>

DOMINANT PRIORITIES ON NORTH KOREA’S FOREIGN POLICY

This focus on domestic politics implies that Pyongyang’s foreign policy may appear to be a response to changes in other powerful states’ foreign policy but they really reflect the domestic environment in a number of areas. If one fails to consider how a state’s leader and its prevailing ideas or ideologies shape its foreign relations, one may create an analysis that is inadequate and thus perpetuates misunderstandings and misperceptions (Kim 2011). In the case of foreign policy analysis, it is imperative to identify the point of theoretical intersection between the most important determinants of state behavior including material and ideational factors (Hudson 2006). This research focuses primarily on how decision makers’ domestic policy priorities impact North Korea’s foreign policy behaviors.

North Korea’s foreign policy analysis tends to rely on domestic policy determinants. Herbert Simon argues that one needs to know where preferences originate (Simon 1985). In this research, domestic priorities of foreign policies are based on three basic human motives: power, achievement, and social affiliation organize what individuals know about foreign policy, and should also shape how they make their decision. In foreign policy, these three motivations are reflected as security, identity, and prosperity (Chittick 2006).1

Therefore, this article shows that North Korean foreign policy goals are motivated by three domestic priorities or preferences: security, identity, and prosperity. By focusing on these preferences (or motivations) one can understand the logic of DPRK’s foreign policy decision making strategy:

1)

2)

3)

Based on the theoretical reasoning above, a testable hypothesis can be derived:

Both North Korea and China are communist nations that share cultural characteristics. At this time, the Sino-DPRK alliance is still effective and valid. Moreover, North Korean leaders consider that “China does not pose any security or ideological threat” (Park 2002). Given its military tensions with South Korea and the United States, and its general diplomatic isolation, North Korea needs China’s support (Lee 2010).

Historically, China has used North Korea as a buffer zone between China and U.S. forces stationed on the Korean peninsula. This is not the only role North Korea serves for China, however, as each side considers the relationship a “friendship cemented in blood.” The Korean War served as a reminder to the Beijing leadership that Korea is important to China’s own national security. In 1961 China and North Korea signed the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance. This treaty committed either party to come to the aid of the other if attacked. North Korea and China relations since developed within the context of the treaty. Both nations saw their mutual defense alliance in terms of protecting their shared communist ideology, and China became a huge economic supporter of North Korea.

Also, China had a great influence on the political and social structures of North Korea. After the Cold War, the importance of ideology faded and economic interest began to shape the relationship between these two countries. Since then subtle changes have occurred in China-North Korea relations. Starting in the early 1980s, China has implemented a pragmatic national developmental strategy of reform and openness. In doing so, China has moved to adjust its relationship with North Korea to one that is similar to its relationships with other countries.

In this context, North Korea does not perceive any struggle for security or regime legitimacy with China. Given that North Korea has no other substantial trade partners, it is reasonable to assume that Pyongyang’s policy toward China would be geared toward developing its economic relations with Beijing.

>

HISTORICAL EXPLANATION AND CONTENT ANALYSIS

In order to analyze the policy behavior of North Korea toward China, this study uses the “process-tracing” method (George and Bennett 2005).2 In this way, it may complement the historical method such as genetic or sequential explanation that show in detail how one event leads to another (George and Bennett 2005). Therefore, the purpose of applying the process-tracing method to this study is to discover how the variations of North Korea’s domestic policy preferences, colored as they are by North Korea’s perceptions of the outside world, have influenced its policy toward China.

In order to clarify the DPRK’s foreign policy behavior, this study also employs empirical methods such as content analysis and event data analysis.3 This method provides a systematic and rigorous use of verbal symbols in mass or official communications (or even in interviews), employing an explicit conceptual scheme for assembling, typologizing, and measuring the content of communication. There is no other effective way but to use Kremlinological method—a classical way of analyzing communist countries’ foreign policy through tracing symbolic interactions reported by media. Symbolic interactions include attendances, addresses, and speeches at celebratory occasions, newspaper editorials, and official comments or memoranda.

This article features a content analysis of

This study counts the frequency of key words as denoting security, identity, and prosperity aimed toward China. Changes in frequency are a useful indicator for understanding Pyongyang’s need for perception and preference of foreign policy. The regime in Pyongyang presents its needs through the frequency of specific words in

>

SAMPLING, CODING RULES, AND PROCEDURES

At first, editorials (

1In this sense, I would adopt that a combination of realism and liberalism as well as constructivism is regarded as a major theoretical frame to explain and analyze the inter-state affairs and foreign policy behavior of countries. In sum, realists seeking to increase security are “satisfiers.” They emphasize the logic of effectiveness because they want their minimum needs met. The logic of effectiveness places an emphasis on relative differences between the outcomes achieved by actors. Realists emphasize the logic of effectiveness because they are preoccupied with security. Liberals prefer the logic of “efficiency” because they are most interested in prosperity or economic values. And “idealists” use the logic of acceptability because they are most concerned with the values of community (Chittick 2006, 14). 2According to George and Bennett (2005), process-tracing is a special type of historical explanation that enables the analyst to identify causal links within a single case. 3According to Krippendorff, content analysis is “a research technique for making replicable and valid inferences from texts (or other meaningful matter) to the contexts of their use” (Krippendorff 2004, 8).

SALIENT MANIFEST GOALS AND STRATEGIES IN THE DPRK’S FOREIGN POLICY

>

THE DPRK’S DECISION-MAKING PROCESS

To understand the DPRK’s foreign policy, one must understand domestic politics in North Korea under the one-party communist system, as well as the North Korean mechanism for foreign policy decision-making. In North Korea, the pivot of the system is that “all major issues of international affairs were deliberated and decides upon at the level of the top leadership: at the Korean Workers’ Party (KWP) congresses, at plenary meetings of the KWP Central Committee, and the meeting of the KWP Central Committee Politburo and Secretariat” (Zhebin 2012, 184). In the DPRK, the conditions for objective policy analysis are very limited because the major and crucial issues of foreign policy have been monopolized by a very narrow inner-circle of people at the top of the KWP. Therefore, the Politburo gets deeply involved in only the most important foreign policy issues (Zhebin 2012). The regime in Pyongyang has developed formidable tools to influence society, ranging from security organizations to ideological control. The two principal domestic security organizations are the Ministry of People’s Security (MPS) and the State Security Department (SSD). Permission from the MPS is required to change one’s residence, job, or even to travel within the country. Furthermore, the MPS controls the distribution system, which was the primary source of food for the population until the famine years of the mid-1990s.

