Welfare state modelling has long been an important area of comparative social policy (Esping-Andersen 1990, 1999; Ferrera 1996; Gough and Wood 2004; Bambra 2005

This article contributes to these two responses by implementing two analytical tasks. The first task is to expand the health care decommodification index developed by Bambra (2005

This article starts by examining the arguments by Walker and Wong (2004, 2005) concerning the marginalisation of East Asian countries in the comparative research on welfare. This is followed by a discussion of how the health care decommodification index has been constructed. The third part discusses the contribution the health care decommodification index makes toward an examination of Walker and Wong’s arguments.

Marginalisation of East Asian Countries

In response to the “three worlds of welfare” thesis presented by Esping-Andersen (1990), there are a number of studies on welfare typologies (Bambra 2005

To illustrate their argument, Walker and Wong (1996, 2004) discuss the welfare arrangements in Hong Kong and China as key examples. The Hong Kong government has long played an important role in the provision of housing, education, and health care (Wong, Chau, and Wong 2002; Walker and Wong 2004). Because of its colonial background, the way in which the Hong Kong government provides education and health care is indebted to the ideas from the UK (Ramesh and Holliday 2001; Holliday and Wilding 2003). The government in mainland China has been keen to re-cast welfare responsibility from total reliance on the state to the incorporation of individual responsibility by social insurance and forced savings (Walker and Wong 2004). In re-establishing the social insurance programmes, the Beijing government has borrowed ideas from the World Bank. Since Hong Kong and mainland China have actively provided social welfare, it is not reasonable to exclude them from mainstream comparative studies on welfare.

Walker and Wong’s view on the marginalisation of East Asian countries in comparative studies on welfare has been discussed in both the East and the West (Kennett 2001, 2004; Walker and Wong 2005; Hill 2006; Chau and Yu 2009, 2011). Their arguments are supported by a number of studies. These include those focusing on identifying similarities in welfare arrangements between East Asian countries and Western countries, and thus drawing attention to the potential contributions of East Asia in comparative studies on welfare to the search for the fourth world of welfare capitalism.

Studies indicate that some welfare policies, such as minimum wage and welfare-to-work measures for single parents, are found both in the UK and Hong Kong (LegCo 2005, 2007, 2008). It is not unusual that East Asian countries borrow experiences of providing social welfare from some of the 18 OECD members studied by Esping-Andersen (1990) such as Germany and the UK (Ramesh and Holliday 2001; Chau and Yu 2005; Walker and Wong 2005). Investigators (Jones Finer 1998; Yu 2008) also point out that some policies adopted by Western governments are indebted to ideas from the East. For example, Jones Finer (1998) argues that Blair’s thinking manifest in the New Labour policy agenda in the UK was inspired by his understanding of East Asian productivism. In view of the similarities in the ways in which some of the 18 OECD members studied by Esping-Andersen (1990) and East Asian countries organise social welfare, some analysts such as Yu (2008), Karim, Eikemo, and Bambra (2010), and Witvliet et al. (2011) point out that East Asian welfare regimes receive less attention than they deserve from comparative studies on welfare, and hence, they suggest that East Asian countries should be included.

Since Esping-Andersen (1990) put forward the “three worlds of welfare capitalism” thesis, there has been a rising interest in identifying the fourth world of welfare capitalism (Gough 2004; Bambra 2005

Some studies provide support for the existence of these two conditions (Jones 1993; Wilding 2000; Gough 2004). In response to the question of whether East Asian countries might fit into Esping-Andersen’s typology, Jones’ argument is that they do not fit (Jones 1993). Some analysts observe that East Asian countries share a common cultural heritage in Confucianism (Rozman 1991; Rieger and Leibfried 2003). Wilding (2000) identifies six common features of East Asian welfare: Low public spending on welfare, the facilitatory regular role of the state in the form of a productivist social policy focused on economic growth, general dislike of the term “welfare state,” strong residualist aspects, limited commitment to social citizenship, and the central role of family. Gough (2004) argues that a number of countries in East Asia such as Malaysia, South Korea, Thailand, and Indonesia can be termed as productivist welfare regimes because they meet the following four criteria: subordination of social policy to economic policy goals, social policy concentrated on social investment, the focus of the state on the regulatory role rather than the role of provider, and social policy mainly as an instrument for giving legitimacy to the regime.

