Breast cancer is the second most common cancer diagnosed in Korean women, and is continuously increasing in incidence (Nam and Kang, 2013). Despite many recent advances in anticancer agents, many patients suffer relapse and side effects (Anelli

Generally, cancer is characterized with the excessive cell growth, the lowered apoptosis, and programmed cell death inhibited (Evan and Vousden, 2001). Thus one of the best conditions for cancer treatment is to induce apoptosis of cancer cells. Apoptosis plays an important role in regulation of homeostasis of normal cells and cell proliferation. Dysregulation of apoptosis is associated with human diseases such as cancer, autoimmune disease, and defective immunity (Solary

The use of natural substances for cancer chemoprevention has been one of the most visible fields for cancer control in recent years (Wang

Silk is a well-known fibrous protein produced by the silkworm, and has been used traditionally in textile fibers and surgical sutures in human beings (Wang

In this study, we investigated whether HSF induces apoptosis through the mitochondrial pathway in breast cancer MCF-7 cells. We used DAPI staining to examine the effect of HSF on cell morphology and nuclear morphology and used flow cytometry and Western blot analysis (including Bax, Bcl-2, cytochrome C, caspase-3, and PARP) to examine its ability to induce apoptosis in MCF-7 cells through the mitochondrial pathway and to cause sub-G1 arrest.

>

Preparation of silk fibroin extracts

The raw materials were degummed twice with 0.5% on-the weight-of-fiber (OWF) Marseilles soap and a 0.3% OWF sodium carbonate solution at 100℃ for 1 h and then washed with distilled water. Degummed silk fibroin fibers (35 g) were dissolved in a mixed solution (700 mL) of CaCl2, H2O, and ethanol (molar ratio=1:8:2) at 95℃ for 5 h. This calcium chloride/silk fibroin mixed solution was filtered twice through a Miracloth (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA) quick filter. Gel filtration column chromatography on a GradiFrac system (Amersham Parmacia Biotech, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a UV-1 detector operating at 210 nm was used to desalt the calcium chloride/silk fibroin mixed solution,. A commercially available and prepacked Sephadex G-25 column (800 × 40 mm i.d. Amersham Parmacia Biotech) was used. Pure (100%) distilled water was used as the elution solvent at a flow rate of 25 mL/min; the sample injection volume was 200 mL, and the fraction volume was 30 mL. The silk fibroin was stored at -20℃ until use.

MCF-7 human breast cancer cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, VA, USA) and maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10 % FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen, CA, USA). The medium was changed every 3 d. Cells were maintained in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37℃.

>

Cell population growth assay

The MCF-7 cells were treated once with various concentrationso f HSF and observed after 24, 48 and 72 h. After completion of the treatment, MTT working solution (5 mg/mL) was added to each well and the cells were incubated at for 3 h. The supernatants were carefully aspirated, DMSO was added to each well, and the plates agitated to dissolve the crystal product. The absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a multi-well plate reader.

>

Cytotoxicity detection assay

Cell death in the culture was quantified by measuring the release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). MCF-7 cells were incubated with various concentrations of HSF 24, 48, and 72 h and then analyzed for LDH leakage into the culture medium. In brief, wells were treated with 1% Triton X-100 solution for 5 min for maximum LDH release. Cells were then centrifuged at 1,000 rpm for 3 min. LDH assay mixture was added, and mixture was incubated for 30 min. HCl (1 M) was added to stop the reaction. The absorbance was measured at 490 nm using a multi-well plate reader.

>

Analysis of nuclear morphology

After being treated with HSF, the cells were washed with PBS and KCl solution was added for 5 min at room temperature. Cells were then, fixed in fixing solution (methanol : acetic acid = 3 : 1) for 5 min twice and stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride (DAPI, Fluorpure grade) for 10 min at room temperature in the dark. The cells were washed twice with PBS and imaged using a fluorescence microscope (ZEISS, Axiovert S100).

