Tc-99m is the most widely used radiopharmaceutical isotope for medical diagnostic purposes [1]. The key source for Tc-99m generation is Mo-99, produced from the nuclear fission of uranium in research reactors. Approximately 6.1% of U-235 fissions produce Mo-99; Tc-99m is obtained from the radioactive decay of Mo-99 with a half-life of about 66 hours. Major producers of Mo-99 still use U-Al alloy targets containing highly enriched uranium (HEU) [2]. However, international non-proliferation policies have emphasized that the use of HEU should be eliminated in medical radioisotope production [3]. Therefore, researchers have pursued the development of low-enriched uranium (LEU) targets. One example is the casting and crushing of UAl2 compounds [4]. UAl2 particle dispersed targets have lower U-235 density than HEU targets. The uranium density of the conventional UAl2 dispersion targets is known to be lower than 2.7 g·U/cm3. After irradiation in a research reactor for several days at a neutron flux of about 1014 n/cm2·s, the irradiated UAlx/Al dispersion targets are dissolved in pure alkaline or NaOH/NaNO3 solution to extract Mo-99 [5]. The alkaline dissolution of the irradiated targets has more advantages than an acid dissolution process. One advantage is that all of the uranium in the targets can be filtered out as N2U2O7 powder after alkaline dissolution [6]. Management of solid LEU waste is easier than the liquid form considering the nuclear criticality control. However, metallic uranium does not dissolve in alkaline solutions. Therefore, research on metallic uranium targets tends to focus on the development of acid dissolution or electrolytic dissolution in a carbonate solution [7].

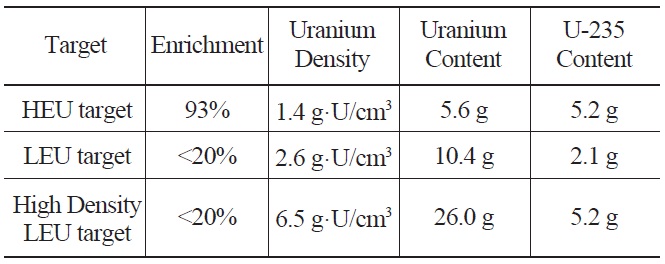

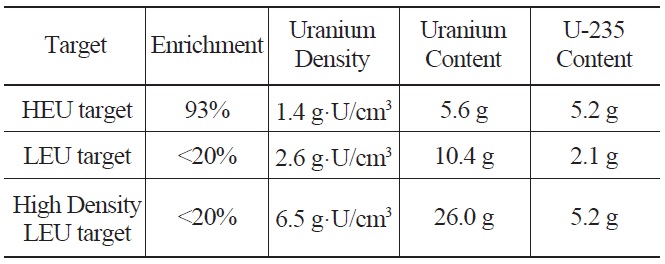

Table 1 compares the U-235 content of HEU and LEU target plates with a meat volume of 4 cm3. HEU U-Al targets with 1.4 g·U/cm3 have a U-235 density 2.5 times higher

Comparison of Uranium Densities and U-235 Content in a HEU Target, a Conventional LEU Target and a High Density LEU Target with a Meat Volume of 4 cm3.

than that of LEU UAl2 dispersion targets. If the uranium density of the LEU target is increased up to 6.5 g·U/cm3, the U-235 content becomes similar in LEU and HEU targets. However, because of the presence of U-238, the production yield of LEU targets will be slightly lower than that of HEU targets with the same U-235 content [8].