However, some investigators (Kwon 1998; Kennett 2001) stress that the favourable conditions for the existence of a distinctive East Asian welfare model do not exist. Kwon (1998) argues that, although the East Asian experience is distinctive and different from the Euro-American model’s current social policy discourse, evidence suggests that the welfare arrangements in the countries are diverse and the similarities are insufficient to support an all-encompassing East Asian welfare model. In comparing the differences and similarities between the welfare systems in East Asia, analysts observe that there are two subgroups–Hong Kong and Singapore versus Taiwan and South Korea (Ramesh 2004). Ku and Jones Finer (2007, p. 124) point out that the diversified findings of East Asian welfare studies may simply be the result of the nature of actual conditions in East Asia: “encompassing radical differences in the levels of economic development, political democratization, social and demographic change, and stages of transition from varied legacies of colonialism and communism.”

As will be shown later, this article intends to show important similarities between the East Asian countries and the non-Asian OECD countries and to contribute to the debate on whether East Asian countries form the fourth world of welfare capitalism by developing the health care decommodification index covering the 18 OECD countries studied by Esping-Andersen (1990) and five additional East Asian countries. Before going into the details of these issues, the next section focuses on methods for developing the health care decommodification index.

1A number of welfare regime studies do not include East Asian countries (except Japan). Examples of such studies include projects by Bambra (2004, 2007), Castles and Mitchell (1993), Esping-Andersen (1990; 1999), Korpi (2000), Korpi and Palem (1998), and Pitruzzello (1999). 2Western countries refer to Western European countries and those coming from the Anglo-Saxon world. Most of the 18 OECD countries studied by Esping-Andersen (1990) belong to this group. 3In their article published in 2004, Walker and Wong argue that “…the exclusion of East Asian welfare systems from the mainstream comparative welfare state literature, including what is widely regarded as the core text on the subject (Esping-Andersen, 1990), artificially limits the scope of comparative social policy” (Walker and Wong 2004, p. 117). This argument reflects Walker and Wong’s belief that the scope of comparative social policy can be extended if more East Asian countries are included into such comparative studies on welfare as was done by Esping-Andersen (1990).

Health Care Decommodification Index

In presenting the thesis on the “three worlds of welfare capitalism,” Esping-Andersen (1990) has classified the 18 OECD countries into three types: liberal (Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, the UK, and the USA), conservative (Australia, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, and Switzerland), and social democratic (Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden). This classification is based on the principle of labour market decommodification. The strength of Esping-Andersen’s work is that it makes comparative policy analysts more aware of the importance of studying not only the aggregate welfare state expenditure but also the impact of social welfare on commodity relations. Unsurprisingly, since the publication of Esping-Andersen’s study on the “three worlds of welfare capitalism,”comparative studies have paid more and more attention to the outcomes of welfare provision. However, Esping-Andersen’s work is not without limitations. For example, analysts (Bambra 2005

Bambra (2005

In developing the health care decommodification index, the current article has borrowed the definition of health care decommodification provided by Bambra and her method for assessing this concept. However, the study on health care decommodification conducted in this article differs from Bambra’s in two important aspects. This article examines 23 countries rather than 18 countries. Moreover, it has used more recent data. In building the health care decommodification index, Bambra (2005

