North Korea’s human rights violations against its own population, for which the authorities should be held responsible, are both egregious and endemic.1) With human rights abuses becoming a matter of daily routine, the rights of North Korean citizens have fallen into a deplorable state with little hope for improvement.2) In particular, reports of extrajudicial killings, disappearances, arbitrary detention, arrests of political prisoners, harsh prison conditions, and torture continue to emerge. Moreover, the state’s judicial system lacks autonomy and routinely fails to provide due process.3) The abuses against North Korean citizens are numerous and diverse.4) Of the seven categories of threats indentified in the 1994 UNDP Human Development Report (HDR), this article focuses on personal security and political security ─the former includes threats from the state through physical torture; the latter includes civil and human rights violence, arbitrary behavior, and a poorly functioning judiciary.

The application of ‘Responsibility to Protect’ to the North Korean case is not new. The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea (HRNK) stated in its report on October 30, 2006, that North Korea’s government had failed in its responsibility to protect its own citizens from the most severe violations of international law, and concluded by urging a robust international response to North Korea’s human rights violations through the UN Security Council.5) Active North Korean Human rights NGOs6) recommended the establishment of a ‘UN Commission of Inquiry’ to assess past and present human rights violations in North Korea. They further requested that a ‘Commission of Inquiry’ determine whether such violations may constitute ‘crimes against humanity,’ and whether specific individuals bear responsibility, making them subject to investigation and possible prosecution.7)

Furthermore, there is continuous discussion within the UN human rights regime on the dire problem of North Korea’s political detention camps. Special Rapporteurs on ‘torture and other cruel, inhumane, or degrading treatment and punishment,’ as well as ‘the right of everyone to the enjoy the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health’ have expressed deep concern for North Korea’s ongoing human rights violations in their reports to the UN Human Rights Council. Furthermore, Special Rapporteur Vitit Muntarbhorn invited the international community to take measures to prevent egregious violations, protect people from victimizations, and provide effective redress. This is to be done by enabling the entirety of the UN system, especially the Security Council and affiliates such as the International Criminal Court, to take action in terms of state responsibility and/or individual criminal responsibility.8)

Recently, the International Criminal Court (ICC) accepted a lawsuit filed in December 2009 by a human rights group, the ‘Crimes against Humanity Investigation Committee,’ regarding North Korea’s treatment of its political prisoners.9) Furthermore, both South Korea and Japan have urged the ICC to investigate reports that North Korea abducted South Korean and Japanese citizens during the 1970s and 1980s for the purpose of training military spies. In law, the ICC may only prosecute those crimes occurring after its inception by the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court on July 1, 2002. Regarding South Korea and Japan’s grievances against North Korea, however, Vice President of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia Kwon O-gon stated that “it could be argued that the crimes are still in progress because the North has refused requests from South Korea and Japan to repatriate the abduction victims.”10)

Despite international efforts, North Korea has persistently denied the existence of its political detention camps and often reacts strongly to foreign criticism regarding human rights, making it difficult to address these problems. Though concrete evidence regarding North Korea’s humanitarian violations has been difficult to obtain, numerous governmental and nongovernmental organizations have documented the few reports that have become available. Based upon these documents, the case against North Korea concerning its ‘Responsibility to Protect’ leaves little doubt as to the reality of the state’s crimes against humanity, though the extent of its infractions remain difficult to pinpoint.

