Ezra Pound has an idea of poetry as a field of energy in which words interact with each other with kinetic energy. What Pound creates by juxtaposing words and lines is the poetry of space or ‘field,’ in which all discrete elements are joined and interrelated not by the connecting wires of syntax but by images or energies they carry with them. The energy field which Pound creates in his poems is analogous to the theory of electromagnetism developed by Michael Faraday (1791-1867) and James Maxwell (1831-1879), who look upon the space around magnets, electric charges and currents not as empty but as filled with energy and activity. “Great literature,” Pound claims, “is simply language charged with meaning to the utmost possible degree” (

Particularly, the theory of electromagnetic field proposed by Faraday and Maxwell is applicable to Pound’s conception of “image” as well as to the stylistic characteristics of his poetry. Pound’s relationship with electromagnetism has been noticed by a few critics including Max Nänny, who, in

II. Words Charged with Energy: Lines of force

Well before Pound’s “Imagisme,” T.E. Hulme advised the poet to create “each word with an image sticking on to it” (78). Hulme’s vision of new language is echoed in Pound’s concept of “image,” which, for Pound, is not ornament but the essential ingredient of word. Meaning is embodied in the image, not expressed discursively in words. Pound called for a revolution in poetry in which “[words are] charged with a force like electricity” because “the thing that matters in art is a sort of energy” (

Therefore, “image” is filled with energy of potential meaning. Pound describes this potential within electromagnetic terms of positive and negative valences of force: positive charges repel other positive charges, and negative charges repel other negative charges, but positive and negative charges attract each other. Pound uses algebraic symbols to achieve a certain equation between the potential of words as the words interact one another with positive and negative valences. Pound uses the valences of -and + to illustrate the tension of the potential energy of poetry (

For Pound, image is “energy expressing itself in pattern” (

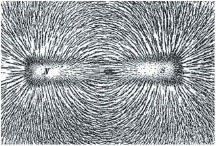

Faraday used the concept of ‘line of force’ to represent the disposition of electric and magnetic forces in space. There are magnetic lines of force as well as electrical lines of force, and that is the way one electrically charged particle attracts or repels another charged particle, and the same is true for magnets. The interactions between particles of matter are envisaged as interactions between centers of force or arrangements of powers diffused through space. Faraday shows that forces can only have relation to each other by curved lines of force through the surrounding space. The lines of force have real physical existence. Every point in space has a value and direction associated with it. Therefore, “[t]he field existing in the space between separated electrified bodies was to be distinguished from the [Newtonian] action of force operating directly between electrified bodies across finite distance of space” (Harman 72).

Pound’s “image” is now better thought of as a form produced by an energy, as iron filings shape themselves when magnetized. As we can see in “In a Station of the Metro,” each word is condensed with imagery and connected to other words in its immediate context to form what would be Faraday’s lines of force:

In the poem, the words charged with their own images or energies of positive or negative valence interact one another. The two complex lines of images are juxtaposed to create suggestive relations between them, where there is no rational conjunction or syntax. The elliptical or lapsed grammar however brings the two quite different planes into relationship with utmost speed and intensity, as we can see in some other examples, “Hugh Selwyn Mauberley” and “L’Art, 1910”:

Even though there is no logical transition from one line to the next, the omitted parts or space are charged with emotion and meaning as there are planes of relation being created between the lines. The two lines in each poem create a sort of electric or magnetic current or circuit as the images of the second line refer back to the first line, extending and completing it. All the three poems exemplified above obtain maximum energy and intensity not from the images in sequence but from the nodes of relationships created between them. They are constructed, Pound would argue, to “express a confluence of energy” like the design in the magnetized iron filings. The invisible lines of force, for Faraday, are themselves physical realities in space, which will suddenly appear when we sprinkle iron filings around a bar magnet. Therefore, poetry, for Pound, should capture “a world of moving energies . . . magnetisms that take form, that are seen, or that border the visible . . . these realities perceptable to the sense, interacting” (