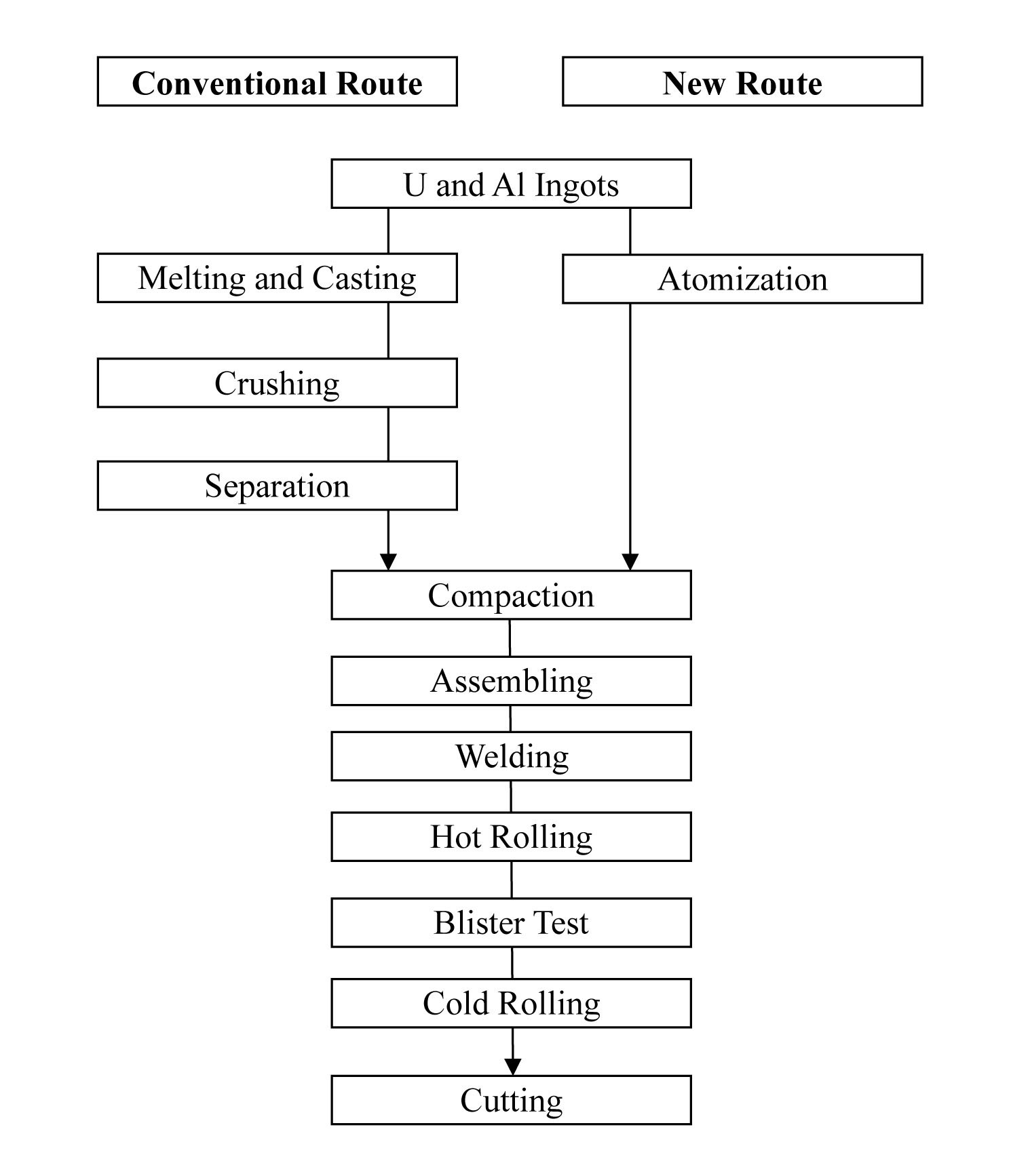

To improve the Mo-99 production efficiency, researchers have tried to develop high-uranium-density targets with LEU materials [9]. It has been proposed that high density uranium alloys, instead of UAl2, can be used as dispersing particles in an aluminum matrix [10]. While it is difficult and time-consuming to fabricate uranium alloy powders by grinding or crushing, a spherical powder of uranium alloys can be easily produced by centrifugal atomization. Fig. 1 shows a flow chart for the fabrication of dispersion targets [11,12]. In the conventional route, uranium and aluminum ingots are melted and casted to produce a UAl2 ingot. The UAl2 ingot is crushed to powder to be compacted with additional aluminum powder. If atomized powder technology is used, the fabrication of dispersion targets can be significantly simplified.

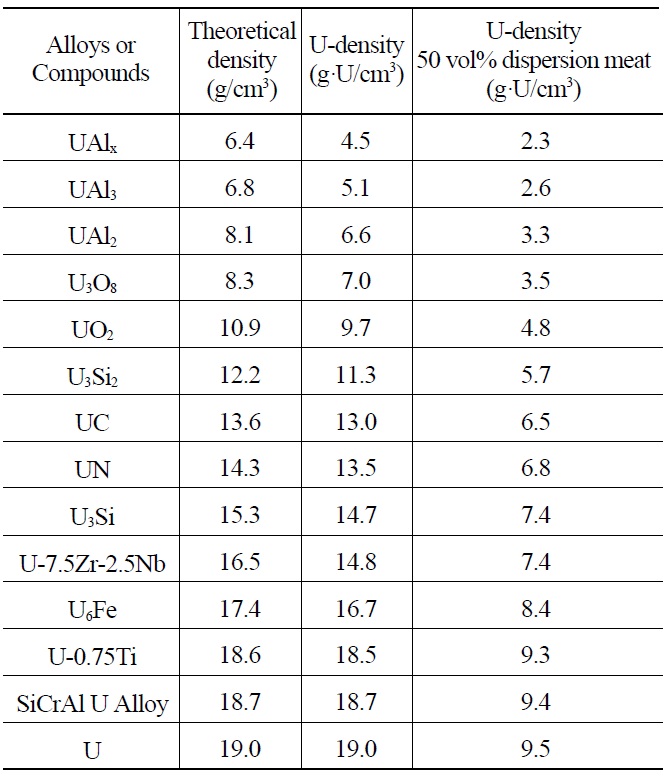

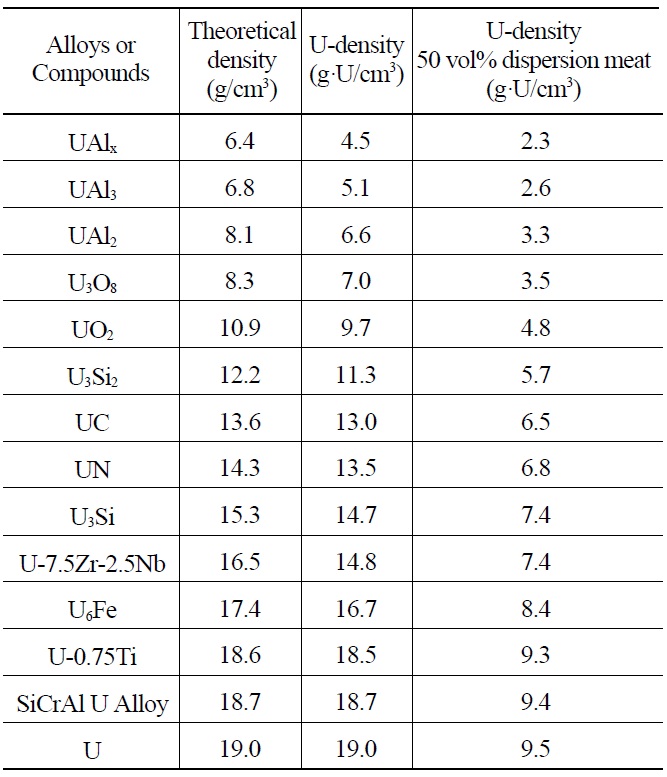

Many uranium alloys and compounds are potential candidates for use as dispersion targets for Mo-99 production. Table 2 lists candidate alloys and compounds ranging from UAlx to pure uranium. UAlx refers to a mixture of uranium aluminides resulting from melting and casting

Theoretical Densities and Uranium Densities of Candidate Uranium Alloys and Compounds Sorted by Density.

of a uranium-aluminum binary system. HEU dispersion targets fabricated by the casting of U-Al alloys contain UAlx particles in the Al matrix. Generally, UAlx consists mainly of UAl3 and UAl4. A particle loading of 50 vol.% is considered to be the practical limit for dispersion of meats fabricated by roll bonding. Depending on the type of alloys and compounds used in the meat, the uranium density of dispersion target plates can vary theoretically from 2.3 to 9.5 g·U/cm3.

