Lindberg and Scheingold argue that European citizens are generally favorable toward European integration but also indifferent to the European project because of the complexity of European issues.1) For many decades, this ‘permissive consensus’ enabled political elites to pursue integration independent of popular preferences.

However, more recent studies on public attitudes in Europe suggest that the permissive consensus is now declining. The process of the Maastricht Treaty ratification confirmed this hypothesis. In both the Danish and French referendums of 1992, popular support for the Maastricht Treaty was significantly lower than expected.2) These referendums showed a deep gap between the political elites and the public and that public support for further integration could not be taken for granted.3) Indeed, the process of ratification of the Maastricht Treaty posed the question of European Union (EU) legitimacy.4) The Maastricht experience forced political elites to accept that the Union should develop policy legitimacy for further integration, which depends largely on the support of its population.5)

Facing the growing need to develop policy legitimacy, EU member states have increasingly used referendums on European integration. Since the first referendum held in 1972, twenty out of the current twenty-seven member states have held EU referendums. Pointing out that most EU referendums have been held since 1992, Taggart notes that referendums have become more popular as the European integration project has become less popular.6)

On one hand, referendums are perceived as a means of legitimizing EU policy.7) This view is based on the participative characteristic of referendums: the European public participates directly in policymaking through referendums. Indeed, some studies find that states with provisions for referendums adopt policies that are closer to the wishes of the voters.8) In theory, referendums could strengthen democracy in the EU by giving Europeans a voice about integration process and holding governments more responsive to public preferences.

On the other hand, critics of this approach claim that referendums could not legitimize policy at the European level. As noted by Closa, referendums have only the function of legitimizing domestic regimes.9) The causes for calling a referendum on European issues are located in the domestic regimes. It is further argued that as long as a referendum is held inside the country, any European issue ultimately turns into a domestic one.10) Past experiences with European elections and referendums have confirmed this ‘domestication’ of referendums.

Thus, it is important to examine whether or not referendums on European issues are dominated by domestic factors in order to answer the question of whether they can be used as an instrument for securing European Union legitimacy. From the arguments mentioned above, we can assert two conditions which appear to be crucial in order for the European Union to gain its policy legitimacy through referendums. First, the context in which political actors hold a referendum must not be dominated by domestic factors. Second, voters who are consulted in referendums must express their opinion on the basis of their own decision in the European issue. Thus, it seems imperative to consider both the attitudes of political actors and the behavior of voters in referendums in order to examine whether or not referendums are framed by domestic context.

This study examines political actors’ motivation in calling an EU referendum and voters’ attitudes in EU referendum so as to determine which factors primarily frame the EU referendums. To answer this question, this article analyzes the two referendums held in France in 1992 and 2005. Analyzing the French case is important in two respects. First, like Denmark and Ireland, France has frequently used referendums on European integration. The French case could thus provide ample illustrations of referendums. Second, in contrast to Denmark and Ireland, where referendums are constitutionally required, France does not have a constitutional requirement. This means that, in France, the attitudes of political elites play an important role in choosing to call a referendum, whereas in the two other countries, the role of political elites remains limited.

The next section presents some theoretical framework on EU referendums and is followed by an examination of political actors’ motivations and voters’ behavior as seen in the two French referendums (in 1992 and 2005).

1)Leon Lindberg and Stuart Scheingold, Europe’s Would-be Polity: Patterns of Change in European Community (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 1970). 2)Mark Franklin, Michael Marsh, and Lauren McLaren, “Uncorking the Bottle: Popular Opposition to European Unification in the Wake of Maastricht,” Journal of Common Market Studies 32-4 (1994), pp. 37-59. 3)Daniela Obradovic, “Policy Legitimacy and the European Union,” Journal of Common Market Studies 34-2 (1996), pp. 191-221. 4)Finn Laursen and Sophie Vanhoonacker (eds.), The Ratification of Maastricht Treaty: Issues, Debates and Future Implication (Maastricht: IEPA, 1994). 5)Daniela Obradovic, op. cit. 6)Paul Taggart, “Questions of Europe: The Domestic Politics of the 2005 French and Dutch Referendums and Their Challenge for the Study of European Integration,” Journal of Common Market Studies 44 (Annual Review, 2006), pp. 7-25. 7)John T. Rouke, Richard P. Hiskes, and Cyrus Ernesto Zirakzadeh, Direct Democracy and International Politics: Deciding International Issues Through Referendums (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 1992). 8)Thomas Romer and Howard Rosenthal, “Bureaucrats Versus Voters: On the Political Economy of Resource Allocation by Direct Democracy,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 93-4 (1979), pp. 563-587; Elisabeth Gerber and Simon Hug, Minority Rights and Direct Legislation: Theory, Methods, and Evidence (La Jolla, CA: Department of Political Science, University of California, San Diego, 1999); Simon Hug, Voices of Europe: Citizens, Referendums, and European Integration (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003). 9)Carlos Closa, “Referendum as a Legitimatory Instrument in the Integration Process”[Democratic Representation and the Legitimacy of Government in the EC], a paper presented at the 22nd Annual Joint Sessions of the European Consortium for Political Research, Madrid, Spain, 17-22 April 1994. 10)Doug Imig and Sidney Tarrow, Contentious Europeans: Protest and Politics in an Emerging Polity (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2001).

