Ⅰ. English and American Linguistic Hegemony

Linguistic hegemony is a form of power that empowers some while disempowering others.1) The power dynamics of American English affect other countries through political, socioeconomic, and cultural dynamics. There is a growing consensus that the world is becoming culturally globalized by the exchange of goods, information, technology, and capital. More recently, the emergence of international organizations and economic and political competition have accelerated these power dynamic flows.

Under globalization, the English language functions very effectively as a common linguistic medium. English as an international language provides many advantages, i.e., educational and employment opportunities. Scholars and scientists especially benefit from the volume of academic information available in English and have more chances to disseminate their academic achievement to other scholars worldwide. Learning English as an international language provides an access to popular American culture (e.g., Hollywood films, television soap operas, music, international news and other forms of mass media). As there is a great deal of convenience in common communication, international and intercultural exchanges of products, as well as the ideas and values, have been welcomed by most people of the world. Most significantly, the main communication tool in exchange of intercultural products is ‘English’, and learning English is a mechanism for participating in mass consumer culture.

How does a language become an international language? According to David Crystal, language becomes a global language for one chief reason: the political power of its people, especially their military power.2) However, military dominance is not the only determinant of international language dominance. The influence of economic power is equally important to maintain and expand global power. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, Britain became the world’s leading industrial and trading country; but by the end of the century, the United States took the lead and became the largest economy in the world. Rather than military and economic factors, soft power (e.g., culture and cultural products) became more effective in exercising US dominance with language as an important part of cultural and a powerful influence.

Language testing is another form of power since the results obtained from tests have serious consequences for individuals as well as societies. Michel Foucault describes tests as the most powerful and efficient tool through which society imposes discipline.3) In

This article empirically analyzes how American linguistic hegemony is consolidated through the ETS case. Specifically, this study examines how American linguistic hegemony maintains and delivers US norms and values via the medium of American standard English proficiency tests. The American linguistic power is structured for the US foundations, ETS, and universities to be related to the US government. Power coalitions among the US foundations, ETS, and universities have become a driving force for the ETS to spread throughout the overseas market, which would have been impossible without US government support. Moreover, this study examines how American linguistic hegemony is consolidated in South Korea through the ETS. Specifically, as a powerful EFL testing corporation, the ETS has an enormous socioeconomic impact, especially on national spending. Along with the empirical evidence of the socioeconomic impact of EFL tests, the washback effect of American EFL tests is examined to better understand its power to inclusively lead Korean education to be Americanized as a result of content, pronunciation, and learning materials.

1)John Rennie Short, et al., “Cultural Globalization, Global English, and Geography Journals,” Association of American Geographers 53-1 (2001), pp. 1-11. 2)David Crystal, English as a Global Language (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), p. 7. 3)Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish (New York: Vintage Books, 1979), cited from Elana Shohamy, “The Power of Tests: The Impact of Language Tests on Teaching and Learning,” National Foreign Language Center Occasional Papers (1993), pp. 1-23.

Ⅱ. The English Language and Linguistic Hegemony

Linguistic hegemony, which is the main theme of this study, is based on cultural hegemony. Culture is a difficult concept. Allastair Pennycook identifies a number of different meanings of culture. First, culture is set of superior values, especially embodied in works of art and limited to a small elite. Second, culture is a whole way of life, the informing spirit of a people. Third, culture is the way in which different people make sense of their lives.4) Traditional realists often do not consider the relevance of culture in international relations. For instance, Hans Morgenthau argues that “the problem of world community is a moral and political and not an intellectual and aesthetic one.” In his perspective, the real issues are constituted by power politics, therefore institutions like UNESCO have little relevance to traditional realists.5)

Since the end of the Cold War, the debate on US soft power has flourished. American culture is highly evident in the various products, technology, and communication it produces. It satisfies universal preferences, which eventually lead to a universal legitimacy of American influence, not withstanding its political and economic intentions underlying it. For example, the US dominates mass media, such as newspapers, magazines, and books. Moreover, the feature film, star system, the movie mogul, and the grand studio are all based in Hollywood, California. The commonality of this phenomenon is that American cultural hegemony is based on a single language, ‘English’.

There is a growing consensus that American hegemony has declined since the 1970s. However, some scholars insist that the United States still maintains hegemony. Joseph Nye accepts the fact that the economic power of the United States has weakened compared to earlier times; however, the United States still remains a leading power in different dimensions. He claims that as the international environment changes, diverse resources which form hegemony have to be considered with relative importance.6) In other words, American soft power (e.g., culture, values, and ideology) are more important dimensions of power which can maintain American hegemony.

American cultural hegemony is closely related to American linguistic hegemony. Gramsci’s cultural hegemony refers to the “spontaneous consent given by the great masses of the population to the general direction imposed on social life by the dominant fundamental group; this consent is historically caused by the prestige which the dominant group enjoys because of its position and function in the world of production.”7) According to Nye, soft power is a more attractive and indirect way of exercising power that “one country gets other countries to want what it wants.”8) Therefore, the United States is able to exercise its power through the global spread of American culture in the medium of American English, which is more pervasive in terms of its indirect effect. Some people may argue that Americanization of culture is changing only the surface of local culture across the world and it is beneficial for the people of non-native speaking nations. However the impact of Americanization of culture penetrates the norms and values in the medium of English. As Tsuda argues, “the invasion of English and American culture is causing not only the replacement of language, but also the replacement of mental structure.”9)

The theoretical framework of linguistic hegemony is closely related to linguistic imperialism. Robert Phillipson argues that English achieved its dominant position as the principal world language because it has been actively promoted as an instrument of foreign policy of the major Englishspeaking states.10) The language policies that third world countries reproduce as a result of colonization serve the first and the foremost interests of Western powers and contribute to preserve existing inequalities between countries and what Phillipson calls English linguistic imperialism.11)

Phillipson’s studies clearly demonstrate the current position of English as a global language. He argues that the current position of English is not an accidental or natural result of forces. Rather, English-speaking countries, including the United States and the United Kingdom, deliberately use government policies to promote the worldwide use of English for economic and political purposes.12)

Hence, the English language is so widely used today that teaching and learning English has become a major business of high commercial value. The spread of the English language education is not only good for business, but it is “

Although this is the British business case for English language teaching, it is also applicable to the United States. According to the above empirical statement, there is apparent commercial value in teaching the English language. In this regard, to learn English as an international language, customers not only spend their financial resources, but also receive a better understanding of its history and culture regardless of their purposes for learning English.

