The Northern Limit Line (NLL), a de facto maritime border between the Republic of Korea (ROK or South Korea) and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK or North Korea), has been one of the most potent flashpoints in Northeast Asia. The sinking of a South Korean navy corvette (

As a way to deal with the NLL issue, former South Korean President Roh Moo-hyun (February 2003-February 2008) initiated a major desecuritizing approach fundamentally different from those of the previous South Korean administrations. The “Initiative of Special Peace and Cooperation Zone in the West Sea” was, albeit unsuccessful, a political bid for mitigating and eventually ending the ceaseless spiral of enmity and security dilemma between the two Koreas. Roh even attempted to renounce the notion of the NLL as a “territorial border” against the entrenched notion of territoriality in South Korean society. Roh’s security policy was quite difficult to comprehend when viewed from a rationalist perspective championing

What brought Roh to choose an initiative that could weaken South Korea’s national security and embolden its “main enemy,” North Korea, regarding the jurisdiction on the waters near the NLL? Was it a shift of policies stemming from any notable change in power, institutions, ideas, or identities? What implications does Roh’s approach have for regional security in Northeast Asia? Why was Roh’s approach to the NLL entanglement frustrated?

I aim to answer these questions by using the Copenhagen School’s (CoS) Regional Security Complex (RSC) theory. The RSC theory reflects the real concerns of policymakers and provides a practical framework for security analysis. I start from the assumption that the Northeast Asian RSC, including the Korean problem, is not “out there” in a permanent state, but that it can also be reconstructed by agents. Roh’s “bold” attempt against the NLL issue also can be reviewed in the context of a process of desecuritization of threats in the dynamics of the Northeast Asian RSC.

Beginning with a closer look at the RSC theory and its relevance as a tool for studying security practice in Northeast Asia, this study highlights the pivotal position of the Korean problem in forming the Northeast Asian RSC, lays out a few propositions and some operational hypotheses concerned with the (de)securitization process in RSC, and applies the analytical framework of (de)securitization to the NLL issue as well as the dynamics of the Northeast Asian RSC. In so doing, this study emphasizes the importance of domestic political leadership in desecuritizing threats, which can lead to the evolution of RSC.

Ⅱ. Dynamics of the Northeast Asian RSC

Given the scarcity of multilateral organizations for regional cooperation and the realist penchant of the states in Northeast Asia, neorealism has often been used to analyze the international relations in the region. However, the RSC theory, which does not contradict the realist notions of power politics nor accommodate the constructivist conceptions of perceptions and discourses, offers a more nuanced approach in analyzing a wider range of security issues. Furthermore, it projects Northeast Asia as one integral unit.

1. Security Landscape from the RSC Perspective

Unlike neorealism, the RSC theory is not a system-level theory, but rather a medium-range theory. To picture “security” more accurately, regional and global levels must be understood independently, as must the interaction between them. “The regional level is where the extremes of national and global security interplay, and where most of the action occurs.”1) The central idea of the RSC theory is that because most threats travel most easily over short distances, security interdependence is normally patterned into regionally based clusters, known as security complexes.

In addition to emphasizing the regional level, the RSC theory stands apart from neorealism by incorporating social construction in its approach, thereby recognizing the potential for change in security dynamics. From the neorealist perspective, states operate in an anarchical system where each state must concentrate on strengthening its security capabilities even if this induces insecurity for others. The RSC theory does not seriously dispute the anarchical structure, but assumes that within this structure, the essential character of RSC is defined by a couple of independent variables: the distribution of power and patterns of amity/enmity.2)

However, in their pioneering work on the RSC theory, Buzan and Wæver do not consider Northeast Asia as a RSC. They do not deny that Northeast Asia conforms to their basic definition of RSC, as “a set of units whose major processes of (de)securitization, or both are so interlinked that their security problems cannot reasonably be analyzed or resolved apart from one another.”3) However, they argue that in the mid-1990s Northeast Asia and Southeast Asia began to merge into a single RSC, within which Northeast Asia formed a subregional complex. According to them, with the establishment of the ASEAN Regional Forum and Vietnam’s ASEAN membership in the mid-1990s, the point was reached at which the interregional dynamics of East Asia overrode the regional ones.4)

Yet, Northeast Asia is also very much defined as a single RSC by its own characteristics. First, considering its turbulent history, one could assert that patterns of amity/enmity play a significant role in Northeast Asian security dynamics. Nowhere is the effect of patterns of enmity more obvious than between the two Koreas, which for over six decades have interpreted their history differently and refused to formally recognize the legitimacy of one another. Moreover, concerns of a traditional structure continue to trouble this region, including cross-straits tension between China and Taiwan, and the ongoing nationalistic disputes over the historical legacy of the Pacific War and Japan’s colonial past. In contrast, Confucianism and other cultural and historical links feature some dynamics of amity in the region.

Second, material issues concerning the distribution of power also predominate in Northeast Asia. In this context, China-US relations are critical, partly because they influence the nature of the relationship between China and Japan. This triangular relationship constitutes the prevalent dynamics of the Northeast Asian RSC. However, the dynamics of this triangle and each of its components, including the future role of China in the region, remain a source of uncertainty. Moreover, more tangible concerns that affect the security in Northeast Asia include several unsettled territorial and maritime issues, including the NLL entanglement. These unresolved problems clearly have an impact on all agents of this region as well as on the patterns of security interdependence in the Northeast Asian RSC.

