본 연구는 아동시설에 거주하고 있는 청소년 대상으로 설문조사를 통해 이들이 지각하고 있는 사회적 지지가 우울증, 자아 존중 감에 영향을 어떻게 미치는지를 탐색해보았다. 특히 자아존중감이 사회적 지지와 우울과의 관계에서 매개효과를 나타내는지를 검증하였다. 사회적 지지가 독립변수로, 청소년의 우울증을 종속변수로, 자아 존중 감을 매개변수로 설정하였다. 본 연구의 조사대상자는 편의 표본 추출 방법으로 경기도 아동보육시설에 거주하는 240명을 대상으로 설문조사를 실시하였다. 본 연구결과를 살펴보면, 사회적 지지는 청소년의 심리, 정서적 안정에 긍정적인 역할을 하는 것으로 나타났는데, 사회적 지지가 높을수록 시설아동의 우울증이 낮게 나타났고 자아존중감은 높게 나타났다. 또한 사회적 지지가 높을수록 자아존중 감이 높게 나타났다. 자아존중 감의 매개변수를 검증한 결과 사회적 지지는 자아존중 감을 매개하여 우울증에 영향을 주는 것으로 나타났다. 본 연구 결과를 토대로 보육시설에 거주한 청소년의 우울증을 경감하기위한 실천적 함의를 제시하였다.

Historically, an orphanage was an institution dedicated to the care and up bringing of children who have lost their parents, and an upsurge in such institutions was observed immediately post Korean War.However, at the end of 1997, Korean economy entered a crisis. The number of orphaned adolescents has increased compared to 40 years ago. The economic orphans are the most dramatic manifestation of how Korean economic crisis is shattering the family unit. Orphanages across nation are reporting similar increases in so call “ IMF orphans” named for the International Monetary Fund which delivered a record bail out South Korea. Adolescents in orphanages are often abandoned by their families as infants or even school age.

Adolescents living in institutions are reported to display a variety of behavior problems, including aggressive and anti-social behaviors, inattention, hyperactivity, depression, worry, fear, indiscriminate friendliness, poor quality peer relationships, loneliness anxiety, oppositional behavior, and emotional regulation difficulties(Frank et al, 1996; Hobbs, et al., 1999; Kim & Kim, 2003; Myers & Jones, 2003). Furthermore, prior to abandonment, adolescents may sustain neglect, physical, emotional, and sexual abuse when they are living with their parents. This traumatizes children psychologically, placing them in need of immediate and continuous specialized help. Physical and developmental growth can be similarly affected as a result of this traumatic past. Frank et al., (1996) has demonstrated that young children in institutional care are extremely vulnerable to psychological problems. In short term, orphanages put young children at increased risk of delayed language development, other developmental problems, and infectious illnesses. In the long term, institutionalization in early childhood increases the likelihood that adolescents will grow into psychologically impaired and economically unproductive adults.

Major issues that adolescents in institutions often confront are depression, loneliness, low self-esteem, and a need for social support(Kim & Kim, 2003; Myers & Jones, 2003; Yoo, Han, & Choi, 2001). Adolescents in institutions are at greater risk for depressive symptoms than are their peers who live their own family(Choi, Yoo, & Han, 2002; Frank et al., 1996). Particularly adolescentsreared in institutions have been found to have a higher level of depression than adolescents raised by families.

Self-esteem is very influential factors in the lives of adolescents.Self-esteem is described as a pattern of beliefs that individuals possess regarding their self-worth and is based on perceptions of personal experiences and feedback from significant others(Rosenberg, 1965). Also, self-esteem is a primary internal resource that may serve to enhance resilience in the face of stress. Specific evidence of a link between self-esteem and depression has been provided by a number of recent research studies that report associations between self-esteem and a range of measures of depression(Orth et al., 2008). Empirical research has also found that low self-esteem is strongly related to feelings of depression, hopelessness, and substance use for adolescents(Kernis, et al.,1991; Lewinsohn, et al., 1988). Self-esteem significantly reduces psychological symptoms, especially depression and buffers the emotional consequences of stress as well (Mcwhirter, et al, 2002). Correlations of global self-esteem with depression typically vary between -.27 and -.56, depending on measures and samples(Kernis, et al.,1991; Lewinsohn, et al., 1988). Individuals with unstable high self-esteem were more likely to experience anger and depression than individuals with stable high self-esteem, and individuals with low self-esteem. Therefore, enhancing adolescent self-esteem would help to reduce the risks of maladjustment for adolescents.