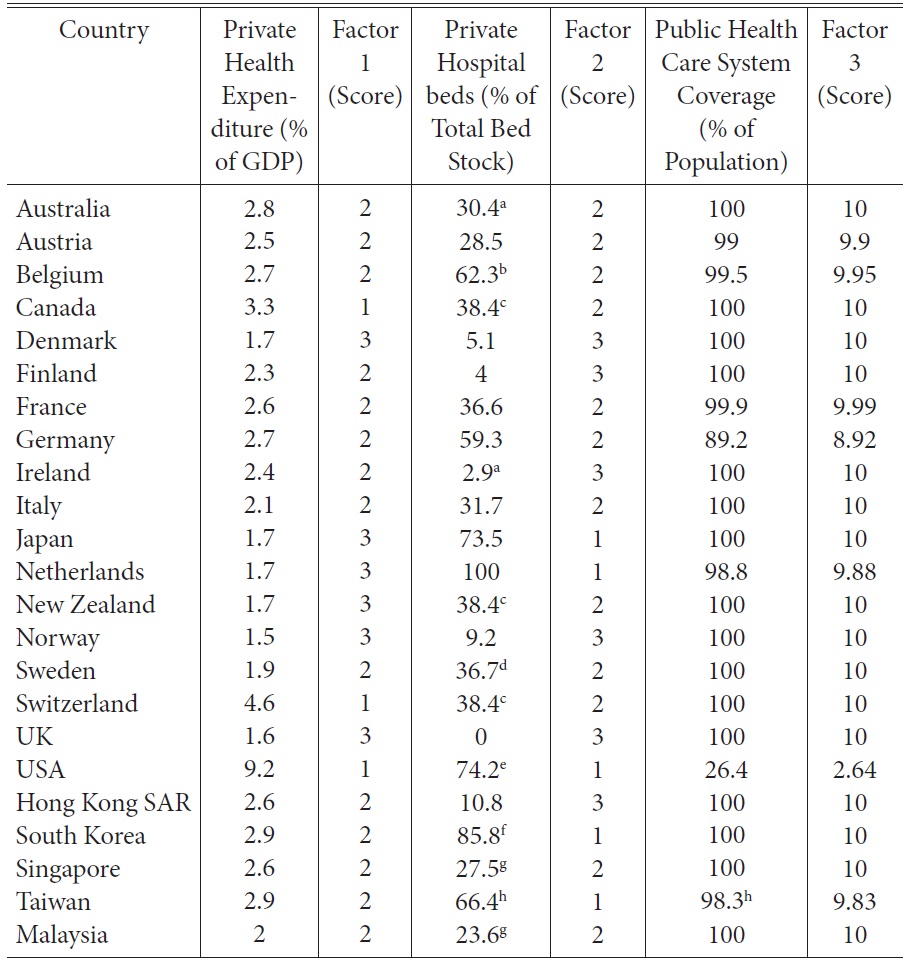

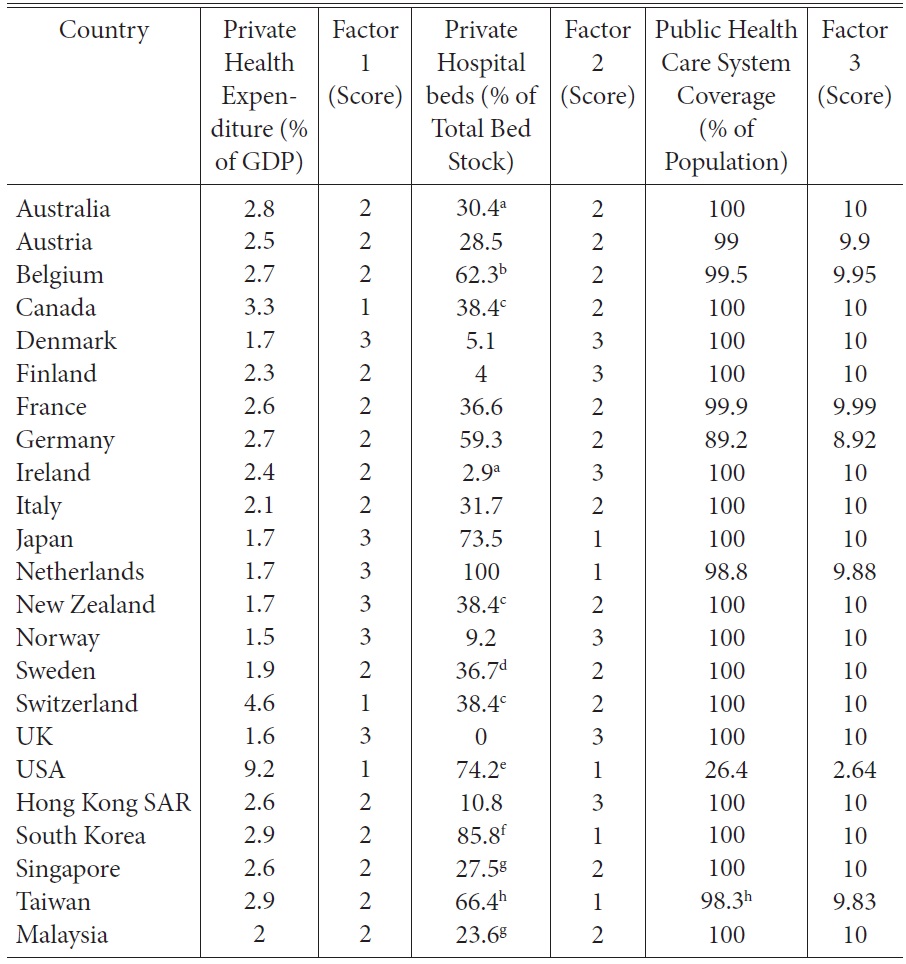

