Gender is clearly visible, highly influential, and linked to sexuality in sport. It may be argued that gender ideology is exaggerated, and that sexuality is more closely tied to gender ideology in sport than on other social contexts. As several scholars in gender and sport studies argue (e.g., Coakley, 2007; Krane, 2001, 2008; Messner, 1988, 1996) gender ideology is prominent and persistent, and even celebrated in sport. Nearly all sport activities, and particularly those at the elite, competitive levels sex-segregated. Sport is inherently a masculine activity that highlights competition, aggression and striving to be swifter, higher and stronger (

The close association of sex, gender and sexuality in sport suggests that sport is a particularly hostile environment for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgendered (LGBT) sexual minorities. LGBT discrimination in the form of harassment, exclusion and inequity is found in education, health care, employment – and in sport. Such harassment and discrimination has negative effects on LGBT individuals, and also on other participants and programs.

Several reports and some studies provide evidence of the hostile climate in sport for sexual minorities and those who do not conform to gender ideology. Many sport scholars (e.g., Griffin, 1998; Plummer, 2006) describe sport as one of the most homophobic social arrangements and many anecdotal reports show sexual minority athletes stigmatized or discriminated against through negative stereotypes, social isolation, and harassment. Griffin, Krane, and their colleagues (e.g., Griffin, 1998; Kauer & Krane, 2010; Krane, 2001, 2008; Krane & Barber, 2005) have documented the hostile environment for sexual minority athletes and coaches in U.S. sport, and drawn conclusions and recommendations for policies and practices to create more inclusive space for LGBT people in sport. Similar reports document the hostile climate and offer recommendations for sport in Canada (Demers, 2006) and in the UK (Brackenridge, Allred, Jarvis, Maddocks, & Rivers, 2008). A recent, comprehensive study in of LGBT people in Australia (Symons, Sbaraglia, Hillier, & Mitchell, 2010) found a hostile climate in sport, especially for male participants, and that the very large percentage of participants had experienced harassment in sport. Still, the participants reported benefits of participation in sport. Symons et al. concluded by noting that sport is valued and beneficial, and they offered recommendations to improve access for all.

Those reports document a hostile environment for sexual minorities and offer valuable insights and guidance for policies and practice. However, nearly all the reports are from western, English-speaking countries. In Asian countries, and particularly in Taiwan, sexual minority issues have been ignored. Also, most studies focus on perceptions and experiences of LGBT athletes, which is obviously important, but there is little research on attitudes of the wider range of participants. In the current study, we specifically focus on the attitudes of the wider range of college athletes and coaches to gain further insight into the climate for sexual minority athletes in Taiwan. Specifically, the present research examines athletes’ and coaches’ attitudes toward sexual minority athletes in Taiwan, and explores predictors of those attitudes.

>

Attitudes toward Sexual Minorities

Attitudes toward sexual minorities have changed remarkably over the past two decades, and continue to change, but sexual minority individuals continue to experience considerable discrimination and hostility (Herek, Gillis, & Cogan, 2009). U.S. national surveys on school climate for LGBT youth in the U.S. (e.g., Kosciw & Diaz, 2006; Kosciw, Diaz, & Greytak, 2008; Kosciw, Greytak, Diaz, & Bartkiewicz, 2010; Rankin, 2003) also indicate a persistent, hostile environment for LGBT youth and suggest organized sport is a particularly homophobic setting. Research specifically on the climate in sport is limited, but Brackenridge, Rivers, Gough, and Llewellyn (2006) found that homophobic bullying of young people deters participation ion sport.

Only a few studies have specifically examined attitudes toward sexual minority people within the context of sport. Gill and her colleagues have conducted several of those studies. Morrow and Gill (2003) found that most physical education teachers (61%) and both LGB and straight students (91%) witnessed heterosexist and homophobic behavior. In subsequent research, Gill, Morrow, Collins, Lucey, and Schultz (2006) surveyed undergraduate Exercise and Sport Science students on attitudes toward gay men and lesbians and other minority groups and found evaluation scores were markedly lower and more negative for gay men and lesbians than for other minority groups (e.g. ethnic minorities). In another study, Gill, Morrow, Collins, Lucey, and Schultz (2010) examined the perceived climate for LGBT youth as well as other minority groups in three physical activity settings (physical education, organized sport, exercise). Consistent with national surveys indicating high levels of homophobic remarks and little intervention in physical education and sport settings, they found a hostile climate for LGB youth, with sexual minorities and people with disabilities more likely to be excluded than other minority groups.

