This paper analyzes the tension on woman leadership between woman house churches and mainstream Presbyterian churches in Korea. What is the woman house church? There are Protestant Christians in Korea who meet regularly in private houses for a worship service. Most of them are lower-middle class women coming from different denominations mainly Presbyterians and Methodists, and they are active members in their churches. Thus, participants keep double membership at their mainstream churches and woman house churches. All leaders who take charge in the meetings are women despite a few male participants. They call the house meeting

Historically speaking, woman house church movement originated from the prayer mountain movement which has been a part of Korean Protestantism. The appearance and development of woman house church movement paralleled the rapid growth of Korean Protestantism. The woman house church movement shares the history of Korean Protestantism in the period of remarkable growth especially in 1970s and 1980s. The two streams of Korean Protestantism have remained parallel with each other while keeping their distinct features.2)

The woman house churches usually worship once per week during weekdays while some house churches provide worship services more than two times per week. The number of participants in these services ranges from 3 or 4 persons to more than 30. Services usually consist of two parts. Worship, which is longer than Sunday worship in mainstream churches, is the first part, followed by charismatic practices such as praying loudly together and healing practice follow the worship.3) Unlike mainstream churches, woman has an authority at the house churches, so woman particularly lay woman preaches at the worship. The woman house church constitutes itself an important part of Korean Protestantism but insufficient attention is being given to it.

Unlike the woman house church, in most mainstream Korean Protestant churches, women continue to be excluded from ecclesiastical office and from any decision-making process. Women in Korean Protestantism represent 70 percent of their numbers today, but they perform only supplementary roles. However, in woman house church, it is women particularly lay women who play dominant roles despite the existence of some male participants. The acknowledgement of woman leadership cannot but produce a tension with mainstream churches.

In this article, we analyze the tension that exists in regard to woman leadership between the two Korean Protestant, mainstream churches and woman house church. Through the analysis, we will argue that the tension between male-centered mainstream churches and female-based woman house church is related to the tension between male-centered Confucianism and female-based Shamanism in Korean society.

1)Woman house church is a gathering of women that takes place in a private home where people, mostly women, coming from different Protestant churches are held once a week or more. Depending on its location, members of the organized woman house church refer to their meeting place as “house altar.” For example, if a woman house church locates in Daebang Dong, they call the woman house church Daebang Altar (Daebang Jedan literally in Korean pronounciation). Woman house church differs from either the class meeting of Methodists or district meeting of Presbyterians, which meet weekly. Both share the common element of meeting at a private house; they differ because of participants. Participants of woman house church come from different Protestant churches mainly Presbyterians and Methodists, whereas people at those meetings of mainstream churches are from the same church. There are two kinds of woman house churches: organized and independent one. The organized woman house church has the center, Daehan Chrisian Prayer Hill (Daehan Sudowon in Korean, DCPH in this article), where the church originated, so we can capture the number and size whereas we cannot know about the independent woman house church, which has no organization. The number of organized woman house church has been increased continuously since 1965, the year of establishing the first of it. Through several visits to the Daehan Christian Prayer Hill, I was able to get information as follows. 2)In the history of Korean Protestantism, the prayer center movement began in the 1940s when Japanese colonial government suppressed freedom of Protestant churches. At that time, some Christians sought for places of seclusion individually in order to escape from Japanese control as well as to pray for the independence of Korea. However, it was after the liberation of Korea, 1945, that Protestant prayer centers appeared officially. Founders constructed buildings in the mountain for worship and pray. For the first time in the history of Korean Protestantism, sanctuaries for worship and prayer appeared in the mountain. Growth of the Prayer Centers in Korea Source: International Research Institution of International and Korean Religions (Seoul, Korea, 1989) 3)For this research, I interviewed with fifteen women in order to investigate why they join to the woman house church. All of interviewees had been active church members before they joined the woman house church. They decided to join for various reasons such as financial crisis, family problems, spiritual matters, and physical diseases. One common factor found in most of the responses is that their churches provided no help in hard situations. When they were in difficult situations, churches were not able to respond to their needs. To a new woman visitor, the woman house church becomes a shelter in which she is welcomed, where she tells her painful story to the members, and has the opportunity to listen to their stories. Through continuous participation and fellowship at the house church, the suffering woman gradually enters the stage of self-awakening through which she can figure out the meaning of her difficulties. In addition, she experiences holistic healing through which she can be cured physically, mentally, and spiritually.