>

SALIENT MANIFEST GOALS AND STRATEGIES IN THE DPRK’S FOREIGN POLICY

Regime survival has remained paramount for North Korea even during its continued periods of isolation following the end of the Cold War. In 1992 the regime’s New Year’s address warned against “imperialists and enemies ... concentrated on attacking our country” and proclaimed North Korea as “the last fortress of socialism” (

In 2012 North Korea’s New Year’s Joint Editorial focused on strengthening internal solidarity around Kim Jong Un. It did so by emphasizing the legacy of Kim Jung-Il and concentrating on building a “strong and prosperous nation” (

North Koreans believe that system change signifies system collapse. In this sense, North Korea’s primarily foreign policy goal is “national security or regime survival’ against the traditionally adversarial systems of the United States, South Korea and Japan. All political systems also try to legitimize their power from a single source: the support or consent of the people. Even in very authoritarian countries like North Korea, the regime tries to support itself by getting consent from the people. Regime legitimacy is formed from an ideology.

In order to figure out North Korea’s foreign policy orientation, one must understand its unique political culture steeped in

In addition,

North Korea has responded with policy objective strategies and tactics that are consistent with its political system. North Korea requires specific set conditions such as a strong military for defense, the preservation of legitimacy over that of South Korea’s government, and the protection of its ideologies from the capitalist culture. Economically, Pyongyang maintains a “closed door” policy which includes protecting against outside mass-media and interaction with the outside world as an extension of its “information control” policy. North Korea borrows various policies from the Chinese economic development model designed to alleviate its devastating economic reality.

NORTH KOREAN POLICY TOWARD CHINA

>

HISTORICAL AND CULTURAL CONTEXTS OF SINO-DPRK RELATIONS

Initially, it is useful to succinctly understand the historical and cultural legacy that supports discernments in how the North Korean leaders have perceived the Chinese government’s identity, and formed its policy objectives toward China. The PRC-DPRK relations began unofficially when U.S. forces came to South Korea’s defense at the outset of the Korean War and was formalized in July 1961, under the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance (Nanto and Manyin 2010).

North Korea and China were bonded by their shared communist ideologies, by blood-ties through fighting together during the Korean War, and by China’s reconstruction efforts in Pyongyang after the Korean War. In this regard, China and North Korea have long been considered as special allies, with the relationship characterized “as close as lips and teeth.” The share interests and identities between the two governments were enough to assure cordial relations for decades. But these mutual affinities began to diverge in the early 1980s when the PRC initiated economic reforms and open marketing systems under Deng Xiaoping’s leadership, and when Beijing normalized diplomatic relations with South Korea in 1992 (Nanto and Manyin 2010). While the relationship has fluctuated over the years, official ties (measured in terms of bilateral meetings) have grown stronger along with the economic ties between the two countries (Snyder 2009). While the basic Cold War relationship remains intact, China’s views on the DPRK have undergone some changes since Hu Jintao took power in China in 2002.

Historically, the Korean War served as a reminder to the Beijing leadership that Korea is important to its own national security. As a result, in October 1950, China reentered the Korean peninsula via the Yalu River and directly confronted the United States militarily. This conflict ended in a military stalemate three years later. The casualties on both sides, however, were tremendous. According to Chinese statistics, the U.S. casualties reached 390,000 and Chinese casualties reached 115,000 (Lifeng 1994). Another account claims that the Chinese casualties were closer to 400,000 (Adelman and Shih 1993).

After the Korean War, in 1961 China and North Korea joined the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance. China and North Korea relations developed within the context of the treaty. Both nations saw their mutual defense alliance in terms of protecting their shared communist ideology, and China became a huge economic supporter of North Korea.

During the Cold War, China, North Korea, and the Soviet Union shared strong political ties and military cooperation, forming a Communist bloc against the capitalist states, notably the United States and South Korea. During the Cold War years, political similarities were the main factors that consolidated this relationship (Koo 2006).

North Korea and China continued their military relationship until the 1980s. Prior to this the relationship between these countries was fostered by frequent high-level meetings. However, a relationship once described as “close as lips and teeth” became distant and merely pragmatic as both states went through significant changes in the later 1980s and early 1990s as a result of the end of the Cold War and a rapidly changing international system. The change in this relationship was denoted in 1992 when China normalized relations with South Korea. The relationship continued to deteriorate when North Korea conducted nuclear tests in 2006 and 2009. Since these tests, China has grown increasingly perplexed and frustrated over its inability to persuade, cajole, or pressure its previous friend and ally to give up its nuclear weapons program. Moreover, China has been unsuccessful in its efforts to turn what is perceived by some as a Stalinist, developmentally backward, ideologically constrained dictatorship into a rapidly growing, relatively stable and accepted member of the international community.

Finally, China has used North Korea as a buffer zone between China and the United States (whose military forces are stationed in South Korea). This is not the only role North Korea serves for China, however, as each side considers the relationship a “friendship cemented in blood.” In this regard, China currently is focused on developing North Korea’s economy so as to maintain a stable North Korea. In response, Pyongyang has not perceived to be threatened from security and political legitimacy since both North Korea and China have shared communist system and Confucian culture.

