FACTORS AND STRATEGIES RELATED TO DEFENSE REFORM

>

FACTORS RELATED TO DEFENSE REFORM

Various factors, or independent variables, can decide the final outcomes of reform in the military. The budget factor stands out as one. However, there is no case where the entire required budget for the reform was provided. An able defense leader can prioritize well and find ways to overcome a budget shortage. The amount of budget affects not the success or failure of the reform but the speed of its implementation. Rosen (1991, 252) argues that there is “no relationship between levels of resources and the numbers of innovations an organization made. . . . the successful innovation examined were initiated in periods of constrained resources at least as often as in periods during which budgets were large and growing.”

The resistance from members of the military—especially senior leaders— could hamper reform efforts. By their very nature, bureaucracies are resistant to change, in particular military bureaucracies, which are usually more conservative than general government bureaucracies. Military bureaucracies can be very resistant to reform-level change. That is why several military theorists insist that civilian leaders must intervene to force change in the military (Teriff, Farrell, and Frans 2010). However, such bureaucratic resistance may be manageable if a reformative leader has the power to decide the promotions of members and the flexibility to accommodate their critics and recommendations (Park 2008). Rosen pointed out that civilian intervention to reduce bureaucratic resistance in the military seems not as crucial as the strategy of military leaders for innovation (Rosen 1991). As long as the top military leaders have their own vision and will for the military reform, they can manage to find the right tools to persuade their subordinates.

One must also consider the influence of political and social factors to military innovation in a country (Rosen 1988). In the case of South Korea, different ideologies of different administrations influenced the defense reforms (Klingner 2013). However, strategy is the key to meeting end goals (U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff 2013, II-5). Political and social factors constitute the environment, which a reformative leader should handle with a creative strategy. “Peacetime military innovation occurs when respected senior military officers formulate a strategy for innovation” (Rosen 1991, 21).

Therefore, I argue that the obstacles to reform discussed above can be overcome as long as a reformative leader has the right strategy. For example, former U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld sped up the transformation of the U.S. military and made significant changes to the U.S. military during his term (O’Rouke 2004; Zakheim 2007), despite having to fight for the necessary budget, spar with generals in the military about the reforms, and persuade the political opposition in the Congress. As Dov S. Zakheim (2007, 26–27) describes:

>

STRATEGIES FOR DEFENSE REFORM

Strategy for a defense reform might involve various elements, such as whether to use a top-down or bottom-up approach, concentrate on a few key fields or cover the entire military, seek civilian help or not, etc. The reformative leader formulates a relevant strategy by making the right choices regarding all the approaches and means for the reform. However, the speed of change—a key feature of any reform—arouses much debate, as evidenced by the recent reform efforts of the U.S. military.

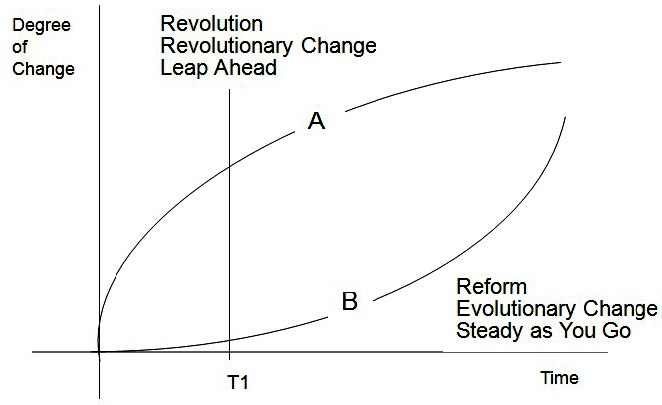

Because the former U.S. Secretary of Defense, Donald Rumsfeld, pursued his defense reform (i.e., “Defense Transformation” or “Military Transformation”) so rapidly, criticisms and debates regarding the speed of change ensued. Most of all, the military community and outside critics harshly criticized Secretary Rumsfeld for the hasty implementation (Murray and O’Leary 2002; Czelusta 2008). Some military theorists conducted research on the right speed of change partly to defend their Secretary. Hans Binnendijk (2002, 76–78) at the U.S. National Defense University contrasted a revolutionary change strategy (“leap ahead strategy”) and an evolutionary change strategy (“steady as you go strategy”), explaining the strengths and weaknesses of both strategies. Leonard L. Lira (2004) at the U.S. Military Academy contrasted a “First-Order Change” and a “Second-Order Change” and defined the transformation of the U.S. military as the latter.