In fact, Pound’s concept of “image” shares the same interests with Ernest Fenollosa’s ideogram. In Chinese written language, every word appears an image; the line is a succession of images. Meaning is found not so much in objects themselves but in the lines of relations or of force between them. As Dasenbrock rightly observes, “the essence of any situation” in Pound’s poetry “is a relation: for example, the faces in the crowd are related to petal” (108). The reason Fenollosa is so interested in Chinese characters is that they are pictures, not of things, but of processes and relations. Fenollosa offered Pound a way to see language in relation. According to Derrida, Fenollosa enabled Pound to see writing as an analogical system, where the ideogram, as a “collection of things or a chain of difference ‘in space,’” is inscribed within a linguistic chain (90). Fenollosa claims that “Relations are more real and more important than the things which they relate” (22). In Chinese characters, we cannot separate motion and things but see “things in motion, motion in things”:

Fenollosa’s aesthetics are also remarkably consonant with Faraday’s theory of field, which attributes physical reality to immaterial entities that are continuously distributed in space. The final word-view of Faraday is that “matter and force were identical and that the world was one vast field of force” (Berkson 149), the idea strikingly contrasted with the Newtonian concept of force as an action at a distance, the interaction of two material objects which are sharply localized in space.

III. Intellectual and Emotional Complex: Moving Electricity & Magnet

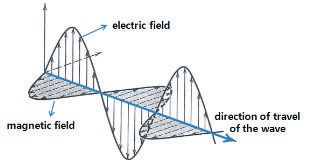

In his “Vorticism,” Pound revised his theory of image not as static image but dynamic vortex. Pound proposed “Vorticism” as a form or model of dynamic energy, distinguishing it from Amygism. What in Pound’s view is missing in “Amygism” is a sense of form to express dynamic energy. Pound’s vorticism is not a clean break from his early imagism but a type of return, with more dynamic energy and with a “stricter form of Imagism” (Jones 21). What Pound seeks to preserve is the dynamism inherent in Imagism as he has envisioned it: the image as a “radiant node or cluster” (“Vorticism” 469) charged with emotional, intellectual intensity. Pound attempts to create the kind of poetry that appeals to the reader by the effect of the vortex movement of intellectual and emotional charges, which, I will argue, is remarkably similar to the confluence of electric and magnetic fields that are coupled to each other as they travel through space in the form of electromagnetic waves. Neither an electrical field, nor a magnetic field will go anywhere by themselves. Unlike a static field, an electromagnetic wave exists only when a ‘moving’ magnetic field causes a ‘moving’ electric field, which then causes another moving magnetic field, and so on.

In ABC

Herbert Schneidau has given us the best definition of what Pound actually means by the emotional and intellectual complex: “the image of the Imagists is an attempt to combine the essentiality of the conceptual image with the definiteness of the perceptual image” (45). Pound attempts to write the poetry with a conceptual as well as perceptual dimension. It has been argued by psychologists that what was once considered separate areas as perception and conception have been reunited. Perception influences conception and vise versa. Goldstone and Barsalou point out that “conceptual processing is grounded in perception” and that “perception processes guide the construction of abstract concepts even when this direct link may not be obvious.” “Perceptual information plays a major role in conceptual knowledge” (232, 236). Pound claims that “musical property . . . direct[s] the bearing or trend of that meaning” (

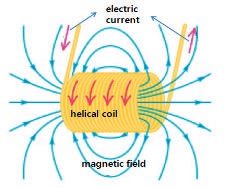

Pound’s concept of “image” as an “intellectual and emotional complex in an instant” is analogous to the interactions between electric and magnetic forces. Moving a magnet causes an electric current, and moving electricity creates magnetic field. “A continuous chain of creation is possible: A changing magnetic field will create a changing electric field, which create a changing magnetic field, which crate a changing electric field, and so on” (Spielberg 212).

If, for example, the electric current is directed along the wire of a tight helical shape, then the magnetic field inside the helix is directed along the axis of the helix, flaring out at the ends of the helix (Figure 2). Magnetic fields can be generated by electric currents. Depending on the configuration of the wire (how it is shaped), the magnetic field pattern can assume various forms. It is possible to simulate the field of a bar magnet by using a helical coil of wire to carry the current. It was the electromagnetic effects that led to the development of new types of energy conversion devices like electric motors, which convert electrical energy into mechanical energy. Magnetic forces on electric currents are the basic mechanism at work in electric motors and generators, and magnetic forces on moving electric charges are used to deflect the electron beam to make rasters, the highly refined dots, on television picture tubes (Spielberg 212).