Tension within Korean Society: Male-centered Confucianism vs. Female-based Shamanism

It was Japanese scholar Akiba Takashi who first explored Korean society as dualistic cultures in terms of gender-based religion: male-centered Confucian culture and female-based Shamanistic culture.4) His dualistic view has influenced many scholars who studied the relation of religion and society in Korea. Following the dualistic view, Laurel Kendall approaches the structure of the Korean household divided into two religious areas based on gender. She analyzes the

In a Korean household, Kendall observes the division of male-centered Confucian ritual and female-based Shamanistic ritual. Youngsook Harvey Kim, who studies Korean shamans, also insists that the architecture of Korean household is separated into two spheres: male and female.6) In terms of division, some scholars indicate, it can be assumed that Korean society as well as its households are separated into two spheres: male-centered Confucian culture and female-based Shamanistic culture.

Since the establishment of the

4)Kil-Song Choi, “Male and Female in Korean Folk Belief” Asian Folklore Studies vol. 43 (1984): 230. 5)Laurel Kendall, Shamans, Housewives, and Other Restless Spirits: Women in Korean Ritual Life (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1985), 26-27. 6)Youngsook Kim Harvey, Six Korean Women: The Socialization of Shamans (St.Paul: West Publishing Co., 1979), 255. 7)In 1392, the newly established Yi-Dynasty adopted Confucianism as its official religion in order to suppress Buddhism, the official religion of Koryo-Dynasty (918-1392 C.E.), the former kingdom. In 1945, with independence from Japanese colonialism (1910-1945), the new country chose Korea as the nation’s name remembering Koryo.

Before we delve into the tension of the two religions in Korean society, it is important to state the meaning of official religion and popular religion. It is Towler who attempts to classify religion into two types, official religion and common religion, based on their respective function in society.

According to Towler, common religion tends to provide alternative ways in the society where official religion plays a dominant role.9) Based on Towler’s concept, changing the “common” into “popular” in order to avoid misleading of the “common” with “ordinary,” scholars suggest classification of official religion and popular religion for general use for religious study. In a conference, Vrijhoff suggests a definition.

The distinction between official religion and popular religion is similar to that of institutional church and voluntary church in the circle of Christianity. Generally speaking, we can summarize distinctive characteristics of official religion vs. popular religion as religion of state vs. religion of individual, dominant vs. marginal, politically powerful vs. those without power, the educated or upper class vs. the uneducated or lower class, systematized and organized vs. not institutionalized.11)

Throughout the history of religion and society, we could observe a certain tension between the official religion and popular religion.12) The history of Korea is not an exception. Under the

As we have observed above, the newly established

Under

This discussion will now explore the views of woman within the two different cultures in Korean society.

>

Confucianism and the Korean Woman

Under Confucian system, loyalty to the king and filial piety to the parents plays an important role in sustaining social system. In order to strengthen the Confucian social system, it arranges the family system such that the father possesses supreme authority. Under the patriarchal Confucian family system, the father holds absolute power over family matters including the life and death of members of his own household.18)

Confucianism holds the theoretical principle that woman is inferior to man. The inferiority of woman functions as a basic principle for sustaining the Confucian family system in society such as

Confucianism built a system in which woman was segregated, and the segregation by gender became a pivotal tool of controlling woman.

As a result, silence was regarded as the most important virtue of woman. In addition, in order to control woman, Confucianism invented several devices such as “seven eligible grounds for divorce” and “woman’s three virtues of obedience.” 21) According to the rule on woman’s three virtues of obedience, a woman, through her whole life, must acquiesce to her father when she is young, to her husband when she is married, and to her son when she is old.22) In other words, woman should stay within a household under a man (father, husband or son) as his supporter or helper, nurturing the children of the man.23) Woman under the Confucianism of

