This study offers an alternate theory for the acquisition of arms to the collective goods theory, which is essentially a theory of arms acquisition.1) Our theory is deduced from structural neorealist principles, whereas the collective goods theory puts more emphasis on the terms of behavior within alliances, which are squarely based on interest and rational choice. Our structural theory of arms acquisition shows how structural forces at work shape and condition arms acquisitions for a particular country, much more than we are able to acknowledge. It supplements what is lacking in the collective goods theory of arms acquisition, namely the postulates of the structure part and the link between interest and structure.

Olson has argued that free-riding incentives encourage a smaller member to rely on the collective goods that the largest member creates.2) Applying this argument to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), Olson and Zeckhauser have shown that the United States had a disproportionate share of the defense burden compared to the rest of the members in NATO.3) The logic of their argument has also been applicable to East Asia, particularly Japan.4)

From a structural theory perspective, however, the disproportionate share of defense burden is an outcome of various interacting structural forces, among which bipolarity stands out. The polar competition between the United States and the Soviet Union was the most powerful structural determinant for the disproportionate share.

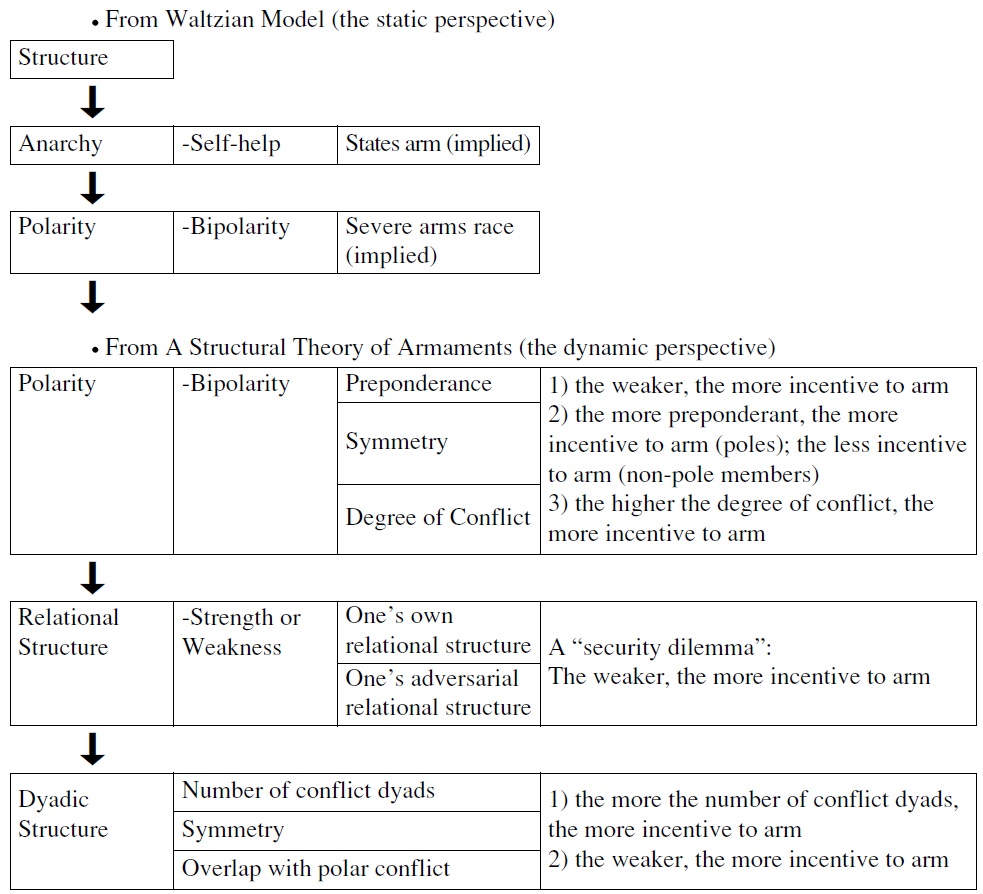

I intend to account for these disproportionate expenditures in terms of system-wide structure and polarity, as well as lower sub-systemic structures such as relational and dyadic structures. In the next section of this study, I examine the contentions of the collective goods theory as they account for a disproportionately high level of military spending by large polities, and then explain the assumptions of my own theoretical argument that bipolar systems and patterns of military expenditure are distinctive. I explain this in two ways. First, I show how the assumptions about systemic structure from the static perspective, such as that of Waltz, are supposed to determine state behavior. Second, I show how an extension of this logic accounts for military spending by the state and its acquisition of arms. Next, I consider the dynamic case. While the dynamic interpretation accepts the argument of the theorists of static systems that type of system accounts for some state behavior, the dynamic theory asserts something else as well: that it is the change in systems structure, especially change at critical points of nonlinearity on a state’s power cycle, that is most determinative of major war, and based on recent research, on military disputes as well. There is every reason to believe that the same dynamic structural impact holds for the effect on arms acquisition as well, which fits right into the theoretical conceptualization presented in this article.

