The aesthetic attitude, in general or in particular, represented in matters of taste through aesthetic ideas and value judgments postulates a certain literary logic. And this literary logic reveals itself a sense of morality, philosophy, or moral aesthetic consciousness through the moments of act and thought demonstrated in the characters invented in literary works. Henry James, among many others, offers a very special cultural paradigm for transnational argument because of his diverse ways of shaping transatlantic relations in terms of aesthetic consciousness. And this international paradigm produced varied expressions referring to Henry James as “an American expatriate,” “an Anglicized American artist,” “a Europeanized aesthete,” “a cosmopolitan intelligence,” “a bohemian cosmopolitan” to designate his literary career and its characteristics shaped in Europe. The implications of these expressions — absence, déraciné, ubiquity, or transformation—are worth considering since they are relevant to the question of James’s cultural stance challenged by the arguments for national belonging problematized by the critics for more than a hundred years. Such expressions can resonate with

James’s temperament of mind, far from being always identified with shared values within an ideological framework, never avoided friction with fixed ideas but rather absorbed it fully for another friction which intervenes in his house of fiction. My question arises here regarding his cultural belonging or dislocation: where is

In this essay, I’d like to define

To start with the first argument, I’ll analyze some essential aspects of aesthetic consciousness of his characters to postulate a persona capable of theorizing James’s aestheticism conditioned by the transatlantic context. For the second argument, I’ll examine how the persona functions in formulating a proper cultural stance of James’s aesthetic consciousness in transatlantic perspective to illuminate the way of how Jamesian individuality reflects the American mind.

This process of theorizing a place of James’s own will lead, I hope, to our discovering James’s ultimate destination on the assumption that it’ll prove or create a certain “sympathetic justice” for his humanist aestheticism, a Jamesian absolute morality.