Meanwhile, Northeast Asia is not just a geographical area because of the difficulty in distinguishing between regional and global levels. What is at issue here is whether the United States belongs to the Northeast Asian RSC. In CoS’s scheme, the United States is not a member of the East Asian complex.5) Instead, it is treated in terms of penetration or overlay. Actually, the United States is a major state having a high degree of security interaction with the Northeast Asian states. This mechanism occurs when “outside powers make security alignments with states within an RSC.”6)

2. The Korean Question as a “Gordian Knot” in the Northeast Asian RSC

When we apply CoS’s own definition of security complexes, Northeast Asia itself can also be qualified as a single RSC. In particular, the “Korean question” brings together the key regional powers to mutually form a regional security dynamics of amity/enmity.

Situated where the greater powers intersect, the Korean Peninsula has played a pivotal role in the politics of Northeast Asia. Historically perceived by its neighbors as both an opportunity and a threat,7) the peninsula is strategically positioned where shifts in the regional balance of power are played out. On several occasions, conflicts of interests between powers seeking to influence or dominate the peninsula led to war. In addition, any change in the peninsula has the potential to alter the regional order. Therefore, as the level of uncertainty in the peninsula has grown, greater powers also reinforced their level of engagement. In this respect, the role of China and the United States in the stabilization process of the peninsula remains central,8) while the development of the two powers’ security practices and foreign policies is itself an issue of regional and global interest.

As one of the main crisis spots, North Korea has been a key variable in the Northeast Asian RSC. Because of the dire state of North Korea’s economy, inter-Korean reunification under current circumstances would mean absorption of the North by the South, which is one reason as to why the North is trying to develop nuclear weapons. Not only is the problem of North Korea a constant source of concern for the Northeast Asian RSC, it has also created a major fault line that divides opinions within South Korean society.

Arguably, the Korean question is one of the most intractable problems in the Northeast Asian RSC, in which at least three layers are intertwined concurrently and interactively: 1) a Sino-American regional layer, 2) interKorean layer, and 3) intra-South Korean layer. As the “Gordian knot” had been intricately woven, the Korean question has involved many complicated circumstances and has remained as a major sticking point in the Northeast Asian RSC.

1)Barry Buzan and Ole Wæver, Regions and Powers: The Structure of International Security (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), p. 43. 2)Ibid., p. 49. 3)Barry Buzan, Ole Wæver, and Jaap de Wilde, Security: A New Framework for Analysis (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1998), p. 201. 4)Barry Buzan and Ole Wæver, op. cit. p.144. 5)Ibid., p. 80. 6)Ibid., p. 46. 7)Hans J. Morgenthau, Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace, 4th ed. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1966), p. 406. 8)The so-called “Korean division system” has functioned as a kind of post-Korean War security regime through which particularly the United States and China could intervene as two main signatories of the Armistice in 1953. Moreover, the United States and China maintained their alliances with the two Koreas, respectively, and sponsored an inter-Korean military rivalry. Therefore, in the early Cold War era, the Korean division system was embedded in the context of the “Cold War in Asia,” symbolized by the Sino-American confrontation. Dong-jun Lee, Mikan no Heiwa: Beichu-wakai to Chosen-mondai no Henyo, 1969-1975 [Incomplete Peace: Sino-American Rapprochement and the Transformation of the Korean Question, 1969-1975] (Tokyo: Hosei University Press, 2010), pp. 4-11.

Ⅲ. Theoretical Matrix: From Conflict Formation to Security Regime or Security Community

As social structures, RSCs may be located along a spectrum depending on the degree of amity and enmity. That is, at the negative end lies conflict formation, where interaction arises from fear, rivalry, and mutual perceptions of threat. In the middle lies security regime, in which states still treat each other as potential threats, but have made reassurance arrangements to reduce the security dilemma among them. At the positive end of the spectrum lies a security community, in which states no longer expect or prepare to use force in their relations with each other.9) Under this categorization, Northeast Asia remains in the stage of

1. (De)Securitization Process and the Evolution of a RSC

As the CoS argued, the type of RSC could be transformed from one phase to another by internal and external transformations or by their intersubjective evolutionary process.12) One possible evolution of RSC could be expected by its internal dynamics, which is closely related to the presence of (de)securitization of “major” security issues because (de)securitization serves as an impetus for the RSC transformation.

The real essence of the (de)securitization theory, one of the three core concepts of the CoS,13) may well lie in its intersubjective understanding of security construction. According to this approach, security should be regarded as “a self-referential practice,” because it is through this practice that an issue becomes a security issue—not necessarily because a real threat exists, but because the issue is presented as such.14) Under this understanding, security is seen as the outcome of a specific social process rather than as an objective condition.15) Reasonably, it aims to analyze and critically question the processes through which threats and security are (de)constructed.

One theoretical paradigm dealing with securitization (the process of existential threat construction, articulation and persuasion) or desecuritization (the unmaking of securitization or the deconstruction of threat frames) conceives security as something stemming from a “speech act.”16) This approach contends that “the socially and politically successful ‘speech act’ of labeling an issue as a ‘security issue’ removes it from the realm of normal day-to-day politics, casting it as an ‘existential threat’ calling for and justifying extreme measures.”17) Accordingly, the CoS strongly focuses on elite and dominant actors, who articulate security issues in an institutional voice.18) Elite actors can be political leaders, bureaucrats, governments, lobbyists, and pressure groups.19)

Theoretical matrix provides a point of departure for an empirical analysis of security issues in RSC. However, it also raises some important theoretical shortcomings. First, the (de)securitization theory is profoundly linked to linguistics. Articulations are narrowly understood as pure speech acts. It follows an analytical narrowing that excludes all other kinds of (political and economic) practices and sources of meaning. Second, (de)securitization studies—while reminding the reader of the importance of discursive processes of (de)securitization—do not take into account the multilateral process of constructing meaning and the struggles within that process seriously. Specifically, whereas previous empirical studies of (de)securitization were trapped in state-centric descriptive methods that focused on describing which state is (de)securitizing what,20) the dynamic process of (de)securitization via increasingly pluralistic polities in RSC remains largely unexplored. In order to at least partly fill this gap, this article emphasizes the domestic political dynamics in the (de)securitization process, while shedding light on the interactions among the domestic and regional (or international) actors in RSC.