>

SECURITY AND POLITICAL RELATIONS (SECURITY AND LEGITIMACY)

This study attempts to observe Pyongyang’s security and political relations with Beijing and its policy consequences as well as tactics. After the Korean War, China completed the last phase of the Chinese People’s Volunteers (CPV)’s withdrawal from North Korea in October 1958, but they retained a strategic interest in the Korean peninsula as the guarantors of North Korean security (Lee 1996). As a manifestation of this interest, Zhou Enlai and Kim Il Sung signed a Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance at Beijing on July 11, 1961—five days after Kim had signed a similar treaty with Nikita Khrushchev at Moscow. According to Chae-Jin Lee (1996), the Soviet Union and North Korea took the initiative in formulating the treaty with North Korea, but the Chinese also had a number of reasons for accepting the treaty.

First, the United States had revised its security treaty with Japan in 1960 in order to strengthen its military containment policy against communist countries in the Asian-Pacific region. Second, in South Korea, there was the student uprising against the Rhee Syngman government in 1960 followed by Park Chung-hee’s military coup. These disturbing events gave rise to serious uncertainty in the Korean peninsula. Third, China accepted this new treaty as a primary instrument to counterbalance not only the U.S. military presence in South Korea, but also the Soviet Union’s potential military ambitions in North Korea.

Article Two of the Sino-North Korean treaty took effect September 10, 1961.4 The Chinese worked to accommodate North Korea’s requests, openly approaching boundary negotiations, diplomatic cooperation, and economic assistance programs. The two countries in effect formed a united front against Soviet “revisionists,” U.S. “imperialists,” Japanese “militarists,” and South Korean “fascists” (Lee 1996, 60-61).

The Sino-DPRK militant friendship picked up steam when South Korea and Japan signed the Treaty on Basic Relations in June 1965 to normalize diplomatic ties, forming what China and North Korea considered to be “an anti-communist military mutual alliance.” In 1969 Mao Zedong invited Choe Young-Kun to attend the twentieth anniversary of China’s founding, and Zhou Enlai expressed enthusiasm for the “continuous growth and consolidation of the military friendship between the peoples of China and Korea” (Lee 1996, 62). In 1969, the NixonSato communiqué between the United States and Japan,5 which codified Japan’s security assurance including South Korea and Taiwan, aggravated the Sino-North Korea military alliance. A few months after the Nixon-Sato communiqué, Zhou Enlai visit to Pyongyang to fortify bilateral military alliance. Zhou announced the Nixon-Sato communiqué a “new U.S.- Japanese military alliance spearheaded against the peoples of Asia” and unequivocally stated.6

Also, Zhou and Kim signed a joint communiqué on April 7, 1970.7 After Zhou’s visit to Pyongyang, China and North Korea agreed upon a package Chinese economic aids, including technical cooperation aids, long-term commercial transactions for Six-Year Plan of North Korea (1971-1976), and protocols on a border railway and mutual supply chain of goods. China also agreed to bolster North Korea’s military preparedness (Lee 1996). For instance, during the Cold War, Kim Il Sung adeptly exploited the Sino-Soviet rivalry to obtain substantial economic assistance from both China and the Soviet Union (Nanto and Manyin 2010).

After Hu Jinto’s inauguration in 2002, China joined the World Trade Organization and Sino-U.S. relations began to generally improve. China maintained flexibility in its North Korea policy and endeavor to suppress the North Korean nuclear program. China played a major role to host the Six-Party Talks and facilitated DPRK-U.S. negotiations. However, China fully recognized North Korea’s perceived security threat, acknowledging that the DPRK is completely surrounded by hostile countries with nuclear armament (i.e., the United States, with South Korea and Japan being under the U.S. nuclear umbrella). Beijing has chosen to make economic stability in North Korea a policy priority, leaving the United States and the international community to take the lead on denuclearization (Nanto and Manyin 2010). Although China voted in favor of United Nations Security Council (UNSC) Resolutions 1718 and 1874 sanctioning the North Korean regime for its 2006 and 2009 nuclear tests, China’s enforcement of the sanctions has been limited (Feng and Beauchamp-Mustafaga 2012). In voting in favor of Resolution 1874, the Chinese representative Zhang Yesui stressed that the sovereignty, territorial integrity, and legitimate security concerns and development interests of the DPRK should be respected and that after its return to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), the DPRK should be allowed to enjoy the peaceful use of nuclear energy. Zhang Yesui mentions that the UN Security Council’s actions should not adversely impact the country’s development or humanitarian assistance to it, and that if the DPRK complied with the relevant provisions, the UNSC would review the appropriateness of suspending or lifting the measure. He also highlight that under no circumstances should there be use of force or threat of force (United Nations Security Council 2009). China hesitated to condemn the North Korean attacks against South Korea on March 26, 2010. China even blocked discussion of the attacks in the UNSC.

Chinese Defense Minister Liang Guanglie visited Pyongyang on November 23, 2009. This trip was the initial stop on a three-nation Asian tour that included Japan and Thailand. The main objective of Minster Liang’s North Korea visit was to bring “closer friendly exchange between the Chinese and DPRK armed forces and promote exchanges and cooperation between the people and armies of the two countries.” In this trip, denuclearization was not an announced goal of the visit. North Korean General Kim Jong-Gak, the first vice director of the General Political Bureau and an influential leader in the North Korean army, visited Beijing on November 17. After the May 2009 nuclear test, these military visits revealed that the influence of the military on DPRK policy had apparently grown, leading China to reestablish communication channels with the Korean People’s Army (KPA) (

