One common element is that the major industrialized countries acted as main idea-promoters, aiming to establish the principles of interactions with ASEAN states. In relation to these idea-promoters, ASEAN has been positioned as a group of ‘distant’ states in two senses. First, they were distant from these idea-promoters in terms of the distribution of material capabilities. Most of them were placed on the lower layer of non-great powers, thus constituting no more than “a non-decisive increment to [idea promoters’] total array of political and military resources, regardless of whatever short-term, contingent weight […] it may have in certain circumstances” (Vital 1971, 9). Second, ASEAN leaders and these ideapromoters were distant in social terms with few shared social characteristics. They shared a common imminent threat of Communism during the Cold War, but such ideological affinity had not helped them to converge further in national values or political systems. Tensions between the two sides were particularly high due to incongruence in governance types. The major idea-promoters were all liberal democracies, upholding the protection of human rights, good governance, and the resolution of disputes by rules of law. In contrast, ASEAN states consisted of authoritarian republics, monarchies, communist one-party states, and weak democracies prone to repetitive military coups, frequent electoral fraud and official intimidation of the opposition. Leaders in these regimes frequently legitimized illiberal practices and values, resisting socialization into liberal Western culture. In the economic realm as well, their preference for authoritative allocation, cronyism, and patrimonial practices has always been a subject that causes tension with these liberal sponsors (Krasner 1985; Solingen 2001).

The ‘distant’ relations in terms of capability and identity have been a source of ASEAN state leaders’ persistent concerns over marginalization. As I discuss in another article, the marginalization can occur in two patterns (Bae forthcoming).6 First, they can be neglected by the dissimilar but dominant counterparts. In other words, ASEAN states are exposed to a high level of ‘attraction-deficit’. In relative terms, these weak dissimilar actors would be more concerned about attraction-deficit, compared to other weak actors with converging identities with super-ordinates or those who have built reliable institutional ties with them. For example, they are more concerned about the future withdrawal of a benign superpower than countries that have strong alliance and stable institutional ties with the superpower (e.g. U.S.-South Korea). Also, their concern would be more likely than that of leaders in powerful countries, which are courted by a number of small nations and political groups because of their affluent capital, technology, and resources. For example, major powers such as China and the United States would suffer little from fear that they will be neglected or sidelined on the major international affairs. Their size and material power in itself naturally draws small and middle powers which would want access to their resources when in need. That is, coping with the deficit would likely become a substantial goal for ASEAN states. Second, ASEAN states suffer from concerns that these major powers interfere in their internal affairs. Dominant powers are capable of imposing their preferred values or policies on weaker counterparts, particularly when the weak partners’ strategic values diminish. Moreover, the weak states with many dissimilar local practices with those of dominant ones could be more likely exposed to pressure for internal changes, compared to other weak ones with converging identities with the dominant powers. Therefore, ASEAN members could have a high level of concerns over possible interference from these idea- promoters of the West. In other words, ‘autonomy-deficit’ becomes another major source of their concerns.

1There are many studies which highlight the roles of non-state actors. For example, see Davies (2013), Hernandez (2006), and Kraft (2006). 2For the list of UN resolutions on related topic, see Phan (2008, 2). 3“Development Has for Long Been a Catchphrase for Inter-ASEAN Relations.” Jakarta Post (May 17, 1993). 4For a detailed discussion about the process, see Vitit (1999). 5Chalida, Director of People’s Empowerment Movement, interview with author, Bangkok, May 24, 2012. 6The discussion of this following paragraph cites the section entitled “neither left-out nor pushed-over: dual paths of marginalization” of my other article (Bae forthcoming).

ASEAN’S DILEMMA OF ATTRACTION-AUTONOMY DEFICITS AT THE REGIONAL LEVEL

The main claim of this study is that the dual-deficits, which stem from the relational positions of ASEAN leaders vis-à-vis idea promoters, have put a consistent constraint on the leaders’ choices and the ways that they adopted the ideas. ASEAN’s high level of concerns over dual-deficits does not mean that its leaders always stay alert to a possibility of marginalization. When their states or region become important sites for strategic purposes or resource security of some of these major powers, they can have more diplomatic room to maneuver or increase their leverage in relation to them. But ASEAN’s (real or perceived) marginalization becomes more likely when the major neighbors’ interests diverge from those of ASEAN states. Particularly, this can occur quite often because the pattern of interests changes frequently, as opposed to power or identity relations which tend to change more slowly (Snyder 1997). The ‘distant’ actor would seek to address such structural concerns by increasing their internal capabilities. However, it usually takes a long time. Becoming ‘us’ to the more powerful side would also be a good way to reduce the level of these concerns, but some leaders would just want to keep their national identities and not to abandon their differences. Also, even if they choose to become socialized with the bigger partners through more committed interactions, mutual credibility cannot be earned in a short time. Therefore, the weak dissimilar group needs additional short-term measures, other than ones for economic development and trust building to tackle these concerns over marginalization which can be triggered frequently.

