The Korean growth miracle is fundamentally the story of the growth of industry. From a starting point following the period of colonial occupation and civil war where industry produced little and exported less, manufacturing grew rapidly for four decades. The reallocation of labor from low-productivity agriculture to high-productivity manufacturing explains a substantial fraction of the growth of labor productivity in Korea in the second half of the twentieth century, and especially in the early portion of the high-growth period.1 And it makes sense that the Korean economy should have become a net exporter of manufactured goods insofar as the country is necessarily a net importer of agricultural goods and raw materials, reflecting its limited endowment of fertile land and resources.2

But none of this was preordained. Korean industrialists, in order to compete successfully, had to solve a number of specific problems. Compared with agriculture and services, industry is more capital intensive; growing industry thus requires mobilizing finance for investment. Industrial production is characterized by economies of scale. That is, in addition to using a relatively high ratio of capital to labor, industrial firms use large absolute amounts of capital. Capital requirements therefore exceeded what any one individual or family can provide. A relatively high minimum efficient scale also means, particularly in small, less developed economies, that growth will be constrained by the size of the market unless firms succeed in exporting. Finally, manufacturing requires specialized inputs, which the firm itself or one of its suppliers must provide. Here too the capital intensity of production comes into play, for a disruption to the provision of those inputs can have debilitating costs if an expensive capital stock is forced to sit idle.

These are not problems that arms-length markets automatically solve. Aspiring entrepreneurs, lacking reputation and collateral, may find it hard to access external finance on the requisite scale. Outside investors, fearing that their funds will be diverted by those in control, may hesitate to lend. Industrialists requiring specialized inputs may hesitate to rely on third parties, fearing that they will be held up. Producers lacking commercial contacts may find it hard to break into export markets.

Here three obvious solutions suggest themselves: government, business groups, and financial institutions. Government can mobilize capital. It can substitute its reputation, and its collateral in the form of its power to tax, for the reputation and collateral of private borrowers, providing firms with external finance and insurance against risk. It can coordinate investments in capacity in complementary industries, all of which must be up and running in order for any to succeed. Bureaucrats can supplement or, in the limit, substitute for other sources of managerial expertise. Government can provide consular and commercial services to help producers break into international markets.

Business groups are another solution. Groups can form through repeated contact giving rise to long-term relationships or from the simple fact that control of each of the constituent firms is in the hands of the same economic coalition, often members of the same family. With family ties guaranteeing good faith, cash-rich firms can provide finance for not yet profitable affiliates. Otherwise prohibitive risks of doing business in sectors where capital requirements are high but finance is uncertain can be managed through intra-group transfers, either directly or via a bank that is a member of the group. And when the firms in question are members of the same business group, they can outsource the production of specialized inputs without fear of being held up.

Financial institutions are a third solution. Banks can mobilize the capital of small savers. They can invest in monitoring technologies to screen loan applicants and determine which ones possess attractive investment projects. Venture capital firms can combine specialized technological knowledge with financial expertise to fund start-ups with unfamiliar technologies. Banks as large investors occupy seats and possess a substantial fraction of votes on corporate boards, enabling them to advocate on behalf of outside investors.3 Sometimes (in the case of Germany, for example) the same bank sits on the boards of different companies in up- and downstream industries, solving coordination and hold-up problems.

None of these solutions is perfect, and there may be circumstances in which their costs exceed their benefits.Government functionaries lack the high-powered incentives of owner-managers who stand to reap enormous returns from correct decisions.They lack the specialized knowledge and talents of thosewho have risen to the top through the process of natural selection known as market competition. The businesses they support may operate as if facing soft budget constraints, expecting to be bailed out of losses. They may make decisions on the basis of non-economic objectives at odds with the pursuit of efficiency.4

Business groups can similarly be a source of inefficiency. Horizontal groups whose members do business mainly with other members will be insulated from competition. Groups with captive banks may be freed of having to compete for funds. Both arrangements may allowinefficient practices to persist. Such observations are the basis for complaints that big business groups are slowand lumbering. In addition, groups organized as pyramids, with the firmat the top owning a controlling interest in the next tier of firms, each of which owns a controlling interest in a next tier of firms, may widen the gap between ownership and control, aggravating agency problems. The controlling family may divert resources provided by outside investors. It may engage in ‘tunneling,’ transferring resources from firms in which it has a smaller stake to others where its stake is larger. Management may become entrenched, leaving outside investors incapable of doing anything about these problems. The firms at the top of the pyramid may become too big and politically connected to fail and, knowing that, assume excessive risk.

Nor are financial institutionsimmune fromagency and moral hazard problems. Outside investors will similarly find it difficult to determine whether a bank’s managers are acting in their personal interest or that of the shareholders. Portfolio managers and loan officers will take excessive risks if they expect to be bailed out by the authorities. If management feels pressure from government to lend, it will develop just such an expectation if things go wrong.

Standard logic suggests that the benefits of these extra-market arrangements may dominate their costs in the early stages of economic growth, when there is a need to jump-start industry and market mechanisms are underdeveloped. But with growth and modernization come the development of a better information environment and stronger contract enforcement, at which point it becomes possible to rely more heavily on arms-length transactions. The existence of multiple suppliers of inputs, domestic and foreign, makes hold-up problems less of a concern. And with growth of the domestic market and penetration of foreign markets, adequate demand is assured. At this point the benefits of extra-market arrangements will come to be dominated by the costs.

The problem is that institutional substitutes for missing markets do not slip quietly into the night. Inheritance, or ‘institutional overhang,’ is a problem everywhere. Arguably, however, it has been an especially severe problem in Korea because of the extent to which early growth rested on extra-market mechanisms and because of the telescoped nature of the country’s economic and market development.

It is tempting to characterize Korea as relying mainly on one of these extra market mechanisms, the business groups known as chaebol for example. Other countries could similarly be placed into one of three ‘bins’ according to the mechanism on which they relied. Outcomes in Korea could then be compared with those in other countries making the same choice. Alternatively, outcomes could be compared with those in countries making a different choice. But the reality is that one of these three mechanisms is rarely employed to the exclusion of the others. So it was in Korea, where government, business groups and financial institutions all played a role in coordinating the decisions that shaped the country’s economic development. In terms of understanding the past, the task is to trace their interaction and its consequences. In terms of anticipating the future, it is to imagine how Korea will reform and otherwise deal with a complex institutional inheritance.