This article explores how the issue of mass atrocities in North Korea can be recognized by the international community as ‘crimes against humanity.’ Previous research has analyzed international legal options, asserting that the United Nations could launch an investigation into the DPRK’s abuses and refer the case to the ICC or a special tribunal. To pursue this, the UN Secretary-General should launch an investigation into the DPRK’s abuses to support a Security Council referral of the DPRK situation to the ICC. Or, if the investigators find it necessary to overcome the ICC’s temporal jurisdiction requirement, a special tribunal can be created to hear the case.11) However, the impact of such legal options is limited, as they lack a long-term plan to create enduring improvements within North Korea. My central argument, therefore, is that North Korean human rights should be dealt with through the ‘Responsibility to Protect’ doctrine, being established as an important instrument for assisting North Korea and as an internationally accepted norm for pursuing humanitarian intervention.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. First, the historical emergence of ‘crimes against humanity’ as a legal issue will be discussed, along with the debate between state sovereignty and international rights to intervene in domestic affairs. Second, North Korea’s human rights violations will be elaborated upon, legally defining them as ‘crimes against humanity.’ Last, the complex and evolving interrelation between North Korea and the international community will be examined in terms of the aforementioned Responsibility to Protect. This will look at North Korea’s efforts to improve its R2P and the international community’s ability to assist North Korea with this objective.

1)General Assembly, “Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Vitit Muntarbhorn,” A/HRC/13/47 (17 February 2010), p. 5. 2)Korea Institute for National Unification, White Paper on Human Rights in North Korea 2009 (Seoul: KINU, 2009), p. 14. 3)U.S. State Department, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, “2009 Human Rights Report: DPRK” (11 March 2010), p. 2, available at