1)In this study, the para bellum activities are the main focus of our discussion. The activities are denoted in a number of ways: arms acquisition, armament behaviors, military expenditures, defense preparations, etc. 2)Mancur Olson, The Logic of Collective Action (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1965). 3)Mancur Olson, Jr. and Richard Zeckhauser, “An Economic Theory of Alliances,” Review of Economics and Statistics 48-3 (1966), pp. 266-279. 4)See for example, Jennifer M. Lind, “Pacifism or Passing the Buck? Testing Theories of Japanese Security Policy,” International Security 29-1 (Summer 2004), pp. 92-121.

Ⅱ. The Collective Goods Theory of Arms Acquisition

The collective goods theory originally intended to explicate the problems associated with collective action, but it has naturally manifested to the study of alliances and arms. The path-breaking study of Olson and Zeckhauser has shown that a free-ride incentive was at play for the constituting states armaments in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Using Olson’s original thesis to argue that such collective goods as defense are provided suboptimally by any collective effort such as an alliance, NATO members allocated disproportionate amounts to defense of their respective gross national product (GNP). The argument is, in essence, twofold. The first argument is that the United States carried a larger share, while the rest carried suboptimal shares of the arms burden in NATO.5) In other words, the collective goods theory predicted that NATO members other than the United States would spend less on defense relative to their GNP shares within NATO, and the United States would spend more. The other is that among the NATO members, the larger members of NATO devote larger percentages of their GNP to defense than the smaller members, and vice versa; that is, the smaller members would devote smaller percentages of their GNP than the larger members.

On the surface, it appears that the two sides of the argument are plausible. In fact, there is no reason to doubt the logic of free-riding incentives and their role in NATO member’s efforts toward collective goods. Olson and Zeckhauser’s free-riding incentives and resulting disproportionality not only derive from endogenous factors, such as different sizes and valuations within NATO, but also result from exogenous factors, as seen in a systemic conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union. But the main focus of their arguments centers on the endogenous factors, whereas exogenous factors are treated as given or constant, as seen in their use of “a common objective” or “a common enemy.” Even in the treatment of the endogenous factors, Olson and Zeckhauser introduce many simplifying assumptions that limit the power of their model.6)

In this study, I do not intend to quarrel over the plausibility of those assumptions or their implications. However, it is necessary to point out the indeterminacies problem with the model. The most critical issue is the fact that not only exogenous factors codetermine states arms acquisition; interactions amongst variables arising from both exogenous and endogenous factors play a role in the armament behavior of states. In short, free-riding incentives and resulting disproportionality are, at best, contingent upon other variables than the size of the state.

The logic in bipolarity better explains why allies of the United States and the Soviet Union armed significantly less than the principal antagonistic poles. Structure is more of a determinate in explaining the free-riding incentives and resultant disproportionality than is the size within an alliance. The overwhelming preponderance of a pole does not by itself assure the full footing of the bill by the pole for the production and maintenance of a collective good such as deterrence, as argued by Olson and Zeckhauser. It does assure this when the element of preponderant power is combined with the logic of bipolarity, i.e., the pole is engaged in a systemic conflict. Furthermore, Olson’s theory is unable to account for variations or discrepancies, often calling for ad hoc explanatory measures as a result. Our structural theory of arms acquisition solves part of this problem by taking various structural variables into consideration.

5)Mancur Olson, Jr. and Richard Zeckhauser, op. cit., pp. 274-278. In the context of NATO, many studies have confirmed that there is a high correlation between allies’ defense burden and their rank in GNP. See Jacques M. van Ypersele de Strihou, “Sharing the Defense Burden among Western Allies,” Review of Economics and Statistics 49 (1967), pp. 527-536; Todd Sandler and Jon Cauley, “On the Economic Theory of Alliances,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 19-2 (June 1975), pp. 330-348; John R. Oneal and Mark A. Elrod, “NATO Burden Sharing and the Forces of Change,” International Studies Quarterly 33 (1989), pp. 435-456; John R. Oneal, “Testing the Theory of Collective Action: NATO Defense Burdens, 1950-1984,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 34 (September 1990), pp. 426-448; John R. Oneal and Paul F. Diehl, “The Theory of Collective Action and NATO Defense Burdens: New Empirical Tests,” Political Research Quarterly 47-2 (June 1994), pp. 373-396. 6)Four assumptions and their implications are well discussed by Olson and Zeckhauser. First, the costs of defense were constant to scale and the same for all alliance members. Second, a nation’s valuation of alliance forces obviously depends not only on its national income, but on other factors as well. Third, the military forces in an alliance provide only the collective benefit of alliance security, when in fact they also provide purely national, non-collective benefits to the nations that maintain them. And fourth, no alliance member will take into account the reactions other members may have to the size of its alliance contribution. Mancur Olson, Jr. and Richard Zeckhauser, op. cit., pp. 274-278.

Ⅲ. Structural Causes and Postulates

The discussion in this section is divided into two parts. First, I account for these disproportionate expenditures in terms of structure and polarity, on the basis of a Waltzian perspective. Our explanation contrasts sharply with the collective goods approach, which attempts to do so in terms of behavior within alliance.

Second, we expand Waltzian type of static perspectives so as to consider the dynamic case. Our dynamic interpretation of the impact of system structure on state behavior is somewhat different than the static interpretation. While the dynamic interpretation accepts the argument of the theorists of static systems that type of system accounts for some state behavior, the dynamic theory asserts something else as well: that it is the change in systems structure that is the most determinative of state armament behavior.

