There are two archives in Korea where one can find conversion narratives authored by political prisoners during the colonial period. The first is the Kyŏngsŏng District Court (Prosecution Division) Document File at the National Institute of Korean History (NIKH).1 The other is the Parole-Related Documents on Independence Activists2 at the National Archives of Korea. The research for this article is based on the prison documents found in the NIKH archive.3

Studies on

The article argues that “conversion novels” in Korea are analogous to the conversion narratives written in prison, in terms of their narrative structure and contents, and in terms of the state surveillance system under which they were both written. The article further argues that conversion novels in Korea cannot be read as a representation of a transparent authorial self but as a portrayal of how a normative and schizophrenic authorial self is formed under the disciplinary powers of the state.

1Conversion narratives written by political prisoners appear under a host of different headings in the NIKH archive. One that appears most frequently is kamsangnok (record of impressions), and in this article I use the term generally to refer to conversion narratives written by political prisoners during the colonial period. Other titles, as they appear in the NIKH archive, include sangsingsŏ (report), kongsulsŏ (affidavit), chinjŏngsŏ (petition), chŏnhyanggi (record of conversion), chŏnhyangsŏ (letter of conversion), chŏnhyang ch’wiŭisŏ (letter of intent to convert), chŏnhyang sŏngmyŏngsŏ (statement of conversion), sasang chŏnhyangnok (record of ideological conversion), yŏndu sogam (thoughts on the new year), kamsanggi (journal of impressions), chŏnhyangmun (essay on conversion), simgyŏng kobaek (confession on the state of mind), and simgyŏng kobaeksŏ (confession letter on the state of mind). 2See Kim Chŏnga, “Ilche kangchŏmgi tongnip undongga ‘Kach’urok kwan’gye sŏryu e taehan kŏmt’o” (Review of “parole documents” on independence cctivists from the Japanese colonial period) for a general introduction to and a review of the current status of this archive. 3I thank Professor Hong Jong-wook for informing me of the existence of this archive and for sharing with me the fruits of his labor. The size of the NIKH archive is massive, and the documents are not sorted. He searched for what appears to be a conversion essay, or a kamsangnok, from the annotated volumes of the massive archive; after identifying and photocopying each document from microfiche, he analyzed the documents further and turned them into usable data. For the conversion narratives discussed in this article, I selected entries from his list that are particularly representative of the “conversion grammar” I discuss later. This article is much indebted to Professor Hong’s work.

READING CONVERSION NOVELS IN KOREA

Unlike in Japan where there has been a tradition of accepting ideological conversion by Marxists and other leftists in Imperial Japan as neither good nor bad in and of itself,4 ideological conversion by literary writers—leftist and nationalists alike—in Korea was equated with the betrayal of the nation, a moral failure of the highest kind.

With this historical-academic legacy, scholarship on conversion in the field of Korean literature has long focused on differentiating “non-conversion,” “disguised conversion,” and “complete conversion.” The different levels of conversion were then translated directly into varying levels of anti-Japanese resistance or pro-Japanese cooperation.5

More recently, a number of attempts have been made to break away from this approach and to understand conversion—particularly those that occurred towards the end of colonial rule—from the broader context of the relationship between the formation of the subject and the state disciplinary apparatuses.6

They are both abstract in their approaches, in that they both assume that conversion novels were written in a transparent language that directly reflects the authorial self of the

The starting point for reading a conversion novel in this article is to understand conversion as a matter of legal procedure. The ultimate goal of the state in forcing a political prisoner to recant his/her belief is the rehabilitation of social normality, or the prisoner’s compliance to dominant social norms. The state authorities accomplished this by forcing a political prisoner to submit to the legal system, the minimum process for making a recalcitrant subject conform to ruling social norms. Thus, as soon as a political suspect was arrested, a host of legal proceedings awaited him, during each step of which various state apparatuses were mobilized to induce his subordination to the legal system. It was as a part of this process that political prisoners were forced to enunciate their conversion, in both speaking and writing, as if the conversion were already a fact.

A

The conversion narratives, taking the form of a confession, were addressed to a police officer, prosecutor, judge, or prison chief specifically in charge of the prisoner or his legal case. The narratives assured the respective reader that the author would abide by dominant social norms in the future. In terms of how and why they came to “correct” their deviation from the norms, the key words used in their alibi were, for example, “livelihood” and “family.”

