Directed by Kim Chiun, the Korean film,

The film,

The film opens in a mental ward. Clad in hospital garb, Sumi comes in with a nurse as a doctor sits across from her. Although the doctor asks Sumi questions, she does not respond in any way or form. When the doctor shows Sumi a photo of her family and once again asks her about what happened on ‘that day’, Sumi turns her head and can be seen immersed in thought. This scene is reminiscent of the intro to the film

By the mid-part of this film, viewers have already begun to suspect that, much as was the case in the

The latter part of the film features methods, such as scenes that make viewers wonder ‘Why?’ that were first used in Alfred Hitchcock’s

As such, the director Kim Chiun employed horror film formats, contents and genres that he was cognizant of to construct the narrative of

The classic novel

Briefly put, Kim Chiun’s

1I will first begin by delving into this assertion in a more in-depth manner in order to establish the clear differences between these two. This constitutes a very important premise of this study. 2Sim Yŏngsŏp, “Changhwa Hongnyŏn (A Tale of Two Sisters) is more focused on Sumi’s legs than her internal world (Sumi ŭi naemyŏn taesin tari e t΄amnik hanŭn Changhwa Hongnyŏn)”, Cine 21, Issue No. 409, July 7, 2003. 3The novel, Changhwa Hongny?n ch?n (Story of Changhwa Hongny?n) is classified as a so-called ‘Arang’ type of classic novel, a category that also includes such works as Kim Inhyang ch?n (Story of Kim Inhyang) and Suky?ng Nangja ch?n (Story of Suky?ng). The story of Arang revolves around a girl who dies after an attempt is unsuccessfully made to rape her. Thereafter, she becomes a ghost who routinely appears before the local governor to implore him to avenge her. Paek Munim, “Study of Korean Horror Films?With a special focus on the narratives of female ghosts (Han’guk kongp’o y?nghwa y?n?gu?y?gwi ?i s?sa kiban ?l chungsim ?ro)”, Ph.D. dissertation, Yonsei University, 2002.

2. REVIEW OF PREVIOUS WORKS AND ANALYSIS OF ISSUES

Let us begin by analyzing some of the basic premises associated with the film,

An attempt is made herein to examine in a chronological manner, beginning right after the release of

First, Yu Unsŏng regarded this film as having in effect abandoned the original nature of the classic novel. Yu asserted that contrary to the original novel, this film sought to highlight the sense of guilt that led to the appearance of the vengeful spirit; the fact that this sense of guilt was nothing more than an imaginary force created by a masochistic entity; and that the vengeful spirit was in essence an illusion that emanated from this imagination.

While the sense of guilt is essentially the result of the imagination of a masochistic entity, the vengeful spirit is nothing but an illusion that emanates from this imagination. In other words, although the vengeful spirit does not dream of revenge, the sense of guilt ‘fervently’ summons the vengeful spirit… In conclusion, Kim Chiun’s third feature film

Yi Hyoin viewed

However, Chŏng Sŏngil proved to be the most severe critic of this film in terms of any comparison between it and the original classic novel.

Ch?ng S?ngil’s piece leaves no doubt as to his belief that this film is a strange one. The reasons for this assessment are very clear. The expectations which the author had before seeing the movie can be found in the introductory section of this piece and until the part from which the quote above appears; to this end, it is evident that the author’s perusal of this film was skewed by his own transcendental experiences. As a result, Ch?ng was looking forward to seeing how Kim Chiun would give a modern twist to the contents of the original classic novel. However, his expectations were dashed. This misinterpretation of the film, which is caused by the fact that Ch?ng S?ngil’s premises were based on the story found in the original classic novel, continues unabated. A counter-argument to this stance will be introduced in the latter part of this study.

Of the various film critics which have assessed this work, ‘DJUNA’ can be regarded as the one whose position concerning the relationship between the film and the original novel most closely mirrors the one advanced by the author of the present study. DJUNA clearly states his position by stressing that the role of the original novel in the film can be compared to the handkerchief which a magician shakes in order to deceive the audience.

However, Sim Y?ngs?p bitterly criticized this film for not only having failed to provide the vividness of the various abundant virtues on display in the original classic novel, but also for having limited itself to the autistic fantasy of singling out one classic and conservative ideology, one that constitutes the most anachronistic of the ideologies found in the original classic novel, and lumbering with it all the way through the film.

Let us now look at the work carried out by academic researchers. Here, it is interesting to note that the methods used to express the authors’ opinions about the relationship between the text of the film and original classic novel are heavily dependent on their particular field of study. Let us begin by quoting Hwang Hyejin, who published two studies and a critique on the subject of the film

The understanding evident in the above quotation is also clearly on display in Hwang Hyejin’s other piece (study). Hwang argues that the classic novel and the film share many similarities and differences, including the death from illness/suicide of the mother, and the murder/accidental death of Hongnyŏn (Suyŏn). Perhaps it is Hwang’s status as a film researcher that allows her to draw a simple line to demarcate the relationship between the film and original classic novel. On the contrary, the opinions of the researchers in the field of literature, some of which will be quoted below, are serious to the point of being a cause for concern. The most representative of these assertions are those of Yi Chŏngwŏn and Cho Hyŏnsŏl. Let us first take a look at Yi Chŏngwŏn’s study. Citing the reviews written by the likes of Yu Unsŏng, Yi Hyoin, Chŏng Sŭnghun and Sim Yŏnsŏp in the magazine

Meanwhile, Cho Hyŏnsŏl’s study can be regarded as the final word in terms of the comparison of the two texts, and of the close relationship that exists between the film and classic novel. Viewing film as a sub-genre of novel literature, Cho asserted that the film

Such assertions appear to paint a self-seeking portrait. However, although paradoxical, this in fact represents the core of the strategy in terms of what use the director Kim Chiun sought to make of the original classic novel