Ⅱ. Referendums on European Integration

1. Referendums in EU Member States

There are two different models, among others, of democratic process at play in the European project: the representative model of democracy and the direct model of democracy. Referendum is one of the various forms of direct democracy, and the use of referendums to ratify European treaties, accession, and membership constitutes the evident example of the institutionalization of direct democratic practices in the EU.11)

One must note, however, that referendums are not the main instrument of democracy in EU member states. Most EU member states perceive referendums as supplementary to representative democracy and as an extraordinary instrument providing additional legitimacy in pursuing specific policy.12) Several member states such as Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom do not even have constitutional regulations on referendums. Moreover, according to the British constitutional tradition, referendums are not even compatible with parliamentary sovereignty.

Despite the secondary nature of referendums in EU member states, the role of referendums seems more and more important in European integration. Since World War II, European integration has been the most common subject matter for referendums.13) Since the first referendum on European integration was held in France in 1972, a total of forty-five referendums have been held on issues of European integration. In important domains, there is a move toward a model of direct democracy and away from representative democracy.14) Referendums are indeed being used at crucial moments of European integration. It was by no means a coincidence that ten EU governments announced their decision to hold referendums to ratify the EU Constitution.

With the increasing use of referendums, theoretical and empirical research on referendums has proliferated over the last decade. Several classifications of the referendums have been put forward by many scholars. However, in order to analyze both the motivations of political actors and the voting behavior in referendums, it is necessary to focus on two ways to classify the referendums.

First, according to the constitutional factor, referendums may be either required (mandatory) or non-required (non-mandatory).15) Required referendums are constitutionally required for certain issues. Required referendums cannot be avoided, given the constitutional or institutional provisions. Non-required referendums are initiated only at certain political actors’ demand. Second, referendums may be binding or non-binding, according to legal factors.16) In binding referendums, the government has to implement the policy chosen by the popular vote. In this case, citizens effectively have the last word in the ratification process, and rejection by citizens renders the ratification impossible. In non-binding (‘advisory’ or ‘consultative’) referendums, the parliament or government might not fully respect the outcome of referendums. However, it may be politically dangerous for political actors to ignore the will of the voters.17)

It is important to take into account these two ways of classification, because it has been argued that referendums of both types affect both the motivations of political actors who might call a referendum and the voting behavior of citizens in referendums.18) Among EU member states, only Denmark and Ireland have a constitutional obligation to call a referendum in the ratification of EU-level treaties. In ratifying the EU treaties, referendums in other member states are called at the discretion of political actors.

2. Political Actors’ Motivations

Political actors have no choice but to hold a referendum in the case of required referendums. The choice of whether or not to call a referendum occurs only in non-required referendums. That is, only non-required referendums are called at the discretion of political actors. Analyzing the motivations of political actors should thus be limited to the non-required referendums.

European integration provides ample examples of non-required referendums.19) Since the first referendum on European integration was called in 1972, out of a total of forty-five EU-related referendums, twenty-three were not constitutionally required but were called at the discretion of the incumbent government. In 2003, seven of the nine referendums held by the new entrants to approve membership were not required, and none of the four referendums held in 2005 for ratifying the EU Constitutional Treaty were required.20) As we shall examine later, the three EU referendums that France has held since 1972 were all initiated by its president.

The non-required referendums held frequently on European integration raises an essential question: Why do political actors (the government or president) choose to call a referendum rather than relying on a parliamentary vote? As has been pointed out, unforeseen outcomes might present obvious political risks for political actors, and the efforts required to obtain ratification through referendum might be superior to those for parliamentary ratification.

There are two competing approaches toward explaining the motivations of political actors who might choose to call a non-required referendum: The first is related to the domestic/strategic approach and the second to the European/institutional approach.21) The first focuses on strategic calculations at the domestic level, while the second emphasizes institutional factors at the European level that might lead to the decision of political actors.

The domestic/strategic approach comprises several arguments. The first argument suggests that the government use referendums to maximize the outcomes of negotiations.22) Governments with more severe domestic constraints are expected to be more influential in the bargaining process and thus have a greater impact on the negotiation outcomes. The second argument for strategic approach assumes that government holds a referendum to consolidate its own position.23) In this case, referendums are used as a tactical weapon by reinforcing the electoral position of the government or by creating divisions of the opposition. This type of referendum is often called a plebiscite. The third argument suggests that referendums may be held to pass treaties that would not otherwise be ratified.24) Referendums serve as an instrument for securing ratification in the absence of parliamentary majorities.

Alternative accounts are put forward by some scholars relying on a European/institutional approach. They emphasize that the decisions of political actors are more influenced by European factors than by domestic factors. First, the force of discourses in favor of referendums which have been developed in the European arena and the imitation of paths followed in other countries have an important influence on the choices of political actors.25) It is also argued that governments tend to call a referendum in order to be more responsive to the popular preference toward European issues.

Of course, all of these different reasons for holding a referendum play an important role in different contexts. However, many scholars are inclined to consider that, in the case of non-required referendums, politically strategic calculations are the most important motivation of political actors for calling a referendum.26) In contrast, Closa, without denying the importance of strategic factors, focuses rather on the importance of the role of institutional factors at the European level.27)

How do voters behave in a referendum called by political actors for diverse reasons? On which criterion do they vote in referendums? In recent years, particularly in the wake of the Maastricht referendums, much has been studied regarding this question. There are currently two main approaches for explaining the voting behavior in EU referendums: the ‘second-order election’ approach and the ‘issue-voting’ approach.

The ‘second-order election’ is a concept employed by Reif and Schmitt to describe the European parliamentary elections.28) In their view, the European elections are dependent on a domestic political context as long as the national political issues remain more important both to parties and to voters. This concept can also be applied to the EU referendums: voters behave in EU referendums not in terms of the European context, but in terms of the domestic context. Franklin et al. explained the result of Maastricht referendums by using this concept.29) They noted that supporters of government parties voted much more strongly in favor of the Maastricht Treaty than partisans of their opposition parties. According to them, national issues tend to dominate the campaigns, and voters thus have a tendency to consider EU referendums as a means of expressing their attitude toward the government or to follow the recommendations of national parties.