1. Arms Acquisition in a Waltzian Perspective

Armament behavior of states remains a lasting trend of states’ existence. Neorealists argue that anarchy, a distinguishing characteristic of the international system, gives birth to a security dilemma. This in turn provides a rationale for self-help behaviors of states. Arms and alliances are two of the most important means of self-help. A state can temporarily pursue security solely through one of these means, either arms or alliances; but in the long run, it uses a combination of the two.

The school of neorealism argues that polarity constitutes a layer of structural forces that, in turn, has logical manifestations that bind the behavior of the constituent states, both pole and non-pole members.8) In the post-World War II era, the balancing process predicted by the theory of balance of power between the United States and the Soviet Union gave birth to a peculiar structure: bipolarity.

Bipolarity requires the following conditions: (1) there must be two overwhelmingly superior states; (2) these two states are in a systemic conflict. Therefore, bipolarity means a constant zero-sum competition between two overwhelmingly superior states. Each pole aims exclusively to maximize the difference between its own and that of its opponent pole.9) Since small changes in the status quo can have symbolic importance, both of the poles must resist even small increases in the other’s capabilities. Their concern is their relative positions, not only in the military competition, but also in the political, economic, and cultural competition worldwide.

The fervent competition between the two poles has far-reaching implications. A competitive arms race is but one area of the competition. Due to the nature of the competition, the poles commit themselves to the selfgenerating cycle of arms-tension and to a feverish arms race.10) Each directs a significant portion of resources to armaments because, for them, no deterrence could work without preparedness of military strength, and no security could be guaranteed without deterrence. A “tit-for-tat” pattern operates in the armament game between the two poles. If a state is tightly security interdependent with another state, then the logic involved in the armament game is similar to an “action-reaction” cycle.11) To use Russett’s words, the two poles are the prisoners of insecurity.12)

In contrast to the poles, non-pole states, under the competitive logic of a bipolar conflict, have low motivation toward armaments. Peace is provided by the inter-polar deterrence. Although it is initially joint interests─among which a specific

When there is no need for their contribution to the production and maintenance of inter-polar deterrence, the choice open to the non-pole member is obvious—no urgency or enthusiasm toward armaments. Altfeld’s theory of alliance can help explain this with more force.13) He argues that the usefulness of armaments is an inverse function of the marginal productivity of alliances.14) With qualifications of our own, the argument can be stated as follows: under bipolarity, a non-pole state has fewer incentives to arm than to gain more wealth, if there is an increase in the marginal productivity of a polar cluster. In short, bipolarity, which is characterized by both preponderance and an inter-polar systemic conflict, presents the “free-riding” incentives for the non-pole states.

Our theoretical explanation is that the structure of bipolarity preordains a differential development of armaments between poles and non-pole members. The non-pole members’ incentive to arm is less attractive than the pole’s, as non-pole members are not motivated to balance militarily against the opposite pole, nor are they capable of doing so. Instead, the poles are required to balance off each other. That is, it is the individual interests of the poles to accumulate arms stockpiles due to the imperatives arising from the systemic inter-polar conflict, not the individual interests of non-pole members.15)

The logic in the theory of bipolarity does not provide a complete heuristic device by which incentive structures for the armaments of different allies can be deduced. It only tells that the relative power of each state is one of the most influential determinants for the base share of the total worldwide cost for military preparedness, i.e., the amount that one allocates to military preparedness is roughly proportionate to its relative power; the disproportionality in relative capabilities between poles and the rest and the severity of the systemic conflict between the two poles make the poles arm themselves relatively more than non-pole members, for they present “freeriding” incentives for non-pole members.

2. Dynamic Interpretation of the Impact of Systems Structure

The Waltzian application of bipolarity is nevertheless insufficient in providing explanations for the cases that deviate from the theoretical predictions. Some non-pole states obviously spend more on arms acquisition than the two poles; even among the non-pole members, some spend more, and others less than what the theory of bipolarity predicts, i.e., the amount that one allocates to military preparedness is roughly proportionate to its relative power.

We may not account for all the deficiencies, but we can make some cases explainable by taking more finite structural changes into consideration. At the level of polarity, we can investigate changes within bipolarity so as to trace characteristic patterns of arms acquisition. At sub-systemic level, we can look into changes in both relational and dyadic structures that impinge upon armament behavior. When we introduce varying characteristics into the concept of bipolarity, thus relaxing the assumption of bipolarity as a constant, we see some variations of structural forces that may mitigate the potency of the Waltzian proposition. Furthermore, if we expand our focus to subsystemic structural changes, many deviant cases become understandable.

