Chitosan is a naturally occurring mucopolysaccharide and the second most abundant biopolymer, exhibiting versatile biological properties including biodegradability, biocompatibility, and a less toxic nature. These properties make chitosan attractive for a wide variety of pharmaceutical, biomedical, food industry, health and agricultural applications (Felt et al., 1998; Kim et al., 2007; Lin et al., 2009). Moreover, chitosan has been used for the development of new physiologically bioactive materials because it exhibits versatile biological properties, including antioxidant, antibacterial, anti-cancer, antiinflammatory and immunostimulatory activities (Jeon and Kim, 2001; Park et al., 2004a; 2004b; Lee et al., 2009a, 2009b, 2011). However, its water-insolubility is a major limiting factor. Therefore, there is growing interest in developing novel chitosan derivatives with desired characteristics, including enhanced water solubility. Consequently, methods to improve not only the water solubility but also the biological activities of chitosan have been developed by using both chemical and enzymatic modifications. Typically, appropriate moieties are conjugated onto the chitosan backbone. Recently, our group developed a gallic acid-

Marine-derived bioactive molecules have been isolated and their bioavailability characterized. Phloroglucinol is a phytochemical derived from edible brown algae with antioxidant, tyrosinase-inhibiting, cytoprotective and anti-inflammatory activities (Kang et al., 2004, 2006; Heo et al., 2005; Yoon et al., 2009; Kim and Kim, 2010). Previously, we demonstrated successful conjugation of phloroglucinol onto the chitosan backbone, and the chitosan-phloroglucinol conjugate showed higher antioxidant activity

Chitosan (average MW, 310 kDa; degree of deacetylation, 90%) was donated by Kitto Life Co. (Seoul, Korea). Phloroglucinol, Folin-Ciocalteau phenol reagent, and hydrogen peroxide were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Monobromobimane (mBBr), diphenyl-1-pyrenylphosphine (DPPP), and 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFH-DA) were obtained from Molecular Probes Inc. (Eugene, OR, USA). The other materials required for cell culture were purchased from Gibco BRL, Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY, USA). All other chemicals and reagents used in this study were of analytical grade and commercially available.