This approach is contested by some scholars who focus on voters’ attitudes and beliefs toward European integration itself. In particular, Siune, Svensson, and Tonsgaard,30) while contesting the argument of Franklin, Marsh, and McLaren,31) claimed that partisanship and government popularity have played no role in the outcomes of Maastricht referendums. The ‘issue-voting’ approach argues that voting behavior in EU referendums reflects Europeans’ broad attitudes toward European integration. In other words, referendum outcomes can be seen as a reflection of reasoned decisions made by voters about the future of European integration.32)

Much interest has been expressed in this question of whether Europeans really vote on the issue on which they are asked to vote or merely vote on the domestic political context. Hug and Sciarini attempted to answer this question by taking into account the institutional factors of referendums.33) They argue that voting behavior in referendums is intimately linked with the types of referendums. According to their account, in a non-required referendum, the government party supporters vote in favor of ratification, because they are well aware of the political calculations behind the government’s decision to hold a referendum. If this non-required referendum is binding, they are likely to vote even more strongly in favor of ratification, because of the possible political consequences of their negative vote. In a non-required and nonbinding vote, the partisans of government party appear also to be aware of the intentions of government; but given the fact that the outcome of the vote is not binding, they consider the referendum as an opportunity to vote on European issues or to punish the government for diverse reasons.

In the view of Hug and Sciarini, both institutional characteristics of referendums (required/non-required, binding/non-binding) and partisanship (supporters of government party or supporters of opposition parties) strongly affect voters’ behavior in referendums.34) Given the fact that the government makes the decision to call a referendum, it is no wonder that supporters of the government party vote more favorably for ratification than partisans of opposition parties do. Thus, it seems imperative to take into account the institutional factors of referendums in analyzing the voters’ attitude in referendums.

11)Paul Taggart, op. cit. 12)Carlos Closa, “Why Convene Referendums? Explaining Choices in EU Constitutional Politics,” Journal of European Public Policy 14-8 (2007), pp. 1311-1332. 13)Claes H. De Vreese, “Primed by the Euro: The Impact of a Referendum Campaign on Public Opinion and Evaluations of Government and Political Leaders,” Scandinavian Political Studies 27-1 (2004), pp. 45-64. 14)Paul Taggart, op. cit. 15)Markku Suksi, Bringing in the People (Dordrecht: Martinus Nijhof, 1993); Mija Setala, “Referendums in Western Europe: A Wave of Direct Democracy,” Scandinavian Political Studies 22-4 (1999), pp. 327-340. 16)Markku Suksi, op. cit.; Simon Hug and Pascal Sciarini, “Referendums on European Integration: Do Institutions Matter in the Voter’s Decision?” Comparative Political Studies 33-3 (2000), pp. 3-36. 17)George Tridimas, “Ratification Through Referendum or Parliamentary Vote: When to Call a Non-required Referendum?” European Journal of Political Economy 23-3 (2007), pp. 674-692. 18)Simon Hug and Pascal Sciarini, op. cit. 19)George Tridimas, op. cit. 20)Ibid. 21)Carlos Closa (2007), op. cit. 22)Andrew Moravcsik, “Preferences and Power in the European Community: A Liberal Intergovernmentalist Approach,” Journal of Common Market Studies 31-4 (1993), pp. 473-524; Gerald Schneider and Lars-Erik Cederman, “The Change of Tide in Political Cooperation: A Limited Information Model of European Integration,” International Organization 48-4 (1994), pp. 633-662. 23)Vernon Bogdanor, “Western Europe,” in David Butler and Austin Ranney (eds.), Referendums Around the World (Washington, DC: AEI Press, 1994), pp. 24-97; Simon Hug and Pascal Sciarini, op. cit.; Laurence Morel, “The Rise of Government-Initiated Referendums in Consolidated Democracy,” in Matthew Mendelsohn and Andrew Parkin (eds.), Referendum Democracy: Citizens, Elites and Deliberation in Referendum Campaigns (New York: Palgrave, 2001). 24)Laurence Morel (2001), op. cit. 25)Carlos Closa (2007), op. cit. 26)Vernon Bogdanor, op. cit.; Simon Hug and Pascal Sciarini, op. cit. 27)Carlos Closa (2007), op. cit. 28)Karlheinz Reif and Hermann Schmitt, “Nine Second-order National Elections: A Conceptual Framework for the Analysis of European Election Results,” European Journal of Political Research 8-1 (1980), pp. 3-44. 29)Mark Franklin, Michael Marsh, and Lauren McLaren, “Uncorking the Bottle: Popular Opposition to European Unification in the Wake of Maastricht,” Journal of Common Market Studies 32-4 (1994), pp. 455-472. 30)Karen Siune, Palle Svensson, and Ole Tonsgaard, “The European Union: The Danes Said ‘No’ in 1992 and ‘Yes’ in 1993: How and Why,” Electoral Studies 13-2 (1994), pp. 107-116. 31)Mark Franklin et al., op. cit. 32)Palle Svensson, “Five Danish Referendums on the European Community and European Union: A Critical Assessment of the Franklin Thesis,” European Journal of Political Research 41-6 (2002), pp. 733-750. 33)Simon Hug and Pascal Sciarini, op. cit. 34)Ibid.