1) Variables within Bipolarity and Armaments

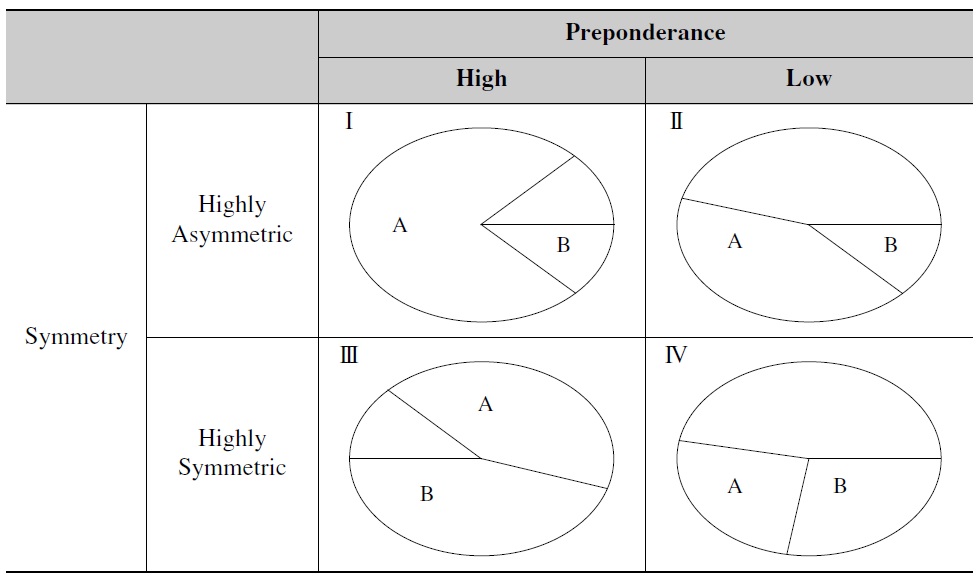

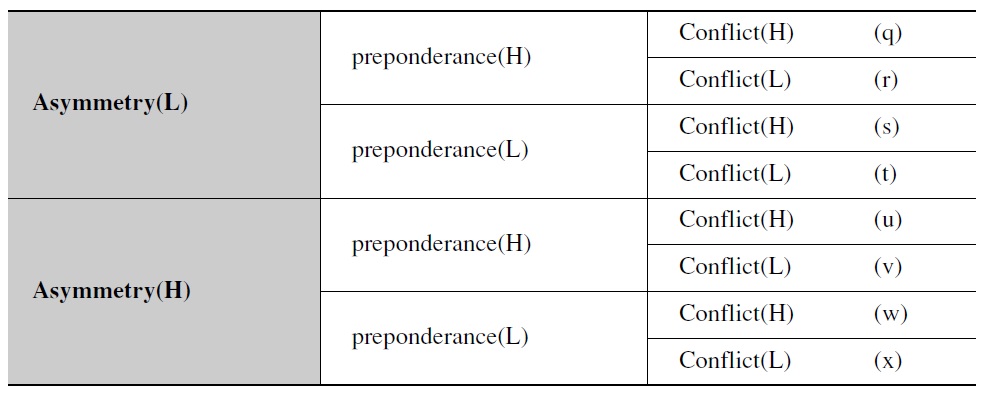

Bipolarity varies along the dimensions of preponderance and symmetry. To recognize the variety of bipolarity is in essence to admit changes in system structure. Figure 1 shows four ideal types of bipolarity, whose identity varies along two axes: symmetricity and preponderance.

Is it possible to hypothesize about the peculiarity of the structure and its relationship to arms acquisition? Yes, some characteristic patterns can be discerned. In the systems in Quadrant I and II, which display asymmetric inter-polar balance:

Because the two poles vie for dominance, the lesser pole is bound to be more burdened than the dominant pole. Since allies in the system in Quadrant I are limited in utility to both poles, they must resort to arms. In contrast, in the system in Quadrant II, both poles seek for allies whose contribution could make a difference in inter-polar balance.

What Olson termed free-riding incentives are therefore not a constant; they are greater for the allies of the dominant pole in the system in Quadrant I. But as the utility and availability of allies become more important in the system in Quadrant II, free-riding is no longer a safe haven. The fact that not only nonpole members could make a difference in polar balance, and that some of them are capable of increasing military capabilities, creates a permissive cause for more armaments.

In the systems in Quadrant III and IV, which display symmetric inter-polar balance, a structure-imposed imperative for arms acquisition for the lesser pole and its non-pole members disappears. But the system in Quadrant III is more prone to an arms competition between the two poles than the system in Quadrant IV is, for the utility of allies as stated above.

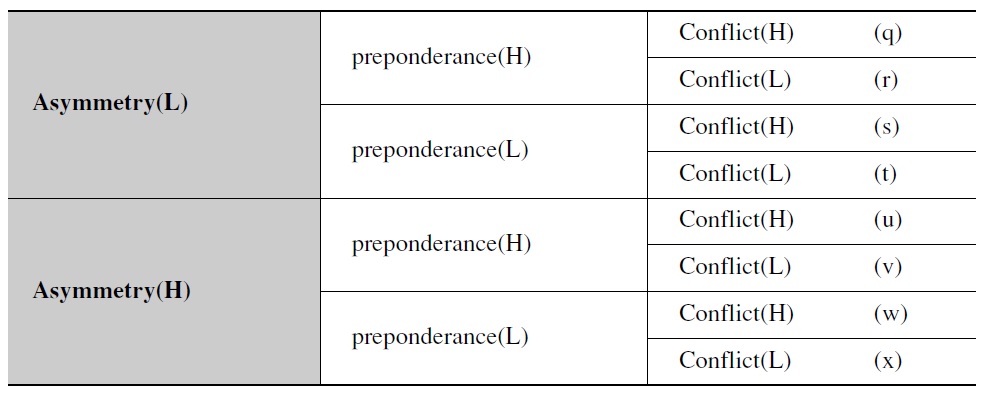

If we add two extremes of the intervening variable─either a high degree of inter-polar conflict or a low degree of inter-polar conflict─we now have eight different systems. Table 1 shows varieties of bipolarity. Eight systems differ from one another along the three dimensions. Although incentive structures are not definitive enough to make precise predictions about armament behavior of both pole and non-pole states, they show characteristic patterns?either higher or lower. We may use them for an interesting thought experiment. For example, if the severity degree of conflict is one of the most important determinants of armaments, then the higher the severity degree of conflict, the more the poles exert on armaments. That is, armament is a direct function of the severity degree of inter-polar conflict. Among the four possible systems, (q), (s), (u), and (w) wherein the severity of conflict is high, System (s) will be most prone to arms competition between the two poles; System (t) will be the least.

