The European Union (EU) was established by the Treaty of Rome, signed in 1957 by West Germany, France, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. The number of EU member countries increased to 15 after the United Kingdom, Denmark and Ireland joined in 1973, Greece in 1981, Spain and Portugal in 1986, and Austria, Finland and Sweden in 1995. Membership increased to 27 mostly after the former communist countries in Central and Eastern Europe became members of the EU. Poland, Hungary, Czech Republic, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia, Malta and Cyprus joined in 2004, and Bulgaria and Romania in 2008. With 12 new member countries joining since 2004, the EU has a population of nearly 500 million, and the EU’s GDP is bigger than that of the USA. Now, the EU is the world’s leading exporter and importer of goods and commercial services.

At the basis of the EU’s leading role lies the EU’s common commercial policy (CCP). EU member countries transferred their competences in this policy area to the supranational level to speak in unison on trade. The EU adopted he Global Europe Strategy in 2006 to ensure the EU’s competitiveness in the world by removing barriers to trade and to sharpen the contribution of trade policy to growth and jobs in Europe. The Free Trade Agreement (FTA) between the EU and the Republic of Korea (EU-Korea FTA) is the first of the new generation of FTAs as part of the Global Europe Strategy.

This paper examines the EU’s CCP and suggests its implications for the Korea-EU relationship. The structure of this paper is as follows. Section 2 presents the position and patterns of EU trade in regards to world trade. Section 3 reviews the EU’s CCP and Global Europe Strategy. Next, we look at the EU-Korea FTA and its implications for the Korea-EU relationship in Section 4. Section 5 concludes.