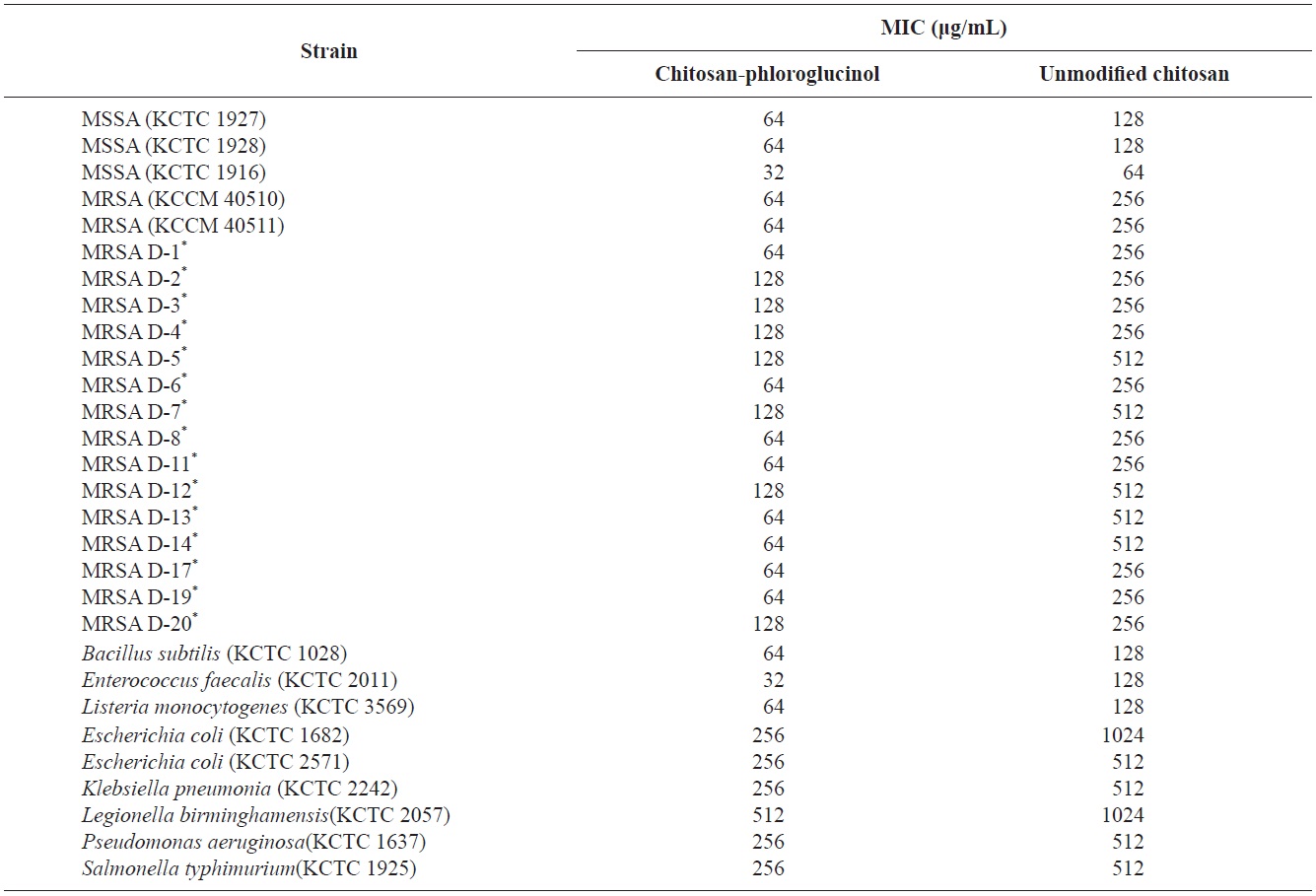

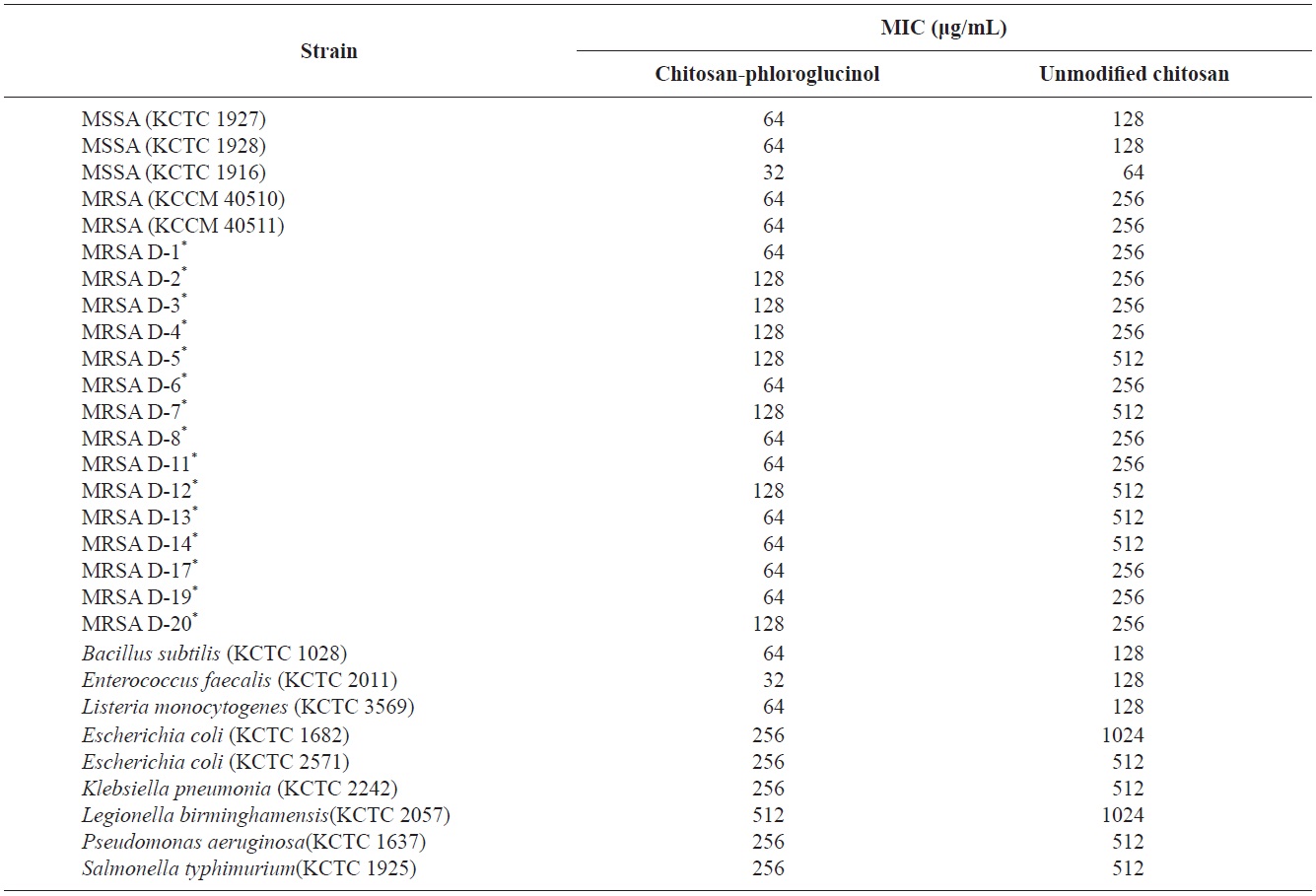

The bacterial strains tested for antibacterial activity were purchased from the Korean Collection for Type Cultures (KCTC; Daejeon, Korea) and 15 clinical isolates of MRSA were provided by Dong-A University Hospital (Busan, Korea). All strains were grown aerobically at 37℃ in Mueller-Hinton broth (Difco, Detroit, MI, USA) and subsequently used for assays of antibacterial activity.

>

Preparation of chitosan-phloroglucinol conjugate

The chitosan-phloroglucinol conjugate was prepared according to our previous method with a slight modification (Woo and Je, 2013). Briefly, chitosan (0.25 g) was dissolved in 25 mL of 2% acetic acid, and then 0.5 mL of 1.0 M hydrogen peroxide containing 0.054 g of ascorbic acid was added. After 30 min, phloroglucinol (18.43 mg) was added to the mixture, and then allowed to rest at room temperature for 24 h. Unreacted phloroglucinol was removed by dialysis for 48 h using distilled water. Unmodified chitosan was also prepared without the addition of phloroglucinol. Molar ratios of repeating units of chitosan to phloroglucinol were 1:0.1, which was optimal.

To confirm successful synthesis, 1H NMR analysis was 230conducted and the results were compared to the report by Woo and Je (2013). Unmodified chitosan: 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O) δ: 4.90 (1H, H-1), 3.14 (1H, H-2), 3.41-4.30 (1H, H-3/6), 2.00 (H-Ac), 5.0 (D2O). Chitosan-phloroglucinol conjugate: 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O) δ: 6.30 and 7.58 (aromatic protons of phloroglucinol), 4.90 (1H, H-1), 3.25 (1H, H-2), 3.65-4.36 (1H, H-3/6), 2.12 (H-Ac), 5.0 (D2O).