[Table 1.] Types of Bipolarity

Types of Bipolarity

In contrast, if the symmetricity of inter-polar balance deems to be the defining variable for armaments, Systems (u), (v), (w) and (x) would tend to exhibit more armament competition between the two poles than Systems (q), (r), (s), and (t). System (u) is the most prone to arms competition whereas System (x) is the least. By the same token, System (q) follows System (x); and System (t) is the most pacific amongst all, as far as arms competition is concerned.

2) Changes in Relational and Dyadic Structures

Our aim in this section is to incorporate relational and dyadic structures as part of structural forces that influence armament behavior. In incorporating relational structure, we relax the assumption of a direct one-to-one relationship of bipolarity-bipolarization. And by adding dyadic structures, we remove the last held assumption that sub-systemic structures do not intervene- in fact, structures extant in any two states are part of important structural forces, especially when the two states are security-interdependent.

Balance of power theory contends that when the weaknesses in the formation of the relational structure are created for a state, the state is to remedy them first by strengthening its links with friends or weakening the links that the enemy has with its friends. But when the remedy is insufficient to take care of the weaknesses, the state is likely to resort to armaments. Weaknesses in the formation of relational structure refer to the changes in the status quo of interstate relations in a way that either its projection of net power among friendly states against the adversary is diminished, or the adversary’s projection of net power among its friends is increased. The former occurs when a friendly state moves from the cooperation end to the conflict end in a cooperation-conflict continuum, either becoming neutral in the conflict with the enemy or defecting. The latter results from the gains of the enemy either by the subscription of new friends or by strengthening the links with existing friends; that is to say, a state is moving from the conflict end to the cooperation end in the continuum.

Some states do not have any adversarial relationship; others have one or more security-interdependent relationship(s). It is logically plausible that the greater the number of such relationships a state faces, the more likely the state is to resort to armaments. If a state is in a dire security-interdependent relationship with more states than one, the state is likely to put more efforts on military buildup. But this logical outcome depends further on the characteristics of the adversaries and the availability of a counterweight. Whether the adversaries are friendly or hostile amongst themselves is important. It is also important whether the state is capable of finding a counterweight by enlisting other friends.

As in the bipolar conflict, a dyad can vary according to symmetricity. The greater the degree of asymmetricity, the more the weak have structural incentives to arm. Since external strategies for a balance is almost always critical, this argument must be counseled against the polarity-related argument above. But overall, the logic involved in inter-polar symmetricity is applicable to symmetricity of dyadic structures, i.e., the lesser has to exert more on arms acquisition than the strong.

Whether the relationship occurs in isolation from, in intersection with, or in subsumption to the polar conflict is another significant dimension. The first instance is a sub-systemic conflict of a dyad completely unrelated to the polar conflict. Here, since the dyadic conflict is unrelated to the systemic polar conflict, polarity-related structures either positively or negatively affect the incentive structures. The second depicts a sub-systemic conflict of a dyad encroaching into the polar conflict: it has some issue areas unrelated to the overall polar conflict. Polarity-related structures sometimes matter, and at other times not. The third is a situation in which a sub-systemic conflict is always subsumed in the systemic polar conflict. Polarity-related structures inevitably enter into incentive structures positively.

Taken together, these dimensions manifest into various incentive structures facing the relevant state. It ranges from a state without any conflict dyad, even unrelated to the systemic polar conflict, to a state with multiple conflict dyads, extremely skewed in its capabilities vis- à-vis the adversaries’ to its disadvantage, as summarized in Figure 2.

3. A Structural Theory of Armaments

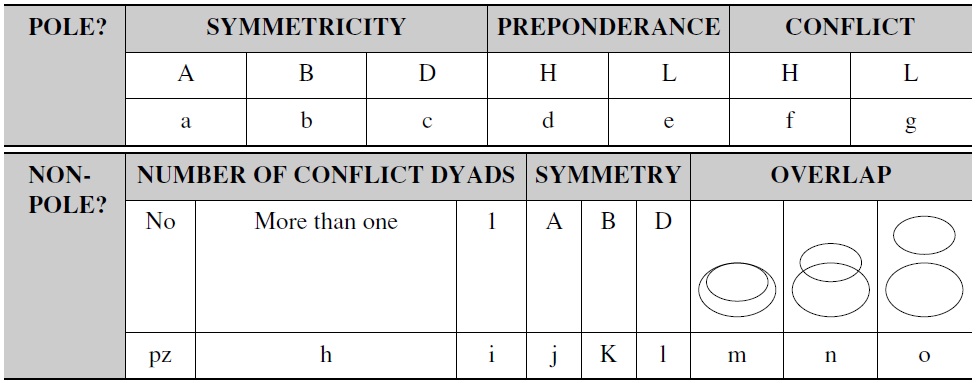

Polarity, relational and dyadic structures refine incentive structures for armaments as shown above. Figure 3 lays out possibilities of bipolar structural conditions with which likely dyadic structures interact. For the two poles, there are twelve possibilities; for the non-pole members, there are nineteen possibilities of dyadic structural conditions. They are combined to structure constraints and opportunities for each state─both the two poles and on-pole members.