The physical state of the electromagnetic field in which moving electricity creates magnetic field and moving magnet creates electricity can find its artistic demonstration in Pound’s poetry. The instant profusion of conception and perception, much like that of electric and magnetic fields, enables Pound to move beyond the sequential and linear hierarchy in time and space. “In a Station of the Metro,” for example, not only are the two images juxtaposed but are the two different dimensions of experience: perception and conception which influence and direct each other. Pound’s intention is to describe the exact moment in which the eye perceives an image and the brain conceives a concept. The first line, “The apparition of these faces in the crowd” is the instant of visual perception which is transformed by the second line, “Petals on a wet, black bough,” into metaphorical conception, or vise versa. The juxtaposed perceptual images involve the relation of the images by comparison or contrast. As Karl Malkoff puts it, we are invited to feel “the nearly simultaneous existence of both of these images, since to compare and contrast is a function of intellect, while the juxtaposition of images is a function of perception, involving not only intellect, but the sensory apparatus as well” (45).1 Pound proposes neither comparison nor contrast between the images, but he simply let them play against each other, so that the reader can experience the instant moment of illumination similar to what he experienced when he was inspired to write the poem.

1It is also observable that Max Nänny correlates Pound’s audio-Visual images to modern electricity which, according to McLuhan, involves man’s entire sensorium. Whereas the traditional print medium calls for the isolated Visual faculty, the new modern electricity calls for the unified sense life (24). The verbal “circuit” of conceptual and perceptual images, provided an adequate energy applied to it, generates instant illumination or “the total field of awareness that exists in any moment of consciousness” (McLuhan 85).

IV. Electromagnetic Waves at the Speed of Light

Maxwell was able to show that the changing electric and magnetic fields, which are constantly recreating each other, are also propagating or spreading out through space as shown in Figure 3. Maxwell supposed that electricity and magnetism are both aspects of the same electromagnetic force, and that this force, as they interact each other, travels in the form of electromagnetic waves.

Maxwell’s equations, which he developed to describe all electromagnetic phenomena, led him to an unexpected discovery that electromagnetic waves moved at exactly the speed of light, 186,000 miles per second. His equations show that visible light and electromagnetic waves are different manifestations of the same underlying phenomena. Light is nothing but an electromagnetic phenomenon. Later on, Maxwell’s electromagnetic waves, traveling at the speed of light, were physically detected by Heinrich Hertz in 1880, a striking confirmation of the electromagnetic field. Hertz was able to generate oscillating electric current at frequencies of a few hundred million vibrations per second. This led to the invention of radio and opened what Pound calls “the age of radio” (

The Maxwell’s identification of the electromagnetic and light might have allowed Pound a relativistic sense of escape from the limitations of Newtonian absolute time and space. Pound defines an image not as something subject to the finitude of conventionally understood time and space but as an “intellectual and emotional complex” presented “in an instant of time,” which gives him “that sense of sudden liberation; that sense of freedom from time limits and space limits”:

What underlays Pound’s sense of freedom is the concept of simultaneity. According to Einstein’s theory of relativity, there is nothing faster than light. Therefore, only at the speed of light can events be said to occur simultaneously. There is no sequence because there is no time: Time comes to a halt. Physical objects in space undergo a transformation when an observer travels at the speed of light. As Leonard Shlain points out in

Again, “In a Station of the Metro,” we can see that the poem is designed to transcend any geographical space and sequential time by rendering and juxtaposing images simultaneously. Pound places one concise perception next to another without a transition in a way that implicitly creates a connection. The discrete words or word-groups (or images) are juxtaposed with one another and perceived simultaneously. For Pound, the Image is instantaneous and simultaneous, and the space on the page is no longer subject to the sequential dictate of linearity. By juxtaposing discrete units of images simultaneously and by presenting “an emotional and intellectual complex in an instant of time,” Pound is able to break free of the limit of time and space. What is more, Pound juxtaposes the past and the present the way they comment on and illuminate each other. For example, his translations of Oriental poetry,

Pound’s creative process is emphatically temporal, breaking down the very distinctions between past and present. For him, the poetic perception liberates history from its chronological sequence. In

In the poem, there are three different Sodellos juxtaposed. Browining’s long poem

2The Vorticists like Ezra Pound and Wyndham Lewis explicitly rejected the Impressionists who tried to imitate nature’s most delicate effects of light and shade (Lewis 73). If the Impressionists like Cezanne and Gogh imitate the effects of light, the Vorticists attempted to capture the very essence of light in their arts. Pound asserts that one should not “allow the primary expression of any concept or emotion to drag itself out into mimicry” (Blast I 154).