1See Eichengreen et al. (forthcoming, chapter 3). 2The historical association of the growth of manufacturing with the growth of the economy as a whole also explains why the falling share of manufacturing in total employment is widely viewed with trepidation. 3Lim&Morck (forthcoming) refer to this as solving the outside investors’ collective action problem. 4Be these social goals or the interest of their political supporters and campaign contributors.

The decision to pursue export-led growth in the 1960s was taken by the government of President Park and ultimately by the president himself. It was implemented in the form of famous monthly meetings of government officials with leading industrialists and attended by the president himself. There was no independent role for the country’s financial institutions, these having been nationalized in 1961. The government exercised firmcontrol over the banks. This meant firm control over the flow of domestic credit, since there did not yet exist securities markets or nonbank financial institutions of any consequence.5 The role of the banks was to provide preferential access to credit at concessional rates to producers who signaled their ability to utilize it productively by meeting their export targets.6

The government’s interlocutors were not yet large business groups but familyowned firms, often trading companies that now moved into the production of light manufactures. Their owner-managers had autonomy in decision making. But they were subject to monitoring by government, something that could have major consequences for access to capital and thereby for a private concern’s broader economic prospects.7

Exports took off in 1964 after the won was devalued and the government imposed an IMF-style stabilization. The response was a 37% increase in exports in 1964 and a further47%rise in 1965.8 Textiles, lumber, plywood, steel and metal products accounted for the majority of those exports. These were mainly laborand resource-intensive goods with substantial imported-input components. And while exports of textiles, lumber, plywood, and steel plate and sheet continued to expand rapidly after 1965, they were increasingly augmented by consumer electronics, electrical machinery, appliances, and transport equipment. Many of these new exports similarly relied on imported parts and components in their early years, not unlike Chinese exports today.

The government might have left it at this. But instead the Ministry of Commerce and Industry moved to establish an ‘Export Situation Room.’ Producers were graded into categories according to whether they met their export targets, and the National Medal of Honor was bestowed on high performers. Exporters were exempted from a domestic commodity and business taxes and cut slack by tax inspectors.

This focus had a number of advantages. Exports were easy to monitor. They provided a simple measure of whether firms were using their preferential access to imported inputs and finance to enhance their competitiveness or whether subsidies were being dissipated as rents. Firms were rewarded with resources for capacity expansion if they performed well by this metric; if not, they were at risk of serious sanctions. That this was a military regime with police powers gave the sanctions teeth. This police power could also be used to monitor the civil service, limiting the scope for rent-seeking and corruption. And relying on export credits for financial allocations meant that there was an objective criterion to limit self-serving discretion on the part of the civil service.

But Korea was still a poor, savings-scarce economy. Mobilizing the capital needed for the expansion of industry and especially the relatively heavy industries that the military aspired to create for national-security reasons required securing capital from abroad. This was another rationale for export orientation: exports were needed to service and repay foreign funds. It was also the rationale for the government’s other principal policy tool: the foreign debt guarantee.9 From 1962, with the passage of the Act for Payment Guarantee for Foreign Loans, the Korean government guaranteed virtually all foreign loans obtained by domestic firms. One can imagine how small firms with little track record of exporting would have found it hard to tap foreign financial markets. Guarantees were almost certainly essential for relaxing this constraint. Access to foreign finance to supplement still-limited domestic finance, whose scarcity was reflected in interest rates that approached 20% even for favored exporters, enabled industrial firms to ramp up more quickly. And borrowing abroad was possible only because the Park regime put the full faith and credit of the government behind these foreign loans.

This interpretation sees government intervention, extending to control of domestic financial institutions, as substituting for missing capital markets. It is consistent with the infant-industry rationale for intervention: Korea’s infant industries had to borrow during their period of learning, after which they could stand on their own.The government intervened close to the underlying distortion, which was the missing capital market, rather than responding with a second-best policy like tariff protection.10 The results turned out even more favorably insofar as at this early stage in the country’s industrial development and in the wake of the corruption scandals of the 1950s policy makers had leverage over business rather than vice versa.

Government guarantees can be problematic. They spawn moral hazard on the part of lenders, who are encouraged to lend irrespective of the capacity of the borrowing firmto repay, and on the part of the borrowers, who take on more debt and pursue riskier projects given the expectation that they will be bailed out if things go wrong. The authorities attempted to limit this last tendency by monitoring the firms whose loans they guaranteed. Firms seeking to borrow abroad had to first obtain the approval of the Economic Planning Board (EPB), which could limit the size of the loan and dictate the uses to which it was put. How the borrower used the funds and his repayment performance were then monitored by the Ministry of Finance (MOF). Inevitably, however, there were slips betwixt cup and lip. Firms increased their indebtedness. They pursued riskier investment projects. But having them do so was precisely the intent of the loan guarantee policy in the sense that the government’s ultimate objective was to accelerate the process of industrialization.

The result was heavier debt burdens and greater financial fragility. Foreign debt service as a share of exports rose from 6% in 1965 to 18% in 1968, 22% in 1969 and 31% in 1970.11 At first positive feedbacks prevailed. So long as capital was flowing in, more borrowing meant more capacity expansion, more exports and, in turn, more foreign borrowing. But as debts mounted and firms moved down the schedule of available investment projects, questions began to be asked. Already in 1969 some 30 firms found themselves unable to meet their foreign obligations. The government, as guarantor of their debts, stepped in and assumed control of their financial operations. As bankruptcies mounted, the authorities took over additional insolvent enterprises. In 1971 they negotiated a program with the International Monetary Fund and, following its advice, devalued, reduced export subsidies, placed temporary ceilings on foreign borrowing, and decontrolled interest rates.

