Under the influence of the 1995 UN Women’s Conference in Beijing, the term “domestic violence” by the West was first introduced in the Chinese research field. Moreover this term is gradually being substituted for the traditional terms

In particular, and thanks to the efforts of Chinese academics and practitioners, domestic violence has begun to be seen not as a

However, the history of domestic violence research is much shorter in China (just over ten years) than in the West (over thirty years). Researching domestic violence is so new for Chinese academics that there may be a few issues in the process of research. For example, it may remain limited, political and less systematic or scientific. Examining the literature on this field, the author saw that the previous studies might have focused more on the prevalence of domestic violence, for example, how much husbands violate their wives, and how much wives suffer from such violence by their husbands. According to this result, it might be difficult to see how couples actually behave in the home. The author also saw that the previous studies might have focused less on experiences, impacts, and gender-based relationships between victims and perpetrators. This implies that the previous studies might only rarely reveal why and how domestic violence occurs in the home. In particular, having reviewed the literature, the author saw that some of the previous studies ignored practical investigations while paying more attention to discussing some abstract contents, covering strategies/measures against domestic violence, which may have been influenced more or less by politics. Imaginarily, if the researcher does not explore domestic violence deeply in practice, how can he/she understand its issues at a deeper level? How can he/she provide substantial and detailed data to the central government that has power to make policy and law? If the government lacks the real data, how can it make good policy and law for people to stop domestic violence? Thus, the author considers that a key point for the researcher should be to explore the practical aspects of domestic violence. The author further saw that some of the previous studies failed to provide a detailed description of the research process, an omission which has an impact on the readers who cannot estimate and learn from this research. For instance, the previous studies concluded that psychological domestic violence occurs more in intellectual families than in non-intellectual families (Ling, 2005; Ma, 2003; Y. Wang, 2007; Y. Zhao, 2008). This view may mislead the readers because there was a lack of practical or persuasive data to support such a conclusion. Also the previous studies did not specifically show how wives behaved in conflict. According to these issues in research, the author suggests that the researcher should consider them carefully, which would benefit the development of the Chinese research on domestic violence.

As Lee and Stanko (2003) point out, domestic violence is a very sensitive topic and research because it is fraught with difficulties. Through the research, academics suggest that domestic violence includes a variety of types such as physical violence, psychological violence, sexual violence and so on (Feng, 2008; Qu, 2007). In particular, the results revealed that psychological violence as a form of domestic violence is very common in all forms, including physical, psychological or emotional, sexual and financial aspects (Horley, 1988; Kelly, 1988; Mooney, 2000; Qi, 2004; Smith, 1989; W. W. Li, 2003). For instance, in the UK, about half of women (48%) have experienced frightening threats (Walby & Allen, 2004), while in China the phenomenon of psychological violence appears to be widespread: according to the Police Report Centre in Dalian City, 70 or 80 per cent of cases, among 834 cases of domestic violence, dealt with psychological violence (Tang, 2003; W. Li, 2003). Such violence therefore has been a prominent concern among academics (Feng, 2008; Qi, 2004; Zhai, 2005).

However, why does psychological domestic violence occur more frequently between husbands and wives? What specific forms of such violence do perpetrators employ to abuse their partners? How does such violence occur in the home, particularly between husbands and wives? Is there a difference in such violence by husbands and wives? Do they use/experience psychological domestic violence differently? Is there an issue of gender inequality in such violence occurring between husbands and wives? Whether the occurrence of psychological domestic violence between husbands and wives is linked to an understanding of gender in aspects of history, society and culture? These questions might have been analyzed and discussed less in the previous studies. Thus, the author will study such questions and try to find answers to them.

>

Psychological Violence (‘Cold’ Violence)

Two levels of psychological violence are conceptualized by Western and Chinese writers. One is the effect of physical abuse on victims’ emotional state. Another is “pure” psychological violence without physical behavior/injury (Kirkwood, 1993; Lan & Jin, 2002; Ye, 2010; L. Zhang & Liu, 2004). The former means that physical violence leaves emotional scars on its victims, and can cause anxiety and a range of other psychological symptoms and difficulties within relationships. Thus, victims can experience emotional abuse and threats in addition to physical violence (Horley, 1988; Hague & Malos, 2005). But the latter indicates that such violence does not accompany physical violence. In contrast to physical violence, psychological abuse is an attack on the victims’ personalities rather than on their bodies. This type of violence is enacted at a purely emotional level, and consists of such things as verbal insults and emotional deprivation (Kirkwood, 1993). The author’s study focuses on this “pure” type.

Psychological violence is a newer term – equivalent to the term “domestic violence” (Y. Wang, 2004) – for what has been called “cold” violence in China (Guo, 2004; Hu & Zhang, 2003; Hou, 2006; Tian, 2009; Yan, 2005; Yi, 2008). The term ‘cold’ violence occurs much more often than the term “psychological violence” in newspapers, magazines and journals, television and broadcasting programs, and even academic reports, so that this term usually substitutes for the term “psychological violence” in China. Why do the Chinese academics prefer “cold” violence to psychological violence in practice? This is because such violence is the opposite of “hot” violence (physical violence) within the Chinese context (J. Li & Ma, 2003; Lie, 2003; W. Wang, 2007). When “cold” and “hot” are compared in Chinese, the former usually links with moon, water, cool, darkness, passivity, indifference, inferiority, while the latter links with sun, fire, heat, lightness, activity, friendliness, superiority, and power (Rydstrøm, 2003). Accordingly, “cold” violence impacts on victims invisibly, without causing a wound or without bleeding, but “hot” violence apparently impacts on victims visibly, causing a wound or blood (Chen, 2007; Q. Ye, 2011a). “Cold” (psychological) violence therefore is likely to be neglected (C. Zhao, 2007) because victims may find it difficult to tell their stories to others (Q. Ye, 2011a). When perpetrators use such behavior to abuse their partners, its harm will leave psychological scars on victims (Kirkwood, 1993). Such scars cannot be healed (Mooney, 2000, p. 33).