Ⅱ. Crimes against Humanity: Historical Perspectives

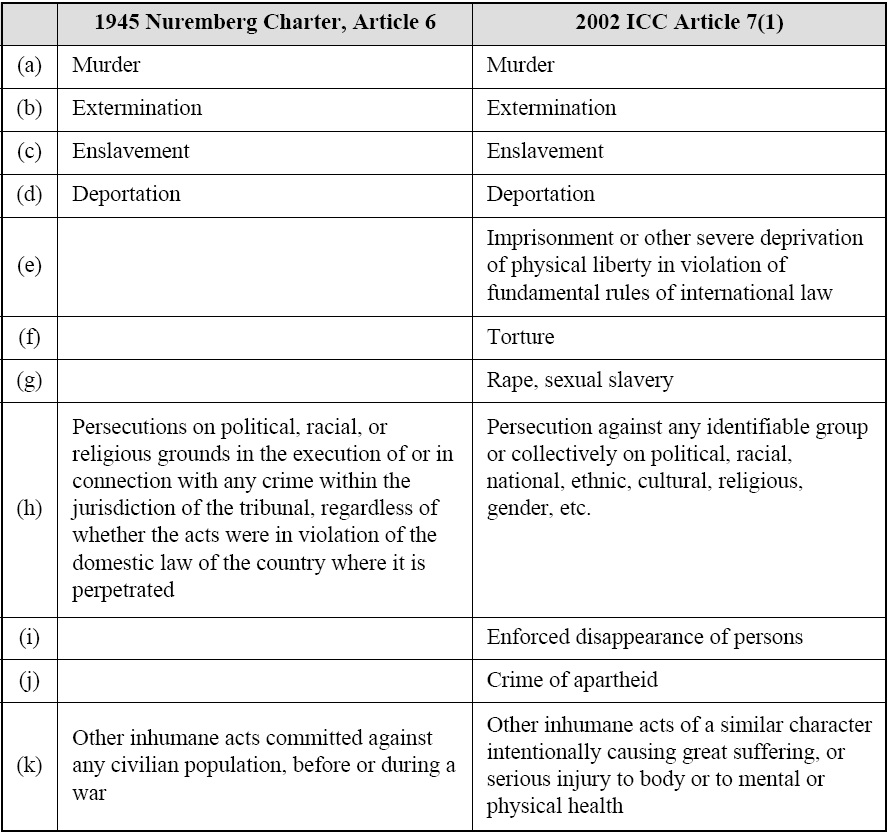

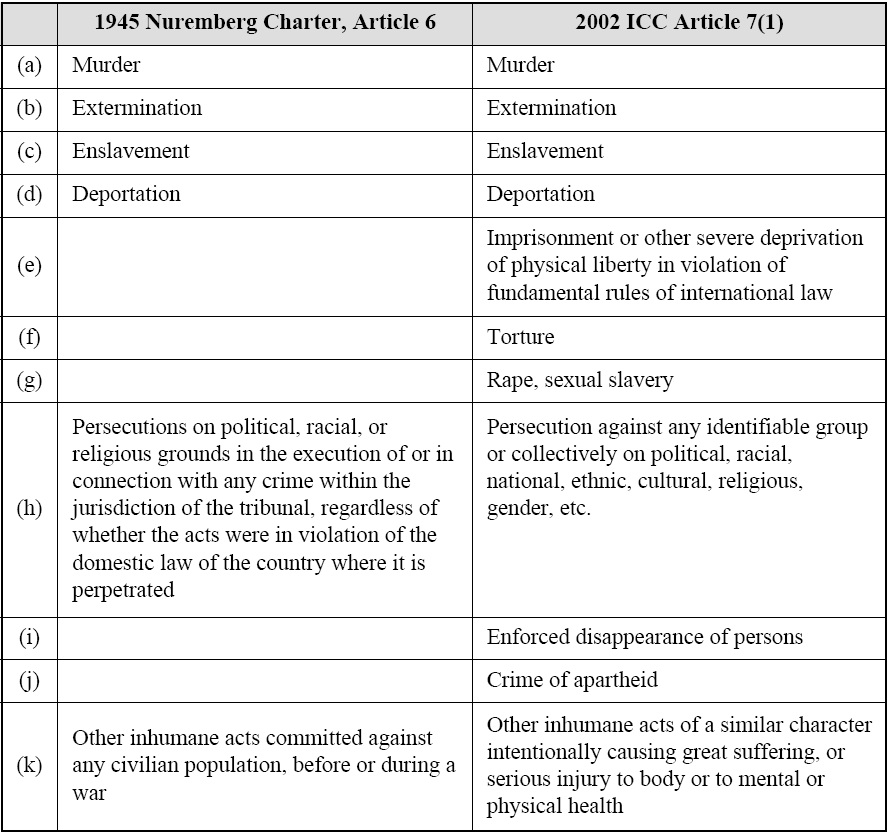

After the Second World War, the United Nations established a new crime called ‘crimes against humanity’ to punish inhumane acts committed by the German government against its own people and the citizens of other states for political and ethnic reasons. In August 1945, the international community defined ‘crimes against humanity’ as namely murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation, and other inhumane acts committed against any civilian population, before or during a war. The definition also included persecutions on political, racial, or religious grounds in the execution of or in connection with any crime within the jurisdiction of the tribunal, regardless of whether the acts were in violation of the domestic law of the country where it was perpetrated.12) In December 1946, the UN General Assembly unanimously adopted ‘crimes against humanity’ along with ‘crimes against peace’ to affirm that the international community hold itself responsible for such crimes.13) Later, in December 1949, the UN adopted the ‘Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide’ which was a landmark international agreement to stop genocide, one of the defined “crimes against humanity.”

Despite this normative development, the legal aspects of the treaty have not been consistently implemented as the international community has often remained quiet during outbreaks of such crimes. Since 1945, ‘crimes against humanity,’ and genocide in particular, have frequently occurred during periods of conflict as well as times of peace. The international community broke its silence, however, when crimes against humanity, genocide, and war crimes took place during the Balkans conflicts in the 1990s. In May 1993, the UN Security Council established the ‘International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia’ (ICTY) under Article 7 of the UN Charter.14) Consequently in November 1994, the ‘International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda’ (ICTR) was established15) to punish the humanitarian violations committed during Rwanda’s civil war.