The phloroglucinol content of the chitosan-phloroglucinol conjugate determined using the Folin-Ciocalteau method was 29.28 ± 0.90 mg phloroglucinol/g chitosan-phloroglucinol conjugate.

>

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC)

The twofold serial dilution method was used to determine the chitosan-phloroglucinol conjugate MIC against MRSA and foodborne pathogens as described by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (2004). The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration that demonstrated no visible growth after incubation at 37℃ for 24 h.

>

Determination of cellular antioxidant activities

Cell culture. Mouse macrophage cells (RAW264.7) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/mL of penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. The cells were incubated at 37℃ in a humidified atmosphere.

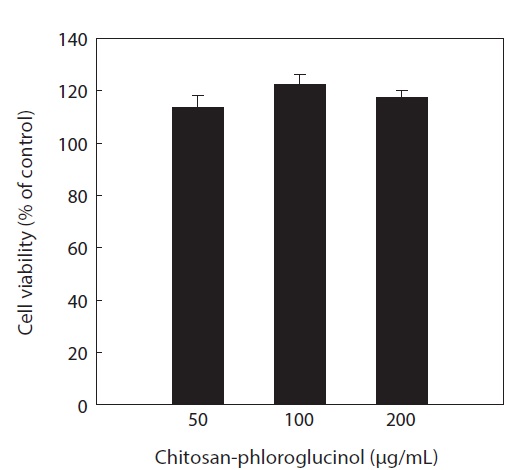

Cytotoxicity assay. Cytotoxicity of the chitosan-phloroglucinol conjugate was estimated using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. RAW264.7 cells were grown in 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well. After 24 h, the cells were treated with the desired concentrations of chitosan-phloroglucinol conjugate and incubated at 37℃ for 24 h. A 100-μL aliquot of MTT solution (1 mg/mL) was added after aspiration of medium and cells were incubated for an additional 4 h. Next, the supernatant was aspirated, and finally, a 100 μL aliquot of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to solubilize the formazan crystals. The quantity of formazan crystals was determined by measuring the absorbance at 540 nm using a microplate reader.