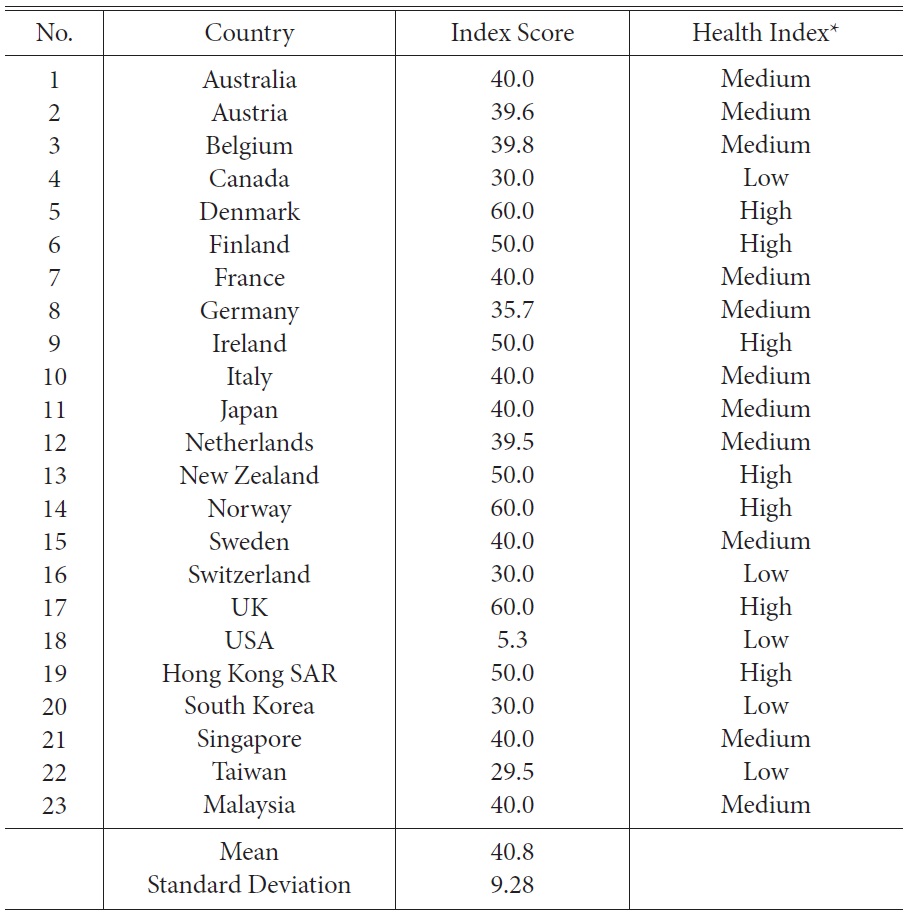

[Table 1] Health Index Data (2009)