Roper and Halloran (2007) assessed attitudes toward lesbians and gay men in relation to the student-athletes’ gender, sport and contact experience; they found that male student-athletes were more negative in their attitudes toward gay men and lesbians than female student-athletes, and student-athletes who indicated having contact with gay men or lesbians had more positive attitudes. Roper and Halloran also called for more research on sport-specific aspects of athletes’ attitudes, the quality of contact experience and coaches’ attitudes. All of these studies on the climate in sport, and most psychology research on attitudes toward sexual minorities have been done in the U.S.

As noted earlier, sexual minority issues are largely ignored and no research has specifically examined attitudes toward sexual minorities within the context of sport in Taiwan. The U.S. supported Chiang Kai-Shek’s regime in Taiwan beginning in 1949, and Taiwan continues to have a strong American orientation. The LGBT rights movement began in Taiwan in the 1990’s; the first legally registered gay organization, Taiwan Tongzhi Hotline Association, was established in 1998 and organized the first gay pride parade in 2003 (Taiwan Tongzhi Hotline Association, 2005). At the same time, Taiwan has longstanding cultural and religious traditions that highlight relationships and filial piety (Chou, 2001; Simon, 2004). Wang, Bih, and Brennan (2009) found filial piety played a central role in gay men coming out to their parents. Both those traditional cultural values and connections with western, U.S. culture likely influence the climate for sexual minorities in Taiwan, but we have little research. Although no research has specifically examined attitudes toward sexual minorities within the context of sport in Taiwan, Hou et al. (2006) examined the attitudes toward homosexual individuals and intention to provide care among psychiatric nurses in southern Taiwan. They found psychiatric nurses who had higher education degrees, higher levels of knowledge about homosexuality, and homosexual friends or relatives had more positive attitudes and also had a higher intention to take care of homosexual people in their nursing practice. Liao’s (2007) master thesis, which is the rare work on sexual minority issues in Taiwan, explored the experiences and identity formation process of gay student-athletes in Taiwan. The participants in his interviews described attitudes within the sports organization as full of “misogyny” “homophobia” and “sissy-phobia”.

The current study empirically examines attitudes toward sexual minority athletes within the context of sport in Taiwan with a larger sample of both athletes and coaches to provide a more accurate picture of the climate and to explore factors affecting people’s attitudes.

>

Functional Approach to Attitudes toward Sexual Minorities

As well as looking at attitudes toward sexual minorities, we also explore why people hold particular attitudes using Herek’s functional approach as a framework. Herek (1984, 1986, 1987) identified three major functions met by individuals’ attitudes toward sexual minorities, and distinguished three types of attitudes according to the social psychological functions they serve: experiential-schematic function, self-expressive function and defensive function.

The experiential-schematic function implies that individuals’ attitudes toward sexual minorities are based on past contact experiences. Attitudes serve as part of cognitive schema in organizing past experience and providing a guide for future contact. Previous research showed that contact with sexual minorities or having LGBT friends was a major predictor of attitudes (Altemeyer, 2002; Herek & Capitanio, 1996; Roper & Halloran, 2007). Thus, the present research examines feelings (negative-positive) about past contact experience as a predictor of individual’s attitudes.

Attitudes serve a self-expressive function by expressing values important to one’s concept of self. Thus, attitudes help individuals to establish their identities while mediating their relationship to other important individuals and reference groups. Individuals’ values/ beliefs are major predictors of attitudes under this function. Previous studies found that people who had stronger religious beliefs and traditional gender role concepts had more negative attitudes toward LGBT people (Herek, 1984; Herek & Capitanio, 1996; Weinberger & Millham, 1979). As discussed earlier, sport reinforces conventional gender roles, fosters sexism, and supports patriarchy (Coakley, 2007; Griffin, 1998; Harry, 1995; Messner, 1988). Thus, the present research proposes sport gender ideology (the degree of belief that men in sport should show their masculinity and women their femininity) is a predictor of individual’s attitudes.

Attitudes serve a defensive function for coping with inner conflict and anxiety. The inner conflict results from an individual’s insecurity in sexual identity, especially when facing same-sex homosexuals. Thus, the present research considers sex of both participants and attitude targets.