8)Robert Towler, Homo Religious: Sociological Problems in the Study of Religion (London: Constable, 1974), 148. 9)Ibid., 150. 10)Pieter Hendrick Vrijhoff, “Twentieth Century Western Christianity” in Pieter Hendrick Vrijhof & Jacqjes Waardenburg eds, Official and Popular Religion(The Hague: Mouton Publishers, 1979), 226. In 1974, scholars held a conference on the concept of the official religion and popular religion at the University of Utrecht, Netherland. Nine scholars dealt with the classification of the concept within Christianity, and another nine explored the concept in other religions such as Judaism, Muslim, and Confucianism. They published their efforts in the conference, Official and Popular Religion. 11)Robert A. Segal, Book Review of Official and Popular Religion(The Hague: Mouton Publishers, 1979) in Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion vol. 21, no.3 (1982): 284. 12)Vrihjoff, 222. 13)Jong-Sung Choi, “Chosunsidae Yugyowa Musokeui Gwangye Yeongu,” [A Study on the Relation of Confucianism and Shamanism in Yi-Dynasty] Minjokkwa Moonhwa [Nation and Culture] vol. 10 (2001): 222. 14)Young-Taek Ji, “Shamanismi Hankook Gyohoee Kichinyounghyang,” [Influence of Shamanism to Korean Protestant Church” Nonmunjip[Collection of Works] vol.18 (1990): 207. 15)Chang-Sam Yang, “Shamanismkwa Hankook Gyohoe” [Shamanism and Korean Church] Hyunsangkwa Insik [Pheonomena and Understanding] vol. 10, no. 3 (1986): 58. In the early period of Yi-Dynasty, when Confucianism did not present itself as an official religion, Confucian officials requested the help of Shamanism like kut in that kind of crisis. However, after they established the Confucian social system, in the middle of Yi-Dynasty, they, as representatives of the official religion, tried to suppress Shamanism. Jong-Sung Choi, 241. 16)Youngsook Kim Harvey, Six Korean Women: The Socialization of Shamans (St.Paul: West Publishing Co., 1979), 3. 17)Jong-Sung Choi, 222. 18)Youngsook Kim Harvey, 255. 19)Hee-Soo Kim, “Roots of Han and Its Healing: A Study of Han from the Perspective of Christian Ethics” (PhD diss., Graduate Theological Union. 1994), 104. 20)Kwang-Soon Lee, “Korean Women’s Understanding of Mission-The Role of Women in the Korean Presbyterian Church” (PhD diss., Fuller Theological Seminary, 1985), 56-65. 21)Beginning under the Ching dynasty (1644-1912) in China, there have been seven grounds under which a man could arbitrarily divorce his wife: 1) If she behaves disobediently to her parents-in-law 2) If she fails to give birth to a son 3) If she is talkative 4) If she commits adultery 5) If she is jealous of her husband’ 6) If she carries a malignant disease 7) If she commits theft Since a divorced woman was rejected by her own family and her husband’s family, as well as by society, most women were willing to accept everything to keep their marriage, including accepting concubines. Andrew S.Park, The Wounded Heart of God (Nashiville: Abingdon Press, 1993), 55. 22)Ibid., 55. Originally the three virtues of obediences are in the teaching of the Classics of Rites, which is one of the Five Confucian Classics. Five Confucian Classics are Classics of Poetry, History, Changes, Rites and Spring and Autumn Annals. 23)Heung-Seok Nam, “Yugyoeui Yeosunggwankwa Hyundai Yeosungleadershipeui Moonje” [Confucianism s View of Woman and Woman Leadership Today] Dongbanghak [Study of East Asia] vol. 14 (2008): 291-292. 24)Hye-Sook Oh, “Gaehwagi Gidokkyo Yeosung Undong” [Women’s Movement of Korea in the Period of Modernization] (Master’s thesis, Berea Theological Seminary, 2004), 21.

Most scholars agree that Shamanism constitutes itself as basic layer of Korean culture and religion. It had existed before the fourth century C.E. when the major foreign religions such Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism were introduced to Korea.25) Shamanism has absorbed other religions, and transformed them as “Koreanized religions” as Youngsook Kim points out.

In Shamanism, it is the shaman who plays an essential role with the threefold function: priest, doctor, and fortune teller. The shaman presides various religious rites including

In contrast to Confucianism, women play a dominant role in Shamanism in terms of ministers and participants. Most shamans as well as clients are women. As Kim states: “Today, while there continue to be male shamans, the vast majority of shamans and their clients are female.” 28) It was women who experienced suppression under the male-centered Confucian society. Under the patriarchal Korean society, most women faced a bitterly difficult life which caused them to increase their

Tension within the two streams of Korean Protestantism, male- centered mainstream churches and female-based woman house church, is built upon the existing tension of the two different cultures within Korean society long before the arrival of Protestantism - Confucianism and Shamanism.

