The aim of this paper is to focus on the issue of the labor rights of migrant workers in Taiwan. First, a general profile of the unskilled migrant workers in Taiwan will be provided. This will be followed by a brief review of previous studies on migrant workers, in which it will be argued that the current research on migrant workers in Taiwan has mainly focused on domestic caretaker and gender issues. While some studies have looked at overseas investment by Taiwanese businesses and related labor relations, little attention has been paid to the structure of the relations set by the state in which the human rights issues of the migrant workers have been framed in Taiwan. It is argued in this paper that the social relations of migrant workers are key to the human rights issues which have been shaped by the developmental state. The productive relations of the migrant workers have been derived from the empirical research that shows how the conditions facing migrant workers have been shaped by the structure of economic relations in which migrant workers have been perceived as material resources under the fixed nature of employment relations. Unlike those workers who are free to move within the market, these migrant workers can not move in this way and should certainly remain loyal to one employer in accordance with the state rules that have been drawn up for migrant workers.

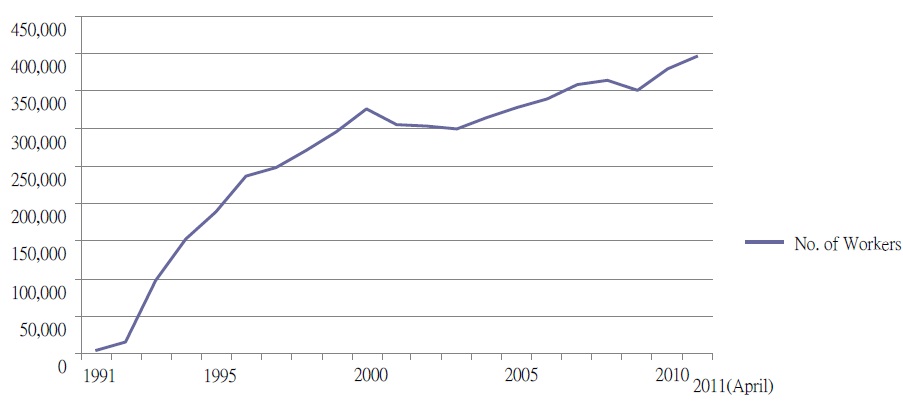

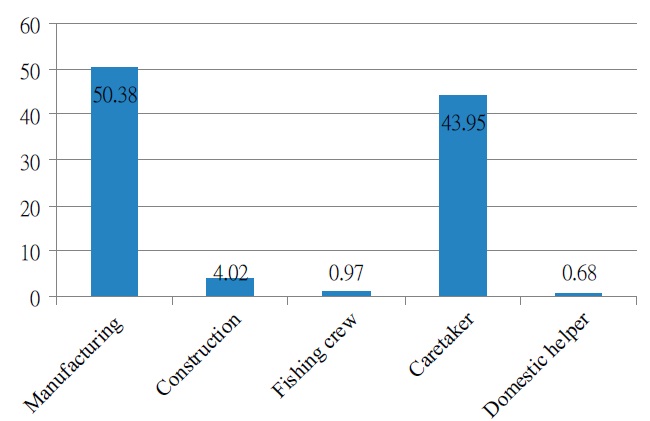

In 1992, the authorities in Taiwan began to admit foreign blue collar workers to work in specific job categories in Taiwan (Lee 2008). Figure 1 reveals the changes in the total number of migrant workers in Taiwan from 1991 to 2011. It shows that the number of workers increased dramatically beginning in 1991. At the time of writing (2011), there are about 400,000 migrant workers currently employed in Taiwan which is about 4 percent of the total employed population in Taiwan. Although this may not be a significant number when compared with the total employed population, it has formed a significant part of the current blue collar employment population in Taiwan as the government has sought to supply migrant workers to make up for the labor shortage at the low end of the labor market. These blue collar migrant workers are mainly imported to fill unskilled positions of blue collar workers in manufacturing, caregiving and the construction industry (Figure 2). In 2009, migrant workers in total accounted for just over 10 percent of the overall blue collar labor force in the country. Migrant workers in Taiwan come from Southeast Asian countries such as Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam. These countries have been the main sources of migrant workers in Taiwan.

According to the Council of Labor Affairs (CLA), the purpose behind introducing migrant workers to Taiwan is for them to serve as a supplementary labor force to fill the gap in terms of the labor shortage among mostly unskilled, dangerous and low-paid professions. The objectives in importing migrant workers are as follows:

It has been estimated that in recent years there has been a shortage of labor in the low-end employment market. Between 1990 and 2008, the share of blue collar workers in the total employed population declined from 36% to 31%. Although a significant number of foreign blue collar migrants are now working in Taiwan, in academic research little attention has in general been paid to their working conditions and their life in public.