In fact, social scientists have debated over the speed of change. Samuel Huntington (1968, 344) contrasted revolution and reform, explaining that revolution involves “rapid, complete, and violent change in values, social structure, political institutions, governmental policies, and social-political leadership,” while reform involves “changes limited in scope and moderate in speed.” Scholars in business management have also explicated a similar contrast-i.e., ‘revolutionary change’ and ‘evolutionary change’—as means to adapt to changing business environment (George and Jones 2005).

As discussed above, there are two contrasting types of change in reform efforts, which I illustrate in Figure 1.

In Figure 1 above, Curve A initially exhibits rapid changes and later shows a reduced speed of change. Curve B exhibits slow changes early on, with an accelerated speed of change over time. If all the allotted amounted of time for the reform has passed, the two curves would end at the same degree of change. However, if the plan for change is stopped in the middle—for example, at point T1—then the level of achievement would be very different based on the curves applied. While Curve A could boast considerable changes even at point T1, Curve B could show a minimal result because of its slow and long-term implementation schedule.

TWO STRATEGIES OF CHANGE IN DEFENSE REFORM

The militaries, in pursuit of a defense reform, would generally select a strategy between the two types of change (as illustrated in figure 1) in accordance with the external and internal situations. I would like to call Curve A in the figure 1 the “Change and Adjust Strategy (CAS),” which adopts the concept of “revolution, revolutionary change, and leap ahead.” Curve B can be called “Plan and Change Strategy (PCS),” which adopts the concept of “reform, evolutionary change, steady as you go.”

>

TYPE 1: CHANGE AND ADJUST STRATEGY (CAS)

In addition to fostering speedy changes, CAS may prefer a fundamental change by denying the continuation of the current status quo. This strategy aims to make rapid changes across the field. It accepts the side effects of changes as a necessary cost and is ready to deal with the calculated risk.

When challenges cannot be dealt with effectively via a conventional or gradual approach, a speedy and comprehensive change is required. For example, if challenges created by the technological advancements of the Information Age cannot be handled well by a gradual adaptation, the opposite strategy should be explored (Binnendijk 2002). If the problems of a certain military have not been solved by several reform attempts of gradual change, a more speedy and comprehensive strategy should be explored and adopted.

Because the CAS concentrates on the implementation of changes, it can result in considerable achievements in a relatively short period of time. It can spread the culture for change to all the members of the organization and make them a part of that change. It may not allow time for opponents to the planned change to resist. Like flames of fire or a flood of water, the CAS can expedite and expand changes across the organization, achieving a result with little resistance in a short period.

However, the CAS can involve much trial and error in the course of its speedy implementation. One can jump to a conclusion that could turn out to be wrong later and create considerable side effects. Because speedy implementation of the reform is the top priority, such strategy may be unable to organize changes in a systematic and consistent way.

>

TYPE 2: PLAN AND CHANGE STRATEGY (PCS)

The PCS intends to prevent the trial and errors of the CAS through a gradual implementation, in-depth reviews, and open discussions during the reform process. This strategy tends to spend considerable time developing complete plans with detailed implementation roadmaps, and tries to build consensus for the plan among members before implementation. It prefers continuation during the whole time. Because of these moderate characteristics, one might consider the PCS as a safe and preferred strategy.

The strength of the PCS includes a reduced possibility of trial and error, thanks to carefully developed plans and detailed roadmaps. If a negative aspect of change is found, such would be addressed in advance. Every emerging new element is incorporated. One can revise continuously the direction, contents, and speed of changes in pursuit of the PCS. Because of its strong dependency on in-depth discussions and consensus of the reform plan, the PCS is unlikely to make members of an organization anxious about the beginning and end of the reform. The initial investment of time and money in the PCS is smaller than that in the CAS.

However, the most worrisome downside of the PCS is the strong probability of interruption prior to reaching any achievement. Leader or membership changes may occur, or alterations in the environment before full implementation of the planned changes. In addition, with the longer planning process comes the possibility of opposition to the plan growing stronger. The proponents of a reform may be vulnerable to such opposition if achievements are not made in the initial stage of the reform.

>

APPLICATION OF THE STRATEGIES

Without the promise of big and fundamental change, the CAS can hardly get the support of the people and members of the military. The PCS will appear more realistic than the CAS due to its low risk and gradual increase of investment. There is also no guarantee that the adoption of the CAS would create success as promised and result in revolutionary or even significant improvement in capabilities (Blackwell and Blechman 1990).

In theory, the PCS is safer than the CAS because the down payment and risk involved are less. However, in practice, the PCS can be used as an excuse not to change and can be thwarted at any point during its process. The PCS can allow complacency to reemerge in the name of prudence, allowing for open-ended discussions to follow. The PCS tends to strengthen the status quo and devalue the future vision as risky (Conetta 2006). For these reasons, the successful implementation of the PCS is more difficult and requires greater leadership and talent than the implementation of the CAS (Huntington 1968).