Phillipson distinguished between “core” and “periphery” English-speaking countries. In his framework, the core English-speaking countries are the United States, Britain, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. The periphery English-speaking countries are of the following two types: 1) English serves as an important but limited communicative function as an “international link language” in Japan, Scandinavia and elsewhere; and 2) in countries such as India, Nigeria, Ghana, and elsewhere, English was imposed in colonial times and was “

Though it seems similar to that of Kachru’s inner, outer, and expanding circles, Phillipson’s framework differs markably from that of Kachru’s in a key way. Phillipson focuses on the unequal distribution of benefits from the spread of English. His concept of “core” and “periphery” are adopted from the development studies, in which dominant core countries exercise major control over the economic and political fate of periphery countries. Phillipson’s analysis states that English plays a fundamental role in sociopolitical processes of imperialism and neocolonialism.15) In this context, the spread of English can never be neutral but is always drawn to global inequality. So while Kachru insists that the spread of English demonstrates positive effects on socioeconomic development, Phillipson argues that the spread of English is positive primarily in core countries, and harmful to those people living in the periphery. Therefore, the spread of English is a “

The scholars who agree upon the idea of English imperialism criticize David Crystal’s assumption that English is exclusively good for the North – South relations. According to Crystal, the world presence of English “was maintained and promoted, almost single-handedly during the twentieth century, through the economic supremacy of the new American superpower.”17) From the English imperialist point of view, the United States as a single superpower would have never achieved its goal without the help of international organizations such as the World Bank, the development aid, and colonial education.

4)Allastair Pennycook, The Cultural Politics of English as an International Language (London: Longman Group Ltd., 1994). 5)Ibid., p. 62. 6)Joseph S. Nye, Bound to Lead: The Changing Nature of American Power (New York: Basic Books, 1990). 7)Jackson Lears, “The Concept of Cultural Hegemony: Problems and Possibilities,” American Historical Review 9-3 (1985), p. 568. 8)Joseph S. Nye, Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics (New York: Public Affairs, 2004). 9)Yukio Tsuda, “English Hegemony and English Divide,” China Media Research 4-1 (2008), pp. 47-55. 10)Robert Phillison, Linguistic Imperialism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992). 11)Allastair Pennycook, op. cit. 12)Robert Phillipson, “Globalizing English: Are Linguistic Human Rights an Alternative to Linguistic Imperialism?” Language Sciences 20-1 (1998), pp. 101-112. 13)Allastair Pennycook, op. cit., recited in James Corcoran, “Linguistic Imperialism and the Political Economy of Global English Language Teaching,” paper prepared for the 2009 Meeting of the Latin American Studies Association, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 11-14 June 2009. 14)Robert Phillipson, op. cit. (1992) , cited from J. W. Tollefson, “Policy and Ideology in the Spread of English,” retrieved online at

Ⅲ. American Linguistic Hegemony and Educational Testing Service (ETS)

Considering the US domestic and international policy in spreading standard American English, it is clear that American English as an international language is not a natural or accidental process, but rather the result of a billion dollar effort by the US government and institutions worldwide. The mechanism of American linguistic hegemony was influenced by the ideology of philanthropy of the US foundations. The foundations’ role as silent partners in US foreign policy cannot be understood without analyzing their underlying assumptions.18)

On the basis of American philanthropy in education and foreign language teaching, it is closely connected to the creation of American EFL tests. In addition, the College Board and the universities played an important role in developing the American EFL tests. Most significantly, the ETS under the status of nonprofit organizations has been supported by the US government, such that the ETS is exempt from paying federal corporate income tax on many of its domestic operations when paying tax from overseas markets.

This section examines the mechanism of American hegemony and four actors constituting the power coalition of linguistic hegemony: the US foundations, ETS, universities, and the US government.

1. US Philanthropy: The Role of US Foundations

The US foundations, in cooperation with US foreign policy agencies, provide the financial resources to construct US linguistic power structure. They grant financial aid to educational institutions, not only internationally, but also domestically. According to Inderjeet Parmer, “the international efforts of the US foundations are widely acknowledged to have their origins in their prior domestic experience.”19)

This humanitarianism approach of the US institutions was shaped by their ethnocentrism, class interests, and their support of imperialist objectives of their own country. Though their humanitarianism was expressed in their programs, their underlying assumption was to deliver American norms and values through American education in the medium of American standardized English. Moreover, it was so intertwined with the interests of American capitalism as to be indistinguishable.

The Carnegie Corporation and the Rockefeller Foundation represented ‘scientific philanthropy’, which is a rational activity that sought to maximize its effects on social and other problems of order and stability.20) In order to justify their activities, these foundations advanced the theory of human capital development by funding higher education and research on education. In this approach, all people are considered educable so that education became a means of constructing human capital.21) The US foundations’ international behavior is called ‘philanthropy’ or ‘humanitarianism’ but its underlying intention is to foster and consolidate global hegemony.

The United States consolidated its power through a vast range of institutions—political, economic, academic, and cultural. Fulbright awards (administered by the Department of State) and awards from the Ford, Rockefeller, and Carnegie Foundations, among others, plus involvement by the Agency for International Development, the US Office of Education, the Department of Defense and the Peace Corps, have all contributed to the global spread of English, American ideology, capitalism, and US power.22) One of the most interesting involvements here has been the role of the great ‘philanthropic’ foundations.

2. Political Intention of the College Board and Universities

The US universities and their relationships with the College Board and the ETS set the standard for the admission of foreign students—another case of English competence tests used for political purposes.

In the United States, the use of English tests for foreign students began in the 1930s The College Entrance Examination Board (CEEB) tried to establish some degree of uniformity in admission standard for the elite Ivy League universities.23) According to Lyle Bachman, the motivation for the American English test for foreigners was more political and eugenic rather than educational.24) For instance, the US Immigrant Act of 1924 contained a significant loophole, allowing the granting of special visas to any foreign student whose sole purpose was to study in the United States.25) Since there was no restriction or standard entrance of allowing foreign students, the number of foreign applicants seeking admission to the US educational institutions rapidly increased. As a consequence, the US Commissioner General of Immigration wrote the following in a memorandum:

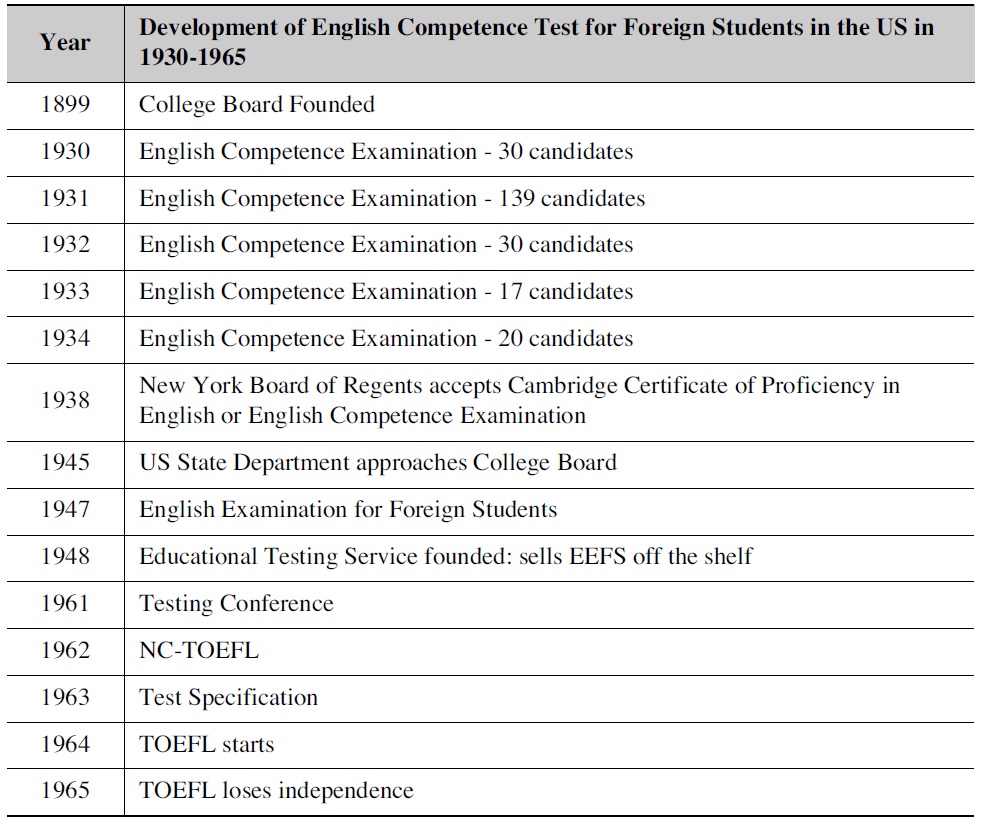

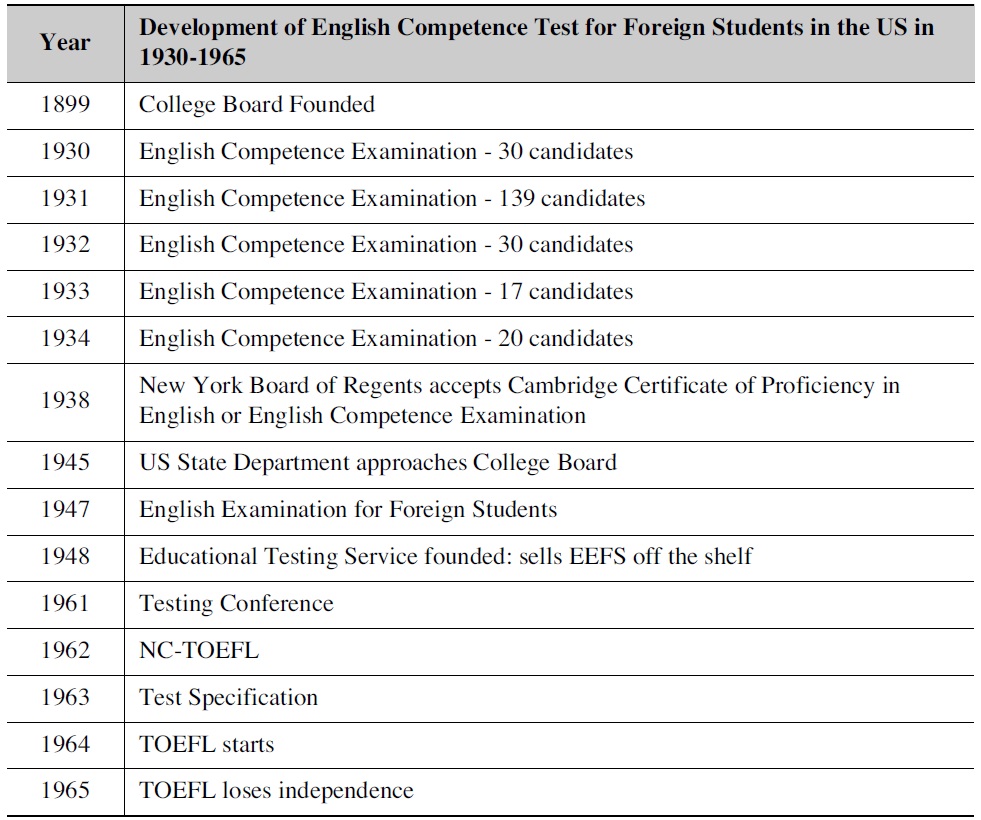

In conjunction with this official movement, the American Association of Collegiate Registrars adopted a resolution asking the CEEB to prepare an examination designed to test the English skills of foreign students to determine whether they should be admitted to study at American collegiate institutions or not. In April 1928, the CEEB set up a commission of English instructors and admission officers to develop an examination measuring foreign student applicants “ability to understand written English, to read English intelligibly, to understand spoken English, and to express his/her thoughts intelligibly in spoken English.” After six months, the CEEB accepted the report, and this plan of examination approved a grant of $5,000 from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace to cover its costs. The first English Competence Examination was taken by thirty candidates (Table 1). In the following year, 139 candidates from seventeen different countries took the test.27) In 1932, the test was offered in twenty-nine countries but there were steep declines in the number of candidates due to the worldwide impact of the Great Depression. Nevertheless, the numbers of test-takers decreased continuously even though sufficient funds were available from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace to finance examinations in 1933. However, by 1934 the funds were no longer available and therefore the CEEB was unable to offer the English competence test to foreign candidates wishing to attend American universities.

The Development of English Competence Test for Foreign Students in the United States, 1930-1965

After 1933, the English Competence Test, which was developed in 1930, was never reused. However, at the end of World War II in 1945, the US Department of State approached the CEEB and suggested that such a test would be helpful “in eliminating at the source, foreign students desirous of federal or other support for study in the country, whose command of English is inadequate.” Therefore, the experimental forms of the new examination, which included a number of paragraphs on historical and cultural topics recorded on gramophone records, were multiple choice questions in a booklet. However, the test had serious administrative problems and claims of poor cooperation of the Department of State, so it was transferred to the newly created ETS administrative body.

The third American effort to institute an English competence examination for foreign students was finally successful. In 1962, the National Council on the Testing of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) was established and the contract was given to the ETS to provide technical assistance in editing, printing, administering, and scoring the new test.28) After two years of operation, the council handed over the test to the joint control of the CEEB and the ETS, due to the funding uncertainties. The CEEB subsequently gave up its share in ownership so that the ETS became the sole owner of the test. Consequently, TOEFL proceeded to grow as the second largest program in the ETS.

Nevertheless, the TOEFL program was initially developed to measure the English proficiency of nonnative speakers who wanted to study at colleges and universities in the United States and Canada and to determine whether students had enough proficiency to successfully complete courses in local educational institutions. The TOEFL is also widely used as a means to measure English proficiency for employment and many other purposes. Today, TOEFL’s influence extends beyond academia, with many government agencies, school programs, and licensing/certification agencies using TOEFL scores to evaluate the applicants’ English proficiency.

The Test of English for International Communication (TOEIC) is also widely used as an international English proficiency test, particularly in East Asian countries (i.e., Japan, South Korea, and China). In its informational brochure, the TOEIC is described as “designed to test the English language as it is used internationally in business, commerce, and industry.” Close to two million people were administered the TOEIC worldwide in 2002 since the test was employed, primarily for assessing the English proficiency of applicants in the international corporate workplace, not only in East Asia, but also in the United States. For instance, the TOEIC is used as part of a battery of tests to license foreign-born professionals, as well as entrance examination for admission to some universities. Moreover, TOEIC scores are included in most job description requirements in Europe when applying to major firms (e.g., AirbusⓇ, Coca ColaⓇ, and UnileverⓇ). Even in Japan, multinational corporations like Honda, Toyota, and Nisan all require various levels of TOEIC scores as a requirement for employment. TOEIC is currently used by several thousand firms and other institutions worldwide, with specific score requirements established by each firm for different job categories. Also, there are marginalized scores that are mandatorily required for all applicants. Thus applicants are initially sorted out by the English proficiency scores before their applications are accepted. In this regard, each applicant taking the TOEIC test receives an ‘official diploma-quality’ TOEIC Score Certificate, which is considered as a credential in many business corporate fields.