Within this context, Chinese academics separate psychological violence from other forms of domestic violence and explore it in different ways. This is in contrast to the research conducted by UK scholars and practitioners (Ye, 2010). Chinese academics make this separation because of the Chinese legal and cultural context (Ye, 2008). Regarding the legal context, prohibition of domestic violence was first stipulated in Marriage Law only in 2001 and this law contains only a non-explicit definition of psychological violence (Liu, 2007; The Group, 2010; Ye, 2008, 2010). This may influence the Chinese people’s awareness of what is psychological violence. In daily life, perpetrators may not know that their abusive behaviors such as non-communication, threatening gestures and dirty language and so on to their partners in the home are called psychological violence, while victims may also not know that they are experiencing these abusive behaviors belonging to psychological violence. Moreover the abstract items in the law influence lawyers’ judgment regarding cases of psychological violence in court (The Group, 2010). Because of this, a special law-China Law on the Prevention and Punishment of Domestic Violence-will be promulgated soon.

Within this context, Chinese academics, through their research, specially define “cold” violence in a manner which focuses mainly on its forms and helps people to understand what such violence is. As some writers point out (X. Wu, 2000; W. W. Li, 2003; Luo, 2005; Qi, 2004; Qu, 2007; Zhou, 2002), “cold”/psychological violence includes when one partner of a couple threatens, intimidates and abuses the other, which leads the other to having mental illness; when one partner threatens another, destroys furniture, hurts animals, batters and intimidates children, which leads the other to anxiety and feelings of insecurity and safety; when one partner often maliciously depreciates, criticises, humiliates, scoffs at, ridicules and hurls insults at another publicly or privately; when one partner often makes things difficult for, interferes with, doubts, prevents or restricts the personal freedom of another, which negatively influences the normal work and life of the other partner; or, finally, when one partner openly brings a new partner, a “third” party to the home, and cohabits with the third party, thereby humiliating the spouse.

But other Chinese academics in their definitions mainly emphasize behavior used by husbands and wives in conflict. For example, in conflict perpetrators usually are indifferent to, look down upon, and/or are estranged from their partners. Specifically, perpetrators’ behavior may be reflected in not caring, communicating with, or stopping or perfunctorily having sexual activities with their partners, and laziness in doing household tasks. “Cold” violence reveals behavior by husbands and wives that is manifested more in maltreatment and abusive language, e.g. swearing or depriving the right of finance (L. Wang & Zhang, 2005). Their definitions enable people to picture what psychological violence is. Thus, “cold” violence, in comparison with “hot” violence, is more hidden and enduring. Such violence is called an invisible “soft knife” (Liao, 2003) and impacts seriously on victims (Ye, 2010). Noticeably, the author uses the term “psychological violence” in this article rather than “cold” violence because the former, at an academic level, is the universally-accepted term in this field.

The author focused on psychological domestic violence because such violence can be seen as a social issue and one of mental health as well (R. E. Dobash & R. P. Dobash, 1992; Pahl, 1995; Pryke & Thomas, 1998; Yang, 2003; Williamson, 2000; Q. Ye, 2011a). As described above, psychological domestic violence occurs prominently between husbands and wives and can take many forms. Aggressors may, for example, use verbal abuse, including shouting, ridiculing, using an insulting nickname, humiliating, using foul language and so on, or non-verbal threats, including facial expressions, body gestures, and other non-verbal behavior such as neglect, non-communication, turning a “cold shoulder”, isolation, deprivation, etc. (Ye, 2008). With regard to verbal abuse, when asked to choose the ‘worst’ type of psychological violence, 51 per cent rated ridicule as the hardest to deal with (Hanmer, 2000). With respect to non-verbal abuse, according to the survey by the China Law Society, 65 per cent of husbands did not communicate with or neglected their wives when there was conflict between husbands and wives (Cui, 2002; Z. Yang, 2004; Yin & Jiang, 2007). Such verbal humiliation and non-verbal abuse lead victims to anger, shame, depression and a lack of self-confidence and loss of self-esteem (Goldsterin, 2002; J. Zhang, 2005), which has been reflected in the author’s previous research. For example, in the one survey the author, 52.3 per cent(92/176)of the respondents reported that they felt very “angry” when suffering “dirty language” by their partners. Consequently, both these verbal and non-verbal behaviors can be called psychological abuse (Ye, 2008) and cannot be neglected.

The author conducted this research also because domestic violence can be seen as a gender issue (Hanmer, 2000; Jackson & Scott, 2002; Q. Ye, 2011b). Overall, women experience domestic violence differently in the home than men do, to the extent that they have been the main victims of this violence. For instance, in the UK 32 per cent of women had experienced domestic violence from this person four or more times compared with only 11 per cent of men, while in China more than 89 per cent of men have violated their wives by domestic violence at some time (Huang, Sun, & Lu, 2003; W. W. Li, 2003; Liang, Wang, & Xiao, 2004; Zhao, 2008). The author’s previous study showed that 18.1 per cent of wives used dirty language as a form of psychological violence to their husbands, while 46.5 per cent of husbands used dirty language to their wives in conflict. One in five of the female interviewees (20%, 8/40) had experienced the introduction of a ‘third party’ into the household, while only one male interviewee (2.5%, 1/40) had experienced it (Q. Ye, 2011c).

Importantly, as Thomas (1977) suggests, in marriage and family relationships, communication is one of the primary activities marital partners engage in together, and it can be seen as a standard for measuring marital satisfaction. Communication, as Noller (1984) argues, affects marital satisfaction, and marital satisfaction in turn affects communication. The more and healthier the communication between spouses, the happier they may feel (Fitzpatrick, 1988). However, as shown in the above results, cases of verbal or non-verbal abusive behavior occurs often between husbands and wives. These abusive forms, which are closely linked to communication between husbands and wives in the home, have a serious impact on their marriage life.