Ⅲ. The French Case in Perspective, 1992 and 2005

In the preceding chapter we have examined the classification of referendums and some existing theoretical frameworks for explaining the political actors’ motivations and voters’ behavior in referendums. Now that we have seen the intimate correlation between referendum types presented here and the attitudes of both political actors and voters, we now analyze the cases of two French referendums held in 1992 and 2005. In analyzing the political actors’ motivations and the voters’ behavior in these French referendums, I rely on the theoretical framework examined above.

Since the creation of the Fifth Republic in 1958, France has held ten referendums in total. Referendums in France are often associated with the plebiscite tradition created by Napoleon the Third and enhanced by Charles De Gaulle.35) De Gaulle, who was not elected by universal suffrage, did not hesitate to frequently use referendums as an instrument of securing his own legitimacy.36) Throughout the history of the Fifth Republic, this instrument of direct democracy has contributed to strengthening the president’s own power by legitimizing a specific policy choice. And French presidents have always understood the power of the referendum.37)

French presidents have made good use of referendums whenever they needed political support. They have called referendums irrespective of their specific type. Thus EU referendums also have been used for domestic politics. Out of the ten referendums held by Fifth Republic, three were held on European integration in 1972, 1992, and 2005. As noted earlier, there is no legal requirement in the French Constitution to hold a referendum on the EU treaties.38) These three French referendums on European integration were thus non-required and binding, if we classify them.

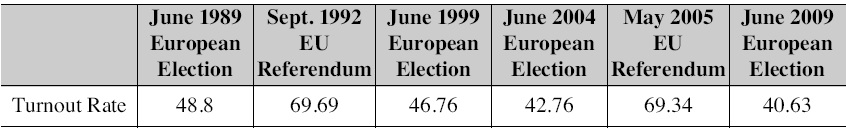

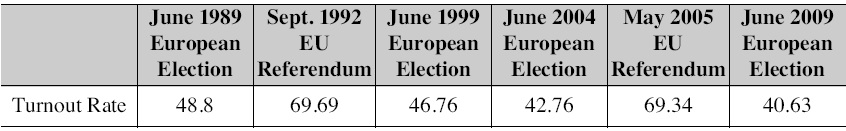

All of the EU referendums held in France have attracted considerable attention from the French public. In particular, both in 1992 and 2005, the French public showed strong interest in the referendums which could change the future of the EU. The turnout rate in EU referendums confirms the strong interest that French voters displayed in the EU referendums (Table 1). The difference is observable when we compare the EU referendum turnout with other European election turnouts: the former is higher than the latter. The turnout of around 70% in 1992 and 2005 was largely due to the intensity of the debates in both cases.39)

[Table 1.] Evolution in Turnout Rate in European Polls in France, %

Evolution in Turnout Rate in European Polls in France, %

On 20 September 1992, the French electorate voted 51% to 49% to ratify the treaty on enlarging the powers of the European Community agreed by the twelve member states at Maastricht in December 1991. The question asked was “Do you approve the draft law put to the French people by the President of the Republic authorizing the ratification of the treaty on the European Union?”40) On 29 May 2005, the French electorate went once again to the poll to vote on the issue of whether to support the adoption of European Constitution for the EU. The question that was set was “Do you approve the proposed law authorizing the ratification of the treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe?”41) This time, the French rejected the proposal, 55% to 45%.

Given the impact of the failed result of the 2005 referendum, some scholars argue that the 2005 case was totally different from the successful result in 1992. However, despite the contrasting results of the two French referendums, the two cases seem to show more similarities than differences.42) Similarities can be observed between the 1992 and 2005 referendums in many respects: situation, circumstances, political actors’ decisions, and voters’ attitude. A consideration of these similarities and differences between the two French cases would be instructive in understanding the patterns of political actors’ attitudes and voters’ behavior. In particular, in 1992, the leftwing party (Socialist Party, PS) was in office, while in 2005, the right-wing president called a referendum. These different but similar situations enable us to draw a more precise conclusion.

2. Political Actors’ Motivations in 1992 and 2005 Referendums

The three EU-related referendums held in France were all initiated by the president of the Republic. What forced the president to call a referendum whose result was unpredictable, rather than relying on the parliamentary ratification procedure in 1992 and 2005? In this section, I will attempt to answer this question by taking a closer look at the context in which the decision to hold referendums has been taken.

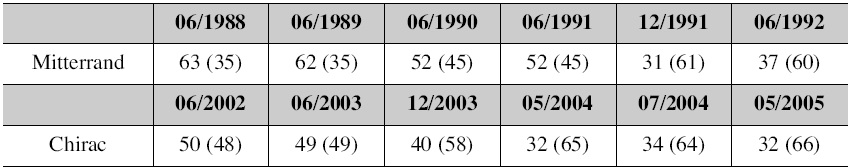

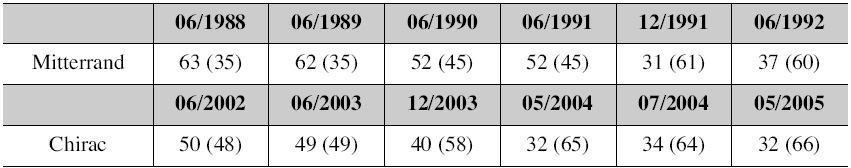

Before undertaking this task, the discussion calls for identification of some similarities between the backgrounds of the two cases. First, both Francois Mitterrand and Jacques Chirac were in their second term of office. In 1988, Mitterrand was reelected president by winning a victory over Chirac. In the presidential election of 2002, after seven years in office, Chirac secured a second term by gaining a massive second-ballot victory over Jean-Marie Le Pen of the FN (National Front). The second similarity is related to their low popularity. The economic situation was not favorable when Mitterrand and Chirac decided to hold a referendum. Especially, in 2004, when Chirac decided to hold a referendum, the employment rate reached 9% and a majority of the French people worried that the business conditions would be worse. This led to public dissatisfaction with the French president and Mitterrand and Chirac suffered lack of popular support at the time of the referendums. Table 2 illustrates the high levels of unpopularity they faced at that time. According to public survey, only 37% (in 1992) and 34% (in 2004) of the respondents were confident in the ability of the president to handle the economic problems. Facing this unfavorable social and political climate, Chirac had no choice but to rely on referendum which could help him tackle the difficulties. The third element of similarity between 1992 and 2005 is that the important elections were to be held in the nearest future: the general election due in March 1993 for Mitterrand and the presidential election due in 2007 for Chirac. These commonalities mentioned here appear to be crucial in explaining the reasons for which Mitterrand and Chirac decided to call a nonrequired referendum.