2-2) Disputes concerning the completeness of the story

When the film

This film’s scenario does have some serious flaws that need to be pointed out. These include temporality, cause and effect, and the logic of the narration and points of view. A look at the scenes which were cut during the editing process reveals that Kim continuously worried about and searched for solutions to some of these elements. However, the viewers can only watch the ‘completed’ work which unfolds on the screen after it has left the director’s hands. In other words, the viewers have no choice but to judge the film based on the ‘completed’ work. The attributes of the horror film genre make it possible for audiences to forgive the problems occasioned by the ambiguousness of the narrative, and lack or excessiveness of some details.14 Rather, the insecurity caused by such ambiguous narratives amongst audiences can be regarded as one of the biggest tools which directors have at their disposal when it comes to creating horror. Director Kim Chiun’s active use of this element is clearly exposed in the following passage from an opinion piece.

The above statement shows where the director obtained the behavioral patterns that constitute the core of Sumi’s character, and how he made up the story for the film. In fact, in his role as storyteller in the horror genre, the director does not need to know about the actual truth of all the events and incidents that unfold in the story. Even if he knows all the details of the story, the filmmaker does not have to show them all, or include explanations within the story structure. The main objective for the director (storyteller) is that of finding ways to use the elements that he is cognizant of, or possesses, to control the audience.

The narrative (or drama) of this film is clearly very unique and strange. As Sim Yŏngsŏp harshly points out, in a manner akin to Chŏng Sŏngil, this film can be regarded as a violation, genre deviation, and attempt to catch the audience unaware.16 However, in my opinion, that is not the case. At the core of the film’s narrative is the story of a girl named Sumi who single-handedly produces and brings to life the story of

Through a reorganization of the story of this film and analysis of the narrative structure, an attempt is made below to substantiate the logic of the issues raised by numerous people who have commented on this film. Although Kim Chiun released one film, disputants have exhibited polar opposite perceptions and degrees of acceptance of this work. In this regard, the claim advanced in the field of contemporary semiotics proposed by the likes of Umberto Eco and the cognitive film theory represented by David Bordwell to the effect that ‘the perfector of texts is not the writer but the acceptor’ can be regarded as being particularly applicable. While an in-depth comparison is not possible in the space provided herein, 17 the differences in terms of how individual viewers perceive the film can nevertheless be ascertained by looking at their synopses of the film. To this end, this study will reorganize the film’s story and break the text down into individual segments for analysis.

4Yu Unsŏng, “The genre imagination of the director of Changhwa Hongnyŏn (Kamdok ŭi changrŭ chŏk sangsangnyŏk, Changhwa Hongnyŏn)”, Cine 21, Issue No. 406 (June 10, 2003). 5Yi Hyoin, “Changhwa Hongnyŏn is in no way related to the classic novel of the same name. It is nothing more than a violation thereof! (Changhwa Hongnyŏn chŏllae tonghwawanŭn amu sanggwan ŏmne! panch΄ikida)”, Cine 21, Issue No. 408, July 1, 2003. 6Chŏng Sŏngil, “A strange and insecure anti-feminist film (Kiyi hago pulanhan pan feminist yŏnghwa)”, monthly magazine Mal, July 2003, p. 205. 7DJUNA (film critic, SF novelist), “Changhwa Hongnyŏn is interesting but fails to fill the holes in the latter part of the film (Hŭngmiropchiman hubanbu ŭi pint’ŭm ŭl ch’aeuji mothan Changhwa, Hongnyŏn)”, Cine 21, Issue No. 408, July 1 2003. 8Sim Yŏngsŏp, ibid. 9Hwang Hyejin, “A study of the family narrative exhibited in horror films—with a special focus on the memories in Changhwa Hongnyŏn and 4 inyong sikt΄ak (The Uninvited) (Kongp΄o yŏnghwa e nat’anan kajok sŏsa yŏn΄gu—Changhwa Hongnyŏn kwa 4 inyong sikt’ak e nat΄anan kiŏk ŭi munje rŭl chungsim ŭro)”, Yŏnghwa yŏn΄gu (Journal of Film Studies), Vol. 29, Film Studies Association of Korea, 2000, pp. 381–382. 10Yi Chŏngwŏn, “The memory and reality of women in the film, Changhwa Hongnyŏn and the actuality thereof—as viewed from the standpoint of the classic novel, Changhwa Hongnyŏng chŏn (Yŏnghwa Changhwa Hongnyŏn esŏ yŏsŏng taehan kiŏk kwa silje—kososŏl Changhwa Hongnyŏng chŏn yi pon yŏn’gu kwanjŏm esŏ)”, Han’guk kojŏn yŏsŏng munhak yŏn’gu (Journal of Korean classic woman’s literature), Vol. 15, pp. 74–75. 11Cho Hyŏnsŏl, “The future tasks in the study of classic novels as viewed through the cinematographic adaptation of classic novels—With a special focus on the classic novel, Changhwa Hongnyŏn chŏn and the film, Changhwa Hongnyŏn (Kososŏl ŭi yŏnghwahwa chakŏp ŭl t’onghae pon kososŏl yŏn’gu ŭi kwaje—kososŏl Changhwa Hongnyŏn chŏn kwa yŏnghwa Changhwa Hongnyŏn)”, Journal of Classic Novel Studies (Kososŏl yŏn’gu), Vol. 17, The Old Novel Society of Korea, 2004, p. 61. 12Chŏng Sŏngil, ibid., p. 206. 13Chŏng Sŭnghun, “Although it fails to overcome the physical science aspect of horror, Changhwa Hongnyŏn is a work one cannot avert one’s eyes from” (Kongp΄o ŭi hyŏngyihahak ŭl nŏmji mothaetchiman nun ŭl ttelsu ŏmnŭn yŏnghwa, Changhwa Hongnyŏn)”, Cine 21, Issue No. 408, July 1, 2003. 14The horror film genre is not one which promotes moderation. What criticism can be leveled as long as excessiveness plays its rightful role in such works? DJUNA (film critic, SF novelist), “The challenge posed in 2003 by Korean horror films to ‘art’—A semi-success or simply a process of trial and error? (2003 Han΄guk horror ŭi ‘yesul’ tojŏn—chŏlban ŭi sŏnggong hokŭn sihaeng ch’akoe taehayŏ)”, Cine 21, Issue No. 417, August 29, 2003. 15Kim Hyeri, “The horror of Changhwa Hongnyŏn: Kim Chiun Vs. Yun Chongch΄an (Changhwa Hongnyŏn ŭi kongp’o: Kim Chiun Vs Yun Chongch’an)”, Cine 21, Issue No. 407, June 17, 2003. 16Stuck in a multi-layered story and fantastic maze, the film Changhwa Hongnyŏn repeatedly dashes and rushes this way and that. The spirit is endowed with a human nature and viewpoint; another dream exists beyond the dream; another spirit exists within the spirit; another illusion exists within the illusion. This is closer in nature to a genre deviation that is filled with violations and tricks than a genre reversal that goes beyond the otherness and ego. This is clearly an attempt to catch the audience unaware (Sim Yŏngsŏp, ibid.). 17Clear differences can be seen when comparing the synopses prepared by Yi Chŏngwŏn and Hwang Hyejin. Yi Chŏngwŏn’s analysis of the film Changhwa Hongnyŏn is based on three premises, the first being that “the story unfolds in a cyclical manner” (Yi Chŏngwŏn, ibid., p. 77). This can be taken to mean that the events presented in the film do not run contrary to the temporal order. Although Yi tries to introduce proof to support this assertion, its validity remains hard to sustain.