The purpose of the present research is to examine athletes’ and coaches’ attitudes toward sexual minority athletes, and explore predictors of attitudes based on Herek’s functional approach with past contact experience and sport gender ideology as predictors of attitudes toward gay and lesbian athletes. The primary research question is: Do past contact experience and sport gender ideology predict attitudes toward sexual minority athletes? The question was examined for both coaches and athletes in six combinations. Because of the sex segregation in sport, we did not examine male athletes’ attitudes toward female lesbian athletes or female athletes’ attitudes toward gay male athletes, but focused on relationships more relevant to their daily interactions. Following are the specific relationships examined in the primary research question, “Do past contact experiences and sport gender ideology predict attitudes toward sexual minority athletes.” For athlete participants, we examined the following combinations:

We hypothesized that both past contact experience and sport gender ideology would predict attitudes toward sexual minority athletes in all cases. Because no research has examined the combined influence of these two factors’ effects on individual’s attitudes we also considered the possibility that there might be an interaction effect between these two predictors. For example, it might be that people with stronger gender ideology are less influenced by past contact experience.

In addition to examining the relationships for the primary research question, we also used descriptive and exploratory analyses to compare attitudes, past experience and gender ideology of male and female athletes as well as male and female coaches. Although previous research in sport is limited, some studies suggest that men hold more negative attitudes than women, and that attitudes toward gay men are more negative than attitudes toward lesbian women.

To address the research questions, survey methods were used. Survey measures of gender ideology, past contact experiences and attitudes toward gay and lesbian athletes were administered to collegiate athletes and coaches in Taiwan.

1) Athletes. The athlete participants in the present study included 205 male (mean age= 20.56, SD=1.49) and 185 female (mean age =20.84, SD=1.92) collegiate student-athletes in the top level, equivalent to U.S. NCAA Division I, who participated in several sports. Specifically, the sample included both male and female athletes in soccer (male, n=18; female, n=32), handball (male, n=16; female, n=23), basketball (male, n=26; female, n=36), baseball (male, n=26; female, n=6), Tae kwon do (male, n=24; female, n=21), Wrestling (male, n=14; female, n=8) and Judo (male, n=34; female, n=22), and only female athletes (n=20) in Softball and only male athletes (n=24) in Rugby. Data for 23 male athletes and 17 female athletes were thrown out due to incomplete survey and/or demographic information. Only one male athlete self-identified as bisexual, while 32 (19.3%) female athletes self-identified as homosexual and 24 (14.3%) self-identified as bisexual.

2) Coaches. The coach participants included 56 male (mean age=41.84, SD=9.55) and 45 female coaches (mean age=39.47, SD=8.46) currently coaching college/university sport teams. Data for 3 male coaches and 4 female coaches were thrown out due to incorrect completion of the survey and/or demographic information. No male coach self-identified as bisexual or homosexual, one (3%) female coach self-identified as homosexual and 4 (9.1%) self-identified as bisexual.

The questionnaire packet included a demographic form that asked participants’ sex, age, and sexual orientation (heterosexual, homosexual, or bisexual) and three measures assessing the main variables- attitudes, gender ideology, and past experience.

1) Attitudes toward Gay and Lesbian Athletes. The Attitudes toward Gay and Lesbian Athletes scale was adapted from the Estrada and Weiss (1999) Attitudes toward Homosexuals in the Military scale. The original scale did not separate attitudes toward gay men and lesbians. In this study, we developed two versions (attitudes toward gay male athletes version and attitudes toward lesbian female athletes version). The full questionnaire consisted of 14 items; with 12 items reworded to fit the sport setting. For example: Allowing openly gay and lesbian people in the armed forces (reworded to “sport team”) would be disruptive. Two items (I feel that the ban on homosexuals in the armed forces should be lifted; Gay males make me more uncomfortable than lesbians.) were deleted as not fitting the sport setting. Two new items were developed based on Griffin’s (1998) and Coakley’s (2007) works on the climate for LGBT people in sport. The two new items are: Allowing openly gay/lesbian athletes on a sport team will affect the image of the team; it will affect the fairness of the game if there are gay/lesbian athletes on opponent teams. The decisions of (re)wording, deleting and adding items were all made after discussion with an expert in translation, a senior coach and a scholar of sport psychology. Using a six-point scale (1=strongly disagree; 6=strongly agree), higher scores indicate more negative attitudes toward gay male or female lesbian athletes. The measure had a reliability of Cronbach alpha= .83.