3. Educational Testing Service: High-Stakes Testing Corporation under Nonprofit Status

According to Allan Nairn, the ETS comprises “an international network with more outposts than the US Department of Defense, and extends from Antarctica to Zaire.”29) Nairn illustrated how the ETS expands its influence throughout the world without resistance. Since the ETS owns, designs, administers, and evaluates the TOEFL, its subsidiaries have branches all over the world, and its influence continues to spread. TOEFL expands not only the influence of the ETS but also its revenues. Currently the minimum fee is $120. It is apparent that “testing is power” and “the teaching and testing of English are, in a large sense, political acts.”

The ETS represent itself as a nonprofit organization. In the United States the term nonprofit refers to how an organization is incorporated under state law. Some corporations, and any community chest, fund or foundations are exempt from federal income tax under code section 501 (c) (3). There are some important criteria in order to be federally tax exempt. First, an organization must set exclusively for one or more of the following purposes: charitable, religious, educational, scientific, literary, testing for public safety, fostering amateur national or international sports competition, or the prevention of cruelty to children or animals.30) Among these purposes, the ETS’s exempt purpose is “educational.” Second, an organization’s officers, directors, trustees should not benefit from the organization’s net earnings either directly or indirectly. Third, the organization may not engage in lobbying with legislation other than an incidental part of its activities. Fourth, the organization may not in any way participate in any campaign for public office. Fifth, the organization’s activities must principally benefit either the public in a sufficiently large part and for a distinct class of persons to be broadly characterized as charitable, and it may not benefit private persons not constituting a charitable class. Sixth, the organization may not engage in activities that violate law or fundamental public policy.31)

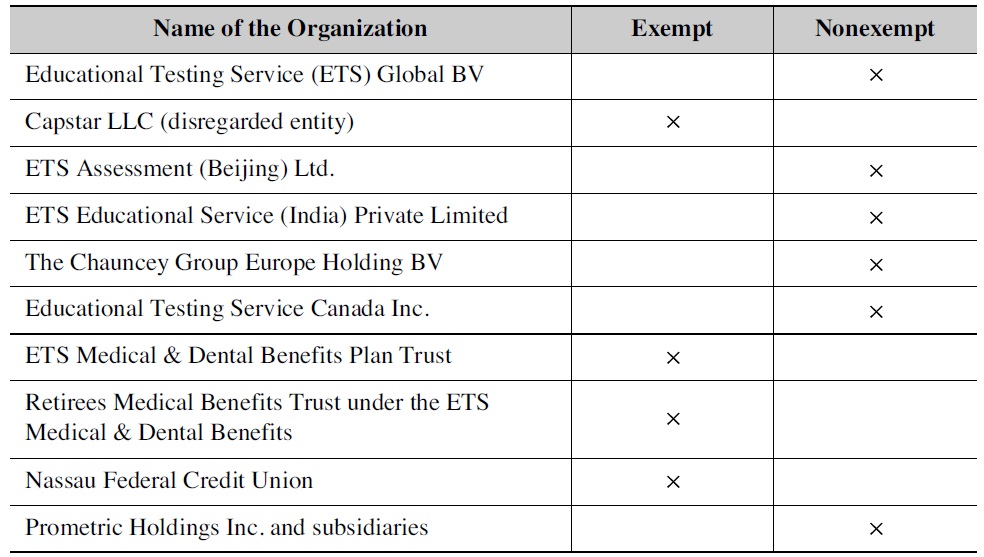

In this context, Section 501 (c) (3) does not allow organizations to engage in activities unrelated to their exempt purposes.32) However, those activities must not become “substantial” and tax must generally be paid on unrelated business income. Therefore, nonprofit organizations create for-profit subsidiaries for a variety of business reasons. For instance, the parent organization is operating too much income from businesses that are not related to its non-profit corporate purpose. In this case, the organization may set up a for-profit subsidiary to go after businesses unrelated to its central purpose.

Domestically, the ETS is supported mostly by the government in terms of its nonprofit educational mission. To help support its nonprofit status, the ETS conducts business activities outside of the United States. Under the US tax law, these activities can be conducted by the nonprofit organization itself or by for profit subsidiaries. One of the prominent business activities of ETS is the business of international testing. PrometicⓇ is a for-profit subsidiary of the ETS that provides tests to many third-party clients. Also ETS Global BVⓇ (e.g., ETS ChinaⓇ and ETS CanadaⓇ) contains much of the international company operations.

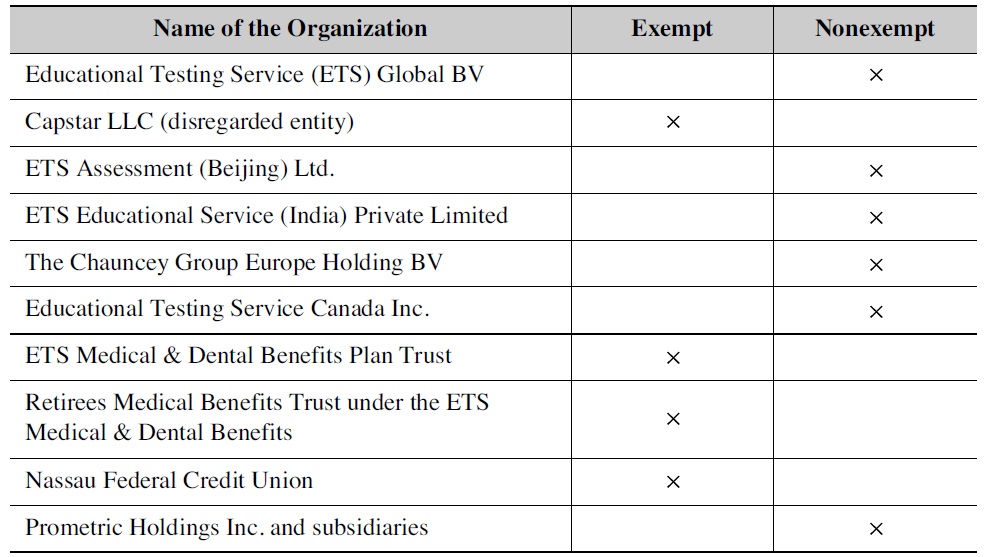

The ETS has several for-profit subsidiaries of the organization (Table 2). Importantly, the ETS Global BV and ETS Canada, which were formerly TOEIC Service Canada Inc., are not subject to tax-exemption. In other words, most of the international business activities of ETS are for-profit. The Chauncey Group InternationalⓇ is also subject to nonexemption. It was established as a for profit subsidiary of the ETS on January 1, 1996, to expand its parent’s market share in developing, and administering, licensing, and certification of tests, for professional organizations and exams for US government activities.33) Named after Henry Chauncey, the founder of the testing service, the organization started with approximately 100 employees and assets of nearly $20 million, most of them in the form of existing test accounts from its parent organization.