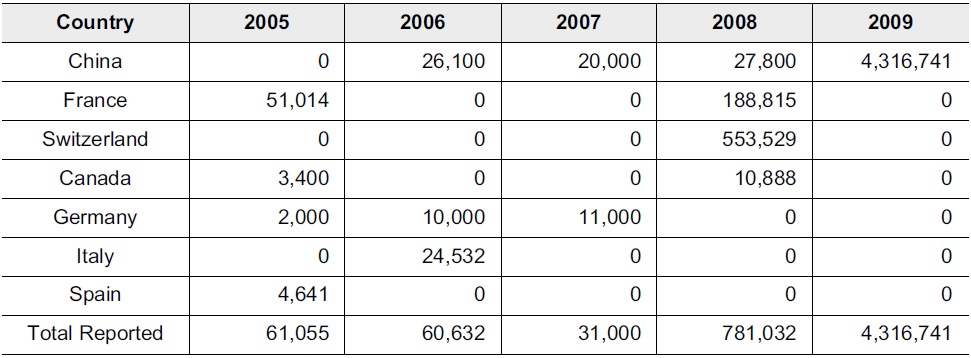

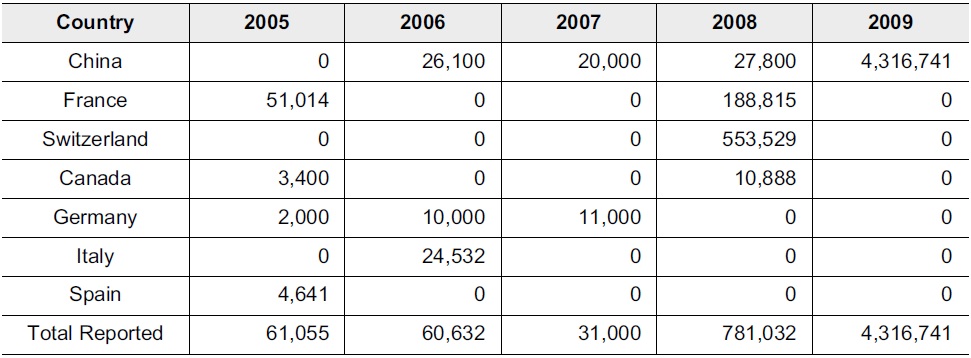

[Table 1.] Reported Exports of Small Arms to the DPRK by Country (in U.S. dollars)

Reported Exports of Small Arms to the DPRK by Country (in U.S. dollars)

On the first day of January each year, North Korea’s leaders release their annual goals in a joint editorial carried in several media in DPRK. The year 2008 was a landmark publication, the 60th anniversary of the founding of both the South and North Korean regimes. According to

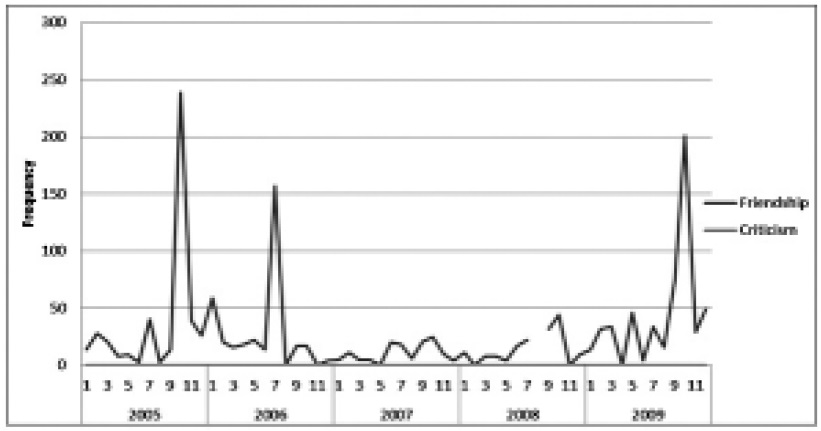

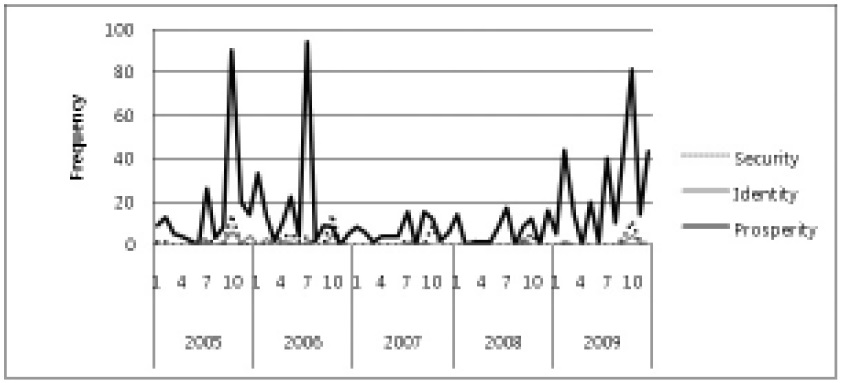

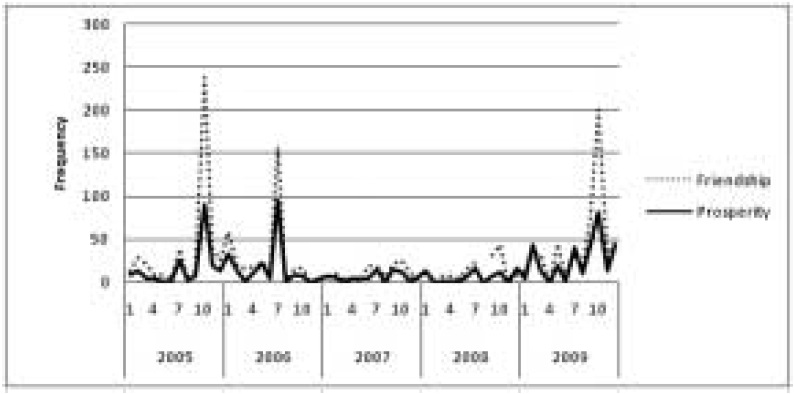

In the DPRK’s policy orientation, North Korea’s definition of “friendly countries” is derived from whether or not the country in question supports the DPRK’s ideological commitment to building a socialist fortress in North Korea, whether or not they support the DPRK’s bid for national unification, whether they join with the United States and its camp in “interfering with North Korean internal affairs” (like exerting pressure on North Korean abuse in human right issues), and whether if they will support Pyongyang’s stance in the Six-Party Talks. Only if a nation fully supports North Korea in this regard can they be treated as North Korean “friends” (Lee 2008). According to Figure 1,