2. Domestic Political Factors in Desecuritization Process

The Northeast Asian RSC has many “traditional” security issues, such as the NLL, which defy desecuritization, while various identities and interests are intertwined with them. In the view of the “positive” evolution of the Northeast Asian RSC, the process of desecuritization far outweighs that of securitization, because despite the end of the Cold War, traditional threats remain strong and consistently hinder the transformation of it. The more the threats are desecuritized in the RSC, the more the RSC will evolve. The Northeast Asian RSC that remained in the stage of

One of the typical trends in Northeast Asia is the increasing number of actors attempting to maximize their own interests and values in domestic politics. On the other hand, globalization (or regionalization) poses new challenges to diverse domestic actors by threatening to deprive much of their vested interests and precious values. As a result, as more and more actors participate in the policymaking and priority-setting processes in their respective states, diverse domestic interests (groups) compete with one another in order to exert political pressures on the government in order to (de)securitize the threats of their concern.21)

In this context, we can hypothesize that if the actors pursuing desecuritization win domestic political competitions against the traditionally securitization-oriented actors, the possibility that particular old security threats can be desecuritized will be higher, and after, all the resources that have been monopolized by conventional threats will be reallocated to other issues. It could also eventually improve the security interaction driven by variations of amity/enmity in the RSC. Of course, in this process, international (or regional) actors tend to influence the process of desecuritization when they feel their values and interests are threatened.

In a figurative sense, this hypothesis may be compared to a method of untying “Gordian knots” as a metaphor for an intractable problem. Of course, we can cut the knots with a single stroke, as Alexander the Great did. However, the Alexandrian solution is fundamentally a method of “thinking outside the box.” Moreover, this drastic solution might be imprudent because it will require great sacrifices, and further, it will also be undesirable because it is not natural, but compulsory. One of the best choices for untying such knots is to make it loose, particularly using tweezers as such. Desecuritizing leadership by key decision makers in domestic politics can also work just like tweezers, which target to make room for loosening a knot. Once a critical knot (one of the most securitized issues, for example the NLL) is untied, it will be easier to untie another knot. Eventually, all of the Gordian knots will be untied, implying that the RSC is evolving to a more favorable place.

However, the desecuritization of conventional threats has faced many hurdles because the traditional security community, including the political and economic establishment, is prone to resist it. Furthermore, the Cold War structure still remains in Northeast Asia, where any efforts to desecuritize Cold War-type threats could engender conflicts of values and interests.

Against that backdrop, the Roh Moo-hyun government provoked farreaching competitions against securitization-oriented actors within South Korean society. The next sections analyze Roh’s desecuritizing endeavor regarding the NLL issue and discuss its implications from the perspective of an evolving Northeast Asian RSC.

9)Barry Buzan and Ole Wæver, op. cit., pp. 53-54; Barry Buzan, People, State and Fear: An Agenda for International Security Studies in the Post-Cold War Era, 2nd ed. (Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Weatsheaf, 1991), p. 218. 10)Barry Buzan and Ole Wæver, op. cit., p. 173. 11)Said Haddadi, “The Western Mediterranean as a Security Complex: A Liaison between the European Union and the Middle East?” Jean Monnet Working Papers in Comparative and International Politics 24 (November 1999), available at

Ⅳ. NLL Trouble in the Northeast Asian RSC

No better proof than the NLL exists to show that the Korean Peninsula is still in a state of war. Even though the two Koreas are both independent states as members of the United Nations, no territorial border exists between them because a peace regime has yet to be established. A cease-fire line exists on land, referred to as the Military Demarcation Line (MDL), and a jurisdiction line at sea, dubbed the NLL, which is not mutually agreed upon. Therefore, the NLL has been regarded as the cause of its evolution into a “sea of dispute,” and as one of the most securitized powder kegs in Northeast Asia. Who would want to securitize or desecuritize the NLL? Here I explore key actors’ political attitude against the NLL issue, after looking through its historical and legal background.

The NLL is a derivative of the Korean War. During the cease-fire negotiations spanning two years from 10 July 1951, the two sides could not come to an agreement on a maritime demarcation line. Thus, though the Korean Armistice Agreement was signed on 27 July 1953, the maritime demarcation issue remained unresolved. James Lee, who had been posted as the chief delegate at the Military Armistice Commission (MAC) of the United Nations Command (UNC) from 1982 to 1994, testified on the NLL issue as follows: “There is no indication of a consented MDL on the West Sea nor extension of the NLL in any proposition of the treaty, not to mention any agreement following the treaty in any of the Armistice map no. 1, 2, 3 and any assembly records at MAC.”22)

After the armistice went into effect in 1953, the NLL was reportedly promulgated on August 30th of that year based on a line drawn unilaterally by US Army General Mark W. Clark,23) then Commander of the US-led UNC, chiefly out of concern over the possible violations of South Korean vessels, not North Korean ones. In those days, the United States thought that the NLL was more necessary to prevent South Korean president Rhee Syng-man from violating the armistice by launching an attack on North Korea.24) the UNC did not bother to give notice to North Korea. In short, its main objective for drawing the NLL was to limit patrol activities of the South Korean navy and to prevent any accidental armed clashes between the two Koreas.25) Accordingly,