In addition to the combinations of both polarity and dyadic structures, the concept of relational structures presented here further refines incentive structures. The occurrences of weaknesses in relational structures are theoretically plausible, for they supplement what is lacking in the concept of polarity─although I have endeavored to overcome the shortcomings of the concept by expanding into the various dimensions of polarity, the nature of the concept prevent the inclusion of interactive nature of power. It will be a valuable predictor for structurally induced armaments that polarity has all but omitted.

It is unnecessary to spell out each individual combination of bipolar structural conditions. Instead, I shall illustrate the structure of the theory by looking into one specific case. Assume that there are five states: A, B, C, D, and E, whose relative capability ratio is 100, 80, 5, 6, and 20 respectively. These five states constitute a system: A and B are engaged in a systemic conflict; A and C are allies, and B and D are allies; E is neutral in inter-polar conflict but part of a conflict dyad with D. Further assume that A faces a structural condition of adf, and C, a structural condition of pzo. Then, we can derive from the given that B faces a structural condition of cdf; D, ilm; and E, ijm. Thus, we have bipolar structural conditions in which A faces adf; B, cdf; C, pzo; D, ilm; and E, ijm, and a bi-centric relational structure with apparent weaknesses in the alliance system of B and D.

From the constitutive variables and their constraining effects, we can deduce the following: (1) structurally, A and B are prone to armaments; furthermore, B is structurally more burdened than A─weaker in terms of bipolar symmetricity and deficient in relational structure; (2) D’s incentives for armaments are triply stimulated by dyadic structure, weaknesses in relational structure, and inter-polar conflict; (3) structural conditions do not encourage C to arm─it is also conceivable that A extends its protection over C, which has a discouraging effect on C’s armaments; and (4) since E is tightly security-interdependent with D, it interacts with a “tit-for-tat” mold, but with dyadic symmetricity in its favor. A conclusion can be drawn from the incentive structures: the rank orders from the highest burden to the lowest, which is imposed by structural conditions for military efforts are either states D, B, A, E, and C, or states B, D, A, E, and C.