There are various studies that have contributed to the labor rights issues of the migrant workers (Chan 1998; Battistella 1993). There is also research that has focused on NGOs in supporting the migrant workers in various countries (Ford 2004). In Taiwan, however, migrant labor has been studied from a different perspective.

For example, there is research that focuses on domestic workers in terms of gender issues (Lan 2003). Cheng (1996) also examines the situation regarding foreign and domestic female workers in terms of the state governance of foreign workers; it has also been shown that in the analysis of cross-border care work, especially in relation to domestic workers, the state is still in the central place in the analysis. In comparing the legal systems of Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan with regard to migrant workers, Cheng (1996) has concluded that Taiwan is similar to Singapore in that it lacks sufficient legal and social support for migrant women. By adopting a rather different approach, Lee and Wang have focused on analyzing policies to control migrant workers as a means to improving the state’s efficient control of illegal migration (Lee and Wang 1996).

Nevertheless, current research has paid little attention to the labor rights issues of the migrant workers in Taiwan. In particular, there are few studies that focus on the labor issues of migrant workers in the manufacturing industry in Taiwan. Recently, Chan and Wang (2004) compared the role of state intervention in labor management in Taiwanese-invested factories in China and Vietnam, and found that there is a clear difference in terms of the management of workers between the two countries. Workers in Taiwaneseinvested factories in Vietnam are given better treatment and enjoy certain labor rights such as the right to organize strikes at the work place, which is unusual in Taiwanese-invested factories in China. With the certainty of state involvement in supporting labor rights, workers in Vietnam are aware of the labor law through government regulations along with trade union involvement. It is quite clear that the state can take action to protect its own citizens from human rights abuses by foreign investors. However, the way a state like Taiwan treats foreign labor and deals with labor rights issues is quite different and little empirical research has been conducted in this field.

Recently, there has been a lot of discussion on the developmental state with specific reference to countries in Far East Asia (Weiss 2000; Pempel 1999). The state has played an important role in economic development in Taiwan (Amsden 1985). Differing from the western liberal state, Dicken (1998) shows how the developmental state performs as an external regulator of the market while playing a highly interventionist role in market economies. As Leftwich suggests, there are six features of the developmental state (Leftwich 1995): (1) a determined development elite; (2) the relative autonomy of the elites and the state institutions which they command; (3) a powerful, competent and insulated economic bureaucracy; (4) a weak and subordinated civil society; (5) the effective management of non-state economic interests, for example where the state may control national or foreign capital; and (6) the combination of the occasional brutal suppression of civil rights, the widespread support of legitimacy, and economic performance as the state makes rational plans in promoting economic growth. Although there are studies on the role of the developmental state in partnership with economic agents in economic growth, less attention has been paid to how the concept of a developmental state can be used to analyze the labor rights issues of migrant workers. Thus, it is the main purpose of this paper to contribute to the discussion on the developmental state in terms of labor rights, and more specifically the labor rights of foreign workers. The main research question this paper should answer is: How can the concept of the developmental state be used to shed light on the labor rights issues of migrant workers?

The social relations of migrant workers are critical to the human rights issues that surround them. According to the laws enacted by the government, low-end migrant workers are allowed to work for certain industries under certain conditions as set by government regulations. For instance, the employers should provide a management plan and services in regard to accommodation, food, accident insurance and medical insurance, and which hiring agents’ services are needed. Furthermore, the contracts between the workers and their employers should be legalized before the migrant workers apply for a visa to enter Taiwan. Documents, application procedures and seeking workers overseas has made the hiring agents a critical medium between the demand for and supply of labor.

On the labor demand side, the hiring agents provide and promote the importing workers service for the employers. On behalf of the employers, the agents apply for government permission to import workers from abroad. When such permission has been granted, the agents will recruit the workers from the home country of the migrant workers by linking up with local agents in the foreign countries. Unlike those workers who act freely in the market, these migrant workers rely on agents to obtain the information regarding job opportunities in Taiwan. As there is a strong demand to work in Taiwan, the terms of the employment contract are fixed by the demand side.

The migrant workers find the job opportunities via local recruitment agencies in their home country. First of all, an interview with the agent on behalf of the employer in Taiwan will decide whether the applicant is suitable for the job. When this hurdle has been passed, the applicant will sign the contract with the agent. The applicant will then need to pay a commission to the home country agent, which is about two months’ salary for working in Taiwan for a one-year contract. In addition, the migrant worker also needs to pay one month’s salary in installments over the one-year contractual period to the Taiwan agent, which will be deducted from the monthly salary. For those migrant workers with a three-year contract, the commission for a three-year contract to be paid to the local agent will be much higher and up to 120,000 Philippine pesos, or about NT$ 82,488, equal to roughly 5 times the basic monthly salary for working in Taiwan. Most workers that I interviewed paid the commission fee by borrowing from the lending companies in the Philippines at a high interest rate using the employment contract as collateral. Even though the total commission fee is high, foreign workers would still like to pay to work in Taiwan. As one interviewee said: “No money, no job! There are plenty of people in the Philippines seeking to work overseas.”