July 11, 2011 marked the 50th anniversary of the Sino-North Korean “Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance” signed in 1961. Without a lavish commemoration parade in Beijing and Pyongyang, Chinese President Hu Jintao and the DPRK leader Kim Jung-Il vowed to further strengthen ties between the two states in an exchange of letters (

Since Kim Jung-Il’s sudden death in December 2011, China has behaved as expected, trying to prop up the regime in order to ensure stability in its nucleararmed neighbor. China’s foreign ministry sent a message of strong support for Kim Jung-Un, Kim Jung-Il’s successor, and encouraged North Koreans to unite under the new leader. After the North Korea’s third nuclear experiment in February 2013, Choe Ryong-Hae, a special envoy from North Korea, met Chinese President Xi Jinping in Beijing. He delivered Kim Jung-Un’s personal letter to improve ties with China against South Korea and the United States (

>

THE DPRK’S ECONOMIC RELATIONS WITH CHINA

With regard to regime survival and economic development, North Korea still tried to maintain indispensable relations with China. China and the Soviet Union provided military assistance to North Korea during the Korean War. Until the early 1990s, both countries provided the DPRK with its most important trade markets, were its major suppliers of oil and other basic necessities, and provided reliable diplomatic and political assistance. Since the disintegration of the Soviet Union, China has been North Korea’s largest economic trading partner and provider of humanitarian aid. However, the demise of the Soviet Union and the former communist bloc in Eastern Europe, combined with the gradually warming relationship between Beijing and Seoul, significantly altered Pyongyang’s ties with Beijing and Moscow.

North Korea’s decision to favor heavy industry over light industry following the Korean War in the 1950s was the first fatal mistake that ultimately lead to the DPRK’s economic downfall. The recent cause of North Korea’s precipitous economic decline is also linked directly to the evaporation of decades of food and energy support from long-standing allies, which began as early as 1990. The situation was subsequently worsened by severe flooding in 1995 and 1996. The declining food situation is only one aspect of North Korea’s failing economic system. Other parts of the economy are also faced with a similar situation. With the cessation of subsidies in grain, energy, and fertilizer from old allies, North Korea’s agricultural production dropped by almost 50% from the late 1980s to a low of 2.5 to 2.6 million tons in 1995. Despite the major economic crisis threatening its very survival, the North Korean regime has been downplaying the severity of the situation, pretending as if the whole thing was concocted by western countries for propaganda purposes. With the possible exception of North Korea’s efforts to promote the Rajin-Sonbong Economic Zone, North Korea has been slow to react to its own economic crisis. It has refused to accept Chinese suggestions to reform its economy along Chinese lines.

In some extreme cases, however, it has reluctantly applied “Band-Aid” fixes. According to Snyder, one such ‘Band Aid fix’ was

While all this was going on, North Korea lost its dear leader Kim Il Sung. To express its disagreement with North Korea over the nuclear program, China did not send an appropriate delegation to express its condolences. With China distancing itself from North Korea, the north suddenly found itself virtually alone. Left with no choice, it thus followed a continuing path of isolationism (Singh 2004).

After a three-year period of self-exclusion, North Korea finally returned to the international scene. It first attempted to amend its relations with its traditional ally, China. In 1998, Pyongyang proposed that economic development was fundamental to achieving a strong and prosperous nation that could tide over domestic disasters, economic difficulties, and sparse relations with the international community (

However, China currently is focused on developing North Korea’s economy so as to maintain a stable North Korea. China has become North Korea’s largest trading partner and the largest investor in North Korea (Lee 2009). North Korea and China have been transforming their relationship from a military alliance to a more pragmatic one focused on pursuit of their economic needs (Lee 2010).

In terms of Pyongyang’s economic reform, for the purpose of economic development under the North Korean style socialism, North Korea adopted a “Chinese economic model” in order to overcome its economic deadlock. In Pyongyang’s economic development policy, Park (2002) stresses “North Korea may have already decided to develop its economy through a strategy patterned after the Chinese model.” As long as China believes the partnership helps maintenance of a stable and peaceful international environment in its neighboring regions, the economic development assistance and cooperation will remain in effect.

Conclusively, through mutual economic cooperation with China, Pyongyang has adopted a sustained economic strategy influenced by the “Chinese model” while maintaining “Korean style socialist system” (

4Article Two was declared: “The Contracting Parties undertake jointly to adopt all measures to prevent aggression against either of the Contracting Parties by any state. In the event of one of the Contracting Parties being subjected to the armed attack by any state or several states jointly and thus being involved in a state of war, the other Contracting Party shall immediately render military and other assistance by all means at its disposal” (Peking Review 1970). 5China also was eager to strengthened military alliance with North Korea because the Chinese were interrupted by the joint communiqué signed with President Richard M. Nixon and Prime Minister Sato Eisaku on November 21, 1969. This communiqué declared “the security of the Republic of Korea was essential to Japan’s own security and maintaining peace and security in Taiwan was most important for the security of Japan” (Lee 1996, 63). 6See the Zhou’s speech at the Banquet invited by Kim Il Sung (Peking Review 1970, 13-14). 7See “The joint communiqué of the Sino-North Korea” (Peking Review 1970, 3-5). 8When the Premier of PRC, Wen Jiabao, met Kim Jong-Il in October 2009, he offered Kim JongIl to visit China (Chosun Ilbo 2010). 9Expressed and ‘amities’ and criticisms’ words are counted as an item friendship and criticizing China in Rodong Sinmun: Amicable Words - “friendship” (Chinsun; Wooho; Sunrin), Criticism Words - “enemy” (wonsu), “puppet regime” (gyerae), “cabal Party,” “Gang Group,” “Thief Group” (paedang; ildang; dodang), “Traitor; treason” (maeguk; banyeok; yeokjeok), “fasicist” (fashow), “submission” (sadae).