Now we will explore the relationship between two streams of Korean Protestantism and the tensions within the two cultures in regard to woman leadership.

25)Chang-Sam Yang, 56-8 26)Youngsook Kim Harvey, 8-9. 27)Ho-Jin Kim, “Hankook Gyohoe Chukbokshinangeui Mugyojeok Geukbokkwa Gidokkyo Gyoyookjeok Geukbokbangahn” [Shamanism’s Influence to Blessing Theology of Korean Church and a Suggestion of Overcoming the Influence] (Master’s thesis, Yon-Sei University. 2007), 14-20. 28)Youngsook Kim Harvey, 3. 29)Young-Taek Ji, 212. 30)Yong-Sik Lee, “Seongeui Sangjingsung, Mubokeul Tonghaebon Hankook Musokeui Kwonryuk,” [Sign of Gender: Observation of Korean Shamanism’s Power through Shaman’s Clothing] Shamanism Yeongu [Shamanism Study] vol. 3 (2000): 137.

Korean Protestantism, Confucianism, and Shamanism

Since the introduction of Protestantism to Korea, these two cultures, malecentered Confucianism and female-based Shamanism, have influenced the lives of Korean people, and Korean Protestants are not exceptions. Just as the male-centered Confucianism contributed to the formation of patriarchal mainstream churches, so female-based Shamanism connected itself to the rise of woman house church and mountain prayer centers, particularly since the 1970s and 1980s, the remarkable numerical growth period in Korean Protestantism.31) As we will examine further, the influence of Confucianism was tremendous in most areas of Korean society including mainstream Protestant churches. Thus, it is not difficult to observe the relationship of Confucianism with mainstream churches in their shared values, such as the patriarchal system. Likewise, female-based Shamanism has a relationship to the appearance of woman house church. Yee-Heum Yoon, professor of religious studies at Seoul National University, points out the close relation: “It is indeed surprising that Shamanistic practices seem to revive also in a certain trend of Protestant movement, namely

In the process of Christianization, especially the explosive numerical growth period in the 1970s and 1980s, the existing two cultures, patriarchal Confucianism and feministic Shamanism, infused the two types of Protestant churches, mainstream Protestant churches and woman house church and mountain prayer centers.33) In order to understand the connection between these existing two cultures and these two types of Korean Protestantism, in terms of women, we will explore woman leadership of mainstream churches and woman house church.

31)Confucianism has continued to be a dominant social system in Korea even after the arrival of Protestantism. Naturally mainstream Protestant churches exhibited patriarchal aspects due to the influence of Confucianism. Since the 1970s and 1980s, the numerical growth period, the Shamanistic culture emerged with the appearance and expansion of prayer centers in mountain and woman house church. Thus, we could observe the tension of the two Protestant groups, which reflected the tension of Confucianism and Shamanism. Further research will be necessary on the influence of Shamanistic culture on Protestantism before the 1970s. 32)Yee-Heum Yoon, “The Diversity and Continuity of Shamanism in Korean Religious History,” Shamanism Yeongoo [Shamanism Study] vol.3 ( 2000): 267. Ka-jeong jedan in Korean literally means house (or home) altar, which is the same woman house church in this dissertation. Therefore, Yoon already acknowledges the Korean woman house church. 33)Actually, mainstream churches had kept their Confucian culture before the growth of Protestantism. Due to the growth, woman house church began to appear as a new stream, so that we could see the two streams.

Woman Leadership in Mainstream Churches

In 2005, the believers of Confucianism reached only 0.2 percent of the total population in Korea. However, Confucianism has had a tremendous influence on the daily lives of Korean people. Though Confucianism lost its position as the official religion and ruling value system at the end of the

The male-centered culture of Confucianism influenced the emergence of the same dualistic realms, male and female spaces, in mainstream churches, so women continue to be excluded from important things just as they were in Confucian society. Moon-Jang Lee, a professor at Singapore Trinity Theological Seminary, points out on the discrimination of women in Protestant churches based on the dualistic roles of man and woman derive from Confucian culture:

In most Protestant churches, women take charge in subsidiary roles which ask obedience and sacrifices just as they do at home, like working in the kitchen. Despite their active contribution, women are excluded from important matters of their churches. Behind the discrimination against women, the influence of Confucian culture plays an essential role to the church. In other words, patriarchal structure of Confucianism penetrated directly into mainstream churches, so women could not be leader in their churches.37) In most mainstream Protestant churches, women perform tasks that are similar to the work they do in their homes.