The author therefore focused on communication between couples because their ability to communicate does much to determine their happiness together. If psychological violence occurs between husbands and wives, it means that the channel of communication between them has been obstructed. Why? Whorf (1976) suggests that language and communication are not only vehicles for carrying ideas, but also shapers of ideas and the programmers for mental activity. Poor communication will exacerbate the emotional problems of speakers and listeners, particularly those of the latter. Such uncertainty increases the potential for conflict (Noller, 1984) and directly influences the marital relationship. Accordingly, the subject of communication in marriage needs to be explored because communication is particularly important in marriage (Noller, 1984; Fitzpatrick, 1988; Q. Ye, 2011a, 2011c).

Finally, the author decided upon psychological violence as her research topic because in the literature, she found that a problem in relation to communication between couples is reflected in the previous studies done in China. For example, the previous studies might focus more on the results in relation to the prevalence of perpetrators (only husbands) using negative communication (verbal or non-verbal behavior) to abuse their wives. Also, the previous studies do not show

Research Design and Key Findings

Research methods are a central part of social science research (May, 2001). Methods arise out of scientific knowledge and researchers will develop them as they reflect and think about the research problems repeatedly (Hegel, 1969). Based on the principle of research methods, the author first thought about her research questions and made her research proposal, then started her empirical investigation of domestic violence in China. But her specific research aims were as follows: to investigate use/experiences of psychological domestic violence principally between married couples; to investigate the types of psychological violence such as specific verbal and non-verbal behavior that are used by husbands and wives; to investigate whether there is a difference in this violence between intellectual and non-intellectual families; to investigate how psychological domestic violence impacts on the victims; and to investigate why women are the main victims of such violence. Second, quantitative and qualitative approaches were used in this exploration, which is because the researcher, as Skinner, Hester, and Malos (2005) have stated, should try to find the “best” way to explore research issues. Therefore, the author specifically used both a self-completion questionnaire survey and a series of in-depth interviews to collect the data and also used both quantitative data analysis and qualitative data analysis to analyze all data in this project. Notably, the author will briefly describe only the process of her survey because of the chosen research questions to be discussed in this article.

Through using personal contacts for developing networks, the questionnaire data (the non-probability convenience samples) was collected in three different cities (Wuhan, Jingzhou and Xiaogan) in the Hubei Province of South-Central China between September and October 2003. Two hundred thirty-two respondents (

The questionnaire was divided into two sections. The first section was concerned with demographic information and invited the respondents to provide personal information about themselves and their spouses. The 24 questions covered aspects such as age, sex, place of birth, place or area of residence, level of education, occupation, marital or divorced status, marriage or divorced age, income and financial situation, office rank, academic and technical titles, and hobbies and interests. The second section formed the main body of this questionnaire. The 55 questions dealt with specific family problems such as a conflict between partners, abusive behavior, including verbal (e.g. dirty language, ridicule, etc.) and non-verbal behavior (e.g. non-communication, glaring, etc.), emotions and impacts caused by physical and psychological violence, and attitudes towards marriage.

Data analysis is an essential step in the process of research because researchers need to make their data speak (Ramazanoğlu & Holland, 2002) in order to shed light on the issues. Therefore, quantitative data analysis was used in this exploration. Faced with a large number of questionnaires (raw data), how do researchers analyze, including edit, code them by counting them manually or by using a computer? For the sake of accuracy and speed in data analysis, SPSS is a widely used and comprehensive statistical social science research program (Bryman & Cramer, 1999). Using SPSS, a large volume of questionnaires or complex data can be changed into readily understood clear data. Overall, there were 179 variables in the questionnaire, arising from 24 questions in Part I and 55 questions in Part II. Regarding the data analysis, the author chose to examine frequencies and cross-tabulations, and also used Chi-Square to test for significance especially with regard to gender and level of educational achievement. Nevertheless, in this article the author will mainly show the analysis of results with percentage because such results may simply reveal how husbands and wives used/experienced the non-verbal behaviors in conflict. As explained above, one of the purposes of this research was to find what types of psychological violence husbands and wives use frequently and whether they use them differently in conflict. Through data analysis, something new was found and acknowledged, which differs from what has been found in earlier studies.

Key findings in this article cover non-verbal behaviors: facial expressions, including “glaring”, body gestures such as “threatening with fists” and “stamping of foot”, which are used by husbands and wives in conflict. Although such non-verbal behaviors are usually ignored in research, they have a serious impact on victims because husbands and wives use them to convey their attitudes and intentions (usually hostile) to each other in conflict (Q. Ye, 2011a). With respect to “glaring”, perpetrators may use this (looking at their partner angrily and fiercely) to frighten victims, hinting that severe violence may subsequently occur between victims and perpetrators. With regard to “threatening with fists”, perpetrators may use this (wanting to batter their partner) to threaten their victims, again indicating to the victim the potential of physical violence. Concerning “stamping of foot”, perpetrators may use this (making noise to their partner) to protest against their partners and to express anger to them (Q. Ye, 2011a). The key findings in this survey indicate that the respondents reported that the three non-verbal behaviors were used in conflict, namely husbands and wives were likely to choose to practice such behaviors in conflict. The result also shows that husbands and wives used these non-verbal bahviors more or less differently in conflict, while there was no significant difference in such non-verbal behaviors between intellectual and non-intellectual families if gender is not taken into account. The specific results of data are as follows:

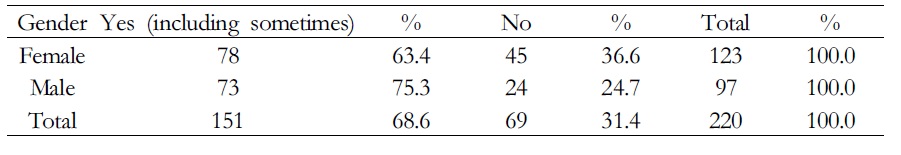

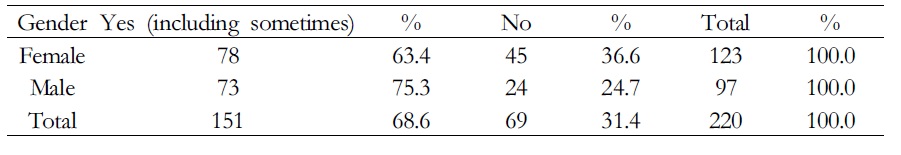

Table 1 (a) examines the gender pattern of “glaring” in a conflict. It shows first that the vast majority of respondents saw themselves as using such behavior, with more than two thirds answering “yes including sometimes” (68.6%, 151/2202). Only 31.4 per cent of the respondents (69/220) did not practice such behavior in their conflict. In relation to gender, there is a difference, with 63.4 per cent of females (78/123) and 75.3 per cent of males (73/97) answering “yes including sometimes” to “glaring” respectively. The latter is 11.9 percentage points higher than the former. Such results suggest that in this survey both wives and husbands choose to practice such behavior in their conflict, but that husbands were more likely to say that they use this behavior, although the Chi-Square test indicates that there was no significant difference in it between them (

‘When there is a conflict between you and your spouse, do you glare at your spouse?’(Q23) by gender of respondents

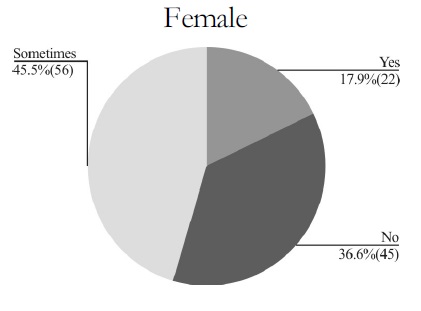

Pie Charts 1 (a) and (b) looks at the gender pattern of this behavior in detail. The results are similar to Table 1 (a) because husbands in this survey say that they practice such behavior more than their wives. The Pie Charts show that there appears to be a small difference in the practice of such behavior between wives and husbands. With respect to “yes”, the proportion of females is 17.9 per cent (22/123), while the proportion of males is 22.7 per cent (22/97). The latter is 4.8 percentage points higher than the former. With regard to “sometimes”, the proportion of females is 45.5 per cent (56/123), whereas the proportion of males is 52.6 per cent (51/97). The latter is 7.1 percentage points higher than the former. But the Chi-Square test indicates that there was no significant difference in using such behavior between husbands and wives (

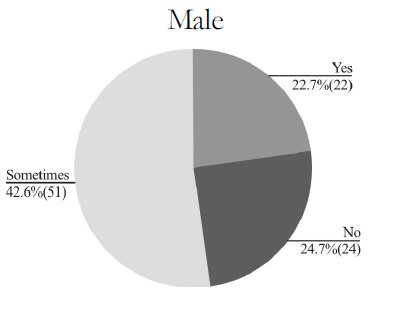

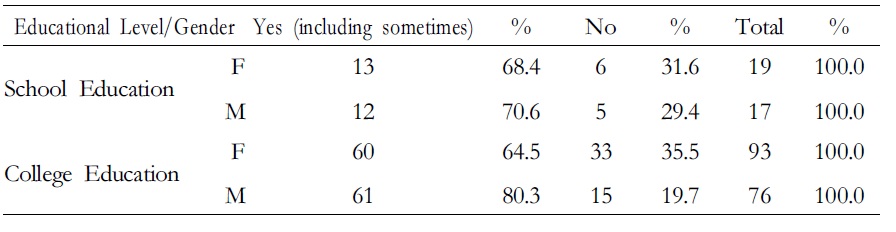

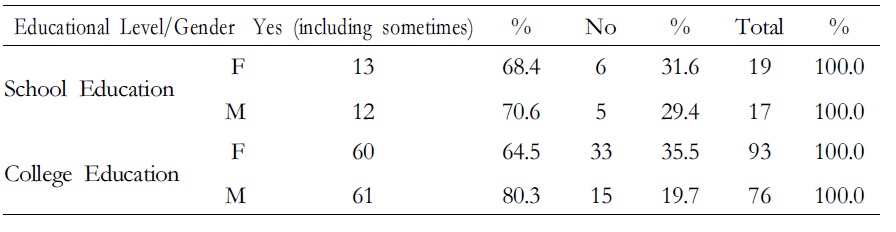

However, the picture becomes more complex when educational background is taken into account. Table 1 (b) shows that no matter what educational backgrounds both female and male respondents have, the majority of them may be likely to use “glaring” against their partners because the proportions of the four groups are over 60 per cent, a result which is similar to the results of the gender pattern of this behavior in Table 1 (a). Table 1 (b) also shows that there is a similarity in this non-behavior between wives (68.4%, 13/19) and husbands (70.6%, 12/17) with “School Education3” (

‘When there is a conflict between you and your spouse, do you glare at your spouse?’ (Q23) by gender of respondents with different educational background s5

Table 1 (b) suggests that a difference in “glaring” mainly occurs from husbands in both educational groups. Eighty point three per cent of husbands (61/76) with “College Education” said that they glared at their wives in a conflict, while 70.6 per cent of husbands (12/17) with “School Education” reported so. The proportion of the former is 9.3 percentage points higher than the latter. These results suggest that a high proportion of intellectual husbands may be likely to use such non-verbal behavior to abuse their wives in a conflict. Additionally, if we ignore gender when we compare the group “College Education” to the group “School Education”, the results are very similar. Seventy-one point six per cent of the respondents (121/169) in the former group said that they used this behavior in a conflict, whereas 69.4 per cent of the respondents (25/36) in the latter group said that they did so. Accordingly, the result in this survey shows that there may be almost no significant difference in this behavior between the two groups if gender is not taken into account.

