Two of the most important trends in the global economy in recent decades have been (1) the dramatic increase in the role of information-intensive products (e.g., various types of computer software products, consumer electronic products and IT-related services), and (2) the proliferation of trade liberalization through both economic integration and preferential trade agreements. Advances in both digital technology and trade liberalization have driven an increase in the flow of information-intensive products across countries.1

As a result of these changes, consumers face an international array of competing product groups based on incompatible, proprietary standards.2 The choices among computer operating systems, television broadcasting standards, and DVD systems are recent examples. In addition, it is widely recognized that products based on the same industrial standard exhibit an indirect network effect: the utility of consumers is increasing in the variety of complementary products based on a particular standard.3 Trade liberalization matters in this context because it reduces import prices, and changes (usually enlarges) the available sets of complementary products, thus influencing a society’s patterns of consumption.

In such settings, competition between a ‘domestic’ standard and a ‘nondomestic’ standard is often observed. A recent example is the global competition among wireless telecommunications service providers. Funk (1998) suggests that, although most service providers are likely to dominate domestically and thereby make the ‘home’ standard dominant, firmssuch as Motorola, Ericsson, and Nokia have succeeded in marketing a ‘non-domestic’ standard. He suggests that, while Motorola USA’s market share in Europe is lower than in its domestic market, it still holds a significant position in the European (and therefore theworld) market.4 Another famous example involves incompatible color television standards. It is widely believed that incompatible standards for color television (i.e., the NTSC system in the US and Japan; the PAL system inWestern Europe) have contributed significantly to Japanese firms’ lower market share in Western European markets relative to the US market.5 There seems to be a case for closer examination and more formal modeling of increased trade in technology-related products and fiercer competition among incompatible industrial standards.

In the literature on trade and competing industrial standards, the role of government standardization policy is often emphasized. In their influential contribution, Gandal and Shy (2001) analyzed governments’ incentives to recognize foreign standards when there are potentially both network effects (i.e., consumption benefits) and conversion costs. Their focus was on how standardization policy affects both international trade flows and national welfare.

An important question about the relationship between competing industrial standards and trade liberalization remains unanswered: how does trade liberalization affect consumers’ choice between incompatible standards? The main purpose of this study is to illustrate, with simple trade theory, this relationship. Following Matsuyama (1992), we assume that there are two incompatible standards, each of which applies to a group of differentiated products. A product can be used only in combination with other products based on the same industrial standard. Matsuyama assumed a closed economy and paid scant attention to the role of trade liberalization. In contrast, in this study we focus on the case of competing industrial standards in an international context (i.e., a Home standard and a Foreign standard) and examine the impact of trade liberalization (i.e., a decline in trade costs) on consumers’ choice of a standard.

The structure of this paper is as follows. In the next section we present a basic model: assuming that products are only consumed in a single (i.e., Home) country,we consider the competition between the Home standard and the Foreign standard. Based on this basic model, in Section 3, the impact of unilateral trade liberalization (i.e., a decrease in trade cost on Foreign products in the Home country) is considered. In Section 4, we extend the basic model to the case of twosegmented (i.e., Home and Foreign) markets, and the impact of bilateral trade liberalization is considered. Concluding remarks are presented in Section 5.

1Addressing this point, the OECD (2006: Ch. 2) reports that between 1996 and 2004 the annual increase in OECD countries’ exports of ‘software goods’ was 5%, while imports increased by an average of 6.5% per year. 2In this study we will use the term ‘standard,’ not in the sense of government regulation, but in the universal sense of the set of technical specifications that enable compatibility among products. 3The seminal contributions on the indirect network effect are by Chou and Shy (1990) and Church and Gandal (1992). See Gandal (2001, 2002) and Farrell and Klemperer (2007) for surveys of the relevant literature. In the international context, see Iwasa and Kikuchi (2008) and Kikuchi (2005, 2007) for analyses of trade liberalization in the presence of network effects. 4Motorola’s share of the world market dropped from 40% in 1994 to 32% in 1995, as use of the European GSM standard grew. Still, it is larger than Nokia’s share in the world market (22%). See, also, Lembke (2002). 5Burton and Saelens (1987, p. 291) note that, while sales by Japanese firms accounted for 43.5% of all sales in the US market in 1981, Japanese firms held only a 15.2% share of theWestern European market in 1983. (Note that the Japanese televisions that are exported to the Western Europe are based on PAL system.) Rohlfs (2001) discusses this in terms of network effects.