After being treated with HSF, the cells were washed with ice-cold PBS, and centrifuged at 110 g for 5 min. The cells were fixed in ice-cold 70% ethanol at 4℃ for at least 30 min, and then incubated at room temperature in PBS containing RNAse A and propidium iodide (PI), 100 μL and 400 μL, respectively. Further analysis with a FACscan flow cytometer (BD FACSVantage SE) equipped with a 488 nm argon laser was performed. The population of cells in each cell-cycle phase was determined using Cell Quest software (BD Biosciences, France).

>

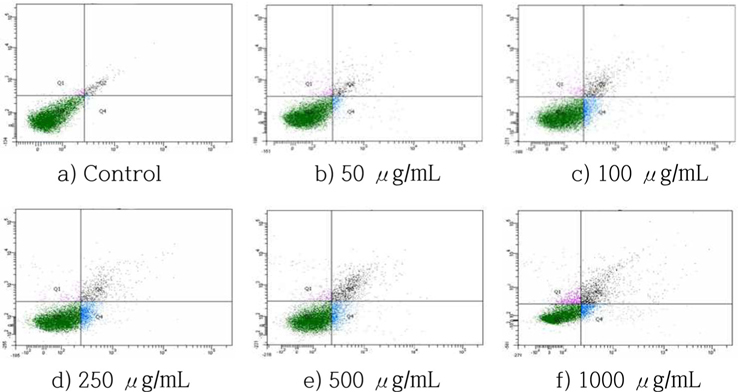

Annexin V-FITC/PI double staining analysis

Annexin V-FITC/PI double staining analysis was used to detect apoptosis and necrosis induced by HSF in MCF-7 cells. After being treated with HSF, the cells were harvested, washed with ice-cold PBS twice, and centrifuged. The cells were then stained with 100 μL Annexin V-FITC labeling solution supplemented with 20 μL Annexin V-FITC labeling reagent, 20 μL PI solution, and 1 mL incubation buffer at room temperature for 15 min in the dark. Annexin V-FITC and PI emissions were detected in the FL1 and FL2 channels of a FACScan flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) using emission filters of 525 and 575 nm, respectively. The percentages of normal (Annexin V-FITC-/PI-), early apoptosis (Annexin V-FITC+/PI-), late apoptosis (Annexin V-FITC+/PI+), and necrosis cells (Annexin V-FITC-/PI+) were calculated using Cell Quest software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

After being treated with HSF, the cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and lysed with the extraction buffer containing 20 mM Tris, pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM sodium phosphate, 100 μM sodium vanadate, 100 μM ammonium molybdate, 10% glycerol, 0.1% nonidet P-40, 0.1% SDS, and 1 × protease and phosphatase inhibitors for western blotting. Insoluble materials were removed by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 20 min. The total concentration of extracted proteins was determined using the Bradford method. The proteins in the supernatants (25 μg/lane) were separated by electrophoresis on SDS-polyacrylamide gels (SDS-PAGE, 10 - 12%) and then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Blots were blocked in 5% skim milk diluted in PBS-T buffer (PBS containing 0.5% Tween 20) for 1 h and then incubated over-night with polyclonal antibodies against Bcl-2, Bax, cytochrome c, caspase-3, PARP, and β-actin. To detect the antigen-bound antibody, the blots were treated with secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase coupled anti-IgG. Immunoreactive proteins were visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system, and band intensity was quantified by densitometry (Biomaging systems ver. 4.8, UVP Inc., CA, USA).

Each experiment was performed in triplicate and the results are expressed as the mean ± S.D. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software. Analysis of variance was performed using ANOVA procedures. Significant differences (p < 0.05) between the means were determined using Duncan’s multiple range tests.

>

Inhibition of cell viability and cytotoxicity in MCF-7 cells

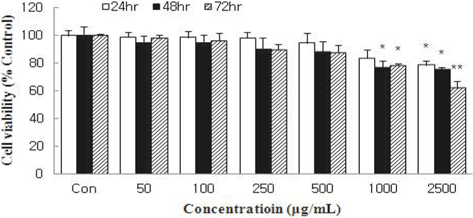

Cell viability was measured using an MTT assay and expressed as percentage cell viability compared with the control. HSF significantly reduced the cell viability of MCF-7 cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Fig. 1). Treatment with HSF at 2500 μg/mL for 48 h and 72 h inhibited cell viability by 23.2% and 36.1%, respectively.

