Nitrate flux from upland ecosystems to surface and groundwater is a major environmental concern (Prasad and Power 1995, Nolan et al. 1997). Excessive fertilizer utilization and livestock waste disposal from agricultural ecosystems are primary sources of nitrogen pollution (Galloway et al. 2004), so aquatic ecosystems near agricultural activities can be susceptible to nitrate pollution (Vitousek et al. 1997). However, nitrate can be permanently removed from aquatic ecosystems by denitrification that removes up to 50% to 60% of incoming nitrate in agricultural streams (Green et al. 2004). Thus, construction of denitrification walls, which supplies sufficient carbon to denitrifiers and controls the velocity of stream flow, is often suggested as a way to reduce nitrate concentrations from agricultural stream ecosystems (Schipper et al. 2005).

A denitrification wall is a permeable wall perpendicular to groundwater flow and stimulates denitrification activity, reducing nitrate concentrations in the wall by adding organic carbon substrates (Schipper and Vojvodić-Vuković 2001). Generally, denitrification walls use various organic materials as carbon substrates including sawdust (Robertson et al. 2000, Schipper and Vojvodić-Vuković 2000), tree bark, wood chips, leaf compost (Blowes et al. 1994), soybean oil (Hunter et al. 1997), and papers (Volokita et al. 1996). Addition of organic substrates to denitrification walls resulted in removal of 60% to 100% of added nitrate during their first year of operation (Robertson and Cherry 1995), and treating sediments with sawdust decreased in their nitrate concentrations (Schipper and Vojvodić- Vuković 1998, 2001). However, information on the relachromatotionship between organic substrate characteristics and denitrification rates is rare. Only one study reported that application of cornstalks with a C:N ratio of 42 showed a higher efficiency of nitrate removal in denitrification walls than that of wood chips with a C:N ratio of 795 (Greenan et al. 2006). In addition, previous researches have compared nitrate concentrations before and after addition of carbon substrates to denitrification wall, rather than measuring actual denitrification and carbon mineralization rates. Thus, main objective of this research was (1) to investigate how addition of different types of organic substrates to riparian sediments affected denitrification and carbon mineralization rates and specifically (2) to examine if quality and quantity of added organic substrates were the main regulators for determining denitrification rates in tributary ecosystems.

>

Site descriptions and sampling

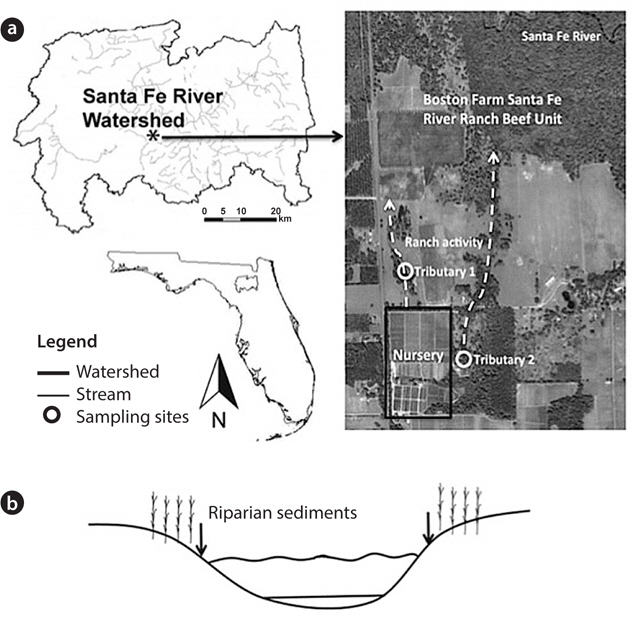

The study site was riparian sediment from tributaries at the Boston Farm Santa Fe Ranch Beef Unit Research Center in the Santa Fe River Watershed, Alachua County, FL, USA. Land uses on this site include a low-intensity cattle operation with about 300 heifers on 648 ha (1 ha = 104 m2) and a nursery operation (Holly Factory Nursery) (Frisbee 2007). Tributary 1 (T1; N 29°55′33″, W 82°30′14″) runs through a pasture ecosystem vegetated with trees and grasses (

>

Analyses of chemical properties

For analyzing the chemical properties of organic substrates, 1 g of each organic substrate and 1 g of riparian sediment was extracted by using 0.5-M K2SO4, respectively (Bundy and Meisinger 1994), and the filtered solution was analyzed for extractable organic carbon (Ext. Org C) by using a Shimadzu TOC-5050A Total Organic C Analyzer equipped with an ASI-5000A auto sampler (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Subsamples of each organic substrate and riparian sediment were dried at 70°C for 3 days, and then the total carbon (TC) and total nitrogen (TN) in them were measured by using a Flash EA 1112 Series NC Soil Analyzer (Thermo Electron Corporation, Waltham, MA, USA) (Nelson and Sommers 1996).