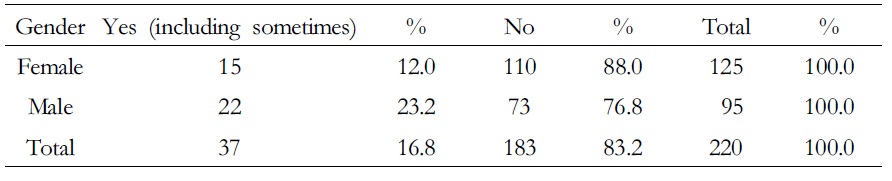

Table 2 (a) looks at the gender pattern in “threatening with fists” in conflict. It shows first that the majority of respondents (83.2%, 183/220) did not practice such behavior in their conflict. Nevertheless, it also shows that such a phenomenon does actually occur between wives and husbands because 16.8 per cent (37/220) of the respondents chose “yes including sometimes.” Considering the gender groups, the results show that the proportions of wives and husbands are quite different. The proportion of males (23.2%, 22/95) is nearly twice than that of females (12%, 15/125), indicating that husbands in this survey say that they practiced such behavior much more than their wives (

‘When there is a conflict between you and your spouse, do you threaten your spouse with your fists?’ (Q25) by gender of respondents:

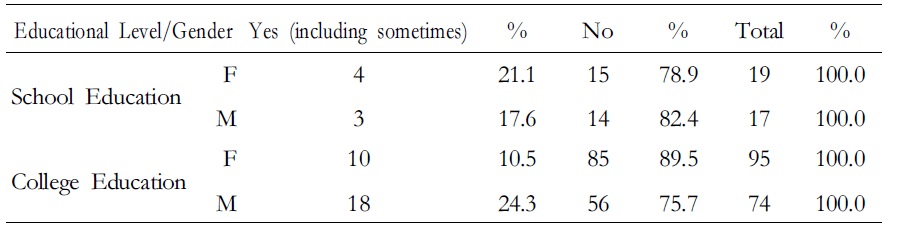

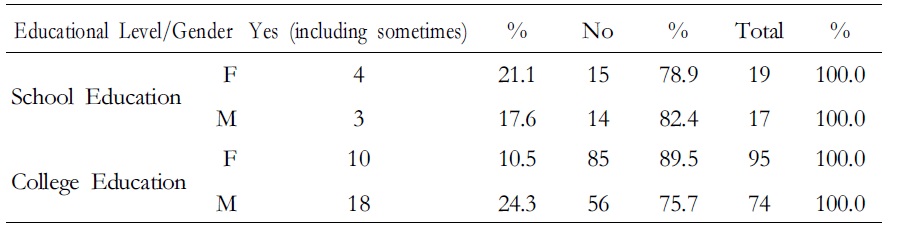

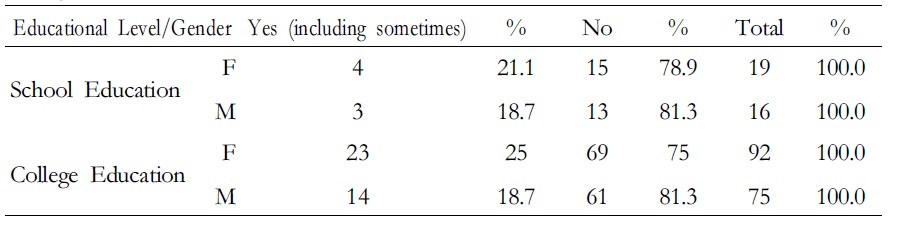

If we look at the two educational groups, ignoring gender, the result in Table 2 (b) shows that there is no significant difference between them in using this behavior. Nineteen point four per cent of the respondents (7/36) with “School Education” reported that they used it to their partners, while 16.6 per cent of the respondents (28/169) with “College Education” reported this, too. However, if considering gender, the pattern is different. Table 2 (b) also shows that there is a slight difference in this behavior between wives and husbands with “School Education”. Twenty-one point one per cent of the female (4/19) respondents said that they used this behavior in a conflict, while 17.6 per cent of the male respondents (3/17) said they did so. The proportion of the former is 3.5 percentage points higher than the latter. But the Chi-Square test indicates that there was no significant difference in using such behavior between husbands and wives (

‘When there is a conflict between you and your spouse, do you threaten with your fists to your spouse?’ (Q23) by gender of respondents with different educational backgrounds

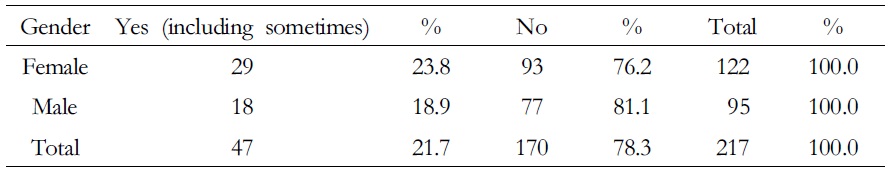

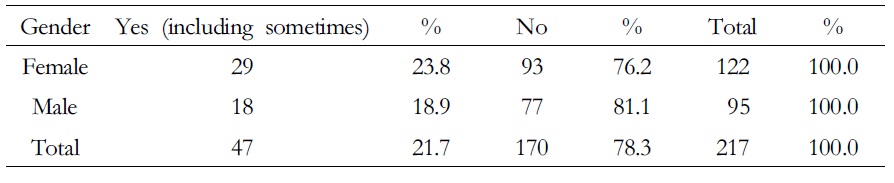

Table 3 (a)6 examines the gender pattern of a non-verbal behavior “stamping of foot” in a conflict. This table shows firstly that behavior such as “stamping of foot” also occurs between some husbands and wives. About one in five of all the respondents say that they use such behavior (21.7%, 47/217). Considering the gender groups, the results show that there is again a difference in such behavior between wives and husbands, this time with more of the women saying that they use such behavior. The proportion of females, in respect to “yes including sometimes”, is 23.8 per cent (29/122), whereas the proportion of males is 18.9 per cent (19/95). The former is 4.9 percentage points higher than the latter. But the Chi-Square test indicates that there was no significant difference in such behavior between wives and husbands (