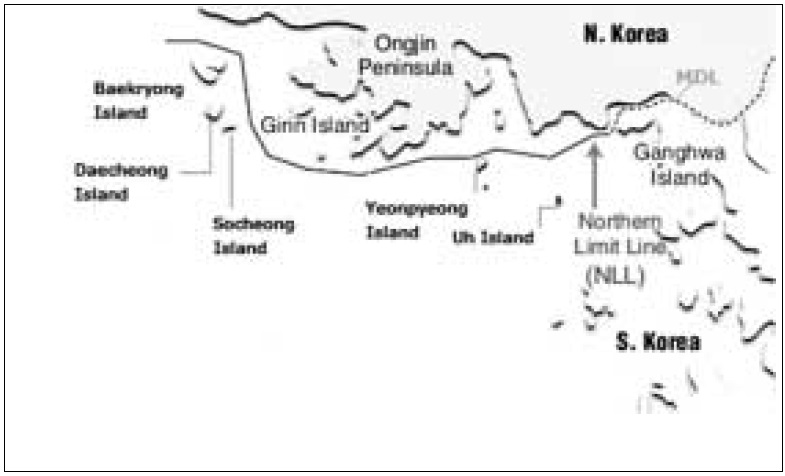

The NLL was set at a distance of at least three nautical miles from the North Korean coast, which at the time represented the international standard for territorial waters. Below the NLL, there are several small islands (Baekryeong, Daecheong, Socheong, Yeonpyeong, and Uh) which, despite geographical proximity to North Korea, fell under the South’s jurisdiction.

The North Korean cabinet had issued a decree in March 1953 to announce the extension of their territorial waters up to twelve nautical miles.26) However, in the following decades, the North did not challenge the NLL until the early 1970s after it had built up its naval forces. As North Korea’s maritime traffic expanded, the NLL also limited its access to international shipping routes, forcing its merchant ships to take a lengthy detour, adding to fuel costs and transit times. By 1973, an increasing number of coastal nations used the twelve-nautical-mile limit for territorial waters, which today remains the international standard, as codified in the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).27)

During the 346th MAC in December 1973, North Korea raised the stakes in an attempt to assert further control over the contested waters, by pronouncing that the waters on the northern side of the extension line of the provincial boundary between Hwanghae and Kyeonggi provinces were North Korean territorial waters, and also by demanding that South Korean and UNC ships require North Korean permission in order to travel to or from the West Sea islands.28) However, North Korean vessels had crossed the NLL a total of 219 times from October 1973 to February 1974.29)

While North Korea contested the NLL, a difference in position emerged between South Korea, which regarded the North’s crossings as violations of the armistice agreement, and the United States, which did not. In a recent analysis of the NLL history in the 1970s, Michishita Narushige quotes from a private US State Department memo as below.30)

South Korea soon sought to shift attention away from the question over the line’s legality by adopting in 1974 its “

In response to South Korean sasu policy, North Korea countered by reasserting the standard of the twelve-nautical-miles territorial waters33); however, it was not until July 1999 that North Korea formally proposed its maritime line as a military demarcation during UNC-KPA (Korean People’s Army) General Officer Talks. In a special communique issued on 2 September 1999, the KPA General Staff reiterated the July proposal by denouncing the NLL, and proposing to provide for all commercial transit two corridors, two nautical miles wide each, from South Korea’s five islands.34) Despite the proclamation, South Korea conducted its business as before, and the North could not enforce its proposed line. However, these fundamental disagreements were what triggered continual armed conflicts.

Actually, North Korea’s 1999 pronouncements came in the months following a nine-day naval battle south of the NLL on June of that year, which resulted in the sinking of several North Korean torpedo boats and estimated deaths of thirty North Korean sailors. A second West Sea skirmish occurred on 29 June 2002, when, according to South Korea, North Korean crafts opened fire after two South Korean navy vessels attempted to enforce the NLL. The naval clash, which lasted only twenty minutes, sank a South Korean patrol ship and damaged a North Korean vessel, killing six South Korean crewmembers and an estimate of thirty North Koreans.

In light of more recent hostilities in the West Sea during President Lee Myung-bak’s tenure (February 2008-February 2013), the 1999 and 2002 naval battles occurred during the administration of Kim Dae-jung (February 1998-February 2003), whose “Sunshine Policy” pursued engagement rather than confrontation with the North.35) The continuous naval clashes complicated South Korean efforts toward detente by stirring criticism among skeptics who questioned the effectiveness of the Sunshine Policy.