>

Denitrification and carbon mineralization rates

Ten grams of riparian sediment with selected organic substrate (litter collected from the T1 and T2 sites, yard waste, hardwood oak chips, and softwood sawdust) was added to separate 160‑mL serum bottles and purged with pure N2 gas to create anaerobic conditions. Sediments amended with litter or organic substrates were incubated at 24°C in a Model 25 incubator shaker at 150 rpm (New Brunswick Scientific, Enfield, CT, USA).

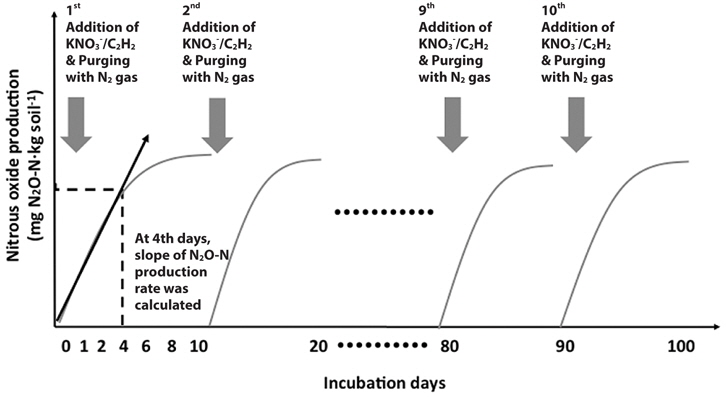

In detail, after 1 day of pre-incubation, the T1 riparian sediment was amended with litter collected from the T1 site at rate of 4 g carbon (kg dry sediment)‑1. The T2 riparian sediments were amended with each organic substrate (litter, yard waste, hardwood oak chips, and softwood sawdust) at rate of 4 g carbon (kg dry sediment)-1. Serum bottles were flushed with pure N2 again to create anaerobic conditions. To determine denitrification rates, 20 mL of acetylene gas (12.5%) was added to one set of bottles (Tiedje 1988). Acetylene gas was not added to a second set of bottles for analyzing anaerobic carbon mineralization rates because acetylene addition can disturb the CO2 measurement. KNO3 solution equivalent to 200 mg NO3--N (kg dry sediment)-1 was added to sediments by using a syringe. The reason why higher than reference level of NO3--N was added to riparian sediments was to create the conditions for denitrifiers to consume more organic substrates as possible under non-nitrate limited conditions. Headspace gas (100 μL) was collected at 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 days and analyzed for N2O and CO2. The N2O and CO2 concentrations in the headspace were measured by using an electron capture detector-equipped gas chromatograph (ECD GC-14A; Shimadzu) and thermal conductivity detector (TCD) GC 8A (Shimadzu), respectively. After 10 days, bottles were flushed with pure N2. KNO3 solution equivalent to 200 mg NO3--N (kg dry sediment)-1 and 20 mL of acetylene gas (12.5%) was added again to samples. Sampling and analysis were repeated as described above. KNO3 amendment was repeated at 10-day intervals for 100 days. At the 4th days, the slopes of N2O-N (potential denitrification rate) and CO2-C (carbon mineralization rate) production rates were calculated because N2O gas production was not linearly increased after 4 days (Fig. 2).

Statistical analyses were conducted by using JMP ver. 10 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). One‑way analysis of variance tests (ANOVA) were performed to investigate differences in chemical properties, denitrification, and carbon mineralization rates between sites and among substrate treatments. Least significant difference at the 5% confidence level was used for comparisons. Regression analysis was used to quantify the relationship between denitrification rates and chemical properties.

>

Chemical properties of organic substrates

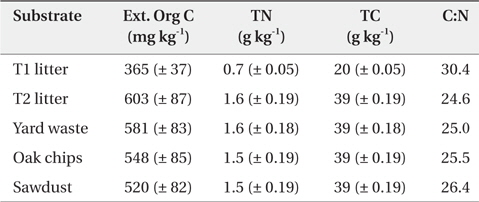

At the initial incubation experiments, the Ext. Org C concentration of riparian sediment treated with organic substrate was highest in the T2 site litter treatment followed by yard waste, oak chips, sawdust, and T1 site litter treatments; however, TC and TN concentrations of riparian sediment treated with organic substrate was not significantly different among the substrate types except for the sediment treated with T1 site litter (Table 1). The C:N ratio of riparian sediment amended with organic substrate was highest in the T1 site litter treatment followed by sawdust, oak chips, yard waste, and T2 site litter treatments (Table 1).