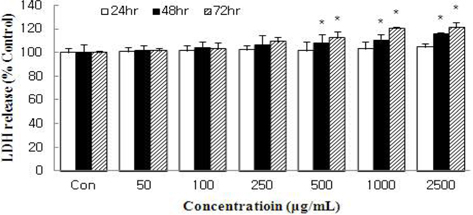

The amount of LDH released into the culture medium in response to HSF treatment was measured to evaluate the degree of injury to the MCF-7 cells. HSF caused dose- and time-dependent increases in LDH activity (Fig. 2). At 72 h, HSF at 2500 μg/mL caused LDH release ation by 20.9% compared with control. However, the inhibition did not exceed IC50 like cell viability. The results of our data demonstrate that HSF at doses of 50 ~ 1000 μg/mL did not show toxicity to MCF-7 cells.

Cells were incubated with HSF at the indicated concentrations for 24, 48, or 72 h, and the growth rate was assessed with an MTT assay. Data are expressed as percentage growth rate of cells cultured in presence of HSF, compared with untreated control cells, taken as 100%. All values are mean ± S.D. Values with different superscripts are significantly different by ANOVA with Duncan’s multiple range test at p < 0.05.

Cells were treated with HSF for 24, 48, or 72 h and the increase in the number of damaged cells was evaluated by measuring the release of lactate dehydrogenase into the culture medium. All values are mean ± S.D. Values with different superscripts are significantly different by ANOVA with Duncan’s multiple range test at p < 0.05.

>

Change in nuclear morphology

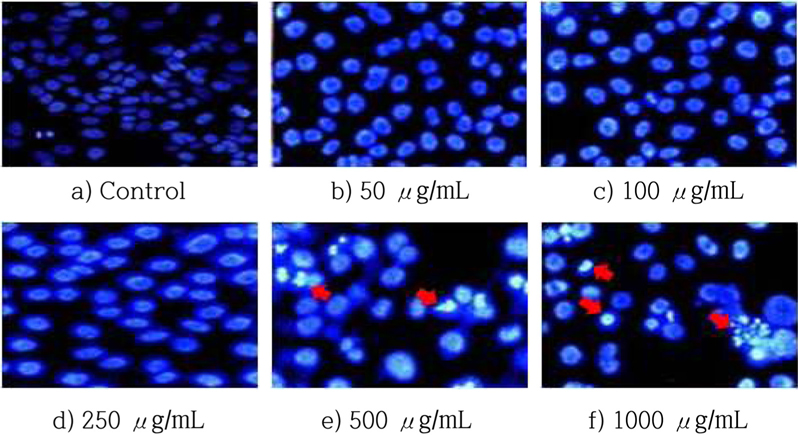

The DAPI staining assay was used to confirm that HSF-induced apoptosis. The cells were treated for 72 h at various concentrations of HSF and then examined by fluorescence microscopy. The morphological changes of apoptosis include membrane blebbing, cell shrinkage, and formation of apoptotic bodies, and all. These characteristics were after HSF treatment. The numbers of apoptotic cells increased along with the HSF dose (Fig. 3).

Nuclear morphology of MCF-7 cells treated with HSF for 48 h. After treatment followed by DAPI staining, the cells were observed under a fluorescence microscope. (magnification : 400x)