Statistics from 1979, the period of numerical growth of Korean Protestantism, explains well the situation of woman leadership in mainstream Korean Protestant churches.

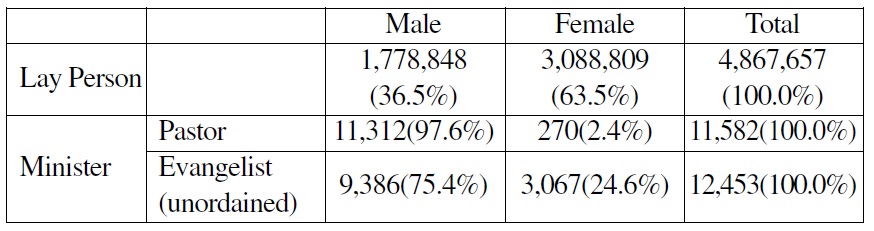

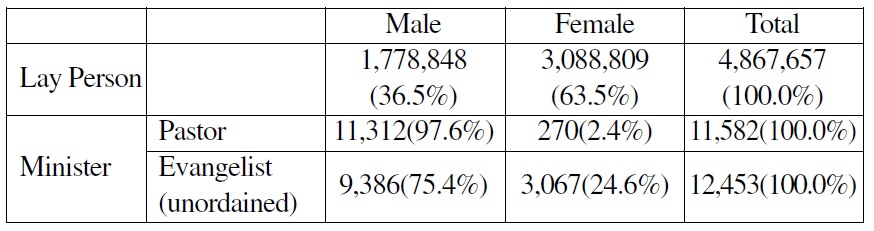

[Table 5-1.] Number of Lay Person and Minister in Protestant Church (1979)38)

Number of Lay Person and Minister in Protestant Church (1979)38)

In the table above, the number of women leaders was only 2.4 percent for pastors (

Women ministers are also discriminated against in terms of wages and tasks. According to one survey on the situation of woman ministers in 1988, 51.9 percent of women ministers received wages below 400 U.S. dollars, the minimum wage at that time. In addition, their tasks were house visitation (77.7%), Sunday school (5.0%), and preaching (3.3%), whereas male ministers worked mainly in preaching and education.40)

Women in male-centered mainstream churches play the same roles as women in the over-all Confucian Korean society. In regard to woman leadership, we can argue that patriarchal mainstream churches reflect the system and culture of Confucianism. Unlike mainstream Protestant churches, women in Korean woman house church and mountain prayer center, another stream of Korean Protestantism, perform active roles reminiscent of women’s roles in the Shamanistic culture.

Now we explore woman’s role in woman house church, especially considering its common features with Shamanism.

34)Jae-Kwang Gye, “Yugyo Munhwaga Hankook Leadershipe Michin Yeonghyang,” [Influence of Confucian Culture to the Formation of Korean Leadership] Shinhakkwa Shilcheon [Theology and Praxis] vol. 22 (2010): 85. 35)Jeong-Sook, Jeong, “Bokeumseoreul Tonghaebon Yeosungkwankwa Onelnal Hankook Gyohoeeuk Yeosung” [Women in Gospel and Women in Korean Church Today] (Master’s thesis, Hanil Presbyterian Theological Seminary, 2006), 65. 36)Moon-Jang Lee, “Bokeumkwa Munhwa Georigo Yeosungeui Wichiekwanhan Ehae” [Gospel and Culture, and Understanding of Woman’s Role in the Church] Mokhoewa Shinhak [Ministry and Theology] (May, 2004): 77-78. 37)Young-Jae Won, “Yugyomunhwa Yeonghyangeuroinhan Hankook Gyohoeui Sesokhwa,” [The Influence of Confucian Culture to the Secularization of Korean Protestantism] Gidokkyo Cheolhak [Protestant Philosophy] vol. 8 (June, 2009): 66. 38)Christian Institute for the Study of Justice and Development, Hankook Gyohoe Baeknyun Jonghap Yeonguseo [Analysis of Korean Protestantism Reviewing Its 100 Years] (Seoul: Christian Institute for the Study of Justice and Development, 1982), 161. 39)Jae-Kwang Gye, 94. 40)Jeong-Sook Lee, “Hankook Gaeshingyo Yeogyoyeokjaeui Inkwon,” [Human Right of Korean Protestant Woman Ministers] in Asia Yeosung Yeongu [Research on Asian Women] vol. 4 (2003): 145-149. According to this survey, in regard to education, one of the most important elements of church, female ministers spend only 5% at these among their allotted works, whereas male ministers spend most of their time doing this kind of core work, including preaching.