7)Kenneth N. Waltz’s theoretical framework advanced in Man, the State and War and Theory of International Politics, and those works that apply this framework, are collectively referred to as neorealism and here as a Waltzian perspective. See Kenneth N. Waltz, Man, the State and War (New York: Columbia University Press, 1954); Theory of International Politics(Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1979); and “Realist Thought and Neorealist Theory” Journal of International Affairs 44-1 (Spring-Summer 1990), pp. 21-37. 8)In terms of the most commonly used concepts in neorealism, the positional picture is expressed in the differentiation of poles and the others (non-pole members or neutral members). Polarity is defined as a systemic property for which the most significantly strong members (poles) in relative capabilities are accounted. Some use a substantively different definition of both pole and polarity. A pole is defined as a cluster of states; polarity is measured in relational terms. See Bruce Bueno de Mesquita, “Measuring Systemic Polarity,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 19-2 (June 1975), pp. 187-216; Michael F. Altfeld, “Measuring Issue-Distance and Polarity in the International System: A Preliminary Comparison of an Alliance and an Action Flow Indicator,” Political Methodology 10-1 (1984a), pp. 29-66; Richard N. Rosecrance, “Bipolarity, Multipolarity, and the Future,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 10-3 (1966), pp. 314-337; Michael Haas, “International Subsystems: Stability and Polarity,” American Political Science Review 64-1 (March 1970), pp. 98-123; Jefferey A. Hart, “Power and Polarity in the International System,” in Alan Ned Sabrosky (ed.), Polarity and War: The Changing Structure of International Conflict (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1985), pp. 25-40; David P. Rapkin, William R. Thompson, and Jon A. Christopherson, “Bipolarity and Bipolarization in the Cold War Era: Conceptualization, Measurement, and Validation,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 23-2 (June 1979), pp. 261-295; Frank W. Wayman, “Bipolarity and War: The Role of Capability Concentration and Alliance Patterns among Major Powers, 1816-1965,” Journal of Peace Research 21-1 (1984), pp. 61-78; Jack S. Levy, “The Polarity of the System and International Stability: An Empirical Analysis,” in Alan Ned Sabrosky (ed.), Polarity and War: The Changing Structure of International Conflict (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1985), pp. 41-66. 9)Arthur Stein, “Coordination and Collaboration: Regimes in An Anarchic World,” International Organization 36-2 (Spring 1982), p. 319. 10)Samuel P. Huntington, “Arms Races: Prerequisites and Results,” in Robert J. Art and Kenneth N. Waltz (eds.), The Use of Force: Military Power and International Politics, 3rd ed. (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1988), pp. 637-683. 11)Advanced originally by Richardson, the theory of arms race formulates an “actionreaction” cycle of armament behavior, which is based on one’s threat perception that arises from the other’s armament in a rival dyadic relationship, and thus causes the increase in armament. A “tit-for-tat” pattern of armament behavior is allegedly in operation as the increase in the perception of one pole’s anxiety over the increase of military preparedness of the other pole, in conjunction with one’s economic support base, influences one’s military preparedness level. This is the basic postulates of Richardson’s theory of arms race. See Lewis R. Richardson, Arms and Insecurity: A Mathematical Study of the Causes and Origins of War (Pittsburgh: Boxwood Press, 1960). 12)Bruce Russett, The Prisoners of Insecurity (San Francisco: W. H. Freeman, 1988). 13)Michael F. Altfeld, “The Decision to Ally: A Theory and Test,” Western Political Quarterly 37-4 (December 1984b), pp. 523-544. Altfeld advances a theory of alliances, but with a slight twist the theory turns into a theory of arms. His theory is based on the trade-off characteristics between autonomy and wealth. The theory of arms postulates that states rely more on arms in any one of four circumstances: an increase in the marginal product of armaments; an increase in the marginal utility of autonomy; a decline in the marginal utility of civilian wealth; [and] a decline in the marginal productivity of alliances. 14)Michael F. Altfeld, op. cit., 1984b, p. 524. Arms and alliances are two of the most important means to increase security. A state can temporarily pursue security solely through one means, either arms or alliances; in the long run, however, it uses a combination of the two. The selection of a combination depends on the cost-benefit calculation. Alliances and arms have both benefits and costs. In general, alliances can be formed quickly and without much sunk-costs. In particular, asymmetrical alliances can benefit the weaker partner, such as non-pole states, since a pole can aid various aspects of state capabilities through resources transferred from the stronger partner. But alliances can sometimes be a liability rather than an asset. Alliances can generate a loss of autonomy. Abandonment and “entrapment,” which is defined by Snyder as “being dragged into a conflict over an ally’s interests that one does not share or shares partially,” are also potential costs. Arms, on the other hand, assure self-reliance, generate autonomy, and avoid the risk of abandonment or entrapment. That being said, it takes longer to build arms, as well as a substantial amount of financial, material, technological, and human resources. Particularly in the case of many non-pole states, an economic structure which often lacks an industrial base, accumulated capital, and necessary technology deprives them of the capacity of even initiating weapons system industries. Even if a state is endowed with such resources, extraction and mobilization of them for the purpose of arms buildups may cause weakening of the economy. Implicit in the cost-benefit calculus is the recognition of the substitutable character of armaments and alliances. Morrow presents this in a formal way: (cost of alliances)/(efficacy of alliances in providing additional security)=(cost of arms/(efficacy of arms in providing additional security). See Benjamin A. Most and Randolph M. Siverson, “Substituting Arms and Alliances, 1870-1914: An Exploration in Comparative Foreign Policy,” in Charles F. Hermann, Charles W. Kegley, Jr., and James N. Rosenau (eds.), New Directions in the Study of Foreign Policy (Boston: Allen and Unwin, 1987), p. 135; Glenn H. Snyder, “The Security Dilemma in Alliance Politic,” World Politics 36-4 (July 1984), pp. 466-467; James D. Morrow, “Arms Versus Allies: Trade-offs in the Search for Security,” International Organization 47-2 (Spring 1993), pp. 213-217. 15)An anonymous reviewer has pointed out that the structural arguments at this level on armaments cannot be deduced from the system theory as such. Yet this study argues that polar balance (or, for example, when the poles are engaged in a zero-sum game) itself creates structural causes for both the poles and non-pole members. Polarity is a distributional systemic property. Please refer to Kenneth Waltz, op. cit., 1979, pp. 67-79. 16)Kaplan, who initially popularized the concept of polarity, had in mind that it is a mixture of the two levels, as exemplified in his construction of “tight,” “loose,” and “very loose” bipolar models of international structure. Also recall Ruggie’s comments on changes in dynamic density, which manifest into the possibilities of a structural change. Morton Kaplan, System and Process in International Politics (New York: Wiley, 1957), pp. 21-53; John G. Ruggie, “Continuity and Transformation in the World Polity: Toward A Neorealist Synthesis,” in Robert O. Keohane (ed.), Neorealism and Its Critics (New York: Columbia University Press, 1986), pp. 131-157.

Why do states arm the way they do? Since armament behavior is structurally influenced, the core of the argument advanced in this study is this: relative capabilities closely correspond to military capabilities. For example, if state A has 20% of the relative capabilities in the system, the state is likely to have 20% of the military capabilities of the system. The structural theory of national armaments under bipolarity starts from this base formulation. It proceeds further as other operating structural forces warrant various other deductions. From our base formulation, we can deduce that: (1) the more powerful a state is, the more absolute military expenditure (AME) it has; (2) the two poles have more AME than non-pole or neutral members; (3) it is likely that the poles bear much more burdens of armaments than the rest due to a systemic inter-polar conflict which dictates a stiff competition on multiple fronts especially on armaments; and (4) the two poles generally spend more in terms of relative military expenditure (RME) than the rest. Exceptions possibly exist in dyads that are characterized by tightly security interdependent relationships. Each pole is likely to subsidize military buildups in its bloc members, that is, the nature of a non-pole member’s armament program is contingent upon the extent to which it is included in inter-bloc or inter-polar conflict, and the provisions supplied by the pole have either encouraging or discouraging effects on the non-pole’s armaments dependent upon the threat perception it has. However, at a certain point subsidized protection changes into a collaborated effort in which some nonpole members share the cost of the production and maintenance of deterrence.