Pound redefines the image as a vortex in his “Vorticism” and uses the word Vortex to state “every kind of whirlwind of force and emotion” (

Perhaps the most Vorticist poem of Ezra Pound is “Dogmatic Statement on the Game and Play of Chess.” In it, Pound composes a poem wholly along the vector lines of force cutting across the established black and white—or red and black—grid of the chessboard. Pound utilizes only the colors, shapes and angles of the movement of the chess game. There are not many verbs but a remarkable number of particles (such as “Striking” and “embarking”) which, according to Dasenbrock, give the poem “a greater sense of motion” (89). With its geometric board and moving pieces, this poem renders the effect of Vorticist painting:

Pound makes of the inanimate pieces a clash and collision of invisible vectors of force and energy, which creates highly energized nodes or clusters. The most important stylistic principle is the lines of force, the whirlpools of force, that hold the fragments together. Pound considers the Vortex as a principle of shape and energy, the organization of all the forces. Pound found it necessary to construct a model for the moving energy, corresponding to the actions of physics, that could extend as a comparative metaphor of the electrical and magnetic circular motion.

Pound makes of the inanimate pieces a clash and collision of invisible vectors of force and energy, which creates highly energized nodes or clusters. The most important stylistic principle is the lines of force, the whirlpools of force, that hold the fragments together. Pound considers the Vortex as a principle of shape and energy, the organization of all the forces. Pound found it necessary to construct a model for the moving energy, corresponding to the actions of physics, that could extend as a comparative metaphor of the electrical and magnetic circular motion.

When Pound describes the power of the Vortex, he refers to a “turbine” as a vortex-imaging machine. “THE TURBINE. All experience rushes into this vortex. All the energized past, all the past that is living and worthy to live” (“Vortex” 153-54). A turbine is an engine with vanes and buckets rotating on a spindle, which extracts energy from a fluid flow and converts it into useful work. A wind turbine, for example, is a device that converts kinetic energy from the wind into mechanical energy. The Vorticists like Ezra Pound, Wyndham Lewis, and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska thought that the artist’s subject matter should express “the energies of the Machine Age” (Materer 115). Wyndham Lewis asserts that the modern is inspired by “the forms of machinery, Factories, new and vaster buildings, bridges and works” (30). Lewis blesses the great ports of England as centers of restless energy, the relentless activity of turbines and dynamos; he blesses “English eyes” for their “fancy and energy” (

It is worthy to note that Pound was preoccupied with the aesthetics of machine in America.

Pound wanted to revolutionize poetry the ways in which it can be parallel not only to the style of modern machines but to the scientific ideas behind the machines, particularly electromagnetism developed by Faraday and Maxwell. Pound’s idea of poetry as a field of energy is comparable to the technology of the early 20th century and the electromagnetism the technology is based upon. Pound attempted to respond to and incorporated these new forces which were transforming society. In the late 19th and the early 20th century, scientific ideas overwhelmingly changed the world through technological applications. Almost all the appliances that we think of today as modern were invented in response to the availability of electromagnetic energy. Faraday’s dynamo unleashed the whole electrical appliance industry including electric ovens and electric refrigerators and so on. The technology associated with radio, made possible by Hertz’s discovery of ‘frequency,’ was explicitly based on Maxwell’s electromagnetic waves. Nänny rightly observes that Pound was fully aware of “‘the light in the electric bulb’ and ‘the [electric] current hidden in air or in wire’ fundamental to what he called his world ‘the electric world’ of today” (

When Pound speaks of his Vortex, he refers to such structure or form of energy as it flows or circulates in the field. Pound’s Vortex is like Maxwell’s mechanical ether, which is “an illustrative model rather than an ultimate physical explanation” (Harman 06). Pound presented the Vortex as a perfect yet convenient symbol of dynamic energy or image. The symbol is a harmless choice which works both for experts and the mediocre, and for “those who do not understand the symbol as such,” “the symbolic function does not obtrude,” “to whom, for instance, a hawk is a hawk” (