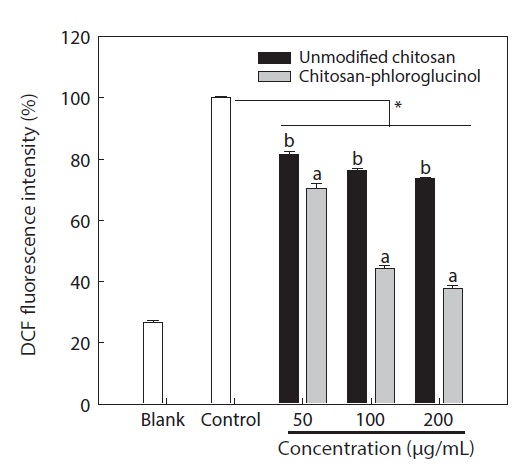

Cellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging activity. Intracellular ROS formation was assessed according to a method described previously, employing the oxidation-sensitive dye DCFH-DA as the substrate (Engelmann et al., 2005). RAW264.7 cells growing in black microtiter 96-well plates were labeled with 20 μM DCFH-DA in HBSS for 20 min in the dark. The cells were then treated with the chitosan-phloroglucinol conjugate and incubated for 1 h. After washing the cells three times with phosphated buffered saline (PBS), 500 μM H2O2 (in HBSS) was added. The formation of 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCF), due to the oxidation of DCFH in the presence of various ROS, was read after every 30 min at an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and an emission wavelength of 528 nm (SpectraMax M2/M2e).

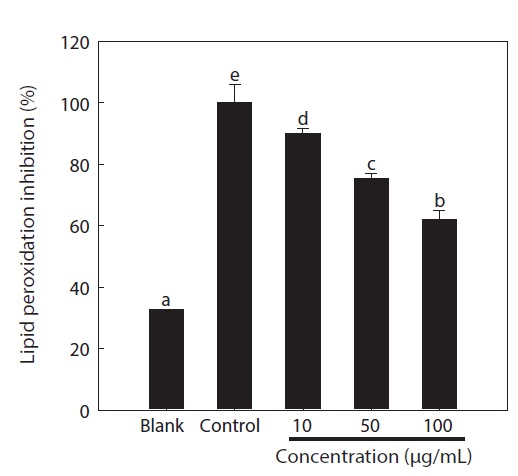

Lipid peroxidation inhibition. Lipid peroxidation inhibition was assessed by measuring the intracellular lipid hydroperoxide level using the fluorescent probe, DPPP (Takahashi et al., 2001). RAW264.7 cells growing in culture dishes were washed three times with PBS and labeled with 13 μM DPPP (dissolved in DMSO) for 30 min at 37℃ in the dark. The cells were then washed three times with PBS and seeded onto fluorescence microtiter 96-well plates at a density of 4 × 105 cells/mL using serum-free media. Following complete attachment, the cells were treated with the chitosan-phloroglucinol conjugate and incubated for 1 h. After incubation, 3 mM AAPH in PBS was added and DPPP oxide fluorescence intensity was measured after 6 h at an excitation wavelength of 361 nm and an emission wavelength of 380 nm. The fluorescence values were normalized to cell numbers using the MTT cell viability assay.

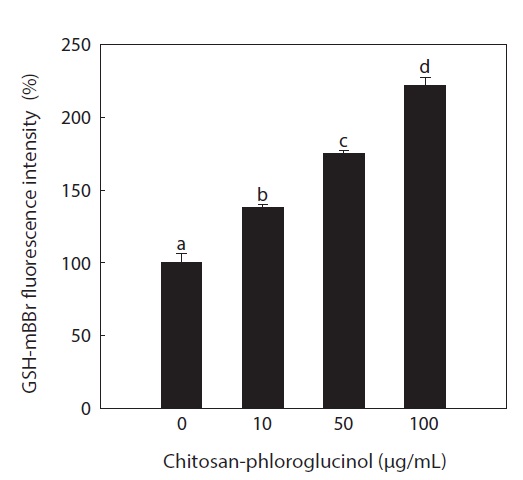

Determination of glutathione (GSH) level. Intracellular GSH level was determined using a thiol-staining reagent, mBBr, according to a previous method with slight modification (Poot et al., 1986). RAW264.7 cells were seeded at a concentration of 4.0 × 105 cells/mL and following confluence, were treated with the chitosan-phloroglucinol conjugate for 1 h. The cells were then labeled with 40 μM mBBr for 30 min, and then mBBr-GSH fluorescence intensity was measured at an excitation wavelength of 360 nm and an emission wavelength of 465 nm using a spectrofluorometer (Spectra Max).