>

Effects of HSF on induction of apoptosis in MCF-7 cells

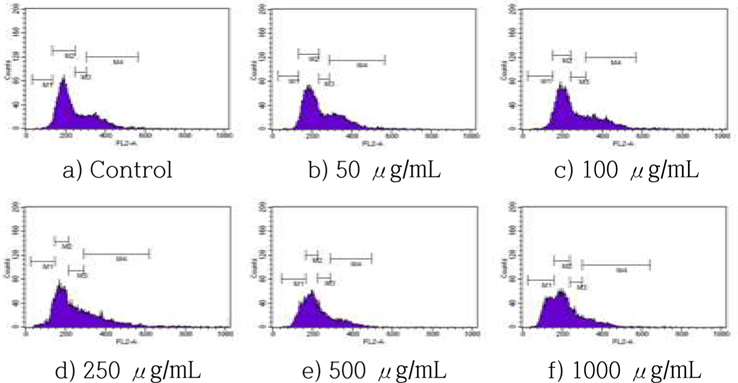

The effects of HSF on cell cycle progression were examined by incubating MCF-7 cells with various concentrations of HSF for 72 h, following by staining with PI and flow cytometry. The HSF treatment increased accumulation in the sub-G1 phase in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4), with a dose-dependent increase of cells in the sub-G1 population of >18% and 31%, respectively, after a treatment with 250, and 1000 μg/mL HSF for 72 h.

The number of apoptotic cells, including early and late apoptotic cells, increased in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5). When the treatment concentrations increased, the percentage of normal cells decreased from 97.0% (control) to 78.7% (1000 μg/ mL). The percentage of apoptotic cells (including early and late apoptotic cells) increased from 1.6% (control) to 18.2% (1000 μg/mL). These results indicated that the decrease in viable cells is due at least in part to the apoptosis-inducing effect of HSF.

Cells were incubated with HSF at the indicated concentrations for 72 h and the increase in the sub-G1 cell population was evaluated by cell apoptosis analysis. All values are mean ± S.D.

Cells were incubated with HSF at the indicated concentrations for 72 h and the increase in apoptotic cells was evaluated by Annexin-V/PI double staining analysis.

Normal (Annexin V-FITC-/PI-), early apoptosis (Annexin V-FITC+/PI-), late apoptosis (Annexin V-FITC+/PI+), and necrosis cells (Annexin V-FITC-/PI+).

>

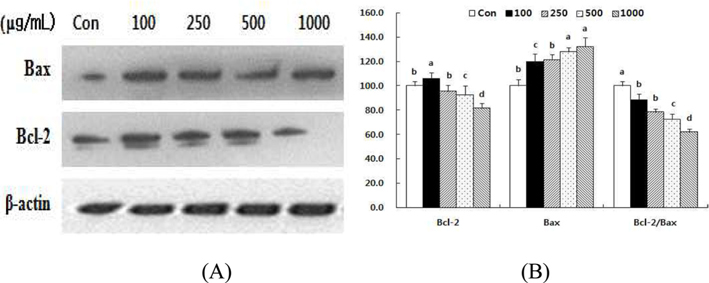

Effect of HSF on the levels of Bax and Bcl-2 in MCF-7 cells.

The cellular ratio of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 to pro-apoptotic Bax might be an important factor in regulation of the apoptotic process (Donovan and Cotter, 2004), so we evaluated the involvement of Bcl-2 and Bax in HSF-induced apoptosis. The results indicate that HSF may disturb the Bcl-2/Bax ratio. Treatment with HSF decreased the level of Bcl-2 protein in a dose-dependent manner after 72 h (Fig 6). In contrast, the level of Bax protein increased. Consequently, the Bcl-2/Bax ratio decreased by 11.7% and 38.2%, respectively, after treatment with 100 and 1000 μg/mL HSF.

Data are expressed as percentage cell death rate of cells cultured in presence of HSF compared with untreated control cells, taken as 100%. All values are mean ± S.D. Values with different superscripts are significantly different by ANOVA with Duncan’s multiple range test at p < 0.05

>

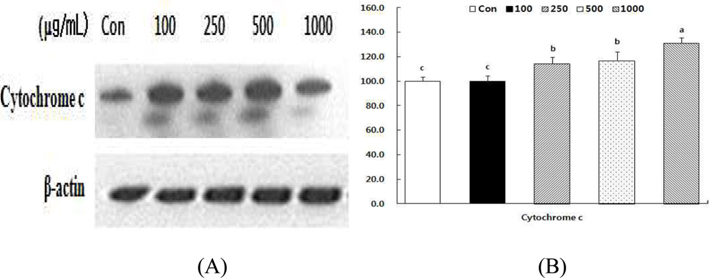

Effect of HSF on the levels of cytochrome c in MCF-7 cells.

