An Airy beam is a nonspreading wave that propagates along a ballistic trajectory without any external force. Since Berry and Balazs illuminated this strange characteristic of the Airy wave packet in quantum mechanics [1], interest in Airy beams has steadily increased [2-18].

Although it is impossible to implement ideal Airy beams because they carry infinite power, so-called finite Airy beams can be achieved by tailoring infinite side lobes with an aperture function; these finite beams have propagation characteristics similar to those of ideal Airy beams, as was first shown by Siviloglou and Christodoulides [2]. Based on their report, the first optical observation of Airy beams was realized by an optical Fourier-transform system that imposed cubic phase on a broad Gaussian beam [3]. According to the same principle, nonlinear generation of Airy beams [4], curved plasma channel generation [5], and electron-beam generation [6] were reported. Another way to generate a finite Airy beam, which directly assigns the initial launching conditions, was also suggested [7]. By matching initial intensity and phase distributions of Airy beams with those of surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs) after passing through metal slits or gratings, (1+1)-dimensional ((1+1)D) Airy beams can be launched. Also, an Airy beam generated in free space can be coupled via periodic gratings on a metal surface and dynamically controlled by changing the position of either the objective lens or phase mask [8].

In this paper, we propose holographic generation of finite Airy beams by “reading” a hologram that is recorded as the interference between a finite Airy beam, generated by optical Fourier transform, and a reference plane wave [9]. Although bulk optical components are necessary in the initial recording process, once the initial recording is over we can generate finite Airy beams using only a simple plane wave. Moreover, this method can exploit the unique features of holography itself, such as successful reconstruction even with imperfect incidence of the reference beam, and multiplexing of several Airy beams.

This paper is organized as follows. After a brief introduction to Airy beams in Section II, in Section III we show that the holographically generated beam maintains non-diffracting nature with a bending trajectory, as well as self-healing. Finally, in Section IV, using the characteristics of holography, we present angular multiplexing of two Airy beams determined by the angles of reference beams.

II. THEORETICAL ANALYSIS OF AIRY BEAMS

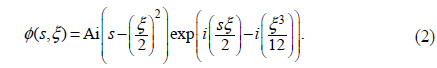

Let us invoke the solution of a (1+1)D Airy beam from the paraxial Helmholtz equation with the potential-free condition:

where

Since Eq. (2) is not square-integrable, an aperture function exp(

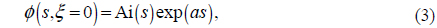

where

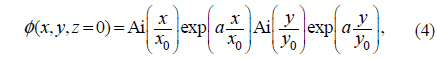

In the case of a (2+1)-dimensional ((2+1)D) finite Airy beam, Eq. (3) can be expanded to