3. REORGANIZATION OF THE SYNOPSIS AND ANALYSIS OF THE NARRATIVE STRUCTURE

3-1) Reorganization of the synopsis

The story that unfolds in this film can be reorganized in the following chronological manner.

A Japanese-style wooden house stands near a lake in the countryside. This house was originally inhabited by a family which consisted of a father (Muhyŏn), mother, and two sisters named Sumi and Suyŏn. However, when the illness of the mother takes a turn for the worse, the father, a pharmacist in a large-scale hospital, brings Ŭnju, a nurse who works at the same hospital, to their home to care for their mother (pictures). During this process, the father and Ŭnju begin to have an affair. Soon, Ŭnju starts to behave like she is the lady of the household, even going as far as to invite her brother and his wife to visit her. Sumi and Suyŏn are consumed by a strong sense of hostility toward Ŭnju. On the day when Ŭnju invites her brother and his wife over for dinner, Sumi begins to quarrel with Ŭnju during dinner and leaves in a huff. Ŭnju responds by taking away Suyŏn’s spoon. Suyŏn goes up to her room and cries herself to sleep while lying next to her mother. The mother subsequently commits suicide by strangulation in Suyŏn’s wardrobe, only to be discovered by the latter. Suyŏn screeches as she shakes her mother’s body in an attempt to revive her; when the wardrobe falls as a result of her shaking she finds herself pinned down under it. Upon hearing Suyŏn’s screeching, Ŭnju goes out to help, only to be verbally assailed by Sumi, all of which results in delaying her ability to get to Suyŏn to help her. Sumi darts out, but not before making snide remarks at Ŭnju who watches her with disdain as she exits. Unfortunately, Suyŏn dies as this exchange unfolds. After a prolonged period of institutionalization in a mental facility, Sumi returns to the house to live with her father. However, Sumi, who by now believes she is also Ŭnju, is under the illusion that Suyŏn, who has already died, is alive and living with her. Sumi’s internal turmoil has only increased since her return home. (The film opens with Muhyŏn arriving at the house along with Sumi and Suyŏn [in fact, there is only Sumi]. The two sisters run to the lake and enjoy their day splashing in the water. When they return home, their stepmother Ŭnju is there to welcome them. However, the sisters show great hostility toward Ŭnju. Strange things begin to occur in the house after the sisters come back. Someone sneaks into Suyŏn’s room. Sumi sees the spirit of her dead mother who died from strangulation. In the meantime, the conflict between the two sisters and Ŭnju becomes more acute to the point where Ŭnju places a large bag over Suyŏn’s head and begins to beat her. Upon returning from an outing, Sumi uncovers the bloodied bag in Suyŏn’s wardrobe and begins to fight with Ŭnju. Sumi loses consciousness after getting hit by Ŭnju with a bronze statue. However, it is revealed that all of these events in fact were caused by Sumi, who suffers from multiple personality disorder.) After Sumi injures herself (by hitting herself with a bronze statue), Muhyŏn asks Ŭnju for help. Sumi is sent back to the mental facility.

3-2) Analysis of the narrative structure

Here, it is necessary to take a good look at the situations created by Sumi’s illusions (Scenes 2–113). First of all, Scenes 2–10 belong to the film’s introductory section. Sumi, Suyŏn, the father (Muhyŏn) and stepmother (Ŭnju) are introduced, and the foundation for the two sisters’ future tensions is established. The inside of the house is filled with an unseen horror. Soon the war of nerves between Ŭnju and the two sisters starts. The insert scene used to show a panoramic view of the house (night time) ends the introductory part and leads to a new situation.