1) North Korea: Securitizing or Desecuritizing Actor

North Korea’s position on the NLL is clear. Following the 2002 clash, North Korea’s state-owned media asserted that “The ‘northern boundary line’ ⋯ is a bogus line unilaterally and illegally drawn by the UNC in the 1950s and our side, therefore, has never recognized it.”36) Pyongyang has not challenged Seoul’s sovereignty over the five islands designated in the armistice, but has made it clear that these lie within the North Korean territorial waters. Actually, as aforementioned, since 1973, North Korea has made extensive efforts, international or otherwise, such as statements, NLL crossings, and armed clashes, in order to revise the status quo.37)

A variety of reasons may explain why North Korea has tried to securitize the NLL issue. For example, Victor Cha argues that the North Koreans initiated the 1999 naval altercation, despite the risk of military losses, in order to create a crisis that would later establish the NLL as an issue of negotiation, particularly with the United States.38)

However, it is worthy to note that the North’s challenge to the NLL derives principally from economic reasons. Both the 1999 and 2002 skirmishes began as confrontations involving patrol boats guarding fishing vessels in areas where highly valued blue crabs (or

2) The US and China: “Passive” Support for Desecuritization

Although it is actually the author of the NLL, the United States has maintained a low profile on the NLL issue, believing it as a problem to be resolved between the two Koreas. Technically, the United States lacks the authority to negotiate a final maritime boundary with the North, because the UNC has the ultimate responsibility of maintaining security along the NLL until the conclusion of a permanent peace treaty.39) In addition, Washington does not want to undercut South Korea’s position on the NLL or be pulled into a bilateral negotiation about territory with the North that could hurt its relationship with the South. In the end, US officials have not taken a clear position on the issue, but are concerned that clashes along the NLL could escalate into a broader Korean conflict and endanger Sino-American strategic relations.

Despite its involvement with other Korean issues, particularly as a sponsor of the Six-Party Talks (6PT), China also has had relatively little to say about the NLL issue. Most likely, China has sympathy for its ally’s position, and Beijing’s chief goal is to resolve the dispute peacefully without disrupting regional stability. Chinese leaders are more concerned with resolving China’s own disputes with the two Koreas regarding the overlapping maritime claims in the West Sea, where important oil drilling issues are at stake. In short, China sees this largely as a dilemma to be resolved between the two Koreas, while weighing both its strategic relations with the United States and alliance relations with North Korea.

3) South Korea: Securitization vs. Desecuritization

If there were some questions about South Korea’s willingness to desecuritize the NLL issue during the Roh Moo-hyun administration, during Lee Myung-bak’s tenure, Seoul’s policy was clear: “The NLL is nonnegotiable.” In March 2008, General Kim Tae-young, in a testimony to the National Assembly for his confirmation as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS), declared that “It is a quasi-border, part of the nation’s territorial sovereignty.”40) Following the conventional “

On the other hand, many South Koreans are well aware of the fact that the NLL is not a territorial borderline, but just a ceasefire line. They also agree on the need for making some form of an agreement with the North, in hopes of preventing further clashes. Furthermore, some progressive coalitions support renegotiations of the NLL issue with the North for a new era of reconciliation, cooperation and peaceful coexistence on the Korean Peninsula.

The idea of progressive coalitions in South Korea shows a very close analogy of a typical neoliberal institutionalist approach to the issue of security in international relations. It posits that states seek to maximize absolute gains through cooperation. Cooperation is never without problems; yet, states will shift loyalty and resources to institutions if these are seen as mutually beneficial and if they provide states with increasing opportunities to secure interest.42) However, in South Korean society, the idea of desecuritizing the NLL issue is not a predominant view. The country is still struggling against the traditional realism-based notion.

22)Mun-hang (James) Lee, JSA-Panmunjeom (1953-1994) (Seoul: Sohwa, 2001), p. 87. 23)James Lee made reference to an “Operational Control Line” drawn by the US navy in 1958, and Kotch and Abbey mentioned a “UNC statement” dated 30 August 1953; however, they do not include a full citation. See, Ibid., p. 92; John Barry Kotch and Michael Abbey, “Ending Naval Clashes on the Northern Limit Line and the Quest for a West Sea Peace Regime,” Asian Perspective 27-2 (2003), p. 176. 24)As is well known, in the months leading up to the signing of the armistice, Rhee had repeatedly attempted to sabotage truce negotiations. The United States eventually secured Rhee’s cooperation, though only after making several commitments to South Korea in the form of a mutual security treaty as well as military and economic assistance. Wan-bom Lee, “1950 Nyeondai Isungman Daetongryeong gwa Miguk ui Kwankye e kwanhan Yeongu” [President Rhee’s Autonomy toward the US in the 1950s], Jeonshinmunhwa Yeongu 30-2 (June 2007). 25)Ministry of National Defense (MND), The Republic of Korea Position Regarding the Northern Limit Line (Seoul: MND, 2002), p. 5. 26)Dong-uk Kim, Hanbando Anbo wa Gukjebeop [The Korean Peninsula: Security and International Law] (Paju, ROK: Hanguk Haksul Jeongbo, 2010), pp. 81-82. 27)The 1982 UNCLOS, to which both Koreas are also signatories, generally adheres to an “equity principle” for territorial claims, but does not adhere to what is “equitable.” See, International Crisis Group (ICG), “North Korea: The Risks of War in the Yellow Sea,” Asia Report 198 (December 2010), p. 3. 28)Jon M. Van Dyke, Mark J. Valencia, and Jenny Miller Garmendia, “The North/South Korea Boundary Dispute in the Yellow (West) Sea,” Marine Policy 27-2 (March 2003), p. 64. 29)Michishita Narushige, North Korea’s Military-diplomatic Campaigns, 1966-2008 (London: Routledge, 2009), p. 64. 30)Ibid. 31)For an argument that the NLL is integral to the armistice, see Charn-kiu Kim, “Northern Limit Line Is Part of the Armistice System,” Korea Focus on Current Topics 7-4 (JulyAugust 1999), pp. 103-104. 32)Dong-jun Lee, op. cit., p. 284. 33)Furthermore, on 1 July 1977, North Korea declared a 200 nautical-mile economic zone and on 1 August 1977, North Korea unilaterally declared a “Sea Demarcation Line.” 34)MND, op. cit., p. 17. 35)The Sunshine Policy is most commonly identified with two of its defining principles: (1) cooperation and reconciliation with North Korea; and (2) no intention of absorbing the North. After the 1999 firefight, analysts speculated that the North was using the NLL to test the US resolve; however, for the South Korean government, its response served to demonstrate the Kim administration’s commitment to a third principle of the Sunshine Policy: (3) no tolerance of armed provocation by the North. Key-young Son, South Korean Engagement Policies and North Korea: Identities, Norms and the Sunshine Policy (London and New York: Routledge, 2006), pp. 97-100. 36)“Statement by Spokesperson of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs,” Korean Central News Agency (30 June 2002). 37)Young-koo Kim, “A Maritime Demarcation Dispute on the Yellow Sea, Republic of Korea,” Journal of East Asia and International Law 2-2 (October 2009), pp. 491-496. 38)Victor D. Cha and David C. Kang, Nuclear North Korea: A Debate on Engagement Strategies (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), p. 73. 39)John Barry Kotch and Michael Abbey, op. cit., p. 183. 40)“General Kim Tae-young Says, NLL a Quasi-border,” Yonhap News (26 March 2008). In particular, some NLL defenders maintain that North Korea has in fact accepted the NLL as the border through the “1992 Inter-Korean Basic Agreement,” which was the only agreement made pertaining to the NLL, and further stipulates that “Until a new sea nonaggression demarcation line is established, the area of non-aggression will be maintained on the lines that both sides have controlled up until this point” (Article 10). However, the former of this clause strongly suggests the possibility of renegotiation on the maritime border between the two Koreas. 41)“Lee Calls for Life-risking Defense of Western Sea Border,” Korea Times (19 October 2012). 42)Steven L. Lamy, “Contemporary Mainstream Approaches: Neo-Realism and NeoLiberalism,” in John Baylis and Steve Smith (eds.), The Globalization of World Politics, 3rd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), pp. 205-224.

