Corruption has triggered the collapse of authoritarian regimes in a number of developing countries, notably Iran in 1979, Uganda in 1979, Thailand in 1982, Argentina in 1982, Haiti in 1985, the Philippines in 1986, Brazil in 1986, Nigeria in 1998, and Indonesia in 1998. In all these cases, regime change was followed by efforts to implement rapid democratisation, during the course of which the failure to control corruption constituted perhaps the most evident weakness of the newly democratic regimes; the very phenomenon that helped precipitate regime change became a serious challenge to the political legitimacy of the new regime. The structural reason for this failure can be put quite simply: governmental institutions in a new political order are almost inevitably weak. Overcoming this structural weakness is a complex and difficult task, and such limitations on state capacity make it crucial that civil society take an active political role. One purpose of this article is to examine the role that civil society organisations (CSOs) are required to play in combating corruption during the democratic transition.

As described at greater length below, recent studies have recognised the importance of understanding the social context that makes corruption more likely in a transitional democracy. Based on both the following literature review and on our observations of the Indonesian experience, we suggest that CSOs play an increasingly important role in policy formation and policy implementation in new democracies for two reasons. Firstly, civil society leaders had been generally key players in the struggle against corruption under the authoritarian regime, and political activists generally expect them to lead this struggle during democratic consolidation. Secondly, the failure of the state to deal adequately with this problem creates a new political space, one that is best filled by CSOs.

While it is important to establish the role of CSOs in the process of democratic consolidation, it is more difficult to accurately describe how their activities may or may not advance the anti-corruption drive. The theorisation of CSO operations is often inadequate, and the second purpose of this article is to propose a framework for describing how CSOs fight corruption. A later section of this article describes the mechanisms by which CSOs would contribute to anti-corruption efforts. We conclude by asking, what are the implications for state-society relations when CSOs assume such a role during periods of democratisation?

Key Concepts: Corruption and Accountability

Before we begin our analysis, we need to first establish some conceptual ground rules. Corruption is usually described as behaviour involving the misuse of public office or resources for private interest (Rose-Ackerman 1978; Moodie 1980; Andvig and Moene 1990, p. 11; Huther and Shah 2000, p. 1). For this investigation we employ the typology of corruption developed by Shah and Schacter (2004), who suggest three broad categories: (a) “grand corruption,” where a small number of officials steal or misuse considerable stocks of public resources; (b) “state capture” or “regulatory capture,” involving collusion between public and private agents for personal benefit; and (c) “bureaucratic” or “petty” corruption, namely the involvement of usually a large number of public officials in extorting small bribes or favours. Grand corruption and state capture is usually committed by political elites or senior government officials who design policies or legislation for their own benefit, enabling them to misuse large amounts of public revenue and/or facilities, often while taking bribes from national or transnational companies. At the other end of this scale, petty corruption is committed by ordinary civil servants when implementing government policy. It usually takes place at the point of exchange between public and civil servants offering public services such as in immigration, the police force, hospitals, taxation offices, schools, or licensing authorities (Shah and Schacter 2004, p. 41).

Regardless of its cause and form, corruption occurs whenever power holders are not subject to close social monitoring. A useful measure for the level of corruption in a particular country is the formula proposed by Klitgaard (1988, p. 75):

If an official controls access to a resource but possesses discretionary power without significant social constraint, then s/he will have more opportunity to act corruptly. By contrast, an effective accountability system ensures good governance, for a high level of accountability obliges power holders “to act in ways that are consistent with accepted standards of behaviour”; importantly, “they will be sanctioned for failure to do so” (Grant and Keohane 2005, p. 30).

Several forms of accountability need to be implemented simultaneously in order to constrain corruption: “horizontal accountability” involving viable check-and-balance mechanisms between state institutions, “vertical accountability” whereby officials are subject to elections and other forms of social monitoring, and “external accountability” entailing robust international scrutiny and support (Diamond 1999). The operation of such mechanisms will reduce corruption because it will result in the punishment of government officials who behave corruptly or are incapable of delivering good services to their citizens (Fackler and Lin 1995; Bailey and Valenzuela 1997; Rose-Ackerman 1999; Laffont and Meleu 2001). By contrast, corrupt activity— whether it is “petty,” “regulatory” or “grand” in scale—becomes more widespread if accountability is not rigidly enforced.

Of direct relevance to this study, each of our three categories of corruption is measured, each more prevalent in developing democracies than in mature democratic countries. In order to assess the effectiveness of measures to combat corruption during a period of democratisation, we therefore need to explore various explanations for its prevalence in the developing world.

