It has been previously reported that regenerated silk fibroin (SF) is highly compatible with blood (Sakabe

Several studies have been conducted on the wet spinning of silk, and many researchers have tried to find a new and effective solvent/coagulant system to fabricate regenerated silk fibers with desirable mechanical properties (Trabbic and Yager, 1998; Liivak

Cellulose nanofibrils (CNFs) are typically obtained from cellulose by various means, including chemical and physical treatments (Klemm

Recently, in relation to regenerated silk, the preparation of the nanocomposite material using nanosized cellulose has been studied by a plethora of researchers. Huang

Although several researchers have reported nanocellulose-based silk composite films and electrospun fibers, an experiment concerning wet-spun nanocellulose/SF composites has not been performed until now. In this study, CNFs were added to SF to prepare CNF/SF fibers using a wet-spinning technique, and the effect of the CNF content on the rheological properties, wet-spinnability, molecular conformation of the fiber, and fiber morphology was examined.

CNFs were isolated from cellulose pulp according to the modified TEMPO oxidation method (Saito et al. 2004). In short, the kraft pulp sample (2 g of cellulose) was suspended in water (150 mL) containing TEMPO (0.025 g) and sodium bromide (0.25 g). The TEMPO-mediated oxidation of the cellulose slurry was initiated by adding 5 mmol of 13% NaClO for every gram of cellulose and carried out at room temperature under gentle agitation. The pH was maintained at 10.5 by adding 0.5 M NaOH. When a decrease in pH was no longer observed, the reaction was considered complete, and the pH was then adjusted to 7 by adding 0.5 M HCl. The TEMPO-oxidized product was filtered, thoroughly washed with water, and physically fibrillated by ultrasonication in a sonicator (Sonosmasher, Jeio Tech, Korea) for 20 minute. The suspension was then centrifuged at 5000 rpm two or three times for 30 minute. The supernatant, which was in fact a suspension containing the CNFs, was decanted and collected. The yield of the CNFs was calculated as a percentage of the initial weight of the CNF suspension after drying in an oven at 105℃. The final concentration of the CNFs was adjusted to 0.1% by weight/volume.

>

Preparation of regenerated SF

The method for preparing the regenerated SF was introduced in a previous study (Yoo

>

Preparation of CNF/SF composite fibers

A 5% (w/w) regenerated SF formic acid solution was prepared by dissolving the regenerated SF in 98% formic acid. Approximately 1?5 wt% (against the dry mass of regenerated SF) of CNFs was added to the 5% SF formic acid solution to prepare CNF/SF dope solutions. Prior to wet spinning, the CNF/SF dope solutions were filtered twice through nonwoven fabric to remove any insoluble particles. The CNF/SF composite fibers were spun using a syringe and syringe pump by extruding the dope solution through a 26-gauge needle (inner diameter=0.241, with a needle length of 0.5 inch) into methanol, which acts as a coagulation bath. The flow rate of the fiber extrusion was controlled at 20 mL/h. The as-spun SF filaments were left to stand in the coagulant overnight to allow the solvent (formic acid) to diffuse out completely from the filament prior to post-drawing and drying.