Some conversion narratives also discuss and embrace the Japanese imperialist notions of command economy and racial harmony. They are indeed efforts to comply with the dominant social norms. In other words, the state defines Marxism, for example, as an abnormality, and demands that such an aberration be corrected. The

The motives and rationale for conversion that appear in the prison conversion narratives reappear in literary works by conversion writers outside of prison. As

While conversion novels and the prison narratives both employed the same, officially-sanctioned conversion motives and rationale, the former, i.e., the novels, also employed narrative strategies that tried to exonerate the writer; in other words, while a

More specifically, the article will first review the institutions of conversion, delineate “conversion grammar”8 from the archival documents, and finally analyze a conversion novel by Kim Namch’ŏn, whose work seemingly abides by the rules of conversion grammar while at the same time disrupting and breaking them. The purpose of this exercise is to re-evaluate the conversion novels left behind by a whole group of Korean writers from the colonial era. They comprise an important literary heritage left behind by writers who disrupted the censorship apparatuses of the time and who lived and worked fiercely as they agonized deeply about ideas and ethics.

4Tsurumi, Chŏnhyang: SSŭrumi Shunsuke ŭi chŏnsigi Ilbon chŏngsinsa kangŭi 1931–1945 (Conversion: lectures by Tsurumi Shunsuke on the intellectual history of wartime Japan, 1931–1945), 222. 5See, for example, No, Han’guk munin ŭi chŏnhyang yŏn’gu (A study on the conversion of Korean literary writers); a passionate work by Im, Ch’inil munhak ron (Discourse on pro-Japanese literature); and Kim, Hyŏmnyŏk kwa chŏhang (Cooperation and resistance) a post-colonialist attempt to analyze colonial-era Korean literature in terms of collaboration with, and resistance against, colonial authorities. Despite their differences, the three works share a commonality in that they unconsciously equate pro-Japanese/anti-Japanese and collaboration/resistance with conversion/ non-conversion, respectively. 6Examples include Kim and Sin, Munhak sok ŭi passijŭm (Fascism within literature); Kim, Kungmin iranŭn noye (Slaves who are called the people); Cha, “Chusang kwa kwaing: Chung-Il chŏnjaenggi cheguk/singminji ŭi sasang yŏnswae wa tamnon chŏngch’ihak” (Abstraction and excess: Imperial/colonial ideological linkage during the era of the Sino-Japanese War and the politics of discourses); Jeong, Tongyangnon kwa singminji Chosŏn munhak (The discourse on the East and literature in colonial Korea). These are post-modernist and post-colonialist studies that do not equate the term “pro-Japan” with the loss of subject or voluntary cooperation with colonial authorities but read in it the formation of a disciplinary self under the disciplinary powers of the colonial state. 7Conversion novels are expected to be read as I-novels where the author, narrator, and character are assumed to be identical. Tomi Suzuki (1997) has said that a text, no matter what kind it is, becomes an I-novel if it expresses “directly” the author’s “self” in a unified voice, and if the text can be read as “transparent.” In the case of Korean conversion novels, despite the self-referential context of I-novels that the authors employ, one must break away from the fantasy that the literary text is a transparent language that reveals the author’s inner self; only then would the contemporary context of the colonial-era conversion novels be fully revealed. 8“Conversion grammar” is a term I use to refer to certain structural and narrative patterns commonly found in conversion narratives officially approved by colonial authorities. Such narratives, i.e., confession letters, appear, for example, in Sasang hwibo, or Shisō ihō (Ideology bulletin), an organ of the Office of the Governor-General of Korea. They characteristically contain the following narrative elements: 1) the formative process of ideological affiliation, or how the prisoner became a Marxist, for example; 2) self-reflections on the wrongs of the ideology; 3) self-awakening to family responsibility and family love; and 4) pledge of loyalty to the state (Imperial Japan) and commitment to gainful employment.

THE LEGAL PROCESS OF CONVERSION AND THE TECHNOLOGY OF CONFESSION

“Conversion” in colonial Korea is a phenomenon that must be understood primarily as a function of the laws of the time. However, discussions on the topic have generally overlooked this very obvious but important aspect and focused, instead, on explaining it as violence perpetrated by imperialism, thus making the very real process an abstract notion. In the following section I give a brief overview of the legal process of how an ideological conversion takes place.

A man is arrested on suspicion of being a socialist. A police officer is interrogating him at a police station. Here, “interrogation” is a euphemism for torture.9 The suspect succumbs to the torture and gives away information about his comrades and organization. This breaks his body and mind. However, the interrogation does not end here. He is forced to repeat what he has “confessed,” either in writing or speech, all the while still calculating what must remain revealed or concealed from the police.10

The case is now turned over to the prosecutor. The prosecutor demands that the accused repeat his confession all over again in writing.11 In the process of this repetition, many political prisoners actually adopted the strategy of accom-modating the demands of the colonial authorities by producing an appropriate text while nevertheless preserving their Marxist or socialist conviction and protecting their organization; there were also others who indeed changed their views. In any case, the accused must now write yet another letter to the prosecutor and narrate his case.