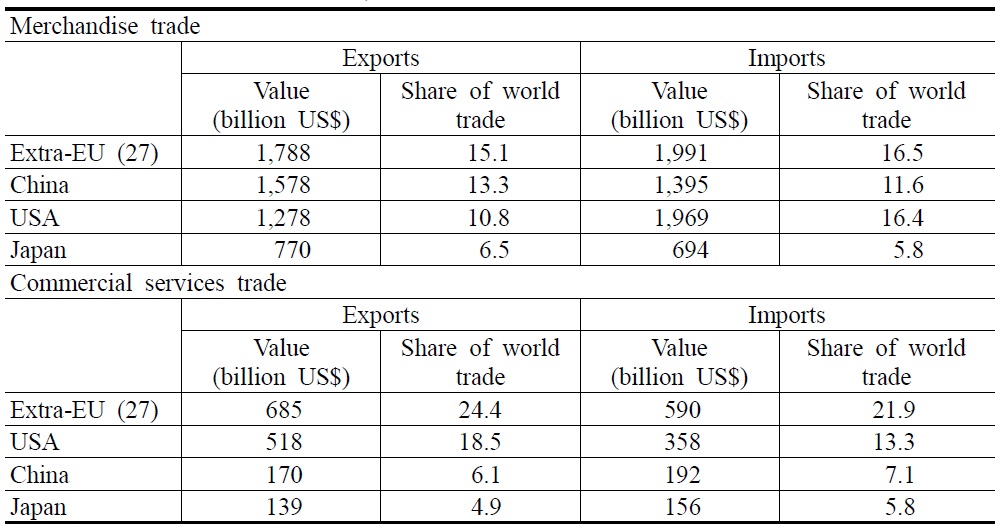

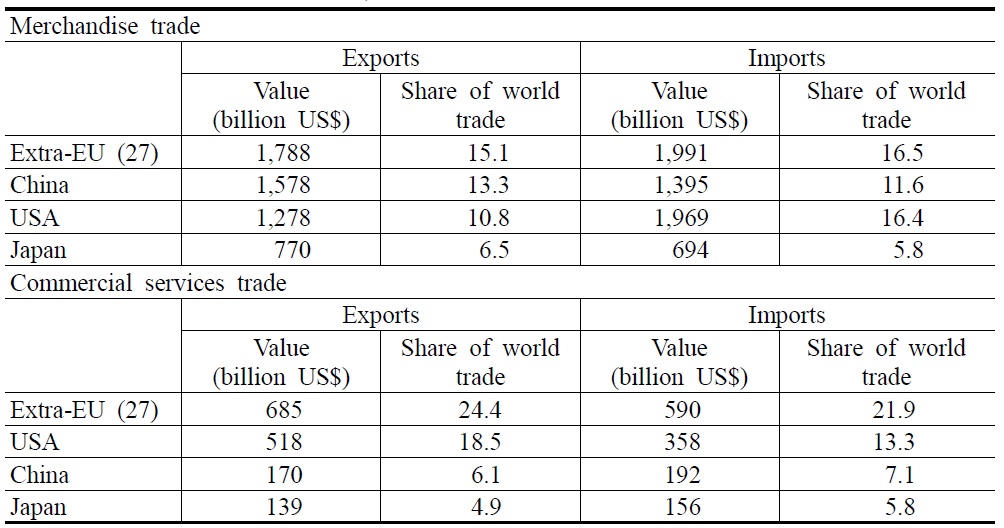

The EU is the world’s leading exporter and importer of goods and commercial services. As we can see in Table 1, in 2010, the EU accounted for 15.1 percent of world exports and 16.5 percent of world imports in goods. The shares of EU external trade in world trade are even higher for trade in commercial services, with the EU-27 representing 24.4 percent of world exports and 21.9 percent of world imports (WTO, 2011).