Our arguments included varying characteristics of bipolarity─varying according to asymmetry, preponderance, and the degree of conflict. In an inter-polar conflict that is asymmetrical, the weak have relatively more of the burden of military efforts than the strong: the lesser pole tends to commit more to military efforts than the dominant pole. When combined with nearly absolute polar preponderance, asymmetricity imposes more burdens on the allies of the lesser pole; the allies of the lesser pole do collectively more for the military buildups than the allies of the dominant pole.

When a bipolar structure with high polar preponderance and asymmetry gradually evolves into a bipolar structure with low power preponderance and asymmetry, many changes occur in the trend of military buildups: (1) the margin of differences in the magnitude between what the lesser pole exerts and what the dominant pole commits narrows; (2) differences of the magnitude between the two poles and the rest narrow; and (3) the AME portions of the non-poles increase in percentage. Subsidized portions in the non-pole members’ efforts by the pole decrease or, in some instances, disappear; instead, the issue of burden-sharing takes part in the relationship between the dominant pole and its allies.

Two caveats exist. One is the fact that, with power preponderance waning, activities to forge alliances, alignments and coalitions are often given more weight so that armaments become less prominent. This leads us to a different structural concept, namely relational structure. Some of the arguments above need to be counseled against the arguments developed with the concept of relational structure. The other caveat is the structures extant in conflict dyads must be taken into account because many states are subsystem-dependent. The two poles constitute a dyad as well, and the interactive nature of their relationship is the most critical in their behavior. Other non-pole members are also subject to structural forces within a dyad, especially for those that are intertwined in a security web─two particular states are security interdependent.

We also incorporated structural influences from relational and dyadic structures on armament behavior. The weakness created in relational structures causes relevant states to remedy them: first, by strengthening alliance resolve, and second, by weakening the adversarial alliances. In most cases, if the weaknesses are not overcome, the relevant states resort to armaments. This argument will supplement some of the anomaly from the projections of purely polarity-enticed armament behavior.

Dyadic structures also dictate states into a particular mold. Three elements are significant: the number and characteristics of dyad, symmetricity, and dependence on the inter-polar conflict. The greater the number of conflict dyad for a certain state, the more the state is likely to resort to armaments. When there are more than two adversaries, the characteristics of the relationship among the adversaries are also important. When a conflict dyad is highly asymmetrical, the lesser has disproportionately more burdens for armaments than the strong. Whether a conflict dyad is separate from the interpolar conflict or not also defines the intra-alliance relationships between pole and non-pole members.

Since the study of Olson and Zeckhauser, many articles have contemplated its value, mostly the collective goods theory’s fit to reality. If applied to the arms acquisitions of the Northeast Asian states, it turns out to be false, for many countries allied to the United States spent on the military more than or equal to the United States did.17) Structural postulates drawn from polarity, relational structure, and dyadic structure can easily explain away these phenomena. This study has tried to show that the collective goods theory, when applied to arms acquisition, is alone insufficient in explaining freeriding incentives and resulting disproportionality. It has done this by showing structural logic for disproportionality, which has been assumed away by the collective goods theory. In addition, we have tried to overcome the inherent rigidity in neorealism. By introducing structural variances within bipolarity, and taking into account other structural levels, we proposed a more dynamic theory of arms acquisition. In short, our effort serves, on the one hand, as a compliment to the collective goods theory, and on the other hand, as a more plausible set of postulates that can be used to account for the state arms acquisition and military spending.

In short, we have attempted to create a deductive, theoretical, essentially non-quantitative explanation for arms acquisition and military spending based upon structural and neorealist criteria. Our theory differs from the collective goods theory in that it goes beyond explaining a disproportionately high level of military spending by large polities. It is capable of providing explanations for the small states with a tight security interdependent relationship, such as South Korea and Taiwan. It is also distinctive in that the disproportionate expenditures are accounted in terms of structure. This contrasts sharply with the collective goods approach, which attempts to do so in terms of behavior within alliance. Our structural theory of armaments needs a serious companion that utilizes first- and second-image oriented approaches, including those that investigate interest, strategy, and process variables.18)

17)It requires a whole new essay to probe into the plausibility of the proposed theoretical propositions. But some assertions can easily be checked against the defense expenditure data of the Northeast Asian states in Table 2. First of all in 1989 the Soviet Union (SU) as a lesser pole had heavier burden on defense than the United States. One of the US allies, namely Japan, was the only one that followed Olson and Zeckhauser’s theoretical trajectory. The two Koreas and PRC and Taiwan exhibited a pattern that coincides with that of a dyadic security dilemma and that has been in some way affected by relational structures. 18)See for example, Sean Bolks and Richard J. Stoll, “The Arms Acquisition Process: The Effect of Internal and External Constraints on Arms Race Dynamics,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 44-5 (October 2000), pp. 580-603.