In this study, fabrication of high density dispersion targets using atomized uranium powder is investigated. The changes in the microstructure of the target plates after hot rolling and additional heat treatment are studied to analyze the interaction between the uranium particles and the aluminum matrix.

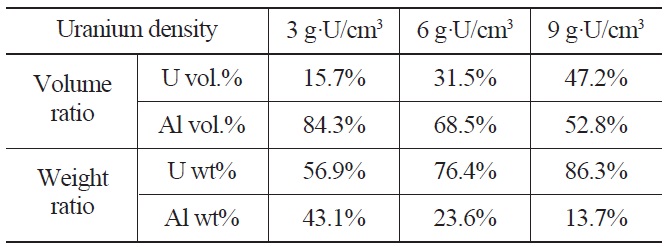

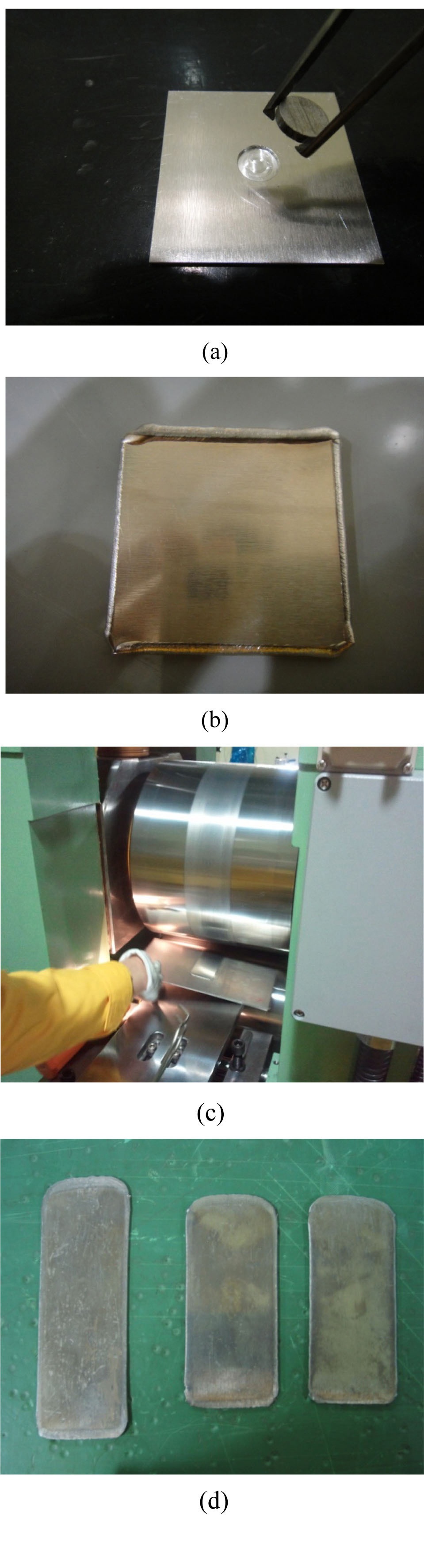

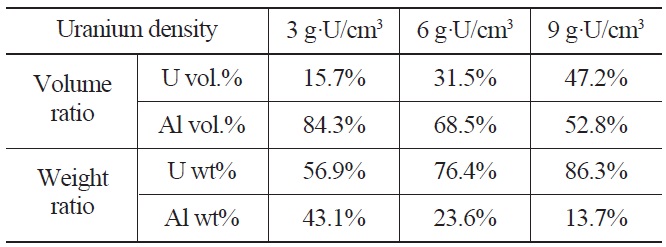

Pure uranium powder and U-1wt%Al powder were fabricated by centrifugal atomization at the Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute. Detailed parameters for the centrifugal atomization are described elsewhere [13]. The target alloys are superheated by induction to ~300 ℃ above their melting point to increase the flowability of the melt, which is then poured into a spinning disk operating at>20,000 rpm. A powder of spherical U particles is obtained with a typical diameter of 70 µm. The atomized spherical uranium powder and pure aluminum powder were mixed and compacted to form dispersion targets with uranium densities of 3, 6, and 9 g-U/cm3. The calculated volume fractions and weight fractions of uranium dispersion targets with uranium densities ranging from 3 to 9 g⋅U/cm3 are given in Table 3. The mixed powder compacts, 10 mm in diameter and 2 mm in thickness, were sandwiched between two 1 mm thick 6061Al cover plates. The cover plates were welded by an electron beam under a vacuum. The obtained welded plates were initially 4 mm in thickness and hot rolled at 500 ℃ to thickness of 1.5 mm by three rolling passes. Blister tests were conducted at 485 ℃ for 1 hour to check the bonding integrity of the dispersion target plates. Key steps for the fabrication of mini-size target plates are shown in Fig. 2. The cross-sectional microstructure of the fabricated targets was observed by scanning electron microscopy. The targets were subjected

Volume and Weight Fractions of Uranium Dispersion Targets with Uranium Density of 3, 6, and 9 g·U/ cm3.