The situations found in Scenes 12 through 77 make up the middle part of the film. All the family members, except Muhy?n, see spirits and Sumi and Suy?n suffer from nightmares. The tension between the sisters and ?nju becomes deeper and deeper. Strange things begin to occur in the house. The relationship between Sumi and her father is shown to be a thorny one. One day, ?nju’s beloved birds are found dead, with one of them discovered on Suy?n’s bed. The antagonism between the two sisters and stepmother reaches its peak. Becoming increasingly convinced that the strange occurrences that are taking place within the house are the work of Sumi and Suy?n, ?nju bursts out into uncontrollable anger toward the two sisters and begins to suffer from neurosis. Sumi gets angry at Muhy?n for allowing ?nju to persistently torture Suy?n. Muhy?n responds by stating that Suy?n is already dead. A confused look comes across Suy?n’s face as Sumi yells and screams to an extent that we are left to think that she suffers from an anxiety disorder. Convinced that Suy?n has been with her all along, Sumi begins to show signs of mental confusion and schizophrenia.

The insert scene which shows a panoramic view of the house (night time) in Scene 78 is used to signal the end of the middle part of the film, and also to indicate the advent of a new stage in terms of the development of the story. In Scene 79, Muhyŏn can be seen talking to someone on the phone and saying that Sumi’s symptoms have worsened. Scenes 80–102 constitute the conclusion of the illusions (schizophrenia) created by Sumi’s multiple personalities. Ŭnju ruthlessly torments Suyŏn. Having discovered a big sack from which blood oozes out as well as bloodstains on the floor in the hallway, Sumi automatically assumes that Ŭnju has killed Suyŏn. This leads to a fierce fight between Sumi and Ŭnju. When Muhyŏn returns to the house, Sumi suddenly awakes from her illusion.

The emergence of the first dramatic reversal in the form of the revelation of Suy?n’s death, and of the second dramatic reversal, the disclosure that ?nju is in fact Sumi’s alter-ego, has the effect of moving the audience’s attention away from the horror itself, and towards the origins of Sumi’s multiple personality disorder. In other words, the audience begins to focus on the original accident that caused Sumi’s trauma. However, the film’s plot encounters difficulties as far as the establishment of such narratives is concerned. As such, the heretofore linear plot becomes disjointed at this juncture, leaving the audience confused.

Scenes 103–113 are used to inform the audience of the truth, namely that the previous situations were the result of Sumi’s mental illness and split personalities. We are made to understand that it is impossible for Sumi, who suffers from multiple personalities and has a schizophrenic outlook, to gain a grasp on reality. The confusion surrounding this film is depicted as the result of a segmented reality that is created by memories which are arbitrary, distractible, and capricious. In actuality, the memories of this extremely subjectified existence which destroys the organic relationship between the past and present, stands as proof positive of an internal pain that is motivated at once by a sense of guilt and defense mechanisms, desire and anger, and hatred and envy.18 These scenes make it possible for the audience to understand why Sumi is sent back to the mental facility (Scene 114–117). These hospital scenes can be regarded as a frame which is connected to Scene 1. In any case, we are made to understand that Sumi’s dissociative multiple personality disorder has not gotten any better. The previous situations imply that continuous rehashing of events is taking place in Sumi’s head. Weighed down by an immense sense of guilty, Sumi endlessly repeats these painful events within the space from which she cannot escape (her mind). In conclusion, all the events that unfold in the film are the result of the efforts made by Sumi, who has lost her mother and sister, to negotiate, fight, and ignore her sense of guilt occasioned by her hatred and envy of Ŭnju. As such, the film

As mentioned above, the narrative structure of

18To us humans, memories can be regarded as the basis which allows us to maintain and develop our identity as individuals. “Memories are the mental activity and process through which a person relates his past to the present. Memories define the already unfolded past on the one hand, and also change the temporal status of the past by bringing it to life in the present. While attached to each other like the two sides of a coin, memories and memory lapses can be regarded as mutually exclusive processes within man’s psyche. (Ch?n Chins?ng, History Tells Memories (Y?ksa ka ki?k ?l malhada), Humanist Publishing, 2005, p. 44) 19DJUNA, ibid. (Cine 21, Issue No. 408)