[Table 2.] Evolution of Popularity of the President, %

Evolution of Popularity of the President, %

We now examine more closely the two presidents’ choices, beginning with Mitterrand’s choice. Mitterrand’s popularity levels in 1992 were at their lowest.43) Hoping to end his presidency on a positive note, Mitterrand sought to improve his popularity levels. For him, a successful national referendum on a very important issue was the perfect opportunity to accomplish this purpose.44)

The second reason concerns his electoral strategy. Mitterrand sought to achieve significant political gains through holding a referendum, since his governing PS (Socialist Party) had experienced bad electoral scores since 1988. For example, in regional elections in March 1992, the PS was reduced to 18% of the vote. Mitterrand’s strategy was to create divisions among his political opponents (especially right-wing parties) and to attract the centrist voters.45) For his party, it was imperative to attract centrist voters (particularly centrist voters of the UDF [Union for French Democracy]), because the PS required additional votes to win the second ballot in parliamentary elections. These electoral considerations played a great role in Mitterrand’s decision to call a referendum. This was also the case for George Pompidou, who called a referendum in 1972 to ratify the enlargement of the European Economic Community (EEC) to Britain, Ireland, and Denmark. On this occasion, Pompidou intended to consolidate his own power through referendum by mobilizing his own camp and by dividing his opponents.46)

Moreover, Mitterrand perceived the Maastricht Treaty as an instrument both for reasserting France’s voice in European institutions and for weakening the dominant position of Germany in the European economy. Through the ratification of the Maastricht Treaty, he wanted to secure his place in history as a great French statesman.47) The Maastricht referendum was intended to serve these purposes. These factors considered, we can assume that, in the case of the 1992 referendum, the political strategic calculations played the most significant role in Mitterrand’s decision to hold a referendum in 1992. Of course, Mitterrand clearly indicated that the referendum had nothing to do with domestic political considerations.48) He indicated that voting for Europe was one thing and voting for him was another. But at the same time, this implied that the possible rejection of the Maastricht Treaty by the French should not be linked with his resignation.49) This can be interpreted as Mitterrand’s strategic detachment of his own position from the possible failure of the referendum.

The situation in 2005 was not very different from that of 1992. Chirac had been reelected president in 2002 by 85% to 15%. However, the vote in 2002 had been interpreted less as a vote for Chirac than as a vote against the FN (National Front)’s leader, Jean-Marie Le Pen.50) Thus, it was no surprise that the election results had not been favorable to the UMP (Union for a Popular Movement), Chirac’s governing party. The right thus suffered several electoral defeats in 2004. For instance, in June 2004, the UMP won only 16.64% of the vote. These outcomes stemmed from the growing unpopularity of both Chirac and Raffarin, which was largely due to the unfavorable socioeconomic situation in France. Given this low level of popularity, the political risks involved in calling a referendum were considerable, because the referendum vote could at any time turn into a protest vote.51) However, the referendum could also be used as an instrument for improving the situation. In this sense, Chirac seemed to remember Mitterrand’s strategy from 1992.52) Chirac intended to use a referendum to improve his popularity.

The electoral strategic considerations were also important for understanding Chirac’s choice. His decision to hold a referendum was aimed directly at reelection in the 2007 presidential election.53) For this purpose, Chirac sought to hold his centre-right rival, Nicolas Sarkozy, in check. Chirac also considered the referendum as a political opportunity to divide his opponents, particularly the PS.54) At that time, there was no consensus on the ratification of the European Constitution among left-wing parties. Chirac was aware that a referendum would be difficult and divisive for the PS. This led Chirac to hope to gain a major political advantage by aggravating divisions.

Apart from strategic factors, institutional or European factors might also account for each president’s decision to call a referendum. First, Mitterrand and Chirac could not ignore the fact that there was an obvious precedent for the referendum (1972 and 1992 EU referendums). This institutional constraint could partly influence a president’s decision to call a referendum. Second, discourses at the European level played an important role in the ratification process of the EU Constitution.55) Since 2003, the Convention which drew up the draft of the EU Constitution, has submitted several proposals in favor of ratification through referendum, or even pan-European referendum. Even though these proposals did not succeed, they influenced the national decision. They placed referendums on the agenda and they created a favorable climate within public opinion. Statistics show that 88% of EU citizens viewed constitutional referendum as indispensable or essential and that 76% of the French were in favor of ratification through referendum.56) Third, calling a referendum in member states might also influence the French president’s decision to hold a referendum.57) Tony Blair, who repeatedly expressed his unwillingness to hold a referendum on the EU Constitution during 2003, suddenly changed his mind in April 2004, and his decision might have influenced in particular Jacque Chirac, who came under pressure to take similar action in France.58)

But these institutional or European factors have some limitations in explaining fully the French presidents’ motivations. Even if public opinion demands strongly referendum choice, political actors would follow this line only when there is high possibility of victory. This was the case in 1992 and 2005, when the French were strongly in favor of the idea of European integration and agreed with the Maastricht Treaty (1992) and the European Constitution (2005). At that moment, they seemed decided to vote for ‘yes’.