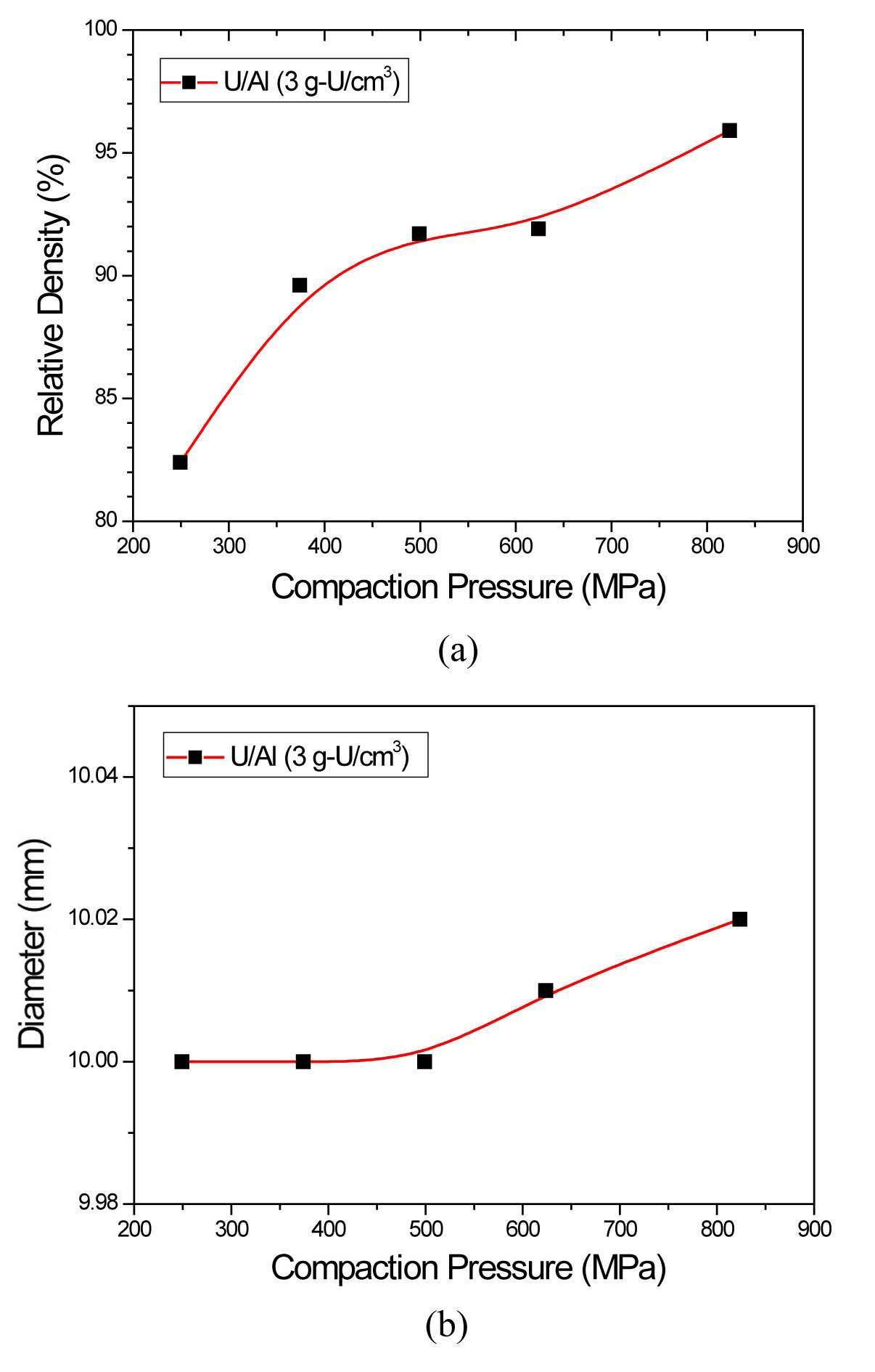

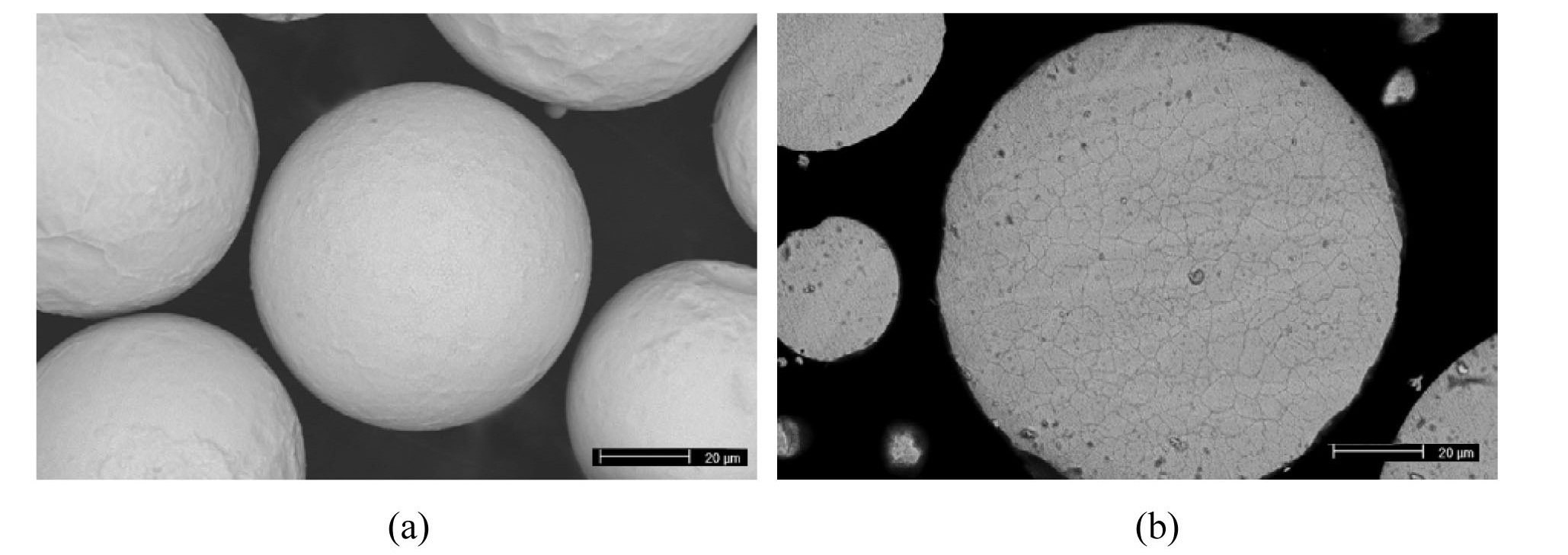

The particles of metallic uranium powder fabricated by centrifugal atomization are spherical (Fig. 3). The average diameter of the powder particles was about 70 µm. Compaction behavior was evaluated by measuring the green densities and radial springback of U/Al compacts. Green density is a relative density of an unsintered compact and springback is the slight increase in compact size after the compact is removed from the die. Compaction pressure is the main parameter controlling the green properties of U/Al compacts. The relative density of U/Al mixed powder compacts increases up to 95% with compaction pressure from 250 MPa to 800 MPa and the radial springback also increases up to 0.2% with compaction pressure as shown in Fig. 4. The springback should be measured to design the compaction die cavity and Al sandwich frames because the final width of dispersion meat is determined by the initial compact width.

A higher relative green density of compacts means a lower porosity, and therefore, a denser fuel meat can be fabricated using such compacts. However, no specified value recommended has been defined for the relative green density of the compacts, because the density might further increase during the hot rolling of the compacts. An advantage of using atomized powder over ground powder is the higher relative density, i.e., lower porosity, attainable in the compacts. This is because the spherical shape of atomized powder particles facilitates the compaction and rolling of the mixed powders.

