Like all invertebrates, the fleshy shrimp, Fenneropenaeus chinensis, is protected from pathogens by innate immunity due to the lack of adaptive immunity (Zasloff, 2002). Lysozymes and antibacterial peptides are the first line of defense to protect against bacterial infection in invertebrates, (Jollès and Jollès, 1984). Lysozymes (EC 3.2.1.17) are found within the semi-granular and granular hemocytes of many marine invertebrates and are released by a process of degranulation of hemocytes during the immune response (Ratcliffe et al., 1985; Sung and Sun, 1999). Lysozymes are glycoside hydrolases that catalyze cleavage of the β-1,4-glycosidic bond between N-acetyl glucosamine and N-acetyl muramic acid in the peptidoglycans (PGs) of bacterial cell walls (Qasba and Kumar, 1997). Based on differences in structural, catalytic, and immunological characteristics, lysozymes are generally classified into six main types: chicken-type (Hultmark, 1996), goose-type (Prager and Jollès, 1996), invertebrate (Jollès and Jollès, 1975), T4 phage (Fastrez, 1996), bacterial (Holtje, 1996), and plant (Beintema and Terwisscha van Scheltinga, 1996), whereas immune (i-) and chicken (c-) lysozymes have been found in shrimp (Supungul et al., 2002, 2010). The i-lysozyme was initially described in starfish, Asterias rubens, by Jollès and Jollès (1975).

Subsequently, it has been reported in crustaceans and decapods, which show strong antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (Paskewitz et al., 2008; Supungul et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2010). The i-lysozyme is expressed in multiple tissues and organs, and expression level increases following a bacterial challenge (de-la-Re-Vega et al., 2006; Supungul et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2010). In contrast, i-lysozyme shows high activity in bivalve digestive tissues, and associated species have the ability to use bacteria as a nutrient source (McHenery et al., 1979; Dobson et al., 1984), suggesting that i-lysozyme may function as a digestive enzyme in organisms such as the eastern oyster, Crassostrea virgincia (Xue et al., 2010). Invertebrates may produce different lysozymes for immunity (Peregrino-Uriarte et al., 2012) and digestion (Dobson et al., 1984; Supungul et al., 2010), and the digestive i-lysozyme could have evolved from immune lysozymes via positive selection (Supungul et al., 2010). The c-lysozyme is the most often found group in various organisms, including viruses, bacteria, plants, insects, reptiles, birds, fish, crustaceans, and mammals (Mai and Hu, 2009). In crustaceans, it has been identified in white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei (Sotelo-Mundo et al., 2003), Kuruma prawn, Marsupenaeus japonicus (Hikima et al., 2003), F. chinensis (Bu et al, 2008), giant tiger shrimp, Penaeus monodon (Supungul et al., 2002; Tyagi et al., 2007), banana shrimp, F. merguiensis (Mai and Hu, 2009), swimming crab, Portunus trituberculatus (Pan et al., 2010), and Pacific blue shrimp, L. stylirostris (de Lorgeril et al., 2005; Mai and Hu, 2009). The c-lysozyme from F. chinensis had been cloned and the full-length cDNA sequence (709 bp) has been determined (Bu et al., 2008). An open reading frame of 477 bp is present with 159 encoded amino acids. The predicted protein has a signal peptide, and the theoretical molecular weight of the mature protein is l6.2 kD. The recombinant protein (colonially expressed into Escherichia coli BL2l) shows high antibacterial activity against some Gram-positive bacteria, and has a lower minimal inhibition concentration against Gram-negative bacteria (Bu et al., 2008). However, little information is available on the time-course of the c-lysozyme mRNA transcript level against bacterial infection and tissue-specific expression. Therefore, we designed a real-time probe to detect the tissue-specific distribution to attain a better understanding of c-lysozyme function and its expression level against the pathogen

Vibrio anguillarum. The immunostimulant lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was also investigated to provide new insight into disease control in F. chinensis aquaculture.