Ⅴ. Struggles on Desecuritization of the NLL Issue

In his inaugural address in February 2003, President Roh Moo-hyun declared his intention not only to retain the “Sunshine Policy” but to also expand its scope and content in order to build a “structure of peace” on the Korean Peninsula. Dubbed as the “Policy for Peace and Prosperity,” it aimed “to reinforce peace on the Peninsula and promote co-prosperity of the two Koreas” so as to build a foundation for peaceful unification.43) Furthermore, through the successful implementation of the policy, the Roh government hoped to transform South Korea into the economic hub of Northeast Asia.

For realizing co-prosperity, what is needed first is to recognize the North as a counterpart, not as an enemy. According to Alexander Wendt, this is because states will behave in ways that make them existential threats once the logic of enmity is initiated; and thus, the behavior itself becomes part of the problem.44) Actually, unlike its predecessors, the Roh government did not define North Korea as the “

1. Roh Moo-hyun’s Attempt at Desecuritization of the NLL Issue

Under the Roh government, the goal of co-prosperity through economic cooperation with Pyongyang clearly had become its top priority. In spite of the rising tensions triggered by the North Korean nuclear crisis, the Roh government made all endeavors to promote major inter-Korean projects: (1) the construction of the Kaesong Industrial Complex (KIC); (2) the linking of two key railways and roads between the two Koreas; and (3) the continued development of the Mount Kumgang Tourism Zone. Apparently, the Roh administration assumed that the promotion of inter-Korean reconciliation through economic cooperation would help reduce tensions and secure peace and security on the peninsula. Its policy on the NLL was also based on an assumption that the only possible way for peace in the West Sea is through both confidence building measures (CBM) and economic cooperation based on “reciprocal benefit.” However, Roh’s NLL approach could not produce satisfactory results for a fairly long time, because military talks, which aimed to establish CBM, dragged down the talks on economic cooperation.

Since May 2004, the Roh government had actively offered the North various CBM proposals, such as communication link between the two naval commands in the West Sea, through the inter-Korean general officers’ talks. However, the North Korean delegation instead emphasized that the key to resolving all military problems was abolishing the “illegitimate NLL” and drawing a new maritime boundary NLL. In the end, since 2006, the South proposed the establishment of a “West Sea Peace Zone” that would include a joint fishing area, stressing that a process of CBM and the establishment of a peace zone would no longer require a military demarcation line, such as the NLL. However, the talks also reached deadlock as the North did not change its stance on the NLL.46)

Roh’s security blueprint for the NLL more clearly showed its silhouette as the second inter-Korean summit was due to be held in early October 2007, which took place seven years after the first such summit in 2000. His plan was to find a solution for the NLL issue more comprehensively while constructing a special economic zone in the North Korean city of Haeju, Hwanghae province, an outpost for North Korean navy, and the peace zone near the NLL.47) He believed that it was necessary to approach the NLL issue within the context of the bigger picture, i.e., constructing a peace area on land and sea altogether, which could transcend the boundary concept, such as the NLL. Apparently, the plan had constructivist traits.