Suppose that there are two countries, Home and Foreign. In this and the next section, we concentrate on what happens in the Home market. Both Home firms and Foreign firms compete in the Home market, which is defined as a line of unit length representing consumers’ set of preferences. Home consumers are indexed by

Assume that there are two competing industrial standards:

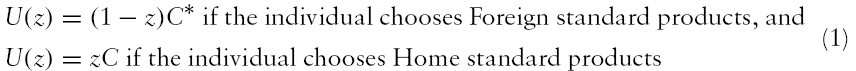

Each consumer is assumed to purchase products based on only one standard (Home or Foreign). We call the two groups of differentiated products Home standard products and Foreign standard products. The utility of consumers is assumed to be increasing in the variety of complementary products based on a particular standard. We define the utility of an individual of type

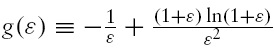

where

where

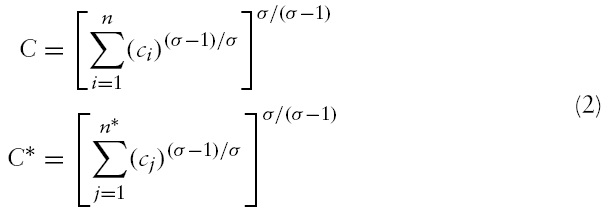

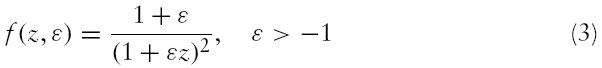

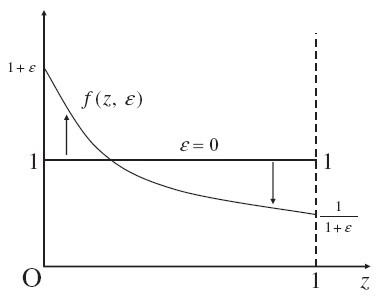

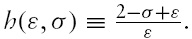

Following Chou and Shy (1996, p. 314), we assume that the density function of consumers’ types is given by,

when

The importation of Foreign products is inhibited by frictional trade barriers, which are modeled as iceberg trade costs: for 1 unit of Foreign product to reach Home,

where

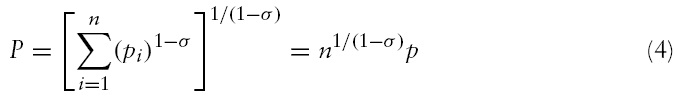

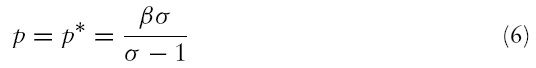

Let us turn to the cost structure of differentiated products. In order to simplify the argument, technology is assumed to be identical between countries and characterized by increasing returns to scale, since both product creation and market entry typically involve fixed costs.7 We denote the constant marginal cost of production for every product by

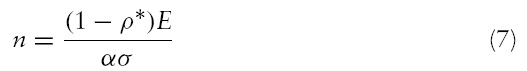

Let us denote the number of consumers who purchase Home (resp, Foreign) standard products as

Combining equations (4), (5), (7), and (8), it can be easily shownthat a consumer’s welfare increases when more consumers purchase products with the same standard. As more consumers choose the same standard, more firms choose to produce based on that standard. This results in increased product diversification among products with that standard.

This results in the types of ‘indirect network effects’ analyzed by both Chou and Shy (1990) and Church and Gandal (1992): network effects work indirectly via increased diversification of products (see Gandal, 2002).