Cohen & Syme(1985) defined social support as “resources provided by other people”, referring to a wide variety of social networks and relationships. Social support is considered an important resource for reducing people’ depression and producing a positive impact on psychological well-being (Baron & Kenny, 1996; Cohen & Wills, 1985; Curona & Ruseel, 1990; Delgard & Tambs, 1995; Hobfoll & London, 1986; Moon & Lim, 2009;Olstad et al., 2000). People with high levels of social participation have reported having a great degree of life satisfaction(Frank et al.,2004; Wilson et al., 1990). The absence of social ties might causing chronic depression. Adolescents in institutions who have poorer social networks or who fail to utilize their social networks experience greater depression. children who possessed higher density network tend to report less depression than those with less dense network. Feeling of loneliness, low levels of self-esteem and low levels of social support are highly correlated with depression in both male and emale.(Frank et al.,2004; Wilson et al., 1990).

Empirical research has found that social support from other people can play an influential role in self-esteem. Having positive relationships with significant others is beneficial to enhancement of self-esteem(King et at., 2009; Wilson et al., 1990). Adolescents who have positive relationships with their significant others are more likely to experience warmth and acceptance, and support from positive interactions in these relationships, so they are more likely to develope feelings of self-worth, adequacy, and self-confidence which are essential elements of higher self-esteem (King et at.,2009; Wilson et al., 1990).

Research study has done to teat the relationship among social support, self-esteem and depressive symptoms. Social support may strengthen a person’s self-esteem and may be particularly important in reducing depressive symptoms when dealing with a stressful situation(Petra & Ronald, 2003; Simoni, et al., 2005).

Research has suggested that psychological resourcefulness, such as mastery or self-esteem, may mediate the relationship between social support and psychological well-being.(Petra & Ronald, 2003; Simoni, et al., 2005). Evidence has shown that self-esteem not only directly reduces psychological distress, but also buffers the negative effects of stressors. Mediating effects of self-esteem are found especially in the studies of populations that experience intense and chronic stress, such as disaster. Research studies have indicated a strong and consistent association between various measures of social support and superior self-concept, with some support for self-esteem mediating the relationship between social support and depression(Petra & Ronald, 2003; Simoni, et al., 2005). For example, Petra and Ronald(2003) found that self-esteem mediated the relations between social support and adjustment. Social support was associated with high self-esteem, which in turn increased optimism and was related to decreased depression. Results from a study of 738 postpartum women indicated that self-esteem mediated the effect of the quality of the primary intimate relationship on depressive symptoms(Hall Kotach Browne & Raven, 1996). Similarly, Pearlin et al., (1983) hypothesized that self-esteem and mastery, or personal control, mediates the effects of social support in individuals experiencing stress, or in populations with uniformly high levels of stress. Fukukwawa et al., (2000) also examined the relationship between social support, self-esteem, and depression. Structural equation modelling was used in which depressed affect was predicted directly from social support and indirectly mediated through self-esteem. Result showed that social support reduced depressed effect through an increase in self confidence and a decrease in self-depression. Social support appeared to influence depressed affect only when mediated by self-esteem.

On the basis of the literature review, the research study developed the following hypotheses; Adolescents’perceived social support are hypothesized to directly reduce the depression. As the perception about social support by adolescents increases, their level of depression tends to decrease. Adolescents’ perceived social support are hypothesized to contribute to adolescent’s depression at indirectly through high self- esteem. Adolescents who have high perceived social support enhance self-esteem, which, in turn, reduce the probability that adolescents experience depression. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to examine the relationships among perceived social support, self-esteem, and depression, and the most important significant aspect of this research study is testing mediating effect of self-esteem. This will enable helping professionals to better understand psychological characteristics of children in institution.