In July 1998, the international community adopted the Rome Statute, which entered into force in July 2002, after its ratification by sixty countries. The Rome Statute formed the legal basis for establishing the independent and permanent International Criminal Court (ICC).16) Under Article 7(1) of the ICC, the acts constituting ‘crimes against humanity’ were expanded from the 1945 definition.17)

[Table 1.] Definition of Crimes against Humanity: 1945 and 2002

Definition of Crimes against Humanity: 1945 and 2002

12)Article 6 of the Charter of the International Military Tribunal (“Nuremberg Charter”), annexed to the Agreement for the Prosecution and Punishment of Major War Criminals of the European Axis (“London Agreement”). 13)United Nations General Assembly Resolution 95 (1946), UN Document A/64/Add. 1. 14)UN Security Council Resolution 827 (1993), UN Document S/RES/827, available at

Ⅲ. Sovereignty vs. Human Rights: Theoretical Perspectives

State sovereignty has been the defining principle of interstate relations since the Treaty of Westphalia in 1968. The concept of state sovereignty, which lies at the heart of both customary international law and the United Nations Charter, has been unchallenged either in law or in practice, as a formal legal definition. Sovereignty, as understood through the Westphalian model, is based on two principles: territoriality, and the exclusion of external actors from domestic authority structures.18) The fundamental norm of Westphalian sovereignty is that states exist in specific territories, within which domestic political authorities are the sole arbiters of legitimate behavior. The rule of nonintervention is the key element of sovereign statehood, of which weaker states have been among the strongest supporters.19) With the Treaty of Westphalia endorsing supreme territorial authority under the principle of sovereign nonintervention, human rights had been regarded as the exclusive domain of the individual nation-state.

This fundamentally changed in 1945, when the UN Charter and its provisions accepted limits to state sovereignty and domestic jurisdiction in international law.20) First, as recognized in the UN Charter of 1945, the sovereignty of states must yield to the demands of international peace and security.21) Second, state sovereignty may be limited by customary and treaty obligations in international relations and law. States are legally responsible for the performance of their international obligations, and therefore state sovereignty cannot be used an excuse for their non-performance.22) In line with this view of sovereignty, the duty to prevent and halt ‘crimes against humanity’ lies first with the state, but the international community has a role that cannot be blocked by the invocation of sovereignty. The principle that sovereignty no longer protects states from foreign intervention, under specifically defined circumstances, is enshrined in the concept of Responsibility to Protect.23) The biggest question regarding humanitarian intervention, therefore, is who should undertake humanitarian intervention and when is it justifiable to do so.

In the 2000 Millennium Summit report, the UN Secretary-General revisited the question of intervention and challenged UN delegates to resolve the perceived tensions between sovereignty and human rights by proposing an ‘International Commission on Humanitarian Intervention.’24) The resulting ‘International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty (ICISS)’s report,

Furthermore, the concept of “sovereignty as responsibility” is reflected in the commitment of member states in the ‘Responsibility to Protect’ principles adopted in the 2005 UN General Assembly World Summit Outcome Document (paragraphs 138-139) and later reaffirmed a UN resolution in September 2009.25) Member states agreed that there exists a universal ‘responsibility to protect’ populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity. On the surface, this agreement was something of a watershed moment for humanitarian intervention.26) Following the United Nations World Summit of 2005, the member states reaffirmed a collective responsibility to protect innocent civilians in the face of repressive or deliberately negligent government behavior.

18)According to Stephen D. Krasner, the term sovereignty has been commonly used in at least four different ways: domestic sovereignty, referring to the organization of public authority within a state and to the level of effective control exercised by those holding authority: interdependence sovereignty, referring to the ability of public authorities to control transborder movements; international legal sovereignty, referring to the mutual recognition of states or other entities; and Westphalian sovereignty, referring to the exclusion of external actors from domestic authority configurations. Stephen D. Krasner, Sovereignty: Organized Hypocrisy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999), pp. 9-25. I will focus on Westphalian sovereignty. 19)The principle of nonintervention was first explicitly articulated by Wolff and Vattel in 1760. Wolff wrote that “to interfere in the government of another, in whatever way indeed that may be done is opposed to the natural liberty of other nations in its action.” Also Vattel argued that no state had the right to intervene in the internal affairs of other States. Ibid., pp. 20-21. 20)David P. Forsythe, The Internationalization of Human Rights (MA: Lexington Books, 1991), pp. 14-15. 21)According to Chapter 7 of the UN Charter, sovereignty is not a barrier to action taken by the Security Council as part of measures in response to “a threat to the peace, a breach of the peace or an act of aggression.” 22)According to Article 55 of the UN Charter, the United Nations shall promote observance of human rights and fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion. 23)United Nations, Office of the Special Advisor on the Prevention of Genocide, available at