Analysis of the two French cases confirms that, in both cases, the political actors’ decisions regarding calling an EU referendum were strongly related to political actors’ domestic tactical considerations. This empirical evidence shows that, out of the two theoretical approaches (strategic and institutional) presented above, the strategic approach appears to be more relevant in explaining political actors’ motivation for calling a non-required referendum.

The role of political actors is important not only in deciding whether or not to call a non-required referendum, but also in deciding when to hold it.59) The French case also illustrates that strategic calculations came into play in setting the timing of both the announcement and the vote on referendum. For example, Mitterrand’s strategy played a part in the successful outcome of the referendum.60) In 1992, the referendum was announced on June 3rd, the day after the narrow rejection of the Maastricht Treaty by the Danish voters, and was held on September 20th. Therefore, there was little time left for the opposition to organize an effective campaign. This was not the case for the 2005 referendum. This referendum was announced on 14 July 2004 and was held on 29 May 2005. Because of the amount of time between its official announcement and the actual vote, the ‘No’ camp was able to reverse the outcome of the referendum.61)

3. French Voters’ Behavior in the 1992 and 2005 Referendums

How did the French voters behave in the two EU referendums called by the president as a result of strategic calculations? Did they take into account the political actors’ strategies in voting in referendums, as has been argued by Hug and Sciarini?62) It seems reasonable to think that voters who are close to opposition parties are generally indifferent to the government’s propositions. We thus consider first the attitudes of supporters of the government party in order to answer this question.

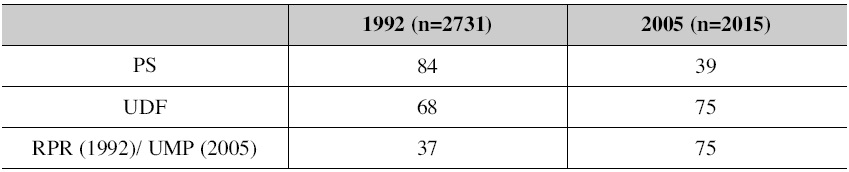

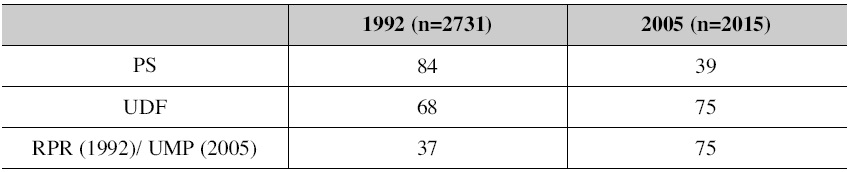

What was the voting behavior of government party supporters in 1992 and 2005? Table 3 shows the evolution of the percentages of three main parties’ supporters voting ‘Yes’ in two referendums in France. We can note here an important and decisive change between 1992 and 2005. According to exit polls, the PS partisans who largely supported the ratification in 1992 (84%) were much less in favor of the ratification in 2005 (39%). At the same time, the Rally for the Republic (RPR, later renamed the Union for a Popular Movement [UMP] in 2005), which persuaded only 37% of its voters to support the ratification in 1992 (37%), succeeded in mobilizing the massive ‘Yes’ vote in 2005 (75%). It is also noteworthy that, in 1992, the strongly pro-European UDF mobilized a less favorable vote than did the PS.

[Table 3.] Evolution of the ‘Yes’ vote percentages in the 1992 and 2005 referendums, %

Evolution of the ‘Yes’ vote percentages in the 1992 and 2005 referendums, %

All this data indicates that the partisanship has been the main factor conditioning voters’ attitudes in the EU referendums. That is to say, supporters of the government party voted strongly in favor of the issues on which they were asked to vote, whereas these same supporters tended in large part to vote against them when their party was in opposition. Then, what led the French electorate to vote differently according to the position of the party they support within the party system?