NORTH KOREA’S POLICY PRIORITY TOWARD CHINA

After the demise of the Socialist bloc, the North Korean leadership sought to learn from the experience of the Chinese leaders who had developed the economy while maintaining the authoritarian rule of the communist party. After the revision of the North Korean constitution by Kim Jung-Il in 1998, Pyongyang tried to adopt a progressive “omni-directional foreign policy” to address the economic difficulties resulting from their isolation. Kim Jung-Il also revealed a new political vision for his regime known as

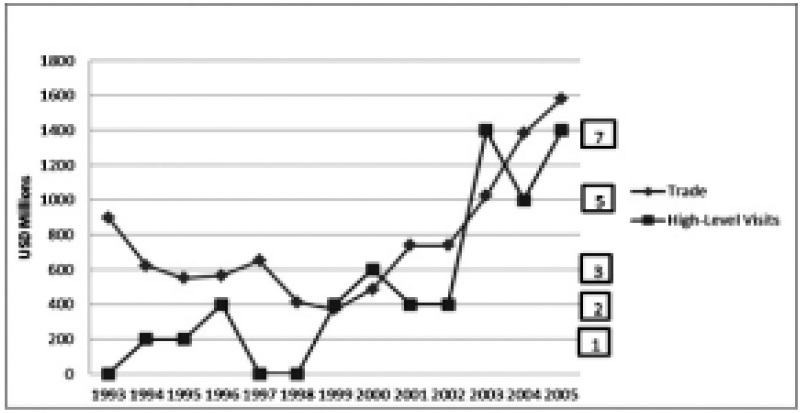

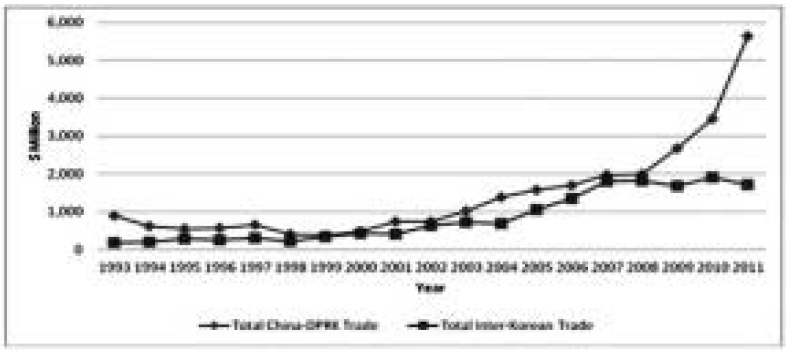

China was likely afraid of the collapse of the North Korean regime, seeing as the DPRK had long been viewed as a strategic buffer zone against U.S. forces in South Korea. Therefore, Chinese leadership hoped North Korea would adopt the Chinese model, along with the Chinese Northeast economic development project (Kim 2010). In August 2001, President Jiang Zemin of China visited North Korea and offered increased humanitarian aid and economic assistance. In October 2005 and January 2006, Hu Jintao and Kim Jung-Il made reciprocal visits between the two countries. These visits reaffirmed their amicable relationship and allowed for further discussion of North Korea’s nuclear programs and the ongoing economic cooperation between the two nations. The increase in highlevel interaction brought along strengthened trade and investment relationships between China and the DPRK. Figure 2 indicates a rough correlation between bilateral trade and the frequency of high-level dialogues between China and the DPRK (Snyder 2009).

Furthermore, when North Korean Foreign Minister Paek Nam-Sun visited Beijing in May 2006, the Chinese leaders suggested providing massive economic aid to North Korea if the Six-Party Talks resumed. This economic assistance included massive investment of Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs), political loans, and establishment of an industrial complex (Kim 2010). Unfortunately, this aid was never actually provided to North Korea because North Korea conducted a nuclear test in October 2006. However, when Chinese Premier Wen Jiobao visited Pyongyang to celebrate the sixtieth anniversary of diplomatic relations between Sino-DPRK on October 4, 2009, Pyongyang signed additional documents reasserting their mutual economic and technological cooperation with China (Nanto and Chanlett-Avery 2010). According to