Ⅳ. Responsibility to Protect and North Korea

While the primary aim of ‘Responsibility to Protect’ is to prevent human rights abuses, a secondary purpose is to prevent the misuse of military or humanitarian intervention in three ways. First, understanding R2P as a broad framework with preventive and reactive measures, military intervention can be allowed only when a state has manifestly failed to protect its populations and when peaceful means have proven inadequate. Second, intervention under R2P must specifically protect populations from the four stated types of mass atrocities. Third, as agreed to in 2005, R2P legitimizes the use of force only if it is employed collectively through the UN Security Council. However, while governments and civil society are rightfully concerned about the misuse of military force, experience has demonstrated that the greatest danger is not that the international community will intervene improperly, but that they will not act at all in the face of humanitarian atrocities.27)

‘Responsibility to Protect’ focuses on four categorical crimes: crimes against humanity, genocide, ethnic cleansing, and war crimes, calling for their prevention through appropriate and necessary means. The participating states of the 2005 World Summit accepted this “responsibility and will act in accordance with it,” further stating that “the international community should, as appropriate, encourage and help states to exercise this responsibility and support the United Nations in establishing an early warning capability.”28) As such, R2P is built upon the following three pillars: (a) the enduring responsibility of a state to protect its populations; (b) the commitment of the international community to assist states in meeting those obligations; and (c) the responsibility of UN Member States to respond collectively, in a timely and decisive manner, when a state is manifestly failing to provide such protection.29)

Under such a definition, prevention, building upon the first two pillars, remains the key ingredient for a successful strategy under R2P. It is important to note that R2P does not simply call for the use of reactive or coercive tools to enforce its provisions. Rather, the principle emphasizes the primacy of preventive efforts and capacity building through multilateral support measures.30) It includes the use of military force by the international community only as a last resort, and only if peaceful measures prove inadequate.31)

1. North Korean Human Rights Violations

North Korea is now at a critical juncture regarding its human rights practices, as it faces a humanitarian disaster that may legally be categorized under “crimes against humanity.” However, identifying North Korea’s human rights violations presents an ongoing challenge for the international community. The strict security policy of the Kim Jong-il regime, including control over both international and domestic flows of information, makes it difficult to collect evidence that could be used in a legal proceeding. Much of the evidence that has been gathered has relied on statements from North Korean defectors or reports gathered through human rights NGOs. This has provided a basic understanding of North Korea’s human rights violations, but specific and concrete evidence has been lacking.

North Korea has long been regarded as having one of the world’s worst human rights records, with the most glaring instances being the state’s political detention camps. Showing the extent of the problem, a 2010 report indicated that North Korea currently holds some 200,000 political prisoners in six large camps across the country.32) After North Korea’s liberation from Japan, political detention camps were initially operated as ‘special labor camps.’ Then, with the introduction of the Soviet-style gulag system, political detention camps began to take on their current form. Following the

Reports by the United Nations and several NGOs have highlighted the deplorable conditions in which North Korea’s political prisoners are confined, including widespread malnutrition, hard physical labor, and forced abortions. In particular, refugees who are forcefully repatriated often face arbitrary detention, interrogation by torture, inhumane and humiliating treatment, sexual abuse, infanticide, and execution within the labor camps.34) Moreover, the legal process through which North Koreans are accused, tried, and sentenced lacks transparency and due process in accordance with universal standards of human rights.35) Citizens who are accused of political dissent lack legal protection, such as being presented with a warrant and being explained the reason for their arrest. They also do not receive fair and orderly trials, often being left to the discretion of the State Security Department or other state organizations. The main reasons for arrest include accusations of political criticism, defection to South Korea, anti-government activities, and the guilt-by-association system, but most prisoners do not know the reasons for which they are confined. This lack of basic legal rights, lack of judicial due process, and the severity of the country’s penal system has given North Korea one of the world’s worst human rights records.