All results are expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD) of three determinations. Differences between the means of each group were assessed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Duncan’s test using the statistical software, PASW Statistics 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A value of

>

Cellular ROS scavenging activity

Cytotoxicity was first determined in RAW264.7 macrophage cells at the desired concentration (50, 100, and 200 μg/ mL) by MTT assay; the results confirmed that the chitosanphloroglucinol conjugate did not exhibit any cytotoxic effect (Fig. 1). Cellular ROS scavenging activities of the chitosanphloroglucinol conjugate and the unmodified chitosan were first evaluated using a fluorescent probe, DCFH-DA (Fig. 2). DCFH-DA freely penetrated into the cells and was hydrolyzed by intracellular esterases to DCFH and trapped inside the cells. DCFH was further oxidized to DCF by ROS, emitting

fluorescence. Pre-treatment with the unmodified chitosan and the chitosan-phloroglucinol conjugate decreased DCF fluorescence in a dose-dependent manner. At 200 μg/mL unmodified chitosan, a 26.29% ROS scavenging activity was observed, whereas the chitosan-phloroglucinol conjugate exhibited 62.29% ROS scavenging activity at the same concentration; this difference was significant (

Excessive production of ROS may lead to a number of de-generative processes, such as cancer, cardiovascular and neurodegenerative conditions, and premature aging (Halliwell and Gutteridge, 1999; Finkel and Holbrook, 2000). Additionally, a crucial step in these ROS-mediated effects is DNA damage (Halliwell and Gutteridge, 1999). Thus, prevention of ROS-induced oxidative stress may help to maintain human health, and consuming dietary antioxidants from natural sources may

have health-promoting effects. In this study, we demonstrated that the chitosan-phloroglucinol conjugate effectively scavenged intracellular ROS.

>

Lipid peroxidation inhibition by the chitosan-phloroglucinol conjugate

Overproduction of ROS results in an attack of not only DNA, but also other cellular components including the polyunsaturated fatty acid residues of phospholipids, which are highly sensitive to oxidation (Siems et al., 1995). Therefore, unsaturated fatty acids in cell membranes are susceptible to free radical-mediated oxidation. The DPPP fluorescent probe was used to evaluate lipid peroxidation in the cells (Fig. 3). After exposure to AAPH, considerable lipid peroxidation was observed in the control group (3.06-fold) compared to the non-treatment group. However, pre-treatment with the chitosan-phloroglucinol conjugate significantly inhibited lipid peroxidation in a dose-dependent manner (

>

Effect of the chitosan-phloroglucinol conjugate on GSH level

GSH is the major soluble antioxidant in cell compartments and is a key cellular reductant, reducing numerous oxidizing compounds, including ROS and lipid peroxides, and is oxidized to GSH disulfide and other mixed disulfides (Kadiska et al., 2000). The main protective roles of GSH against oxidative stress include acting as a cofactor of GSH peroxidase, which detoxifies hydrogen peroxide and lipid peroxides, directly scavenging •OH and singlet oxygen, and regenerating vitamin C and E

>

Antibacterial activity of the chitosan-phloroglucinol conjugate

Chitosan exhibits antibacterial activity against a broad spectrum of foodborne pathogens; this activity is influenced by the type of chitosan, molecular weight and several other physiochemical properties (Park et al., 2004a). To date, many chitosan derivatives exhibiting antibacterial activity have been developed by introducing specific functional groups, indicating that modification of chitosan is a good strategy for developing antibacterial biopolymers (Tang et al., 2010; Xiao et al., 2011). Additionally, we previously demonstrated that gallic acid-

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of chitosan-phloroglucinol and unmodified chitosan

for MSSA and fourfold for standard and clinical MRSA isolates compared to unmodified chitosan. Similar results were observed for foodborne pathogens (Table 1). Unmodified chitosan showed an MIC of 128 μg/mL for gram-positive bacteria (