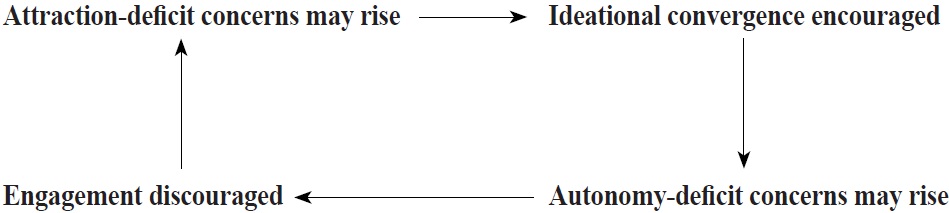

Ideational convergence to the idea-promoters, I argue, can be one of these short-term measures that these ASEAN leaders can take to cope with these dual-concerns, which arise in their distant relations to the major powers. It is because such ideational bonding is expected to draw the idea-promoters’ attention to the region, thus lowering the attraction-deficit concerns. However, if actors should cope with both attraction and autonomy deficits as in the case of ASEAN, it becomes difficult because of the inversely-related nature of the dual-deficits. For example, at a time when concerns over attraction-deficit rise substantially, ASEAN members would be willing to receive unfamiliar ideas that the promoters support and to change their local normative settings with an aim of a less tense relationship with them. However, in the asymmetric relations with these promoters, a straightforward pledge of ideational convergence may allow the promoters’ increasing pressure on the recipients for giving up their ‘otherness’ to an undesirable extent. Such a possibility could lead their concerns over autonomy-deficit to rise. The receivers then would prefer to buffer their autonomy by distancing themselves from active participation in normative regimes created by these promoters or by establishing alternative options that allow them to exit from the promoters’ influence. But excessively divergent moves or self-isolation can make the relations with the sponsors more distant, thus allowing them to leave or disregard the region even at a time when the weaker side asks for their re-engagement.

Overall, actors who suffer from dual-deficits, such as ASEAN, tend to face a dilemma where disproportionate emphasis on one side of concerns would aggravate concerns about the other deficit. This brings what I call ‘dilemma of dual-deficits’ (or dilemma of attraction-autonomy deficits) into their ideational or institutional changes.7

Due to the dilemma, the balance of the dual concerns should remain as a desirable goal that Southeast Asian elites at the ASEAN level would pursue. The dilemma expects that rising concerns over attraction-deficits vis-à-vis major powers would likely make ASEAN elites more willing to adopt new ideas that the major powers promote, such as human rights. However, as the elites want to prevent a new ideational commitment from raising the risk of autonomy-deficits, they would adopt the ideas only to the extent that the risk of autonomy-deficits does not offset the benefit of attracting the major powers through ideational bonding. If the adoption of such ideas is expected to aggravate autonomy-deficits, the leaders will not accept the ideas even though they are perceived to help attract the sponsors. Likewise, abating autonomy-deficit concerns would not suffice to motivate leaders to adopt foreign ideas. One may guess that the assurance of local autonomy will make the elites easily embrace the ideas because they are politically cheap. But, if the concept of dual-deficit dilemma is correct, ASEAN elites may not take locally-unfit ideas until a possibility of their being neglected by the idea-promoters pushes them to do so. In sum, due to the relational constraint vis-à-vis the major powers, ASEAN’s ideational changes would occur in a way that the leaders’ concerns over autonomy-deficits are tamed simultaneously with those of attraction-deficits. Propositions below summarize these expectations:

7The logic of abandonment-entrapment by scholars on alliance politics inspired the author to develop this concept of ‘dilemma of dual concerns’. See Snyder (1997).

How does one know whether the leaders’ collective concerns over dual-deficits would rise or fall? In this article I trace their actions as well as words expressed in public and private. For example, if specific anxieties are expressed frequently and evenly among many ASEAN elites in the same periods, it would confirm that ASEAN leaders’ concerns rise. Then, I examine whether and how the ideational changes occur in associations with the expressed concerns and see whether the results support the theory’s expectations. If, for example, the elites express concerns frequently that local input is not appreciated, spontaneous followership of ideas is not allowed, or a fixed set of prescriptions is provided by idea-promoters in an intrusive way, ASEAN elites are unlikely to embrace the ideas even at a time when attraction-deficits rise because the elites’ concerns over autonomy-deficit would be aggravated. To the contrary, if idea-promoters encourage ASEAN’s interpretation of ideas and remain accommodative, not confrontational, toward ASEAN’s leading role, or if the idea is accepted in a way that spontaneous engagement is assured, ideational changes would likely occur because the elites’ concerns over autonomy-deficit would not be aggravated. I rely on a combination of sources to trace ASEAN leaders’ concerns: public and private statements or interviews by ASEAN leaders and government officials; official communiqués of meetings of ASEAN heads and foreign ministers; opinions of local experts involved in ASEAN decision-making processes and opinions among critics in NGOs and academia. Admittedly, as one cannot identify actual perceptions and concerns without scanning human subjects’ brains, this study is mostly based on “expressed” concerns in public settings. In this sense, data collection is limited in identifying actual perceptions or concerns. However, identifying the expressed concerns has an advantage in understanding what this study aims to know. This study focuses on the collective concerns among ASEAN elites, not their individual ones. Of course, the individual perceptions among elites even within the same government are subjective and could differ. But the government elites usually stick to their government’s positions when speaking in public settings. Thus, it could be said that the expressed perceptions are collective, or inter-subjective, ones, which are commonly shared as the representative positions of their governments. Besides, this study tries to provide explanations about key events and backgrounds of the statements so that readers can better understand the contexts of the words or actions and to show that there was increasingly common expression of concerns across state leaders at a given time, which prompted leaders to take a collective action.

