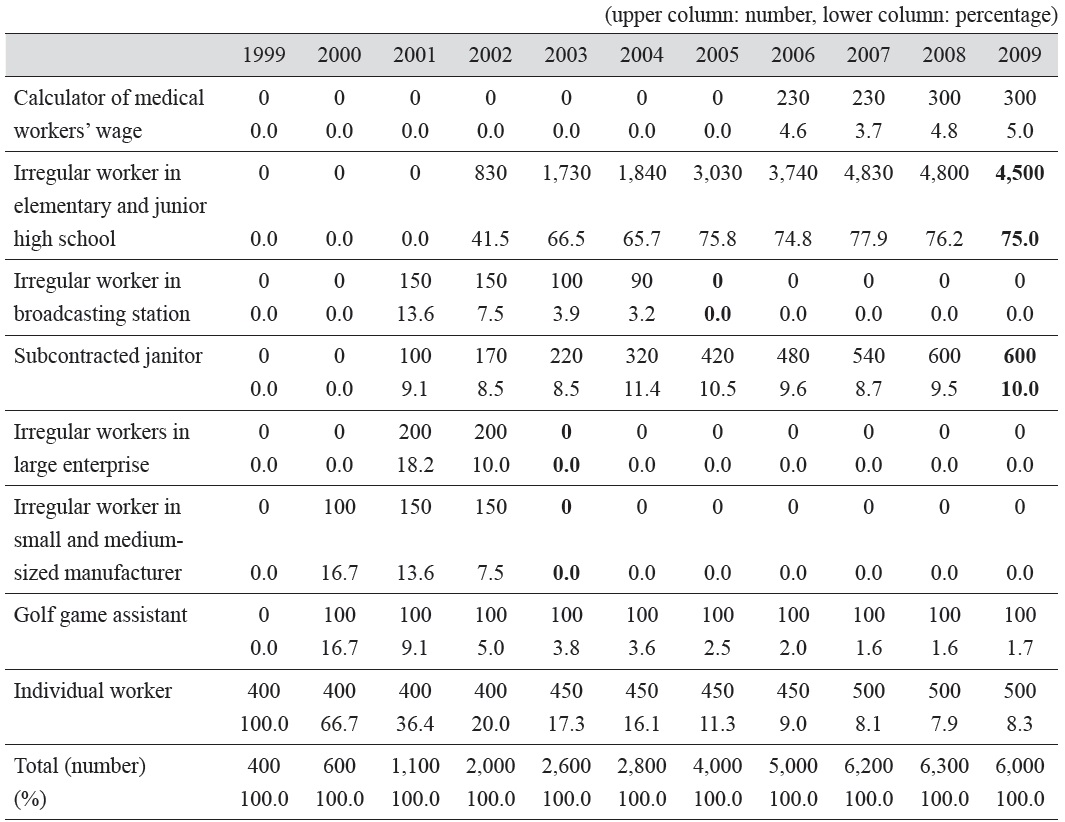

As Table 4 shows, the membership of the KWTU tends to be concentrated on relatively stable or non-isolated irregular workers after 2003. That is to say that they are concentrated on irregular workers who work at elementary and junior high schools and whose employments are relatively stable because of their relatively high education and certifications and that their jobs are in the public sector, or subcontracted janitors and golf game assistants who can work collectively at a common workplace.

[Table 4.] The Numbers and Distribution of Union Members of KWTU

The Numbers and Distribution of Union Members of KWTU

However, as seen before, the majority of female irregular workers in Korea are so informal, so unstably employed and separately scattered that it is very difficult to organize them. For example, they are female irregular workers without high education or skills who work at small restaurants, small retail stores, a small factory in town and small family run shops, and so on. Although the KWTU aimed to organize the female irregular workers such as these from the beginning, it was confronted with the practical difficulty of organizing them, and so it seems to have abandoned the effort to do that for now. That’s exactly the point where the issue and limitation of the KWTU lies.

In the next section, in place of a conclusion, I will show a new model of trade union that I propose could overcome this limitation and resolve the issue of the KWTU.

As mentioned above, since 2003 the KWTU has come to increasingly organize more stable and cohesive irregular workers who work at the same workplace or in the same occupation. In other words, the KWTU has come to prefer to organize the irregular workers who can more easily form collective labor-management relations. That change may be necessary in so far as the KWTU is a trade union that naturally has to form collective bargaining relations.

However, what is characteristic of the female irregular workers in Korea is that they are working under unstable and mobile employment, as well as experiencing a non-cohesive and dispersive existence. Therefore, under unstable employment conditions many of them have experienced repeated turnovers and unemployment, which causes their social instability and low income. In spite of this fact, they are put into a blind spot of the social security system. To start with, because they are not recognized as workers, they are exempted from the application of labor laws and are thus not protected by labor laws. So, how can they be organized into a “labor society”?