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE MAIN CHARACTERS AND ANALYSIS OF THE CHARACTERS

4-1) Relationship chart of the characters

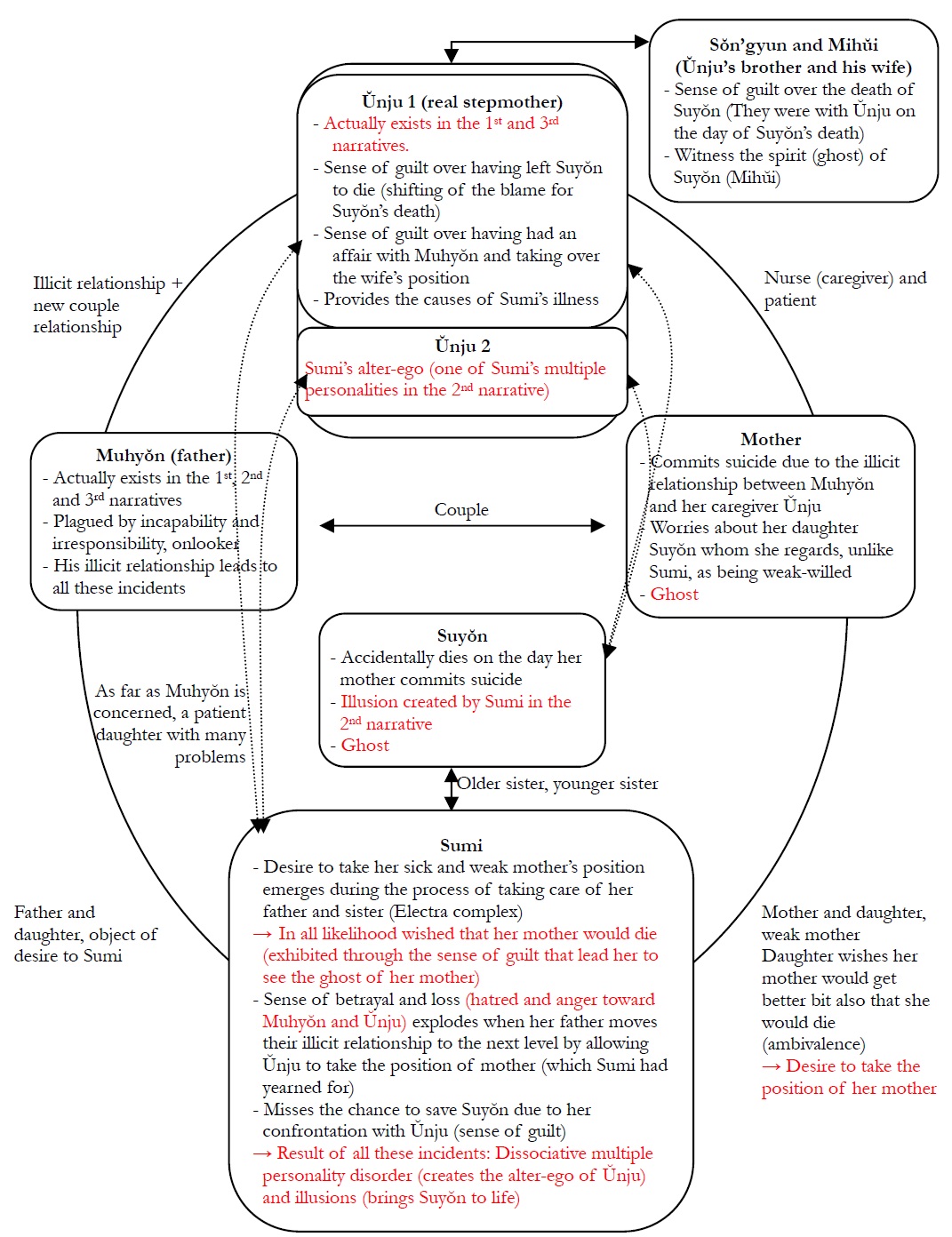

The following can be regarded as an analysis of the relationship between the film’s characters that is based on the breakdown of the text and analysis of the narrative carried out above. Let us first take a look at things from Sumi’s point of view. The mother’s prolonged period of medical treatment provides clues as to the causal relationship that exists between all the events and characters. Muhy?n (father) brings ?nju to the house as a caregiver for the mother, a move that is rooted in the illicit relationship that exists between them before and after this event. Their open relationship causes the mother’s tragic suicide. In a state of shock, Suy?n, who was the first to become aware of the death of her mother, begins to wail and convulse to the point where she finds herself crushed to death by the wardrobe in which her mother hung herself. ?nju 1 (real stepmother) is the first to come upstairs after hearing the sound of something falling. She sees Suy?n being crushed by the wardrobe but makes no attempt to save her. ?nju then comes face to face with Sumi in the hallway after having exited the bedroom. Sumi runs outside after having quarreled with ?nju, thereby missing the chance to save Suy?n. ?nju’s brother, S?n’gyun and his wife Mih?i, who were in the house when this incident occurred, also experience a tinge of guilt over the death of Suy?n. While seemingly cognizant of what is happening on the second floor (mother’s death), Muhy?n does not display any immediate reaction.

Meanwhile, the mother’s prolonged period of medical treatment produces the unwanted side effect that Sumi is unable to smoothly navigate through the Oedipus complex that inevitably appears during puberty. Having taken care of her father (ex. preparing her father’s underwear) and sister for her mother since her childhood, Sumi is automatically believed to suffer from an acute Electra complex. In this regard, young Sumi is continuously plagued by an internal struggle that sees her hopes for her mother’s recovery intersect with her desire for her mother to die. This is why her mother appears as a ghost to Sumi. It is Sumi’s sense of guilt that constantly evokes the ghost of her mother to appear before her.20 Then one day, the father brings ?nju home. ?nju pushes out their mother as she draws closer to the father, in the process breaking the heart of Sumi, who yearns for her father, to pieces. Then at the moment where the very existence of the mother has all but faded from the scene, ?nju comes to make her position next to the father official. Whereupon, the mother ended her life by committing suicide (thus creating an ending contrary to the one Sumi had envisioned in her head).

On the other hand, Suy?n is Sumi’s beloved sister. However, one day Suy?n begins having her first menstrual cycle. Suddenly, this sister who she had regarded as a young child (sexually immature) emerges as a potential competitor. The matching of Suy?n (and Sumi)’s menstrual cycle with that of ?nju is meant to denote that the number of fertile females (who can engage in sexual intercourse with Muhy?n) has increased to three. Sumi kills ?nju’s pet birds and hides one of them in Suy?n’s bed. The scene in which ?nju discovers the dead bird on Suy?n’s bed (Sumi’s illusion) clearly exhibits how Sumi starts to regard Suy?n. Therefore, the externalized version of Sumi’s illusions regarding the accidentally deceased Suy?n (characterized by her desire to protect Suy?n from ?nju), do not reflect the full gamut of emotions which she feels towards her sister. This highlights the fact that Sumi is internally plagued by a strong sense of ambivalence.

Lastly, Muhyŏn’s links to Ŭnju, a nurse at the hospital where he works as a pharmacist, are forged at a point in time where he has begun to grow weary of the prolonged medical treatment which his wife has been under. Muhyŏn draws close to Ŭnju who has been assigned as his wife’s care giver and eventually brings her into the house and family. Sumi immediately exhibits hostility toward the sudden appearance of Ŭnju alongside her father. She also exposes a strong sense of hostility and resentment toward her father for his actions. However, as Sumi’s actions are superficial expressions of her desire for her father’s love, she soon develops an extreme case of ambivalence toward Ŭnju that is characterized by the notions of hatred and envy.