The best solution might be to combine the strengths of the two strategies while heeding their weaknesses. However, such is easier said than done. The rhetoric of combining the two can leave reform initiatives stalled because of inconsistency in the reform strategies. The simple combination of these two strategies can ignore the unique situation that a certain military should overcome. If a military believes that it is in a situation that requires speedy changes, it should adopt the CAS; otherwise, it should select the PCS.

SOUTH KOREA’S DEFENSE REFORM 2020

>

BEGINNING OF DEFENSE REFORM 2020

Political leaders of the Roh Moo-hyun administration rather than military leaders initiated the South Korean DR 2020 (Defense Reform 2020). South Korea’s so-called “386 Generation,” who were instrumental in getting Roh Moo-hyun elected as President of the ROK, sought for Korea to retake the Operational Control Authority from the Commander of the CFC (ROK-U.S. Combined Forces Command) and dismantle the CFC in the name of sovereignty. Reform of the military was seen as necessary to persuade the South Korean people that the ROK military is strong enough to defend the nation without the direct help of the U.S. military.1

In early 2003, the first defense minister of the Roh administration, Cho Young- gil, started his reform initiative to “adapt to the changed security environment and potential types of future war” (Ministry of National Defense 2006b, 36). However, a year after his appointment, the defense minister was replaced by the then defense advisor to President Roh. The political leadership of the Roh administration thought that both Minister Cho’s reform plan and execution of it were not ambitious or proactive enough (Kwon 2013).

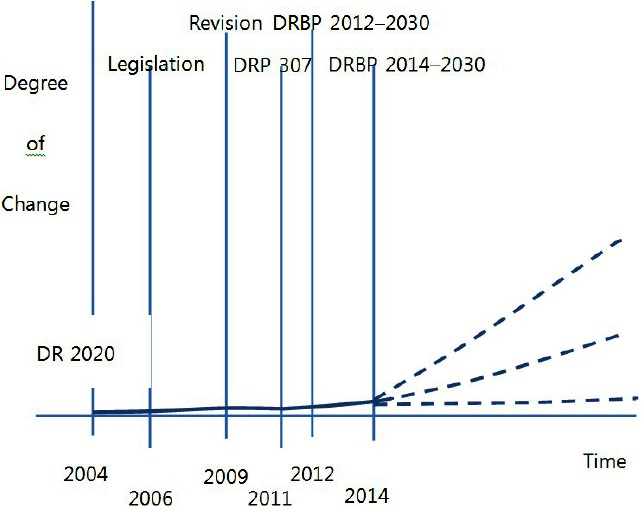

After taking office in 2004, the newly appointed defense minister, Yoon Gwang-ung, emphasized the urgent need to reform the entire defense sector. Yoon organized a small and exclusive team to formulate an initial concept for the reform. Subsequently, he organized the Defense Reform Committee in the Ministry of National Defense (MND) in June 2005 and ordered it to turn the basic concept into a comprehensive and detailed plan for the long-term reform of South Korean military. The committee followed the minister’s order, naming the plan DR 2020 and reported the plan to President Roh in September 2005. After taking office in 2004, the newly appointed defense minister, Yoon Gwang-ung, emphasized the urgent need to reform the entire defense sector. Yoon organized a small and exclusive team to formulate an initial concept for the reform. Subsequently, he organized the Defense Reform Committee in the Ministry of National Defense (MND) in June 2005 and ordered it to turn the basic concept into a comprehensive and detailed plan for the long-term reform of South Korean military. The committee followed the minister’s order, naming the plan DR 2020 and reported the plan to President Roh in September 2005. After receiving the president’s approval, the committee started to draft the defense reform bill in order to ensure long-term and continuous implementation regardless of changes in administrations or defense leaders. However, members of the National Assembly discussed the bill for almost a year before ratifying it as law in December 2006. Unfortunately, Minister Yoon had to resign about a week before the passing of the law in the wake of a shooting incident that occurred the previous year at a guidepost in the border area.

“The Law on Defense Reform” mandates that the South Korean military achieve the following goals: (1) transform the manpower-intensive force structure to a technology-intensive one; (2) transform the defense ministry from a military-led organization to a civilian-led one; (3) strengthen the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) so that they can effectively conduct modern joint warfare; (4) secure the necessary defense budget for successful reform during the fifteen-year period ahead; and (5) balance South Korea’s self-reliant defense policy with its alliance with the United States (National Defense Reform Act 2006).