The contract contains the length of the contract, the working hours, pay, vacations, insurance, etc. The wage is fixed at NT$ 17,280 per month for all the migrant workers who work as manufacturing workers in factories and it just meets the minimum wage (NT$ 17,280) for labor according to Taiwan’s labor law – the Labor Standards Law. As is clearly stated in the employment contract for the migrant workers, all conditions for migrant workers should comply with the law. The minimum number of working hours is 8 hours per day and 84 hours over a two-week period. Payment for overtime and the maximum amount of overtime should also be regulated by the law. The employer also needs to provide food and accommodation for migrant workers for which payments can be deducted each month from the workers’ salary. Migrant workers should live in the accommodation provided by the employer and the employer can charge a lodging fee of up to NT$ 4,000 a month.

Several distinctive characteristics of the social relations of migrant workers have been clearly revealed and are closely related to the migrant workers’ human rights issues. First, the developmental state initiates and acts as a middleman to help and solve the problem of production for the industry. Second, the working conditions of migrant workers are highly regulated by the state. Unlike the domestic workers in the market who may move from one job to another, the migrant workers, in accordance with the objectives of government policy, do not enjoy the right to terminate the contract and move to another job.

Third, the agents involved in the hiring and management of migrant workers become an important medium in these relations. Unlike those workers who are active on their own in the market, the migrant workers are subordinate to the agents when it comes to work opportunities. When different agents are in competition with each other for recruiting migrant workers, the conditions and rights of migrant workers will be in a most vulnerable situation.

From the above analysis, the social relations of migrant workers with other agents in terms of productive relations are created by the state and made possible through the medium of hiring agents. This is certainly related to issues of human rights.

Several points regarding the vulnerable situation that migrant workers face have been revealed from interviews with migrant workers through our empirical research so far.

The monthly wage has been fixed at NT$ 17,280 per month (in 2009) for these migrant workers. It has been found that the migrant workers’ salary is much lower than that of those local coworkers who are doing same type of job. One informer said: “We are paid less but are required to do much more.” Overtime work for some migrant workers is quite a usual situation in my study. Due to the overtime payment also being lower for them than that which needs to be paid to the local workers, employers are more likely to ask migrant workers to work overtime. It is the obligation that should be obeyed by the migrant workers and this has been clearly stated in the contract. In my study, the total number of overtime hours seems to be far higher than according to the regulations. One migrant worker in my study works 10 hours per day six days a week and also needs to work on Sundays. “No rest”, he told me. 46 hours per month is the limit set by the law. Other informers also revealed that overtime is a usual situation and that the overtime payments are a big supplement to their income as they will receive about 50 percent more salary due to the income from overtime.

On the one hand, the migrant workers are willing to receive the extra income through working overtime. One interviewee said: “17 thousand a month is too little but over 22 thousand will be alright,” even though the amount received by local workers is much higher. He believes that local peer workers would be paid at least 28 thousand without working overtime. On the other hand, they also like to have more time to rest. However, it is very difficult for them not to obey the employer’s orders. It seems they have no choice but to follow the order to work overtime. More importantly, it is quite usual for no work to mean no pay. On those involuntary holidays ordered by the employers, the migrant workers will not be paid because there is no work, which is not stipulated in the contract. According to my study, a particular migrant worker will not get paid when the boss is dissatisfied with his performance and tells him not to work.

Migrant workers have also suffered from verbal and physical abuse. The way management acts toward migrant workers is certainly different from that in the case of local workers. One informer complained by saying: “My boss is OK, he is a nice guy. But the supervisor always gets angry for a very trivial thing.” He swears a lot to them. He would not act the same toward the local workers. He can be angry about the same thing for a week’s time.” All the migrant worker can do is not argue with him and keep his head down. In his work place, there was one Filipino worker who did argue with the supervisor and, the next day, he lost his job and was sent back to the Philippines. “Once you are back in your country, it is very difficult for you to find an agent to look for overseas work.” There are many people looking for jobs. Apart from verbal abuse, some have revealed that it is quite common for migrant workers to not be immune from physical insults. It is quite often the case that the supervisors will hit the workers when they have lost their temper and are dissatisfied with the workers’ performance. However, verbal and physical abuse seems to be less likely to occur in the case of the local workers.