For Roh, the NLL itself is an ideational structure, rather than a neorealist material structure. The “NLL as territorial border” was a social fact, discursively and intersubjectively produced and reproduced, and eventually reinforced as “territorial border” in the process of deadly confrontations. In that process, the origin of the NLL, i.e., how it came to existence, is not important any more. NLL would exist only as a territorial “border line.” However, Roh set forth a counterargument to this conventional concept, which was reproduced as a solid social construct. Over the NLL controversy, Roh expressed his thoughts as follows: “The NLL was unilaterally drawn (by the United Nations), and we must remember this. We would be misleading the public if we say the NLL is a territorial borderline. North Korea is also a part of our territory, according to the Constitution. ⋯ In the case of North Korea, we need reverse psychology.”48)

Roh’s speech act was the language of desecuritization, intended to deter the securitization of the NLL issue. If the NLL was not a borderline, then there would be no reason for the NLL to be the security referent. In the extended vein, Roh’s initiative encompassed the West Sea itself. The security dilemma in the West Sea as a whole is also a social structure in which the two Koreas distrust each other and imagine worst-case assumptions about the other’s intentions. As the structure was constituted historically and intersubjectively, it could be reconstituted through the change of agents’ ideas. The theory of structuration, advocated by Anthony Giddens, implies that actors can recreate structure through their practices and interactions.49) Roh, as a human agency, imagined change in security structures, with the idea for mitigating and eventually putting an end to the endless spiral of enmity between the two Koreas. South Korea’s national interest was also subject to change as the referent object of security can be broadened.

In the end, during the second inter-Korean summit held on 2-4 October 2007 in Pyongyang, Roh proposed his idea to the North Korean leader Kim Jong-il, then chairman of the National Defense Commission (NDC). The mutual agreement to set up a “Special Peace and Cooperation Zone (SPCZ)” in the West Sea, which was aimed at transforming the heavily militarized waters into a maritime region for economic cooperation, was documented in the “Declaration on the Advancement of South-North Korean Relation, Peace and Prosperity (October 4th Declaration).” Both also pledged to negotiate a joint fishing area and to discuss “measures to build military confidence” in order to prevent further naval clashes (Article 3). The tangible result of the co-desecuritizing attempt by the two Koreas emerged for the first time since the Korean War.

Achieving this kind of arrangement would offer significant economic gains for both Koreas. Improved communication and commercial links across the two Koreas along the western coast would open up important routes for interKorean transactions, which could also benefit from tapping the potential of the maritime region as a logistical hub adjacent to China’s northeastern seaboard. More directly, South and North Korean fisherman could catch more blue crabs in the joint fishing areas. Cooperation on utilizing the Han River estuary would allow other economic benefits. Thus, military tension in the turbulent West Sea would be mitigated accordingly. A “lose-lose” game could now turn out to be a “win-win” game. Roh apparently seemed to gain an important foothold for coexistence and co-prosperity between the two Koreas, by co-desecuritizing one of the hottest “powder kegs” in the Northeast Asian RSC. However, Roh was not successful in establishing a shared idea on the NLL issue domestically.

2. Domestic Split and the Frustration of Roh’s Idea

While the 2007 summit may have committed both Koreas to a vision for addressing the recurring sources of conflict and creating incentives for cooperation in the West Sea, the responsibility for hammering out the essentials of implementation fell initially to delegates at the subsequent ministerial and general-level military talks. However, several rounds of talks failed to agree on realizing the October 4th Declaration. Negotiators differed on key issues, such as the size and location of the joint fishing zone along the NLL,50) while the North insisted its territorial waters extend twelve nautical miles from the coast line, south of the NLL in some areas.51) In the end, follow-up meetings were suspended since December 2007 because the two Koreas could not narrow the discrepancies on concrete details; the turnover of power in the South took place in February 2008.

Yet, the debate over the NLL was not limited to the inter-Korean level. The real and direct cause of Roh’s failure in desecuritizing the NLL issue was that he was not successful in producing a consensus domestically. As soon as Roh returned from Pyongyang, a political firestorm erupted over the declaration. The idea of a “peace zone” or “economic cooperation zone” in the West Sea unnerved most conservatives, including the main opposition party (Grand National Party), because they had long held the image of the NLL as “territorial border” in the process of dire confrontations.

When recalling the historical background of the NLL mentioned above, Roh’s approach was not a misleading one. Moreover, Roh’s idea was based on state interests, and aimed for structuring sustainable peace. However, the chief concern of conservative camps over territorial claims was more realistic. Many security-wise conservatives envisioned that the peace zone would undermine the effect of the NLL as a sea border due to the North’s free passage close to the Han River estuary, which leads to the capital city Seoul and also Incheon, Seoul’s main shipping port, as well as a major international airport. Conservative opposition to repositioning the NLL southward is based on fears that the South would be more vulnerable to infiltration and that the West Sea Islands would be left isolated and indefensible.52) South Korea’s veterans associations and organizations of military reservists maintained that the weakening of the NLL by the idea such as “joint fishing area” could lead South Korea to self-disarmament. They still considered North Korea as an enemy rather than a partner for co-prosperity.

Furthermore, despite Roh’s desires and instructions for desecuritizing the NLL issue, a deep inter-agency divide also existed within his government. In particular, the feud between the Defense and Unification ministries regarding the NLL deepened after the summit. While Unification Minister Lee JaeJoung, an ardent advocate of engagement policy toward the North, reiterated his view that the NLL could be discussed and negotiated, Defense Minister Kim Jang-Su, who accompanied Roh to Pyongyang for the summit, said upon his return to Seoul that “the NLL will not be affected by the agreement to create a maritime peace zone” and that “it is a main achievement of the summit that we have successfully defended the NLL.” Kim even broke with President Roh and pledged to “defend the NLL” in talks with his counterpart in Pyongyang in late November 2007.53) Although Roh wished to establish his legacy by locking in the agreements reached at the summit, his political influence vanished as his term as president was soon to end.