The won was then devalued by 18%, forcing a number of large enterprises with foreign-currency-denominated debts into default and compelling the guaranteeing banks (in reality the government) to bail them out. The authorities gave priority to servicing the country’s external obligations, declaring a moratorium on payments of corporate debt owed to domestic creditors. On 3 August 1972, the president issued an ‘Emergency Decree for Economic Stability and Growth’ declaring an immediate moratorium on the payment of all corporate debt to curb lenders and calling for rescheduling bank loans at reduced interest rates. The moratorium on debt to the curb market lasted three years, at the end of which the debts in question were converted into five-year low-interest loans.12 Thiswas the first crisis inKorea’s modern financial history. Itwould not be the last.

Was this extensive government intervention, in the formof directed lending and foreign loan guarantees, undertaken with the goal of promoting the growth of labor-intensive light-manufacturing industry oriented toward the foreign market, a mistake in light of the crisis in which it culminated? Answering this question requires specifying the counterfactual: how – if at all – Korean industry would have developed in the absence of those policies. One counterfactual is that it still would have developed, just more slowly. The fundamentals for Korea’s successful economic development – a well-educated, hard-working labor force, private enterprises run by ambitious owner-managers, and broadly stable macroeconomic policies – would have remained in place. To be sure, the availability of capital to the private sector would have been less. Investment in manufacturing capacity would have been more limited. There would have been less learning by doing, less learning by exporting, and slower productivity growth. But to say that these things would have happened more slowly is not to say that they would not have happened at all. The Korean economy, in this counterfactual, would have developed in roughly the same fashion, only more slowly.

But another counterfactual is that this development trajectory would not have been sustainable with significantly slower growth. Other countries would have established beachheads in international markets that Korean producers would have been unable to surmount. The slow rise in living standards would have fanned dissatisfaction with the Park Government. Political unrest could have had disruptive and unpredictable consequences for the growth process. Korea paid a price for the government’s policies in the form of heavy indebtedness, excessive risk taking, and financial fragility. But, given how growth proved self-sustaining, it is hard to question that the price was worth paying.

5The Korea Stock Exchange had been created in 1956, but there were few listings of economic consequence. 6Before 1965, when both lending and deposit rates were controlled, access to bank credit meant not just singular opportunities but also significant subsidies; after 1965, although lending rates were allowed to rise, differential access remained. That is, concessional interest rates on export credits remained unchanged (see Hoshi et al., forthcoming). 7As Lim & Morck put it. 8Both measured in dollar terms. 9The other way of attracting foreign finance would have been liberalizing regulations on inward foreign direct investment. But whether Korea would have been an attractive site for the green-field plants of multinational corporations in the 1960s is questionable. In any case, foreign investment remained politically sensitive in the aftermath of Japanese colonialization; hence this alternative was not pursued. FDI accounted for only 4% of the net inflow of foreign capital between 1962 and 1971. 10The latter being the Latin American alternative. 11Krueger (1979, p. 147). 12Lim (2003, pp. 45–6).

The Heavy and Chemical Industry Drive

The 1972 crisis was a wake-up call for the Park Government, which drew two lessons. First, existing mechanisms for allocating credit to anyone with a demonstrated ability to export were inadequately discriminating, EPB and MOF monitoring notwithstanding. What was needed was a more selective approach, where credit was extended to specific firms, in effect to individuals, prepared to commit to the pursuit of priority projects. The second lesson was that expansion of labor-intensive light manufacturing, essentially textiles and electronics assembly operations, had largely run its course. Sustaining industrial development now required moving into more capital- and technology-intensive sectors. This second conclusion dovetailed with the priority that the Park Government had long attached on national security grounds to the development of heavy industry.

Such were the origins of the Heavy and Chemical Industry Drive. Firms were selected for each of the authorities’ priority projects. In return for doing the government’s bidding, they received tax breaks and, importantly given the scale of the newinvestments, favorable access to credit. The authorities, in order to implement their policies, tightened control over the banks and their credit allocation decisions. Interest rates were kept below market levels. With inflation running in the double digits, this made real interest rates sharply negative; in effect, the central bank’s printing press was enlisted in the credit-allocation process. Banks were instructed to direct credit toward targeted sectors, and policy loans were afforded favorable rediscount privileges at the central bank. If anything, this was an even more repressive financial regime than that which had come before. Some 70% of loans flowed to the heavy and chemical industries in the early years of the program.

Other policy loans were extended directly by the state and financed through its budget. Many were underwritten by the National Investment Fund (NIF) established in 1973, which raised resources by selling bonds to captive banks, insurance companies, pension funds, and government agencies. As much as two thirds of the investment portfolio of the NIF was made up of heavy and chemical industry projects. While the NIF did not account for a large share of total bank loans, it provided more than 60% of finance for the heavy and chemical industries’ equipment investment in the second half of the 1970s.

The same firms also enjoyed preferential access to foreign capital: some 80% of foreign loans to the manufacturing sector between 1976 and 1980 were taken up by the heavy and chemical industries. Capital intensity in the country’s light industries actually declined in the early years of the Heavy and Chemical Industry Drive, reflecting difficulties of accessing credit.13 Showered with this abundance of resources, the heavy and chemical industries surged ahead. The period saw the development of a number of successful heavy-industry firms, of which Pohang Iron and Steel Company (POSCO) is emblematic.

This was also, not coincidentally, the period that saw the rise of Korea’s large industrial groups, or chaebol, as family firms favored with preferential access to credit expanded rapidly. The share of the top 10 industrial groups in Korean GDP rose from 5% to 23% between 1973 and 1983.14 The chaebol both augmented their existing businesses and established new ones, and not only in the heavy industries that were the government’s priority. It was not atypical for a chaebol to triple its number of affiliates. Some of these acquisitions could be justified as solving coordination problems – such as avoiding the danger of hold-up by arms-length suppliers in a still relatively thin market. An internationally competitive shipbuilding industry required the production of steel plates tailored to local needs, for example. The return on investment in shipbuilding was affected positively by investment in the steel industry, and vice versa. But not all of this diversification into new activities could be justified on these grounds. Some of it reflected empire building and ego gratification for the individuals at the head of the chaebol.