The accused is now ready for a trial. At this stage, the accused, now a defendant, must again submit a written letter of confession, this time to a judge. At court during the trial itself, the defendant may be asked to repeat his confession, his conversion narrative, as an oral statement. Common sense dictates that a defendant in such a trial would defend his position and argue for his innocence. However, a conversion that takes place in court in the end takes the form of a confession.

Once the trial is over and the defendant is found guilty, he is sent to prison. He is now a convicted prisoner. He is due for release upon completion of his sentence. However, once he completes one-third of his prison term, he is eligible for parole. Parole is determined on the basis of his prison-service record, including any “signs of reform.” Also crucial for the consideration of parole is the submission of yet another confession letter from the prisoner. The following diagram summarizes the legal process that a convicted socialist or Marxist would have most likely gone through during the colonial period:

Conversion is a phenomenon that occurs at some point in the progression of the legal process summarized above. One must notice that a conversion during this legal process takes place in the form of a confession in which the confessor reveals his inner-self to the state and to society at large. In order to explain his motive for conversion effectively, the prisoner had to present a structuralized view of his past life and adopt a proper narrative style to convince the authorities that his conversion is authentic. The narrative had to include a pledge, or a plan, for how he would live his post-conversion life. The format and the thematic elements of the individual confession letters were so repetitious that they formed a grammar of their own as mentioned above, and some prisoner-writers came to actually believe in what they wrote.

9See Kim San and Nym Wales, 233–237. Arirang is an excellent source for information on the realities of the infamous Japanese police torture techniques. 10Ibid., 229. Kim San relates how after his arrest, the police forced him to write down his personal information in detail and to describe his activities from his childhood onward. See Kim San and Nym Wales, 229. 11See Kim P’albong, Na ŭi hoegorok (My memoirs), 8.