Based on the law, the Ministry of National Defense of the ROK (MND) announced a plan to reduce military manpower from 680,000 troops to 500,000 by 2020 (the 522,000 target level of the current administration’s reform plan is less ambitious that this), while streamlining the army’s command structure (the same corps-centered structure as the current administration’s). It promised to increase the proportion of civilian officials among the entire workforce of the MND and noncommissioned officers in the field units. It emphasized strengthening the JCS to ensure more effective joint operations. It estimated the whole defense budget available until the year 2020 to be 621 trillion won (about 621 billion US dollars), based on the assumption of a 7% annual growth in the Gross Domestic Product on average during the period. The law mandated the preparation for retaking the wartime operational control authority over South Korean forces from the Commander of the CFC to JSC in 2012 (Ministry of National Defense 2006b). It was to build “qualitative modernized forces resting on advanced technology rather than a force whose strength is measured by the number of soldiers” (Nam 2007, 186).

The Law on Defense Reform turned out to be less effective than expected. The implementation schedule stipulated in the law was not as speedy as a reform dictated. Most of the fundamental changes, including the meaningful cut in military personnel and the creation of a unified ground operations command, were planned to take place at the last part of the reform period, near the target year of 2020. Thus, the passage of the law did not lead to any immediate results.

At the same time, Minister Yoon’s replacement, Kim Jang-soo, did not emphasize the speedy implementation of the plan as Minister Yoon might have. One could characterize his term as a transitional period to the next administration due to the planned presidential election just a year later in December 2007. He apparently decided to hand over the implementation of DR 2020 to the next administration.

The successor Lee Myung-bak administration, which was inaugurated in February 2008, rested on the strong support of the South Korean conservatives, who did not agree on the key elements of DR 2020. In particular, the Lee administration held quite a different ideology from its predecessor, the Roh administration, regarding North Korea and the ROK-U.S. alliance. The Lee government regarded the force reduction and taking OPCON authority back from the CFC as risky initiatives. Therefore, the Lee administration came to review the whole contents of the plan in a fundamental manner. It ordered the Office of Defense Reform in the MND to do report a “less risky” revised plan. In fact, President Lee was not much interested in defense reform. The first minister of defense of the Lee administration, Lee Sang-hee, was more interested in the military’s preparedness against immediate provocations of North Korea than future reform, as demonstrated by his slogan, “Fight Tonight” (Kwon 2013, 250–252). Furthermore, there was not much interaction between the presidential office and the MND on the defense reform plan. As a result, Defense Minister Lee used the excuse of there being a limited defense budget to reduce the scope of reform and the speed of change.

Minister Lee announced a revised version of DR 2020 in June 2009 after spending fourteen months to review the original plan. The revised version corrected the defense budget estimate from 621 trillion won to 599 trillion won. It increased the target number of force reduction from 500,000 to 517,000 in 2020, added a few new projects including the establishment of standing peacekeeping forces, and postponed several expensive projects including acquisition of the high-altitude unmanned reconnaissance aircraft and refueling aircraft (Park 2009). The roadmap for implementation was also delayed accordingly.

>

THE IMPACT OF THE CHEONAN AND YEONPYEONG INCIDENTS

Two North Korean provocations in 2010 seriously affected the implementation of the revised version of DR 2020. North Korea attacked and sank the South Korean navy corvette

The other North Korean provocation, a blatant attack on South Korean territory, Yeonpyeong Island, with artillery and rockets, occurred on November 23, 2010, just eight months after the

The newly appointed South Korean Defense Minister, Kim Kwan-jin, could not simply follow the recommendations of the special committee. He was advised that the creation of a Joint Operations Commander might become controversial in terms of constitutionality. Some argued that creating this new position—which would be lower than the Chairman of the JCS but higher than the service chiefs and not in the list of key military posts, which should be approved by the Cabinet Council for the appointment—might infringe the Constitution. The controversy itself would stop the implementation of the recommendation made by the special committee. Therefore, the minister asked for additional review and had to spend a few months before making his decision.

Defense Minister Kim came up with his own plan to reorganize the higher command structure instead of creating the Joint Operations Command. He decided to give service chiefs more authority such as authority on the employment and operation of the military forces in addition to their original authority for force management. He reported his own reform plan to the president on March 7, 2011, naming it after the date of its reporting (“DRP 307”). The plan was released the next day. He promised to complete the implementation of 37 short-term projects by the end of 2012, 20 mid-term projects by the end of 2015, and 16 long-term projects by the end of 2030.

Defense Minister Kim emphasized the reorganization of the higher command structure as the number one priority. In late May 2011, he requested the National Assembly to revise the related laws for the reorganization. He wanted to revise the laws in 2011, implement the reorganization in 2012, change the reorganizations of subordinate commands accordingly in 2013 and 2014, and complete the whole reorganization in 2015 (Ministry of National Defense 2011).