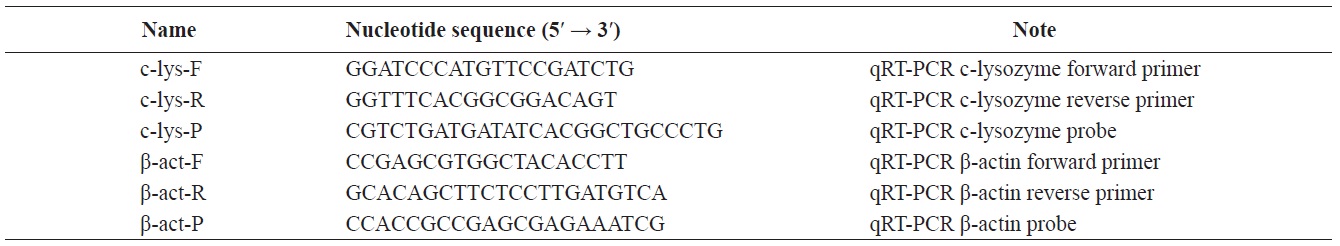

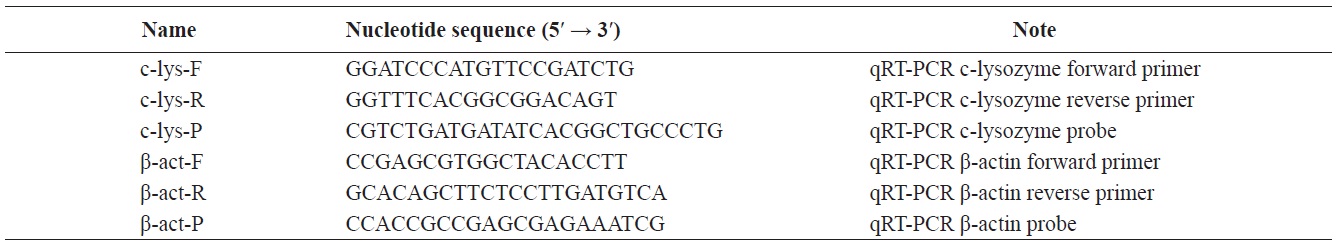

The cDNA sequence (GenBank accession no. AY661543) of the c-lysozyme from F. chinensis was retrieved from the NCBI database. A pair of gene-specific primers c-lyz-F, c-lyz-R and the Taqman probe c-lyz-P were designed from the full-length c-lysozyme cDNA sequence using the PrimerExpress software (Applied Biosystems Pty Ltd., Melbourne, Australia) (Table 1).

Total RNAs from eight tissues, including gill, eyestalk, eye, hemocytes, hepatopancreas, intestine, heart, and pleopod were prepared to determine the c-lysozyme expression sites in F. chinensis, and Taqman probe-based qRT-PCR was carried out to determine the relative transcription levels using the shrimp β-actin gene as an internal control. Seven tissues, except hemocytes, were obtained by dissection and stored in 200 μL of RNA Later reagent (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). Hemocytes were prepared as described by Jang et al. (2011). Briefly, hemolymph was collected from the ventral hemolymph sinus of F. chinensis (average body weight, 2.0 g) with a 1-mL RNase-free syringe containing ice pre-cooled anticoagulant (113 mM glucose, 27.2 mM sodium citrate, 2.8 mM citric acid, and 71.9 mM NaCl). The hemocyte pellet was collected by centrifugation at 700 g and 4℃ for 10 min and diluted with 200 μL of RNA Later reagent. Total RNA was extracted from each tissue using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and further purified with DNase I (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. First-strand cDNA was synthesized with the Prime-script First-strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan) using the oligo dT primer, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The synthesized cDNA was stored at −80℃ for later mRNA expression analysis. The qRT-PCR technique was used to assess the c-lysozyme transcription level using c-lyz-F, c-lyz-R, and Taqman c-lyz-P probe primers (Table 1). The qRT-PCR was conducted using the One-step PrimeScript RT-PCR kit (Takara Bio). The final reaction volume was 20 μL, including 10 μL of 2× One-step RT-PCR Buffer III, 2 units of Takara Ex Hot Start Taq enzyme, 0.4 μL of Reverse Transcript Enzyme Mix II, and 0.4 μM of each primer. The PCR was conducted as follows: 42℃ for 5 min, 95℃ for 10 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95℃ for 5 s and 60℃ for 30 s. Fluorescent signal detection was initiated at the annealing stage during the first cycle. The comparative threshold cycle (CT) method (2−ΔΔCT method) was used to calculate relative expression (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). The relative expression levels among the CT values of the target gene, c-lysozyme, and the β-actin housekeeping gene were compared by the 2−ΔΔCT method.