KAMSANGNOKAND THE GRAMMAR OF CONVERSION

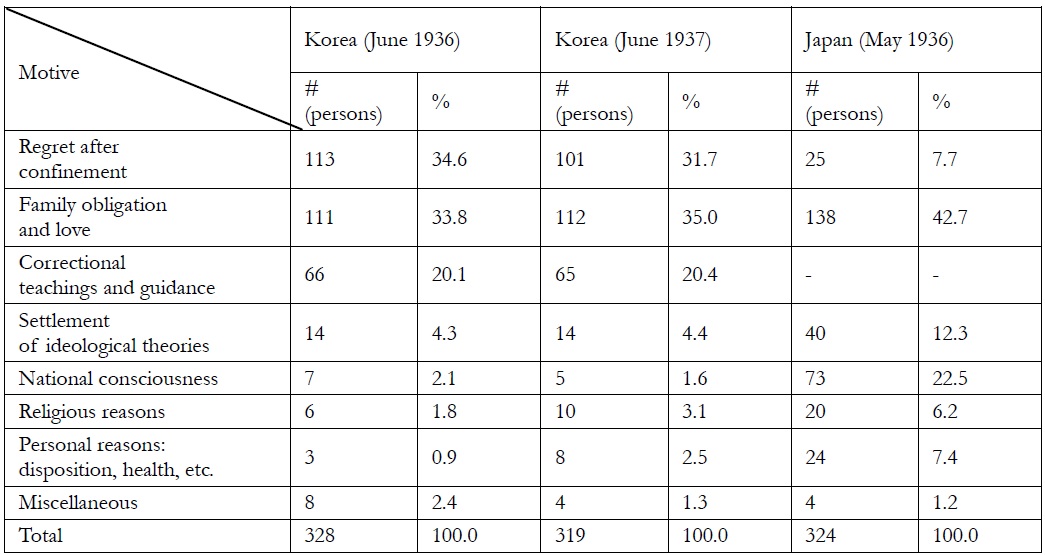

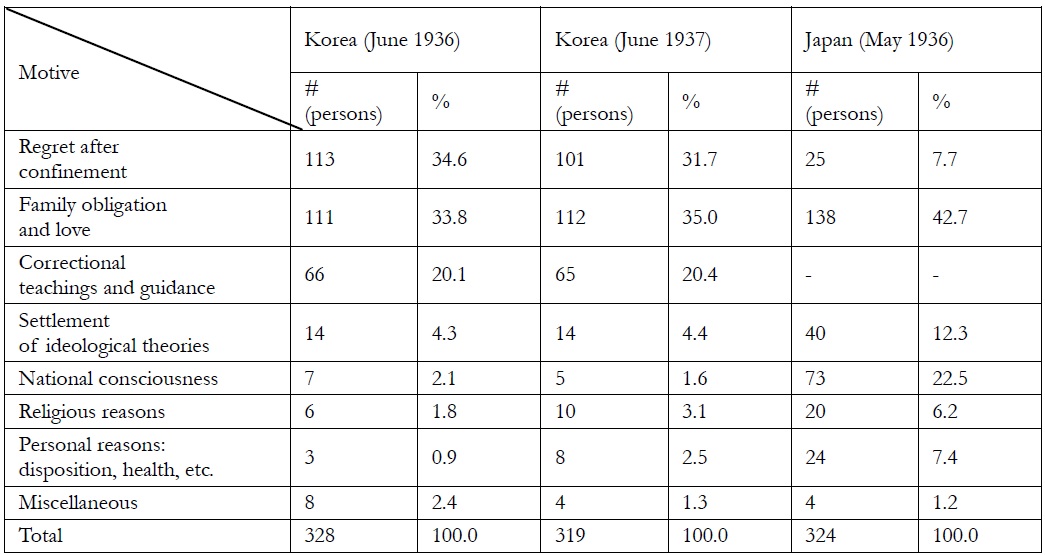

It is difficult to extract statistically meaningful data on the political prisoners’ motives for conversion based on the number of relevant documents remaining today. However, we can take a look at the result of polls taken by the Police Affairs Division of the Government-General of Korea. In the surveys it conducted, Japanese and Korean political prisoners, those categorized as “converts” and “semi-converts” were asked about their motives for conversion.

[] Motives for Ideological Conversion by Korean and Japanese Political Prisoners12

Motives for Ideological Conversion by Korean and Japanese Political Prisoners12

The

I will now examine three sample conversion narratives from the NIHK archive. While all the conversion narratives are written in a similar manner and serve more less the same function, the three I have chosen are particularly well written and representative of the conversion grammar pertinent to the discussion of this article. The authors, Paek Namun, Yi Sunt’ak, and No Tonggyu were the three principals involved in the “red professor” case13 of the Department of Business Administration at Yŏnhi College, now Yonsei University.

Paek Namun submitted his confession letter entitled “Kamsangnok” (Record of impressions) to his pre-trial hearing judge at the Kyŏngsŏng District Court in May 1939. In it he states, “There is no commentator of modern affairs who does not recognize the harmful influence of capitalism. However, I have come to believe that the way to redress the situation is not at all found in communism, or in the ‘privileges’ accorded to communism only.” Commenting on contemporary leftist discourse on the likely collapse of capitalism, he dismisses it by saying, “there will not be the slightest tremor in the fundamentals of the command economic structure of late.”14

Yi Sunt’ak prepared his “Kamsang chŏnhyangnok” (Record of impressions of conversion”) in June 1939. He cites original works of Franz Oppenheimer and other economists to support his view that “Mass production narrows the limits of competition, and thereby predicts the levels of demand for useful products, and thus makes it easier to control production.” Based on this premise, he argues that the “manifestation of paternalism, implementation of social policies, and strengthening of the command economic system”15 in capitalist economies were deterring the expansion of proletarian revolutionary solidarity.

On the issue of Korean national identity, Yi also comments as follows:

He further explains, “It is not at all absurd but instead profitable for Korea to become a nation bumping shoulders with other leading nations in the world by surviving and advancing under the guidance of Japan, whose culture is refined and whose people are strong.”16 Later in the same “Kamsang chŏnhyangnok” Yi adds:

Although Yi makes this statement within the context of the larger argument that differences can be overcome because there are points that are “common to both Japanese and Korean people,”17 his statement nevertheless implicitly acknowledges the distinctiveness of the Korean identity.

The conversion narratives of both Paek and Yi extol the virtues of the Japanese spirit on the surface. They also embrace the imperial Japanese discourses on “command economy” and “ethnic harmony.” On the surface, they could be read as signs of a wholesale renunciation of Marxism on the part of these writers. However, they were an attempt to seek a new ideological foundation, or an attempt to integrate the universal in Marxist theory with what Paek and Yi considered were particular in the Korean situation. In other words, the “conversion” on the part of the intellectuals such as Paek and Yi during this period was in part a critique and rejection of the dogmatism of the Communist International (Comintern, 1919–1943),18 and their embrace of the imperialist discourse on “ethnic harmony” was in fact their acceptance of cultural particularism. Their logic of conversion illustrates the critical boundary, or the minimum logical contradiction, within which Korean Marxists and nationalists could undergo a “conversion” while still maintaining their ideological com-mitments.19 This logic is in fact the key to understanding the literary paths taken by

Paek also compares his earlier scholarship on historical materialism to the phenomenon of “falling in love.” He laments that “Love is supposed to be blind. It is possible that my capacity for sound judgment became a hostage to the state of emotional excitement. As for Marxist historical materialism itself, I did not have the presence of mind to even critically re-read it, because I was in a state of mind where I mistook a pockmark for a dimple.” Following that, he emphasizes the need to pay attention to Korean and Asian particularities; he argues that to the extent that historical “particularities” and “constraints” are acknowledged, “a serious counter-critique must be applied to the Marxist theory of history.”21 Implicit in such writing is the author’s re-evaluation of Western modernity, including Marxism, as well as a re-evaluation of what was once considered tell-tale signs of Asiatic deficiency, or underdeveloped modernity.