Theorising Corruption and the Democratic Transition

We can identify a number of explanations commonly used to account for the high incidence of corruption in developing countries. For some, corruption is closely related to distribution of wealth: the greater the income inequality, the higher the level of corruption. It is suggested that if resources and opportunities are equally distributed, people are more likely to share with others and consider themselves part of the broad society. In a highly unequal society, on the other hand, people tend to become more protective of their own interests—and are more likely to indulge in corruption as a means to that end. In this perspective, the level of corruption in developing countries is the product of income inequality (Rothstein and Uslaner 2005, p. 52; Husted 1999, p. 342; see also Scott 1972

Other theorists suggest that corruption occurs when the elite has more opportunity to enrich itself. Countries that have legal and socio-economic systems that maximise the risk of being caught and punished are likely to have less corruption. But developing countries are often dominated politically by elites who are above the law, lessening the effectiveness of such “reward and punishment” mechanisms (Treisman 2000, p. 400). Governance is typically influenced by strongly clientelist or patrimonial cultures that have a number of common characteristics: poor legal enforcement, high degree of state intervention in private activity, extensive public employment, poor accountability mechanisms, and political authoritarianism (Heywood 1997; Adsera, Boix, and Payne 2003; Szeftel 2000).

A third explanation for the higher levels of corruption in developing countries emphasises the historical process of capital accumulation, suggesting that corruption is a form of primitive accumulation by an emerging domestic capitalist class. In developed countries the capitalist class initially secured its resources and wealth through colonialism (Hicks 2004, p. 11). But as Iyayi (1986, pp. 28-29) points out, corruption is more prevalent in developing nations because their political and business elites lack the opportunity for capital accumulation through other means. In this perspective, the high incidence of corruption reflects the fact that these countries are relative latecomers to capitalist development.

To sum up the argument thus far, it is possible to identify three common accounts for why corruption tends to be higher in developing countries: as a consequence of higher levels of economic inequality, as a reflection of the patrimonial cultures sustained by dominant political elites, or as an expression of the fact that a country is in the early stages of capitalist development. Notwithstanding such differences in factors responsible for the “ills” of corruption in developing countries, one element is often shared: the democratisation of political life is commonly prescribed as the cure.

Democratisation is defined here as the replacement of an authoritarian regime by a democratic government through the mechanism of free and fair elections (O’Donnell and Schmitter 1986; Gill 2000, pp. 8-42). It is often expected that improved governance will eliminate a range of poor practices (Cunningham 2002; Doig 2000; Johnston 2000

This optimistic scenario has not, however, been a reality for most countries of the developing world. Certainly, the most corrupt regimes are also the most authoritarian. But most of the newly democratic states swept along by the “Third Wave” of democratisation that began in the mid-1970s (Huntington 1991) indicate that they have made little improvement in handling corruption. In fact, Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI)2 indicates that the level of corruption in most newly democratic countries is not much different than it had been during their authoritarian period. In some cases the situation is even worse (Beichelt 2004; Fleischer 1997; Harriss-White and White 1996; Hope and Chikulo 2000; Nickson 1996; Seligson 2002).

If there is no necessary link between democratisation and the success of anti-corruption efforts, does this then mean that the two processes are unrelated? Clearly, authoritarian political contexts offer more opportunities for corrupt behaviour. But under what conditions does democratisation reduce corruption? And when does it simply consolidate old practices—or perhaps lead to new forms of corruption?

Before turning to the mechanisms that may link democratisation to anticorruption measures, we should be aware of the obstacles to be faced. Democratisation itself may create structural conditions that encourage corruption. For Moran (2001, pp. 378-79), all transitions to democracy tend to make corruption worse, whether it involves establishing a new nation-state during the process of decolonisation or constructing a new political order after the emergence from authoritarian rule. In their comparative study of democratisation in various countries, Rose and Shin (2001) also show that a legitimate democratic regime creates new opportunities for corruption. Similarly, the World Bank (2000, p. xix) finds that democratic transitions in Eastern Europe and in the former USSR created fertile environments for corruption, for they involved “the simultaneous transition processes of building new political and economic institutions in the midst of a massive redistribution of state assets.”

In addition to such institutional uncertainties, the socio-political instability associated with the democratic transition creates fertile fields for corruption (Rose Ackerman 2000; Campante, Chor, and Anh Do 2008). The new regime confronts a range of institutional problems: lack of state legitimacy, inability of public agencies to pay employees a living wage, lack of preparedness on the part of leaders for political competition, unequal distribution of power resources, and societal fragmentation (Johnston 2000

To return to the central theme of this article, there is a period of time in most newly democratic states before there evolves an effective system of accountability that brings power holders to account. Regime change is generally not accompanied by a corresponding shift in the political culture towards one more suitable to democratic values. The new policy makers are generally inexperienced in formal governmental affairs, and legislative supervision of the executive and service providers is still ineffective. In the case of Argentina, for example, a lack of political experience left politicians incapable of dealing with experienced senior bureaucrats who had customarily exercised excessive discretionary power during the authoritarian period (Eaton 2003). And in the new Indonesia, political uncertainty causes politicians to focus on short-term rather than long-term issues, resulting in less attention to monitoring the performance of the government agencies that could enhance accountability (World Bank 2003c, pp. vii-viii).3 This is hardly surprising, because political parties in newly democratic countries tend to be “power hungry” after a long period of being detached from genuine political processes; parties that were previously not able to develop a strong presence within the parliament now want to stay in office, reducing the effectiveness of parliament as an arena for social control of politics.