The fact that Sumi’s head is constantly filled with a sense of guilt and desire causes here to repeatedly relive hellish experiences. As such, the driving force which defines the relationships between the characters and creates the causal relationship mechanism between them is Sumi’s trauma and her post-traumatic stress disorder, or schizophrenia, which leads to Sumi’s multiple personalities. Therefore, the showcasing of some aspects of Sumi’s schizophrenic cycle in a detailed manner and of the remainder in a manner that is sometimes segmented and sometimes not connected to the other elements of the story can be regarded as a justifiable approach.

4-2-1) The character of Sumi

Sumi has a very instable ego. She takes on the role of imaginary characters whose reality cannot be determined based on rationality, but at the same time possesses a very strong sense of self (Id). Her character is not ruled by any rationality or logic and appears to be devoid of any morality. Therefore, Sumi’s character is very complex. While the series of speeches and actions which she takes towards her sister Suy?n are meant to display Sumi’s image as a ‘mother’, her struggles with ?nju are meant to denote her image as a ‘teenage girl.’ Meanwhile, the anger and affection she displays towards her father are meant to signify her image as ‘a wife.’ Sumi’s ambivalence reflects on all of her family. In other words, she is overcome by extremely complex emotions, such as the sense of guilt and defense mechanism she feels towards her mother and Suy?n, desire and anger towards her father, and the hatred, revenge and envy which she feels towards ?nju. These are the core elements with which any reading of the character of Sumi found in the text should be based.

First, let us analyze Sumi’s ambivalence toward her mother. Sumi’s sense of guilt toward her mother is motivated by her inherent perception of her mother as a competitor. As a result, Sumi is tormented by two different thoughts, namely that while she wishes her mother could recover, she also yearns to take her mother’s place when the latter dies.

Second, let us look at Sumi’s relationship with Suy?n. Although Sumi loved Suy?n very much, the situation developed in a different direction after her secondary sexual characteristics appeared. As a result of this event, Sumi must now perceive Suy?n as a rival. For Sumi, Suy?n is both akin to a daughter whom she should love and protect, but on the other hand she has also become a competitor (Sumi’s ambivalence emerges). Sumi kills ?nju’s beloved birds and puts one on Suy?n’s bed. Such a move is designed to focus ?nju’s anger on her sister, and to make these two rivals fight one another. To this end, the following interpretation offered by Ch?ng S?nghun can be regarded as being on the mark, “in the Korean classic novel

However, Sumi cannot accept nor internally digest (mourn) the trauma occasioned by her mother’s tragic suicide and her sister Suy?n’s accidental death. Sumi’s reaction to the sound of the wardrobe falling that emanates from the second floor leaves open the possibility that she to some extent anticipated her mother’s suicide. In other words, for Sumi, who desired to sexually possess her father, her mother is an entity that she wishes would disappear. She has prepared herself to ignore the sound emanating from upstairs that she knows will signal her mother’s death. This sound in some ways marks the completion of her long-held dream fueled by her Electra complex of making her father her own. On the other hand, Sumi exhibits an extremely guarded attitude toward ?nju, an attitude that is motivated by the possibility that ?nju may take the spot vacated by her mother, that is that of the mother. However, it is another event that serves as the catalyst for her problems. While Sumi turns a blind eye to her mother’s death, she never thought that this event would also lead to her sister Suy?n’s accidental death. This can be perceived as the fundamental cause of Sumi’s post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and subsequent multiple personality disorder. In this regard, Sumi creates an ambivalent structure that encompasses both the sense of guilt she feels toward her mother and Suy?n and the defense mechanism she has developed to overcome such feelings of guilt. Sumi’s defense mechanism is a two-pronged one. More to the point, while she completely erases (excludes) Suy?n’s death from her memory, she also finds someone to blame for Suy?n’s death in order to lessen her own guilty consciousness for not having saved her sister. The object of her for wrath is ?nju, and before long Sumi creates a new alter-ego as a vicious stepmother who torments Suy?n. Having subconsciously equated herself with ?nju, Sumi also creates a new alter-ego of herself as a heroine who protects and shields her younger sister from harm. This is designed to absolve herself of the guilt she feels at having failed to save her sister.

Third, let us take a look at Sumi’s ambivalence toward her father Muhyŏn. For Sumi, who desired to take her mother’s place, her father is guilty of having had an illicit relationship with Ŭnju and of having brought her into the house while her mother was still alive. These actions on the part of her father have the effect of breaking Sumi’s excessively pure (naive) heart. Unable to accept this situation, Sumi begins to be filled with a sense of hatred. Unable to stand the sight of Ŭnju in the kitchen acting like she was the new lady of the household and assuming the position of wife to her father, Sumi becomes strongly antagonistic. She even refers to her father as ‘dirty’ at some point.

Lastly, let us take a look at Sumi’s ambivalence and identification with ?nju. Unaware or ambiguous towards the sexual role created by his daughter Sumi vis-avis her father (Muhy?n), the latter proceeds to disregard Sumi’s desires and bring ?nju into their household. For Sumi, this marks the emergence of a new and strong competitor and of an unacceptable challenge. While Sumi was in the past able to play the role of wife, the arrival of a young and pretty stepmother serves to highlight her inherent limitations in such a role, which in turn causes her to become even more confused in her identity as wife and daughter. This leads Sumi to cause a scene at the dinner table by throwing her spoon down as everyone else watches on. By this point, the ambivalence characterized by her spirit of competition (hatred) and envy (admiration) toward ?nju, who came in the house as a stepmother and took away her father, has thus been created.