One view of the symbiosis between the government and business groups is that these two extra-market entities worked together to substitute for missing capital markets and to solve coordination problems.Government and the business groups functioned as a ‘quasi-internal organization’ as described by Lee

Bargaining power was all the more important insofar as the allocation of credit was no longer determined by objective markers such as the rate of growth of exports. It now depended on the personal and political connections of the families undertaking the investments. Officials were confident that they had created a strong bond with the leading industrialists through the export development meetings of the 1960s and that they could rely on these individuals to carry out their wishes. As things turned out, this confidence was not entirely justified.

In an effort to force large firms in the heavy-industrial sector to meet the market test, the government encouraged them to compete for capital by raising it on the market. Between 1973 and 1979 some 300 Korean firms went public. But at this early stage of the country’s security market development, investors had little information about a company’s prospects. In many cases, the founding family hesitated to dilute control; it preferred debt over equity finance. Even where it went ahead with a public offering, the weakness of shareholder rights meant that this only created additional distance between ownership and control, aggravating agency problems.

Given all this, it is not surprising that the outcome of the Heavy and Chemical Industry Drive was mixed. Returns on capital were lower in targeted industries than the economy as a whole, reflecting the difficulty of digesting so much investment. 15 The Blue House’s fixation on scale meant that many plants regularly operated below capacity. The fact that the scale intensity of the heavy and chemical industries favored large firms meant that there was room in the domestic market for only a few. Monopoly rents in turn reduced the pressure for innovation. The result was that it took the targeted firms too long to move down their learning curves. There was less TFP in the heavy and chemical industries than would have been the case otherwise.

Yet, despite these problems, Korea’s high rate of economy-wide growth was maintained. This was all the more impressive given the OPEC oil shocks of 1973 and 1979, Korea’s dependence on imported oil, and the energy intensity of the heavy and chemical sectors.

Again, there are thosewhowould askwhether relying on this uneasy alliance of government and big-business groups as the mechanism for promoting industrial growth had more costs than benefits. It led to an economy dominated by a handful of large industrial groups. These groups had market power. They had political connections that they sought to solidify with campaign contributions and side payments. They were highly leveraged. They were too big to fail. They were not as nimble as the small firms dominating the economic landscape in Taiwan that did not rely on directed credit to the same extent. That the productivity of their investments lagged behind those of other firms in the 1970s suggests that the policies encouraging their growth were pushed too far.

Better in this view would have been for the authorities to have strengthened corporate governance, adopted effective competition policies, and privatized the banks.With more competition and freer entry, hold-up problems could have been avoided.With better developed financial markets, even the most demanding capital requirements could have been met. Coordination problems could have been solved through the emission of price signals.With stronger corporate governance, agency problemswould have been less severe.TheKorean economywouldn’t have come to be dominated by a handful of large, politically powerful conglomerates.

Again, however, this is not the only counterfactual. The capacity to implement an effective competition policy and strengthen corporate governance presupposes administrative capacity. Deep and liquid financial markets together with the rigorous supervision and regulation needed for their effective operation tend to come only late in the economic-development process. Efforts to move in this direction in the 1970s likely would have been premature. The implication is that, in the absence of the government-big-business partnership, growthwould have suffered. Again, this is not to suggest that the country would have never developed more capital- and technology-intensive industry. But movement in that direction would have been slower. And in the long period required for the development of a more capital- and technology-intensive industry, any one of a number of events could have thrown the process off course. Given the rapid expansion of the economy in the face of oil shocks and other obstacles, there is much to say in favor of the path actually chosen.

13Stern et al. (1995, p. 70). 14The share of the top 20 in shipments by the manufacturing sector meanwhile rose from 25% in 1974 to 29% in 1979 and 37% in 1982. Lee et al. (1993, p. 208). 15Stern et al. (1995, p. 78 et seq).

One consequence of the Heavy and Chemical Industry Drive was the accumulation by the chaebol of high levels of debt, especially external debt bearing explicit or implicit government guarantees. The debt/equity ratio in Korean manufacturing rose from an already high 300% in 1974 to nearly 400% in 1980 and 500% in 1982.16 Such high leverage, as would become apparent soon enough, was a source of financial fragility.

Prominent among these debtswere those owed foreign banks.While saving rose with the growth of the Korean economy, investment rose faster. By the early 1970s domestic savings had risen to 15% of GDP (in current prices), but investment rates were 25%. By 1979 saving and investment rates had reached 28 and 35%, respectively. The difference, as in the second half of the 1960s, was funded by foreign borrowing. By 1979, as a result, the external-debt-to-GDP ratio approached 50%, above the levels identified as problematic in the modern literature on debt intolerance.17

The dangers were apparent even to officials heavily invested in prevailing policies. In April 1979 President Park therefore announced a comprehensive stabilization package designed to wind down borrowing for investment in the Heavy and Chemical Industries. At its center were reduced preferences for heavy industry together with initiatives to direct more resources to small firms and light industries. Imports would be liberalized, restrictions on FDI would be relaxed, controlled prices would be freed, and the exchange rate would be allowed to float more freely. This was a major step in the direction of a market footing. These measures were to be backed by macroeconomic stabilization – a reduction in the rate of money and credit growth in particular – to protect against further overheating.

Growth slowed in 1979, as stabilization measures began to bite. The slowdown was then aggravated in October by the assassination of the president, which heightened uncertainty about policy. Growth turned negative in 1980. There then followed a difficult interregnum until General Chun-Doo-Hwan, appointed to investigate Park’s assassination, consolidated his power and was appointed president in 1981. Chun’s government maintained fiscal discipline, pushing the budget further into surplus and freeing up resources for exports. It stepped down the exchange rate and imposed guidelines for wage increases. Supported by exports and competitive labor costs, the economy stabilized and resumed its growth.

Chun and his technocrats, such as his principal economic advisor Kim Jae Ik, firmly believed that Korea needed to continue moving toward a market footing. This meant privatizing the banks and decontrolling interest rates to limit the ability of intervention-minded officials to favor one sector or producer over another. It meant limiting the preferential credit access of the chaebol in order to contain their market and political power. It meant subjecting banks and big business conglomerates to market discipline – allowing them to fail as a result of bad decisions. In short, it meant scaling back the entire constellation of extra-market measures on which the country had relied to drive its industrial growth.