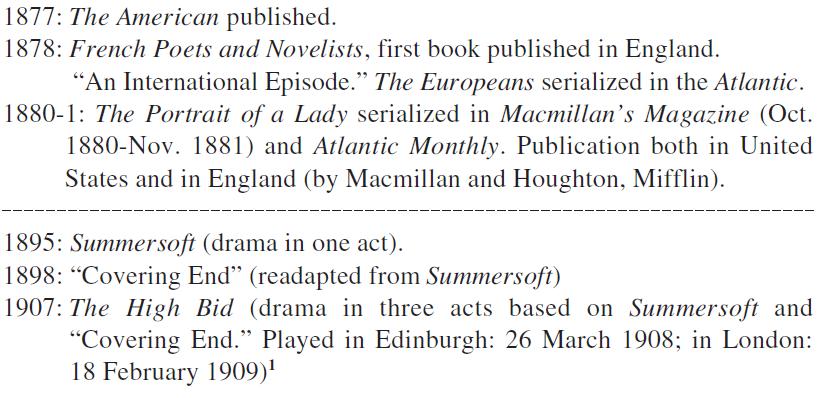

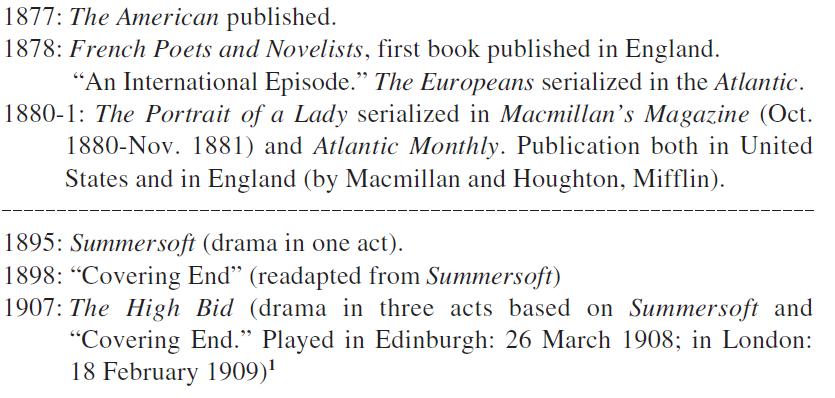

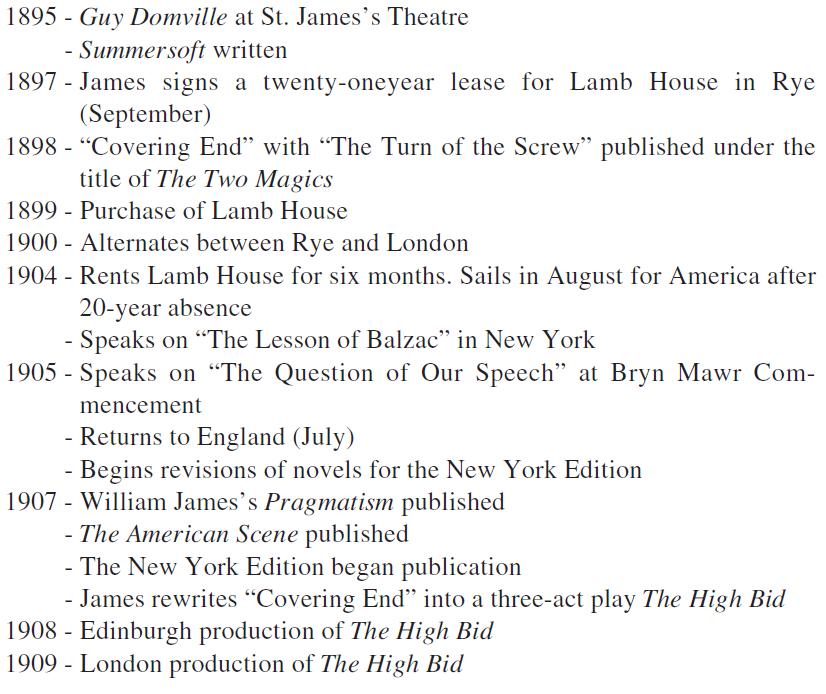

One of the most natural and poignant questions regarding James’s transatlantic position might be the will to combine two worlds, the old and the new, which is represented in the ways of shaping connections with cultural heritage. To start our argument with the character’s free will like Newman’s, Isabel Archer’s and Mrs. Gracedew’s, let’s make a brief chronology that will help us to assess the ways to look at James’s literary position regarding its

[Table 1.] From The American to The High Bid

From The American to The High Bid

We can figure out one of the features of James’s

Newman’s interest in Claire doesn’t lie in her own human mind but in her appropriateness, coming up to the high mark, to his own mise-enscène of a well-made plot of life, of cultural combination. Thus, consequently the case with Claire and Newman ends by being severed and positioned respectively in his or her own cisatlantic world. Isabel Archer has a strong confidence in her aesthetic consciousness, in her evaluation and her judgement. And the whole process of marriage is justified from her own moral aesthetic vision of cultural combination of the old and new worlds, but goes wrong and distorted by Osmond’s hidden purpose of the marriage with Isabel.

1James’s conception of the character Mrs. Gracedew goes back to 1895 (or earlier) when she first appeared in Summersoft. The play Summersoft has not been printed during his life while “Covering End” “a close paraphrase of it [Summersoft] in story form” was printed in The Two Magics in 1898, and readapted into a drama The High Bid in 1907.

III. Henry James at Work with Mrs. Gracedew

Take a closer look at the initial conception of Mrs. Gracedew, the heroine of our concern, firstly postulated above as a persona capable of theorizing James’s aestheticism:

James’s American woman, “intensely American in temperament . . . but with an imagination kindling with her new contact with the presence of a

An American woman in “the affairs of an old English race”—this situation would give a clue for our argument on the questions of “How she steps in” and how this affects American mind and her aesthetic consciousness. Given the situation and perspective likewise, I’ll examine the meaning of her “stepping in” by analyzing its relationship with James’s own cultural position between the old and new worlds to argue her being as a persona capable of theorizing James’s aestheticism.