However, Minister Kim’s initiative, especially the reorganization of the higher command structure, met with strong opposition from retired generals, especially retired air force and navy generals. They accused the reorganization of giving too much power to the JCS Chairman, who would mostly be an army general. The opposition party lawmakers and a few ruling party lawmakers, most of them of a military background, bought the accusation and decided not to support the minister’s plan. Despite the all-out efforts by Minister Kim and MND officials, they failed to persuade the National Assembly. During the process of trying to persuading the National Assembly, precious time for the implementation of DRP 307 was wasted. The MND’s request was finally discarded at the end of the 18th National Assembly’s term in May 2012, leaving the MND in total frustration.

Because of the failure to reorganize the higher command structure, DRP 307 could not maintain the momentum. Instead of implementing other projects in the plan, Minister Kim and the MND decided to make another more detailed reform plan targeting the year 2030, which meant ten years’ postponement of the reform completion. They named the new plan “Defense Reform Basic Plan (DRBP) ’11– ’30” and adjusted (to be specific, postponed) the reform schedules to a maximum of ten years.

The name of DR “2020” became inappropriate because of the extension of the target year from 2020 to 2030. However, MND did not use the term “DR 2030” and only stopped using the term DR 2020. At the same time, MND started to update the defense reform plan annually and replaced DRBP ’11–’30 with DRBP ’12–’30 on August 29, 2012. Since then, DR 2020 seemed to have turned into a long-term “development” plan instead of “reform” plan. DRBP ’11–’30 or DRBP ’12–’30 did not have any impact on the ongoing defense activities, because the Lee Myung-bak administration was scheduled to be replaced in February 2013. These plans served as references for the defense reform of the current Park Geunhye administration, which spent a little more than a year and released its own plan, DRBP ’14–’30, in March 2014. Hence, the de facto termination of the DR 2020 occurred during the Lee administration, especially after the introduction of DRP 307 in March 2011. DRBP ’11–’30 and DRBP ’12–’30 existed only on paper, and DRBP ’14–’30 does not include new or ambitious reform projects.

1For discussion on the initiation of the defense reform by political leaders in the Roh administration and the resistance from the South Korean military, see Kwon (2013).

ANALYSIS OF DEFENSE REFORM 2020

The MND’s biennial National Defense White Papers issued in 2006, 2008, and 2010 did not mention any achievements or assessment of South Korean defense reform efforts (Ministry of National Defense 2012, 117). The MND enumerates some achievements regarding the defense reform it made between the year 2010 and 2012 in

There was no objective assessment by researchers or scholars outside the MND of DR 2020’s achievements, either. However, many criticisms were raised when the Lee Myung-bak administration took office and attempted to review the original DR 2020 (North East Asia Peace Forum/Korean Defense and Security Forum 2008; Lee 2009). Even during the review, the Lee Myung-bak administration did not pay much attention to the achievements of the DR 2020, but discussed the relevance of the reform plan, which was made by the preceding administration. DR 2020 appeared to have existed more as a plan for discussion than as a plan for implementation.

At this point, I roughly evaluate the achievements of DR 2020 based on its key foci, which were stipulated in the Law on Defense Reform. To begin, the South Korean military did not achieve any significant changes regarding the key goals of DR 2020 such as “transforming the manpower-intensive force structure to a technology-intensive one,” “transforming MND to a civilian-led one,” “strengthening the JSC,” “securing the necessary defense budget,” or “increasing the self-reliance.” It even failed to increase the civilian workforce in the MND close to the target level and was reprimanded for its poor achievements by the Ministry of Public Administration and Security in 2010 (Hankook Ilbo 2010). It is not that much of a stretch to conclude that the MND failed to make any reformlevel changes other than natural improvements that could have been achieved without any reform initiative.

The reform strategy adopted by the MND exemplifies the characteristics of the PCS. DR 2020 intended to accomplish its goals over 15 years through controlled and incremental changes, and the MND itself announced that it would pursue the reform “in a gradual and step-by-step manner” (Ministry of National Defense 2005, 9). The roadmap for DR 2020 also demonstrated that the MND planned to pursue the reform by the PCS. The roadmap divided the reform into three stages. Its first stage was to complete the beginning of the reform by 2010, the second stage was to deepen the reform by 2015, and the third stage was to complete the reform by 2020 (Ministry of National Defense 2006a). The MND wanted to make perfect preparations and increase the speed of implementation in a gradual manner as clearly described in the PCS.