Additionally, we should bear in mind that not all politicians in a new democratic era are supportive of democratic principles. They may maintain a “reformist facade,” but many are self-serving and seek personal wealth through illegitimate means. The old “informal” rules still apply because the new formal rules have yet to take effect. In fact, once in power, many actually work to preserve undemocratic practices. In Indonesia, for example, the judiciary and police used to function as instruments of the corrupt regime rather than of law enforcement; the disappearance of authoritarian figures may have provided corrupt officials with even more freedom to pursue rentseeking opportunities (Lindsey 2002, pp. 2-12).

These conditions are usually aggravated by the fact that citizens in developing democracies have limited capacity to monitor state authority; political inexperience renders them less able to monitor the performance of politicians. Although voter enthusiasm in elections was high in the newly democratic Indonesia, most voters remained unaware of how elections could promote official accountability (Soule 2004, p. 2). Due to a lack of information about both the new political system and the track record of politicians, voters had insufficient knowledge when voting (Soule 2004, pp. 2-3). Such lack of social control is exacerbated by the tendency for politicians to rely on using money and “clientelist impulses”4 to attract voters (Keefer 2002, p. 26). Moreover, political parties often prefer a proportional representation system, making individual politicians reliant on party leaders rather than their constituents for both political survival and success (Sidel 1996; Carothers 2002, pp. 9-14). As a result, elections and other forms of political competition do not function as a means for social control of political life.5

Further, citizens are generally unable to effectively monitor the various functions of the bureaucracy for some time following the change of regime; they are still learning how to voice their demands. For its part, the bureaucracy is still subject to an authoritarian culture in which it functioned as the protector of the political class rather than an impartial public service provider. In Indonesia, despite the public’s growing awareness of its rights, the price of collective action is typically high; rather than struggling for their rights, people may find paying bribes more convenient and often cheaper (World Bank 2003c, p. viii).

In a context in which reformist organisations, the market sector, and the media are generally weak, attempts to constrain the government are very difficult, and sometimes impossible. These conditions enable monopoly systems to develop; corruption within governmental structures becomes institutionalised. Frequently, these deficiencies are maintained by a handful of private interest groups that extort private “rents” from public resources, as well as influencing state policies and regulations. Together with powerful decision-makers, these groups develop a “vested interest” in corruption (Kaufmann 2003, p. 21; Johnston 2000b, p. 10). Powerful political-economic structures emerge, characterised by a close interconnectedness between privileged parts of the business sector and the government. In such circumstances, corruption is not merely a problem for the government, but also for the economy itself.

Taking these structures into account, overcoming corruption in democratising developing countries thus represents a complex and multidimensional challenge. Although the end of an authoritarian regime is a necessary and important step, it is not the panacea that many expected. Democratisation needs to be accompanied by a number of initiatives to make government more effective. In mature democracies, the development of the basic institutions of a state governed by principles such as the rule of law and government accountability took place over a very long period. In the West, broad public participation associated with this process took hundreds of years to develop, and was shaped by historical events such as the signing of the Magna Carta in England in 1215 and the political revolution in France (1789-1799). Do then the emerging democracies of today also need to follow the long historical trajectory mapped out by Europe?

Essentially, new democracies need to develop the basic institutions of a modern state, one that is governed by the rule of law and accountability (Johnston and Kpundeh 2004, p. 5). Crucially, reformers in developing countries need to establish the political primacy of these principles more quickly than was the case in the West, for the political pressures associated with globalisation demand that governance issues are resolved. Increasingly, we find that CSOs are thrust forward to take up this historical role.

To this effect, reform initiatives are generated by credible actors who can persuade both the elites and ordinary voters that reform is important and in their interest to support. As widely acknowledged, civil society leaders were crucial in toppling authoritarian regimes and pushing for democratisation (O’Donnell and Schmitter 1986; Rueschemeyer, Stephens, and Stephens 1992; Diamond 1994, p. 5; Haynes 1997).6 In the post-authoritarian developing countries where the state is weak or unable to play its part in combating corruption—or when government and business actors are generally apathetic to the reform agenda—CSOs have taken the leading role in establishing the rule of law. And because ordinary citizens in developing democracies usually have little capacity to take significant action, CSOs serve to bridge this gap. They commonly mediate between those who govern and those who are governed, enhancing responsibility as well as responsiveness on both sides (World Bank 2000, pp. 44-45; Cornwall and Gaventa 2001).