Shrimp maintenance

Normal F. chinensis (1.2 ± 0.2 g, mean ± standard deviation [SD]) were obtained from the Taean Center at the West Sea Fisheries Research Institute, National Fisheries Research and Development Institute (NFRDI), Korea and maintained in static aquaria at a water temperature of 24-25℃ in 30 practical salinity units at a pH of 7.8-8.2 for 2 weeks prior to the experiments. The shrimp were fed four times daily with a commercial diet (CJ Feeding Co., Seoul, Korea) and 50% of the water was exchanged daily throughout the experimental duration. The feeding ration was 3% of mean body weight per day based on the feed conversion ratio.

V. anguillarum challenge test

V. anguillarum KCTC 2711 was preserved at −80℃ in tryptic soy broth (TSB) supplemented with a final concentration of 2% NaCl and 10% glycerol at NFRDI. The strain was routinely grown in TSB or tryptic soy agar supplemented with 2% NaCl at 27℃ for 24 h prior to experiments. The V. anguillarum challenge tests were conducted in vivo as described by Qiao et al. (2012). In brief, bacterial suspensions were prepared by culturing the strain in TSB at 27℃ for 24 h, followed by washing and then adjusting the concentration to 106 colony-forming units/mL (CFU/mL) with sterilized physiological saline (PS). The shrimp in the challenge groups were injected in the coxes of the third pair of pereiopods with a 0.02-mL suspension of V. anguillarum (106 CFU/mL) using a 0.3-mL insulin syringe (lot, 1234226; Becton Dickinson, Fullerton, CA, USA), and the control group was inoculated with an equal volume of PS. Each group included 70 individuals, and the experiments were conducted in triplicate.

LPS immune stimulation

LPS (integral component of the external membrane of the cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria Escherichia coli serotype O111:B4; Sigma Chemical Co. St. Louis, MO, USA) was stored at 4 ℃, and the working solution (2.4 mg/mL) (Rodríguez-Ramos et al., 2008) was dissolved in sterilized shrimp saline (450 mM NaCl). The challenge tests were conducted as described by Rodríguez-Ramos et al. (2008). Briefly, all shrimp in the stimulation group were injected with 0.02 mL of LPS suspension in the coxes of the third pair of pereiopods using a 100-μL Hamilton syringe containing shrimp saline solution as the diluent. The control group was injected with the same volume of saline solution. Each group included 70 individuals, and the experiments were conducted in triplicate.

Temporal expression of c-lysozyme in response to V. anguillarum and LPS injection

Five individuals were sampled at each time point (0, 1, 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h post injection [hpi]) from the above groups. Total RNA was isolated from the whole body, the cDNA was synthesized, and mRNA expression levels were determined as described above.

Statistical analysis

All samples were run in triplicate, and data are expressed as means ± SD. Significant differences compared to the baseline (time = 0 hpi) of each group were determined by Dunnett’s t-test and significant differences among treatments at each time point were analyzed by Tukey’s range test using the SPSS version 13.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