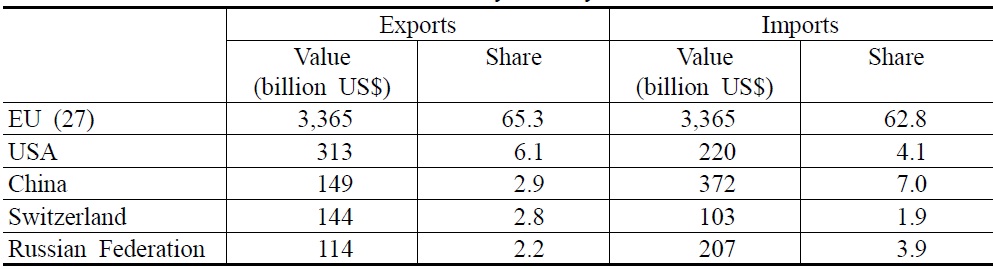

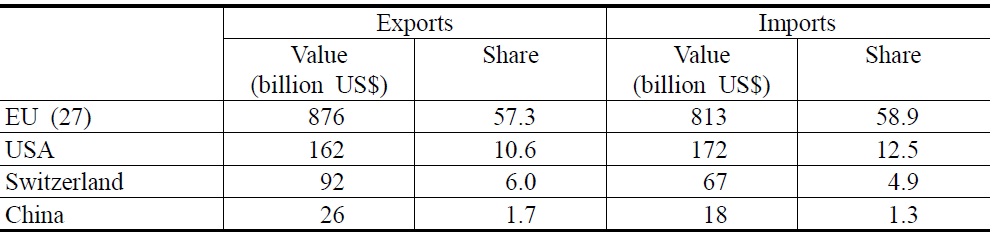

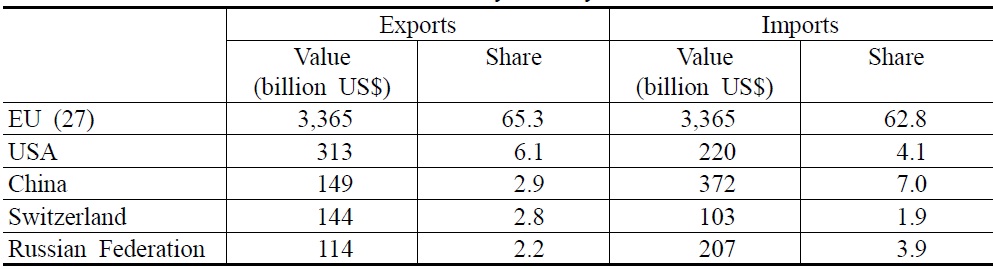

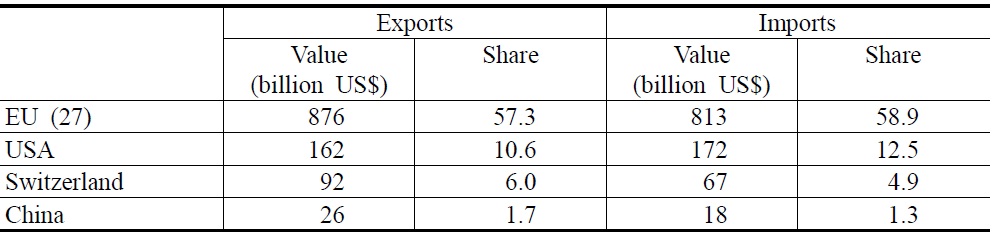

The trade shares shown in Table 1 do not include intra-EU trade. Intra-EU trade has increased in recent years as the trade with the acceding countries has become internal. If we take into account trade among the member countries, in 2010, the EU accounted for 37.9 percent of world merchandise exports and 38.9 percent of world merchandise imports. We can confirm the importance of intra-EU trade from Table 2, which shows the main EU trading partners. The vast majority of the merchandise trade of the EU occurs between member countries and outside the EU, where the major trading partners are the USA, China, Switzerland and the Russian Federation. Similarly, the overwhelming majority of the commercial services trade of the EU occurs between member countries, and outside the EU, where the main trading partners are the USA, Switzerland and China (see Table 3).

Leading Exporters and Importers in World Trade in Merchandise and Commercial Services, 2010

[Table 2] Merchandise Trade of the EU by County, 2010

Merchandise Trade of the EU by County, 2010

[Table 3] Commercial Services Trade of the EU by County, 2009

Commercial Services Trade of the EU by County, 2009

In terms of trade composition, the vast majority of EU merchandise trade occurs in manufactured goods, while trade in services consists mainly of trade in travel and transportation. It should be pointed out that even though EU trade with non-EU countries accounts for the largest share of commercial services trade in the world in 2010, its share has decreased over the years. Looking at the relationship between the EU and its trading partners, the commodity structure of EU trade seems to vary across trading partners. It can be found that manufactured goods figure more clearly in EU trade with other developed countries, while EU merchandise trade with developing countries is dominated by primary products (WTO, 2011).

The EU has used this commercial superiority as a diplomatic method. Sapir (1998) argues that trade policy has been the principal instrument of foreign policy for the EU. To increase the EU’s geopolitical interests, access to the EU market, financial aid, economic cooperation and infrastructural links have been utilised. Especially to the EU’s immediately neighbouring countries, a privileged trade relationship in the form of association or cooperation agreements has been offered in exchange for their commitments to some values such as respect for the rule of law, good governance and respect of human rights with the goal of extending stability, security and economic development (Conconi, 2009).

Ⅲ. The EU’s Common Commercial Policy

Since the Treaty of Rome in 1957, EU member countries began to speak in unison on trade, transferring their sovereignty in the trade policy area to the supranational level. A customs union was created among the six original EU member countries in 1968. The important measures of a customs union included: the elimination of all customs duties and restrictions among EU member countries; the introduction of a Common External Tariff to replace national tariffs vis-a-vis non-member countries; and the establishment of the CCP as an external dimension of the customs union. EU integration has advanced beyond the common market to the stage of the European Economic and Monetary Union (Conconi, 2009; Horng, 2012).

EU integration has evidently led to economic benefit. The internal markets of the EU have brought free trade, free movement of production factors, more efficient resource allocation, structural adjustment, job creation, economies of scale, increase in productivity, fairer competition, price transparency, and wider consumer choice. Along with these trade creation effects, the internal markets contributed to the development of world trade, the improvement of terms of trade, and the bargaining power of the EU through the CCP (Emerson et al, 1988; Zervoyianni, 2006).

In terms of the decision-making process, the European Commission has been in charge of the implementation of the CCP, proposing new trade initiatives to the Council, managing trade tariffs, and conducting trade negotiations. At the conclusion of negotiations, the Council approved or rejected the trade agreement before the Lisbon Treaty. With the exception of sensitive areas, trade policy decisions by the Council have been made by qualified majority voting. EU member countries are assigned different voting weights, which vary according to the population size, and ratification requires approval by two-thirds of the votes. The Treaty of Rome provided no role in trade policy for the European Parliament. Since then, the European Parliament has played a limited role (Conconi, 2009).