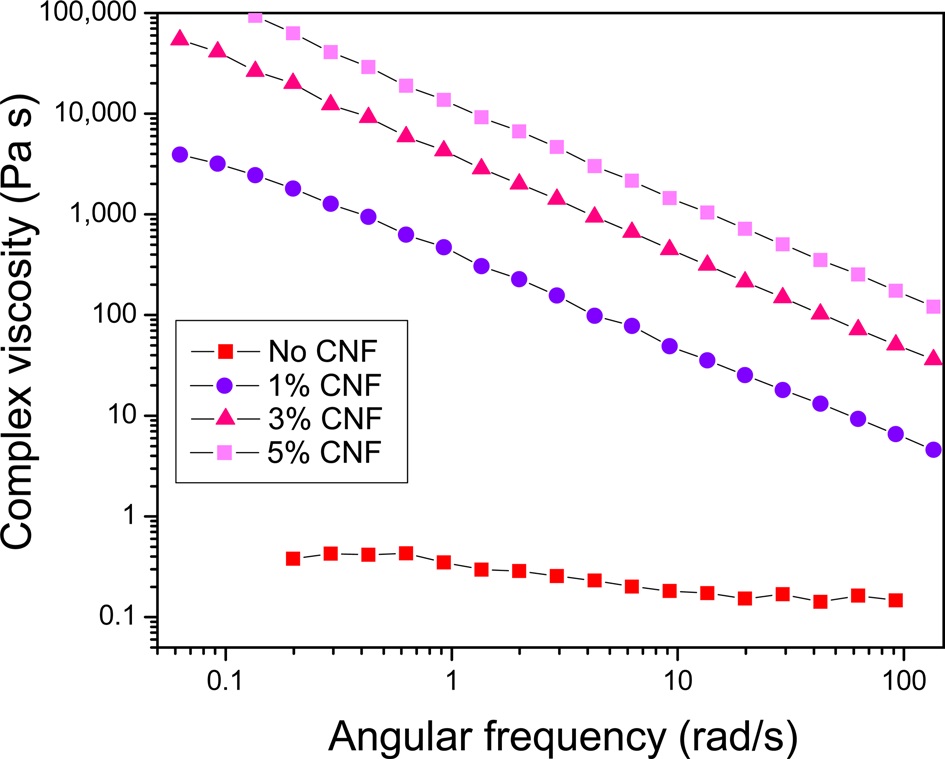

The CNF/SF dope solutions for wet spinning were used for the rheological measurements. The complex viscosity of the solutions was measured by rheometry (MARS III, Hakke, Germany), using a cone and plate geometry at 25℃. An oscillation test was performed with a strain of 0.01%. The radius and angle of the cone were 60 mm and 1°, respectively.

>

Maximum draw ratio measurement

The maximum draw ratio was calculated from the ratio of the maximum drawn length of the fiber and the length of the as-spun fiber in the wet state. The fiber length measurements were performed on 20 different parts of the filament, and the maximum draw ratio was determined by averaging the 20 results (Cho

>

FTIR measurement and determination of crystallinity index

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) (Nicolet 380, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) spectra were obtained using the ATR method. The crystallinity index was calculated as the intensity ratio of the peaks at 1260 cm-1 and 1235 cm-1 from the FTIR spectrum, using the following equation (Bhat and Nadiger, 1980):

A1235cm-1 : Absorbance at 1235 cm-1

A1260cm-1 : Absorbance at 1260 cm-1

To obtain the average and variation of the crystallinity index, FTIR measurements were performed on five different portions of the samples.

The morphology of the CNF/SF composite fibers was observed by field-emission SEM observation (FE-SEM, S-4300, Hitachi, Japan) after coating them with gold.

>

Rheological properties and wet spinnability of dope solution

The rheological properties of the dope solution were examined since they strongly affect the fiber formation performance when using wet-spinning or electrospinning techniques (Cho

To understand the change in the rheological properties of the regenerated silk/formic acid solution after adding the CNFs, the complex viscosity of the dope solution was measured; the results are shown in (Fig. 1). The 5% regenerated SF solution without CNFs showed almost Newtonian fluid behavior, although slight shear thinning was observed. This is consistent with the shear viscosity