Now let us turn to the equilibrium number of consumers who purchase Home/Foreign standard products. We denote by

the type of the marginal consumer who is indifferent between two standards. Using equation (1),

is derived as

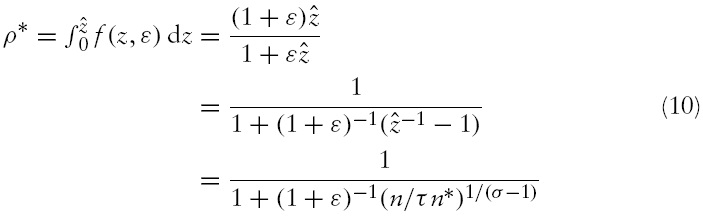

The equilibrium number of consumers who purchase Foreign standard products,

as follows:

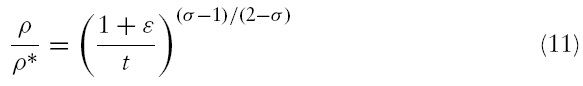

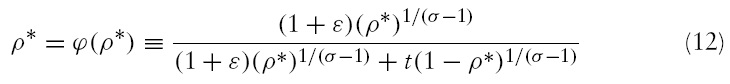

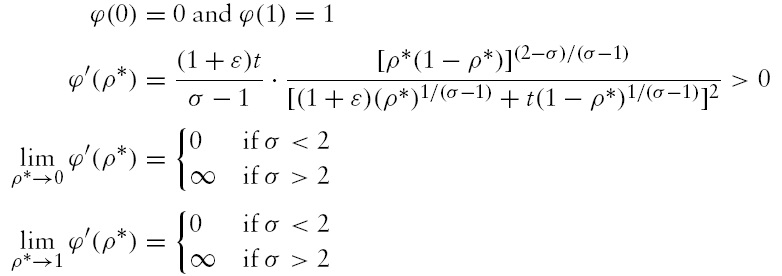

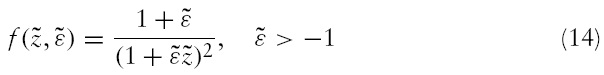

Substituting in the equilibrium number of differentiated products, we can obtain the equilibrium proportion of consumers who purchase Home standard products:

6See Matsuyama (1992) for elaboration on this point. This assumption implies that, for one country’s producers, the cost of converting to the other standard is extremely high. Although this assumption is restrictive, it is often argued that the existence of (high) conversion costs affects foreign firms’ behavior (Gandal & Shy, 2001). 7As a first step to incorporate competition between industrial standards, we will concentrate on the case of identical technology between standards. In order to analyze the interaction of technology gap and standard competition, an extension for asymmetric technologies needs further consideration. 8For discussion on the role of market entry in the presence of fixed costs, see Melitz (2003).

3. The Impact of Unilateral Trade Liberalization

In this section we consider the impact of unilateral trade liberalization (i.e., a reduction in

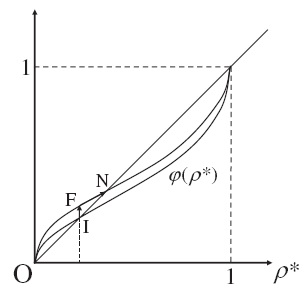

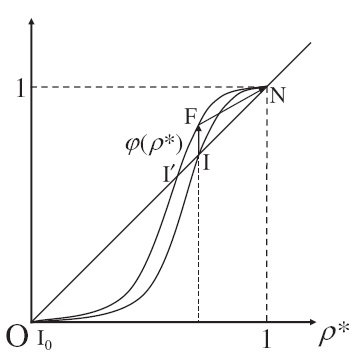

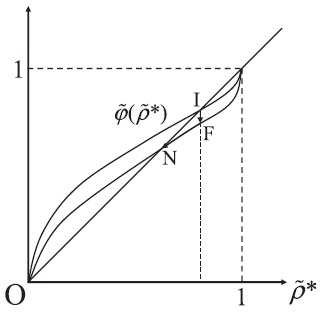

Figures 2 and 3 help to illustrate the trading equilibrium. The curves represent

These results indicate that, depending on the level of elasticity between varieties,

First, it is important to note the multiplicity of equilibria. Clearly from Figures 2 and 3, there are three possible equilibria in each case: two corner solutions (only Home (or Foreign) standard products exist) and an interior equilibrium where both standard products coexist. If the economy initially stays at the corner solution, a reduction in trade costs does not affect the equilibrium configuration. Thus, in what follows, we concentrate on the interior equilibrium where both standard products initially coexist.