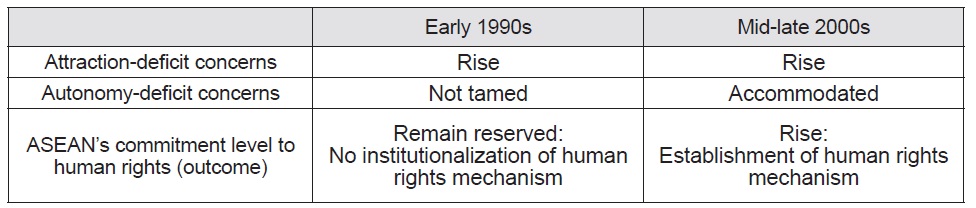

The following sections show that the theory of ‘attraction-autonomy dilemma’ explains ASEAN’s major responses to the diffusion of human rights. This study examines human rights norms as a useful area of empirical research for two reasons. First, while ASEAN’s human rights institutionalization has received much attention from academics as well as practitioners, the major existing theories were insufficient to understand the historical dynamics. In particular, they hardly explain variance in ASEAN’s response to human rights across time. In this regard, secondly, this study aims to introduce a new theoretical tool to better explain the variance. Its main purpose is to contribute to theory building, not theory testing. More studies for theory testing are required, but they are not a major intent of this study. Rather, this study takes human rights as a critical issue area and shows a detailed picture of whether and how the theory works. First, they trace the story of the early 1990s, explaining why ASEAN elites’ response remained reserved then. Next, they discuss why the elites increased their level of commitment to human rights in the late 2000s.

INSTITUTIONALIZING HUMAN RIGHTS IN ASEAN

>

CRITICAL RESERVATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS: THE STORY OF 1993

Human Rights Rose Globally When ASEAN Elites’ Concerns about Its Decreasing Leverage Increased

The end of the Cold War was followed by the increasing concerns of ASEAN elites over decreasing sponsorship. The downfall of the Communist bloc, policy shifts at the elite level, and the critical mood of the American public and Congress against the existing burden-sharing structure led ASEAN elites to worry about the eventual disengagement of the United States from the region. In a speech at the Indonesia Forum in 1990, Lee Hsien Loong, then Foreign Minister for Trade and Industry of Singapore, showed apprehension about the marginalization: “ASEAN may no longer weigh as heavily in the calculations of these major players. With the end of the Cold War, they will now feel less need to woo small countries and regional grouping” (Lee 1990). Even some Malaysian foreign policy elites, who had been vocal proponents for non-alignment and self-reliance, also expressed their concerns about the perceived U.S. disengagement. During the Cold War, they could play the Soviet or Communist card to gain what they wanted in relations with the United States and Western European countries. These major powers had taken a soft approach to Asia and other developing nations, emphasizing its political neutrality to the South. They had remained silent against human rights activists’ complaints over human rights abuses in many Asian countries including Indonesia, Malaysia, China and Sri Lanka, and kept providing these governments with military and economic support.8 However, the collapse of the Soviet Union reduced incentives to tolerate the human rights abuses of authoritarian governments in an effort to maintain anti-Communist alliance.9 As the Cold War came to an end, these elites were concerned about the consequences of the loss of leverage. Malaysian prime minister Mahathir described his fear of marginalization that increased with the end of Cold War bipolarity as follows: “Weak nations with no leverage can only become weaker…Without the option to defect to the other side, we can expect less wooing but more threats” (cited in Foot 1996, 20). Noordin Sopiee, director of Malaysia’s influential think-tank, Institute of Strategic and International Studies (ISIS) in Malaysia, also commented that most Third World countries would be more peripheralized because superpowers would tolerate the indulgence of the lesser powers less when bipolar rivalry was over (cited in Foot 1996).