Under primary legislation such as treaties and other agreements of similar status, the EU concludes and implements the CCP. The CCP includes all sides of trade in goods, services, intellectual property, and foreign direct investment (FDI) as extended under the Lisbon Treaty, which became effective in December 2009. Under the Lisbon Treaty, the Treaty of European Community was renamed as the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). The key provisions of the CCP are contained in Articles 206-7 TFEU. Under the Lisbon Treaty, the workings of the EU have been streamlined for the purpose of enhancing its efficiency and democratic legitimacy and improving the coherence of its actions. The Lisbon Treaty includes more efficient decision-making processes, a greater role for the European Parliament, and more coherence in the EU’s external actions. Especially, the Lisbon Treaty gives the European Parliament the same degree of legislative power as that exercised by the Council of the EU and requires the European Parliament’s assent for all related international agreements. Therefore the European Parliament can bring a broad range of voices and opinions to the debates on trade, and thus transparency and legitimacy in the EU CCP will be increased through these changes (Conconi, 2009; Horng, 2012).

The Lisbon Treaty extends the scope of the CCP by including trade in services and FDI and simplifies the provision of uniform protection for intellectual property rights (IPRs). The Lisbon Treaty has exclusive competence on FDI as part of the CCP. The EU tries to obtain access for investment in its trading partners’ markets. For European investors to be served equally and effectively, liberalisation and investment protection standards are integrated into the CCP. Thus, investment protection is expected to be an important issue in future EU FTA agreements (Horng, 2012; Piris, 2010).

Even though the negotiation and conclusion of a trade agreement or FTA requires a qualified majority vote in most cases, the negotiation and conclusion of agreements in the fields of trade in services and the commercial aspects of intellectual property, FDI, trade in cultural and audiovisual services, and trade in social, education, and health services all need unanimity. For negotiating FTAs, the Commission requests authorisation from the Council and negotiates with the trading partner on behalf of the EU and coordinates with the EU member countries and the European Parliament. For the approval of the outcome of an FTA, a qualified majority vote by the Council and consent by the European Parliament are needed. The EU may include dispute settlement procedures and provisions to address possible future problems at the highest political level within its FTA (Craig, 2009; Horng, 2012).

To set out the contribution of trade policy to stimulating growth and creating jobs in the EU, the EU adopted the Global Europe Strategy in 2006. The Global Europe Strategy sets out how, in a rapidly changing global economy, to build a more comprehensive, integrated, and forward-looking external trade policy that makes a stronger contribution to the EU’s competitiveness. It also emphasises the need to adapt the tools of the EU trade policy to new challenges, to engage new partners, and to ensure the EU remains open to the world and other markets open to the EU. Reducing tariffs still remain important to opening markets to EU’s industrial and agricultural exports. But as tariffs fall, non-tariff barriers (NTBs) become the main obstacles. NTBs are more complicated and more sensitive because they touch directly on domestic regulation. To promote trade and prevent distorting rules and standards, instruments such as mutual recognition agreements, international standardisation and regulatory dialogue as well as technical assistance to third countries will be needed (European Commission, 2006).

EU will focus on market opening and stronger rules in new trade areas of economic importance such as IPRs, services, competition, investment, and public procurement. The Commission has used considerable resources to fight counterfeiting and improve IPR enforcement in key third countries such asChina. The EU will also negotiate to liberalise trade in services with key trading partners, especially where market access is poor or EU partners have made few World Trade Organisation (WTO) commitments. The absence of competition and state aid rules in third countries will restrict market access as it raises new barriers to substitute for tariffs or traditional NTBs. The EU has developed international rules and cooperation on competition policies to ensure EU firms do not suffer in third countries from unreasonable subsidisation of local companies or anti-competitive practices (European Commission, 2006).

Improving investment conditions in third countries for services and other sectors will contribute to economic growth in the EU. As supply chains are globalised, for EU companies to invest freely in third countries will be more important in order to realise business opportunities, make the flow of trade more predictable, and consolidate the image and reputation of the firm and of the country of origin. Public procurement is an area of undeveloped potential for EU exporters. Even though EU companies are excellent in areas such as transport equipment, public works and utilities, they face discriminatory practices in EU trading partners, which effectively close off exporting opportunities. Public procurement may be the biggest trade sector remaining sheltered from multilateral disciplines (European Commission, 2006).