results of SF formic acid solutions (Ko

>

Post-drawing performance of wet-spun filament

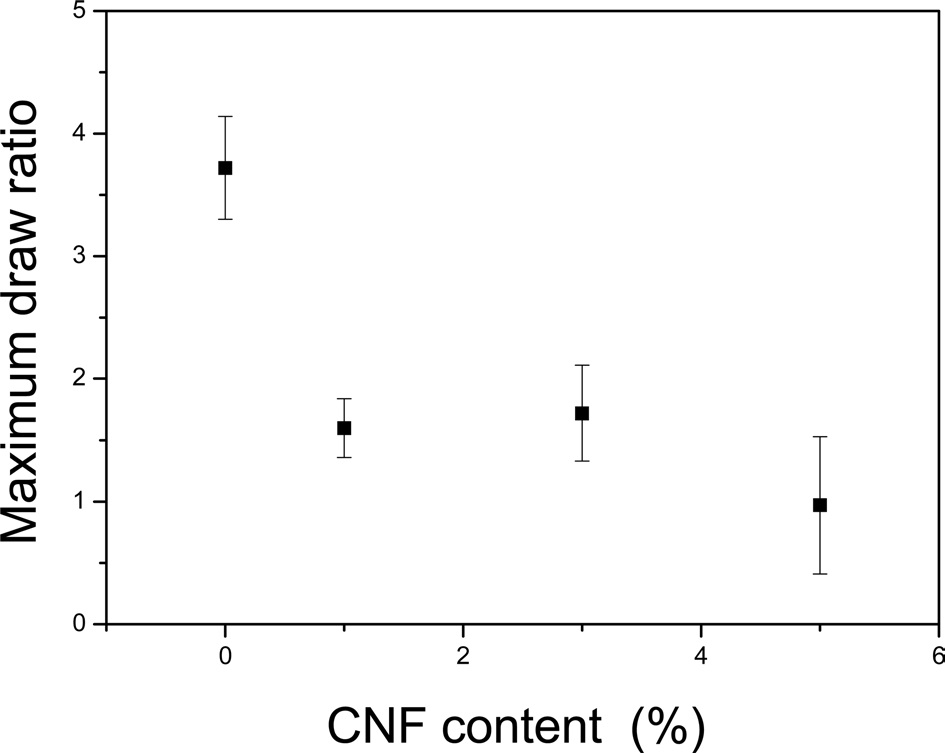

Fiber orientation is a very important characteristic since it determines the mechanical properties of the fiber. In particular, the breaking strength of the fiber tends to be higher as the fiber orientation of wet-spun filaments increases. Um

fiber (Yoo

(Fig. 2) shows the maximum draw ratio of CNF/regenerated silk filaments with different CNF contents. Without CNFs, the regenerated silk filament showed a maximum draw ratio of 3.7. However, as more CNFs were added to the silk, the maximum draw ratio decreased. This result indicated that the post drawing ability deteriorates with increasing CNF content, probably because of the inhomogeneous dope solution. Thus, the regenerated silk solution without CNFs is homogeneous and transparent. However, as the CNFs are added to the silk solution, the dope solution becomes turbid, with a higher degree of CNF and silk aggregation. In other words, the dope solution becomes inhomogeneous upon the addition of CNFs, and this solution with cellulose aggregates can prevent homogenous fiber spinning, resulting in beads and beaded fibers. The beads and beaded fibers can subsequently restrict post-drawing of the as-spun CNF/silk fibers, resulting in a decrease in the maximum draw ratio.

>

Molecular conformation of wet-spun filaments

The molecular conformation of the silk was examined since it strongly affects the chemical and physical properties of the silk polymers. β-sheet conformations help in the formation of crystalline regions of the silk, whereas random-coil conformations contribute to the formation of the amorphous region. Therefore, when the amount of

β-sheets increases, the silk fiber becomes stronger, less water-soluble, and less degradable. FTIR analysis was used to examine the molecular conformation of the silk since different conformations yield absorption peaks at different positions in Amides I, II, and III.