[Table 2.] Internal Revenue Service (IRS), Form 990, Part IV, Line 80b

Internal Revenue Service (IRS), Form 990, Part IV, Line 80b

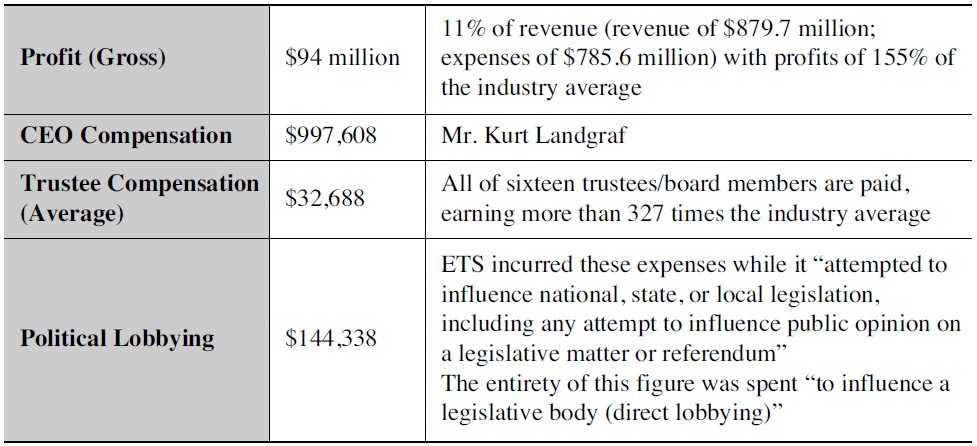

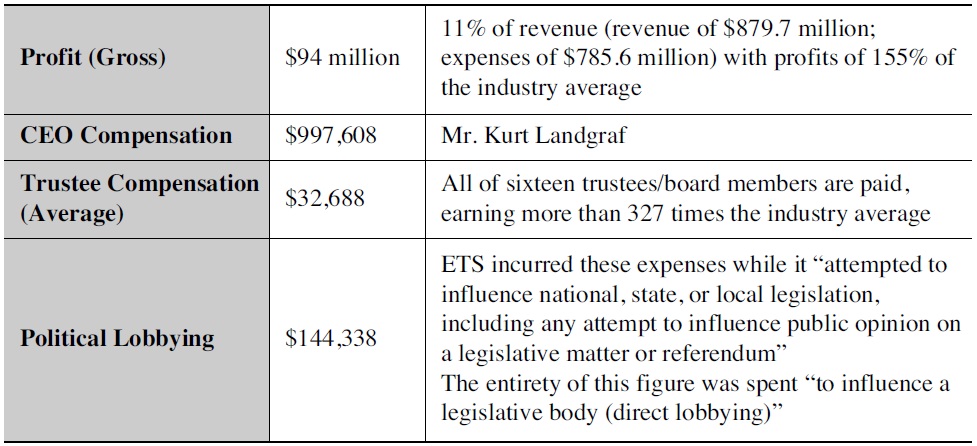

For large testing agencies, the financial stakes are very high. Spolsky reports that, in 1987-1988, the ETS received approximately US$15 million for operating costs of TOEFL, and that the ETS senior officials were paid more than twice the average salaries of comparable university officials.34) In 2002, the ETS administered more than 12 million tests worldwide, with estimated revenue of $700 million. Kurt Landgraf took over the ETS in 2000 and embarked as an aggressive expansion into overseas market.35) He has worked in Dupont Pharmaceuticals for twenty years, and as CEO he gained the reputation there for “maximizing income through global sales.”36) He has already announced to the press that his main agenda for ETS is to “increase the revenues.” ETS International BV headquartered in Utrecht, Netherlands, opened as a new ETS for-profit subsidiary in order to maximize the profits from the overseas market.

Moreover, TOEFL not only used international EFL tests, but also diversified its products. In September 2005, the ETS initiated classroom learning product, LanguEdgeTM Courseware, which can be accessed via a network server. Its price was set at a minimum of $550 for five computers. Another high-stakes product is the Institutional Testing Program, which is a short test based on TOEFL ‘retired versions.’37) Educational institutions can be licensed to administer this exam, costing $20 45 per person. Since the cost of the test is comparably low, this program is used as practice tests for many students preparing for the actual test. Pre-TOEFL is designed for students in introductory and intermediate levels of EFL learning. In short, the ETS profited from its high-stakes test in the overseas market, not only with the test itself but through the development and diversification of products, e.g., pre-TOEFL, Institutional Program, and computer based learning tools, and TOEFL preparation textbooks that are widely used all over the world.

[Table 3.] Gross Profit of Educational Testing Service (ETS) in 2007

Gross Profit of Educational Testing Service (ETS) in 2007

The ETS has been criticized for being a highly competitive business operation and acting as a multinational monopoly in the guise of a nonprofit institution. Due to its legal status as a nonprofit organization, the ETS is exempt from paying federal corporate income tax on a large proportion of its operations. While it does not have to report financial information to the Securities and Exchange Commission, it provides annual reports of detailed financial information to the IRS on Form 990 public available.38)

At the national level, the Americans for Educational Testing Reform (AETR) claims that the ETS violates its nonprofit status through excessive profits, executive compensation, governing board member pay, by directly lobbying legislators and government officials, and refusing to acknowledge test-taker rights.39) Because a monopoly on testing itself is power, the people or institution who create the test are responsible for the social consequences of the test, with ethics of the test should always be considered as the most important criterion for the proficiency tests.

4. Power Structure of the US Foundation?ETS?Universities?US Government

This study focuses on linguistic power structure based knowledge to better understand how the US government and the ETS cooperate with each other to penetrate US norms and values in South Korea. The strength of linguistic power is based on the premise that the nation or organization which possesses the linguistic power can change the range of choices open to others without putting pressure on them to make a decision or a choice. In other words, power based on knowledge is less visible so that the power base can make others follow its ideas without intentionally putting pressure on them.

In the previous sub-section, the cooperation of the US foundations, universities, and ETS with the US government were examined to provide a basis of understanding of the mechanism of American linguistic hegemony.

Universities, research institutes, and private corporations compose a horizontal relation where there is neither a hierarchy nor restrictions among these actors, just like a ‘flat parachute’. However, the flat parachute does not function properly without a mediator The US government plays a role as a mediator to provide approved governance to each actor. However, while the government role should be disclosed, it is camouflaged just like the ‘invisible cords of the parachute.’

To sum up, the United States was able to enter into the global EFL testing market through the action of the ETS. This mechanism is based on the linguistic power structure of US foundations, ETS as its key actor, and US colleges and universities with the US government. In this context, the US government does not have to put pressure on other nations to follow its decisions but can use power structure created by the government-industry relationships.