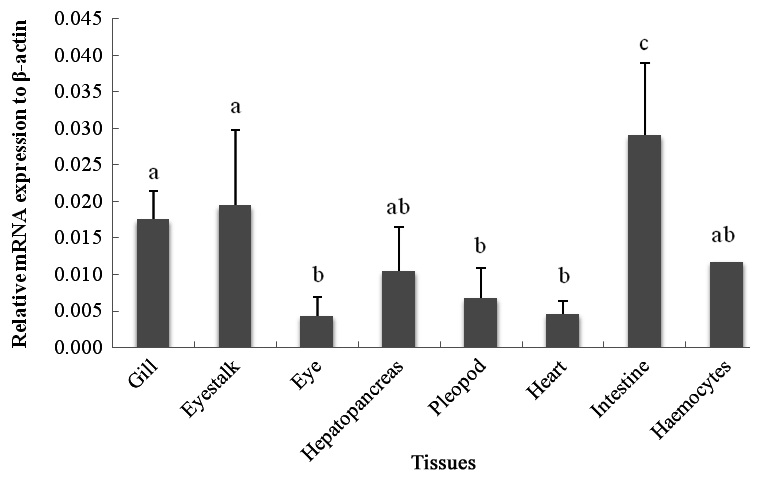

The qRT-PCR results showed that the c-lysozyme transcript was detected in all tissues tested, including gill, eyestalk, eye, hemocytes, hepatopancreas, intestine, heart, and pleopod. It was most highly expressed in the intestine, followed by the eyestalk, gill, hemocytes, and hepatopancreas. The transcript level in the intestine was 1.65-, 1.49-, 2.76-, and 2.46-fold higher than that in the gill, eyestalk, hepatopancreas, and hemocytes, respectively (Fig. 1).

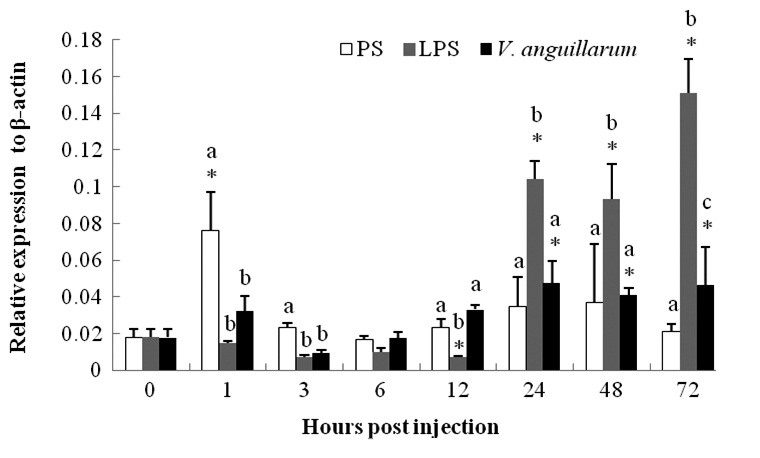

The mRNA expression of c-lysozyme in the entire body of PS-control group shrimp was upregulated 4.25-fold at 1 hpi and then began to recover (Fig. 2). The mRNA level began to decline in a short time post-challenge in the V. anguillarum challenge group and was then upregulated from 24 hpi until the end of the experiment (72 hpi). The transcription level was enhanced by about two fold compared to that at 0 h (Fig. 2).

The c-lysozyme mRNA level was suppressed in a short time after the LPS injection, but began to increase 24 hpi. The expression level was 5.8-, 5.2-, and 8.4-fold at 24, 48, and 72 hpi, respectively, compared with that at 0 h. Higher expression was sustained and showed a gradual increasing trend until the end of the experiment.

The innate immune system represents the first barrier against pathogen infections in fish and shrimp (Zasloff, 2002). The c-lysozyme is an important member of this first line of defense against pathogenic bacteria. This enzyme exhibits lytic activity against a wide range of Gram-positive and -negative bacteria (Paskewitz et al., 2008; Supungul et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2010). Hence, characterizing the c-lysozyme-encoding gene and its regulation by pathogens or immunostimulants is important for improvement of disease management strategies in aquaculture. Bu et al. (2008) cloned c-lysozyme from F. chinensis, and its characteristics were analyzed by bioinformatics. The purified recombinant c-lysozyme shows higher antibacterial activity against Gram-positive bacteria and relatively lower activity against Gram-negative bacteria in vitro, based on the minimum inhibitory concentration (Bu et al., 2008). However, no more information is available on this gene tissue-specific distribution detected by qRT-PCR (probe) and the time-course of gene mRNA expression associated with pathogenic or immunostimulant induction in vivo. Therefore, to further understand the important role of this gene in immunity, we designed a pair of primers and a probe for qRT-PCR to detect mRNA expression in various tissues and under different stimulation conditions. The results demonstrated that the c-lysozyme transcript was detected in all tissues tested, which agreed with the tissue distribution in P. monodon and L. vannamei (Burge et al., 2007; Tyagi et al., 2007; Supungul et al., 2010). c-lysozyme from F. chinensis was most highly expressed in the intestine, followed by the eyestalk, gill, hemocytes, and hepatopancreas, which was different from the patterns in P. monodon, L. vannamei, and L. stylirostris. The c-lysozyme in these species was particularly abundant in hemocytes followed by the intestine (de Lorgeril et al., 2005; Burge et al., 2007; Tyagi et al., 2007; Supungul et al., 2010). This tissue-specific distribution may be related to the species, developmental stage, or size of shrimp used in the various experiments. c-Lysozyme plays a role in the digestive systems of P. monodon, L. vannamei, and L. stylirostris (de Lorgeril et al., 2005; Burge et al., 2007; Tyagi et al., 2007; Supungul et al., 2010) based on its isopeptidase and chitinase activities (McHenery et al., 1979; Dobson et al., 1984; Supungul et al., 2010; Xue et al., 2010). These findings suggest that the high mRNA level in the F. chinensis intestine may be related to digestive function.