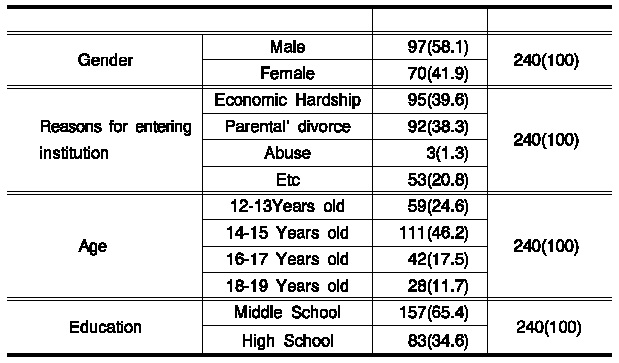

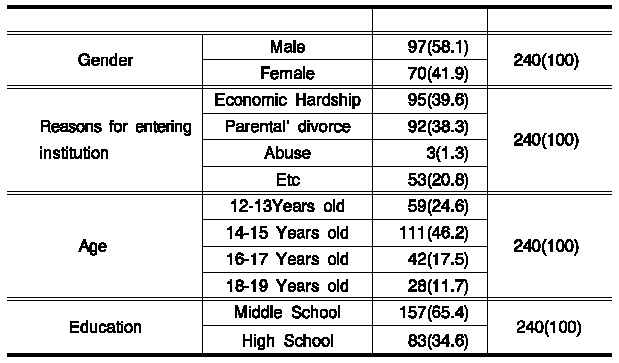

This research study used a convenience sampling method, and the sample of this study was drawn from 8 child welfare facilities in Gyeonggi-Do. A total of 310 questionnaires were sent to institutionalized adolescents. The adolescents were given a copy of the informed consent form. A total 255 surveys were completed, and15 surveys were eliminated from the analysis since a preponderance of the participants’ s data was missing. Of 240 institutionalized adolescents, 58.1 % of research participants were female and 41.9% were male. The respondents had a mean age of 14.8 years (SD = 4.3: range = 12- 18). <Table 1> shows the reasons for admission into care. Approximately 77% indicated family economic hardship and parental divorce as reasons for entering the child welfare facilities.

[Table 1] Demographic Characteristics of the Sample(n=240)

Demographic Characteristics of the Sample(n=240)

2.2.1 The center for EpIdemIologIcal Studles Depression Scale

Depression was assessed by the Center for Epidemiological Depression Scales (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). The CES-D is a 20-item scale that requires respondents to determine whether they have experienced symptoms usually associated with depression, with emphasis on the effective component and depression mood (e.g., depressed mood, feelings of worthlessness, feeling of hopelessness, loss of appetite, poor concentration, sleep disturbance). Responses were coded on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from zero (rarely or none of the time) to three (most or all of the time). Sixteen items assess cognitive, affective, behavioral, and somatic symptomatology associated with depression, and 4 items assess positive affect. The CES-D has very good internal consistency with alpha of .85 for general population and .90 for psychiatric population(Fischer & Corcoran, 1994). The CES-D has been reported to possess excellent concurrent validity, good known-group validity and good discriminant validity (Fischer & Corcoran, 1994). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the CES-D was .82.

2.2.2 Multi-dimeneional Scale for Perceived SocIal Support

Perceived social support was measured by the Multi-dimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support(MSPSS; Zimet et al., 1988). The MSPSS is a 12 item measure that comprises three facets: support from family, support from friends, and support from significant others. Participants are asked to rate their degree of agreement on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from one (strongly disagree) to five(strongly agree).Greater scores indicated higher levels of perceived social support. In prior studies, the Cronbach’s alphas for the MSPSS scoresranged from .88 to .93 (Canty-Mitchell & Zimet, 2000; Zimet et al., 1988), and the Cronbach’s alphas for th e Family, Friends, and Significant Other subscales were .91, .89, and .91, respectively (Canty-Mitchell & Zimet, 2000).The MSPSS has excellent internal consistency, good test-retest reliability and adequate validity (Zimet et al., 1988). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the MSPSS was .90.