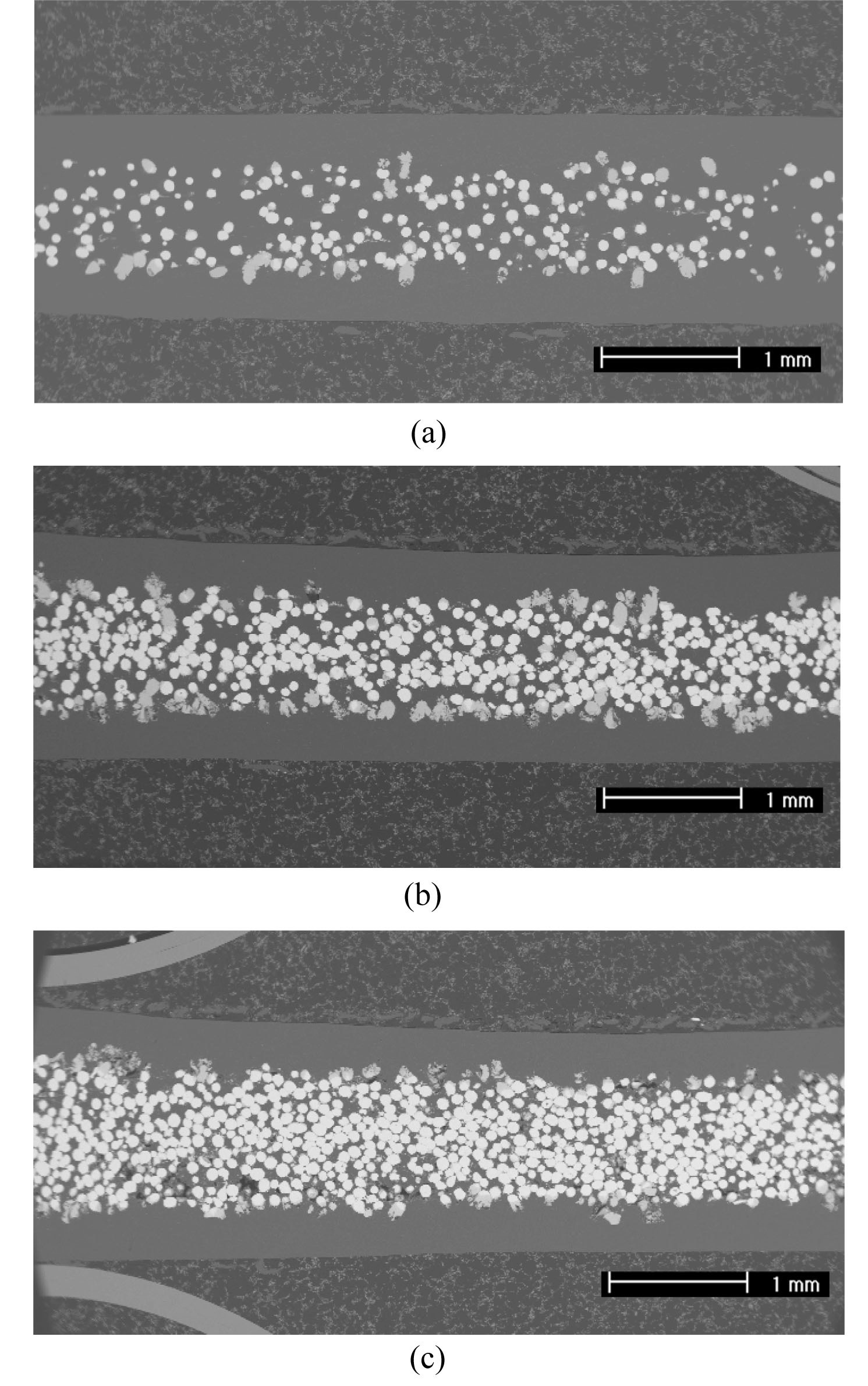

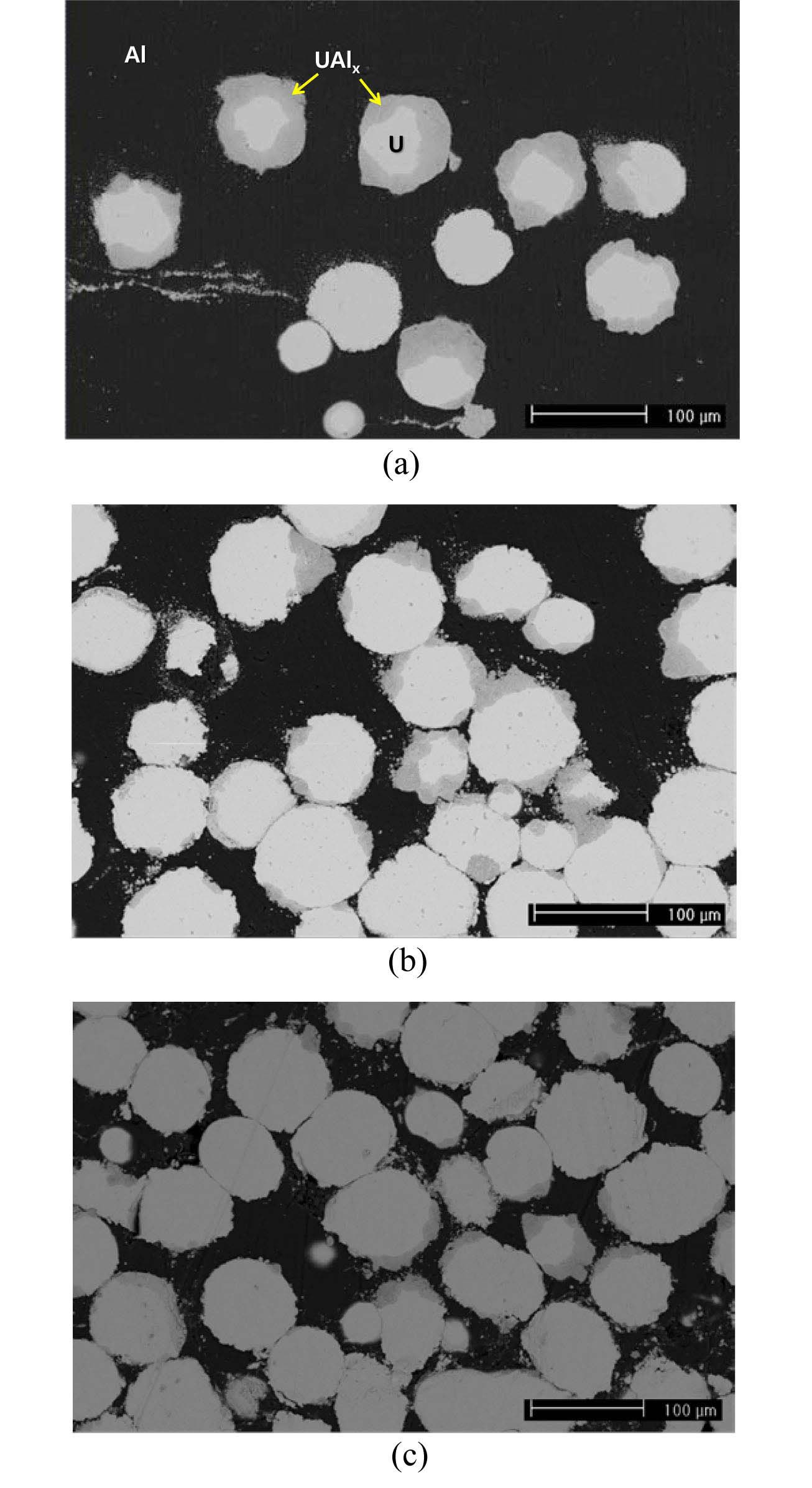

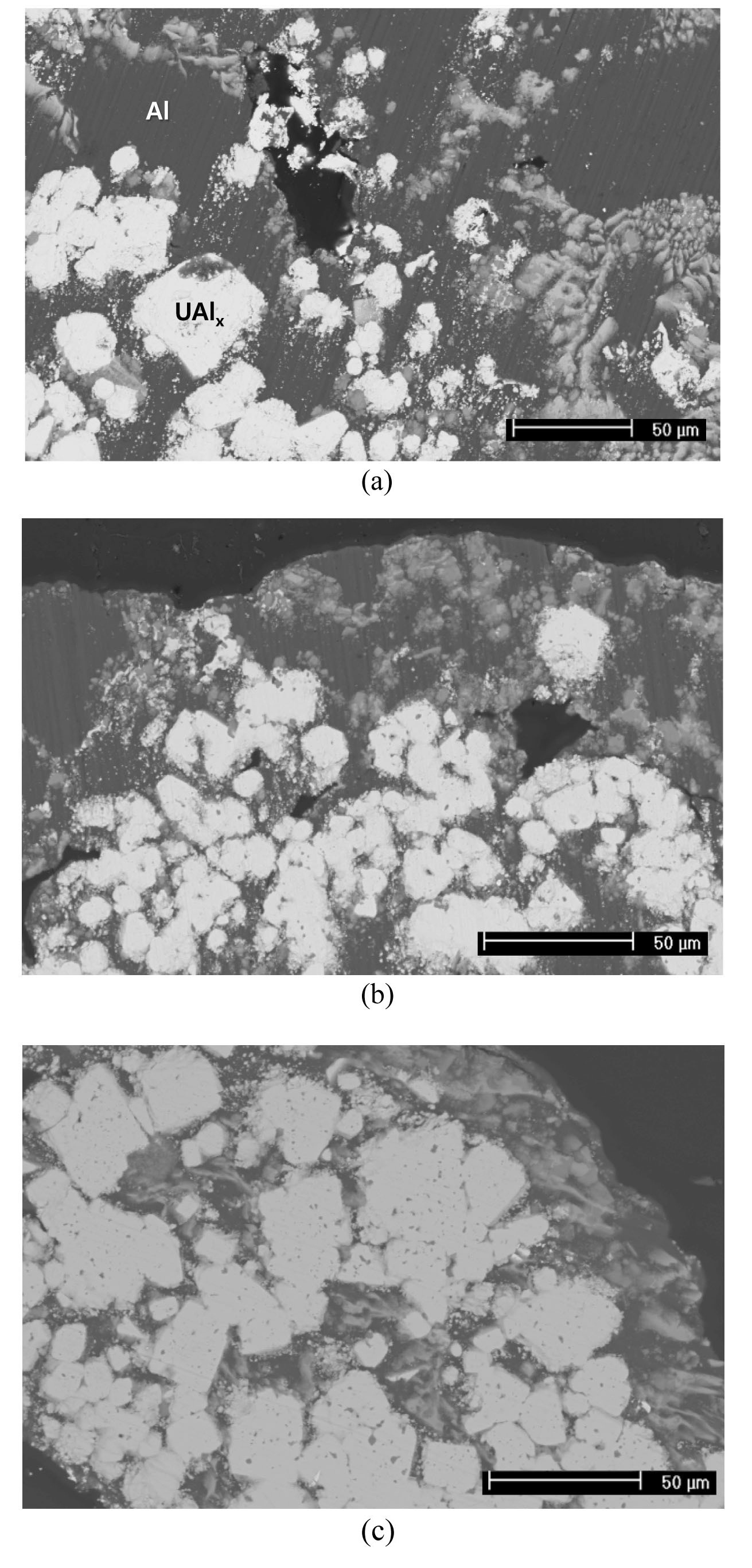

Fig. 5 shows the fabrication of U/Al dispersion targets with uranium densities of 3, 6, and 9 g⋅U/cm3. Micrographs of the cross-sections after hot rolling showed that uranium powder is well distributed between the aluminum cladding. Fig. 6 shows that the interaction layers were formed by a chemical reaction between uranium and aluminum. The composition of the interaction layers was similar to UAl3. During annealing at 500 ℃ before and after hot rolling, the uranium particles and the aluminum matrix chemically react in U/Al dispersion target samples. The resulting change in the volume can be calculated using the volume fraction

and theoretical densities of U, Al, and UAl3,

where Xv is the volume change after a reaction, W is the molecular mass, and r is the theoretical density. Theoretical densities of U and UAl3 are given in Table 2. According to Equation 1, a volume increase of about 10% is expected when U and Al form UAl3.

The fabrication processes for U/Al dispersion target plates are not much different from those for plate-type research reactor fuels such as UAlx/Al, U3O8/Al, and U3Si2 /Al dispersion fuels. Accordingly, there have been attempts to develop high density targets by using the conventional U3Si2/Al dispersion fuel fabrication technology [14]. One of the unique contributions of this study different from conventional fabrication processes is the use of atomized uranium metal powder for the realization of dispersion target plates with the high uranium density up to 9 g-U/cm3.

From the experience of irradiation tests of dispersion fuels, there are several issues regarding the irradiation performance of metallic uranium. Therefore, it is necessary to analyze irradiation performance issues related to metal uranium or uranium alloys in order to assure the feasibility of the high density dispersion target plates using uranium metal powder.