where

III. HOLOGRAPHIC RECORDING AND RECONSTRUCTION OF AIRY BEAMS

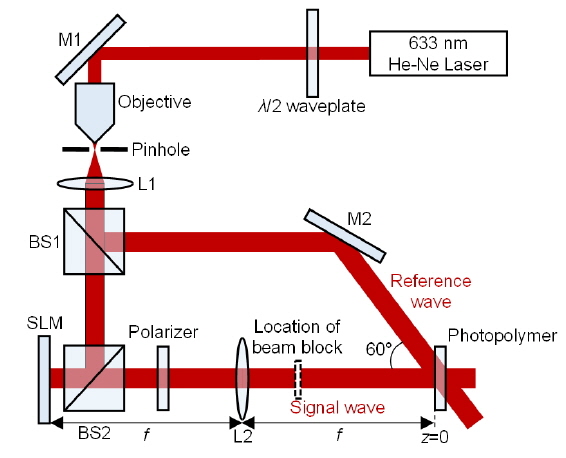

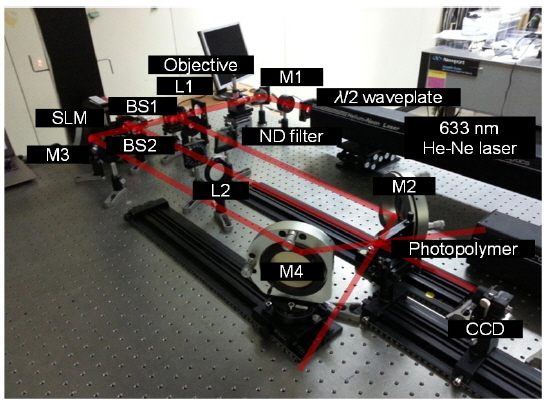

Holography is a technique that can record and reconstruct both the amplitude and the phase of an optical wave [19]. Figure 2 is a schematic diagram of the recording procedure for holographic generation of an Airy beam. After passing through expanding optics and a beam splitter 1 (BS1), a plane wave from a He-Ne laser (Research Electro-Optics, LSRP-3501) with wavelength 633 nm is divided into signal and reference arms. The signal arm is consisted of a 2-