Human Rights Grew Stronger Globally

Since the end of the Cold War, the United States and advanced countries in Europe became more involved in building a global human rights regime and new norms such as responsibility to protect and human security emerged. Humanitarian interventionism became more prominent with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO’s) military actions in Somalia and former Yugoslavia. The newly elected U.S. president Bill Clinton affirmed his willingness to spread American values and to undertake domestic institutional reforms for this task. For example, the State Department created a new position of Undersecretary of State for Global Affairs in order to handle democracy, human rights, labor and environmental issues. The White House’s National Security Council created three new positions for democratization and human rights.10 The Ministry of Defense also implemented internal reforms, replacing the existing offices of international affairs with a few posts handling new issues of human rights violations and democracy in the post-Cold War period. The administration also created a new post of Assistant Secretary of Defense for Democracy and Human Rights and appointed Morton Halperin who had led projects on possible U.S. actions for legitimate self-determination movements.11

Europe also took a similar turn in foreign policy. With the end of the Cold War, European Community (EC) foreign ministers declared that they would impose tough political and economic conditions on their financial assistance programs for Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. At the same time, Britain, Denmark, and the Netherlands pushed the EC to apply similar criteria on other continents. From the beginning of the 1990s, the EC started to introduce tougher guidelines on its foreign aid program for Asia, declaring that the new policy reflected “a legitimate concern under international law, essential for the creation of a sound political climate fostering peace, security and cooperation.” Officials said that such political criteria would apply to all aid disbursed by the Community and its member states—estimated approximately at US$28 billion annually.12 The European Community also wanted to include a human-rights clause in its cooperation agreements with ASEAN that would allow it to suspend aid to human rights violating countries.13 Besides, along with these post-Cold War changes, many groups in Southeast Asian civil societies tried to engage more in the West’s increasing effort to build a human rights regime. The voices of intergovernmental and transnational pro-human rights coalitions for the institutionalization of regional and domestic human rights mechanisms in East Asia have increased.

With Rising Concerns over Autonomy-deficits, ASEAN Elites Called for the Pluralistic Implementation of Human Rights

As human rights norms became more prominent in the international arena, ASEAN elites quickly linked human rights with the issue of sovereignty and power differentials in the international system.14 Thai prime minister Chuan Leekpai, the first democratic leader that came to power in 1992, claimed that Thailand did not share an individualistic view on human rights; the interest of society, state and nation was also a crucial condition that could be prioritized over individuals.15 Malaysia’s Ahmed Badawi warned that “attempts to impose the standard of one side on the other… tread upon the sovereignty of nations.”16 This was also a sensitive issue for Indonesian elites because they worried that Indonesia, a country consisting of diverse ethnic and religious groups, might run the risk of civil wars if they adopt the norm which focuses on individuals’ rights over a state’s right to impose order.17 Indonesia’s Ali Alatas’ comments were explicit: “in a world where domination of the strong over the weak and interference between states are still a painful reality, no country or group of countries should arrogate unto itself the role of judge, jury and executioner over other countries” (Alatas 1993). He believed that “If you [the West] want to evaluate us, do it on the totality, not just civil and political rights. We are all for democratization, not just within countries but also between countries— democratization of international relations.”18 As a response to the global demand for conformity, Mahathir went one step further, suggesting communitarian and collective “Asian Values” as an alternative moral standard of his region. Singapore agreed, invoking the Confucian idea of “community over individual” (Mahbubani 1992, 15). Furthermore, other ASEAN leaders did not directly challenge their discourse or provided tacit support to it (Nesadurai 2009).

Washington Denied ASEAN Elites’ Inputs

However, such a pluralistic input received a serious backlash from human rights advocates including state sponsors of the West. Particularly, Washington kept pushing for international scrutiny for countries with poor human rights records. U.S. Chief Delegate Kenneth Blackwell complained that “no more than a dozen countries… are hell-bent on derailing the [Vienna] conference,” among which Southeast Asian countries were particularly noted. Some U.S. officials placed Indonesia and Singapore in the worst group and ranked Malaysia and Burma as unhelpful countries.19 U.S. Secretary of State Warren Christopher said that Washington “will never join those who would undermine the Universal Declaration”1and “those who desecrate these rights must know that they will be ostracized. They will face sanctions. They will be brought before tribunals of international justice. They will not gain access to assistance or investment.”20

ASEAN Remained Reserved about the Global Human Rights Regime

Admittedly, there was also a pro-human rights member among ASEAN’s (then) six countries. The Philippine government had remained exceptionally supportive of promoting a human rights regime in the region. Roberto Romulo, Foreign Affairs Secretary of the Philippines, was one of a few elites in ASEAN who called for an end to excuses for “the separate advocacy of the various sets of human rights.”21

However, as autonomy-deficit concerns grew among most member states, the pro-human rights voice had to be compromised at the ASEAN level. The idea of joining in the global human rights regime disturbed most Southeast Asian leaders who suffered from substantial levels of autonomy-deficit. Malaysian deputy prime minister Abdul Ghafar Baba also stuck to Malaysia’s original position, “no ready-made model can be prescribed and no group should take upon themselves the role of judge and jury in the matter of common concern to the international community as a whole.”22 Prasong Soonsiri, Foreign Minister of Thailand, also added, “[the international community’s concerns about human rights] should in no way be translated into interference in domestic affairs or serve as a pretext for encroachment on the national sovereignty of a state.”23 Ali Alatas claimed that Indonesia could do a lot with Western partners regarding human rights issues but it did not want them to be “a condition” for cooperation.24

Overall, ASEAN refused to institutionalize liberal human rights in the region. As for a response to the Vienna Conference’s call for the establishment of regional human rights mechanism, ASEAN foreign ministers declared collectively that they would “consider” building the appropriate one, but reaffirmed the priority of each state’s decision to establish its national commission (ASEAN 1993). This pledge was recalled in the subsequent annual ASEAN Foreign Ministers Meeting (AMM) communiqués, but it was not tabled as the official level agenda for another ten years.