Examples of such reinterpretation of Asian self-identity can be seen in the literary works by former members of the Korea Artista Proleta Federatio (KAPF). For example,

The

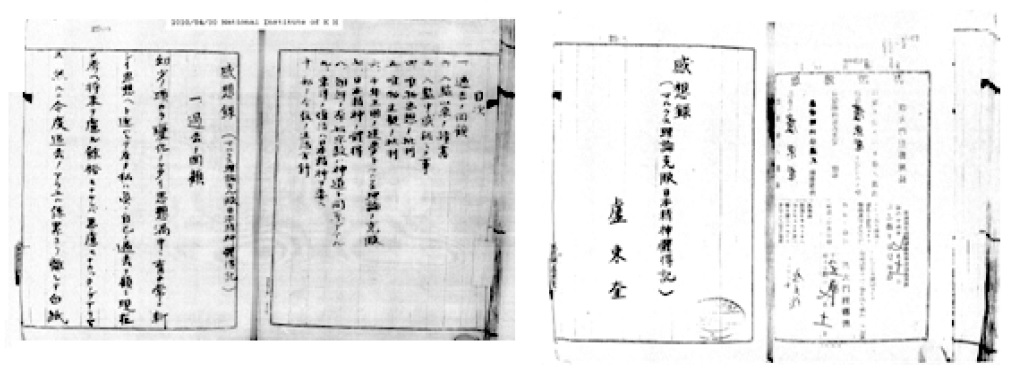

I now turn to No Tonggyu and his “

Paek Namun and Yi Sunt’ak wrote their conversion papers, paying homage to the imperial discourses on command economy and racial harmony at the critical edge of censorship acceptable by the colonial authorities. In contrast, the conversion narrative of No Tonggyu exemplifies the “positive” discourse the authorities wished to disseminate actively.

No’s

In Chapter 125 of his

In Chapter 2, he writes that it is his duty to “comment on the fallacies of Marxism based not on simple impressions but on theoretical grounds and, at the same time, to understand and master the Japanese spirit.” He extols the greatness of Japan by citing two books. The first is

In Chapter 3, No cites two levels of family ties that played a pivotal role in his conversion. The first is his relationship with his father. He explains the relationship between filial piety and one’s allegiance to nation with the notion that family and nation are one and the same. He further explains that to go back to his Confucian family precepts is to go back to embracing the Eastern spirit, and that it is, in turn, a way of mastering the Japanese spirit. The second family tie is his relationship with his eldest son, Chŏngwŏn, who is in the sixth grade at the time of his writing. His son’s visit to Ise Grand Shrine (Ise Jingu) No says, provided him with his second reason for conversion. No states that while he himself is a criminal who has sinned against the state, his son visited the Kashihara Shrine and the Kotai Shrine as an elementary school delegate representing Korea. No reports with great joy and pride that his son marched at the head of a throng of worshippers and that the event was broadcasted to the entire Korean elementary school population.

In Chapters 4 through 9, No presents his critique of Marxism and his personal theory of the analogous relationship between the Japanese spirit and prehistoric religions of Korea, on which he bases his own mastery of the Japanese spirit. The writings in these chapters are interesting, but for the purposes of this article, I will now take a look at Chapter 10, entitled “Future guidelines for living.” He writes, “I have completely severed myself from Marxism and have mastered the Japanese spirit. My future plan for life is to find gainful employment and to wholly dedicate myself to the duties of my station, to pay back even one ten-thousandth of the debt I owe to the country.” He further pledges that he will “completely divest himself of any trace of being an abstract person” and “become a historical Japanese, first,” and thus become “a loyal and honest citizen of imperial Japan.” He concludes his