Health Index Data (2009)

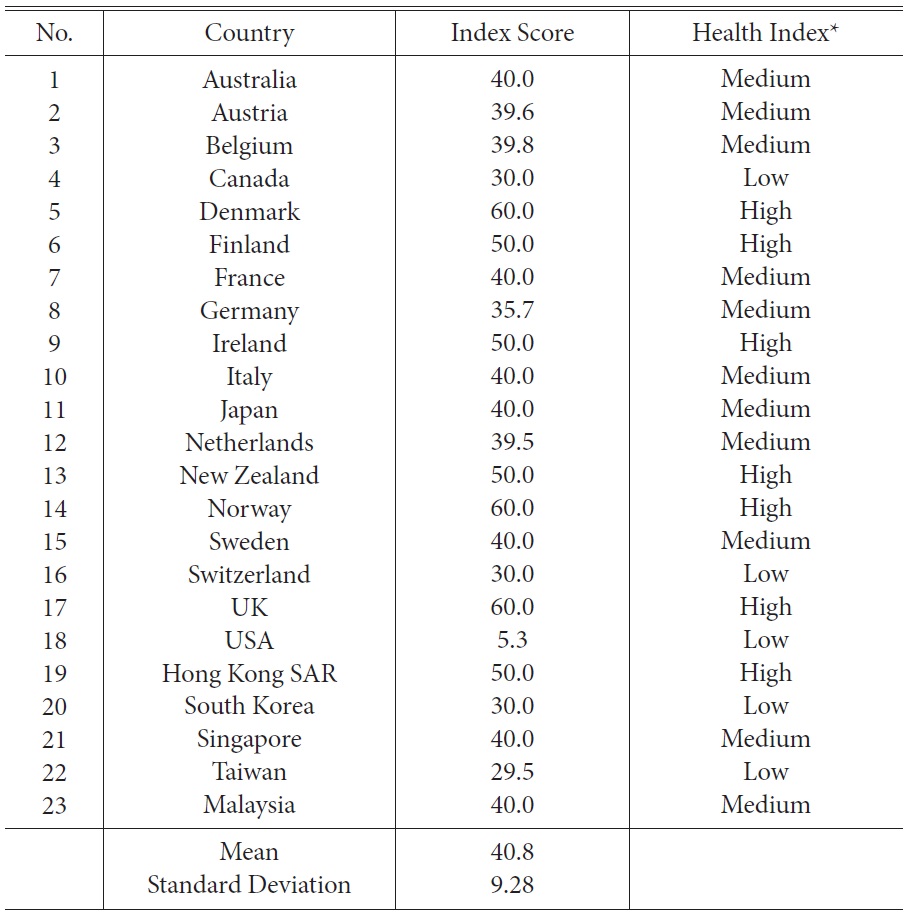

[Table 2] Health Care Decommodification Index

Health Care Decommodification Index

Table 1 outlines the unstandardised data for each of the health care decommodification measures and shows the spread of country scores for each of the three measures.

Table 2 indicates the health care decommodification index based on Esping-Andersen’s classification method. This index shows a wide range of health care decommodification scores, from 5.3 for the USA to the highest score awarded to the UK (60), Denmark (60), and Norway (60). The majority of the countries fall into the group with medium level of health care decommodification. They include two East Asian countries (Singapore and Malaysia) and nine OECD members (Australia, Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Sweden, and the Netherlands) studied by Esping-Andersen (1990). The UK, Denmark, Norway, New Zealand, Ireland, Finland (OECD countries), and Hong Kong (an East Asian country) belong to the highest health care decommodification group.