18)Inderjeet Parmar, “American Foundations and the Development of International Knowledge Networks,” Global Network 2-1 (2002), pp. 13-30. 19)Ibid. 20)Ibid., p. 16. 21)Ibid., p. 14. 22)Allastair Pennycook, op. cit. 23)Randy Elliot Bennet, What Does it Mean to Be a Nonprofit Educational Measurement Organization in the 21st Century? (Princeton, NJ: ETS, 2011). 24)Lyle F. Bachman, et. al., An Investigation into the Comparability of Two Tests of English as a Foreign Language: The Cambridge-TOEFL Comparability Study (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995). 25)Ibid., p. 4. 26)Ibid., p. 5. 27)Ibid. 28)Ibid. 29)David Kaye, “Searching for Truth about Testing,” Yale Law Journal 90-2 (December 1980), pp. 431-457, cited from Allan Nairn and Associates, The Reign of ETS, The Corporation That Makes Up Minds: The Ralph Nader Report on the Educational Testing Service (Washington, DC: Ralph Nader Institute, 1980). 30)Randy Elliot Bennet, op. cit. 31)James A. Harris, Requirements for Federal Income Tax Exemption under Code Section 501(c) (3), retrieved 13 May 2011 from

Ⅳ. American Linguistic Hegemony and ETS in South Korea: A Case Study

Because of the high-stakes nature of the English proficiency tests and the apparent political intention for their support by the US government, it is important to show how this mechanism is actually practiced. To speculate on this dimension, we investigate via empirical analysis the case of South Korea in the reinforcement of American linguistic hegemony. South Korea was chosen as an example because English is not only geographically but also linguistically far from South Korea, the impact of American English is considered as a global standard, and the English proficiency test made in the United States is widely used in various occupational fields.

Today, English is central to the ongoing process of globalization through the rise of transnational corporations, increase in the numbers of international organizations, and the predominant use of English on the Internet.40) A tremendous amount of money has been spent on teaching and learning English. English-Medium Instructions (EMI) has emerged as one of the most substantive developments in Korean higher education. Most secondary schools, specialized high schools, and universities encourage the use of EMI in order to improve competitiveness in the global higher education market. Table 5 shows the summary of Korean English education and the impact of English as a global language.

English competence in South Korea is comparably low due to the following reasons. First, the status of English in Korea is a foreign language, rather than a second language. Therefore, while English is studied in schools and institutions, Koreans do not actively use English in their daily lives. Second, the TOEFL is overly emphasized as an indicator of academic achievement, so learning English is focused on test taking skills rather than actual use.

Even though the traditional role of English has not been that significant, American English is now changing the economic structure, the English education in the public sphere, and the cultural identity of South Korea. Empirical evidence suggests American hegemony is being reinforced by the US linguistic power structure of ETS-US foundations-universities.

1. The Socioeconomic Impact of American EFL Tests in South Korea: The Imbalance of National Spending

In South Korea, people invest a substantial amount of time, energy and money to prepare for English proficiency tests. Since Korean companies require their applicants to submit English proficiency test scores, e.g., TOEFL and TOEIC, taking the EFL test is considered an essential prerequisite for employment. However, there is often a clear disparity between the applicant’s test scores and their English proficiency. Even though people invest extensive time and energy on preparation, which are invisible human resources, the test results stand as the only indicator of one’s employment opportunity. Therefore, a socioeconomic imbalance, particularly in terms of national spending, is inevitably the result of the American EFL tests in South Korea.