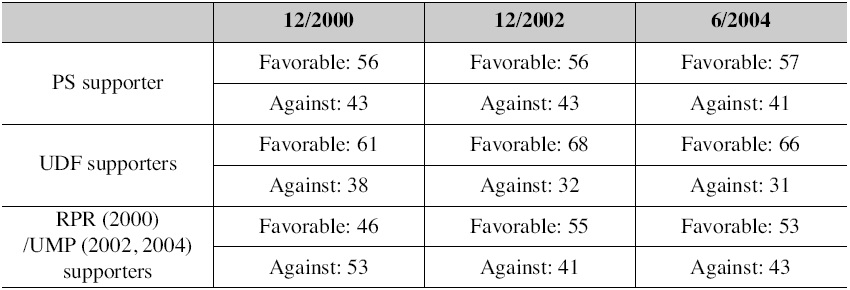

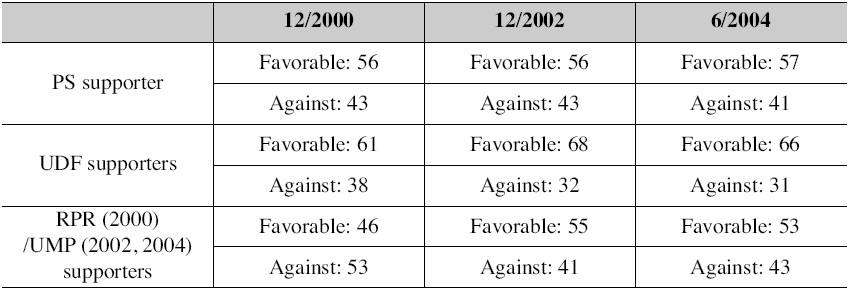

Before drawing a conclusion, one possibility must be examined: the UMP’s supporters might vote massively in favor of the ratification in 2005 because they largely supported the idea of European integration as a whole. Table 4 provides some data which reveals the development of public opinion over European integration during the period in which the European Constitution issue was not yet debated (2000 2002). If we consider the massive support for the EU Constitution in the 2005 referendum, we can expect a high level of support for European integration from partisans of the UMP. But according to opinion polls data, partisans of the UMP were not so favorable to European integration. This does not sufficiently explain the massive support (75%) that voters of the UMP demonstrated for ratification of the 2005 referendum. We can also note that voters of the PS were even more favorable toward Europe than those of the UMP.

[Table 4.] Public Support for European Integration, %

Public Support for European Integration, %

Furthermore, through historical evidence, it has been admitted that the support for the treaty was in general lower than that for the European integration as a whole.63) This was not the case for the UMP supporters in the 2005 French referendum. From this, we can assume that the strong support that the UMP voters gave in the 2005 referendum can be explained by the position of the UMP within the party system (government party). In other words, the UMP partisans were supportive of the decisions strategically made by President Chirac. Clearly, they were aware of the strategic considerations of Chirac and voted on the basis of their partisanship in the 2005 referendum. This logic can be also applied to the 1992 case: The PS supporters voted massively in line with the presidential wishes in the 1992 referendum.

Voting behavior of supporters from the opposition parties seems to be more complex. Unlike supporters of the government party, partisans of opposition parties are more at liberty to vote in referendums because they are less concerned about the government’s will: they vote either on the issue itself or on their partisanship. Their voting behavior is thus more unpredictable than that of supporters of the government party. Nevertheless, in France, in both 1992 and 2005, the majority of supporters of both the RPR (1992) and the PS (2005) voted ‘No’ in EU referendums. This is incomprehensible when we consider that the RPR and the PS officially adopted a pro-ratification stance in 1992 and 2005, respectively. This means that the majority of supporters of these parties did not follow the party lines when their party was in opposition.

Naturally, this leads us to ask why supporters of the opposition parties massively defected from their party line. Why did they vote strongly against the ratification? We can note here some similar phenomenon which occurred to the opposition parties, that is, the RPR in 1992 and the PS in 2005: intraparty dissent. Both the RPR in 1992 and the PS in 2005 were not united on the referendum issue and were seriously divided. This intra-party dissent on the referendum issue has not occurred in a government party, that is, the PS in 1992 and the UMP in 2005.

In 1992, the RPR was divided into two blocs: the top leadership of the RPR, including Chirac, sided with the ‘Yes’ camp, while two former ministers in Chirac’s 1986 88 government, Charles Pasqua and Philippe Seguin, both of the RPR, occupied the ‘No’ camp.64) Chirac, who aimed for electoral success, had no choice but to take the position on Europe compatible with the centrist voters. But Charles Pasqua and Philippe Seguin, who focused on the technocratic implications of the treaty and its threat to national sovereignty whilst maintaining their commitment to the Treaty of Rome and the Single European Act, took the anti-Maastricht Treaty stance.65) The intra-party dissent was more notable in 2005. The official party line of the PS was determined by an internal poll in December 2004, when 59% of the militants of the PS opted for the ‘Yes’ vote. But a minority of the leaders, especially Laurent Fabius, the deputy leader of the PS and a former prime minister, expressed their disappointment with the European Constitutional Treaty and campaigned actively for the ‘No’ vote.66) Fabius’ opposition to his party line was interpreted widely as a strategic move to challenge Francois Hollande, the First Secretary of the PS, for the leadership of the party and to become the main candidate of the PS in the 2007 presidential election.67)

Crum, who examined the behavior of political parties in referendums on the European Constitutional Treaty in 2005, put forward some conditions under which parties divide on European issues.68) According to him, opposition parties that side with the ‘Yes’ camp are more likely to be divided on European issues, because they are torn between pro-European ideological inclinations and strategic considerations as an opposition party.69) This intraparty dissent strongly influences attitudes of the partisans: rather than take cues from their preferred party, the supporters of an opposition party in which the elite opinion diverges are prone to deviate from the cues and adopt positions that are inconsistent with the official position of the party.70)

Indeed, the two French referendums in 1992 and 2005 confirm these arguments. In these two referendums, supporters of the parties in which internal divisions have occurred were strongly influenced by this dissent and did not consequently follow the party line. In particular, the 2005 French referendum case supports notably this interpretation. In 2004, when apparent divisions within the party did not yet occur, the supporters of the PS showed the high level of support for European integration in general as well as for the idea of the European Constitution. All this considered, we can assume that they voted massively ‘No’ during the referendum vote because they were influenced by this intra-party dissent.

The comparison of voting behavior in the two French cases shows how supporters of the government party as well as those of the opposition parties behave in EU referendums. This comparison has led to the following observations. Supporters of the government party perceive referendums as an occasion to express their approval of the incumbent government and consequently vote massively in favor of the ratification. This means that the argument of Hug and Sciriani, which claims that, in a non-required and binding referendum, the government supporters vote strongly in favor of the ratification because they are aware of the political calculations of the government in place and the political consequences of their vote are valid at least in the French situation.71) In contrast to partisans of the government party, supporters of the opposition parties, although they are more at liberty to vote, are inclined to vote against the ratification. This negative vote can be explained either by the partisanship factor for the supporters of opposition parties adopting an anti-ratification stance or by the intra-party dissent factor for the supporter of opposition parties adopting a pro-ratification position. In summation, voting behavior is largely framed by domestic political context and thus is far from the ‘issue voting behavior.’