8“Under Western Eyes.” Far Eastern Economic Review (March 14, 1991), 20. 9“Vienna Showdown.” Far Eastern Economic ReviewFar Eastern Economic Review (June 17, 1993), 17. 10“Do unto Others.” Far Eastern Economic Review (July 1, 1993), 18. 11“Telltale Titles.” Far Eastern Economic Review (February 1, 1993), 15. 12Quoted in “Under Western Eyes.” Far Eastern Economic Review (March 14, 1991), 20. 13“Values for Money.” Far Eastern Economic Review (June 20, 1991), 9–10. 14“Cultural Divide.” Far Eastern Economic Review (June 17, 1993), 20; “Standing Firm.” Far Eastern Economic Review (April 15, 1993), 22. 15“Standing Firm.” Far Eastern Economic Review (April 15, 1993), 22. 16Quoted in Strait Times (July 23, 1991). 17“Indonesia Runs the Risk of a Civil War.” Jakarta Post (April 2, 1993). 18A. Alatas. Interview with Far Eastern Economic Review (July 11, 1991), 12. 19Cited in “Vienna Showdown.” Far Eastern Economic Review (June 17, 1993), 17. 20Cited in “No Country Should Arrogate unto Itself the Role of Judge.” Jakarta Post (June 16, 1993). 21“Romulo Criticized What He Called the Use of the Issue as an Ideological Weapon.” Jakarta Post (June 17, 1993). 22Cited in “ASEAN was Formulating a Common Position ahead of the Global Conference.” Jakarta Post (April 16, 1993). 23“No Country Should Arrogate unto Itself the Role of Judge.” Jakarta Post (June 16, 1993). 24A. Alatas. Interview with Far Eastern Economic Review (July 11, 1991), 12.

INSTITUTIONALIZED ACCEPTANCE OF HUMAN RIGHTS: THE STORY OF 2003

>

Western Powers’ Leniency to Southeast Asia Decreased

In the early 2000s, ASEAN and its member states again started to face an increasing “criticism of irrelevance” vis-à-vis the West again. A common perception among its elites emerged that East Asia’s economic center of gravity had shifted markedly toward Northeast Asia and away from Southeast Asia since the 1997 financial crisis because of differences in the speed of recovery between the two regions.25 China’s rise was a particular concern because China became the largest single recipient of foreign direct investment (FDI) after 1997 while ASEAN countries were facing a downturn. China alone had drawn 60% of the total foreign direct investment flown to East Asia in 2000 (Ravenhill 2006).26 Meanwhile, ASEAN’s share of FDI inflows to China, Hong Kong, and ASEAN countries decreased to 20% from 2000 onward while it constituted 40% of the inflows during 1992–1997 (Ravenhill 2006).

Furthermore, news from Myanmar on its Black Friday incident further provoked other ASEAN members (Haacke 2005). The incident was particularly disturbing because it happened when the international community started to express hope that Myanmar’s ‘new dawn’ was coming as Aung San Suu Kyi had been released unconditionally in May 2002. However, as she received great acclaim from inside as well as outside Myanmar, the anxious junta tried to suppress her rise again, physically attacking her supporters one night in May 2003, leaving dozens dead. Right after the incident, the military junta announced her detention in a Yangon prison (Kuhonta 2006).

International pressure surged. Not only did Western donors threaten to withdraw aid from Myanmar but they also initiated new sanctions on Myanmar. Since Myanmar had been a part of ASEAN since 1997, more international audiences turned their attentions toward ASEAN and called on its members to pressure the junta to release Aung San Suu Kyi and start the national conciliation process. Washington refused to participate in any Myanmar-chaired ASEAN meetings and threatened to cut funds for regional development if Myanmar took over as the chair of ASEAN in 2006. Former President of the U.S.-ASEAN Business Council Ernst Bower warned, “[…] ASEAN’s global profile could be severely damaged by Myanmar’s chairing of the grouping. Such damage would come at a time when it can be least afforded.”27 In 2005, U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice skipped the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) meetings for the first time to further pressure ASEAN. Similarly, the European Union (EU) took a hard line, threatening to hold the Asia-Europe Meeting only if the junta did not participate in them or made political concessions before participation.