Mrs. Gracedew is a persona who “must represent the idea of attachment to the past, of romance, of history, continuity and conservatism” with “an imagination kindling with her new contact with the presence of

At any rate, then, what is the meaning of her personal aesthetic consciousness validated by its social and historical context? Carlson argues about the question of sacrifice by bringing Rowe’s argument of it3 as “one of the main actions Jamesian women can undertake” focusing upon the sacrifice elevated into salvation in James’s works (Carlson 413). What’s more important for our topic is to look at the ways of how James delineates sacrifice or salvation through woman in action in a specifically transatlantic condition since there’s a certain radical growth of James’s vision of American mind “beyond our Anglo-Saxon ken” (Dwight 441).

The action is represented through her manner, especially through her speech of value judgment as well as her knowledge and historical consciousness of cultural heritage. Henry James seems to have given her a real power of speech dramatically persuasive in the end even though Mrs. Elliott, who played the role of Mrs. Gracedew in

Gertrude Elliott felt that the audience did not feel with her when she delivered her great appeal for the preservation of the past to Captain Yule. That’s the reason why she wrote to James to render Mrs. Gracedew’s point of view unconvincing to the audience:

Henry James’s position vis-a-vis Gertrude Elliott’s regarding a possible modification is so “adamant.”

To James, the subject must be treated

It’s “the Ages,” “the brave centuries” who have trusted us to keep humanity or to share the house with us all. It’s the power of the past personified dynamically to arrive at the concept of utility where we might recognize a spatio-temporal harmony, the harmony of human house of all ages with humanity itself to share with all.

It seems to be that the past evoked by the discourse of Mrs. Gracedew illuminates a certain philosophical basis of Henry James: a certain utilitarian concept of the art of the past dynamized. That’s how Mrs. Gracedew’s speech or dialogue embodies a dramatic logic what James hoped to construct “on Mrs. Gracedew’s grounds and in Mrs. Gracedew’s spirit.”5

Then, what could be the real meaning of the “high bid” realized by Mrs. Gracedew with her passion by stepping in to the English social dilemma?

It seems to be that the high bid of Summersoft or Covering End is closely related to a very special mind of the place or to a place of the mind: the human house as the hereditary property of “all Ages” cannot be bargained over the price of it with anyone of personal interest. It should keep its place as “the Ages” have trusted them. That’s the reason why Mrs. Gracedew is

The dialogue “for an act of salvation” can be paralled with James’s speech on “The Question of Our Speech” for American women of the period. The dialogue of Mrs. Gracedew and the speech of James, periodically close to each other, emphasized by its meaningful importance upon the speech

2James shows “a love interest” in his Notebooks. However, it does not serve as a momentum nor as a purpose of cultural combination, but it’s suggested at the end of the play. 3Rowe argues that “Facing a potentially angry audience at the very end, Olive offers herself sacrificially in the place of Verena, who has been swept away, ‘saved,’ by that imitation cavalier, the belated and displaced Southern gentleman Basil Ransom.” This “activism” as “a sacrifice of ‘taste’” seems “the only ‘act’ available for such women in James, which may explain further why James has prompted such ambivalent responses from feminist critics” (Rowe 92). 4See also SS. 537; CE. 301-02. 5I brought this above argument regarding human home and dramatic logic from Roman (Kim 460-61), using the same quotations, to extend it for another argument about the speech of American woman in terms of cultural interaction in a transatlantic context.

IV. A Parallel as Interactive Power between Mrs. Gracedew and Henry James

Mrs. Gracedew, existing in different literary forms, might have been conceived to embody the question of speech since James’s literary itineraries of the 1890’s and 1900’s offer a logical context for the importance of woman’s speech of the period in America. It seems to be that the question of speech is consistently pursued and emphasized through the dialogues of Mrs. Gracedew in three different versions of