‘When there is a conflict between you and your spouse, do you stamp your foot to your spouse?’ (Q27) by gender of respondents

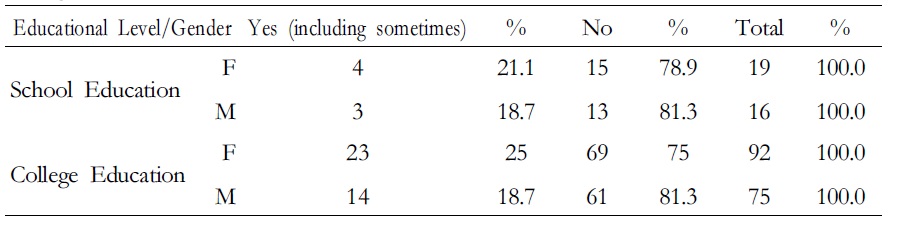

Looking at the educational groups, the result, ignoring gender, shows that the respondents with “School and College Education” practiced “stamping of foot” similarly. The former reported that 20 per cent (7/35) of them used this behavior in a conflict, while 22.2 per cent (37/167) of the latter reported this, too. But looking at gender, there is a difference between wives and husbands in both groups. Wives in both groups (21.1%, 4/19; 25%, 23/92) appeared more likely than husbands (18.7%, 3/16; 18.7%, 14/75) to stamp their foot. But the Chi-Square test indicates that there was no significant difference in such behavior between wives and husbands with the two groups (

‘When there is a conflict between you and your spouse, do you stamp your foot to your spouse?’ (Q23) by gender of respondents with different educational backgrounds

1Work unit. 2In Table 1 (a) and Pie Charts 1 (a & b), the N of valid is 220 (94.8%) and the N of missing is 12 (5.2%) among the 232 samples. 3School Education means the education below Senior School and Secondary Specialized School, namely including Senior School, Secondary Specialized School, Junior School and Primary School. In this survey, there were only 38 respondents at the level of School Education among the total of the 232 samples. Regarding Group ‘School Education’, in Table 1 (b) and Table 2 (b) the N of valid is 36 (94.7%) and the N of missing is two (5.3%), but in Table 3 (b), the N of valid is 35 (92.1%) and the N of missing is three (7.9%). 4College Education means the education over College, namely including the levels of College, Undergraduate and Postgraduate. 5In Table 1 (b) the N of valid is 205 (88.4%) and the N of missing is 27 (11.6%) among the total of the 232 samples. 6In Table 3 (a) the N of valid is 217 (93.5%) and the N of missing is 15 (6.5%) among the 232 samples.

The key findings in this article reveal that both husbands and wives use non-verbal behavior frequently and more or less differently (ignoring the Chi-Square test) in their conflicts. This confirms the claim made by some psychologists that verbal or non-verbal abuse can be used powerfully in reality (Zhang, 2005). In this survey, the respondents reported their use/experience of these non-verbal behaviors (glaring, threatening with fists and stamping of foot), which indicates that they could not forget their experiences, including hurt feelings and other emotional impact. Also, the key findings show the frequency order of such non-verbal behaviors: “glaring” (68.6%, 151/220) is first, “stamping of foot” (21.7%, 47/217) second and “threatening with fists” (16.8%, 37/220) last. The results of the “School Education” group (69.4%, 25/36; 20%, 7/35; 19.4%, 7/36) and the “College Education” group (71.6%, 121/169; 22.2%, 37/167; 16.6%, 28/169) also follow this frequency order. This order shows that couples use the non-verbal behavior “glaring” much frequently in conflict -- probably because it may directly and quickly convey perpetrators’ threat signal to victims.

>

Active’ and ‘Passive’ Non-verbal Behavior

These three non-verbal behaviors have their own features and each plays different roles in the usage. The author in this research therefore classifies these non-verbal behaviors “glaring” and “threatening with fists” as

To the gender pattern, the results show that the husbands were more likely to practice

>

Factors of History, Society and Culture

Historically and socially, the concept ‘men outside but women inside’ has been passed down from generation to generation. Over half of both sexes (actually 61.6% of men and 54.8% of women) still consider this concept to be correct in today’s China (X. Li, 2001; Z. Li & Zuo, 2005; Yi, 2011). Although this Confucian idea was produced a thousand years ago, it has a continuous impact on people’s minds: women should do housework and look after the husband and children, while men are breadwinners, which shows an unequal position between women and men (Gu, 2005). According to a 2001 investigation of the Chinese women’s position, the result shows that the urban women (the majority of them with a full-time job) take an average of 21 hours per week to do to do housework, while men do it only for 8.7 hours (Xia, 2005). According to the newest government investigation (Yi, 2011), 72.7 percent of the married respondents reported that wives, in comparison with husbands, do more housework. On weekends, wives take 240 minutes for rest, while husbands take 297 for rest. These results indicate that wives devote themselves to housework more than husbands. Why is there a difference between them in this? Men occupy a superior position and have more power than women because history and society have empowered them with the special power or privilege (Jackson & Scott, 2002). As Knapp and Hall (2002) suggest, a gesture may forecast the verbalization of a specific idea. Within this context, husbands may be more likely to use