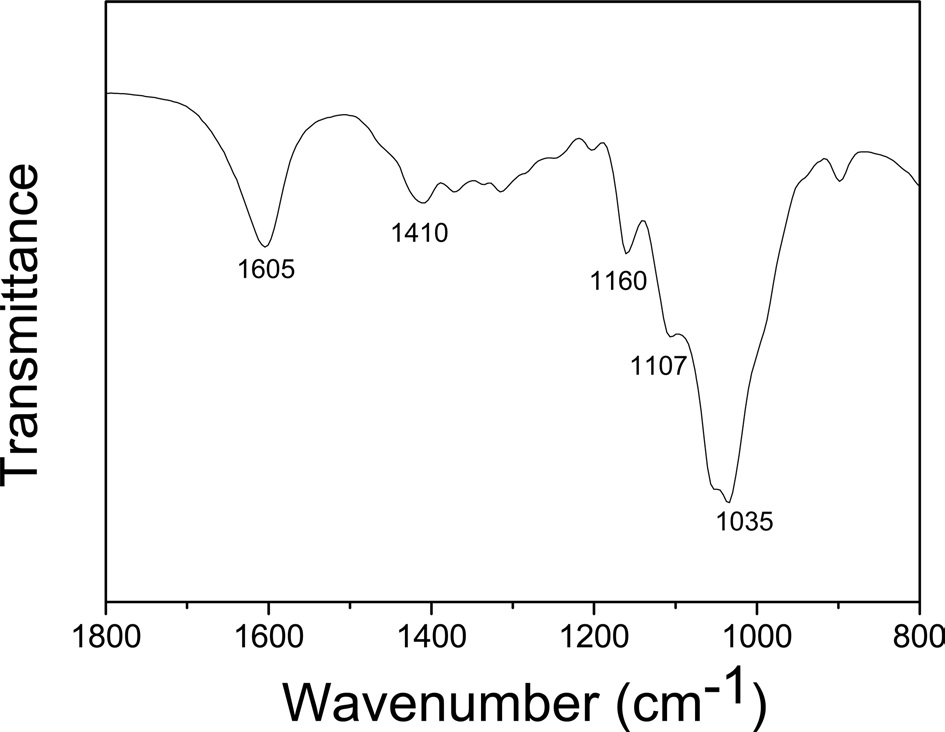

(Fig. 3) displays the FTIR spectrum of the CNFs used in this study. Strong absorption peaks appeared at 1035 cm-1, which corresponded to stretching of the C-O and C-C bonds of cellulose, and at 1159 cm-1, which could be attributed to the antisymmetric C-O-C bridge stretching (Um