2. Justifying the North Korea Case as ‘Crimes against Humanity’

The case against the political prison camp system can be divided into two categories of violations: violations inside the camps and violations during sentencing and deportation.

1) Violations Inside the Camps

Numerous types of crimes against humanity are committed inside North Korea’s political prison camps. Under Article 7(1) of the ICC, (a) murder, (b) extermination, (c) enslavement, (f) torture, (g) rape, sexual slavery, (k) other inhumane acts of a similar character intentionally causing great suffering or serious injury to body or to mental or physical health, (h) persecution against any identifiable group or collectively on political, racial, national, ethnic, cultural, religious, gender etc., and (i) enforced disappearance of persons are all crimes within the court’s jurisdiction. Each of these crimes is frequently committed in North Korean detention camps.

The United States Congress has cited evidence that North Korea regularly executes political prisoners at public meetings attended by workers, students, and schoolchildren. North Korea’s State Security Agency is reported to run the political detention camps through the use of forced labor, beatings, torture, and executions. Conditions in which many prisoners die from disease, starvation, and exposure are also common. According to eyewitness testimony provided to the U.S. Congress by North Korean camp survivors, camp inmates have been used as sources of slave labor for the production of export goods, as targets for martial arts practice, and as experimental subjects in the testing of chemical and biological poisons. Furthermore, according to credible reports, including eyewitness testimony, North Korean Government officials prohibit live births in prison camps, with forced abortion and infanticide being standard prison practices.36) The UN Security Council, in resolutions 1612 (2005) and 1820 (2008),37) underscored that rape and other forms of sexual violence could also constitute ‘crimes against humanity.’38)

2) Violations during the Sentencing and Deportation Process

Crimes against humanity are also frequently committed during sentencing and deportation procedures. Under Article 7(1) of the ICC, (d) deportation or forcible transfer of populations, (e) imprisonment or other severe deprivation of physical liberty in violation of fundamental rules of international law and (i) enforced disappearance of persons are considered crimes against humanity. Each one has been committed against political prisoners during the deportation process to North Korea’s detention camps. The North Korean government forcibly transfers large numbers of individuals to political prison camps in other parts of the country as a means of punishment. While illegal residence is often cited as a reason for forced eviction in non-punitive cases, those transferred to prison camps are typically legal residents of the locations from where they are taken.39) Also the prisoners are incarcerated in political prison camps without being granted judicial safeguards and without having faced fair and legal trials as recognized by applicable international standards. Based on this, the system of arresting, transferring, and imprisoning political prisoners clearly violates the human rights of North Korean citizens.40)

27)Marion Arnaud, “The Responsibility to Protect: A New Norm for Preventing and Halting Mass Atrocities,” International Coalition for the Responsibility to Protect, 24 November 2010, p. 1, available at

North Korea’s argument against R2P is that non-interference in domestic affairs, as stipulated in the UN Charter, is not respected. North Korea also insists that R2P is, in effect, a license for the powerful to intervene unilaterally in another country, believing that R2P may be used to justify foreign interference in small and weak countries. This is because North Korea holds that human rights are inseparable from national sovereignty, arguing that human rights are guaranteed only within sovereign states. According to North Korea’s perspective, therefore, there are three components which constitute violations of human rights: any attempt to interfere in another’s internal affairs, the overthrow of a government, and the forced change of a country’s systems on the pretext of human rights issues.41)

1. Referring the Case to the International Criminal Court (ICC)

In case of North Korea, the international community’s response has fallen short. Prior United Nations actions against states deemed to be human rights violators have included economic sanctions and peacekeeping intervention.42) North Korea is already under extensive international sanctions and the absence of internal conflict makes direct intervention an unviable option in terms of international law and precedence.