2.2.3 Coopersmith Self-Esteem Inventory (CSEI)

Self-esteem was measured by the Coopersmith Self-Esteem Inventory. The CSEI is a 50 item scale designed to measure self-esteem. The Self-Esteem Inventory (Coopersmith, 1967) was used as the measure the respondent’s attitudes toward self in personal, social, family, and academic areas of experience.Participants respond to a 5-point Likert scale(1= strongly disagree, 5= strongly agree). Responses to all the 50 items have to be summed up to yield the final composite score with a range for 50 to 250. In a study by Chang(2003), internal consistency reliability coefficients of CSEI was. 88 as measured by Cronbach’s. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the CSEI was .85.

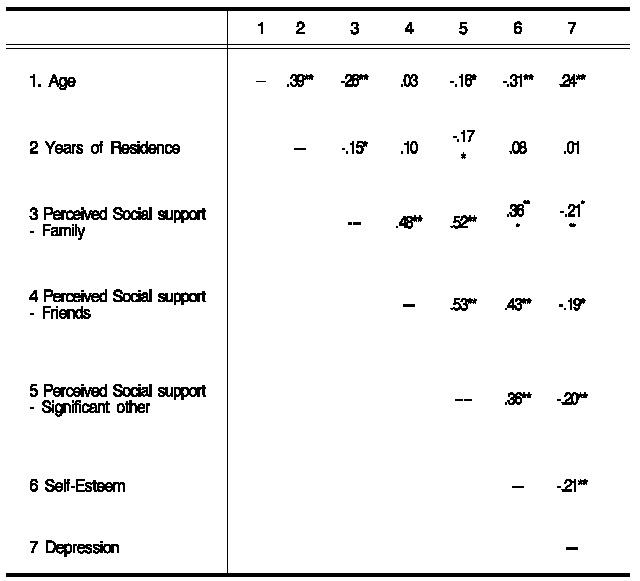

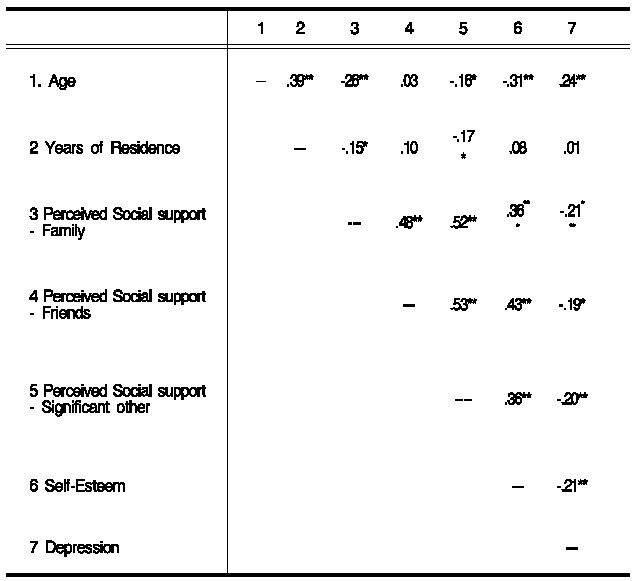

Correlation coefficients among the demographic variables, self-esteem, depression, and social support, were examined. Pearson production-moment correlation coefficients are reported in Table 2. The most consistent significant relationship among the variables involved self-esteem. The MSPSS was used to measure children' perceived social support from each subscale: family, friends, and significant others. Self-esteem was significantly and positively correlated with all three sub-scales of MSPSS.

This indicated that as social support increases, self-esteem increases. Bivariate correlation between dependent variable and demographic variables show the age (r=24, p<.01), self-esteem (r=-.21, p<.01), social support from significant other (r=-.20, p<.01), social support from family (r=-.21, p<.01), social support from friends(r=-.19, p<.05) were significantly related to participants’depression. However, there was no relationship between depression and years of residence.