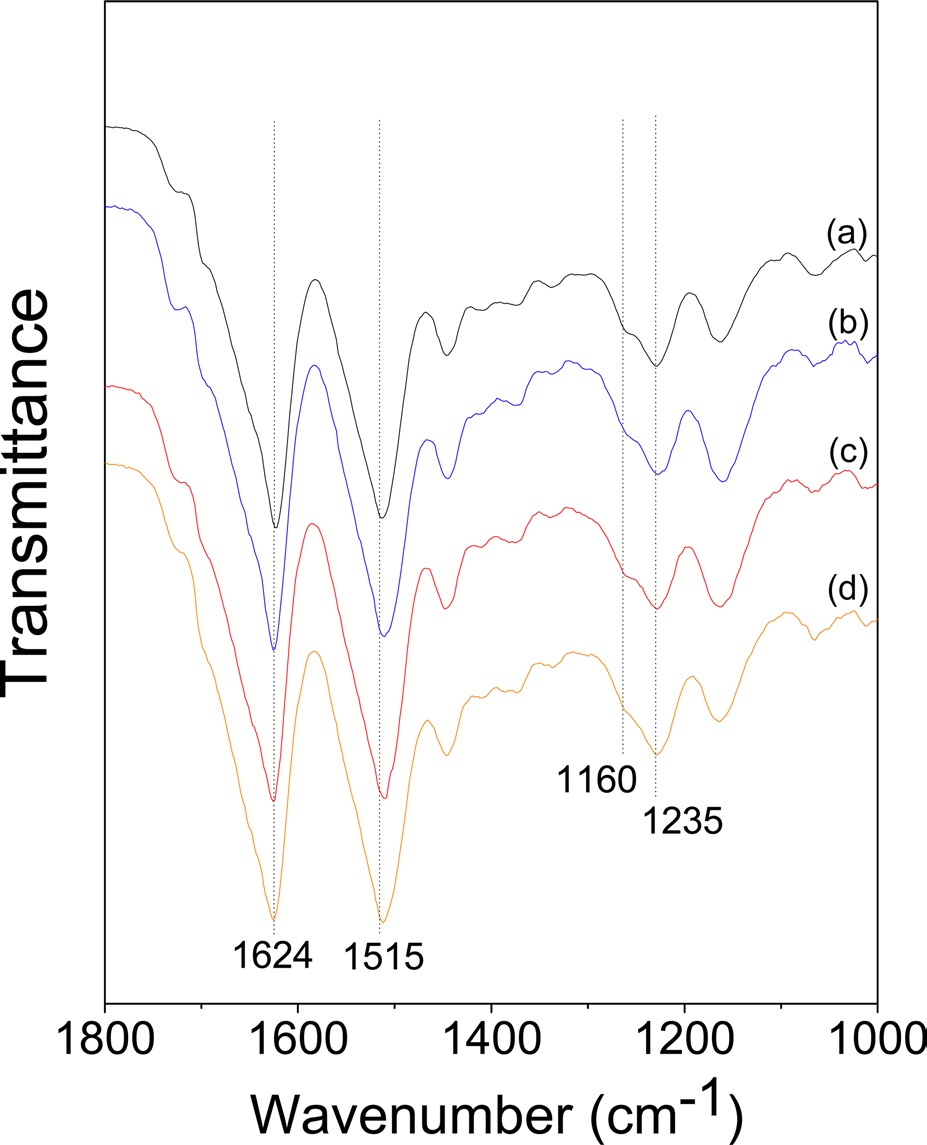

(Fig. 4) shows the FTIR spectra of wet-spun CNF/ regenerated SF composite fibers with varying CNF contents. All the composite fibers showed strong absorption peaks at 1624 cm-1 and 1515 cm-1 and a shoulder peak at 1260 cm-1. These peaks are attributed to the β-sheet conformation, indicating that β-sheet crystallites exist in all the CNF/SF composite fibers. It has been reported that β-sheet crystallization in the SF occurs when formic acid is removed (Um