At this point it must be acknowledged that CSOs face a number of internal structural obstacles to becoming effective agents of social change. They are generally financially insecure, face difficulties in attracting skilled personnel, and often have highly personalised and inefficient management structures. CSOs are also prone to becoming instruments for particular political elites (Hedman 2001). While it is beyond the scope of this article to describe in detail the reorganisation often required for CSOs to function effectively,7 it has been found that their capacity to build coalitions with other societal agencies serves to overcome such internal financial and management constraints (McClusky 2002).

In fact, this capacity to build linkages gives CSOs a distinctive characteristic, enhancing their effectiveness in fighting corruption. Political parties may not want to initiate an anti-corruption reform agenda, for they tend to represent particular interests that seek to gain access to institutional power. By contrast, CSOs generally have little interest in winning formal political power. Accordingly, CSOs are more likely to express a genuine concern for the public interest (Pietrzyk 2003, p. 42). In such circumstance, CSOs can serve as independent bodies to apply pressure for the activation of accountability mechanisms within the structures of political power. And, by persistently combating corruption, they can stimulate a successful process of democratisation and the formation of good governance.8

1Such mechanisms typically include: the existence of elected officials; secret ballots; free, fair, and frequent elections; political and economic competition; universal suffrage and citizenship; freedom of expression and participation; alternative sources of information; associational recognition; and the liberalisation of markets. See for example Dahl (1998) and Held (1995). 2The CPI refers to the perceptions of the degree of corruption according to business people and country analysts, and ranges between 10 (highly clean) and 0 (highly corrupt) (TI 2010). In 2010 the levels of CPI in a number of newly democratic countries were: Albania (3.4), Argentina (2.9), Bangladesh (2.4), Brazil (3.7), Bolivia (2.8), Cambodia (2.1), Indonesia (2.8), Jamaica (3.3), Lebanon (2.5), Nicaragua (2.5), Philippines (2.4), Poland (5.3), Romania (3.7), Serbia (3.5), Thailand (3.5), Ukraine (2.4), and Uzbekistan (1.6). These levels were far below those of developed democracies, such as Finland (9.2), New Zealand (9.3), Sweden (9.2), Denmark (9.3), Australia (8.7), Norway (8.6), United Kingdom (7.6), and Canada (8.9). 3When dealing with government agencies, for example, politicians in democratic transition countries do not have sound recordkeeping and documentation practices, and tend to pursue illicit deals rather than undertaking proper monitoring for the purpose of accountability (World Bank 2003c, p. viii; Reinikka and Svensson 2002). 4A classical definition of this socio-political form is the patron-client relationship “in which an individual of higher socioeconomic status (patron) uses his own influence and resources to provide protection or benefits, or both, for a person of lower status (client) who, for his part, reciprocates by offering general support and assistance, including personal services, to the patron” (Scott 1972, p. 92). 5For further examination of the dynamics of political competition and the relationship between voters and politicians in a number of countries undergoing a democratic transition, see Moran (1999, 2001), Rose and Shin (2001), Foweraker and Krznaric (2002), Keefer (2002), Soule (2004), Khan (2005, pp. 717-21), and Webber (2006). 6Civil society actors played a significant role in fostering the end of authoritarian regimes in Eastern Europe (Bernhard 1993; Miller 1992), in Indonesia (Nyman 2006), and in the Philippines (Wurfel 1988). 7This issue is discussed in depth in Chapter 6 of Setiyono’s 2011 thesis, “Organisational Challenges for the Anti-Corruption CSOs: Resources, Integrity and Public Support.” See also Chapman and Fisher (2000), and Jenkins and Goetz (1999). 8While the term “governance” has multiple interpretations, it is generally understood to represent a decreasing role for government in organising state authority. More importantly, governance is not only about the institutions or actors; it is also about quality and values. “Good governance” usually connotes principles such as active public participation, transparency and accountability, effectiveness and equitability, and the rule of law. These principles ensure that political, social, and economic priorities are based on broad consensus in society, and that the voices of all the people are heard when decisions are made about the allocation of development resources (Abdellatif 2003, pp. 3-4).

The Importance of Developing a Culture of Accountability

Successful efforts to combat corruption require more than establishing powerful political institutions. Perhaps the most important constraint on misuse of power is the general socio-political climate in which an official operates. As the World Bank notes, the major element that allows corruption to flourish in many countries is a “lack of transparency and accountability based on the rule of law and democratic values on the part of public officials,” which leads to a “distortion in policy priorities” (World Bank 2005, p. 22). Accordingly, in order to prevent corruption, it is necessary to develop both effective accountability mechanisms and a political tradition of public accountability.