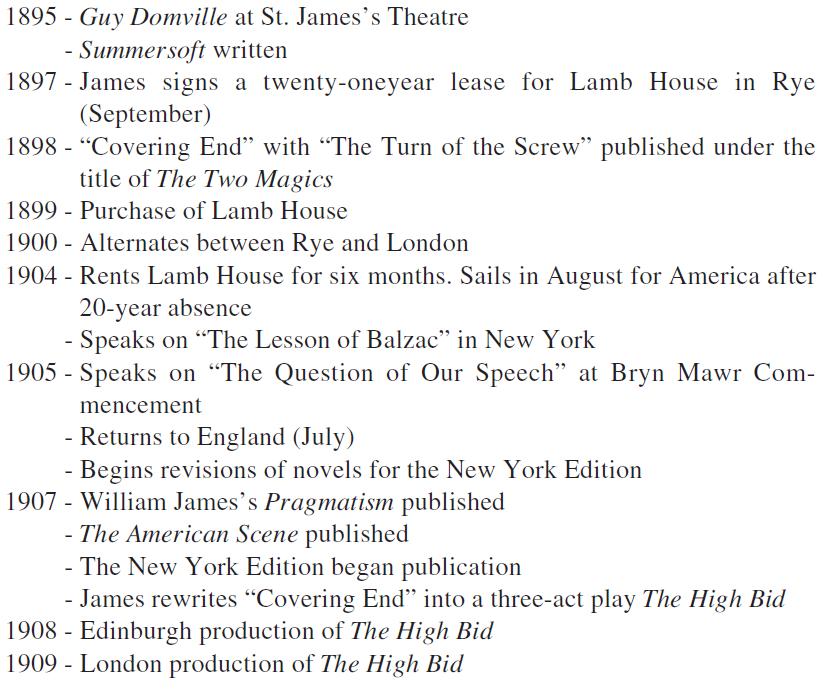

Thus, the question must be asked as to the way of how to characterize this parallel between James’s specifically American commitment and Mrs. Gracedew’s dramatic role as an American woman in action in England? Let’s look at the chronology (Table 1) again to examine the parallel from a different angle of view trying to make a new chronology (Table 2) from 1895, the year of writing

[Table 2.] Henry James from 1895 to 1907

Henry James from 1895 to 1907

Table 2 shows a very peculiar concurrence between his writing activities and his actual life bringing different aspects to the fore: if James used an English house as a motif for social dilemma in

Mrs. Gracedew’s stepping in executed by positioning herself in modern transnational context manifests her will to preserve the place as it had been preserved as a

Meanwhile, this interest in London does not result in the same appreciation as that of a very dynamic one morally executed by an American woman to save the home of the human race. James bestows such a convinced competence on her by giving her a speech of practical ethics as an American woman with a good cause. Therefore the gracious power of Mrs. Gracedew is not something for purchasing or acquiring to carry it away, to appropriate it for her own interest but something for preserving it, to make it

Here are two interesting anecdotes to be considered for the argument above regarding art and economy in view of aesthetic consciousness and its practical ethics: the first one is the British purchase of a painting by Veronese which J. Ruskin defended as a good bargain; the second one is about the American purchase of the “Catlin’s Indian Collection” as national duty manifested by the 1849 speech of Webster.7 James was quite cynical about Ruskin’s focus on the value making of the British purchase in terms of economic viewpoint. Dimock argues their [Ruskin and James] “difference” as “a different understanding of what constitutes ‘economy’ and ‘waste’ when art changes hands, when a powerful nation takes it upon itself to acquire beautiful objects from abroad” (Dimock 97). James’s attitude seems to reflect the sentiment or cultural consciousness

There is a possible parallel between Mrs. Gracedew’s speech and Webster’s: a parallel between Webster’s “

As is generally known, the question of the search for an American voice to awaken national consciousness was prevailingly accentuated through the 19th century, more specifically during the Romantic period of the American Renaissance. James’s idea about the American speech or American voice can be aligned with this tradition of continuous pursuit of an American self manifested long time ago by R. W. Emerson in his “The Poet.” If Emerson said that “For all men live by truth, and stand in need of expression. . . . The man is only half himself, the other half is his expression” (Emerson 243), calling upon American metres to deal with “its ample geography” which “dazzles the imagination” (262), James raised the question of “our speech” to the American women expressing his feelings on “our” civilization “strikingly

If Jessica Berman points out that “James’s writings from his 1904-5 American journey bring this redefinition of American womanhood into the international arena, renewing and expanding his excursion into cosmopolitanism by arguing for its continued enunciation” (Berman 54), the initial conception of the persona of Mrs. Gracedew for