V. anguillarum is a prevalent pathogenic bacterium that affects commercial F. chinensis production (Yao et al., 2008). Unlike V. harveyi, little information is available on the immune response of shrimp against V. anguillarum infection. Therefore, we investigated the time-course c-lysozyme mRNA level to evaluate the effects of V. anguillarum and LPS on shrimp immunity. The c-lysozyme mRNA level in shrimp infected with V. anguillarum was downregulated for a short time and then upregulated at 24 h after V. anguillarum injection. Yao et al. (2008) investigated the lysozyme-like activity in F. chinensis after injection with V. anguillarum, and found that the activity increased significantly in hemocytes, which agreed with the results of several studies of lysozyme-like activity in shrimp (Burge et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2007). However, those studies lacked detailed information about lysozyme types and the related mRNA levels associated with lysozyme-like activity. In other words, it is difficult to say which lysozyme genes modulate this lysozyme-like activity due to the various types of lysozymes. Upregulation of c-lysozyme mRNA expression at 24 hpi was in agreement with results reported for L. vannamei whose c-lysozyme has antibacterial activity against V. alginolyticus, V. parahaemolyticus, and V. cholerae (de-la-Re-Vega et al., 2006). Similar results were reported in the swamp crayfish, P. clarkii (Zhang et al., 2010), and in P. monodon hemocytes after 6, 12, and 24 hpi as a response to bacterial challenge (Supungul et al., 2010). These results suggest that the c-lysozyme from F. chinensis is involved in the innate immune system as well as in the digestive system.

The time-course of the mRNA level after V. anguillarum infection demonstrated that c-lysozyme has antibacterial activity. The biochemical mechanism of this activity is elusive, as it is possible that shrimp c-lysozyme enzymatically attacks LPS or the enzyme may be located in the periplasmic space where it can degrade PG, its natural substrate (de-la-Re-Vega et al., 2006). Gram-negative bacteria such as Vibrio sp. contain LPS in the cell wall and PGs in the periplasmic space (Peregrino-Uriarte et al., 2012). Therefore, the c-lysozyme mRNA level was investigated after LPS injection. The results showed that c-lysozyme expression levels decreased by 0.3-fold at 3 hpi, then increased by 8- and 21-fold at 72 hpi compared to at 0 and 3 hpi, respectively. These changes are in agreement with the results observed in the fat body of the army worm, Spodoptera exigua, after LPS injection (Bae and Kim, 2003). This result is also in accordance with reports of moderately increased lysozyme-like activity in the hemocytes of F. chinensis after laminarin injection (Yao et al., 2008). Similarly, the expression of c-lysozyme increases in P. monodon and L. vannamei after laminarin, LPS, and poly I: C stimulation (Ji et al., 2009; Peregrino-Uriarte et al., 2012). These results suggest that c-lysozyme expression level in F. chinensis was enhanced after LPS stimulation. These findings will facilitate the development of effective approaches for disease prevention, such as use of immunostimulants, including LPS. Moreover, further studies of i-lysozyme from F. chinensis are required to elucidate its mechanism of action. The type of lysozyme (c- or i-lysozyme) that plays the more important role in the immune response and digestive system will be elucidated in future studies.