The EU remains committed to the WTO and works to resume negotiations as soon as possible. FTAs, if approached with care, may build on the WTO and other international rules by promoting openness and integration, by tackling issues which are not ready for multilateral discussion and by preparing the ground for the next level of multilateral liberalisation. On the other hand, FTAs can carry risks for the multilateral trading system because they may complicate trade, erode the principle of non-discrimination and exclude the weakest countries. Therefore, to ensure that any new FTAs serve as a stepping stone and not a stumbling block for multilateral liberalisation, they need to be comprehensive in scope, provide for liberalisation of most trade and go beyond WTO disciplines. FTAs are by no means new for the EU. FTAs are part of EU negotiations for Economic Partnership Agreements with the African, Caribbean and Pacific countries and of future association agreements with Central America and the Andean Community. But while FTAs play an important role in the European neighbourhood by reinforcing economic and regulatory ties with the EU, the EU’s main trade interests, including in Asia, are less well served (European Commission, 2006).

The key economic criteria for new EU FTA partners will be market potential (economic size and growth) and the level of protection against EU export interests (tariffs and NTBs). The EU also takes account of potential partners’ negotiations with EU competitors, the impact on the EU, and the risk that the preferential access to EU markets currently enjoyed by EU neighbouring and developing countries may be eroded. Based on these criteria, ASEAN, Korea and MERCOSUR (Southern Common Market) which includes Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay, emerge as priorities. These countries unite high levels of protection with large market potential and are active in concluding FTAs with EU competitors. India, Russia and the Gulf Cooperation Council which includes Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates also have combinations of market potential and levels of protection which make them of direct interest to the EU. China also satisfies many of these criteria, but requires special attention because of the opportunities and risks it presents. New FTAs tackle NTBs through regulatory convergence and contain strong trade facilitation provisions. New FTAs include stronger provisions for IPR and competition. The EU tries to include provisions on good governance in financial, tax, and judicial areas where appropriate. The EU ensures that the Rules of Origin in FTAs are simpler and more modern and reflect the realities of globalisation. The EU will strengthen sustainable development through bilateral trade relations in considering new FTAs. This could include incorporating provisions in areas relating to labour standards and environmental protection (European Commission, 2006).

The Europe 2020 Strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, which the EU suggested in 2010 as the trade strategy for Europe leading up to 2020, includes:

Ⅳ. Implications for Korea-EU Relation

The EU and Korea are important trading partners. In 2011, Korea was the EU’s sixth largest trading partner outside Europe (behind USA, China, Japan, India and Brazil) and tenth overall. The EU is among Korea’s top four largest export destinations following China, Japan, and the USA. EU exports to Korea have recorded an annual average growth rate of 7 percent between 2007 and 2011. However, because of the financial crisis, this trend slowed down in 2009. In 2009, the EU’s exports to Korea reached EUR 21.5 billion and Korea exported EUR 32.2 billion worth of goods to the EU. In 2010, the trade flows increased. The EU exported to Korea EUR 28 billion worth of goods, whereas Korea exported to the EU EUR 39.2 billion. In 2011, EU good exports to Korea reached EUR 32.4 billion and Korean good exports to the EU reached EUR 36.1 billion. It should be pointed out that the value of the Korean trade surplus vis-a-vis the EU in 2011 decreased to EUR 3.6 billion from EUR 11.3 billion in 2010. The main Korean exports to the EU in 2011 were machinery and transport equipment (64.1%), manufactured goods classified chiefly by material (12.3%), and miscellaneous manufactured articles (9.6%), whereas the main EU exports to Korea were machinery and transport equipment (49.8%), chemicals and related products (16.4%), manufactured goods classified chiefly by material (10.5%), and miscellaneous manufactured articles (10.2%). In 2010, the value of Korean services exports to the EU reached EUR 4.5 billion, while Korea absorbed EUR 7.5 billion of EU services. European companies are consistently the largest investors in Korea, representing a cumulative total of about EUR 30 billion since 1962 (European Commission, 2012).