Chemical interaction between the uranium particles and Al matrix, and irradiation swelling of the metallic uranium, are among the performance issues associated with using uranium particles instead of using UAlx. However, it is expected that the problem of interaction and swelling of the dispersion targets will not be critical as research reactor fuels, because the in-reactor duration of the dispersion targets will be only around one week, which is much shorter than that of the driver fuel, whose life cycle length ranges from several months to years. Furthermore the burnup in the atomized dispersion targets will be only about 1 %.

Similar challenges exist in the development of high density U-Mo dispersion fuel for research reactors. Chemical interaction between uranium and aluminum is a common issue in U-Mo/Al dispersion fuels and U/Al dispersion targets [15]. Several remedies have been proposed to solve this problem. One way to reduce the chemical interaction between uranium and aluminum is adding a small amount of Si into the Al matrix [16]. Because Si preferentially reacts with uranium and forms a stable interaction layer, chemical interaction between uranium and aluminum can

be significantly retarded. Another way to prevent the uranium alloy particles from interacting with aluminum is to coat the surface of the uranium alloy particles with protective layers [17]. Nitrides and silicides have been applied to coat U-Mo particles to reduce the chemical interaction during irradiation of U-Mo/Al dispersion fuel [18]. Using uranium alloy particles with a larger size can be another solution to reduce the total volume fraction of the interaction layers [19]. However, it is necessary to check that the addition of Si or N does not disturb the Mo-99 extraction process.