>

ASEAN Elites’ Concerns over Attraction-deficits Increased

ASEAN leaders read these as a signal that the Western donors would keep away from the region if it was dragged along by Myanmar. The credibility issue was consistently raised by ASEAN leaders, who were concerned that Myanmar prevented ASEAN from focusing on attracting the outside world. Philippine Foreign Ministry of the Philippines Blas Ople also opposed the principle of absolute non-interference in case one country’s domestic affairs negatively had affected its neighbors.28 Surprisingly, Mahathir, who had been the most vociferous opponent to external interference, went further, suggesting that Myanmar should be expelled from ASEAN in case ASEAN was held hostage by Myanmar’s leadership: “We are not criticizing Myanmar for doing what is not related to us, but what they have done has affected us, our credibility.”29 Lee Hsien Loong also noted that the incident in Myanmar made ASEAN elites realize “in an interdependent world, developments in one ASEAN country could impact on ASEAN as a whole.”30 The executive director of the Center for Stategic and International Studies (CSIS), Hadi Soesastro, noted, “ASEAN’s future relevance to its members and to the region suddenly becomes a relevant question in many quarters…ASEAN, some have argued, cannot maintain its relevance if it continues to be inhibited by the principle of non-intervention that it has held sacrosanct” (Soesastro 1999, 159). A foreign affairs advisor to Indonesian president Habibie, Dewi Fortuna Anwar, also criticized ASEAN members of having grown used to sweeping problems under the rug, calling for changes in the ASEAN way of doing business.31 According to ASEAN Secretary General Ong Keng Yong, ASEAN needed to reform and consolidate itself in order to reassure external sponsors’ continued commitments (Ong 2009).

Overall, ASEAN elites felt that they were withering into insignificance vis-à-vis major Western countries.32 They believed that to stay as benign spectators would “take the shine off” the region’s profile eventually and help push China to the center of Asia’s geopolitics.33 With increasing international criticism and pressure on the Burmese junta, ASEAN leaders found it necessary to play a meaningful role in order not to be bypassed with regard to the critical issue of its own region.

>

ASEAN Elites Started to Discuss the Institutionalization of Human Rights

In order to address their weakening position in relations to their major external allies, ASEAN members collectively initiated ambitious projects. ASEAN’s construction of a regional human rights body began in this context. In 2003, Indonesia drafted a plan of action for the inclusion of democratic values and human rights as the agenda for ASEAN Security Community pillar.34 Based on the 2004 Vientiane Action Program, the process sped up when leaders in the 2005 Summit agreed to confer ASEAN a legal personality by drafting the ASEAN Charter (ASEAN 2005). According to Foreign Minister of Indonesia, Hassan Wirayuda, “We can’t become the ASEAN community that we have envisioned ourselves to be until and unless the promotion and protection of human rights is pervasive in our region.”35

However, the creation of a human rights body was apparently not an easy process due to the dilemma of inversely-related deficits. The institutionalization of their engagement in the human rights regime could receive international acclaim and prevent angry sponsors from taking leave of the region. But it might also widen a space where the promoters of human rights could more legitimately meddle in case ASEAN states’ internal businesses negatively affected human rights issues.

According to a memoir of Tommy Koh, a Singaporean representative to the high-level task force (HLTF) on drafting the ASEAN Charter, the positions of HLTF members were divided into three camps: opposition from Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam; Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore in the middle; Indonesia in favor; and the Philippines reserved in the first place but more in favor later (Koh, Manalo and Woon 2009). According to an ASEAN Secretariat official, Vietnam, Laos and Myanmar threatened twice to walk out of the entire Charter-making process when it was suggested that the Charter include a clause on regional human rights mechanism (Jones 2010). According to Indonesian sources, Indonesia was the only country that maintained its stance in favor of a human rights body that could provide minimum explicit protection of human rights victims of the region.36

>

ASEAN Accommodated Dual Concerns, Pursuing an Autonomous Adoption of Human Rights

In spite of rising concerns over autonomy-deficits among the leaders, ASEAN adopted human rights norms at a meeting on July 2007, establishing an ASEAN human rights body, named the ASEAN Inter-governmental Commission on Human Rights (AICHR), “in conformity with the purposes and principles of the ASEAN Charter relating to the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms” (ASEAN Charter, Article 14). This is notable because, as one former staff of the ASEAN Secretariat noted, the establishment of a regional human rights body was brought up and agreed by foreign ministers themselves, not from the Eminent Persons’ Group or other advisory members.37

However, ASEAN’s moves for the implementation of the agreement reflected its dilemma of attraction-autonomy deficits. In a series of negotiations after the foreign ministers’ pledge, ASEAN elites agreed on the specific terms of human rights cooperation at the ASEAN level, which could accommodate their concerns over both attraction and autonomy deficits.