This ambivalence toward ?nju is greatly impacted by a sudden accident that leads to a new phase. As previously mentioned, Sumi suffers the traumatic experience of losing her mother to suicide and her sister Suy?n to an accidental death. Sumi immediately begins to activate her defense mechanism. As part of this self-defense mechanism designed to remove the sense of guilt she feels at having failed to save her sister, Sumi erases (deletes) Suy?n’s death from her memories and even creates an entity who she can blame for Suy?n’s death. To this end, ?nju proves to be a perfect foil. By not only blaming ?nju for her sister’s death, but also developing a cruel image of the stepmother who continuously mistreats her sister that effectively allows her to create a new alter-ego (identification) of herself as ?nju, Sumi is able to erect a multi-layered defense shield. Thus, we have moved beyond the simple competition (hatred) with ?nju that exists at the beginning and into a new stage marked by the desire for revenge (punishment). While the alter-ego of ?nju which Sumi has created in her head personifies the image of the cruel stepmother who continuously mistreats Sumi and Suy?n, Sumi’s true ego plays the role of protecting and shielding her sister, an exercise that is carried out in order to be forgiven and escape from the sense of guilt which she feels for having failed to save her sister. Therefore, ?nju superficially becomes the direct cause of her mother and Suy?n’s deaths, and an object of rancor and of evil which mistreats Suy?n (in Sumi’s illusions). This stems from Sumi’s illusions in which she imposes the role of classic villain on ?nju as a means of justifying her attempts to protect her sister like a mother would. In other words, ?nju (Sumi) becomes a hostile assistant which lessens the real Sumi’s sense of guilt.

On the other hand, there is also a different point in time in the story where Sumi evokes ?nju, whom she has already pulled into her ego, only this time for different reasons. It is the point in time where her other rivals, namely her mother and Suy?n, have suddenly disappeared. At this point, Sumi seeks to evoke ?nju, who has engrossed Muhy?n’s love, as an ‘agent (of desire)’ capable of satisfying her own desires. The obscure envy which Sumi showcased at the beginning suddenly becomes much clearer. Another image that we are shown of ?nju is that of the temptress who seeks to seduce Muhy?n with her coquettish behavior. At this moment, while the agent ?nju becomes the ideal ego which the real Sumi yearns to be, the rival ?nju (the subject of hatred) takes on the image of the superego that seeks to control such desires. However, the multiple memories which Sumi carries with her because of her triple personality disorder, in that she has incorporated not only ?nju as an alter-ego but also Suy?n, becomes the impetus that propels Sumi into seemingly boundless instability and fear. To this end, Sumi’s desires, which are reflected through the ?nju alter-ego, are laden with an emptiness that cannot be satisfied and does not allow her to experience any pleasure.

The reason why the film

4-2-2) Muhy?n

Muhy?n is the cause of all the events that unfold in this film. While he is of course not responsible for his wife’s serious illness and her long?term medical care, he eventually abandons all hope for his wife who has become bed-ridden because her disease has taken a turn for the worse. From that point onwards, it is as if the burden of reality has been lifted from his shoulders, and he appears to be imbibed by a new found sense of freedom. The director Kim Chiun revealed the following in a dialogue which he had with his counterpart Yun Chongch’an.

He brings ?nju into the house as a caregiver for the mother. While it is unknown whether they have simply drawn rapidly closer to each other because of this time together or whether they have already been engaged in an illicit relationship, the latter seems like a more probable scenario. In a mere matter of seconds Muhy?n has lost his authority and prestige as the head of the family in the eyes of his wife and two daughters. The wife’s tragic suicide and Suy?n’s accidental death are the results of Muhy?n’s actions. Although Sumi’s illness is a complex matter, Muhy?n must inevitably be perceived as the one who represents the cause of Sumi’s illness. More to the point, the fissures that eventually break this family apart do not begin with the appearance of the young stepmother ?nju, but rather stem from Muhy?n’s helplessness, insensitivity, and irresponsibility vis-a-vis his family.

Muhy?n simply stands by as a helpless onlooker and watches Sumi’s illness worsen and her schizophrenic behavior unfold. The only thing that he can do is to make Sumi take two pills every day. Muhy?n already knows that Sumi has created new alter-egos called ?nju and Suy?n and that she identifies herself with these characters, even going as far as to talk and behave like them. As such, while he continues to generally ignore Sumi’s behavior, he to some extent accepts it. A perfect example of this occurs when Sumi, as her alter-ego ?nju, lies down on Muhy?n’s bed as if they were a couple. Muhy?n simply gets up and goes to the sofa in the living room. He does not clearly expose any morally conscious behavior regarding his obscure relationship with Sumi or make any special attempt to help Sumi become healthy once again. Furthermore, at the time of Suy?n’s accident (when the wardrobe falls down) following the mother’s death, he does not take any action other than stand in the yard and look toward the second floor of the house in a manner than conveys his belief that something strange (a serious accident) has happened. This event stands out as proof positive of the extent of Muhy?n’s insensitive and irresponsible response to the events that unfold in the house. Put differently, Muhy?n is depicted in a manner that denotes the fact that he does not have any direct responsibility for his wife’s suicide, his daughter Suy?n’s death, Sumi’s mental illness or his new wife ?nju’s pain. As a result, he is not consumed by fear occasioned by a sense of guilt and ghosts do not directly appear before him. He does not show any sign or engage in any behavior that might indicate that he is devoted to his family on any emotional level, and does not address any emotional problems which emerge within the family. Through his shortcomings and indifference toward everything that occurs within the family, Muhy?n is ironically located at the center of patriarchal authority. It is the image of Muhy?n (father and patriarch) ‘as someone who has been granted exceptional indulgence,’ that has caused previous studies to relate the film to the classic novel,

