Since ages, humans have relied on nature for their basic amenities like comestibles, shelters, clothing, means of transportation, fertilizers, flavours, and fragrances, and not the least, medicines (Gurib-Fakim, 2006). Medicinal plants have formed the basis of sophisticated traditional medicinal practices, which have been used for thousands of years by people in China, India, Africa, and the rest of the world (Sneader, 2005). Early humans acquired the knowledge on plants’ therapeutic values through many years of vigilant observations, experience and trial and error experiments (Karunamoorthi et al., 2013a, 2012; Martin, 1995; Sofowora, 1982). Plant kingdom remains to be a repository of modern medicine due to their rich resource of bio-active molecules and secondary metabolites. Since time immemorial, each and every society has had their unique way of indigenous health practice system by using plants as a curative source to treat various ailments. However, the Chinese, Indian, and African traditional systems of medicine are globally renowned (Karunamoorthi et al., 2012).

>

Ethiopia: A cradle of medicinal plants

The Ethiopian highlands, which are the most extensive of the African mountain region, are presumed to be covered by mountain forests. Historically, they have been coined as the water tower of east and northeast Africa - a notion, which refers to the fact that a number of rivers have their sources in the highlands. The Afromontane forests of Ethiopia, render ecological, socioeconomic and medicinal significance for the humankind. Ethiopia is rich in biodiversity with high endemism. The richness in flora and fauna is a reflection of the diverse ecological setting, climate and topography found in the country. The Ethiopian flora is estimated to contain 6500 to 7000 species of higher plants, of which about 12 percent are endemic. The country has the fifth largest flora in tropical Africa (Mekonnen and Hailemariam, 2000). Plants have been used as a source of medicine in Ethiopia from time immemorial to treat various ailments (Karunamoorthi and Tsehaye, 2012).

>

Tinjute: An Ethiopian medicinal plant

Genus

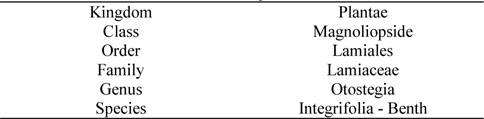

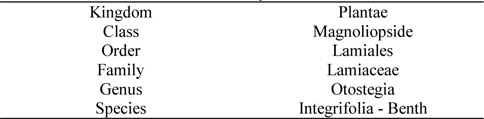

[Table 1.] Scientific classification of Tinjute

Scientific classification of Tinjute

>

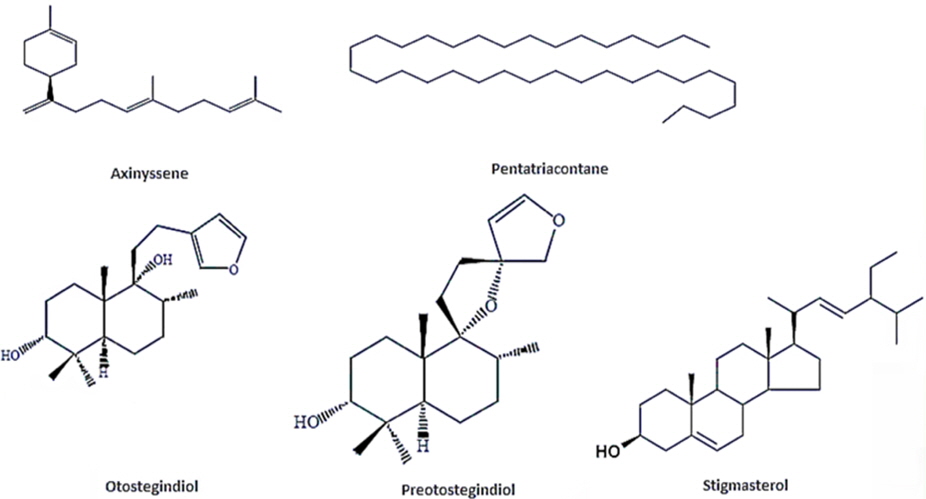

Chemical constituents of Tinjute

The essential oil and chloroform extract of air-dried leaves of

>

As an insect repellent plant

Over decades, the vector-borne diseases impose a serious public health concern to human beings in terms of considerable morbidity and mortality. The concomitant effects of global warming linked with climate change has further fueled the emergence and resurgence of several insect-borne diseases like malaria, plague, filariasis, trypanosomiasis, leishmaniasis and many arbo-viral diseases particularly dengue fever, yellow fever and chikungunya fever (Karunamoorthi, 2013). They account for nearly 17% of the global burden of infectious diseases (WHO, 2006). Besides, they also impose severe negative socioeconomic impact in the endemic regions (Karunamoorthi and Sabesan, 2009). Therefore, it is mandatory to minimize the global burden of these diseases by applying appropriate integrated vector control strategies and personal protection interventions.