But influential business leaders were prepared to fight tooth and nail for their privileges. Resistance by government bureaucrats was stealthier, but they too had an interest in maintaining their hold on power.18 SMEs and civil society groups were logical allies of the reformers but were not well organized.

Not surprisingly, the record of reform was mixed. A Fair Trade law intended to limit abuses by the chaebol was introduced in 1980.19 But there was no provision for SMEs and other private parties to initiate cases. Everything hinged on the commitment of bureaucrats to the evenhanded application of the law and on the wishful belief that they were immune from chaebol influence.20 More intense import competition would have weakened market power, but the chaebol resisted liberalization. Foreign multinationals were another conceivable source of competition, but the chaebol opposed their entry as well. Nothing meaningful was done to subject controlling interests to discipline from outside shareholders. Where previous excesses and the 1980 recession created a need for corporate restructuring, the authorities engineered mergers and acquisitions, sometimes with the help of public funds, rather than placing distressed chaebol into bankruptcy and possibly damaging confidence and aggravating unemployment.

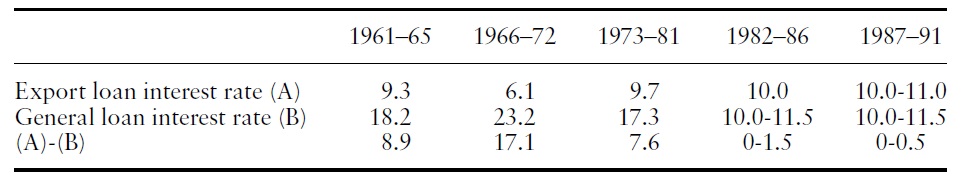

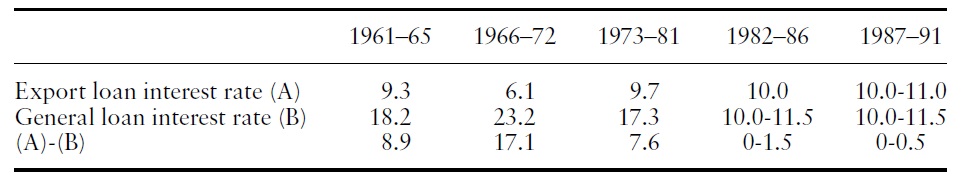

[Table 1.] Interest rate differential between export loans and general loans

Interest rate differential between export loans and general loans

The record of financial reform was similarly mixed. Interest rates on policy loans provided by entities like the Korean Development Bank were brought up to market levels in 1982 (see Table 1). The leading commercial bankswere privatized in 1982–83. However, that the Ministry of Finance retained the right to approve the appointment of bank presidents is indicative of a reluctance to relinquish the government’s long-standing control of the allocation of credit.While officials now may have wished to favor SMEs rather than large enterprises, the problem of inadequate distance between government and finance remained.21 Outside directors on bank boards, for their part, did not have well-defined roles or display the activism necessary to restrain the pursuit by management of personal and political agendas.

Officials had fewer qualms about strengthening the firewalls between the banks and chaebol. When it became evident that the chaebol planned to acquire controlling stakes in the banks in order to retain their preferential credit access, the authorities imposed an 8% ceiling on the share of bank equity that an individual chaebol could purchase. But this did not prevent different chaebol from collectively purchasing larger controlling shares. The chaebol also responded by establishing and purchasing merchant banks, securities companies, investment trusts, and insurance companies.22 Chaebol acquired 19 of the 31 investment finance companies established between the 1980s and early 1990s. Supervision of these nonbank financial institutions (NBFIs) was lax; even basic prudential regulations such as capital adequacy requirements were absent prior to the 1997–98 financial crisis.23

This uneasy tension between inherited extra-market structures and the desire to move the Korean economy to a market footing persisted for the better part of 15 years. Although it was clear that all was not well below the surface, the fact that the economy continued to motor ahead meant that there was no real commitment to do anything about underlying problems. No one wanted to mess with success.

About halfway through the period, starting in 1987, a series of further developments heightened underlying tensions. A first complicating factor was democratization. The transition to democracy in Korea was overdue. It gave voice to homeowners protesting against land grabs by big real estate developers, to retirees, and to other social groups. It provided checks on the arbitrary exercise of concentrated power. But in the short run it mainly weakened existing restraints on the large conglomerates. It curtailed the police power of the state. Competitive elections without checks on campaign finance allowed the chaebol to cultivate political connections that protected them from application of competition policy and gave them confidence that they would receive official aid in the event of difficulties. And when the government sought to push back, chaebol owners made formidable political opponents.24 If there had been an incentive to engage in aggressive capacity expansion and become more leveraged before, that incentive was even greater now.

A second development was further financial liberalization, which afforded the large business groups even freer access to debt finance. The governments of Roh Tae-Woo and Kim Young-Sam sought to move away from the cloistered environment dominated by the chaebol and from the old government-big-business partnership by placing the banks on a commercial footing and more fully opening the market to international competition. Policy lending would become the exclusive domain of the few remaining state banks and be funded via the government budget. No longer enjoying preferential access to credit or monopoly power in product markets, Korea’s large conglomerates, it was hoped, would now focus on profitability rather than empire building. Financial opening also promised reciprocal treatment for Korean firms seeking to set up in other countries. It encouraged joint ventures with foreign firms. It offered more diversified sources of finance for banks and firms seeking to fund investments.

The Roh government committed to fully deregulating financial markets in 1991. In July 1993, Kim Young-Sam then issued a five-year roadmap for accelerated financial liberalization as part of his New Economic Plan to bring financial arrangements into compliance with OECD requirements, Korea now seeking to enter the club of advanced economies. In 1993, the old system in which the government nominated bank presidentswas replaced by one inwhich bank chairmen were selected by committees of shareholders, corporate clients, customers, and former bank presidents.