Nevertheless, the results in this survey also suggested something new and interesting. The data at the “School Educated” level shows that the female respondents (21.1%, 4/19) might use “threatening with fists” slightly more than their husbands (17.6%, 3/17) (ignoring the Chi-Square test). This may imply that non-intellectual wives in contemporary society did not mind that they were women who were expected to be “nice women” according to the traditional view. They perhaps dare to struggle for their rights with their husbands in the home. Since their husbands could use this behavior, non-intellectual wives might think that there is no reason why they cannot use it, too. Their behavior breaks with the convention that women/wives are regarded as subordinate. In conflict, they were likely to use such

Further, both intellectual and non-intellectual wives, as described in the author’s interviews, who suffered psychological violence, said that their husbands behaved maliciously in conflict (no husbands talked about this). Noticeably, because of the author’s inexperience in conducting interviews, she regrettably did not elicit more specific descriptions or definitions of such behaviors, in particular of non-verbal behavior. Nevertheless, although the participants did not specifically describe non-verbal behavior, it may be inferred that the malicious action by husbands more or less included the

Through this analysis and discussion, it can be found that the concept “men are superior to women” is still rooted in Chinese people’s minds. Socially, people identify men and women with a gendered understanding of women’s position in family and society as being subordinate (Jackson & Scott, 1996). This identification focuses not on their biology or nature, but is a purely social definition (Jackson & Scott, 2002; Lerner, 1986). As a result, the term “gender” is produced in our life, which is unrelated to “sex”. These two terms are quite different because gender is seen as femininity and masculinity, while sex means female and male. The concept “gender” permeates the whole society, including politics, economy, policy, law, education, family, employment, medicine, welfare, etc. and impacts on people’s lives, in particular on the lives of women. For instance, in education, according to the national statistics, two hundred and twenty-three million people over 12 years old were illiterate and semi-illiterate in China. Among them, women comprised 70 per cent (one hundred and fifty-six million). As for the women who were not illiterate, their educational level was considerably lower. Women at the level of junior school and over junior school were 38 per cent of the total population at the same educational level, but only 1.5 per cent of women were at the post-graduate level (Du, 2005).

This education gap between men and women exists because of the traditional concept that “a woman without knowledge is seen as a virtuous person”, which means that women should not have any knowledge and should only follow their “innate natures” by looking after men. According to the old view, this is the only suitable role for women in family and society. However, this concept is still widely accepted today, particularly in backward areas (Du, 2005). For example, there is a difference between rural women and rural men in level of education. The proportion of rural women at the educational level over junior school was 42.3 per cent, which was 20.8 percentage points lower than that of rural men. Among this female group, 58.8 per cent of women accepted the normal education below primary school, which was 21.9 percentage points higher than that of men. The proportion of illiterate women was 13.6 per cent, which was 9.6 percentage points higher than that of men. This indicates that rural women are inferior to men in education, which directly reveals their low position in society (Wu, Wang, & Li, 2009) and also impacts on their position in the family. This concept hinders the development of women, and they, of course, easily experience psychological domestic violence by their husbands. Rationally considered, how can women without knowledge and working as housewives who are regarded as inferior to men in the home be more likely to choose

The existence of gender inequality reflects that society truly does not respect women. In reality, women may not enjoy a right of life, study, and work that is equal to men’s. For example, in employment, there is no cause for optimism because women have more difficultly in finding jobs than men. In a report of female college employment by ACWF, 56.7 per cent of female college students in interviews said that there was less opportunity for them in the process of seeking jobs than for male students. Ninety-one per cent of female students, when looking for jobs, felt that some staff held gender prejudice (Du, 2005). Such prejudice is readily apparently in many job advertisements: men first for this job within the context of the emphasis on equality between men and women in society (X. Li & R. Zhao, 1999; X. Wang, 2011). Why are such job advertisements prevalent in the supposedly egalitarian society to people’s vision or to society? Why do female college students or women look for jobs difficultly? Some people (mainly men) who are in charge of units or companies think that there will be loss of profits if they employ young women who will soon be married and give birth to (Q. Yang, 2005). The people holding this view are going against nature and wrongly refusing to provide chances for young women to work. Giving birth to a child is not a shortcoming for women because men and women should bear this responsibility together for the sake of society as a whole. Society, in the light of women’s biological role, should be concerned about women fairly because they play a special role for humankind.

Since 1949, the policy of retirement in China has not been amended yet and sticks to convention, which may not be appropriate for social development, including for women and men (Z. Ye, 2011). Such policy has hindered the development of society. This has recently been a heated topic for discussion and research in China (Yu, 2011). In the light of this research and discussion, why has the policy not been amended? This may be because decision-makers more or less hold the concept “men outside but woman inside”. Actually, they approve “men are superior to women” in their mind reflexively. As a result, they have made a policy which does not conform to human rights. The retirement age is higher for men (60 years) than it is for women (55 years), which indicates that women cannot enjoy the right of the same retirement age as men (Hershatter, 2007; Mo, 2004; Ye, 2008). Noticeably, women may always be hurt socially because they were the first to be affected in the labor market. For example, during the period of economic reform in China, women are the first to be laid off (

These old concepts and inappropriate policies in relation to gender difference expand the wage gap between men and women and determine how their respective labor is perceived. Within this context, men’s work usually is economically and socially valued. In contrast, women’s housework is usually not valued in family and society. In other words, the value of women’s household management is never calculated in people’s minds and never seen as a contribution to family and society. For example, one female individual in the author’s interviews, who gave up her job and did housework and looked after their baby daughter in order to support her husbands, suffered domestic violence at his hands. Her husband said that he was breadwinner for the family so that he could abuse her. Importantly, he neglected how he did his job and achieved success if it had not been for his wife’s support? Socially, the inequality of labor division empowers men to dominate women, apparently legitimately. As a result, the position of women, in comparison with men, is inferior in family and society (Tang, Wong, & Cheung, 2002), while men have power over women. If deeply looking at this, it may be seen that such gender inequality reflects a pervasive ideology in which women are not respected and are looked down upon socially. Thus there is no doubt about why women are the main victims both specifically in these