Alteration of Bcl-2/Bax ratio stimulates the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria into the cytosol, where it helps activate caspases (Desagher and Martinou, 2000). To evaluate the effect of HSF, we examined cytochrome c release in MCF- 7 cells in response to HSF exposure for 72 h. As shown in Fig 7, the cytochrome c level increased in a dose-dependent manner after HSF treatment of MCF-7 cells.

Data are expressed as percentage cell death rate of cells cultured in presence of HSF compared with untreated control cells, taken as 100%. All values are mean ± S.D. Values with different superscripts are significantly different by ANOVA with Duncan’s multiple range test at p < 0.05

>

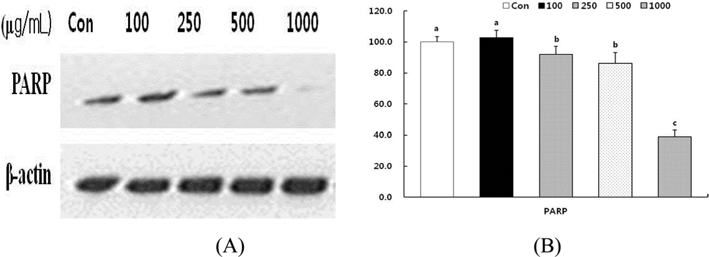

Effect of HSF on PARP cleavage in MCF-7 cells.

We examined whether the HSF–induced apoptosis was accompanied by cleavage of PARP in MCF-7 cells. PARP is specifically cleaved by caspase into an 85 kDa fragment that can be detected in apoptotic cells (Herceg and Wang, 2001). As shown in Fig. 8, treatment of MCF-7 cells with HSF results in the increase of the 85 kDa fragments relative to the intact 116 kDa protein in a dose dependent manner. The cleavage of PARP in MCF-7 cells started 72 h after treatment with HSF and became increasingly apparent over time.

Data are expressed as percentage cell death rate of cells cultured in presence of HSF compared with untreated control cells, taken as 100%. All values are mean ± S.D. Values with different superscripts are significantly different by ANOVA with Duncan’s multiple range test at p < 0.05

Natural substances have been used to prevent and treat diseases and might be new candidates for the development of anti-cancer agents (Mousavi

In our study, initiation of apoptotsis in MCF-7 cells was detected by a loss of cell viability, as confirmed by the MTT assay. HSF significantly reduced the cell viability of MCF-7 cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Fig. 1). In parallel, HSF showed a trend for a time- and dose-dependent increase in LDH activity (Fig. 2). At the concentration of 2500 μg/mL of HSF, cell cytotoxic activity was significantly higher than control, as in the MTT assay result. The MTT and LDH assays indicated that HSF inhibited the population of MCF-7 cells. The decrease in the number of viable cells could be due to an increase in necrotic cell death, induction of apoptosis, and/or impairment of the cells transition through the cell cycle. Thus, these data provide the first indication that HSF acts directly on MCF-7 cells to induce cell death.

A major goal of cancer treatment has been induction of apoptosis in cancer cells without damage to normal cells (Shim

As evidenced by Ca2+ dependent binding of Annexin V-FITC, phosphatidylserine is a membrane phospholipid that is distributed toward the intracellular leaflet of the cell membrane in normal cells but translocated to the outer leaflet of the membrane during apoptosis (Zhang

Induction of apoptosis through the mitochondrial pathway is one of the best strategies for cancer treatment. Our western blot analysis showed that HSF induced apoptosis through the mitochondrial pathway in MCF-7 cells. The mitochondrial or intrinsic pathway involves the Bcl-2 family of proteins and the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria. The ratio of two of the Bcl-2 family members, Bcl-2 and Bax protein, plays an important role in the mitochondrial pathway (Kluck

In conclusion, HSF has an anti-cancer effect in MCF-7 cells attributed to induction of apoptosis associated with cytochrome c release, PARP degradation, and disruption of the ratio of Bcl-2 and Bax protein ratio. These results confirm the potential of HSF as an anticancer and cytostatic agent in human breast cancer cells.