But supervision and regulation were not upgraded with the same speed that financial markets were liberalized. From 1995, regulators required the banks to adhere to BIS capital adequacy ratios of 8%, to publish up-to-date information on their balance sheets, and to provide detailed information to the authorities along the lines of the Capital adequacy, Asset quality, Management ability, Earnings quality, and Liquidity level (CAMEL) system in the United States. But world-class rules did not mean world-class practice. Supervisors could waive requirements. They required only partial application of provisioning requirements, for example, in order to avoid weakening banks’ earnings reports. Rather than requiring financial institutions to mark to market, they allowed them to value securities at historical cost. Regulators focused on commercial bank exposures while neglecting specialized banks and non-bank intermediaries. The Office of Banking Supervision focused on exposures to the top five and 30 business groups rather than on concentrated exposures generally.25

And a new deposit insurance scheme with a low uniform premium did little to encourage market discipline. Already in 1996 the OECD observed that deposit insurance further weakened the incentive to monitor depository institutions. It warned that disclosure of bad loans was even less complete in Korea than elsewhere. 26 It worried that the scope for management to engage in risk taking was greater than in other OECD countries.

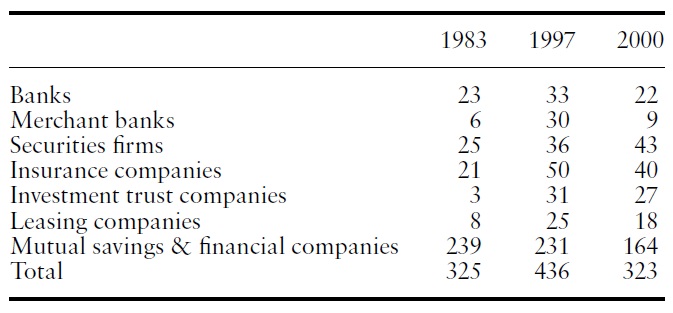

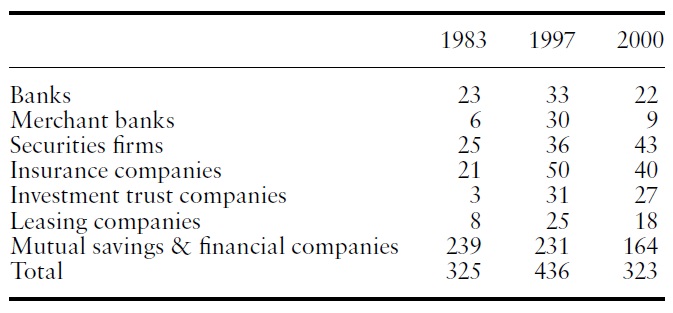

And however bad things were in the commercial banking, in merchant banking they were worse. Merchant banking had been a small backwater until 1994, when entry barriers were reduced as part of the financial liberalization drive. The population of investment banks exploded (Table 2), and many new entrants were chaebol owned. Because merchant banks did not accept deposits, the authorities could maintain that they posed minimal risk to the financial system, justifying light regulation. But in fact the retail products offered by the merchant banks – notably individual investment accounts offering a guaranteed rate of return – were close substitutes for deposits and entailed many of the same liquidity risks. In addition to investing in risky high-yield assets, merchant banks borrowed abroad, short-term in foreign currency, and on-lent to the chaebol, creating currency and maturity mismatches that posed further risks to the financial system, as would become clear in 1997–98.

[Table 2.] Number of financial institutions, 1983?2000 (selected years)

Number of financial institutions, 1983?2000 (selected years)

A third new development was capital account liberalization. Opening the capital account was part and parcel with the efforts of the Roh Tae-Woo and Kim Young-Sam governments to globalize the economy. The policy had been adopted by other advanced economies with market-based financial systems. It was an obligation of membership in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

But the uneven manner in which the capital account was liberalized created vulnerabilities. The only nonfinancial entities permitted to tap foreign capital markets were companies investing in infrastructure projects, subsidiaries of foreign companies in technology-related industries, companies pre-paying existing foreign debts, and SMEs (which were unlikely to be able to access those markets in any case). Other companies, notably chaebol, could obtain foreign credits only by applying to domestic financial institutions. Thus, if capital inflows turned around, the resultwould be more than just corporate finance distress and isolated bankruptcies. It would be a systemic liquidity crisis attacking the lifeblood of the financial system.

Then there was the fact that starting in 1994 the authorities lifted ceilings on short-term foreign currency borrowing by commercial banks while leaving the ceiling on medium and long-term borrowing in place. Short-term borrowing, it was believed,would be mostly trade-related financing thatwould be rolled over so long as exports continued to grow. Short-termforeign liabilities did not add to the stock of effective foreign obligations since they were repaid once the underlying export and import transactions were completed, typically within a year.27 The reality, of course, was different. If the flow of foreign equity investment slowed or, worse, reversed, equity prices could simply decline. If foreign finance was longterm– if it flowed into bonds – bond priceswould simply fall. If it took the formof inward FDI, its slowingwould not jeopardize the financial system. The reversal of short-term capital flows intermediated by the banks, in contrast, could threaten financial stability.

And no one had better access to cheap foreign finance than the chaebol, which could access it via merchant as well as commercial banks. The debt/equity ratio of the top 30 chaebol reached an astonishing 518% in 1997.28 Confident that they were too big to fail, the chaebol used foreign finance to both expand capacity in their existing business lines and branch into additional activities. That their funding was mainly debt intermediated by the banks, which borrowed abroad and on-lent to domestic business, had the further advantage that it did nothing to dilute the control of corporate insiders. Indeed, capital account liberalization had the unintended consequence of widening further the gap between ownership and control and aggravating moral hazard problems. The government’s efforts to encourage the chaebol to go public worked in the same direction. There were still few independent directors to advocate for outside shareholders. Controlling shareholders could still select directors. It was hard for outsiders to reliably determine what was going on, given auditing and accounting practices that did not approach international standards. Investors with less than5%of shares could not remove a director, demand a shareholder’s meeting, or scrutinize a company’s books. Poor share price performance did not translate into market discipline, given the prevalence of cross-ownership and pyramiding.29