First, the proposals for introducing voting systems to replace consensus-based decision making rules were dropped. The maintenance of consensus-based rule implied that the members could be reassured that they ran little risk of being trapped in the obligations to which they were not ready to commit (Katanyuu 2006). According to Wiwiek Setyawati, Director of Human Rights Affairs at the Indonesian foreign ministry, “the underlining message from the ministers was that the panel [who would draft the Terms of Reference for the establishment of the human rights commission] has to be realistic by looking at the comfort level of the ASEAN members and at what stage of democracy they are in.”38

Second, they agreed to start talking about human rights with common themes that all members had shared. For example, all members joined the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child; all except Brunei were parties to the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women; six of them joined the International Labor Organization’s Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention (Severino 2006). Such common stances made a regional consensus easy on these issue areas, leading ASEAN leaders to sign the ASEAN Declaration on the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Migrant Workers and to establish the Commission on the Promotion and Protection of the Rights of Women and Children, aside from AICHR.

Third, they rejected any regional mechanism for enforcement. Indonesia had eagerly proposed that AICHR have monitoring, education, standard setting, investigation and advisory services mechanisms.39 However, Indonesia remained the only member to support an enforcement mechanism for human rights protection as an integral part of AICHR. Other countries, including democratizing ones, remained silent or ambiguous about their positions.40 According to the Vietnamese representative to the HLTF, a common understanding among officials was that ASEAN needs to make sure that “human rights should not be left as an excuse for outsiders to intervene into the ASEAN’s own affairs” (Nguyen 2009, 103). Thai foreign minister Kasit Piromya added, “We deal with it [human rights violations] through good offices first and then arbitration. We do it in a civilized way—working together from inside out and not waiting for outsiders to punish us.”41 In order to achieve the goal, a mechanism to sanction non-compliance was a risky option which would provide external sponsoring countries, the United Nations and pro-liberal civil societies with a wider and more legitimate venue for legal appeals and pressures.

Overall, the way that human rights mechanism was institutionalized within ASEAN is compatible with the expectations of the dual-deficit dilemma argument. With the slow recovery of the region from the 1997 financial crisis and the rise of alternative investment destinations and markets such as China and India, Southeast Asian elites started to worry that ASEAN as well as their own countries might lose their relevancy in the global scene. Moreover, the news about the political oppression of Myanmar’s military regime provoked global criticism not only against the regime but also against ASEAN for not doing anything. This further heightened ASEAN elites’ concerns over their attraction-deficits. In order to mitigate their fear of becoming ‘irrelevant,’ they initiated many ambitious projects. One proposal was to institutionalize human rights within ASEAN, which had been resisted for years. However, illiberal practices were still prevalent in most member countries, especially new members; the idea of having a human rights body within ASEAN provoked many elites’ concerns about unwanted foreign influence. However, maintaining the status-quo could have further increased their concerns over attraction-deficits, by creating the impression that Southeast Asia was not ready to join in the worldwide trend toward liberalism and human rights, and would thus be isolated without a willingness and capacity to address critical regional issues such as Myanmar’s political oppression. In order to cope with the dilemma of attraction-autonomy deficits, ASEAN elites accommodated both concerns. They adopted human rights as a fundamental principle that constitutes the ASEAN Charter and attracted positive attention from the West. However, their decision was limited to bringing the domestic human rights issue around the ASEAN table, not fully endorsing the mechanism of enforcing what they would discuss at the ASEAN level.

25“Asians Take Steps to Unify Southeast and Northeast Blocs.” International Herald Tribune (November 25, 2000). 26Also, “Asians Take Steps to Unify Southeast and Northeast Blocs.” International Herald Tribune (November 25, 2000). 27Cited in Channel News Asia (July 22, 2005). 28Cited in Agence France Press (June 18, 2003). 29Quoted in “ASEAN and Aung San Suu Kyi.” Jakarta Post (July 24, 2003). 30“PM Holds Talks with Myanmar Leaders.” Straits Times (March 31, 2005). 31Cited in “ASEAN Struggles to Change its Reputation as Weak, Helpless and Divided.” International Herald Tribune (April 22, 1999). 32“ASEAN at a Crossroad.” Jakarta Post (August 8, 2005). 33“Yangon Chairmanship up in the Air at ASEAN Huddle.” Straits Times (July 25, 2005). 34Far Eastern Economic Review (July 15, 2004). 35“ASEAN Human Rights.” Jakarta Post (December 21, 2006). 36“Human Rights: A Struggle Going Nowhere?” Jakarta Post (July 24, 2009). 37A former ASEAN Secretariat’s official, confidential interview with author, Singapore, March 22, 2012. 38Cited in “ASEAN Rights Body Risks Losing Power.” Jakarta Post (July 22, 2008). 39“ASEAN Rights Body Risks Losing Power.” Jakarta Post (July 22, 2008). 40A senior Indonesian scholar, interview with author, Kuala Lumpur, May 30, 2012. 41“ASEAN Compromising Even on Human Rights.” Bangkok Post (July 22, 2009).

This article does not attempt to argue that the relational concerns over dual- deficit dilemma “determine” ASEAN’s decisions for its liberal turn. Rather, it is claimed that ASEAN’s relational position vis-à-vis the major powers consistently affected the way ASEAN adopted human rights and the timing in which they were adopted.