Correlation Matrix

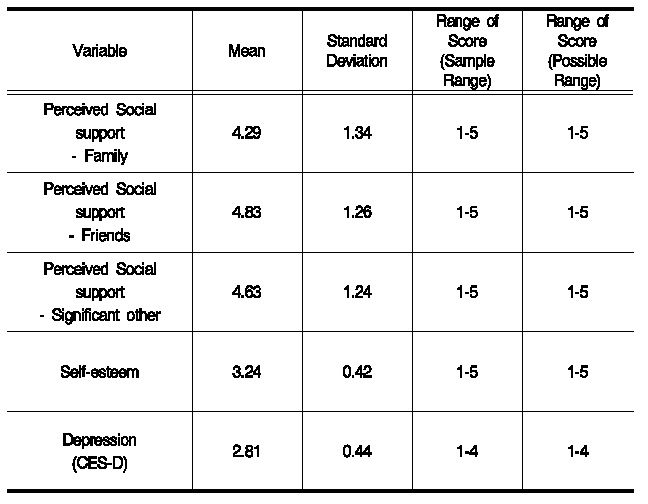

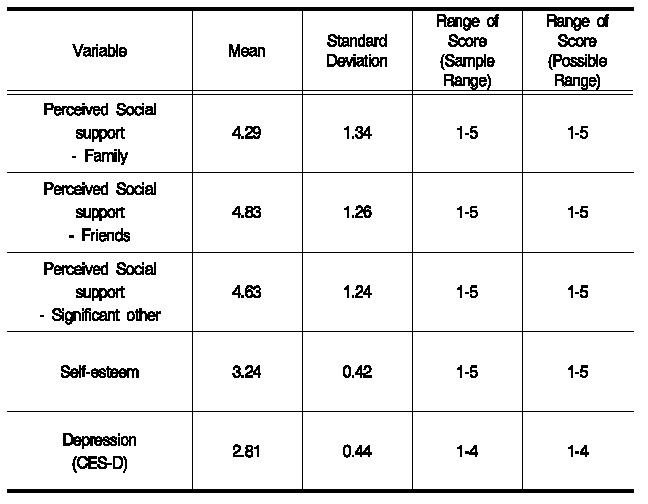

The means, standard deviations, and range of the study’s variables are presented in the <Table 2>. The CES-D scores ranged from 1 to 4, with a mean of 2.81(SD=0.44). Compared to other studies, research participants reported higher mean scores on the CES-D. For example, the study conducted by Radloff(1977) indicated that mean for the general population of respondent ranged from 7.94 to 9.27. The self-esteem scores ranged from 1 to 5, with a mean of 3.24(SD=0.42). Perceived social support from family scores ranged from 1 to 5, with a mean of 4.29(SD=1.34), social support from friends scores ranged from 1 to 5, with a mean of 4.83(SD=1.26), and social support from significant others scores ranged from 1 to 5, with a mean of 4.63(SD= 1.24).

[Table 3] The Means, Standard deviations, and Range of the study

The Means, Standard deviations, and Range of the study

3.2 TestIng mediation effect of self-esteem

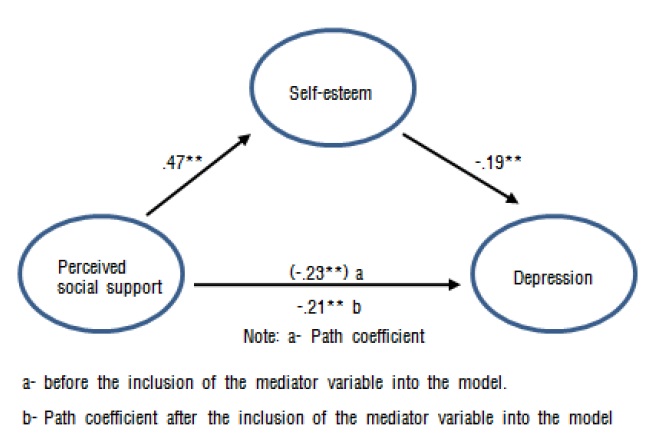

To test the mediating model, a series of regression analyses were conducted and the strengths of the path were estimated. One of the most widely used methods to test mediation is the Baron and Kenny criteria(1986). Consistent with Baron and Kenny (1986), for self-esteem to function as a mediating variable between perceived social support and depression, the following conditions must be met; a) a significant relation between the predictor variable (perceived social support) and dependent variable (depression), b) significant relations between the mediator(self-esteem) and both the predictor and dependent variables, and c) a reduction of the relationship between the predictor and dependent variable to non-significance when the mediator is included. In the conceptual model, adolescents’perceived social support are hypothesized to directly reduce the depression. As the perception about social support by adolescents increases, their level of depression tends to decrease. Adolescents’perceived social support are hypothesized to contribute to adolescent’s depression at indirectly through high self- esteem. Adolescents who have high perceived social support enhance self-esteem, which, in turn, reduce the probability that adolescents experience depression.