These problems had consequences. Except in 1994–95, a boom period for electronics, chaebol performance continued to disappoint. Operating income as a share of sales was persistently below that of independent firms. The return on assets in manufacturing for the top 30 chaebol was just 0.7% in 1996, below the cost of capital, which bode ill for financial stability.30 It trended downward as the period progressed, indicating that problems were mounting. These disappointing returns reflected aggressive expansion. They reflected excessive diversification. Indeed, despite the authorities’ best efforts, the number of industrial branches of the top chaebol continued to rise. The result was neglect of core competency. It was an inability of the head office to control far-flung operations. All of this was common knowledge among investors: equity claims on the chaebol, which had traded at a premium relative to claims on other companies in the 1980s, now traded at a discount.31

Seen in this light, the 1997–98 crisis reflected more than just panic on the part of foreign investors who abruptly refused to roll over their loans to Korean banks. To be sure, the crisis was fed by events beyond orea’s control. It occurred against the backdrop ofThailand’s sudden devaluation and then contagious crises of confidence affecting Indonesia, Hong Kong and other East Asian economies. When the vulnerability of other emerging Asian economies was visibly revealed, there was no particular reason to think that South Korea would remain immune. There was the tightening of US monetary policy. There was the slowdown in the global electronics industry. There was the rise of Chinese competition. But to attribute Korea’s crisis to these foreign factors and to panicky foreign investors is to overlook domestic factors. In some sense the crisis was only the culmination of ongoing problems of uneven financial liberalization and weak corporate governance inherited from the earlier era of government-business symbiosis.

16See Hoshi et al. (forthcoming). 17For example Reinhart et al. (2003). 18They also had to spend much of the 1980s undoing the legacy of problems created by overly ambitious HCI firms. 19It had actually been passed by the Congress in 1976 but was not activated at that time. 20And until 1994 the Korea Fair Trade Commission (KFTC) remained under the authority of the Economic Planning Board, as a result of which competition policy was subordinated to other economic policy goals. Whenever a large firm insisted that a merger or acquisition was essential for the maintenance of competitiveness, the KFTC disregarded the implications for market power, rejecting only three of the nearly 2000 merger proposals it examined in the 1980s. 21In 1980 the authorities mandated that 55% of the increase in local bank credit and 35% of city banks’ credit should go to SMEs. In 1984, it temporarily froze bank credits for the top 5 chaebol and set credit ceilings for the top 30. The Office of Bank Supervision was given authority to limit the share of loans to individual chaebol in individual banks’ asset portfolios. 22The decision in the early 1980s to relax entry barriers affecting non-bank financial institutions can be understood as a response by the government to the danger that commercial banks with MOF-approved presidents might still fail to make lending decisions on a purely commercial basis; competition from NBFIs was a limited way of subjecting them to market discipline. The critical mistake was to assume that NBFIs would be motivated to allocate resources in a manner consistent with market efficiency and not simply cater to the needs of the chaebol. 23For more on this, see below. 24In 1991, Hyundai chairman Chung Ju-Yung launched the Unification National Party with the aim of running in the National Assembly elections of 1992.That the government also slapped a $180 million fine on Hyundai for illegal stock transactions had more than a little to do with Chung’s political activism. In April 1992, coincident with the campaign for the National Assembly, the government arrested more than a dozen Hyundai executives on charges of tax evasion. Chung launched a public counterattack. The eventual truce involved having the anti-chaebol officials leaving the Economic Planning Board and the Blue House, and Hyundai paying taxes and fines. 25All of these problems became evident well before the crisis of 1997–98, as noted in, inter alia, OECD (1996). 26OECD (1996, pp. 78–79). 27See the discussion in Hoshi et al. (forthcoming). 28Chopra et al. (2001, p. 21). 29Which prevented hostile takeovers. 30See Krueger & Yoo (2002) and Haggard et al. (2003). 31Lim & Morck (forthcoming, pp. 309–311).

Conclusion: Post-crisis Reform and the Unfinished Agenda

The crisis was a clarion call that earlier efforts to place the economy on a market footing had been inadequate. The depth of the recession, with the economy shrinking by 7% in 1998, pointed up the urgency of acting. The embarrassment of having to request IMF assistance, a step to which no OECD country had been driven for 20 years, empowered reformers who could now argue that painful medicine was justified to prevent this from ever becoming necessary again. The damage done to the banks and the chaebol and their nowall-but-complete dependence on the government limited the ability of vested interests to push back, at least temporarily.

The first wave of post-crisis reforms was shaped by the urgent need to stabilize the financial sector and restructure corporate finances and operations. Prudential supervisionwas consolidated in the newly created Financial Supervisory Commission (FSC). The banking system was consolidated around a core of strong banks, a transition engineered using merger, the closure of weak banks, and asset sales. The FSC formulated a rehabilitation or resolution strategy for each institution. The strategy was then executed by the Korea Asset Management Corporation (KAMCO), which purchased impaired assets, and by the Korea Deposit Insurance Corporation (KDIC), which injected capital and reimbursed depositors.32 By early 2000 the number of commercial banks had fallen from 26 to 7. Since the merchant banks were small, they could be closed without worsening the credit crunch or aggravating the recession. This strict approachwas also consistent with the government’s desire to rein in the chaebol and reduce debt-equity ratios, since the merchant banks had been used to funnel savings into bonds issued by the chaebol and had extended unsecured loans. Ten merchant banks were closed in January 1998; four more were closed in April 1999, and another was closed in June. Two remaining merchant banks were then absorbed by commercial bank partners. An industry that had entered the crisis with 28 incumbents emerged with only 11. This was an extraordinary change for a country that had never experienced the closure of a major financial institution.

In May 1998 all industries except those related to national security and environment were thrown open to foreign competition. This included the financial sector. Foreign investors were allowed to acquire Korean financial institutions. Foreign owners brought with them their business plans and practices. They trimmed staff and branches. They strengthened internal systems. They demanded representation on the boards of the institutions in which they were invested.

Earlier problems created by partial and uneven opening of the capital account were now addressed. Firms were permitted to borrow abroad at long as well as short tenors. The red tape to which foreign direct investment in Korea was subject was simplified, with the goal of now attracting rather than repelling FDI.