As far as China is concerned, it is an old and civilized country. Its development has created rich and various cultures. As Orum (2001) illustrates, culture is a historic and objective phenomenon because it has been passed on from generation to generation. Moreover culture becomes a strong force to restrain people’s daily life and the development of history and society. This is reflected in a series of concepts such as “men outside but women inside” and “men are superior to women” and so on, which have spreads far and wide among the masses in China for many and many years, and are widely accepted even today. Take gender inequalities within families as an example. In China, if a son is of marriageable age, parents say that their son will take a wife (

Thus, the problem of sex ratio at birth occurs very prominently in China because of the gender inequality between men and women. In particular, when the policy “one family, one child” has started to be implemented mainly in the urban areas, some of the urban Chinese couples more expect/want to have a boy rather than a girl. Moreover couples in the rural areas want to have more boys, although they are allowed to have one more child if the first baby is a girl. This again reflects the fact that people who have power to make policy and law cling to the concept “men are superior to women” for why else would rural couples be given the privilege of having a second baby if the first one is a girl? Within this context, many illegal medical agencies have been established and, for money, help those who want to have a boy to identify the sex of the fetus. If the fetus is a girl, the baby will be aborted. By the sixth national population census, the ratio of men to women (100) is 105.2. Although this ratio has declined 1.54 in comparison with the fifth national population census (Yu, 2011), the imbalanced sex ratio is still a key issue for China. Apparently, men and women, boys and girls, and even male and female fetuses, do not share similar life-chances culturally and socially (Hanmer, 2000). Women’s position is lower than men’s in marriage and family as well as in society.

Based on Confucian ideas, in the family, a model wife will be praised by her husband and in-laws and admired by her neighbors, friends and her husband’s colleagues for being genial and devoted. She will not express any views on any issues or argue with her husband, and she will tolerate anything her husband does to her, including domestic violence. Some of the interview cases are cases in point. A few female individuals said that their husbands required them not to argue with them when a conflict occurred between them. Their husbands see themselves as the center in the home and act as a patriarch to their wives. The results of the author’s survey showed that wives were more likely to use

Culturally, during the process of women’s growth, they are usually educated as to how to become a good girl or wife. For example, they are instructed to play a series of mild games such as jump rope and hopscotch, and so on, which differ much from the games played by boys, such as sticks and guns, “red” and “blue” armies, fighting, and so on. From these different activities, we can see that girls’ games less frequently involve winners or losers or the giving and taking of orders, while boys’ games generally result in winners and losers and involve elaborating rules that are frequently the subject of arguments. Boys’ behavior is more challenging than girls’ and it is apparent that relative power seems to be an important part in boys’ sub-cultures but much less so in girls’ (Q. Ye, 2011a). Thus, this is why wives (23.8%, 29/122) are more likely to choose

Since the economic reform, Chinese people’s view of marriage has been changing, with the result that young men and women are finding it increasingly difficult to find partners. Today’s young women influenced by consumerist culture, praise highly the concept of “marrying a person who has power and wealth rather than succeeding in study”. They express their “money worship” with clever-sounding words, for example, “It is better to cry in a BMW than to smile on a bike.” Thus, young men in their twenties and thirties, at the beginning of their careers, are faced with the dilemma of having to satisfy women who hold such values if they want to get married. Moreover, cases have emerged in an endless stream in China of young women dependent on rich older men and acting as concubines (

This study, although it is a very small piece of the author’s entire research, has shown that different non-verbal behaviors (

This study differs from the previous studies because it explored the specific forms of psychological domestic violence, which are normally ignored in research but actually have a powerful impact on victims (Goldstein, 2002). In particular, this study provided the key findings not only in relation to both husbands and wives, but also to couples at intellectual and non-intellectual levels, which was less emphasized in the previous studies. This study also introduces something new. First, wives just as well as husbands used non-verbal behavior (particularly

This study is just the beginning of the author’s research career in the field of domestic violence. Thus, it is hard to avoid limitations in some aspects. For example, one limitation involved research design. The questions in relation to the non-verbal behaviors “glaring”, “threatening with fists”, and “stamping of foot” were posed in a questionnaire, with the result that these behaviors were not described in detail by the individuals in the depth-interview because the author lacked experience in asking follow-up questions when the subjects roughly narrated their sufferings, but luckily data was obtained regarding other non-verbal behaviors, e.g. non-communication, indifference, and silence, in both survey and qualitative interview. This therefore necessitated that this article discuss these three non-verbal behaviors without direct comparison with interview data. Another limitation involves the non-intellectual group (School Education). The majority of the survey data was collected mainly in schools, universities, and hospitals, which resulted in the number of non-intellectual respondents being quite small in comparison with the intellectual respondents. This therefore may lead readers to regret the lack of more powerful and persuasive discussion in this article, but this article could only provide relative results (not absolute ones) when discussing non-verbal behavior used/experienced by intellectual and nonintellectual families. The author should therefore carefully consider the choice of research sites in the future Nevertheless, this research arrived at its aims, despite these limitations.

Finally, the author acknowledges that the whole society should do more in order to eliminate gender inequality and domestic violence. In particular, education is a key point for people in China. For instance, should a course against domestic violence be officially offered in schools and universities officially? Such a course may help students to understand the importance of stopping domestic violence and of eliminating gender inequality at an early age. People need to be aware that women should enjoy the right of life, study and work same as men. Exploration of domestic violence is an arduous task. All people should contribute themselves to this task for the sake of beautiful life in the future.