2) Sport Gender Ideology. The Sport Gender Ideology Scale was developed based on the Attitudes Toward Women Scale (AWS, Spence & Helmreich, 1973 ), Male Role Norms Scale (Thompson & Pleck, 1986), and in reference to Griffin’s (1998), Messner’s (1988), Kidd’s (1990) and Whitson’s (1990) works on gender ideology in sport. For example, the item: Swearing or physical violence by a female athlete is more repulsive than by a male athlete was based on the original item from AWS: Swearing and obscenity are more repulsive in the speech of a woman than a man. The questionnaire consisted of 25 items using a six-point response scale (1=strongly disagree; 6=strongly agree.) Higher scores indicated stronger traditional gender role beliefs in sport (the belief that men in sport should show their masculinity and women their femininity). All the developed items were discussed with a scholar in gender issues and a scholar of sport psychology. The scale was shown to be reliable with the present sample (Cronbach alpha= .76).

A pilot study was conducted with a sample of 87 undergraduate students, who were studying either in Physical Education or Athletic Department (male=60%) to examine the concurrent validity of this newly developed scale. The “Gender Role Stereotype Scale” (Tsai, 2003, p. 83) was used because it had been translated to Chinese, had a good reliability, and correlated with the AWS (r= .75). The pilot results showed the correlation between this newly developed “Sport Gender Ideology Scale” and “Gender Role Stereotype Scale” was .73 (

3) Past Contact Experience. Past contact experience was a two-step question. First, participants were asked whether they had ever had contact with gay men or lesbians (if “yes”, the score was 1; if “no”, the score was 0). Participants who responded “yes” then continued to answer the second step question: How did you feel about your past contact experience generally? (using an 11-point scale; from very bad= -5 to very good= 5).The final score for past contact experience was the product of first score and second score ranging from –5 to 5.

Individual coaches were initially contacted by the first author or colleagues who were also familiar with the purpose of present research. After attaining permission of coaches, questionnaires were administered by the first author or colleagues to coaches and athletes who were interested in participating in the 15 minutes before or after regular practice. First, researchers explained the purpose of the study, that the questionnaire was anonymous, that responses were only used for academic research, and that participation was voluntary; then researchers explained the questionnaires and asked participants not to talk to each other or look at others’ questionnaires while filling out the questionnaires. After completing the questionnaires, participants folded them and put them in a questionnaire-collection box themselves.

Before addressing the primary research question, descriptive analyses were conducted on attitude and predictor measures. Also, male and female athletes and male and female coaches were compared with exploratory analyses. Hierarchical regression was employed to determine if sport gender ideology and past contact experiences predicted attitudes toward homosexual athletes. The dependent variable was attitudes toward sexual minority athletes. Sport gender ideology and past contact experience were assigned as predictors for the block 1 first entry, and the interaction term, which was the product of sport gender ideology and past contact experience, was assigned as the block 2 second entry.

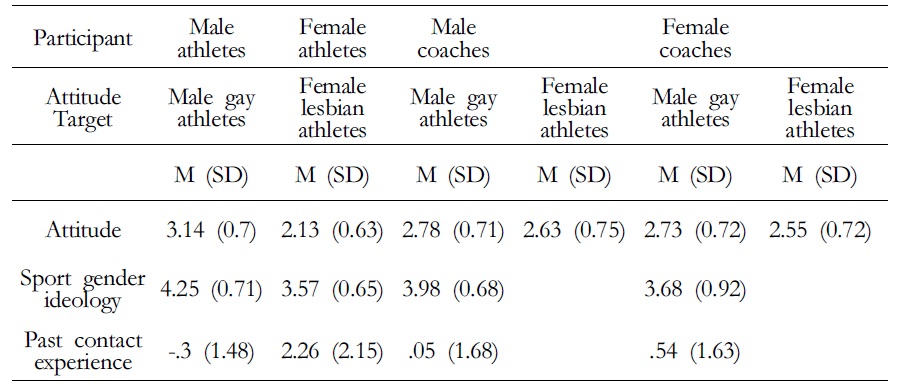

Table 1 includes descriptive results (Mean and SD). As table 1 indicates, male athletes’ attitudes toward gay male athletes were slightly negative (M= 3.14); whereas female athletes’ attitudes toward lesbian female athletes were more positive (M= 2.13). As exploratory comparisons, one-way ANOVA with follow-up post-hoc tests were conducted to examine the differences in attitudes and gender ideology among the four groups (male and female athletes, male and female coaches). Results showed that for the attitudes toward gay male athletes, male athletes’ attitudes were more negative than female coaches’ attitudes (