Currently, a hot issue among South Koreans is the ‘

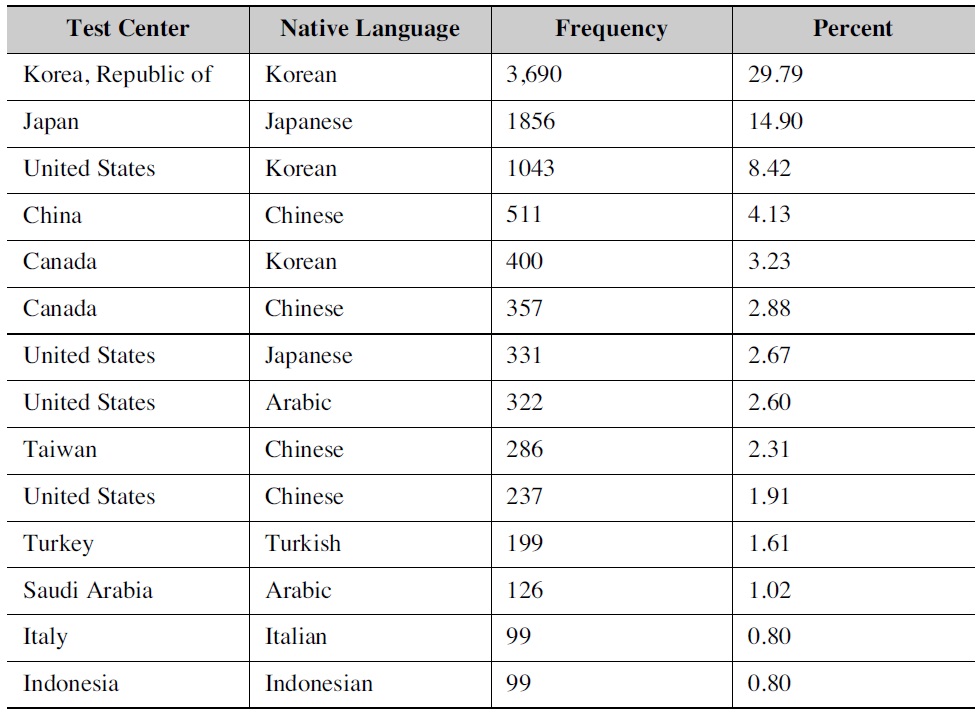

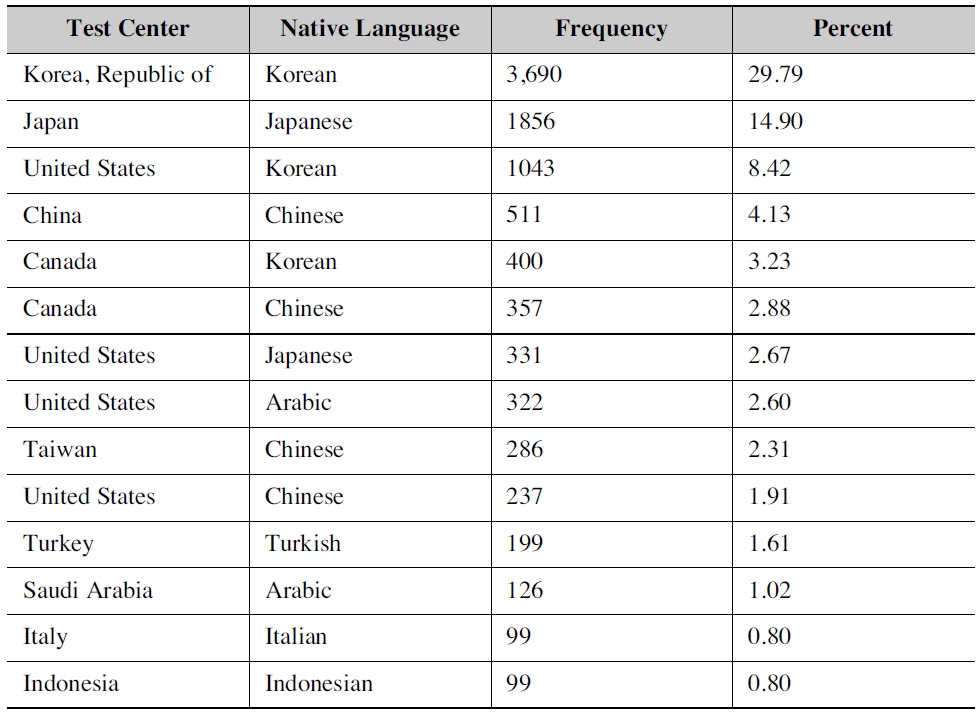

In addition, South Koreans are one of the largest groups of foreign students listed by the US immigration authorities. The US colleges and graduate schools mandatorily require foreign students to submit TOEFL scores in their applications, and all the government institutions and private companies require English test scores. It is not surprising that there is a high demand for opportunities to take the test. Table 4 shows the repeaters by test centers and their native languages. South Korea ranked first, third, and fifth among other nationalities and illustrates that Koreans not only take the test in their country of origin but also in the United States and Canada.

[Table 4.] Repeaters by Test Centers and Native Language of TOEFLⓡiBT 2007

Repeaters by Test Centers and Native Language of TOEFLⓡiBT 2007

According to the research conducted by the ETS in February 2008 based on ‘repeater analyses for TOEFL Ⓡ iBT’, the test performance of repeaters who took a second test within 30 days of their first test was examined for the period of January—August 2007. Consequently, only small changes were observed in the test scores between the repeaters’ first test scores and their second test scores. The author of this report concluded that “the information on repeater’s performance may help candidates make informed decisions about the need for repeating the test. The findings from the study suggest that TOEFL Ⓡ iBT scores appear to remain stable across test forms within the studied period of time. However, these findings constitute only one piece of empirical evidence about the stability and validity of the TOEFL Ⓡ iBT test scores.”42) This research not only shows the tentative empirical evidence of stability and validity of TOEFL Ⓡ iBT test, but also shows the fact that many testtakers from the East Asian countries, particularly from Korea, take the TOEFL test repeatedly with only marginal improvements in their test performances.

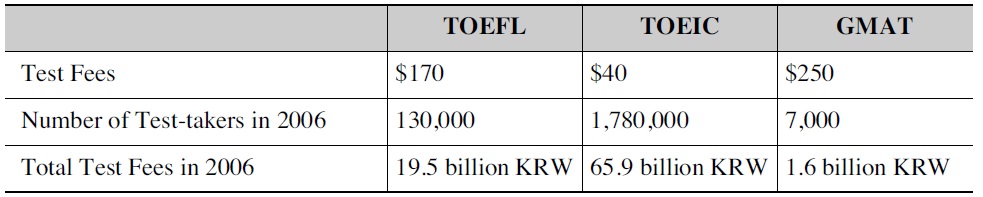

The number of people taking the test in South Korea jumped to 130,000 in 2006, from 50,311 in 2001. In order to take the TOEFL in 2006, Korean testtakers pay US $170 per test or the equivalent of 19.5 billion KRW. The primary purpose of taking the TOEFL is to gain entrance into US universities and colleges. However, the number of test-takers whose purpose is not to apply for the US universities and colleges, but to improve individual English competence in order to apply for specialized high schools or highly ranked universities in Korea and other countries is growing. Recently, specialized high schools, which were initially conceived to educate talented students in special areas, such as science, foreign language, art and so forth, are gaining great popularity among Korean students and parents.43)

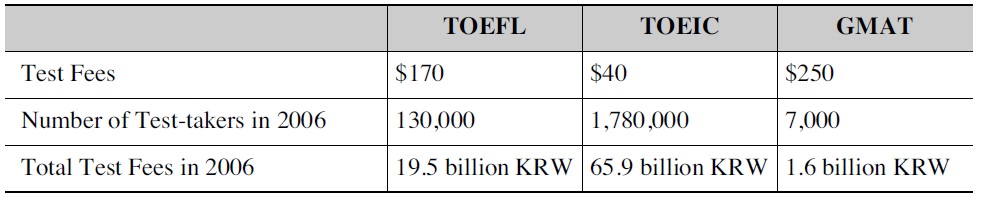

[Table 5.] The Individual and Total Test Fees of TOEFL, TOEIC, and GMAT in South Korea in 2006

The Individual and Total Test Fees of TOEFL, TOEIC, and GMAT in South Korea in 2006

Table 5 illustrates the characteristics of TOEFL, TOEIC and GMAT, provided by the ETS and the number of test-takers and test fees of each of the tests (2006). It takes 39,000 Korean Won, or approximately 40 US dollars, to take the TOEIC. For 2006, a total of 1,780,000 people took the TOEIC test at an approximate value of US $71,200,000.

2. The Washback Effect of American EFL Tests in South Korea

The penetration of American norms and values through the EFL test as a means of consolidating American hegemony is evident. As Modiano argues, “It is impossible to learn a foreign language without being influenced ideologically, politically, culturally, etc. The teaching and learning of a geographically, politically, culturally ‘neutral’ form of English, which is perceived as a language of wider communication and not as the possession of native speakers, is one of the few options we have at hand.”44) The EFL tests provided by the ETS do have a washback effect.

The washback effect can be defined as ‘the effect, positive or negative, of testing on teaching and learning’. The influence may be beneficial, for example, when a test leads to improvement of a syllabus of instruction and teaching. Negative washback may occur when the test inadequately reflects course objectives, but exerts an influence on what is taught.45) Lyle Bachman and Adrian Palmer consider the washback to be a subset of a test’s impact on society, educational system, and individuals. They believe that the impact of tests operates at two levels: the micro level, or the effect of the test on individual students and teachers, and the macro level, which considers the impact on society and the educational system.46)

3. Americanization of English Education

The majority of Koreans spend much time, energy, and money to take the TOEFL and TOEIC tests. In spite of all these efforts, why is it that they find it difficult to obtain productive and effective English skills? The primary reason is that they have to improve their test-taking skills with the aim of getting higher scores required for admission or employment rather than learning genuine English proficiency. Therefore, a test-driven English education rather than quality in proficiency is inevitable in Korea. The washback effect of the TOEFL and TOEIC tests will inclusively lead Korean education to be Americanized in terms of content, pronunciation, and learning materials.