In fact, depending on what prism the audience views the film from,

20The nature of the ghosts that appear in this film is completely different from that of the ghosts in the original classic novel. The ghosts in the original novel are motivated by a profound grudge. However, the ghosts in the film do not represent that kind of existence. The people who are afraid of the ghosts in the film, namely ?nju (stepmother), Sumi, and S?n’gyu’s wife are all women, women who are consumed by their own sense of guilt. ?nju’s sense of guilt stems from the fact that she was somehow related to the death of Suy?n as well as the mother’s suicide. S?n’gyu’s wife was also with ?nju when the incident occurred. Sumi’s mental state is much more complicated. To this end, all of these women are consumed by a sense of guilt that renders their viewing of specters an almost natural occurrence. (The ghosts do not appear to men and the men do not see any ghosts). The ghosts in this film do not emerge because of a thirst for revenge, but rather are evoked by the women’s inherent sense of guilt. 21Ch?ng S?nghun, “Although it fails to overcome the physical science aspect of horror, Changhwa Hongny?n is a work one cannot avert one’s eyes from” (Kongp’o ?i hy?ngyihahak ?l n?mji mothaetchiman nun?l ttelsu ?mn?n y?nghwa, Changhwa Hongny?n)”, Cine 21, Issue No. 408, July 1, 2003. 22Kim Hyeri, ibid. 23Sim Y?ngs?p’s interpretation should be seen as an extension of Ch?n’s criticism. This is because Sim reads Kim Chiun’s desires based on imaging modalities rather than at the narrative level.

Based on an analytical approach, this study has made it clear that the film

There are many elements of this film which were not analyzed nor discussed herein. Many of these elements await new viewpoints and interpretations. These include an examination of the background of the film and the use of an analytical approach to the spatial arrangements found therein. In cases where stories deal with events that transpire in limited spaces, detailed descriptions of characters, as well as the meaning of the metonymic relationship between the characters and background (place, space), often become the key points through which to understand the text. While the characters bestow meaning upon the spaces, the latter play the role of helping to define the dramatic personality of the characters.25

In this sense, the house as the background in which

The inside and outside of the house represent the most important symbols in this film. The external appearance of the house (male = Japanese wooden house) represents the essence of patriarchy, while the internal decorations and furniture (female) represent the essence of the wife. Director Kim Chiun’s intention is to tell the story of vestiges of something that ‘have not yet been cleared up.’ Director Kim purposefully decorated the interior of the Japanese-style wooden house with Western-style furniture. In an interview, he likened this to the spiritual state of modern and contemporary Korean history in which the vestiges of the Japanese colonial era and the transplanted culture that developed during the USAMGIK (United States Army Military Government in Korea) period have become intertwined disorder.26 However, these remarks can be perceived as the most foolish comments which Kim has made during the interviews he has given for

Based on the connectivity with the film’s narrative, this house, which becomes the dramatic background in which the story unfolds, represents the relationship between Muhy?n and his wife. Simply put, Muhy?n and his wife do not appear to have been a well-matched couple. The current state of the house in which the story unfolds serves as a hint of this couple’s life together. Their different tastes and methods led them to take care of their house in an inharmonic manner. Perhaps, the disharmony that exists between the couple is in fact the root cause of the wife’s illness. Conversely, the wife’s prolonged disease can be seen as the reason why she decorated the inside of the house in such an unstable manner. Here again, Kim Chiun made a misguided comment. He stated, “I also tried to keep the eerie effects occasioned by this conflict in mind when mixing the heterogeneous elements. Whenever a piece of furniture was introduced, I thoroughly sought to incorporate such elements as the texture of the table and the curves on the chair when the camera panned around behind the table. This was done with the expectation that even though this was not overtly exposed in the film, the furniture could be used to convey the overall aura.”27

Despite the sincere decorations used to convey the background which helps to create the dramatic details of the film, the director inexplicably never requires the audience to relate this background to the context of the film in terms of the extension of the narrative. The inside and outside of this house, which are very heterogeneous, eerily beautiful, and yet not harmonious, and the elements inside the house clearly expose the lack of organicity that exists between the family members, and this despite the fact that they have lived together in these common spaces as a family. This is where this film’s story actually begins. This is the origin of all the events that unfold in the house, including the opportunity for Sumi to take the place of her mother, whom she regards as a rival, as the latter lies on her sickbed; opportunity for Sumi to further strengthen her desires vis-a-vis her father; and the opportunity for Muhy?n to engage in an illicit relationship with ?nju and eventually bring her into this house.28

In conclusion, Sumi has no choice but to escape these spaces that exist within the house, both in a physical and mental manner. This action marks the first step towards her being cured of her illness. It is this house that repetitively disrupts Sumi’s ego and leads to the emergence of her multiple personalities. Sumi’s act of leaving the house can in many ways be equated with her escape from these oppressive spaces that have marked her past. It is then and only then that she can possibly develop a new acceptance of reality. The external world leaves Sumi feeling like she is an instable being which has just been removed from the mirror stage. But at the same time, it is also a space that leaves her feeling like she truly exists. The external world can be seen as both the transitional space advanced by Jacques Lacan and the flexible cognitive space. The transition is designed to show us how the truth of life is based on illusions and to reveal the manner in which life can be lived.

While interesting debates can also be had in conjunction with many other aspects of this film, such as the sound and music, use of colors, and image expression methods, the lack of space herein makes it necessary to address these issues at a later date.

24DJUNA, ibid., Cine 21, Issue No. 417, August 29, 2003. 25S? Ch?ngnam, Study of Film Narratives (Y?nghwa s?sahak), Saenggak ?i namu Publishing, 2004, p. 246. 26Kim Hyeri (summary), ibid. 27Kim Hyeri (summary), ibid. 28As long as this is not another trick designed to delay the interpretation of the text, such attempts to tell a different story after having created an atmosphere in which the audience is expected to guess that the cause and effect of all the problems were originated from the house can only be regarded as foolish.