Examine again James’s literary itinerary of the period in question (see Table 2) focusing upon the details of the parallel between the persona of Mrs. Gracedew and Henry James from a different angle of view. Henry James, preparing the play

If James “was to forward the cause of civilization: his very experience of the over-riding female had created permanent damage within himself in his relations with women: and in that marvellous way in which nature insists on compensations and solutions, his constant effort to repair the damage, to understand what had gone wrong, gave him the necessary distance and aloofness . . . that enabled him, of all novelists, to understand the writing of

With Mrs. Gracedew, a persona who creates a culture of commitment in different cultural settings, social and cultural commitment is no more a question of appropriating but of preserving cultural values. And her performance, it is exactly like a poetic drama profound and sympathetic in its beautifully strong human voice. William James would have valued it, if he knew Henry James’s American heroine Mrs. Gracedew, as “sympathetic justice” (

6P. Lubbock refers to “Covering End” as one-act play “disguised as a short story” (LHJ II: 6). It’s quite possible to say likewise since James himself refers to it as “the little one-act play presented as a ‘tale’ at the end of the volume of the Two Magics” (Henry James to William James’s son, Henry. April 3rd, 1908. LHJ II: 96). “The Turn of the Screw” and “Covering End” were published under the title of Two Magics in London and New York in 1898. 7I discussed about Catlin’s exhibition at the Louvre Museum and its historical meaning in terms of cultural exchange between America and France to make American cultural consciousness come to the fore by bringing Webster’s historical stance itself as “an important public act” of cultural preservation of national heritage” (“Changing Aspects of Cultural Exchange between France and the United States: American Art and the Louvre Museum” 225). I use the argument here to assess a parallel to be contextualized in another argument on aesthetic consciousness and its practical ethics. 8Catlin said that he “made a collection of more than 600 portraits of Indians and paintings illustrating their modes of life” and he “made an Exhibition of the same in New York, in Paris, and in London. That Exhibition was very popular. [. . .] At that time, however, the Senate of the United States was considering a Bill for the purchase of my collection, for the sum of 65,000 dollars. [. . .] Messrs. Webster, Seward, Foote, and the other Federal members were in favour of the appropriation, and voted for it; and the democratic members voted against it” (Ross 5). 9I made a long argument about these three works interpreting this case as a very special, unique one not only in terms of genre criticism but also on its significance in the literary theatre history (Roman 2, Chapter V).

V. “the knower as spectator” and “the knower as actor”

Henry James began to get the question of the old and new worlds into shape by composing conflicting relationships in the Euro-American transatlantic conditions. But, as if the division of the literary genres gives a comparatively convenient framework for literary discourses, cultural differences between two worlds created a convenient cultural distinction for his moral aesthetic discourse, finally attaining to a certain synthesis for a certain humanist aestheticism. For this kind of sympathetic synthesis James created a subjectivity, an American female being gifted with individuality who transcends individual, national distinctions. A question might be raised: why is this interconnecting role, the role to eliminate a certain spatio-temporal specification or separateness given to a female character? Doesn’t this reflect James’s own desire to strengthen his literary position within the Euro-American conditions? We can get a fair insight into James’s literary sociology of woman covertly connected to his own position in the transatlantic circumstances by considering James’s own position as a minor in Europe or in England being comparable to that of women in the nineteenth century patriarchal society.

The subject capable of connecting different cultural backgrounds and social conditions surpasses individual, social, national values of distinctions and meets with transatlantic requirements of a modern cooperation expanding human mind into a universal whole to share. Even though James said he was “deadly weary of the whole ‘international’ state of mind─so that I ache, at times, with fatigue at the way it is constantly forced upon one as a sort of virtue or obligation” (

VI. Conclusion: A Dialectic of “a big AngloSaxon total”

Mrs. Gracedew, “intensely American in temperament,” should represent “the conservative element” stepping in to the crisis of English social heritage. Hence, the germ of the reversal in that crisis is inherent in her character. It’s the role of clearing up and salvation to be played out by her

America and England are of two different cultures but are also two of the same Anglo-American macro-culture. If the British have a cultural heritage in consistency and continuity, the Americans formed a new culture through ruptures and variations of the consistency. But it’s Mrs. Gracedew, the American, who