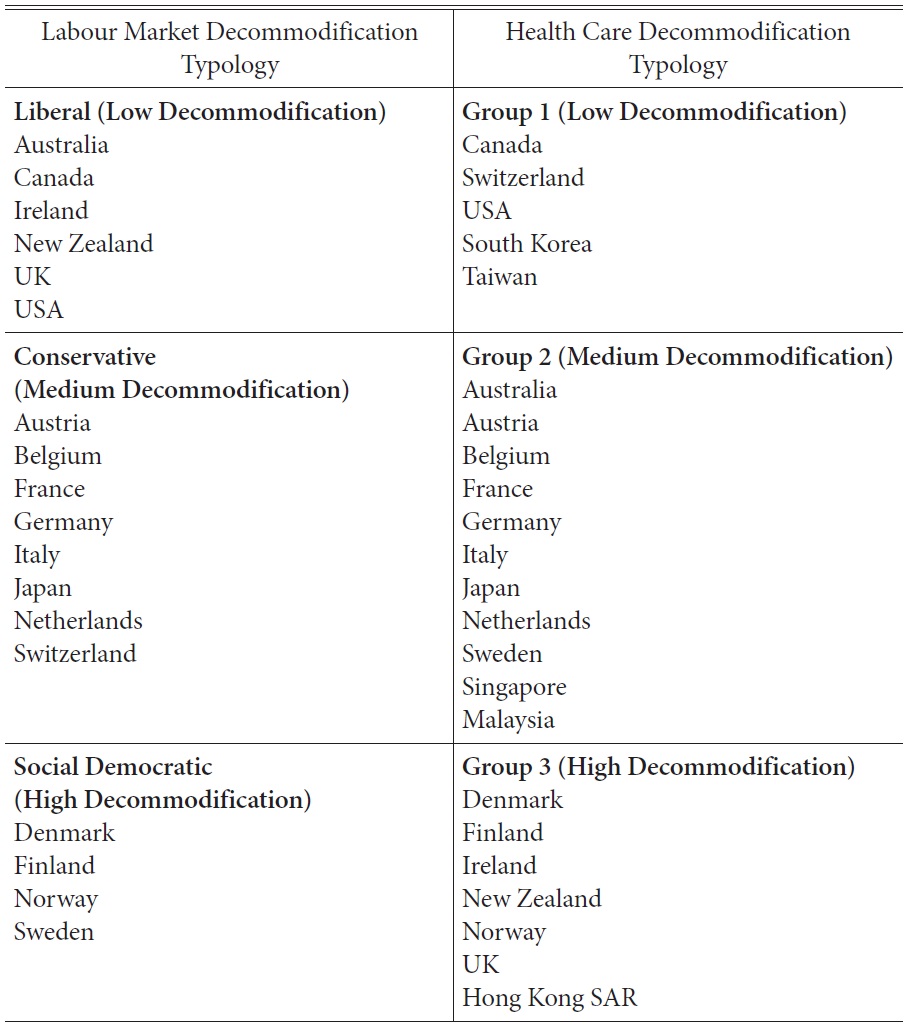

The health care decommodification index lends support to Walker and Wong’s views on marginalisation of East Asian countries in comparative welfare studies. Firstly, the empirical evidence provided by this index shows important similarities in the welfare systems of the 18 OECD members studied by Esping-Andersen (1990) and five additional East Asian countries (Hong Kong, South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, and Malaysia). Hong Kong, South Korea, Singapore, and Malaysia are among the 16 countries having 100 percent public health care system coverage. Singapore and Malaysia have the same index score (40) as nine of the OECD countries (Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Japan, Italy, Australia, Sweden, and the Netherlands), while Hong Kong (50) and six of the OECD countries (namely, Finland, Ireland, New Zealand, Denmark, Norway, and the UK) share the same index score. South Korea (30) and Taiwan (29.5) are in the same category (the low health care decommodification group) with three of the OECD members (the USA, Canada, and Switzerland).