To parse this problem from the final effect mentioned above, it is impossible to organize the female irregular workers with the particular set of characteristics noted above through the system of the “trade union,” which has limitations that prevent it from protecting workers who could not form labor-management relations. In order to overcome this difficulty, in 2004 the KWWA, which created the KWTU, established the National House Manager’s Cooperative with the intent to organize home care workers who are typical of the majority of informal female irregular workers that are excluded from labor laws, the social security system and the protection of labor trade unions. It is a cooperative society that strives for the economic selfreliance of female irregular workers who have low-education and are in their 40s and 50s and older. It aims to create jobs for home care workers, protect their rights as workers and give them education and training. It had 11 branches and over 700 members all over the country in 2009 (KWWA 2009: 42).

Concretely, the House Manager’s Cooperative is a cooperative society for which every member pays a monthly membership fee of about $30, and which all the members manage autonomously by themselves, unlike the private agents that take a commission from customers (in this case, the workers) to introduce a home care work placement to them. Accordingly, the purpose of the Cooperative’s management is not to make a profit, but to create decent jobs for female informal and middle- and older-aged workers who have little-education, low-skills, and are lower-income earners, and improve their quality of life (KWWA 2009: 51). The significant difference between the House Manager’s Cooperative and the private agents is that the Cooperative provides its members with various kinds of education, such as primary education, character-building education and technical education for becoming a skilled home care worker. Through this vocational education, a relationship of trust between the cooperative and its customers (i.e., in this case, the people who need a home care worker) is established, the workers earn the respect of the customers, and that leads the home care workers to improve their social status (KWWA 2009: 53). Moreover, by participating in this cooperative society, the members who had been socially isolated, could form new relationships among the membership and come to have the consciousness that together they belong to the same cooperative society, (KWWA 2009: 53) and that can provide the basis of their “labor society.”

Moreover, in 2009 the Ansan branch of the KWWA established a mutual aid society as a credit cooperative association for poor women who would otherwise have a difficult time obtaining a loan from a bank by themselves. The founding members were women who had worked and been supported at the Yangji self-sufficiency center attached to the Ansan branch of the KWWA for more than five years.4 It was an attempt to develop a kind of social enterprise by the KWWA to provide a social safety net to socially vulnerable, informal women workers, who existed in the blind spot of the social welfare system and were entirely excluded from it. This was unlike a traditional and typical mutual aid society established for the purpose of supplementing the existing social welfare system. For example, welfare recipients and people on the poverty line have to undergo a rigorous investigation concerning their credit standing, and then have to face the difficulty of searching for a guarantor for a loan when they urgently need the money to cover such things as medical fees or house rent even though it might not be a great deal of money (KWWA 2009: 71, 73). And so, the mutual aid society established by the Ansan branch of the KWWA made loans to the poor women who had great difficulty in approaching the banks for loans, by making their deposits and contributions the capital from which they could draw.5 In addition to not only being able to conveniently borrow money, through the activities of self-helps and cooperation with the members, they could also create a fellowship in a kind of community where they recognized each other and shared their lives (KWWA 2009: 74-75). A fellowship like this ties together and creates bonds between informal women workers who are scattered and isolated, and that can be the basis of their “labor society”.

Specifically, it is notable that just after this venture by the KWWA, the Inchon branch of the KWTU also established a mutual aid society in 2010, which tried to involve socially vulnerable, informal women workers, who are difficult to organize into a trade union. It lends money to them at low interest6, and furthermore, through installment savings, manages funds for members for their retirement or old age (Eun 2010: 31; Eun 2012: 166), and this is acknowledged as a social enterprise by a trade union (Eun 2010: 23-24). Additionally, the mutual aid society by the KWTU aims at building a welfare cooperative based on the local community by obtaining the support of the local government and citizens’ organizations, and expanding the sphere of its activity into improving the quality of life of “the socially vulnerable strata,” including female irregular workers and providing them with social welfare (Eun 2010: 23-24).

Thus, the KWTU and the KWWA in cooperation with each other tried to include many of the female irregular workers, into its new activities such as the mutual aid society or the social enterprise; these were women who could never have been organized within the framework of the present trade unions. These specific endeavors of the KWWA and the KWTU are regarded as illustrations of the fact that a mutually complementary relationship between a trade union and a cooperative society or social enterprise is not only significant but offers a new model of trade unionism for organizing informal female irregular workers.

490% of the women who work at the Yangji self-sufficiency center with the goal of being self-sufficient are single mothers (KWWA 2009: 69). 5Although the upper limit for the loan is set at 70% of the payment of installment, even though the amount of payment is small, the members can obtain loans by the mutual aid society when it is urgently necessary. (KWWA 2009: 72). 6The interest rate on loans is 3% (Eun 2010: 31). When we compare it with the prime rate of 7~8% to the best corporations, we can better understand how low it is.