Accountability obliges both officials and social figures to act morally. In a democratic environment, accountability is the most important instrument for the on-going correction of mistakes so as to preserve mechanisms that ensure protection of the rights and interests of the people. Accountability works to uphold the “social contract” between citizens and government (Blanchard, Hinnant, and Wong 1998). Government has to be responsible to the people for its actions and faults; if a government performs well, public support will continue, but if a government makes mistakes, citizens will demand explanations, reparations, resignations from office of the persons responsible, or even that the government takes steps to “shut down the agency in question” (Scholte 2004, p. 211).

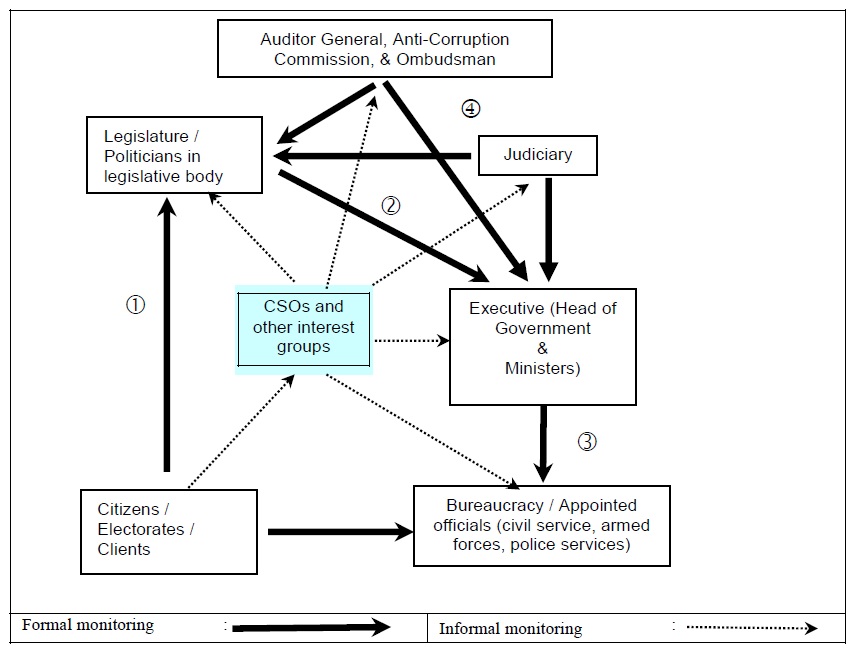

How then might such an accountability mechanism become an integral part of the political system? As illustrated in figure 1, an effective chain of accountability comprises a number of key formal relationships: between citizens and their representatives in the political legislature; between the legislature and the executive (head of government and cabinet ministers); between the ministers and the bureaucracy as the front-line service providers; and, finally, between the service providers and citizens. In this sense, a functioning accountability mechanism serves as a map of the governmental processes in a democracy, one in which unpopular actions on the part of public officials may result in new sanctions brought by citizens (Philp 2001, p. 361).

This framework can help us better detect failures that contribute to corruption at different levels of the accountability chain. The theory of PAC (principle-agent-client) provides a useful means to apply this framework. This theory is a market-based concept that describes the mechanisms involved in the interactions between a buyer (the principal) and a seller (the agent).9 According to this theory, corruption usually arises when two factors are present: a “divergence of incentives” (the interests of the principal and agent diverge) and an “asymmetry of information” (the principal has insufficient information about the performance of the agent). Agents thus have an incentive to hide information (Klitgaard 1988, p. 75).10 Agents may behave corruptly if they believe that the benefits would exceed the risk of discovery and associated legal, psychological, and social damage. On the other hand, corruption will be discouraged if this calculation is unlikely: Every link in the chain of accountability functions properly such that monitoring by the principal works against the possibility that the agent might consider that the benefits exceed the risk.

As outlined in figure 1, the chain of formal accountability begins with link 1, namely between citizens and politicians; the monitoring mechanism is carried out through free and fair elections. In this link, people select politicians who they believe are capable of realising their aspirations. In addition to facilitating leadership succession, elections function implicitly as a mechanism of “contingent renewal,” whereby the people decide to either extend or terminate the tenure of a government (Manin, Przeworski, and Stokes 1999, p. 10). This ensures that elected politicians and ministers oblige their ministries and service providers to serve the interests of the people. The uninhibited flow of information is necessary for this link to function as an effective accountability mechanism; elections need a degree of “merit competition,” one that enables the citizens to judiciously evaluate the performance of contestants in both a retrospective and a prospective manner (Adsera et al. 2003, pp. 447-48). Making such a judgment requires, in turn, a transparent political system that allows exchange of information about what

In the next link in the chain, namely link 2, the legislature monitors the performance of the executive by various means, including budget allocations, financial and performance reports, and through third-party institutions such as supervisory bodies (anti-corruption commissions and ombudsmen) and external auditors (auditor-general). Legislatures may still encounter two possible handicaps in using these instruments:

In the next formal link in the chain of accountability, namely link 3, the executive (especially the ministers) monitors the bureaucracy or service providers by means of legal frameworks, internal auditors, and systems that ensure ethical conduct such as reward-punishment systems (by means of salaries, incentives, administrative sanctions, legal actions, etc.). A recent notion of public organisational configuration and management called New Public Management (NPM) proposes that bureaucracies follow the forms of accountability developed for private organisations (Parker and Gould 1999). This link in the chain of accountability requires the bureaucracy to adhere to a number of organisational principles, including sound policy management and implementation; performance evaluation and explicit targets for efficiency, effectiveness, and quality; output and outcome targets; strategic corporate plans; and quantified benchmarking of performance targets. This recipe transforms bureaucrats from administrators and custodians of resources into managers empowered with greater delegated authority, but with an orientation towards achieving specified results (Parker and Gould 1999, p. 111).

Formal accountability mechanisms may be further strengthened by the existence of non-governmental state institutions such as Auditors-General, Anti-Corruption Commissions, Ombudsmen and, most importantly, an independent judiciary (link 4). These institutions are given the task of ensuring that all public agencies work in accordance with the rule of law. Such institutions function as instruments for “horizontal accountability”; they may call into question, and eventually punish, improper ways of discharging the responsibilities of a given office (O’Donnell 1999, p. 165).

Such formal mechanisms of accountability do not automatically curb corruption, however. To function effectively, these mechanisms need to be supported by a number of general political pre-conditions: a significant degree of political competition, competent actors in every link of the chain, the existence of clear regulations that make clear both of the rewardpunishment and check-and-balance mechanisms, free access to information, and a high degree of transparency in the governmental and political systems (Lederman et al. 2005, p. 4; Quirk 1997; Strøm 1997). In other words, the success of such formal accountability mechanisms depends on the broad social and cultural climate in which they are applied.

Most importantly, only the close monitoring of governmental institutions by the citizenry will ensure that they function effectively. Citizens need to voice their appreciation, concern, or dissatisfaction with the quality of the institutions’ performance. When such monitoring is strong, the poor performance of public officials or institutions will be brought under public scrutiny, making them less likely to ignore or abuse their obligations in the future. Furthermore, citizens need to be able to attain necessary information, analyse situations, and organise political activities in order to understand how public agencies function as a means of undertaking such monitoring. Hence, because individual action is usually not effective, citizens need to develop community-based activities grounded on a set of common interests.

As illustrated in figure 1, CSOs can facilitate such activities, acting as advocates for citizens and holding individual government officials to account. In other words, in order for policy reforms to be implemented effectively, CSOs must become the source of pro-accountability measures, by “asking,” “accelerating,” and “empowering” state actors to deliver the expected outcomes (Schedler 1999, p. 338).

9PAC theorists generally deny moral issues, focusing instead on the rational choice of individuals to undertake corrupt transactions (Rose-Ackerman 1978). 10In this case, principals are those who give their authority to other parties to act on their behalf; agents are those who are obliged to execute that action.

Civil Society, Democracy, and Policy Implementation

CSOs thus have the potential to significantly contribute to corruption eradication efforts. As illustrated in figure 1, shortcomings in the formal accountability system require CSOs to take a more prominent role in developing countries. They can contribute by generating more effective relations between the state and its citizens, thereby enhancing the vertical dimension of accountability. They can raise the expectations of the public about the performance of state officials, and thus, apply pressure on the state to comply with citizens’ demands. CSOs can also activate effective checks and balances between state institutions by initiating institutional oversight frameworks that reveal abuses of power, while pressing legal agencies to act against the abusers. They can thereby also enhance the horizontal dimension of accountability. These activities often correct erroneous decisions and help eradicate systemic corruption or other distortions of accountability (Fox 2000, p. 1).