An insect repellent is a substance applied to skin, clothing, or other surfaces to keep away insects from landing or climbing on that surface. The primary aim of the repellent usage is to reduce the man-vector contact and eventually to minimize the considerable annoying biting nuisance and disease transmission (Karunamoorthi and Sabesan, 2009). Repellents can be neither chemical nor natural (plant-based) and they are very supportive whenever and wherever other sorts of personal protection interventions are ineffective, unfeasible and impracticable (Karunamoorthi and Sabesan, 2010; Karunamoorthi et al., 2014). It is important to note that the existing synthetic repellents are usually inaccessible as well as unaffordable. Besides, they also pose a high level of residual toxicity and adverse side-effect (Karunamoorthi, 2011) for infants and elderly people and a few of them needed electricity also for their usage (Karunamoorthi et al., 2008a).

Since ancient time plants have been used to repel or kill the blood-sucking insects (Karunamoorthi et al., 2008b). Plant-based repellent products are easily available, locally known, and culturally acceptable (Karunamoorthi et al., 2010a). In Ethiopia, the rural population has often been using these plantbased materials as repellents by means of smoldering the dried plant parts (leaves, stem, root, bark and resin) on the traditional charcoal stove in the early evening to minimize the man-vector contact (Fig. 2). It is interesting to note that these low-cost repellant materials are abundantly obtainable in almost all the Ethiopian markets (Fig. 3). Ethnobotanical surveys in Ethiopia (Karunamoorthi et al., 2009a, b; Kidane et al., 2013; Teklay et al., 2013) and Eretria (Waka et al., 2004) found that the local residents have been using

In Ethiopia, an experiment was conducted by applying the smoke into the repellent “test” mosquito cage by direct burning of 25gm of dried leaves of

The

>

As a traditional phytotherapeutic agent

Over centuries, cultures around the world have learnt the usage of medicinal plants to fight against illness and to maintain good health. In the resource-limited settings, these plants are one of the longest-serving companions for the rural poor due to their easier accessibility and affordability (Karunamoorthi et al., 2013; Roberson, 2008). Despite the recent scientific advancement and globalization, the system of traditional medicine and complementary/alternative medicine is considered to be a primary health care modality in the resource-constrained health care settings (Roberson, 2008). The WHO estimates that, even now more than 80% of the world’s population relies on traditional healing modalities and herbals for primary health care and wellness (WHO, 2002). The heavy reliance on medicinal plants is partly owing to the high cost of modern drugs, limited or inaccessibility of modern healthcare facilities (Cunningham, 1993; WHO, 2003).

In the past, the importance of traditional medicinal plants and their phytotherapeutic values have often been disregarded and undervalued. However, in the recent years the revitalization and renewed interest on medicinal plants has been well-observed among the health conscious public and scientific community (Karunamoorthi et al., 2012), due to the long-term adverse consequences of modern chemotherapeutic agents. In Ethiopia, 70% and 90% of human and livestock population depend on the traditional system of medicine, respectively (Bekele, 2007).

Malaria continues to be a major global public health problem and about 3.3 billion people are at the risk in 104 endemic countries. It remains to be one of the important causes of maternal and childhood morbidity and mortality in sub-Saharan Africa and particularly Ethiopia (Karunamoorthi et al., 2010b).It is a disease of poverty and a cause of poverty which inflicts a serious negative impact on global public health and it has also hampered socioeconomic development among the poorest countries of the world (Karunamoorthi, 2012b).Globally, over thousand plants have been used as potential antimalarials in the resource-poor settings due to fragile/limited health-care systems, which quite often fail to meet the expectations of the needy poor people (Karunamoorthi et al., 2013b).

At the moment, there is a growing acceptance and keen interest towards traditional system medicines and it has led many researchers to concentrate on traditional antimalarial phytotherapy. Furthermore, the existing potent antimalarial artemisinin combination therapy is critically short supply unaffordable and inaccessible too. The recent reports suggest the emergence and spread of

In Ethiopian traditional medicine, the leaves of

The genuine antiplasmodial activity along with its safety profile observed in the study could make the leaf extract of

Though many believe that the usages of medicinal plants are relatively safe, which have folklore reputations for antimalarial properties, many herbs may also be potentially toxic due to their intrinsic adverse side-effects. Therefore herbal-derived remedies need a powerful and deep assessment of their pharmacological qualities in order to establish their mode of action, safety, quality and efficacy. World-wide, over thousand plant species have been used as a source of traditional antimalarial phytotherapy for many centuries and in the future, plant-derived compounds will still be an essential aspect of the therapeutic array of antimalarials. However, their clinical efficacy, quality and safety need to be scientifically evaluated and proved (Karunamoorthi et al., 2013b).

>

Other medicinal properties of Tinjute

Research has indicated that one of the chemical constituents of

>

Miscellaneous purposes in Ethiopia

Though utilization of medicinal plants is not a new phenomenon, now there is more consciousness among the people about the adverse effects of synthetic products as well user-friendly nature of plant-based products than ever before. In Ethiopia,