To improve the situation, legal action must be brought against the perpetrators of North Korea’s human rights violations, including Kim Jong-il and his cadres. This requires the UN Security Council to refer the North Korea case to the ICC43) or, if necessary, overcome the ICC’s temporal jurisdiction requirement and create a special tribunal to open an investigation and possible prosecution. One of the weaknesses of the ICC and the UN Security Council, however, is that these international bodies lack independent authority to enforce their decisions. Often, target countries refuse to accept the results of a verdict or resolution, and the provision of foreign assistance and UN-sanctioned intervention depends upon the participation of other sovereign states.

Efforts to punish North Korean violators of human rights through ICC hearings also have their limits. Eight trials are currently underway at the court, all arising out of civil wars in Africa. The court has yet to convict a defendant in any of these offenses, and has never prosecuted a case arising out of a conflict between states. This indicates that the ICC has yet to fulfill its intended role of ensuring the protection of human rights through international law. Even for cases that had been fully prosecuted through the ICC, offenders have often died before receiving their sentence, such as with Slobodan Milosevic. Thus, the role of the ICC should be broadened to meet the requirements of ‘Responsibility to Protect,’ and to effectively establish a legal precedence for addressing humanitarian violations in a timely manner.

2. Assisting North Korea’s Sovereignty

In accordance with R2P, the international community should assist North Korea in fulfilling its responsibilities of sovereignty and increasing efforts to protect its citizens. ‘Responsibility to Protect’44) focuses on the conditions of the victims, and insists that the primary responsibility for protecting citizens from mass atrocity crimes lies with the state itself.45) In the perspective of R2P, state sovereignty, specifically the monopoly of violence, implies a commitment to the welfare of the people rather than a license to kill.46)

In order to avoid ICC prosecution and possible intervention, North Korea should reinforce its traditional sovereignty by taking responsibility to protect its citizens. Because R2P’s primary tools are persuasion and support, rather than military action or other forms of coercion, cooperation with North Korean leaders should be encouraged.47) Rather than working against the regime, effort should be made to provide assistance in improving North Korea’s own capacity to protect its people from crimes against humanity, as a way to promote change while affirming North Korea’s sovereignty.

In this sense, the most effective way to improve North Korean human rights conditions would be for the international community to work with North Korea instead of positioning against the regime. To do this, the international community should show their concern by increasing its awareness of North Korea’s human rights issues, and framing the solution in a way that would enable North Korea’s formal participation. Then, the international community and North Korea could begin working together to gradually improve North Korea’s human rights situation. This would start from the easiest and most agreeable topics such as judicial reform and rewriting the legal code, and move toward more difficult agenda items such as the political detention camps and legal administrative structure.

Also a more amiable method of assistance would need to be pursued that simultaneously seeks to protect North Korean citizens while reaffirming North Korea’s right to sovereignty. This would address the domestic security concerns of the regime and allow North Korea to accept step-by-step solutions to make its own necessary changes. Even if Pyongyang does not allow other countries to be directly involved in domestic human rights matters, it would still be necessary for the international community to promote these changes without challenging the regime itself. This would require a gradual process of domestically initiated transformation rather than an abrupt or externally induced transition. As has often been the case in dealing with North Korea, any threats to the stability of the regime are actively avoided.

However, if North Korea proves unwilling or unable to avert these mass atrocity crimes, then R2P states that the international community has the collective responsibility to take the necessary actions to protect those citizens under duress.48) In such a case, the international community and intergovernmental bodies can play pivotal roles in conducting on-site investigations and fact-finding missions. Investigations can provide opportunities to send important signals to North Korea, such as dissuading Pyongyang from destructive courses of action that could make them subject to prosecution by the International Criminal Court (ICC) or special tribunals.49)