35)Laurence Morel, “The Rise of ‘Politically Obligatory’ Referendums: The 2005 French Referendum in Comparative Perspective,” West European Politics 30-5 (2007), pp. 1041-1067. 36)Bernard Dolez, Annie Lauren, and Laurence Morel, “Les référendums en France sous la Vé République,” Revue Internationale de Politique Comparée 10-1 (2003), pp. 111-127. 37)Francesca Vassallo, “The Failed EU Constitution Referendums: The French Case in Perspective, 1992 and 2005,” a paper prepared for the First Annual Research Conference of the EU Centre of Excellence (EUCE) at Dalhousie University, Halifax, Canada, 21-23 May 2007. 38)Simon Hug and Pascal Sciarini, op. cit.; Paul Hainsworth, “France Says ‘No’: The 29 May 2005 Referendum on the European Constitution,” Parliamentary Affairs 59-1 (2006), pp. 98-117. 39)Sally Marthaler, “The French Referendum on Ratification of the EU Constitutional Treaty, 29 May 2005,” Representation 41-3 (2005), pp. 230-239. 40)Byron Criddle, “The French Referendum on the Maastricht Treaty September 1992,” Parliamentary Affairs 46-2 (1993), pp. 228-238. 41)Paul Hainsworth, op. cit. 42)Sylvain Brouard and Vincent Tiberj, “The French Referendum: The Not so Simple Act of Saying Nay,” PS: Political Science and Politics 39-2 (April 2006), pp. 261-268.; Francesca Vassallo, op. cit. 43)Francoise De la Serre and Christian Lesquene, “France and the European Union,” in Alain W. Carfuny and Glenda Rosenthal (eds.), The State of European Community, Vol. 2 (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 1993). 44)Francesca Vassallo, op. cit. 45)Byron Criddle, op. cit. 46)Ibid.; Vernon Bogdanor, op. cit. 47)Byron Criddle, op. cit. 48)Le Monde (3 July 1992). 49)Ibid. 50)Gérard Grunberg, “Le referendums Francais de ratification du Traité constitutionnel européen du 29 mai 2005,” French Politics, Culture & Society 23-3 (Winter 2005), pp. 128-144.; Paul Hainsworth, op. cit. 51)Gérard Grunberg, op. cit.; Sally Marthaler, op. cit. 52)Francesca Vassallo, op. cit. 53)Ibid. 54)Sally Marthaler, op. cit.; Paul Taggart, op. cit. 55)Carlos Closa (2007), op. cit. 56)Eurobarometer survey, 2003; CSA Poll data, June 2004. 57)Carlos Closa (2007), op. cit. 58)Ibid.; Paul Taggart, op. cit. 59)Sara Binzer Hobolt, “Direct Democracy and European Integration,” Journal of European Public Policy 13-1 (2006), pp. 153-166. 60)Francesca Vassallo, op. cit. 61)Ibid. 62)Simon Hug and Pascal Sciarini, op. cit. 63)Mark Franklin et al., op. cit. 64)Byron Criddle, op. cit. 65)Ibid. 66)Sally Marthaler, op. cit.; Sylvain Brouard and Vincent Tiberj, op. cit.; Gérard Grunberg, op. cit.; Paul Hainsworth, op. cit. 67)Paul Hainsworth, op. cit. 68)Ben Crum, “Party Stances in the Referendums on the EU Constitution: Causes and Consequences of Competition and Collusion,” European Union Politics 8-1 (2007), pp. 61-82. 69)Ibid. 70)Matthew Gabel and Kenneth Scheve, “Party Dissent and Mass Opinion on European Integration,” European Union Politics 8-1 (2007), pp. 37-59. 71)Simon Hug and Paul Sciarini, op. cit.

The goal of this article was to examine whether the EU referendums increasingly used by the member states are dominated by domestic factors. We have attempted to answer this question by analyzing the French case in terms of two factors: political actors’ motivations to call a referendum and voters’ behavior in referendums. The analysis of two EU referendums which were held in France in 1992 and 2005 led us to the following two observations.

First, in both 1992 and 2005, the political actors’ decisions for calling an EU referendum were strongly related to their domestic strategic considerations. In both cases, political actors used EU referendums mainly to strengthen their own position or to gain electoral advantages. Strategic calculations also came into play in setting the timing of both the announcement and the vote of referendum. Second, in non-required referendums strategically called by political actors, voters of the government party, whatever their attitude toward the issue at hand, strongly support the ratification whereas those of the opposition parties are prone to oppose ratification. In contrast to partisans of the government party, supporters of the opposition parties, although they have more liberty when voting, are inclined to vote against the ratification either because of the partisanship for the supporters of the opposition parties adopting an anti-ratification stance, or because of the intra-party dissent for the supporters of the oppositions parties adopting a pro-ratification position. This was evidently the case in both the 1992 and 2005 referendums. These findings clearly indicate that referendums on European integration are, throughout the entire process, intimately bound to domestic politics.

Given the fact that EU referendums are strongly framed by the domestic political context, we can assume that EU referendums cannot sufficiently secure the EU policy legitimacy. This conclusion is particularly valid for nonrequired and binding referendums. However, because the present study is limited to non-required referendum cases, it cannot, unfortunately, provide a satisfactory answer to the questions concerning the cases of required referendums. For required referendums, a different conclusion could be drawn. Thus, further research is needed to examine whether or not required referendums can sufficiently legitimize the EU policy.