No’s

12Matsuda, “Shokuminchi makki Chōsen ni okeru aru tenkōsha no undō: Kang Yŏngsŏk to Nihon kokutaigaku–Tōa renmei undō” (The activities of a convert in late colonial Korea: Kang Yŏngsŏk and Japan Kokutai studies—the East Asian Alliance Movement), 133. 13Not all political prisoners in colonial Korea were Marxists. There were also various stripes of nationalists. However, the conversion papers left behind by nationalist intellectuals, in general, tend to lack intellectual rigor and a sense of urgency. In this article, I thus focus on conversion documents authored by well-known Marxists of the time. 14Paek, “Kamsangnok” (May 30, 1939) in NIKH, 2829. 15Yi, “Sasang chŏnhyangnok” (Record of ideological conversion) (June 23, 1939), in NIKH, 2888–2889. 16Ibid., 2866–2867. 17Ibid., 2898–2899. 18For example, we can witness the wartime conversion of Korean Marxists through the case of Im Hwa (1908–1953), an active leftist poet and an early leader of KAPF, who rejected the dogmatism of the Comintern and embraced the notion of Korean particularism during this period. In the earlier period, Im Hwa did not accept such a notion and took a negative stance against intellectual efforts to place special status on Korean identity. With the subsequent change of his position, he accepted “interest in unique cultural classics and traditions” as “reconsideration against portability and internationalism.” He himself then founded a publishing company and worked on publishing the Chosŏn mun’go (Books on Korea) series and devoted himself to systematically classifying Korean traditions and culture. 19It was a matter of course for Korean socialists who “converted” in the 1930s to locate the welfare and happiness of the nation within the theoretical framework of Marxism. For a more detailed discussion on this subject see Matsuuda, “Shokuminchi makki Chōsen ni okeru aru tenkōsha no undō: Kang Yŏngsŏk to Nihon kokutaigaku–Tōa renmei undō” (The activities of a convert in late colonial Korea: Kang Yŏngsŏk and Japan Kokutai studies—the East Asian Alliance Movement). Also, some scholars interpret the championing of the Japanese discourses on command economy and racial harmony by Korean intellectuals during the war period as the continuation of the National United Front of the 1930s, albeit in a warped form. For further discussion on this topic, see Hong, Senjiki Chōsen no tenkōshatachi: Teikoku/shokuminchi no tōgō to kiretsu (Converts in wartime Korea: The unity and division of empire/colony). 20By mid-1940s, towards the end of colonial rule, many forms of literary works come out in Korea that show odd mix-matches of ideas verging on the schizophrenic. In such works, the writers try to preserve their former ideological allegiances while also trying to accommodate the official discourses of Imperial Japan without contradiction. For further discussion on the topic, see Chŏng, Tongyang ron kwa singminji Chosŏn munhak (Discourse on “The East” and literature in colonial Korea). 21See Paek, “Kamsangnok” (May 30, 1939) in NIKH, 2826–2827. 22No Tonggyu, “Kamsangnok: Maksŭ chuŭi iron kŭkpok Ilbon chŏngsin ch’edŭk ki” (Kamsangnok: Overcoming Marxist theory and acquiring the Japanese spirit), in National Institute of Korean History, Yi Sun-t’ak oe i myŏng ch’ian yuji pŏp wiban (Yi Sun-t’ak and two others: Violation of the Public Security Maintenance Law). This Kamsangnok also appears in the “Miscellaneous” section of Shisō ihō, No. 23, June 1940, along with the following editorial note: “This article is a report that has been selected from essays written by No Tonggyu, formerly a professor at Yŏnhi College who is currently being tried at the Kyŏngsŏng District Court for his involvement in the campus communization movement. It had been sent [earlier] to the pre-trial hearing judge.” In this article, I use the copy that appears in Shisō ihō. 23For further detail on this subject, see Kŏmnyŏl Yŏn’guhoe, Singminchi kŏmnyŏl: Chedo, t’ekssŭtŭ, silchŏn (Colonial censorship: Institution, text, practice). 24On this subject see Han, “Kŭndaejŏk munhak kŏmnyŏl chedo e taehayŏ” (On the modern institution of literary censorship), 8, 44. 25No’s Kamsangnok consists of ten chapters. Their titles are as follows: 1) Recollection of the past; 2) Post-imprisonment readings; 3) Events of great impression that occurred during my imprisonment; 4) Critique of materialism; 5) Critique of historical materialism; 6) The illusion of the millennial kingdom and overcoming Marxism; 7) Mastering the Japanese spirit; 8) The native religions of Korea have the same root as Shintoism; 9) The revival of the East demands the Japanese spirit; 10) My future life plan.

DISRUPTING CENSORSHIP: THE IDENTITY OF ABSENCE IN KIM NAMCH’?N’S CONVERSION NOVELS

In recent years numerous new studies on Kim Namch’ŏn (1911–1953?), too many to individually mention here, have come out. The arguments are fascinating, and the works represent a variety of perspectives. What I wish to add here is that Kim Namch’ŏn’s conversion novels, in terms their contents and form, must be understood in the context of the institutionalized conversion narratives examined in this article, and in the broadest possible context of the state censorship apparatuses that oversaw the production of the institutionalized conversion narratives.