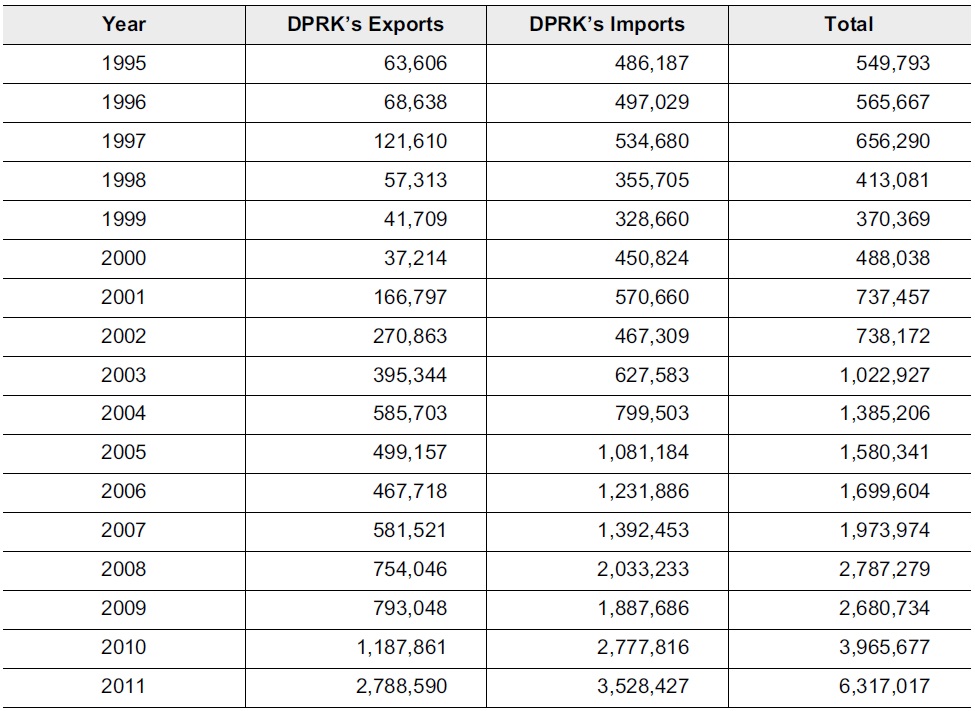

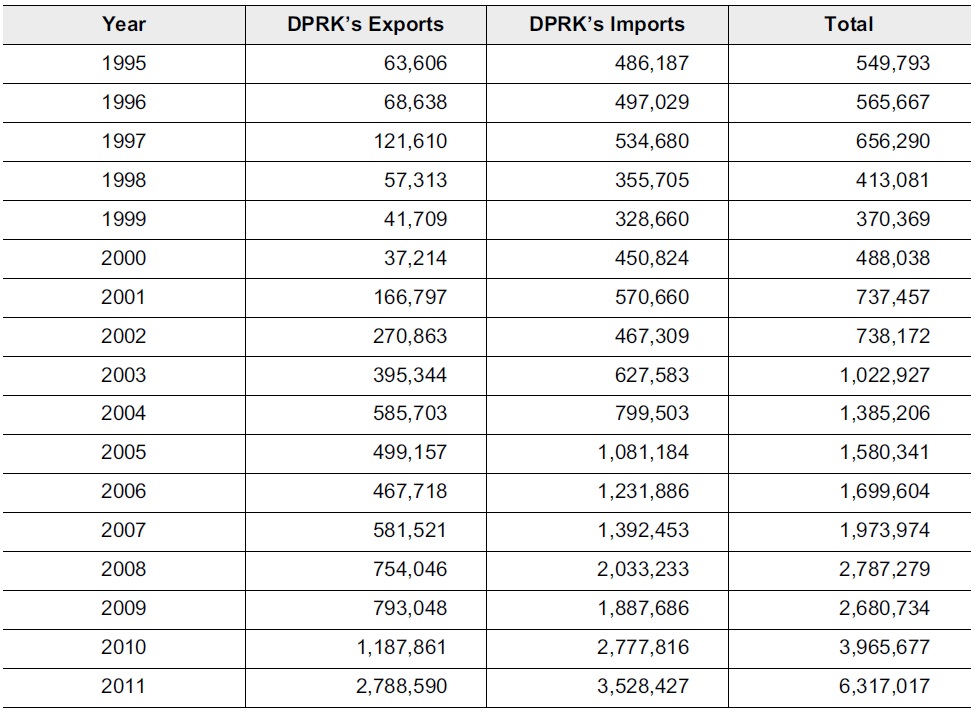

The DPRK’s missile and nuclear tests in 2006 and long-range missile test in April 2009, as well as the second nuclear test in May 2009, added tension to relations with the United States, South Korea, Japan, and even China. After Pyongyang’s long-range missile test in April 2009, China agreed to stronger UN sanctions toward North Korean companies. Also, after Pyongyang’s second nuclear test in May 2009, China condemned North Korea in June 2009 and supported UN Security Council Resolution 1874, which carried additional sanctions against the DPRK. North Korea still imported luxury goods estimated between $100 million to $160 million from China in 2008, even under UN sanctions.10 North Korea continues to use air and land routes through China with little risk of inspection, and luxury goods from China and from other countries. It shows that China takes a minimalist approach to implementing sanctions against North Korea (Nanto and Manyin 2010). As shown in Table 2, merchandise trades from China to North Korea continued to increase, even after the UN economic sanctions of 2009. In November 2009, China announced a new economic development zone (the

[Table 2.] The DPRK’s Merchandise Trade with China, 1995-2011 (Unit: USD, thousand)

The DPRK’s Merchandise Trade with China, 1995-2011 (Unit: USD, thousand)

In spite of strong warnings from the international community, Pyongyang conducted a nuclear test on May 25, 2009. After the second nuclear test, the UN reproached North Korea with the passage of UNSC Resolution 1874. North Korea’s nuclear armament policy has resulted in further isolation from the international community and international markets. To make things worse, South Korean president Lee Myung-bak (2008-2012) adopted a hardline policy toward North Korea. Pyongyang has worked to adopt the Chinese economic model as an extension of Kim’s