Corporate restructuring, while more limited, was nonetheless extensive. By the end of 1999, 14 of the 30 largest chaebol had entered bankruptcy or workout programs. Some survivors, such as Samsung, still remained in the hands of the descendants of the founding family, but not others. Large corporations desperate for cash sold off important subsidiaries, such as Samsung Motor and Hyundai Construction.

The decision in August 1999 to allow Daewoo, the second largest chaebol, to declare bankruptcy was meant to signal the death knell of ‘too big to fail.’ But the action had unintended consequences. Daewoo had 85 trillion won of debt, the equivalent of 15% of Korean GDP. Allowing this now to lapse into default threatened to destabilize the investment trust companies, which held the vast majority of Daewoo’s speculative securities. The ITCs were forced to liquidate assets, including the bonds and commercial paper of other big corporations. This was a blow to other firms already in a weakened financial state. The government was forced to organize a 20 trillion won capital-market stabilization fund to bail out medium-sized chaebol with commercial paper coming due. This experience was a harbinger of how it would be more difficult than expected for government to distance itself from the corporate and financial sectors.

While some top chaebol were devastated, others seized the opportunity afforded by the failure of their competitors. They resisted downsizing. They resisted becoming more transparent. They resisted efforts to open their sheltered markets to foreign competition. The large chaebol were still able to access external finance by issuing bonds, some of which were purchased by their still captive investment-trust insurance companies. They used the resources to scoop up distressed companies and restructure their operations.

The government sought to force the conglomerates to focus on their core competencies by engineering a series of so-called ‘Big Deals.’ They encouraged Hyundai Electronics to acquire LG Semiconductor and, in the refinery industry, Hyundai to take over Hanwha. Korea Heavy Industries was encouraged to take over the power generation facilities of Hyundai Heavy Industries and Samsung Heavy Industries. But simply encouraging a firm to concentrate on a specific industry did not guarantee technological progressiveness or prevent investment in excess capacity. In a sense, the approach was just another legacy of the authorities’ long-standing preference for scale and top-down planning. The Big Deal approach had many of the same problems as the Heavy and Chemical Industry Drive, with the government proposing which affiliates should merge and which chaebol should sell or acquire specific units.33 It is revealing that many Big Deals were never completed. While Samsung, Hyundai and Lotte took steps to reduce the cross-industry dispersion of their business activities, there was little evidence of this in groups such as LG and SK. In fact, there was a rebound in the extent of diversification and the number of affiliated companies starting in 2000–2001.

The most fundamental of these reforms, those affecting corporate governance, similarly remained incomplete. Corporate governance reformhad been part of the agreement with the IMF, and the political outsider Kim Dae-Jung, elected president in thewake of the crisis, sawit as a route to a more transparent and equitable society. Because Korea had relatively well-developed financial markets, the government opted for the Anglo-Saxon approach in which shareholders, concerned to see the value of their investments maximized, are the source of discipline on insiders. Some observers questioned whether the Anglo-Saxon model was suited to the circumstances of a country dominated by industrial groupswhose existence makes information on individual firms hard to obtain. In such an economy, the argument goes, monitoring of corporate insiders is better undertaken by banks. Be that as it may, the government was now committed to reducing the role of the banks in the economy.

Efforts thus focused on strengthening the role of directors with the goal of empowering outside shareholders. Directors were given a fiduciary responsibility. Those appointed by controlling shareholders were subjected to the same legal obligations as elected directors. Starting in 1998, all listed companies were required to appoint at least one outside director. In the case of listed companies, outside directors had to account for at least a quarter of the board. In 2001, this requirement was raised to at least a half of directors in the case of corporations with total assets of over 2 trillion won. As Hoshi, Kim and Park note, by the end of 2006 some 1200 outside directors had been appointed by 725 listed companies.

To protect minority shareholders, the voting shares needed to initiate the removal of a director, file a derivative suit, and inspect the corporate accounts were all lowered. June 1999 saw the introduction of a cumulative voting system, which was introduced to enable minority shareholders to elect a director to represent their interests. This permitted shareholders with less than 3% of outstanding stock to appoint a director, placing an additional check on the temptation of controlling interests to exploit minority shareholders. However, this system was not mandatory and most of the listed firms affiliated with chaebol simply amended their charters to prevent cumulative voting.

More generally, the presence of outside directors does not ensure the representation of minority investors when those filling the seats were associated with the company or controlling family previously, as was not infrequently the case. Similarly, simply mandating the publication of accurate financial statements does not make it happen. There remain significant gaps between the principle and practice.

Having said all this, there was significant progress in strengthening corporate governance in the first post-crisis decade. Reflecting pressure to deliver shareholder value, Choe & Roehl (2005) find a tendency for chaebol groups to consolidate their smaller affiliates into larger, more efficient entities. They find that chaebol groups were most inclined to divest themselves of loosely coupled units outside their core competencies. They conclude that most business groups that survived the crisis transformed themselves into more focused organizations. Empirical studies find a clear acceleration of productivity growth in the manufacturing sector after the turn of the century.34 This acceleration was most pronounced in chaebol-dominated sectors: industries producing motor vehicles, chemicals, telecommunications equipment, and miscellaneous electronics.

Be this as it may, the task of updating institutional arrangements to better serve the needs of an advanced economy remains incomplete. Korea still faces the challenge of dealing with the legacies of its earlier government intervention, large business groups, and idiosyncratic financial development. Realistically, the solution is not to ‘get the government out of the economy’ or to ‘break up the chaebol.’ Inherited structures are not going away. The challenge, rather, is to reform and update them so that they are better positioned to help the country meet the challenges of the twenty-first century.

32KAMCO bonds were given to banks in exchange for NPLs. KAMCO financed its operations by issuing its own bonds, guaranteed by the government, and by borrowing from the Korean Development Bank. KAMCO was to purchase nonperforming assets at their fair market value. KAMCO presented the price on a take-it-or-leave-it basis, given that there were few other buyers in the event that a financial institution resisted the terms. 33Revealingly, the main industries subject to these deals (petrochemicals, oil refining, motor vehicles, other transport equipment) were the same ones that had once been the subject of the Heavy and Chemical Industry program.