[Table 1] Descriptive Results: Means (SDs)

Descriptive Results: Means (SDs)

In terms of past contact experiences, only 67 (36.9%) male athletes indicated having contact with sexual minorities; whereas 142 (84.6%) female athletes indicated having contact with sexual minorities, and the mean of their past contact experience was positive at 2.33 (SD= 2.28). For male coaches, 32 (60%) had ever had contact with sexual minorities, and the mean evaluation of their past contact experience was -0.02 (SD= 1.91). For female coaches, 27 (64.7%) had ever had contact with sexual minorities and the mean evaluation of their past contact experience was positive at 3.68 (SD= 0.92).

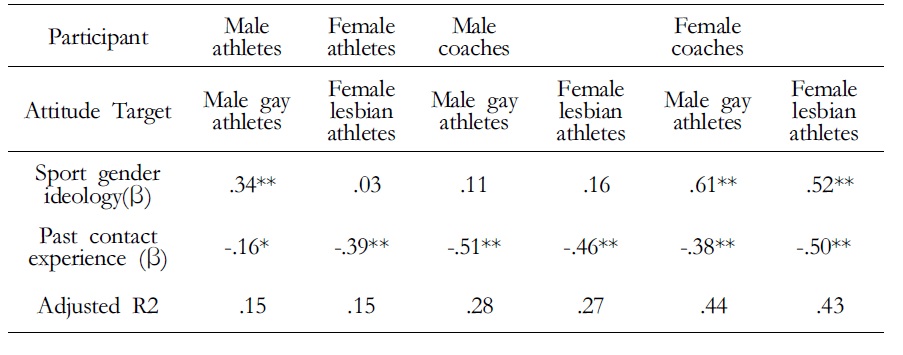

The hierarchical regression analysis revealed no interaction effect in step 2 in any of the six conditions, but main effects were found in step 1. As table 2 shows, for male athletes, both sport gender ideology and past contact experience contributed significantly to the prediction of attitudes toward gay male athletes (R= .40, F(2,173)=16.44,

Hierarchical Regression Results: The standardized regression coefficient (β) and adjusted R2 in step 1

For male coaches, only past contact experience contributed significantly to prediction of their attitudes toward gay male athletes (R= .56, F(2,42)=9.57,

The purpose of the present research was to examine athletes’ and coaches’ attitudes toward sexual minority athletes, and explore predictors of attitudes based on Herek’s functional approach. We proposed that past contact experience and sport gender ideology were predictors of individual’s attitudes and considered a possible interaction effect between these two factors. The present research indicated that for male athletes and female coaches, both sport gender ideology and past contact experience predicted their attitudes toward sexual minority athletes with no interaction effect between these two predictors. For female athletes and male coaches, only past contact experience predicted the attitudes toward sexual minority athletes and there was no interaction.

Generally, the results indicated attitudes of both athletes and coaches toward sexual minority athletes were neutral and slightly positive (mean scores were from 2.3 to 3.1 with a 6-point 0-6 scale.) Compared to the studies of Gill et al. (2006) and Roper and Halloran (2007), which both used Herek’s (1994) ATGL-S scale to measure undergraduate students’ attitudes (mean scores were from 13.9/female to lesbian to 18.2/male to gay with a 5-25 scale) and student athletes’ attitudes (mean scores were 11/female to lesbian to 18 male to gay) respectively, it seems that at least male athletes in the current study were less negative about gay athletes. Certainly, one explanation could be the different measures. The items in the attitude measure in the present research were more about equality judgments and less about the individual’s emotional response than in ATGL-S. For example, on one item that did reflect emotional response, 50% of male athletes felt uncomfortable sharing a room with homosexual athletes. Future studies could expand beyond equality items to include individual’s emotional or behavioral responses while facing gay or lesbian athletes.