Findings in the previous sections support this argument that ASEAN’s dilemma of dual-deficits would explain its commitment to human rights. ASEAN elites became more willing to adopt this foreign idea since the mid-2000s. As major sponsors’ leniency decreased, they were motivated to increase their commitment level to human rights so as to prevent the idea-promoters from turning their backs against them or avoid being irrelevant to the idea-promoters (Proposition 1). Converging attitudes or behaviors could bring these ‘recalcitrant others’ more opportunities to bond with the potential sponsors, thus ameliorate the level of their concern about being sidelined. ASEAN’s stated goals to manage ‘crucial global issues’ and demonstrate to the outside world its capacity as an effective organization were indications of the leaders’ willingness to act, drawing attention from their potential sponsors again (ASEAN 2007). However, the event of 1993 shows that an increase in concerns about attraction-deficits was not sufficient to make them take the idea (Proposition 2). Human rights failed to be institutionalized at the ASEAN level in 1993 because ASEAN elites’ concerns about autonomy-deficits that rose simultaneously were not accommodated due to the major powers’ unilateral demands for convergence. On the other hand, the level of commitment to human rights grew substantially in the late 2000s when not only the idea promoters’ leniency fell but ASEAN’s ownership to implementation of human rights was also institutionally ensured. In other words, what they wanted was the balanced management of dual concerns so that they neither remained left out nor pushed over in their relations with the concerned idea promoters.

This article provides some theoretical and policy implications about Southeast Asia’s ideational congruence. First, the relationship between idea-receivers and idea-promoters has a significant impact on the receptive behaviors. When faced with the external actors’ promotion of new ideas, the primary concern of the ideareceiving side was not just the contents of the ideas per se, but the relations with the idea-promoters that the ideational changes would affect. Several previous studies already pointed out the issue of ‘who’ carries the ideas to ‘whom’, such as the importance of idea entrepreneurship (Finnemore and Sikkink 1998; Garcia 2006; Nadelmann 1990); idea-carriers’ features such as their experiences, capacity or strategy (Keck and Sikkink 1998; Ba 2009); and idea-receivers’ characters (Levitsky and Way 2006). This study adds to the literature, asserting that the relational structure between idea-promoting and idea-receiving sides matters in the process of idea delivery and reception.

Related to the point above, this study provides some lessons on ‘how’ to deliver ideas. Even though ASEAN takes seriously the major powers’ demand for ideational congruence, it would be counterproductive for idea-promoters to take coercive measures to reform ASEAN to the extent that ASEAN’s concerns on autonomy-deficits override those on attraction-deficits.

Furthermore, this study can provide some lessons about ‘when’ to deliver ideas. Numerous studies in norm diffusion have focused on the effective strategies that the norm-diffusing side should take to convert the receiving-side. However, the impact of the timing of diffusion has not been largely explored. The theory presented here implies that the issue of ‘when’ to deliver ideas and call for receivers’ commitment also becomes important in forming strategies for successful diffusion. Admittedly, the idea of the establishment of regional human rights body did not emerge out of nowhere with the elites’ stated concerns. The elites’ decision to establish a regional mechanism was made on the foundation of the accumulated efforts by diverse non-governmental actors. Civil society in Asia had come together since the early 1980s to work for the establishment of a regional human rights mechanism. Following a series of UN resolutions for regional human rights mechanisms in the 1970s, several legal personalities established Regional Council on Human Rights in Asia and drafted ASEAN’s declaration on the basic duties of ASEAN peoples and governments in 1983.42 At the end of the Cold War, ASEAN-ISIS started the Colloquium on Human Rights and built a regional coalition dubbed the Regional Working Group for an ASEAN Human Rights Mechanism, in order to advocate for a human rights mechanism at the ASEAN level and kept trying to engage in multiple programs for an official regional mechanism.43

However, these accumulated processes appear insufficient to understand when or how such efforts had come to fruition. Rather, considering that such effort has been constant since the early 1980s but ASEAN has been silent constantly until major changes occurred outside of the region, this article notes that it would be the elites’ rising concern over increasing irrelevance in the early 2000s that triggered ASEAN leaders to pick up on this ‘let’s talk about human rights’ card on the table. Also, this article disagrees with the idea that a deeper engagement and persuasion from the West would work for ASEAN’s normative congruence with the West. Rather, it suggests a different mechanism, noting that when there is an increasing detachment of ASEAN’s existing sponsors from the region, instead of its increasing engagement, or the threat of such detachment, ASEAN leaders would be more willing to listen to new ideas promoted by major powers, which could potentially provide sponsorship and thus abate their attraction-deficit concerns.

42“Development Has for Long Been a Catchphrase for Inter-ASEAN Relations.” Jakarta Post (May 17, 1993). 43Chalida, Director of People’s Empowerment Movement, interview with author, Bangkok, May 24, 2012.