The limited rights of migrant workers are closely related to the social relations set by the employment relations between the employers and migrant workers. Unlike local labor that can move freely in the labor market, migrant workers have no such right to move between different employers in Taiwan. The regulation of migrant workers has meant that migrant workers are unable to change their employer. Although there are some rare cases where migrant workers can move between different employers, such moves always have to be made through the hiring agent which is certainly not based on the will of the migrant workers. More often than not, it is done due to the requirements imposed by the employers on the hiring agents.

The employment relations become fixed when the employee signs the job contract before entering Taiwan. This fixed relationship puts the migrant workers in a much weaker bargaining position. The hiring relationship can certainly be terminated by the migrant worker during the first month of working in Taiwan, as it has been stipulated in the contract. However, the migrant workers are only entitled to a refund of 50 percent of the commission payment. In addition, when the contract has been terminated, the reason for staying in Taiwan will also have been terminated and the migrant workers should return to their home country. This seems to be very critical to the labor rights of migrant workers. All the workers have to accept the practical situation and to be subordinated to the same boss during their stay in Taiwan.

All the interviewees in this study are manual workers working in marble factories. Before they started the job, the employers and the hiring agents did not provide any training to the workers. They learned on site from coworkers and the supervisors by sign language. There has been a government regulation requiring that the employers should have a language translator on the job site for those large factories with acertain amount of migrant workersl, but because all of the interviewees worked in small businesses, it has not been against the law to not have a translator.

The condition of the accommodation provided by the employers varies, although the government has set guidelines for accommodation. One interviewee said that the room was very small and about the size of two single beds. Usually, they share with others. In my study, it has been found that six workers share a small room in which small bunks with only 150cm high are those migrant workers personal space for sleep.

There was no privacy and fights among workers usually happen. The accommodation is not for free. Migrant workers needed to pay for the rent and food which amounted to NT$ 4,000 monthly (about 25 percent of the basic monthly salary) to the employer, as stipulated in the contract.

>

No participation in trade unions

Although they could join the local trade union just like the Taiwanese workers, they seldom did so. It was not because they could not be well connected to the local Taiwanese trade union due to the language barrier, but was, as I would argue, because the migrant workers’ special employment relations are different from those of local Taiwanese workers. It has usually been considered that there are different and sometimes contradictory interests between local and migrant workers. For example, migrant workers have been perceived of as being replacements for domestic workers, which is a threat to local workers and the basis of the trade union. Thus, NGOs such as religious organizations tend to become the main form of support for migrant workers. While a legal aid service is now promoted by the Council of Labor Affairs and several telephone hotlines have been provided since 2000, nevertheless, these are less known to the migrant worker. As it has been revealed in a 2008 human rights report by the US government, “the CLA did not effectively enforce workplace laws and regulations,” as the workplace inspection rate was too low to deter legal violations (Department of State 2009).

The above analysis clearly shows the nature of “rational planning” by the developmental state in importing migrant workers. This is not only because the state decides the number of workers and the industries to which the migrant workers can be introduced, but also because the employment relations have involved strong state intervention. The wage has been set at the minimum wage level and the employment relations have been fixed and are not changeable due to the condition for work are not made from market operation. It is illegal for the migrant workers to change their work place unless the employer is guilty of misconduct, which is certainly not decided by the migrant workers. Clearly, the migrant workers do not have the right to move freely.

It is this structure set up by the state in which the social relations of migrant workers have been arranged and the labor rights of migrant workers established. The employment contract has brought the rights of migrant workers under the control of recruitment agents and employers. Compared with local labor, migrant workers’ rights have been undermined, with the least concern by the state. Clearly, the human rights of the migrant workers will not be enforced under such a framework as they would be in the case of the local workers. What has been needed is the intervention of NGOs to safeguard the rights of migrant workers. Although there are religious institutions such as churches that provide support for the migrant workers, nevertheless, more support from NGOs is needed.

In this paper, the labor rights issues of migrant workers have been examined based on the concept of the developmental state. First, it is shown that there are increasing numbers of migrant workers employed in Taiwan and that the importation of migrant workers is governed by strict state rules. In this paper, I argue that importing migrant workers into Taiwan has been part of a state strategic plan to supplement the labor force in response to a blue collar labor shortage. The social relations set by the employment contract have forced the migrant workers to be subordinated to the control of recruitment agents and employers. Job transfers are unlikely and the salary paid is the minimum so that overtime work is necessary if they are to receive extra income for which they are exploited. These individual workers do not have the support of a trade union or other organizations which makes their position vulnerable. The intervention of NGOs in safeguarding the rights of migrant workers is thus needed.