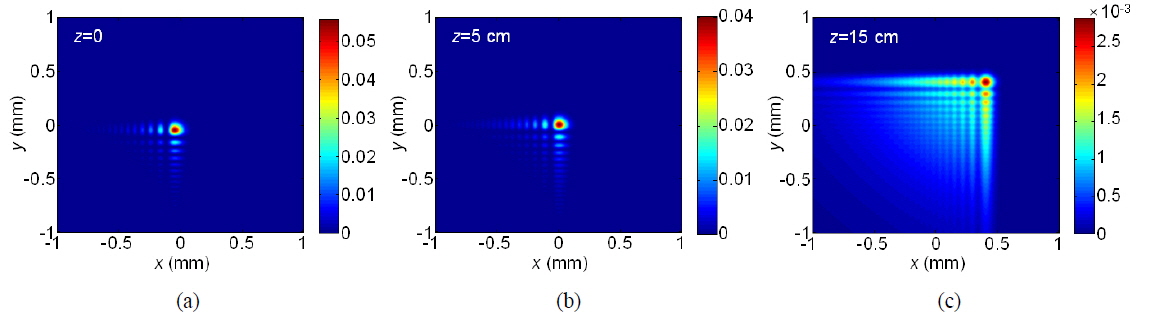

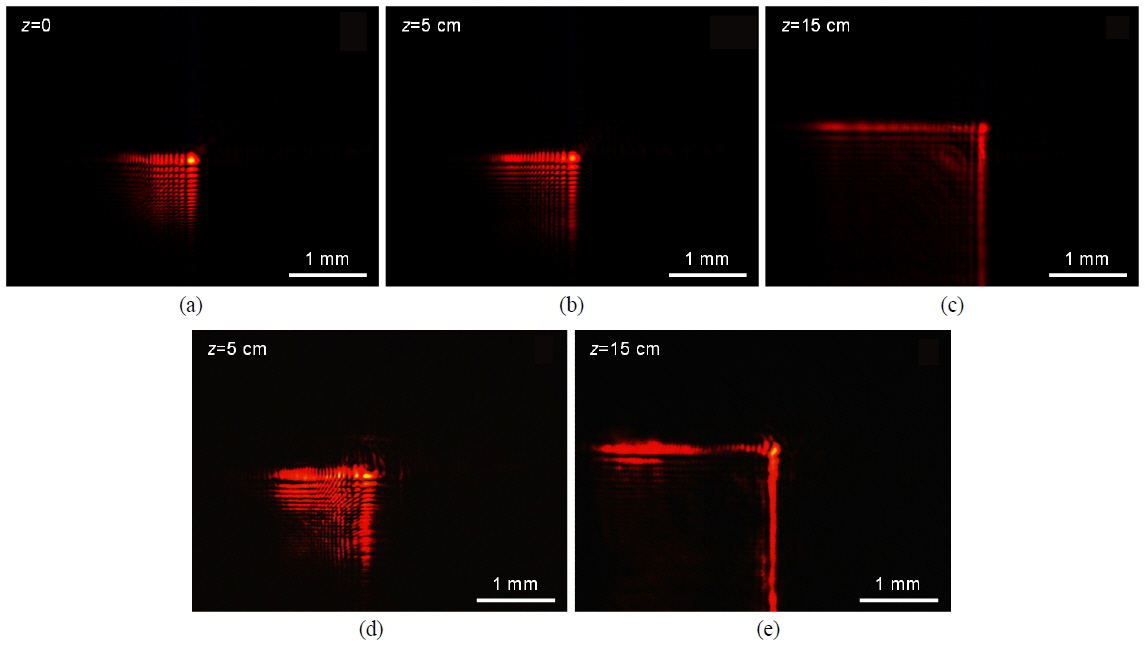

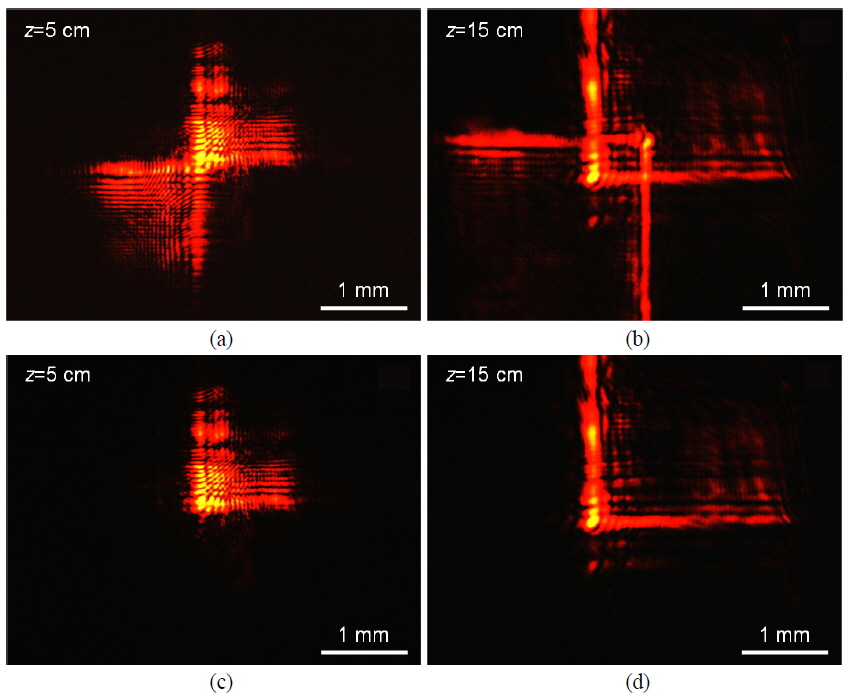

Before actually recording, we confirm that the signal beam is the desired finite Airy beam using a charge-coupled device (CCD). We use a first-order diffracted beam from the SLM for Airy beam generation and hologram recording, to avoid the DC term in the zeroth-order diffracted Airy beam. The captured images (without photopolymer) of a (2+1)D finite Airy beam at

To reconstruct the Airy beam, we place a beam blocker (indicated as a dotted box in Fig. 2) in the signal-beam path, to shine the reference beam without a signal beam. As a result, the signal beam, i.e. the (2+1)D finite Airy beam, is simply generated from the photopolymer without any SLM or lens optics. Captured intensity distributions of the reconstructed beam at