41)UN Human Rights Council, “National Report Submitted in Accordance with Paragraph 15(A) of the Annex to Human Rights Council Resolution 5/1: Democratic People’s Republic of Korea,” A/HRC/WG.6/6/PRK/1 (27 August 2009), p. 4. 42)Paolo Camarotta, Joe Crace, Kim Worly, and Haim Zaltzman, “Legal Strategies for Protecting Human Rights in North Korea,” Skadden, Arps, Slade, Meagher & Flom LLP and U.S. Committee for Human Rights in North Korea (28 November 2007), pp. 39-45. 43)The ICC was established to be a standing international mechanism to prosecute war crimes, genocide, crimes against humanity, and crimes of aggression. Currently the jurisdiction of the ICC covers three out of four of the specified mass atrocity crimes (excluding ethnic cleansing) of R2P criteria. 44)The Responsibility to Protect essentially rests on the following three pillars: (a) the enduring responsibility of a state to protect its populations; (b) the commitment of the international community to assist states in meeting those obligations; (c) the responsibility of UN Member States to respond collectively in a timely and decisive manner when a states is manifestly failing to provide such protection. 45)Alex J. Bellamy, Responsibility to Protect: The Global Effort to End Mass Atrocities (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2009), pp. 44-45. 46)2005 World Summit Outcome Document, para. 138, 139. UN Document A/RES/60/1. 47)See Crisis Group at

Although the international community affirmed its responsibility to avert ‘crimes against humanity’ in 1946, it has rarely responded in a timely and appropriate manner. Not until the outbreak of such atrocities as genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity during the Balkans conflicts in the 1990s did the international community break its silence on the issue. However, this response prompted strong debate between proponents of humanitarian intervention and non-interventionists who hold state sovereignty as inviolable. The international community then received strong criticism regarding the Rwanda genocide and Sudan’s Darfur massacre, having failed to respond in any concrete manner. Finally, at the 2005 World Summit, the international community declared that each individual state has the ‘Responsibility to Protect’ its population from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity. Furthermore, the international community declared that it should, as appropriate, encourage and help states to exercise this responsibility and support the United Nations in establishing an early warning capability.

By recognizing the mass atrocities in North Korea as ‘crimes against humanity,’ the international community can address North Korea’s human rights problem from the perspective of the ‘Responsibility to Protect’ doctrine. North Korea’s human rights violations have been elaborated and verified, focusing primarily on violations inside political detention camps and violations during the sentencing and deportation process, constituting nine out of eleven ‘crimes against humanity’ outlined in Article 7(1) of the ICC. Within the complex and evolving relationship between North Korea and the international community, the international community can assist North Korea to improve its human rights conditions by invoking an R2P approach.

In contrast to current criticism of the ‘Responsibility to Protect’ principle, R2P focuses on protecting victims rather than punishing perpetrators. R2P insists that the primary responsibility for protecting citizens from mass atrocity crimes lies within the state itself, with the primary methods of enforcement being persuasion and support rather than military forms of coercion. There needs to be effective tools, therefore, to provide assistance and improve North Korea’s own responsibility to protect its people from crimes against humanity, by encouraging cooperation with the regime rather than working against it.

In this sense, the international community and North Korea should begin working together to gradually improve North Korea’s human rights situation, starting from the easiest and most agreeable topics such as the judicial reform, before addressing more difficult agenda items such as political detention camps. Also, there needs to be a proactive method of assistance that would address the domestic security concerns of the regime. This would allow North Korea to accept step-by-step solutions to make its own necessary changes, even if the regime does not allow other countries to become directly involved in the human rights matter.

If North Korea becomes unwilling or unable to avert the occurrence of these mass atrocity crimes, then R2P could be initiated through international action, such as urging on-site investigations and fact-finding missions. This can provide opportunities to deliver messages directly to North Korea and dissuade the regime from destructive courses of action that could make it subject to prosecution by the International Criminal Court. Pyongyang may see the recent intervention in Libya as a reminder that sovereignty entails responsibility. If this new sovereignty principle is not implemented by the state itself, the international community may then declare the right to intervene.