Woman Leadership in Korean Woman House Church

As we have seen in introduction of this paper, it is woman who plays a central role in woman house church, just as woman does in Shamanism. Several common aspects exist between woman house church and Shamanism. This section will explore woman leadership in woman house church (

Shamanism has survived as a popular religion, because Confucianism has not been able to satisfy the practical needs of people, particularly those of the lower-middle class, despite its dominance as the official religion under the

Similarities can be seen between Shamanism and woman house church (

As in Shamanism, the majority of woman house church leaders are women and adherents of both are of the lower classes. Today’s woman house church women are primarily lower-middle class women who have low-education careers. Unlike woman in patriarchal mainstream churches, the women in woman house church and mountain prayer centers play active roles. Most directors in mountain prayer centers are women. In addition, all of the leaders of the woman house churches are women, most of whom are lay people. In the meeting of the Daehan Christian Prayer Hill, a prayer center and birthplace of the organized woman house church, lay women led meetings including the sermon and Holy Spirit Dance, even though male pastors and elders were present.46) In local woman house churches, numerous lay women preach, preside over worship, and care for members, playing a role similar to that of male pastors in mainstream churches.

On the issue of woman leadership, the leader of organized woman house church points out the little room for woman to be ordained minister under the current situation of Korea. Though she had a dream to serve as God s daughter, it is hard for her to work as a leader in mainstream churches due to her low education career as well as her responsibility as a house keeper. The other reason derives from doing charismatic practice like healing prayer (

41Jong-Sung Choi , “Chosunsidae Yugyowa Musokeui Gwangye Yeongu” [A Study on the Relation of Confucianism and Shamanism in Yi-Dynasty], 236. 42Historically woman house church movement was originated from the mountain prayer center movement, which launched in the middle of 1960s and flourished in the 1970s and 1980s.. 43Myung-Hwan Tark, “Hankook Gidowon Undongeui Gongkwa,” [Evaluation of Korean Prayer Center Movement] Gidokyo Sasang [Christian Thought] vol. 18, no. 9 (1974), 53. 44Nam-Hyuk Chang, “Shamanism,” Sunkyowa shinhak [Mission and Theology] vol. 6 (2000): 159. 45Laurel Kendall, Shamans, Housewives, and Other Restless Spirits: Women in Korean Ritual Life (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1985), 27. 46My observation and explanation of the woman director of the DCPH, Myung-Hee Park.

Up to this point, we have examined different understandings of woman leadership in the two streams of Korean Protestantism, with a focus on the tension that exists between the male-centered Confucian culture and female-dominant Shamanistic culture. As in the Confucian social system, men have dominated the leadership within Protestant churches, with women excluded from the decision-making structure despite their numerical dominance. Under the influence of Confucian principles, Korean churches extended the segregation into its own religious environment, thus limiting the role of women in the church to the same subsidiary roles they played in their homes. Thus, until recently, women could not aspire to be pastor or elder.47)

Historically speaking, the period of development of the woman house church (

Because of its somewhat unorthodox characteristics, the movement produced tension within mainstream Protestant churches that, interestingly, share the same people as their members. As a voluntary church, woman house church created tension with the mainstream institutional church. Following in the tradition of female-based Shamanistic culture, the movement revealed a conflict with the male-centered Confucian mainstream church. However, woman house church leaders maintain that mainline church is to woman house church what public school is to after school institution. The purpose of woman house church is to return members to the mainline church after they are healed at the woman house church. In terms of the tension, one of the important things is to understand the woman house church movement. The understanding can lead us to have an expectation that the woman house church can provide challenge as well as hope for the mainstream churches particularly in terms of developing woman leadership and reforming churches.

47Woo-Jeong Lee, Hankook Gidokkyo Yeosung Baeknyuneuk Baljachi [Stories of Hundred years of Korean Women] (Seoul: Minjung Press,1985), 106.