Secondly, the health care decommodification index shows that the scope of the social policy studies could be expanded by conducting comparative projects covering the 18 OECD members studied by Esping-Andersen (1990)and five additional East Asian countries. This point is backed up by the fact that the findings generated by the health care decommodification index provide insights into two issues of interest to analysts of welfare regimes concerned with whether East Asian countries form the fourth world of welfare capitalism and whether welfare regimes have internal policy homogeneity.

As shown above, there is a debate on whether the two preconditions– internal homogeneity and external heterogeneity–for the existence of the fourth world of welfare capitalism constituted by East Asian countries exist or not. The empirical evidence provided by the health care decommodification index does not support the existence of these two conditions. As shown in the previous paragraphs, there are important similarities between East Asian countries and the OECD countries in discussion. Moreover, table 2 provides evidence of important differences between East Asian countries–Taiwan and South Korea belong to the low health care decommodification group; Japan, Singapore, and Malays i a belong to the medium healt h care decommodification group; and Hong Kong is located in the high health care decommodification group. The difference between the index score of Hong Kong (Hong Kong has the highest score among the six East Asian countries) and that of Taiwan (Taiwan has the lowest score among the six East Asian countries) is 20.5, and there are four countries with scores higher than Taiwan but lower than Hong Kong.

[Table 3] Labour Market Decommodification Typology and Health Care Decommodification Typology

Labour Market Decommodification Typology and Health Care Decommodification Typology

Health care clearly cannot represent all elements of social welfare, but the fact that health care is one of the largest areas of welfare regime must not be overlooked (Bambra 2005

Moreover, while both Hong Kong and the USA are often seen as examples of the “liberal welfare regime” (Wong, Wan, and Law 2009; Karim et al. 2010), they belong to different groups in the health care typology. As shown in table 1, USA has much higher private expenditure as a percentage of GDP, higher number of private hospital beds as a percentage of total bed stock, but lower coverage of public health care system than those of Hong Kong. These findings are also backed by other commonly used health indicators such as the life expectancy and infant mortality rates. According to the Central Intelligence Agency (2012), Hong Kong is among the top countries in achieving these impressive records; it ranks fourth and third for the life expectancy of males (79.4) and females (85.1), respectively, and ranks fourth lowest in infant mortality rate (2.9). The performance of the USA is much less impressive; in life expectancy, it ranks fourth from the last and second from the last for males (76.1) and females (81.1), respectively. Moreover, its infant mortality rate is the second highest among the 23 countries.

The empirical evidence provided by health care decommodification index makes us aware of the possible problem of using a proxy measure of the overall welfare state provision. To avoid this possible problem, it is worth considering developing different welfare typologies based on different types of welfare, and then comparing the empirical evidence provided by these typologies.

As the last part of this section, it is necessary to highlight the limitations of the health care decommodification index developed in this article. Firstly, this new index only covers six East Asian countries rather than all countries in East Asia. Secondly, it only focuses on health care rather than all essential elements of social welfare. Despite these two limitations, the health care decommodification index provides support for Walker and Wong’s arguments concerning the marginalisation of East Asian countries in comparative studies on welfare. Firstly, it shows important similarities in the welfare arrangements between the 18 OECD members studied by Esping-Andersen (1990) and the five additional East Asian countries (Hong Kong, South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, and Malaysia). In view of this evidence, we should avoid both under-emphasizing the similarities between some of the 18 OECD countries and East Asian countries, and excluding East Asian countries from comparative studies on welfare. Secondly, the health care decommodification index shows that important issues concerning welfare typologies can be studied through comparative projects that cover the 18 OECD members studied by Esping-Andersen (1990) and the five additional East Asian countries.

Two analytical tasks have been carried out in this article. The first is to expand the health care decommodification index developed by Bambra (2005

So far, this article has focused only on health care. The technical and the philosophical approaches should be further applied to the study of other welfare areas such as education decommodification and housing decommodification. This can be done by collecting comparative data on housing and education in East Asian countries and most of the OECD countries studied by Esping-Andersen (1990), followed by making use of the data to inform the debate on the fourth world of welfare capitalism and the policy coherence of welfare regimes.