To begin with, the TOEFL tests contain references on American culture, places, customs, and people. Raymond Traynor pointed out that the TOEFL has strong and even intense cultural bias in its test content.47) Since the TOEFL appears to be prepared with American norms and standards, American culture, places, customs, and people are naturally blended into the text. In his classifications, Traynor lists questions as American, non-American, and neutral. Examples are provided below:

Traynor argues that out of the 150 examination questions in the Practice Test of the official TOEFL Test Kit, 30 percent of the total questions can be classified as ‘American’. This means that a student with knowledge of American history, American geography, American sports, and other cultural backgrounds of America, would have an advantage to attain a better score. In short, questions in the TOEFL are about American individuals, places, events, objects, institutions, and customs, which favor unfairly those examinees that have spent a substantial amount of time in the United States.49) In other words, test-takers familiar with American culture and history have an advantage over those who are not. The ETS published a report that opposes Traynor’s view by asking “do foreign students who have lived in America for some length of time have more success on these kinds of questions than foreign students of the same relevant English language ability who come from the same regions of the world but have never lived in the United States?” Of course, we cannot generalize one’s language ability by length of time he/she spent in the United States or other English-speaking countries, but background knowledge or familiarity of the subject must exert positive effect to various degrees of exposure on test performance.50) For instance, the content of the items could deal with subject such as an anecdote taken from the life of a famous American; the architecture of American office buildings; the foraging habits of certain American animals; the characteristics of an American lake, seashore, or mountain; voting patterns in the US Senate; or the heights, weights, and longevity of American women.51)

The ETS may oppose the idea that considers the aspect that the TOEFL is designed for students who are willing to apply for American schools, so they have to obtain a certain level of American culture and history before taking the exam. Wadden and Hilke argue that reading passages are “similar in topic and style to those that students are likely to encounter in North American universities and colleges.” Moreover, the talk, conversation, and mini-lectures in the tests assume an actual model of language, and this model is the use of standard, idiomatic, and communicative North American English that students are likely to encounter in their daily lives.52) In addition, as former TOEFL developer Bonny Norton Pierce explains, the passages chosen for the reading section are not written for the TOEFL but drawn from “academic magazines, books, newspapers, and encyclopedias.”53) Therefore, the hypothesis of cultural bias in the TOEFL reading text is controversial. On the contrary, the person who chooses the text from the various academic magazines, books, newspapers, and encyclopedias, is an ETS test developer. The ETS test developers can therefore edit passages and skew the test with their own intentions. Also, the TOEFL is not only used as an indicator for college entrance, but also as an international parameter of English proficiency. The test requires knowledge of Americana, which is inequitable.

Fairness is one of the most important criteria in language testing. Fairness can be defined as free from favor toward any side.54) This definition suggests that a central focus of fairness in testing is the comparison of testing practices and test outcomes across different groups. The ETS has published an

Though the EFL tests contain various subjects about Americana, publication sets a clear guide to avoid criticism of using unfair and irrelevant geopolitical words and topics. For instance, military topics, regionalisms, religion, sports, are considered sources of construct-irrelevant variance in the United States.56) Knowledge of military topics such as conflicts, wars, battles, and military strategies are considered irrelevant to test English skills. Interestingly, imperialism is strictly restricted in use, because in some countries, the topics of imperialism and colonialism are considered inappropriate and offensive which can eventually upset the test-takers. Moreover, ETS test developers are told to use specific terminology such as “Chinese,” “Japanese,” and “Korean”, and not to use the word “Oriental” to describe Asian people, unless the word is quoted in historical, literary material, or used as the name of a specific organization.57) In this context, although there are clear guidelines for the ETS test developers to avoid sensitive words and topics that would bring international criticism, there are no such restrictions or guidelines on using American centric content in the EFL Tests. In this context, “The tests belong to ETS. So do the data. The control over what data are released, what research is carried out and reported, and ultimately what is tested and how, remains the province of the ETS staff.”58)

The most significant of all, when students prepare for the EFL tests, they consider the correspondence between the content of the standard test and what they have actually been taught. Therefore, students have to acquire information on American culture, history, geography, person, places, and so forth in order to achieve a successful outcome.

Second, the ETS itself offers a diversified package of ‘learning tools’ for its own exams. Many scholars describe a scale of ethical test preparation practices and criticize the textbooks published by the ETS on an unethical and indefensible scale.59) It is illegal to take all of the test materials provided by the ETS, and test-takers are not allowed to take notes on the test sheets in TOEIC. Even though there are hundreds of preparation textbooks for TOEFL, TOEIC, and other tests conducted by the ETS, they have to write the textbooks based on individual experiences of the test-takers or materials directly provided by the ETS. Only the ETS and the TOEFL and TOEIC programs know the answers, and TOEFL uses its own proprietary materials and ensures that the test version it releases possesses all the properties of actual tests.60)

Finally, due to the political context between Korea and the United States, American English has overwhelming effects in English as a foreign language education and testing. Watching Hollywood films and TV broadcasts has enormous impact on English acquisition. For example, the setting of the Hollywood animated movie

The ETS, however, has addressed counter criticism for using the American English accent in listening comprehension. When TOEIC assessment is developed to measure the ability to listen and read English, using ‘variety of contexts from real world setting’, the ETS only accounts for American English accent in listening comprehension. As a result, in 2008, ETS carried out a revision of the test that included major modifications.62) Of significance was the inclusion of a range of different English accents spoken in the United States, Great Britain, Canada, and Australia, which were added to the new TOEIC. This means that by modifying the range of English accents, the ETS intended to increase its test validity. Consequently, the test-takers may have difficulties distinguishing the meaning of the spoken word, with the result that test scores may vary compared to the previous TOEIC.

In short, the EFL tests such as TOEFL and TOEIC are so dominant in Korean society that several negative washback effects can be determined.

40)Mihyon Jeon, “Globalization and Native English Speakers in English Programme in Korea (EPIK),” Language, Culture and Curriculum 22-3 (November 2009), pp. 231-243. 41)Su-Hyun Lee, “South Koreans Jostle to Take an English Test,” New York Times (17 May 2007), available at

The TOEFL and TOEIC test results are the gatekeepers to higher education or better jobs in Korean society. At an individual level, English functions not only as a gatekeeper to positions of prestige in Korean society, but as a dominant international language. English also operates as a measure of social, economic, and political inequalities in many countries. The ETS is a nonprofit organization that administers the international EFL tests worldwide, and earns tremendous profit while taking advantage of tax-exemption under US tax laws.

This article examined the reinforcement of American hegemony via the ETS. In doing so, the theoretical framework of the US linguistic power structure an “upside-down parachute”—was adopted. The ETS, US foundations, and universities constitute the horizontal relations. There is no hierarchical order or restriction among these actors—i.e., ‘flat parachute’. However, the ‘flat parachute’ itself does not function except to maintain the status quo. Therefore the US government plays a significant role as a mediator of this structure.

American linguistic hegemony and its mechanism via the ETS have been veiled. When thing are to spread, they must normally mutate. (For example, if you wanted to start a McDonald’s store in India, what would you do? You could not serve beef hamburgers there because cows are holy and beef is taboo in Hinduism which is the religion of most people in India. McDonald’s stores in India now are popular spots because they serve chicken or mutton burgers, a great change needed to ensure the spread of this fast-food chain in a place whose cultural tradition is so different from the original country.) We simply cannot internationalize things and ideas without having them accommodate the customs and needs of people in their country who are supposed to use them for their own purposes.63) The organization such as the ETS is more powerful since it does not need any modifications or mutations according to the places whose culture is different from that of America. Therefore, the ETS does not appear to be hegemonic, since it provides intangible powers to individuals, but its incursion into geopolitics and economics can create inequalities that are unjustifiable.

63)Nobuyuki Honna, “English as a Multicultural Language in Asia and Intercultural Literacy,” Intercultural Communication Studies 16-2 (2005), pp. 73-89.