The FTA between the EU and Korea, for which the negotiation was embarked in May 2007 and finalised after eight formal rounds, was initialled on 15 October 2009. The EU-Korea FTA is the first one where the European Parliament has endorsed a trade agreement and adopted the accompanying trade legislation under the Lisbon Treaty. The Safeguard Regulation, which is accompanied with the EU-Korea FTA, is the first major ordinary legislative procedure on trade where the European Parliament was involved. According to the safeguard measures, it is possible for the EU to suspend further reductions in customs duties or increase them to previous levels if the lowest rates give rise to an excessive increase in imports from Korea, causing or threatening to cause serious injury to EU producers, particularly in the EU automotive industry (European Parliament, 2011; KITA, 2010).

The EU-Korea FTA is also the first of the new generation FTAs as part of the Global Europe Strategy. The EU-Korea FTA is the most comprehensive free trade agreement ever negotiated by the EU. Import duties are removed on nearly all products and there is grand liberalisation of trade in services. It contains provisions on investments both in services and industrial sectors, and strong disciplines in important areas such as the protection of intellectual property (including geographical indications (GIs)), public procurement, competition rules, transparency of regulation and sustainable development. Specific commitments to eliminate and to prevent NTBs to trade have been agreed on sectors such as automobiles, pharmaceuticals or electronics. Both parties have agreed to the commitment to promote cultural diversity in accordance with the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) Convention in a Protocol on Cultural Cooperation (European Commission, 2010b).

The EU-Korea FTA comprises of fifteen chapters, several annexes and appendixes, three protocols and four understandings. According to chapter 2, customs duties are removed over a transitional period so that domestic producers can gradually adapt to the lowering of customs duties. The majority of customs duties on goods will be removed at the entry into force of the agreement. Practically all customs duties on industrial goods will be removed within the first 5 years from the entry into force of the FTA. In the case of both industrial and agricultural products, Korea and the EU will remove 98.7 percent of duties in trade value within five years from the entry into force of the FTA. The EU-Korea FTA will swiftly remove EUR 1.6 billion of customs duties which EU exporters to Korea face every year. Clearly, potential gains will be even higher as the trade between Korea and the EU expands due to the FTA. Machinery and appliances sector will be the largest beneficiary where duties are saved with gains close to EUR 450 million. The chemical sector is the second largest sector where EUR 175 million worth of duties will be relived. The most sensitive industrial products including passenger cars with small sized engines, consumer electronics such as TV sets, video recorders and LCD monitors have a five year liberalisation period, and a number of other sensitive goods, including cars with large or medium engines, have a three year liberalisation period. The EU-Korea FTA will liberalise EU agricultural exports to Korea (e.g., wine is duty-free from day one, whiskey on year 3 and there will be valuable duty-free quotas for products like cheese from the entry into force of the agreement). Certain EU pork exports will have duty free access from year 5. However, for a limited number of highly sensitive agricultural and fisheries products such as frozen pork belly, transitional periods longer than seven years have been given. Rice and a few other agricultural products are excluded from the agreement. European agricultural exporters will save EUR 380 million annually on duties for agricultural products, for which Korean duties are very high (35 percent by weighted average). Considering very high Korean tariffs, the potential for expanding EU exports is considerable (European Commission, 2010b).

The EU-Korea FTA includes fundamental WTO rules on NTBs to trade, such as national treatment, prohibition of import and export restriction, disciplines on state trading etc. The EU-Korea FTA is the first FTA to include specific sectoral disciplines on NTBs to trade. Export duties are prohibited from the entry into force of the agreement. Specific NTBs such as differing standards relating to automotive, electronics, pharmaceuticals and chemicals are dealt with in separate annexes to the agreement. In view of their detailed and technical characteristic, these NTBs are difficult to address and require entering deeply into the regulatory practices of trading partners. Because many NTBs are a side effect of the otherwise legitimate pursuit of public policy objectives, surmounting the negative side effects requires finding carefully balanced solutions. The EU-Korea FTA sets up a Committee on Trade in Goods that shall meet at the request of either party. This committee will consider broadening the scope of NTB disciplines and promoting liberalisation as well as tackling other issues related to trade in goods between Korea and the EU (European Commission, 2010b).