Chemical properties* in riparian sediments treated with various organic substrates before incubation experiment

>

Denitrification and C mineralization rates

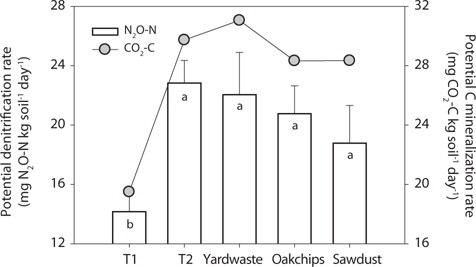

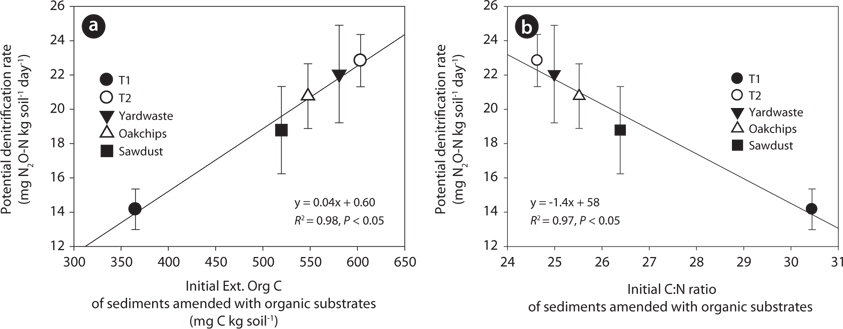

The T1 site treated with litter showed the lowest potential denitrification rates (i.e., mg N2O-N·(kg soil)-1 day-1) and anaerobic carbon mineralization rates (i.e., mg CO2-C·(kg soil)-1 day-1). However, in the T2 riparian sediments, potential rates of the substrate treatments did not differ significantly in substrate types (Fig. 3). To further investigate factors regulating denitrification rate, regression analysis predicting denitrification rate was performed with biogeochemical parameters as predictors. Initial concentrations of Ext. Org C in sediments amended with organic substrates were strongly positively correlated with denitrification rate (Fig. 4a;

Typically, high rates of anaerobic carbon mineralization lead to a high denitrification rates because decomposition of organic matter consumes more nitrate than oxygen and reduces the nitrate to nitrogen gas under anaerobic conditions (de Catanzaro and Beauchamp 1985, Paul and Beauchamp 1989). Previous research also showed positive relationships between nitrate consumption and anaerobic carbon mineralization rates (Reddy et al. 1982), and our results were consistent with this tendency. However, under N-limited conditions, the added carbon substrate is difficult to be decomposed by denitrifiers because of less supply of electron acceptors (nitrate) to denitrifiers (Aulakh et al. 1991, Reddy and DeLaune 2008). In addition, high carbon to nitrate ratio induced by carbon substrate addition can create the favorable matericonditions for dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium (DNRA) microbes capable of dissimilatory reducing nitrate to ammonium, which can cause to inhibition of nitrate reduction to nitrogen gas because of over-competition for nitrate uptake between denitrifiers and DNRA microbes (Binnerup et al. 1992). Thus, addition of carbon substrate to increase denitrification rates might be significantly effective when organic carbon is limited and nitrate is abundant.

The positive relationship between denitrification rate and Ext. Org C concentrations in sediments amended with organic substrates indicates the important influence of available carbon on denitrification rates. In previous research, the level of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) was positively correlated with denitrification activity in stream water (Seitzinger et al. 2006), stream sediments (Martin et al. 2001), river floodplains (Baker and Vervier 2004), groundwater (Hill et al. 2000), and wetland soils (Hayakawa et al. 2006). In addition, DOC of stream water and sediments were mainly originated from the leached carbon from leaf-litter and plant detritus, showing that DOC concentration in the water body was directly related to carbon contents of leaf-litter and plant detritus that are one of the main carbon sources to denitrifiers (Meyer et al. 1998, Axmanová and Rulík 2005). However, the quantity of DOC in leachates from leaf-litter and plant detritus cab be various depending on the vegetation types such as woody debris, litter in a mixed forest (Hafner et al. 2005), barks, deciduous tree litter, oak litter (Zander et al. 2007), and riparian shrubs (Sasaki et al. 2007) because of differences in their carbon structure and composition.

The negative relationship between substrate C:N ratios and denitrification rates implies that carbon quality also has an important effect on denitrification rates. In sediments that receive the same amount of carbon, organic substrate with high C:N ratio decomposes slowly, so the supply of available organic carbon to denitrifiers is low (Reddy and DeLaune 2008). In addition, microbes prefer to use labile organic carbon (i.e., those with low C:N ratios) rather than recalcitrant organic matter because degradation of complex organic matter costs more energy than uptake of labile organic carbon. Previous research also showed that wetland sediments treated with plant detritus (

In summary, the extractable organic carbon concentrations of sediments amended with organic substrates were linearly related to denitrification rates because labile organic carbon is the main energy source for heterotopic denitrifiers. However, the C:N ratio of sediment was weakly negatively correlated with denitrification rates because lower quality of organic substrate having high C:N ratio requires more energy for denitrifiers to decompose it. In addition, carbon quantity and quality of organic materials were various depending on the substrate types. Therefore, this result suggests that to increase the efficiency of organic substrates for nitrate removal in a denitrification wall, organic materials used must have high level of labile organic carbon content and low C:N ratio.