Irradiation growth of the metallic uranium is known to be associated with the presence of anisotropic alpha-phase uranium [20]. Beta-phase quenching is used to refine the microstructure of metallic uranium and reduce the volume fraction of the anisotropic alpha phase [21]. Because atomized powder has a fine grain structure owing to a rapid solidification from the melt, its anisotropic irradiation growth will be minimized. A small amount of additives can also stabilize the metallic uranium against the irradiation swelling [22]. Aluminum, iron, and silicon were used as minor alloying elements for stabilizing the metallic uranium

fuel for MAGNOX reactors and French NUGG (Natural Uranium Graphite Gas) reactors. The minor alloying elements result in grain size refinement, fine precipitates, and the absence of a preferred orientation. Again, it is necessary to check the potential chemical interference between the additives and the Mo-99 extraction process during the alloy design of uranium alloys for dispersion targets.

Fabrication of the atomized uranium powder containing a minor alloying element has been demonstrated in this study. To investigate the effect of a minor element addition, U-1wt%Al was fabricated by the centrifugal atomization technique. Almost the same atomization parameters were adopted for the atomization of the U-1wt%Al powder. Fig. 7 shows the spherical morphology of the atomized U-1wt%Al particles and a cross-section micrograph where the fine grain structures are evident. The average grain size in a particle was measured about 5 µm. Precipitation of UAl2 is expected because the maximum solubility of aluminum in U-Al mixtures is 0.7 wt% according to the U-Al phase diagram. However, because the volume fraction of UAl2 is quite small, UAl2 precipitates were not observed in the micrographs.