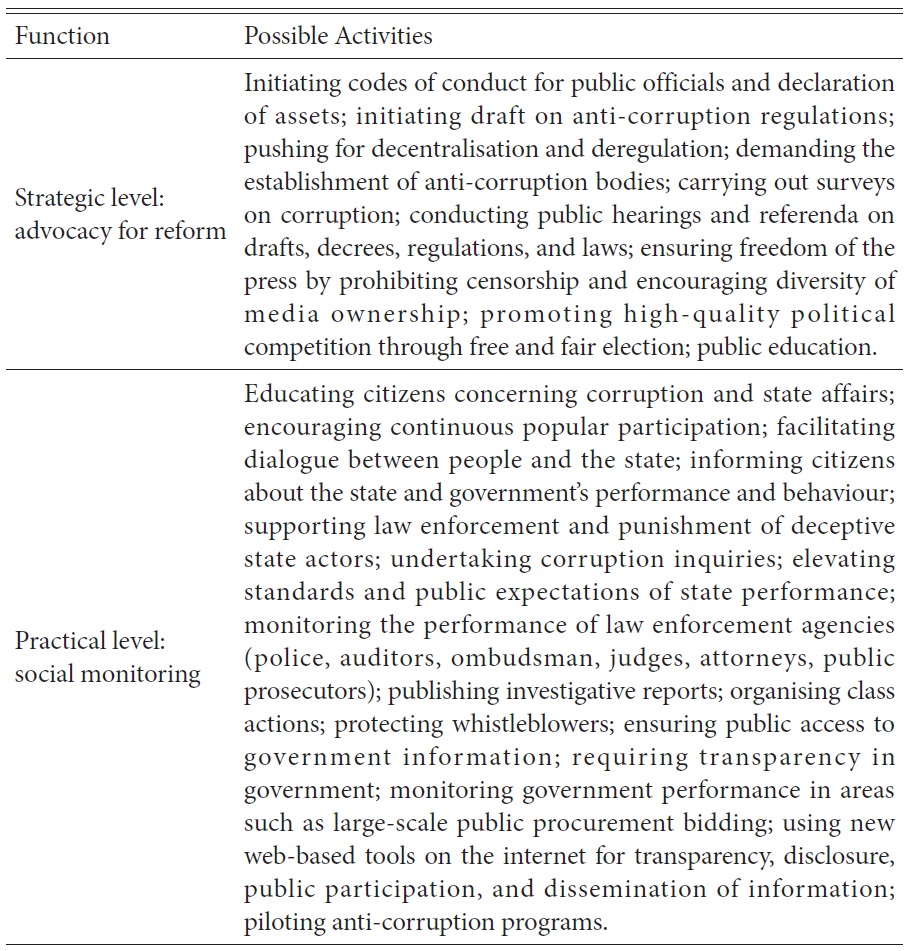

More specifically, and as detailed in table 1, CSOs operate at two levels in reforming accountability and anti-corruption protocols. At the strategic level, CSOs endorse policy reform for strengthening the check-and-balance mechanisms between state institutions. They play this role by helping to formulate anti-corruption policies and taking the lead in the effort to build strong legal and institutional frameworks.

Such activity at this strategic level might not have an immediate impact, but is very significant indirectly. In order to bear fruit, it is important that efforts to combat corruption are carried out in a context of strong laws and regulations, without which they would be ineffective—if not counterproductive. CSOs should thus analyse the causes of corruption in a particular setting, and offer solutions to policy makers. And CSOs can encourage politicians and policy makers to draft the anti-corruption regulations that can stimulate the functioning of effective accountability mechanisms. CSOs also need to promote the formation of state agencies specifically assigned to eradicate corruption. Their role in strengthening the capacity of such agencies is crucial because the performance of formal judicial institutions in developing democracies is usually poor; they often act to protect corrupt groups, as we have seen.

[Table 1] CSO Activities Supporting Accountability and Anti-Corruption Reforms

CSO Activities Supporting Accountability and Anti-Corruption Reforms

New legal and institutional frameworks will thus only succeed if citizens organise themselves effectively to oversee the implementation of anticorruption regulations. These “strategic level” activities thus have to be taken in conjunction with those at a practical level, whereby the community is organised to monitor state institutions and demand that policy reforms be realised. At this level, CSOs mobilise citizens to actively monitor the behaviour and performance of state institutions, as well as the work of anti-corruption agencies. CSOs themselves can thus function as agencies to independently monitor government activities. As suggested by Fox (2000), CSOs can impose accountability on the state by detecting and exposing abuse of power, by elevating standards and, thus, the public’s expectations of state performance, and by exerting political pressure. This important “watchdog role” of CSOs has decreased the occurrence of corruption in a number of countries. As various studies have found, CSOs around the world have successfully combated corruption, not only detecting and revealing particular cases, but also bringing corrupt figures to justice (TI 1997, 1998; Gonzalez de Asis 2000; Pope 2000).

In the performance of such practical activities, CSOs need not be detached from governmental processes. In fact, and as illustrated in table 1, they also maintain a wide range of dynamic relationships that serve to interconnect government and citizen. For example, in his evaluation of the World Bank’s multilateral development bank (MDB) projects, Fox (1997) finds that CSOs in several countries were able to increase their effectiveness by not only monitoring and supervising aid flows, but also helping in their execution. Similarly, social monitoring and facilitation stimulated by CSOs has proved vital in ensuring the clean implementation in several countries of another World Bank project, the “Poverty Reduction Strategy” (PRS) (Barbone and Sharkey 2006).