To provide a quantitative analysis of the propagation behaviors of SLM-generated Airy beams and reconstructed Airy beams, cross-correlations with the ideal Airy beam are calculated from the cross-sections of the main lobes along the

where

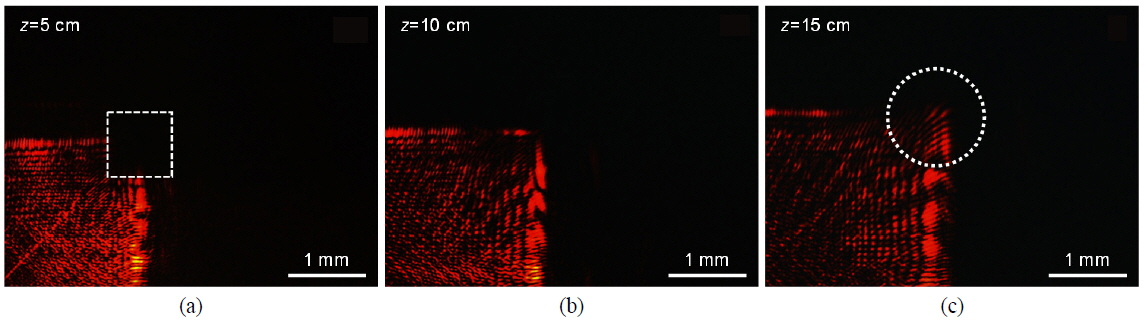

As another confirmation, we can check whether the holographically reconstructed beam has the self-healing feature [11], a distinguishing property of various types of diffractionfree beams. Here we consider two cases of self-healing in the reconstruction procedure. First, an opaque obstacle is placed between the photopolymer and the

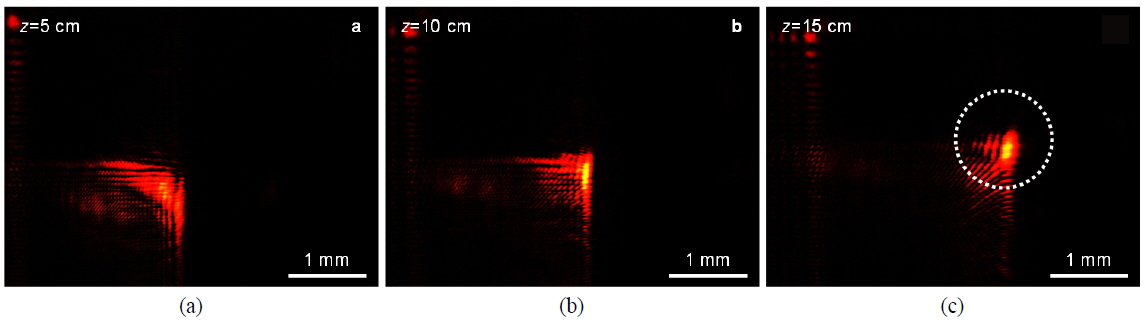

As a second case, we partially block the reference beam with an obstacle placed between M2 and the photopolymer, to achieve partial illumination of the recorded medium. The CCD image of the reconstructed beam at

IV. ANGULAR MULTIPLEXING OF AIRY BEAMS

Finally, we investigate the feasibility of angular multiplexing of Airy beams based on holography. In this case the recording procedure is conducted twice, with two reference beams at different incidence angles. In Fig. 6 the experimental setup for Airy beam multiplexing is presented. Two reference beams are incident to the photopolymer with 60° and −60° incidence angles respectively, and energy density of 32 mJ/cm2 is dosed as in the previous section. To compensate for the power difference between two reference beams, a neutral density (ND) filter is located in reference arm 1. Here reference arms 1 and 2 pass through M2 and M4 respectively. First, a (2+1)D finite Airy beam with

To reconstruct recorded Airy beams, we place an additional barrier between lens and photopolymer, to block the signal beam. After that, two reference beams are incident upon the photopolymer at the same time, and we obtain two Airy beams accelerating in opposite directions, as shown in Figs. 7(a) and 7(b), which are captured by the CCD at

In this paper, a novel Airy beam generation method based on holography is presented. The proposed method has the advantage that once holograms are recorded in the photopolymer, bulky optics such as SLM and lenses are not needed to generate Airy beams. In addition, multiple Airy beams can be stored and reconstructed simultaneously or individually. We hope that these results find practical uses, such as in particle manipulation or optical signal processing [14-18].