In spite of the highest uranium density of uranium metal dispersion targets, expected changes in the subsequent dissolution and extraction processes will significantly limit the applicability of the targets. In order to develop useful high density target systems enabling the Mo-99 production facilities to maintain the conventional chemical processes, conversion of metallic uranium into uranium aluminide by an additional heat treatment are proposed in this study.

U/Al dispersion targets were heat treated to form uranium aluminides by the thermal reaction of uranium and aluminum [23]. Because Ryu et al. reported that an exothermic reaction occurs after 65 ℃ for U-Mo/Al dispersion fuel samples [15], the heat treatment temperature was set to 700 ℃.

The heat treatment process for the chemical reaction between U and Al at 700 ℃ is intended to be performed after irradiation in a gas-tight vessel, because the Al cladding of the target plates deform severely due to the melting during the heat treatment. Heat treatment before irradiation should

be performed at a temperature less than the solidus temperature of Al 6061, i.e. 582 ℃.

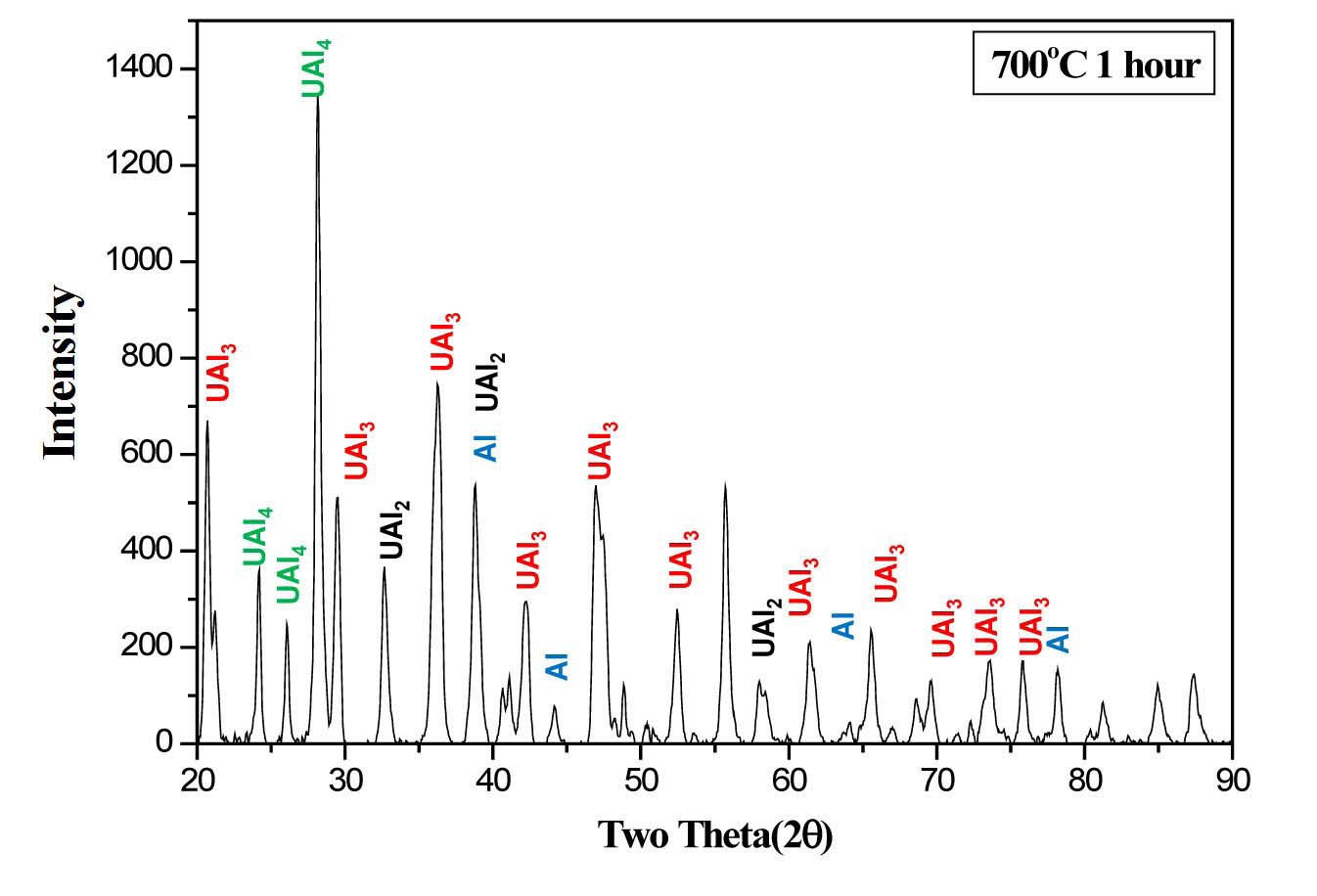

Microstructural analyses show that uranium reacts completely with aluminum as shown in Fig. 8. The Al composition of the reaction product ranging from 77 to

86at.%. UAl2, UAl3, and UAl4 phases were identified by X-ray diffraction analysis of the heat treated dispersion samples, as shown in Fig. 9. This study confirmed that U/Al dispersion targets can be compatible with the conventional alkaline dissolution process when all the metallic uranium is converted into uranium aluminides. The heat treatments for converting uranium into uranium aluminides can be applied to the irradiated targets in a sealed vessel connected with a filter to trap gaseous fission products released during the heat treatment.

It was demonstrated that high density dispersion target plates for Mo-99 production can be fabricated using atomized uranium particles. U/Al dispersion target plate samples with uranium density of up to 9 g·U/cm3 were fabricated by hot rolling of U/Al mixed powder compacts at 500 ℃. Spherical uranium alloy powder with 1 wt% Al was fabricated by centrifugal atomization under the same atomization conditions as for pure uranium powder. Uranium particles were converted into UAlx, which is compatible with the alkaline dissolution, by the additional heat treatment of dispersion target plates at 700 ℃ for 1 hour.