Despite the significant social benefits that are derived, such endeavours are often resisted by social elites and their patrons. CSOs thus need to be able to fight off pressures from vested interest groups in a professional and wellinformed manner. Importantly, CSOs cannot work alone in this endeavour; they need to build a broad coalition to have significant impact. For this reason CSOs have made long-term efforts to encourage all stakeholders to act collectively.11 Groups within the media, academia, and the business sector have been involved in such coalitions. Ultimately, this may in turn encourage politicians to support anti-corruption reforms because they will also benefit from improvements in popularity, international image, legitimacy, and the likelihood of their own political survival (Johnston and Kpundeh 2005, pp. 162-63).

It is certainly undeniable that CSOs in developing countries will encounter difficulties in forming such a political constituency simply because anticorruption efforts generate risks for state officials. Civil servants often find anti-corruption campaigns threatening: Honest officials may fear being mocked when they cooperate with CSOs, while dishonest officials will raise obstacles to efforts to expose and punish their illicit activities (Klitgaard 1991, p. 97). And there are always fewer groups that have a stake in anti-corruption measures than, for example, lobbies for promoting soy production or new education facilities. Although it is possible to launch a wide-ranging anticorruption campaign while there is a wave of public resentment against the former authoritarian regime, institutionalising and sustaining such public concern is not always easy. Against such a socio-political backdrop, the success of CSOs in combating corruption during the turmoil unleashed by a democratic transition will be determined by both their internal organisational capacity and their ability to develop strong networks with emergent political forces.

11This idea has been recognised in international anti-corruption forums. The United Nations, for example, has adopted the term “interagency coordination” to strengthen horizontal and vertical coordination, as (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2010, p. 29). “International Group for Anti-corruption Coordination” (IGAC) (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2010, p. 29).

The need for CSOs to build strong networks with various social forces during a democratic transition brings us back to the issue implied in the title of this article: What is the nature of the relationship between civil society, anti-corruption measures, and the success or failure of the democratic transition? More specifically, what should be the role of CSOs in establishing respect for the rule of law? Can their activities help build trust in the institutions of the state? Or is the success of anti-corruption efforts contingent upon prior consolidation of democracy?

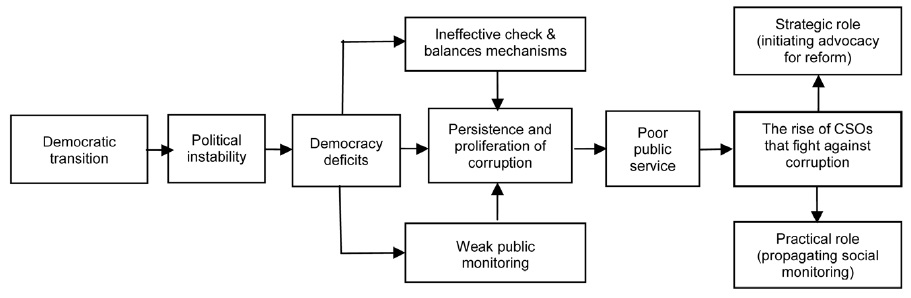

Clearly, democratisation alone is not a sufficient remedy for corruption. In fact, democratization usually creates political instability, making law enforcement and accountability mechanisms more difficult. Also, governments in transition are generally inexperienced in the implementation of measures to combat corruption. Because of this lack of state capacity, civil society actors bear more responsibility for strengthening accountability mechanisms. Rather than ineffective politicians, bureaucrats, or business groups, CSOs must shoulder the responsibility for realising this vital element of the democratic consolidation. A schematic representation of the critical role of CSOs in dealing with corruption in transitional democracies is suggested in figure 2.

The initial political “opening” that usually precedes a democratic transition does serve to empower anti-corruption CSOs. The lifting of restrictions on civil rights following the fall of an authoritarian regime enables CSOs to coordinate collective action to monitor the behaviour and performance of political and bureaucratic agencies, as conceptualized in PAC theory. CSOs may thus act as representatives of the public, allowing the principal to hold its agents to account.

The enhanced role of CSOs in a number of developing countries suggests that democratisation presents the CSOs with a greater degree of political influence. As is also illustrated in figure 2, the role of CSOs in dealing with corruption is not limited to serving as watchdogs that expose misappropriations in the state sector: They also have an interest in ensuring that every link in the accountability chain within the government system operates smoothly. In other words, CSOs can not only increase the risks associated with corruption by conducting external monitoring and bringing corrupt figures to justice, they can also reduce the likelihood of corruption by initiating policy reforms and ensuring their implementation.

We might think of this latter function as comprising two “feedback loops,” whereby CSOs’ strategic role in advocating policy change and their instrumental role in monitoring policy implementation reinforces the democratic transition itself. The extent to which CSOs become influential actors in a new democracy will thus depend on the extent to which they are able to increase their operational efficiency and strengthen their links to other social forces. If they are able to undertake these tasks successfully, they can thereby make a significant contribution to processes of social change in emerging democracies.