The EU-Korea FTA is by far the most ambitious services FTA ever concluded by the EU. The scope of the EU-Korea FTA includes diverse services sectors such as transportation, telecommunications, finance, legal services, environmental services and construction. On telecommunications, Korea will relax foreign ownership requirements, allowing 100 percent indirect ownership within two years after the entry into force of the FTA. EU satellite broadcasters will be able to operate directly cross-border into Korea and avoid having to liaise with a Korean operator. EU shipping companies will have full market access and the right of establishment in Korea as well as non-discriminatory treatment in the use of port services and infrastructure. Korea will abolish the existing subcontracting requirement for construction services. EU financial companies will have substantial market access to Korea and be able to freely transfer data from their branches and affiliates to their headquarters. EU law firms will be able to open offices in Korea to advise foreign investors or Korean clients on non-Korean law. Law firms will be allowed to form partnerships with Korean firms and recruit Korean lawyers to provide ‘multijurisdictional’ services (European Commission, 2010b).

The EU-Korea FTA will offer the opportunity to expand procurement opportunities to public works concessions and ‘Built-Operate-Transfer’ (BOT) contracts not yet covered by the Government Procurement Agreement (GPA) commitments. Such contracts are important to European suppliers who are recognised global leaders in this area. The EU-Korea FTA includes developed provisions on copyright, designs and GIs which serve as a complement and up-date to the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Agreement. The EU-Korea FTA also contains a section on enforcement of IPRs based on the EU’s internal rules in the enforcement directive. The protection and enforcement of IPR is critical to European competitiveness, and therefore the EU and Korea have agreed on an ambitious Intellectual Property chapter. EU wines, spirits, cheese and hams are very famous in Korea. The EU-Korea FTA will offer a high level of protection for commercially important GIs such as Champagne, Scotch or Irish whiskey, Manchego or Parmigiano Reggiano cheese, Vinho Verde or Tokaji wines as well as those from the Bordeaux and Rioja and many other regions like the Murfatlar vineyard, and so on. The EU-Korea FTA will offer the protection of about 160 major EU GIs directly at the entry into force of the agreement. All agricultural GIs, and not only those relating to wines and spirits, will be protected at the same high level. Both parties are committed to protect additional GIs through a procedure envisaged in the agreement. The EU and Korea agreed to prohibit and sanction certain practices and transactions involving goods or services which distort competition and trade between them. Anti-competitive practices such as cartels or abusive behaviour by companies with a dominant market position and anti-competitive mergers will not be tolerated and be subject to effective enforcement action, because they cause consumer harm and higher prices. The EU and Korea agreed to establish shared commitments and a framework for cooperation on trade and sustainable development. The EU-Korea FTA enables close dialogue and continued engagement between the EU and Korea in the fields of environment and labour. On environment, there is a commitment to effectively implement all multilateral environment agreements to which they are party. On labour, a shared commitment is included to the International Labour Organisation (ILO) core labour standards and to the ILO decent work agenda, including a commitment to ratify and effectively implement all conventions identified as up to date by the ILO (European Commission, 2010b).

The EU-Korea FTA has been in force since 1 July 2011. The EU-Korea FTA is the first of the new generation FTAs that went further than ever before at lifting trade barriers and making it easier for Korean and European firms to do business together. As the FTA has reduced import tariffs for European products at the Korean border, it is estimated that EU firms have already achieved cash savings of EUR 350 million in duties after just nine months. In the first nine months of implementation of the EU-Korea FTA EU exports to Korea increased by EUR 6.7 billion or 35 percent compared to the same period since 2007. EU exports to other countries also increased during this timeframe (by 25 percent), but the level of export increase to Korea (35 percent) shows that the early tariff eliminations are already having some effect (European Commission, 2012).