The frequent replacement of defense ministers forced the MND to spend more time in planning before doing any real implementation and forced it to adopt the PCS. Defense Minister Yoon, who initiated DR 2020, was replaced by Kim Jang-soo in November 2006, just before the passage of the Defense Reform Act. Minister Kim served just over a year and he could not pursue speedy implementation of the plan because of the imminent election of the next administration in December 2007. The first Defense Minister of the Lee Myung- bak administration, Lee Sang-hee, took more than a year to review the plan and was replaced by Kim Tae-young just after the release of the revised version of DR 2020 in June 2009. Minister Kim Tae-young’s term was interrupted by the bombardment of Yeonpyeong Island in November 2010, after just over a year in service. In a span of less than five years, five South Korean Defense Ministers handled DR 2020—that is, since the passage of the legislation in December 2006 until the introduction of DRP 307 in March 2011, a total of 51 months.

During those 51 months, the MND spent about 30 months to review and revise the existing plan: 18 months from the presidential election in December 2007 to the release of the revised version of DR 2020 in June 2009, and 12 months from the

Moreover, the South Korean defense ministers and MND officials did not seem to recognize clearly the pitfalls of the PCS. They appeared to think that the slow pace of change would be very natural for peacetime defense reform. They did not express much concern that the slow pace of implementation could result in cancellation or interruption of the reform plan at any point until the year 2020. They seemed to think that the review of previous plans by a new defense minister or administration would be quite natural and did not worry much about the waste of time for the implementation. This is why they delayed the target time from the year 2020 to the year 2030 without any apology or explanation to the South Korean public.

The case of the South Korean DR 2020 demonstrates the typical problems that the PCS can bring when attempting reform. Despite strong support from President Roh and the strong will of Defense Minister Yoon, who were the driving forces behind the initiation of DR 2020, DR 2020 ended up wasting its initial golden time in making a perfect plan. If Defense Minister Yoon had employed the CAS and pursued immediate across-the-board changes to the military, he would have achieved bigger reformative outcomes by taking full advantage of his political power during his relatively longer term.

However, the adoption of the CAS should not be equated with success of the South Korean defense reform. Other important factors could have affected the outcome of the reform as well. For example, the budget constraints limited the scope and speed of the reform regarding the South Korean defense reform (Klingner 2011; No 2012). The actual annual increase of the defense budget during the Roh Moo-hyun administration was about 8.8% on average in contrast to the 9.8% request. The Lee Myung-bak administration provided only a 5.2% annual increase of defense budget, although it had promised an increase of 7.6%. This gap in the defense budget functioned as the main reason why MND had to revise the plan repeatedly. By 2010, Defense Reform 2020 already had a 42 trillion won shortfall, causing the MND to admit that it was unable to achieve the initial goals of the defense reform (Klingner 2011). However, if the ROK military had reset the priority and increased the efficiency throughout all fields of the military, it could have minimized the budget constraints to the reform. As Stephen P. Rosen cautioned, “it is wrong to focus on budgets when trying to understand or promote innovation” (1991, 42).

The resistance from members of the military including the higher rank generals may have affected the delay of South Korean defense reform. Although the MND had promised to reduce the strength of total forces to 500,000 from 680,000 in 2005 including the 15% reduction of number of generals until the year 2020, it continuously adjusted the target strength and delayed the schedule of the reduction. However, because South Korean armed forces have been led dominantly by the army generals of graduates of the Korea Military Academy, there could not be much room for bureaucratic struggle among various interest groups compared to what one sees regarding U.S. armed forces (Zakheim 2007). On the contrary, more of the blame should be placed on the defense ministers’ lack of passion for defense reform than on the ordinary South Korean officers in the military bureaucracy.

The pressures and top-down directions by political leaders may have distorted the implementation strategy of the MND. For example, the political leaders in the Kim Dae-jung and Roh Moo-hyun administrations demanded the ROK military to reduce the strength of its forces based on these presidents’ optimistic perception of the North Korean threat (Kwon 2013). At the same time, they forced the military to retake the OPCON authority from the CFC (Kwon 2013), even though the military was not ready to do so. However, these two political decisions could have been used as a strong political support for the defense reform, if South Korean military leaders were wise enough to take advantage of the political will to reform the military. Eventually, these decisions were reversed at the beginning of the Park Geun-hye administration.

Researchers might identify these factors mentioned above as the main culprits for the failure of the South Korean defense reform. However, these factors might not be insurmountable ones regarding the defense reform. They might be key considerations in selection and shaping of the right strategy. A reformist leader should and could come up with creative solutions to handle these factors appropriately and minimize the negative affect to the reform. If South Korean defense ministers had had strong determination for the successive implementation of defense reform promises and selected the right strategy to overcome the negative affect of these factors, only little room would have been left for these factors to hamper their reform efforts. The strategy is to develop the best “ways” and mobilize the most “means” to overcome obstacles or harsh environment in order to reach the “ends” in mind.