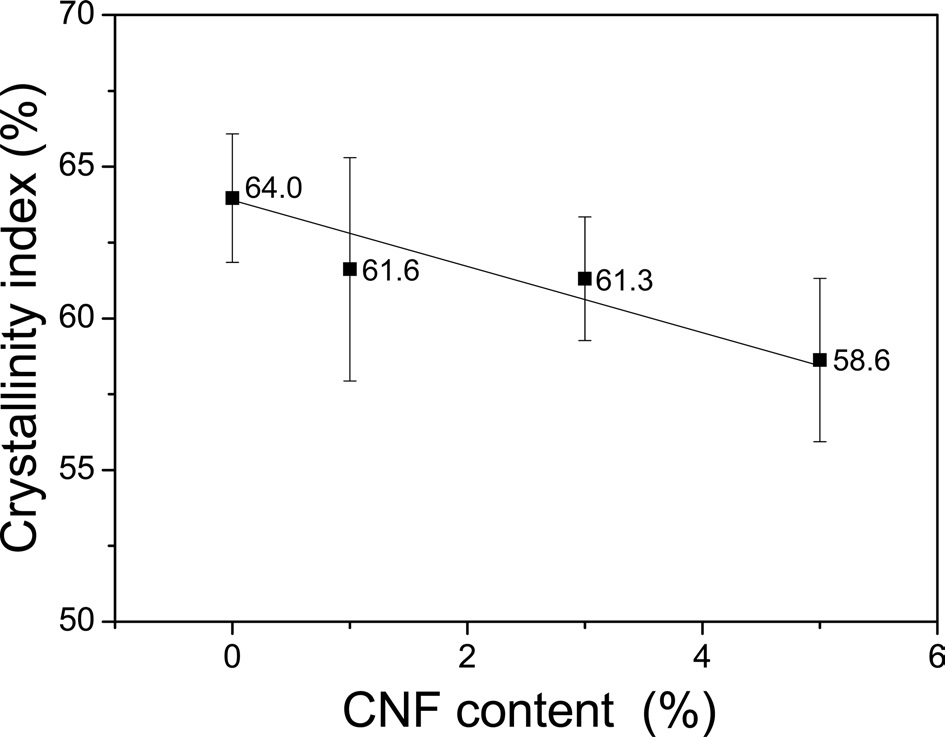

The crystallinity index of the silk proposed by Baht and Nadiger (1980) has been used to evaluate the crystallinity of the SF since it allows for a quantitative evaluation of this characteristic (Um

Therefore, detailed calculations performed to determine the crystallinity index; the results are shown in (Fig. 5). The regenerated SF filament without CNFs exhibited a

crystallinity index of 64.0%. However, the crystallinity index decreased as the amount of CNFs increased, with the 5% CNF/SF fibers showing a crystallinity index of 58.6%. This value is calculated from the IR absorption peaks in the Amide III band of SF, and it indicates the ratio of the crystalline regions to the amorphous regions of the silk. Thus, the addition of CNFs does not alter the value of the crystallinity index of the composite fibers if it has no effect on the SF. In other words, the decrease in the crystallinity index of the SF indicates that the CNFs restrict the crystallization of the SF. The SF molecules adopt the random coil conformation in formic acid solution, and β-sheet crystallization occurs in the SF fibers when formic acid is eliminated from the silk solution (Um