When

The point is that there is a cumulative process in which trade liberalization will enhance Home consumers’ propensity to switch to the Foreign standard, and this switching will induce further product diversification among Foreign products. Still, since the indirect network effect is mild, some consumers who prefer Home standard products continue to choose those products.

This result is also quite important from the welfare perspective: since trade liberalization leads some Home consumers to ‘switch’ to the Foreign standard, the market size for Home standard products will shrink and consumerswho continue to choose Home standard products are made worse off by trade liberalization.

It is important to note that the result that some consumers are made worse off by trade liberalization is not newin trade literature as Heckscher–Ohlin and other competitive models show. However, our results are derived from an imperfectly competitive setting.

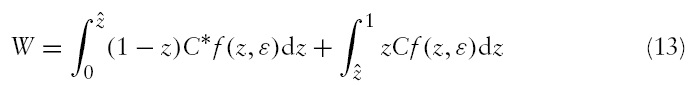

Next, let us consider the changes in total consumers’ welfare, which is defined as follows:

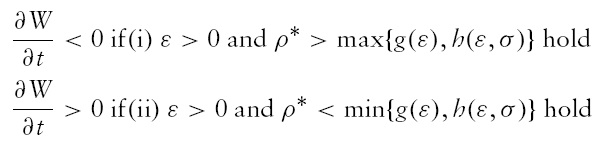

Differentiating

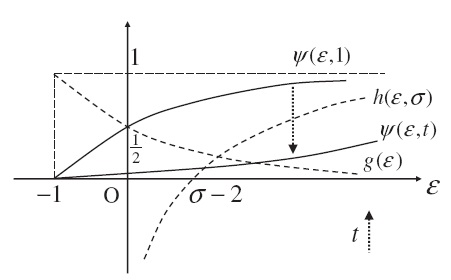

Figure 4 helps to illustrate the relationship between

Proposition 3 (condition (i)) implies – given that the Home consumers’ preferences are biased toward Foreign standard products and the initial share of Foreign standard products is sufficiently large – that trade liberalization increases total Home welfare. Thus, although some consumers who continue to choose Home standard products will be made worse off by trade liberalization (Proposition 2), one can find a redistributive scheme that makes nobody in Home worse off. As space is limited, we have concentrated on the changes of total consumers’ welfare and paid scant attention to the redistributive scheme.11

When 2>

In case (2a), the initial trading equilibrium is obtained as point I0 in Figure 3. In this case, although trade liberalization reduces the price of Foreign standard products, Home consumers continue to choose Home standard products. This is because of strong indirect network effects: consumers have a strong incentive to purchase a product with large product diversification.

This result is quite important for considering the relationship between the level of trade costs and the amount of imports. For example, careful analysis of Japan’s trade volume during the 1980s suggests that Japan imports only about half as much as one would expect.13 Our result suggests that, given the existence of strong indirect network effects, one country’s consumers may stick with their own country’s standard products even though trade is liberalized.

In case (2b), the initial trading equilibrium is obtained as point

A comparison between these three cases (1, 2a, 2b) highlights the important role of indirect network effects. On one hand, if the indirect network effect is mild, trade liberalization makes the Foreign standard more attractive to some extent. Still, some consumers who prefer Home standard products continue to choose them. On the other hand, if the indirect network effects are sufficiently strong, the effects of trade liberalization are crucially dependent upon the initial situation. Given that initially there are no Foreign standard products (2a), trade liberalization has no effects on trade flows. Instead, given the coexistence of both standard products (2b), trade liberalization will take Home standard products completely out of the Home market.