As a student in Japan, Kim Namch’ŏn became acquainted with Ko Kyŏnghŭm, Sŏ Insik, and others who were known as the “Marxist-Leninist Faction.” At the time of his arrest in Korea in 1931, he was an active member of this faction. He spent two years in jail and was released on bail in 1933 on the grounds of illness. Like the other two members of the faction, he announced his conversion at court.26 No record of his statement exists today, but like many of his contemporary political prisoners, it is likely that he also was forced to write confession letters in prison.

The most distinctive aspect of his work from the 1930s and 1940s is the divided self, or the ubiquitous presence of many authorial selves in the protagonist(s) and characters within and across different works. I argue that this must be understood in connection with his prison experience and the writing of conversion narratives.

Kim Namch’ŏn was keenly aware of state surveillance and censorship even as his writings closely followed the official grammar of conversion. He tried to find ways to keep his authorial self from being caught by the censorship gaze and experimented with narrative contents and style. This experiment defines and drives his late work from the 1930s and 1940s.

From very early on, after his release from prison in 1934, Kim Namch’ŏn practiced appropriating and re-contextualizing the official conversion grammar. Of his many works that illustrate this literary experimentation, discussion of his work in this article will be limited to that of

The first letter in the novel is “Dear Editor-in-Chief at Inmunsa.” This letter describes how the protagonist came to write a novel. Chang had stopped writing novels after his conversion when he became “gainfully employed.” Yet his friend, Ch’oe Chaesŏ, the Editor-in-Chief and Publisher at Inmunsa, a publishing company, then suggests that Chang “write a novel based on his current philosophy of life and experience.”28 Ch’oe is not only a friend but also a former comrade. They were both members of the group that worked on the publication of the journal

The one non-epistolary section of the novel is entitled “Ch’okt’ak pohosa Kunimoto Shoken-ssi wa na” (Mr. Kunimoto Shoken, the probation officer, and I). Understanding the probation officer system is one of the prerequisites for reading

In December 1936, the colonial state promulgated an enforcement decree on the Korean Political Prisoners Probation Law. The stated purpose of the law was to make sure that Korean political prisoners achieved “perfect national consciousness” and “an established livelihood.” Probation officers were usually a locally influential person whose task was to monitor former prisoners. In comparison to the infamous Public Order Maintenance Law, the new law focused on “probation” or “protection.” At least on the surface, it seems less draconian than the earlier law. However, if the scope of censorship was limited to what was printed in the mass media under the earlier law, the new law shifted and expanded the sphere of censorship from the corridors of government administrative offices to everyday spaces of living and social interaction. Furthermore, it forced writers—former political prisoners—to find full-time jobs. Furthermore, under the regime of the Probation Law, the writer was constantly exposed to “protective observation” and surveillance, forcing the writer to internalize censorship. One can better appreciate the ominous power of the Probation Law in the context of the passage of the Korean Political Prisoners Preventive Detention Law in 1941. The Preventive Detention Law allowed authorities to detain as a “preventive” measure anyone in Korea whose ideology was “in doubt.”

This, then, is the life of the protagonist portrayed in

As is evident in the editor’s comment,

The next letter in the novel is addressed to Kim, a young man who is currently living as a farm worker but who “has a fire-like passion and razor-sharp fastidiousness about literature.” It is implied that Kim has “a sympathetic feeling akin to indignation” concerning Chang’s current conditions of life, and he is opposed to “full-time employment by literary writers.” In his reply to this young man, Chang writes that he was sometimes “forced to write meaningless articles, reluctantly author a vulgar novel, and at times visit a celebrity avoided by even a newspaper reporter.”31 He defines his own former literary practice as a “world of excessive production.” Along with his critique of the literary world of his generation, Chang emphasizes the importance of ‘livelihood’ in this letter. However, the emphasis here seems to be closer to worry; Chang is concerned that the young man might jump on the half-baked practice of political literature, given that the young man cannot fully dedicate himself to literature.

In referring to the importance of “livelihood,” Chang is both repeating the officially sanctioned narrative and breaking the rules of its grammar. For example, while looking at a young female office worker's hand, which is “holding a long pen in between candle-like fingers and going up and down the long stairs of digits from 100,000 to 1 to calculate a sum with a zero margin of error,”32 Chang is reminded of a “pianist’s hand.” In other words, the protagonist is gainfully employed, but he is also someone who is in “pursuit of the high aesthetics of literature.” In other words, Kim Namch’ŏn juxtaposes the specific and prominent themes of official discourse of conversion—such as “livelihood,” and “gainful employment”—with the concept of the “beauty of labor.” Thus he tries to relocate the official discourse of conversion within the sphere of aesthetics. This signifies Kim’s attempt to de-politicize the ideology of conversion and an attempt to re-contextualize “livelihood.”