While domestic controversies over the NLL were heating up, Seoul’s bargaining power was also decreasing in the talks with Pyongyang. Moreover, Roh’s NLL approach garnered timid support from the United States and China. While the United States emphasized North Korea’s denuclearization, which had not been agreed in the inter-Korean summit, China welcomed it outwardly but assumed a wait-and-see attitude.54) The UNC, the originator of the NLL, also took a cautious position that the sea border could be negotiated by the two Koreas, but any changes to the NLL should be approved by the UNC.55)

As Roh’s presidency term was coming to the end, his successor Lee Myungbak disagreed with Roh. Many critics argued that it was irresponsible for Roh to implement the agreement with the North before his successor would be sworn into office. With the transfer of power, Roh missed the timing and momentum to realize matters already agreed upon between the two Koreas. As is well known, Lee, who came to power on a platform calling for a harder line against the North, first annulled the October 4th Declaration, reversing the policy of engagement. Furthermore, in the aftermath of North Korea’s shelling of Yeonpyeong Island in November 2010, most South Koreans were outraged and appalled by the attack. In a South Korean poll taken at the time, over 80% said that the South Korean army should have undertaken a stronger military response to the shelling, and nearly 65% favored the government maintaining a hardline policy against the North.56) As an outcome, Pyongyang responded to Seoul’s new policy of disengagement by making plain the volatility of confrontation and turning up the pressure in the West Sea’s contested waters.57)

Given the current state of inter-Korean relations, Roh’s desecuritizing endeavor seemed to be a total failure. However, on the contrary, as tensions in the West Sea became higher after Roh failed to desecuritize the NLL issue, the South Korean society began to reevaluate Roh’s idea and recognize its value. Actually, incumbent President Park Geun-hye (February 2012-present), leader of South Korea’s moderate right, promised in the 2012 presidential race that she would respect the October 4th Declaration. Park also said that she hoped to build trust with the North, though in far more transparent ways, and work for genuine, long-term peace and prosperity.58) Arguably, Roh’s struggle for desecuritization of the NLL is now continuing even after his death in 2009.

43)Se-hyun Jeong, “First Year of the Roh Moo-hyun Administration: Evaluation and Prospects of North Korea Policy,” Korea and World Affairs 28-1 (2004), p. 7. 44)Alexander Wendt, Social Theory of International Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), p. 263. 45)National Security Council (NSC) of ROK, Peace, Prosperity and National Security: National Security Strategy of the Republic of Korea (Seoul: NSC, 2004), p. 15. 46)Ministry of Unification (MOU), Unification White Paper (Seoul: MOU, 2007), pp. 217-218. 47)“Roh Aims to Create Unified Economy Zone,” Hankyoreh (14 August 2007). 48)“Roh Says NLL Is Not Official Territorial Line,” Korea Herald (12 October 2007). 49)Anthony Giddens, Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1991), pp. 187-201. 50)The South proposed two zones—one on each side of the NLL; however, the North insisted that both be established south of the NLL, implying a redrawing of the border. 51)“N. Korea Claimed 12-mile Territorial Waters at Last Week’s Talks,” Korea Herald (2 December 2007). 52)Terence Roehrig, “Korean Dispute over the Northern Limit Line: Security, Economics, or International Law?” Maryland Series in Contemporary Asian Studies 3 (2008), p. 26. 53)“Defense Chief Vows to Defend NLL,” Korea Herald (18 October 2007). 54)“The Reactions and Assessments of the October 4th Declaration in the US, China, and Japan,” Seoulshinmun (6 October 2007). 55)“Why the Haste?” Korea Herald (16 August 2007). 56)“More S. Koreans Harden against N.K. after Island Attack: Survey,” Korea Herald (29 November 2010). 57)Leon Sigal, “Can Washington and Seoul Try Dealing with Pyongyang for a Change?” Arms Control Today (November 2010), available at

This study empirically analyzed the attempted desecuritization of the NLL under the Roh government. It emphasizes how important domestic factors are in desecuritizing threats in a RSC. This was the process of competition among different political identities and the process of transformation from issues of high politics into issues of low politics. The case of desecuritization, not securitization, was selected because desecuritization of “traditional” threats is important for the evolution of the Northeast Asian RSC, which still remains in the stage of

Despite many limits, the RSC theory approach to the security of Northeast Asia is highly effective as it fills the vacuum of rationalist accounts. It opens ways by which to understand the “deep” politics of international relations, and to imagine changes of the security structure that otherwise would seem to be staunchly fixated and unchangeable. Those who believe identities and interests are exogenous and fixed; hence, they could not understand and imagine such changes.

The Northeast Asian RSC has many securitized issues, such as the NLL, which are all intertwined like Gordian knots and cannot be desecuritized with ease. One way to convincingly desecuritize a traditionally securitized issue is to have the actors pursuing desecuritization win domestic political competitions against the securitization-oriented actors. In desecuritizing a securitized issue domestically, which, in the end, can contribute to the evolution of a RSC, the socially and politically successful role articulated by political leaders is very important. President Roh’s NLL approach was, albeit unsuccessful, also aiming for reducing the security dilemma by desecuritizing Cold War-type conventional threats.

On the other hand, Roh also more fundamentally questioned how we are to understand the world. What the self thinks makes the world, but together with what others think. The present security structure of the Korean Peninsula is what the two Koreas and the surrounding four powers constructed. For selfconscious agents, anarchy of the Korean Peninsula and Northeast Asia is what states make of it. If the thought and ideas that constitute the existence of international relations change, the Northeast Asian RSC in the stage of

![[Planned] Special Peace and Cooperation Zone in the West Sea](http://oak.go.kr/repository/journal/17750/NRF010_2013_v11n1_83_f002.jpg)