A bivariate analysis provided evidence that significant relationships existed between predictor variable(perceived social support), mediating variable(self-esteem), and dependent variable(depression).

A series of regression analyses were used to test mediating model. in the first step, depression was regressed onto perceived social support and a significant relationship was determined (B= -21, p<.05). In the second step, self-esteem was regressed on perceived social support, which demonstrated a significant relationship (B=.47, p<.01). In the third step, depression was regressed onto self-esteem. A significant relationship was determined between self-esteem and depression(B=-21, p<.01). In the final step, depression was regressed onto perceived social support in the first step, and then onto self-esteem in the second step of a two-step regression. The effect of perceived social support on depression was less in the final step (B=.-21,p<.01) compared with the first step (B=.-23, p<.01), supporting self-esteem as a mediator of the relation between social support and depression. <Figure 1> presents these relationships.

Ⅳ. ImpIIcatIons and LImItatIons of This Research Study

This research study highlights the importance of social support and self-esteem and examines the relationship between among perceived social support, self-esteem, and depression. This research has demonstrated that adolescents in institutions are extremely vulnerable to psychological problems. Adolescents who have poorer social networks or who fail to utilize their social networks experience greater depression. Adolescents’scores on the depression scale in this research study are greater than average score of other adolescents. This result could be explained by the fact that most of the orphanage adolescentshave experienced many traumatic incidents.

This study also shows the importance of social support and self-esteem to positive psychological outcomes. For adolescents in institutions, the effect of low self-esteem on depression has also been found in sample of this research study. Self-esteem was significantly and negatively correlated with depression. The significant inverse relationship between self-esteem and depression found here is consistent with previous research studies(Brage et al., 1993; Kernis, et al.,1991; Lewinsohn, et al., 1988). Such knowledge from this research study results might serve as the basis for designing effective interventions aimed at preventing or reducing depression.

This research study sought to examine the roles of self-esteem on the relationships between perceived social support and depression among institutionalized adolescents. The results from this research study shows that self-esteem mediated the relationships between perceived social support and depression. Findings suggest that increased levels of social support were associated with increased of social support which in turn decreased depression. This research study indicates that self-esteem is the prominent protective resource that adolescents can use against daily negative events Therefore, service provides working with adolescents in residential institutions need toprovide various services that target to increase self-esteem among youth. The findings suggest that interventions targeting depression should include a component of enhancing self-esteem, and that interventions designed for self-esteem should include interventions for depression.

For practitioners, challenging task is to develop a health sense of self for clients, because adolescents reared institution have a poor self-esteem(Kim & Kim, 2003). Negative thoughts about social relations are thought to overlap with stimulate negative thought about the self, which in turn, overlap with the stimulate emotional distress (aldwin & Holmes, 1987). Social relationships are considered to enhance the feelings of self-worth, self-esteem, and the sense of well-being that comes feeling valued by meaningful others.Institutionalized adolescents who reported lower levels of social support were more withdrawn, hopeless about their future, inattentive, and harmful to others than were youth who reported higher levels of social support. Mentoring may provide some of this social support and, hence, improve youth functioning.The relationship generally involves spending quality time together and providing support and guidance, with the aim of helping the young person better negotiate life’s difficulties. In the study of King et at(2009), mentored children were be significantly less likely to be depressed or involved in bullying and fighting at posttest than at pretest. Therefore, mentoring program will be good intervention to increase children’s selfesteem.

The findings from this investigation need to be viewed in light of several limitations. First, the research study was limited by a relatively small sample size. Second, the sampling was another limitation of this research study. Because this research study used a convenience sampling method and did not use randomly or stratified sampling methods, it is failed to ensure inclusion of adolescents in institutions representing all geographical areas. The homogeneity of the sample in this research study may also decrease the probability of being able to generalize the results to institutionalized adolescents with different demographic characteristics. In addition, the high CES-D scores might indicate selection bias. Since the investigators relied on self-report measures, diagnoses of depression could not be confirmed. Therefore, future research study should be conducted with a large, random sample of adolescents from a variety of geographic locations and from different socioeconomic and religious backgrounds.