LESSONS FROM SOUTH KOREA DEFENSE REFORM 2020

>

ADOPT THE CHANGE AND ADJUST STRATEGY

Most of all, the South Korean military should recognize the importance of the implementation strategy it adopts for its defense reform. The case of DR 2020 clearly demonstrates the fate of a reform that uses a wrong strategy. The South Korean military should recognize the downside of the conventional strategy it has adopted in most of its reform initiatives, and try to set the appropriate reform strategy in addition to the contents of defense reform.

The South Korean military may need to adopt the CAS focusing on producing immediate results. It had already developed several comprehensive and detailed plans for long-term defense reform such as DR 2020, DRP 307, DRBP ’11–’30, DRBP ’12–’30, and DRBP ’14–’30. It should focus on clearing the backlogs of the previous reform plans instead of waiting for the planned execution schedules of the DRBP ’14–’30, which was released in March 2014.

The DRBP ’14–’30 needs to be implemented without any further fundamental adjustments for the coming years. Some projects in that plan need to be expedited. The military leaders should do their best to identify problems such as budget limitations with regard to the implementation of the plan and find solutions in order to ensure the implementation. For the time being, they should be the commanders on site for the timely implementation of the plan. Instead of providing “vision of distant future capabilities,” they should focus on the “solution of specific immediate problems” (Knox and Murray 2001, 185).

>

REDUCE PLANNING TIME FOR SPEEDY IMPLEMENTATION

The South Korean military should try to reduce the planning time in its reform efforts. It should recognize the opportunity cost it would incur by delaying implementation for the sake of perfect planning. If the South Korean military recognizes the seriousness of the North Korean nuclear threat, it cannot have the luxury to spend much time on planning. The South Korean military needs to make the most of the existing plans and avoid fanfare announcements.

The South Korean military leaders should try to make decisions faster. They should delegate appropriate authority to their subordinates so that they can focus on key issues. They should begin the reform with selected projects, which could be done within their given authority or term. Since South Korean defense ministers serve for an average of 16 months,2 it is almost impossible for any minister to implement multiple projects in his term. Because the South Korean military has too long a backlog, military leaders can find sufficient projects for reform that can be done under their authority and during their terms.

In order not to be stuck in the planning period, the South Korean military should depart from its previous reform focus—that is, the structural change of the military. As clearly demonstrated by the case of DR 2020, structural reform requires too much time for review, discussion, and planning. It also needs additional time for building consensus among members of the military. Structural reform mostly requires the revision of laws, which may take years. Since the previous South Korean defense reform initiatives focused on structural reform, it might be an appropriate time to move the reform focus to the operation and management sides of the military. This approach can increase the participation of all members in the reform, build consensus more easily, and produce immediate improvements.

>

CONNECT THE PLAN TO THE IMPLEMENTATION THROUGH FEASIBILITY ANALYSIS

If the South Korean military wants to heighten the rate of implementation of its reform efforts, it needs to increase feasibility of the reform projects. DR 2020 clearly demonstrated the loopholes of an optimistic plan that turned out to be based on the wrong calculation of available budget. DRBP ’14–’30, release in March 2014, assumed that 7.2% annual increase of the defense budget would be possible between the year 2014 and the year 2030. However, the actual defense budget growth for the year 2014 was only 3.7%. Without an accurate calculation of the available defense budget, no reform project can be implemented as promised. The reform plan would go through another revision process to adjust to the reduced defense budget and could repeat the same mistakes of DR 2020.

For this reason, the South Korean military should start its reform by increasing efficiency across the board. It must minimize waste and redundancy in order to allocate more money for reform projects without decreasing the military’s readiness level. Sometimes, the military should be able to cancel several less necessary projects in order to ensure the necessary budget for indispensable or urgent projects. It should perform an analysis of cost-effectiveness of reform projects before it decides the investment. The increase in the efficiency of the military would be a key ingredient of contemporary defense reform and a foundation for the success of key reform projects.

Another urgent, quickly implementable and mostly budget-free reform area for the South Korean military would be the improvement of unreasonable regulations, custom, and culture in the military. These were neglected in the previous reform initiatives. However, these are the roots of problems for the South Korean military. “Loss of focus on cultural change . . . will undo whatever programmatic progress is made in matters of acquisition, training, logistics and operations” (Zakheim 2007, 28).

To be specific, how can the South Korean military become an advanced military under current personnel systems, which rotate officers in a year or two? How can it encourage all military members to participate in the reform efforts with its current strict top-down and one-way communication culture? The leaders of the South Korean military should start to make most regulations, custom, and culture more reasonable and productive. These changes can be done without any intervention or financial support by the government and the National Assembly.