>

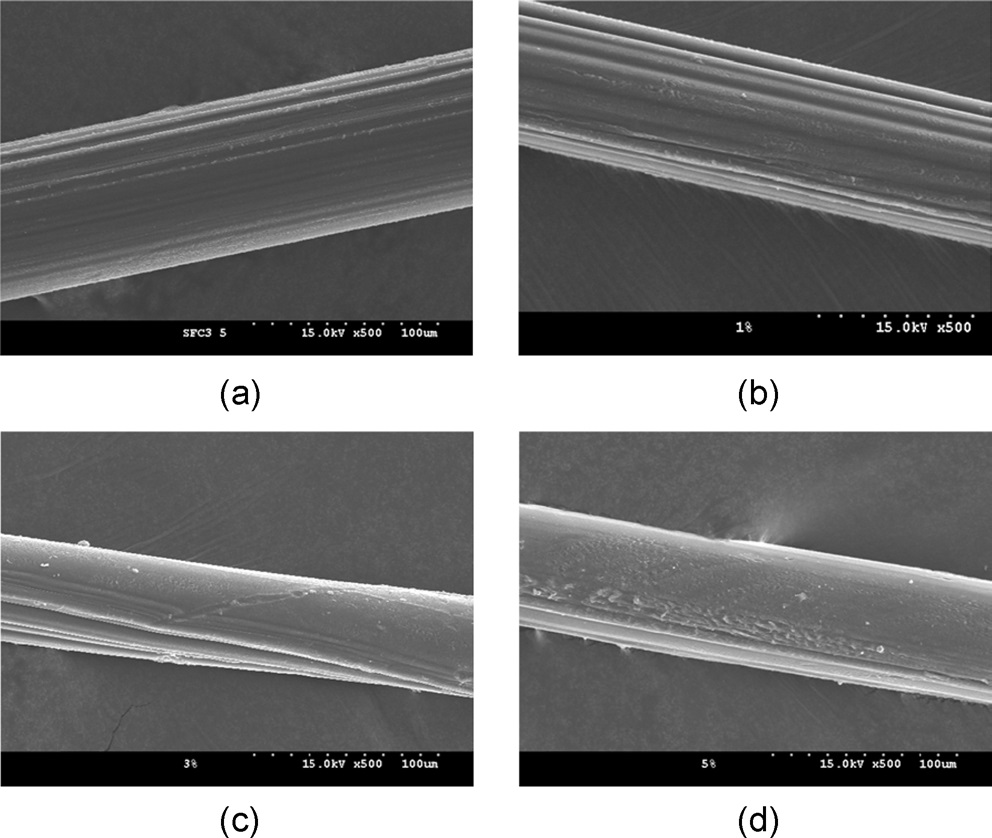

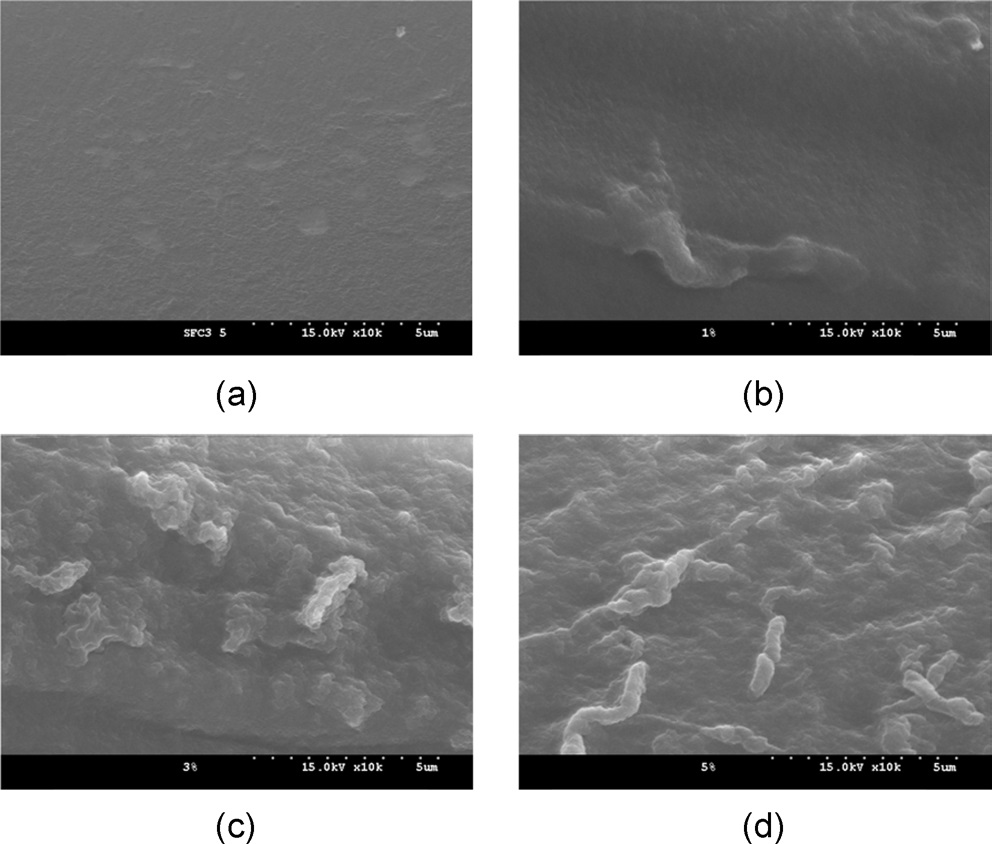

Morphology of wet-spun filament

(Figs. 6 and 7) display the surface morphology of the CNF/SF composite fibers with varying CNF contents. At a low magnification (x500, Fig. 6), the composite fiber showed stripes in the fiber axis direction, with a relatively smooth surface. Additionally, at high magnification (x10,000, Fig. 7), the regenerated SF fibers (Fig. 7a) showed smooth surfaces. However, rugged surfaces of the CNF/SF composite fibers (1?5% CNF) became visible. In particular, the rugged surfaces were more prevalent when a higher amount of CNFs was present. It seems that the rugged surface might be related to CNF aggregates, considering the fiber thickness is on the order of several hundred nanometers. This rugged surface may also be evidence for the presence of CNF aggregates in the CNF/ SF composite.