In a letter sent to Sin, a fellow writer, Chang criticizes certain practices in contemporary literature and society. For example, he is disdainful of the “attitude” of writers who “immediately jump at introducing a love affair or marriage between a Japanese and a Korean in their work in the name of serving the cause of the

The last letter in the novel is sent to “Sister,” and it introduces a children’s tale, which serves as a key to understanding the entire novel. In this letter, the protagonist tells a story to his son Ch’ang. In the story, God calls Right Hand, a good-for-nothing who has been poking around here and there since he was kicked out by Goddess. God then orders him, “Go down to Earth. You shall stand naked on a mountain top so that I may fully observe humanity exactly as you see it.” The son falls asleep while listening to the story, but “I,” the narrator, whispers to himself, “To do that, go to any young woman upon your arrival on Earth and whisper into her ears in a low voice, ‘I want to live.’”33

What does the narrator mean by “I want to live”? According to Ch’oe Chaesŏ, this refers to the “promise of the birth of something new” that emerges when “a man who spent his youthful years in abstractions, ideals, and rationalism opens his eyes to employment, family, and child.”34 This is the meaning of

However, to a different reader who reads the re-contextualization and appropriation strategy in Kim’s work, the same shout is heard as a dissonance, a fracture in the rigidity of the official language and of the mainstream discourse. In this way of reading, the

26One infers from the following newspaper article that his conversion was official: “A hearing on Ko Kyŏnghŭm and three other defendants on charges of violating the Maintenance of Public Order Law began in the morning of July 20. There was a long testimony of Ko Kyŏnghŭm’s exposition on his conversion, which continued until July 21, on which day the court opened at nine in the morning. By eleven o’clock in the morning, hearings on the defense of all four defendants were completed. Three of the defendants, Ko Kyŏnghŭm, Kim Samkgu, and Kim Hyosik, declared their ideological conversion and stated that they would devote themselves to family life upon returning home…” (Chosŏn Chungang Ilbo, July 22, 1934.) Kim Namch’ŏn was Kim Hyosik’s pen name. 27Kim, “Tŭngbul,” 111. 28Ibid.,106. 29Kim, “Tŭngbul,” 121. 30Ch’oe Chaesŏ, “Henshu o ryokute” (Editing finished), 190. 31Kim, “Tŭngbul,” 111. 32Ibid., 109. 33Ibid., 125. 34Ch’oe Chaesŏ, “Kokumin bungaku no sakkadachi” (Writers of national literature).

CONCLUSION: CONVERSION AND CENSORSHIP, AND APPROPRIATION OF DOMINANT SOCIAL NORMS

Studies on colonial-era censorship since the 2000s provide a useful perspective on understanding literature from this era. They have shown that arts and literature during this period were exposed to a double censorship system. They were directly censored by the state through the Office of the Governor-General of Korea, and less directly by market capital through the publishing industry. The studies also show how writers developed ways to deal with censorship besiegement through their narrative strategy.35 This article tries to take advantage of the results of these studies.

Studies on conversion so far have not focused on the legal process of conversion and the conversion narratives produced in the process. Forced to write directly under the watchful eyes of the state agents in the prison, many prisoners chose to maintain their beliefs, albeit in a roundabout and warped form, by producing texts that satisfied the state requirements. The inclusion of the themes of livelihood, job, and family, for example, and the discussion of the merits of command economy and the theory of racial harmony are examples of such efforts.

In the case of literary writers, these former prisoners appropriate the experience of such prison writing in their conversion novels outside of the prison. As we can see in the case of Kim Namchŏn, he appropriates the dominant interpretation of “livelihood,” or “living,” for example, and recontextualizes it as a basis for criticizing the dominant ideology. In this way he satisfies the requirements of the censorship apparatus but at the same time undermines it and deals a blow to it. Accordingly, the standard for evaluating a conversion novel in Korea can no longer be the level of the intensity of its conversion. Instead, the focus of the evaluation should be on the legal and material conditions of the conversion, on the author’s narrative strategy for dealing with the conditions, and on the subjectivity of the author.

35See for example, Kŏmnyŏl Yŏn’guhoe, Singminji kŏmnyŏl: Chedo, t’eksŭtŭ, silch’ŏn (Colonial censorship: Institution, text, practice).