These incremental improvements are also confirmed by the fact that EU exports to Korea have grown faster in areas where the tariff was eliminated or partially removed under the EU-Korea FTA. Exports of products in areas where the tariff was eliminated on 1 July 2011 (such as wine, some chemical products, textiles and clothing, iron and steel product, machinery and appliances, representing 34 percent of EU’s exports to Korea) grew by EUR 2.7 billion or 46 percent. Exports of products in areas where the tariff was only partially liberalised on 1 July 2011 (such as cars and agricultural products, representing 44 percent of EU’s exports to Korea) increased by EUR 3 billion or 36 percent. Exports of products where there was no change to the tariff (such as some agricultural products, representing 18 percent of EU’s exports to Korea) increased by EUR 1 billion or 23 percent. This indicates that exports of the products influenced by Korea’s tariff liberalisation in the EU-Korea FTA grew EUR 1.7 billion more than they would have done otherwise. Exports of some specific products have increased faster than the average. Exports of pork increased by about 120 percent, which implies new trade of about EUR 200 million. Leather bags and luggage exports are up by over 90 percent, worth EUR 150 million of extra trade. EU produced machinery used for the manufacturing of semiconductors increased by 75 percent, representing EUR 650 million in additional exports. EU car exports went up by over 70 percent, which indicates new trade of EUR 670 million (European Commission, 2012). With the on-going Eurozone crisis and the consequent fall in the purchasing power of most EU member countries, the EU-Korea FTA during the first nine months of its implementation so far has proved more beneficial for the EU in terms of trade balance (Kim, 2011). However, when we consider that most of the tariff benefits will only be measured after a longer time period and most of the regulatory changes have yet to be implemented, the trade benefits of the agreement can only be measured with certainty after five or ten years.

The EU-Korea FTA is expected to generate mutual economic benefits and offer enormous business opportunities to both Korea and the EU. By 1 July 2016, 98.7 percent of the import duties of the EU and Korea in trade value for both industrial and agricultural goods will be eliminated. In July 2031, 99.9 percent of EU-Korea bilateral trade will be duty free. Overall, only a limited number of agricultural products are excluded from tariff elimination (European Commission, 2012). Even though the EU-Korea FTA is expected to produce substantial economic benefits for the Korean economy, it is only a framework on the trade relations between Korea and the EU. Therefore, it is more essential to develop how to actually utilise the FTA.

The EU-Korea FTA is the first of the new generation of FTAs which were promoted under the Global Europe Strategy adopted in 2006. The FTA achieved the mandates of the Global Europe Strategy by securing access to Korea’s dynamic market where European companies can compete on equal standings vis-a-vis local and other foreign companies. As the first FTA the EU concluded with an Asian country, the EU-Korea FTA will help the EU secure a foundation in a rapidly growing Asian market. The value of the EU-Korea FTA is likely to extend beyond the sphere of trade and investment and lay a sound institutional framework to the new relationship between Korea and the EU by establishing a strategic partnership between them.

The EU-Korea FTA is likely to have a strong effect on the Korean competitors in the EU market. Korean companies that compete fiercely with their competitors in the EU market will benefit from the price advantage due to the EU-Korea FTA. Korean manufacturers of cars, textiles, wireless telecommu-nications devices and chemical products are likely to increase their exports to the EU market under the EU-Korea FTA. The EU-Korea FTA will improve the Korean companies’ position in the EU market by placing their competitors at a disadvantage.

The Lisbon Treaty widens the scope of the CCP by including trade in services and FDI and simplifying the provision of the uniform protection of IPRs. Under the Lisbon Treaty, some noteworthy changes were ntroduced for the CCP including more efficient decision-making processes, a greater role for the European Parliament, and more coherence in the EU’s external actions.

The Global Europe Strategy is an ambitious agenda devised in order to increase the contribution of CCP to growth and jobs in the EU. In a rapidly changing global economy, it tries to build a more comprehensive, integrated, and forward-looking external trade policy that makes a stronger contribution to the EU’s competitiveness. It adapts the tools of the EU CCP to meet new challenges, to engage new partners, and to ensure the EU remains open to the world and other markets open to the EU.

The EU-Korea FTA is the first of the new generation of FTAs under the Global Europe Strategy. The EU-Korea FTA has been in force since 1 July 2011. Even though the trade benefits of the EU-Korea FTA can only be measured with certainty after five or ten years, the agreement is expected to generate mutual economic benefits and offer enormous business opportunities to both Korea and the EU. The value of the EU-Korea FTA is likely to extend beyond the sphere of trade and investment and lay a sound institutional framework on a particularly close relationship between Korea and the EU by establishing a strategic partnership between them.