9From equation (11) we obtain which gives the value of ρ∗ corresponding to the interior equilibrium. Note that limε→−1+0 ψ(ε, t) = 0, limε→∞ ψ(ε, t) = 1, ∂ψ(ε, t)/∂ε>0, and ∂ψ(ε, t)/∂t<0. 10Figure 4 indicates that, the smaller (resp. larger) t becomes, the higher the possibility of (∂W/∂t)<0 (resp. (∂W/∂t)>0) becomes. 11For this point, see, Kemp and Shimomura (2001) and Fujiwara (2005). 12In case (2c), since there are only Foreign standard products, trade liberalization does not change the nature of trade flows. 13See Lawrence (1987). 14It is important to note that point I is unstable. One interpretation of this situation is as follows: suppose that initially σ is sufficiently close to (but larger than) 2 for the point I to be stable. Then, some parameter change increases σ, which changes the slope of the ϕ curve. In this situation, at least initially, the economy might stay at point I. Thus, the results in case (2b) need to be interpreted with great caution. 15Another possible equilibrium is point I´. However, since potential Foreign firms enter due to improved access to the Home market and more consumers switch to Foreign products, it seems to be natural that point N will be selected as the new equilibrium.

4. The Impact of Bilateral Trade Liberalization

Now consider the case markets with both a Home market segment and Foreign market segment.To simplify the argument,we concentrate on the case inwhich the degree of indirect network effects is mild (i.e.,

is normalized to 1.16 Assume that consumers’ taste in Foreign market is represented by equation (1). We assume that the density function of consumers’ types in the Foreign market is given by,

The only difference is the distribution of consumers’ tastes: since a larger value of

holds. In the Foreign market, the price of an imported Home standard product will be

while that of a (domestic) Foreign standard product will be

where

is the number of consumers who purchase Foreign standard products in the Foreign market.

We should notice that the fixed market entry cost is market-specific: the producers of Home (resp. Foreign) standard products, which have been paid market entry cost for its own market, have to pay additional market entry cost when they decide to export to Foreign (resp. Home) market. This implies that the numbers of Home and Foreign standard products in each market are determined independently

17

Following the same procedure as in the Home market, we can obtain the equilibrium relationship for the number of consumerswho purchase Foreign standard products in the Foreign market:

Figure 5 helps to illustrate the impact of bilateral trade liberalization. If both

become smaller,

shifts downward. Thus, while the number of Home standard products becomes smaller in the Home market (i.e.,

This implies that the degree of intra-industry trade of non-domestic standard products will be increased by bilateral trade liberalization.

Let us consider this proposition more precisely. In each country, with the increased effective number of non-domestic standard products, consumers begin to switch to those products. Such switching will provide opportunities for the entry of non-domestic standard producers.As with Proposition 1, the point is that there will be a cumulative process in which bilateral trade liberalization encourages consumers to switch towards non-domestic standard products, and those switchings will induce further intra-industry trade of non-domestic standard products.

16We use ‘∼’ to denote Foreign market values. 17This approach relates to that of Melitz (2003). In an alternative approach, one can assume that the fixed costs are paid only once. Then, the equilibrium number of products is obtained by adding both markets’ demand conditions. Although that approach is desirable, deriving explicit solutions from such a system of simultaneous equations might not be feasible. An extension for this setting needs further consideration. We would like to thank one referee for pointing this out.

Both trade liberalization and advances in digital technology have intensified competition between incompatible industrial standards. In this study, we explained the mechanism by which trade liberalization influences consumers’ choice of a standard. In Sections 2 and 3 we examined the impact of unilateral trade liberalization in a single (i.e., Home) market. It should be emphasized that the degree of substitution between product varieties plays an important role in determining the impact of trade liberalization: if the degree of substitution is sufficiently small (i.e., the indirect network effect is relatively large) and both standard products coexist before trade liberalization, trade liberalization will take Home standard products completely out of the Home market. In Section 4, we examined the impact of bilateral trade liberalization in a setting with two segmented markets. It was shown that the intra-industry trade of non-domestic standard products will be increased by bilateral trade liberalization.

This result (increased intra-industry trade due to trade liberalization) is not so new.18 However, we would like to emphasize that the cumulative process of consumers switching and firms enteringworks as a driving force behind the increased intra-industry trade. This point has not appeared in the existing literature.

The present analysis must be regarded as tentative. Hopefully, it provides a useful paradigm for considering how trade liberalization affects international competition among industrial standards.

18See, for example, Helpman and Krugman (1985).