>

ESTABLISH OVERSIGHT MECHANISMS FOR THE IMPLEMENTATION AS PLANNED

Most of all, the presidential office and the National Assembly should check whether the South Korean military is implementing its reform plans as it promised. They should ask the MND to report the progress regularly and demand explanation if there is a discrepancy between the executed results and planned projects. The president or the National Assembly can make a special team composed of independent civilian experts to oversee the execution of the reform plans of the MND and to provide necessary supports for the success of defense reform.

The South Korean military also should recognize the importance of evaluating the degree and quality of the implementation of its reform plans and create its own team for the job. The Office of Defense Reform in the MND should focus on this job instead of simply making another plan. The office, on behalf of the defense minister, should ask the respective services, agencies, and units for roadmaps for their own reforms. Through objective and persistent oversight, South Korea can prevent the repeated production of overoptimistic military reform plans. It should make officials accountable for their failure or success in the reform efforts. Without active oversight of the implementation, plans of the defense reform will look good on paper but never come to complete fruition (Zakheim 2007).

The South Korean people may need to monitor actively the status and achievements of their military’s reform efforts as well. The public can demand regular release of the concept, strategy, direction, contents, and roadmaps for the reform and provide feedback if necessary. In particular, as representatives of the people, the National Assembly members should ascertain the details of defense reform projects, closely monitor their progress, and sometimes stimulate the fast implementation. Members can take a leading role by holding various types of discussions regarding defense reform issues and reconcile the plan with the reality. They should support or stop reform projects through the prudent allocation of budgets.

2Twenty-three Defense Ministers served for 30 years (360 months) since 1983, when the system of five-year terms for the administration started. In sum, 360 months divided by 23 Defense Ministers equals 15.6 months per Defense Minister.

It would be very difficult to evaluate any military’s reform efforts as successful or unsuccessful unless the military was tested in a war. As the amount of sold merchandise decides the ability of the salesperson in the market, the victory in war would be the only indicator of the success of the reform. If a particular military won the war, the reform conducted before the war should be evaluated as successful. As the acquisition time for military equipment is long, the result of a certain defense reform initiative would emerge far in the future.

However, a gradual approach in making changes tends to delay or hinder urgently needed reforms. Reform projects could be stalled midway through the change for various reasons such as leadership change, economic downturn, unexpected incidents, and so forth. If a particular military is too hesitant in making changes, it would create a capability gap with an adversary that is more proactive. A military could use the gradual approach—identified in this study as Plan and Change Strategy (PCS)—as an excuse not to make any changes until the real-world situation dictates. Therefore, one could apply the change first strategy—i.e., Change and Adjust Strategy (CAS)—especially when reform becomes very urgent.

The South Korean military appeared to adopt the PCS and, before one plan replaced another, failed to achieve the planned results. It spent too much time in planning and allowed interruption in the middle of implementation. Although Defense Minister Yoon ensured the continuation of DR 2020 until the year 2020 by passing a law, the law could not defend DR 2020. DR 2020 was revised by change of administrations, threatened by the

The incumbent Park Geun-hye administration should learn the lessons evident from the failure of DR 2020 and adopt a different strategy. The government should expedite the implementation of the plan it announced in March 2014 instead of updating the plan next year. If it adopts the same PCS for its defense reform, it will repeat the same mistakes as the previous administrations.

The South Korean military should take every measure to increase the speed of implementation. It should focus on some key projects for immediate implementation rather than annually updating the plan. It should select only a few urgent projects and allocate more time and resources on them. The leaders of the South Korean military should try to make decisions faster in order not to waste time. “The cost of failure to change now will be a far higher price in lives and treasure to be paid” (Knox and Murray 2001, 194). Because of the importance of the budget in this capitalist society, the South Korean military should start its reform initiative by increasing efficiency across the board. It must minimize waste and redundancy and save the money in order to concentrate on more important projects. It needs to urge all military members to increase efficiency in their offices and work. When the military does its best to spend the given budget wisely, the National Assembly should respond by allocating more money for fast defense reform.

Another urgent measure for successful defense reform is establishing an oversight mechanism on the progress or result of the reform. The South Korean government and/or the National Assembly should recognize the necessity of an objective and persistent oversight on the implementation of the defense reform. If the assembly seeks a more objective assessment, it can ask an independent and civilian organization to conduct one.

Beginning defense reform may not be that difficult. However, completing it with productive achievements is quite difficult. Any leader who wants to achieve a successful reform should make every effort to implement the reform plan with a proper strategy.