Past contact experience predicted attitudes in all six conditions. The results suggest that when individuals had more positive past contact experience, their attitudes toward sexual minority athletes were more positive. This finding is consistent with previous findings in non-sport settings (Herek, 1988; Herek & Glunt, 1993; Herek & Capitanio, 1996) and supports Herek’s experiential schematic function. Furthermore, most past studies only addressed past contact and did not assess feelings or perceptions of the contact experience. The present research indicates that quality of past contact experience is important. Herek and Capitanio (1996) indicated that people who knew multiple LGBT people or had close LGBT friends were more likely to recognize the group’s variability, refute inaccurate stereotypes and not make simple judgments about anti-gender roles (e.g. gay men were all feminine and lesbians were masculine). That is, past contact experience moderates the effect of gender ideology on individual’s attitudes toward sexual minorities. More research is needed to determine whether perceptions might mediate or moderate the relationships of past contact experiences and sport gender ideology with attitudes.

We also found sport gender ideology was a predictor of male athletes’ and female coaches’ attitudes, but not a predictor for female athletes and male coaches. One possible explanation for these differences is the participants’ position expectations/role constraints in sport. Male athletes may demonstrate their masculinity in response to peer pressure or coaches’ requirements (Griffin, 1994). Female coaches may also feel pressure to show their conventional gender ideology to avoid trouble in their work (Woods, 1991). On the other hand, sport is a potential area for female athletes to challenge traditional gender ideology. Harry (1995) indicated the meaning of sport differed for men and women. For men, sport highlights gender identification, but for women, sport was less expressive of gender identity. As for male coaches, their privileged status in sport may have allowed them to feel less pressure to demonstrate their gender ideology through negative attitudes toward sexual minorities.

For both male athletes and female coaches, stronger sport gender ideology predicted more negative attitudes toward sexual minority athletes. Previous studies (Herek, 1984; Herek & Capitanio, 1996; Weinberger & Millham, 1979; Whitley, 2001) found that people who expressed traditional, restrictive attitudes about gender roles had more negative attitudes toward sexual minorities. The position expectations/ role constraints of male athletes and female coaches might force them to abide by masculinity-dominated formal and informal rules in sport. As for female athletes, their attitudes toward sexual minority athletes might be a self-expressive function of other values, such as equity or justice. Herek (1987) subdivided self-expressive function into social-expressive and value-expressive functions. In social-expressive function, significant others’ attitudes affect individual’s attitudes. Future studies could explore the relationship between coaches’ attitudes, captain’s attitudes, group climate and individual’s attitudes toward gay and lesbian athletes.

As well as advancing knowledge on attitudes and sexual prejudice, the ultimate goal is to change negative attitudes and eliminate prejudice toward sexual minority athletes. Herek’s functional approach offers some strategies for attitude change. Based on our results, positive contact experience was a key factor, suggesting the desirability of more opportunities for positive interaction with sexual minorities. As Herek (1987) suggested, interactions should occur in situations in which individuals have equal status and common goals with emphasis on similarities rather than sexual orientation. We also found lower sport gender ideology leading to more positive attitudes. This result suggests that significant others, including coaches, parents and sport psychology consultants can help individuals recognize the implicit sport gender ideology and deconstruct some myths in sport. In Taiwan, gender equality education has been addressed in the past 10 years; however, it is not widely disseminated, and definitely not integrated into sport settings. Several national organizations, model programs and resources emphasizing inclusive practice for diverse people, including sexual minorities, in sport settings are available in Western countries (e.g., Women’s Sport Foundation in USA; Canadian Association for the Advancement of Women and Sport and Physical Activity in Canada). Scholars and practitioners could adapt those and develop suitable educational materials in consideration of cultural and historical factors in Taiwan.

There were some limitations in the present research. Four coaches refused to participate in the present study and expressed their discomfort and indicated our study was “questionable” after seeing the questionnaire. In fact, coaches such as these are a target population, and we should make more efforts to explore their attitudes and perceptions. Our measures were also limited. Future studies could separately assess participants’ past contact experience with gay men, lesbians and bisexuals, or add behavioral measures beyond attitudes. Research could be extended to professional athletes or national teams who were more sensitive to image management for financial sponsors. The present research focused on sports that stressed strength, endurance, and might be regarded as male-dominated. The results might not generalize to other sports, particularly those that stress aesthetics or body-presentation, like figure skating and gymnastics.

The present research used Herek’s functional approach to examine past contact experience and sport gender ideology as predicators of attitudes toward sexual minority athletes in Taiwan. We found that when coaches or athletes had positive past contact experiences, their attitudes toward gay and lesbian athletes were more positive, and when male athletes or female coaches had lower levels of sport gender ideology, their attitudes were more positive. The results remind us to take self-expressive values among different groups into consideration in research on attitudes toward sexual minorities, and in developing policies and practices to promote inclusive sport.