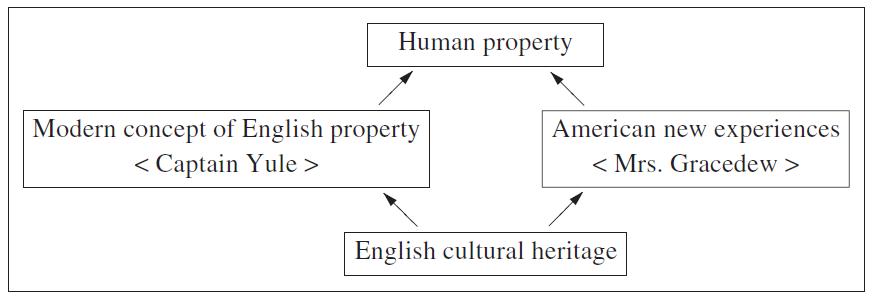

Mrs. Gracedew is historically contextualized: she’s not the person who grew up in English society but an American who might have come out of the very tradition and at the same time who must have completely new experiences. Her cultural stance can be explained by three dialectical stages of development: a) thesis: English society as static continuity; b) antithesis: problematic situation of the society and its question of sustainability represented by Captain Yule’s modern concept of English property and Mrs. Gracedew’s dynamic view of the static continuity; c) synthesis: English cultural heritage turned into

Even though the theme of salvation is conditioned specifically in the transatlantic context, the meaning of it expands itself towards universal humanity through Mrs. Gracedew’s purely aesthetic vision. That’s how James solves the question of transatlantic separateness reconciling the vision of the new and the old, making them coexist in the universal human property. Here comes a poetic truth of her moral aesthetic capacity challenging to the social dilemma to meet with aesthetic sense of historical mind. It seems to be that James feels oneness or sameness with Mrs. Gracedew since her aesthetic mind and ethical practice proved the truth of it. If Stowe and Margaret Fuller “produced themselves . . . as female transatlantic subjects on the literary, social, and political scene” (Stowe 160), as William Stowe argues in his “Transatlantic Subjects,” James created Mrs. Gracedew, an American character, as a female transatlantic subject on the English cultural social scene which might be her other frontier.

The question of woman’s speech to James must have been rather a national exigency for modern America to promote a certain cultural development keeping its transatlantic relationship with Europe, especially with England as people of “our consecrated English speech” (

Here’s how to view James’s identity consciousness: a sense of unity relying on “a big AngloSaxon total” rather than on “the English & American worlds.” And literature which “affords a magnificent arm” for treating the life of the two countries “as simply different chapters of the same general subject” can change and reshape people’s perspectives on things. And another question arises: how to locate this consciousness of “a big AngloSaxon total” when we consider his cultural stance as cosmopolitan or universal? Given the anglophone Atlantic, James’s intercultural conflicts seem to reflect, or conform to the Atlantic history which could be defined as: both (the United Kingdom and the United States) “can be seen in retrospect to have conjoined statehood with a fictive nationalism” (Armitage 20). And James’s mind seems to reside in such a “fictive” nation of “conjoined statehood,” or rather somewhere in between the transatlantic cultural perspectives where the history of cultural heritage continues, or continuously convertible, consequently, his artistic mind can become

American mind in a very special transatlantic cultural context to be a universal one—this is a unique American position or temperament with

This metaphor of literary mind practiced and realized in the form of humanity from transatlantic perspective brings Henry James into a universal arena in which he deserves to have us to define his “poetic justice” as “sympathetic justice” of humanist aestheticism.

10The fact that there is no space between two parts (“AngloSaxon”) in the Correspondence led me to examine James’s letter (MS_Am_1094_(2039) conserved in the Houghton Library, Harvard University. But I didn’t know whether there was a hyphen hidden between the two parts or not; certainly it’s well-hidden if it’s there. Such an ambiguity made me conclude that the hyphen is underneath the o, implied or purposefully elided. I am grateful to Susan Halpert at the Houghton Library for helping me verify the above quotation in the manuscript.