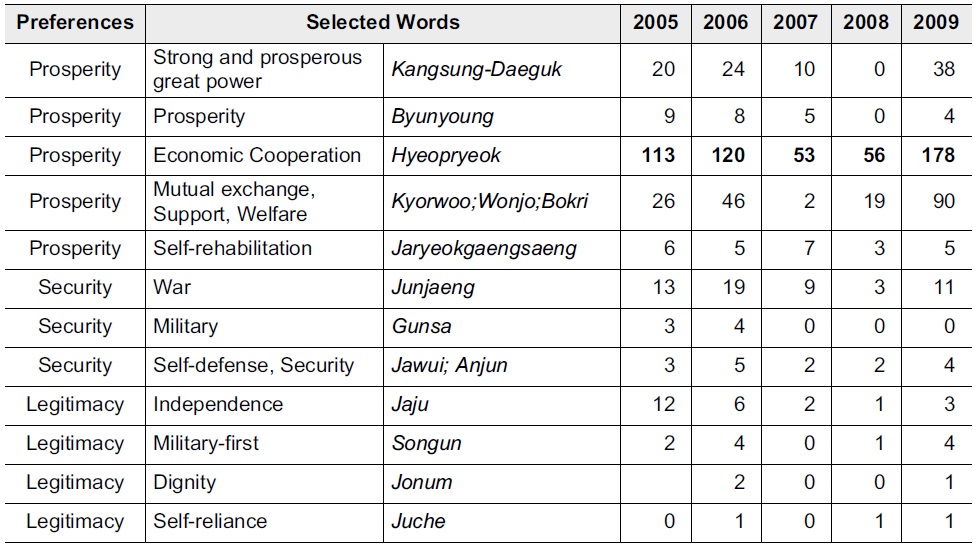

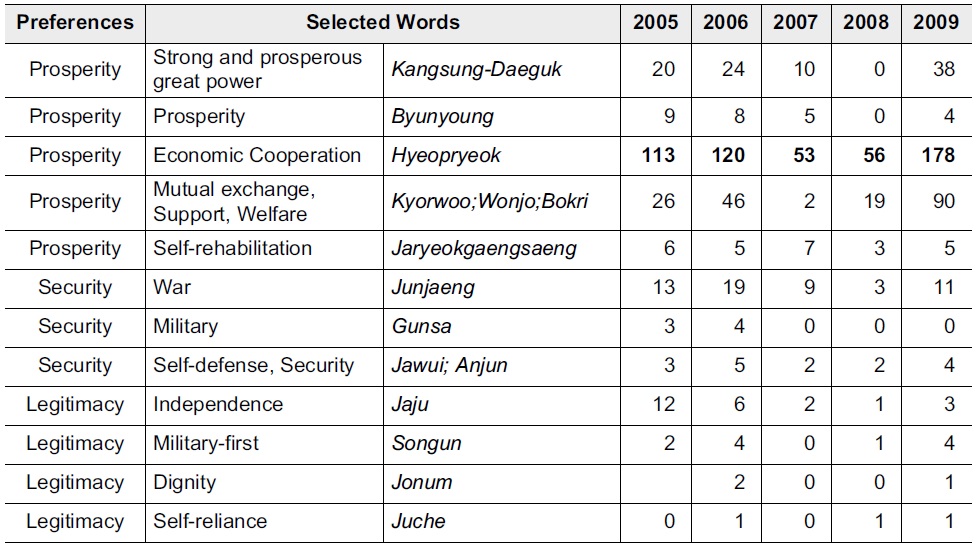

Along with some objective observations, this study examines the policy priority of the DPRK’s regime through content analysis. As mentioned before, this study primarily employs

[Table 3.] The Selected Word’s Frequency for the DPRK’ Policy Preference to China, 2005-2009

The Selected Word’s Frequency for the DPRK’ Policy Preference to China, 2005-2009

The role of China is regarded as the most important external factor in dealing with the DPRK. Even though Pyongyang is deadlocked in economic isolation from the western world and South Korea has adopted new, hardline policies in response to the development of North Korea’s nuclear capabilities, China’s cooperation has fortified North Korea both economically and ideologically. Beijing has maintained this relationship as a means of preserving the existing security order in East Asia. The Sino-DPRK relationship is mutually advantageous.

In short, North Korea has continued its “blood-ties relationship” in military, ideological, and social terms with China. Over time, however, North Korea’s foreign policy toward China has become less about military alliance and more about pragmatic economic relations. According to Table 3 and Figure 4, these analyses support the hypothesis that Pyongyang’s foreign policy toward China is overwhelmingly influenced by the desire for economic prosperity.

10According CRS report, in 2009, North Korea’s major exports to PRC included mineral fuels (coal), ores, woven apparel, iron and steel, fish and seafood, and salt/sulfur/earths/stone. DPRK imports mineral fuels and oil, machinery, electrical machinery, vehicles, knit apparel, plastic, and iron and steel from China. Also, China is a major source for DPRK imports of petroleum. From Chinese data, in 2009 exports to the DPRK of mineral fuel oil totaled $327 million and accounted for 17% of all Chinese exports to the DPRK (Nanto and Manyin 2010). 11It counts the frequency of proper nouns regarding with security concern, identity needs and economic prosperity toward China in Rodong Sinmun from 2005-2009: 1) Security words - “war (Jyeonjaeng)”; “military (Gunsa),”; “self-defense (Jawoi)”; “security (anjun)” 2) National Identity words - “self-reliance (juche)”; “military-first (sungun).” 3) Economic Prosperity words - “economic self-help (jaryeokgaengsaeng)”; “prosperity (byunyoung; kangsungdaekuk).”

North Korea’s foreign policy orientation has evolved in pursuit of the systematic goals of national security, national identity or legitimacy, and economic prosperity. Pyongyang’s policy for Beijing is oriented toward “economic prosperity” as a means of alleviating difficulties caused by natural disasters and UN sanctions. Even though China condemned the North Korean nuclear tests and long-range missile launches and agreed to sever UN economic sanctions, North Korea imports luxury goods through Chinese channels and does significant commercial trade with China’s SOEs. Since 2008, South Korean has forced an increase of North Korea’s economic dependence on China. Pyongyang has adopted the Chinese economic model while maintaining Korean-style socialist system (

As shown in this article, whenever Pyongyang needs economic cooperation and aid, North Korean policy emphasizes strongly on friendship with Chinese leaders and organizes bilateral high-level talks. In addition, after the recent execution of Jang Song Thaek, China has remained largely silent on the execution; but when asked about the matter at a press conference on December 13, Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson Hong Lei diplomatically stated: “We have noted relevant reports. It is the DPRK’s internal affair. As its neighbor, we hope to see the DPRK maintain political stability and realize economic development and people there lead a happy life” (

Finally, this study reveals that Pyongyang’s priority for the Chinese policy has relied overwhelmingly on “economic prosperity.” In addition, it is likely that Kim Jong Un is not expected to compromise on North Korea’s nuclear program despite China’s pressure as long as Pyongyang is under security and economic blockade from Washington and Seoul, as Pyongyang’s leaders recognize Beijing would not tolerate the collapse of North Korea’s communist regime to maintain the status quo with the United States in East Asia. In this sense, Pyongyang under Kim Jong Un is likely to expand the strategic economic cooperation with Beijing in order to alleviate North Korea’s economic difficulties while maintaining his predecessors’ political system. Therefore, there are no significant changes to North Korea’s policy orientation toward China.

12China’s Vice Foreign Minister Liu Zhenmin (劉振民) visited Pyongyang and Seoul in February 2014.