The challenge of incorporating digital channels lies in coping with the volume, nature, and velocity of the digital content for effective use (French et al., 2012). Delivering brand experience through the digital content has been of critical importance as customers demand different kinds of relationships with brands online; they check prices at a keystroke; they are increasingly selective about which brands to share their lives with; and they form impressions from every encounter and post withering online reviews. Indeed, customers desire “on-demand, personal, engaging, and networked” experiences when they search, shop, and consume products or services (Brakus et al., 2009).

As the critical moments of interaction between brands and customers are increasingly spread across multiple channels of fashion retailing, customer engagement is now every business’ priority (French et al., 2012). Customer engagement goes beyond managing different channels, as it motivates customers to invest in an ongoing relationship with a product or service (French et al., 2012). Over the past years, a wide range of fashion retail companies have tried to address customer engagement in more integrated ways; yet, companies are struggling to determine appropriate business approaches as the spectrum of consumer’s brand choices is broader than ever.

To enable customers to have experiences of a product before purchase, an increasing number of fashion retailers have begun to offer a “test drive” of the brand experience. It is thus apparent that some of the elements of the service or the product must be simulated. Edvardsson and Enquist (2010) suggest that the simulation of all or part of an experience has been referred to as “hyper-reality”. Drawn from the concept of “hyper-reality” as “. . . the multisensory, fantasy and emotive aspects of one’s experience” (Hirshman & Holbrook, 1982), several scholars have suggested that “hyper-reality” refers to a simulated (or partially simulated) service reality (Baudrillard, 1994; Edvardsson et al., 2005; Grove & Fisk, 1997; Martin, 2004; Venkatesh, 1999). Indeed, such “hyper-real” (or simulated) experiences are common in many retail services particularly in social media. The ability to create compelling experiences on social media depends on the successful facilitation of e- WOM (Chu & Kim, 2011), which leads to creative, communicative and interactive engagements in discrete experience rooms. This experiential perspective expands the scope of online consumer behavior and provides practical applications of brand experience research to the marketplace. Therefore, given Snuggie’s viral power in conjunction with its integration with pop culture, examining customer engagement exposed in social media may provide potentials to promote brands to diversified global market segments

Online customer reviews have been found to improve customer perception of social presence of the brand or product (Kumar & Benbasat, 2006). Reviews have the potential to attract consumer visits, increase the time spent on the site, and create a sense of community among frequent shoppers (Mudambi & Schuff, 2010). Compared to other online retailers or social media such as eBay or Snuggie’s official website, Amazon.com is ideal for customer engagement as its instantaneous platform enables customers to create, share, exchange and comment among themselves (Layton, 2012). Amazon customers actively share their opinions and stories by leaving their review comments, which incorporates the value of customer reviews as part of the product or brand descriptions. Aamzon.com has become the leading source of product reviews which lures more customers into the brand’s website (Mudambi & Schuff, 2010). Further, the customer review system of Amazon. com strategically allows customers to get engaged as it encourages them to respond to others’ reviews. For example, after each customer review, Amazon.com asks, “Was this review helpful to you?” and provides helpfulness information alongside the review (e.g., “26 of 31 people found the following review helpful”).

If information, consumption, and experiences are intersecting across the global market, the global fashion industry can make an informed decision and gain tools for predicting, measuring, and configuring this uncharted experiential paradigm. Yet, generalized knowledge from the conventional consumer behavior paradigm makes it difficult to address inimitable nature of multifaceted customer engagement (Kim, 2012). In order to understand customer experiential engagement in social media, this study employs Edvardsson and Enquist (2010) conceptualization of six experience rooms in hyper-reality contexts. By focusing on the Snuggie case, this study aims at (1) exploring the underlying dimensions of customer engagement in the Snuggie consumption; and (2) identifying identifying the six experience rooms from customer review comments drawn from Amazon.com. Identifying dimensions of customer engagement in the Snuggie case will provide the insights on utilizing customers’ brand and product experiences on social media.

2.1. Customer engagement in social media

Social media is a group of internet-based applications that build on the ideological and technological foundations of Web 2.0, allowing the creation and exchange of User Generated Content (Kaplan & Haenlein, 2010). Within this general definition, there are various types of social media such as Wikipedia, YouTube, Facebook, Second Life as well as blogs, twitters and many brands’ websites that need to be distinguished further. Regardless of types of social media, it allows consumers to feel emotionally connected, helps brands to achieve their marketing goals through storytelling, and establishes a personal connection with a brand (Singer, 2011). Brands can aim for maximum viral effects among engaged customers as social media allows customers to engage, seek, share, and create individual stories regarding brands (Divol et al., 2012). Although a few studies try to comprehend reliable experience dimensions relevant to social media, many scholars and practitioners are perplexed about its effectiveness; whether a social media platform can drive everything from customer relationships to product development, or if it is just another marketing tool.

When relational resources (e.g., trust, norm of reciprocity and social identity) are optimized within the virtual social networks, these motivate consumers to voluntarily share and gather information in order to reduce uncertainty, gain insights into knowledge shared in the virtual learning communities, and consume and obtain services (Koh et al., 2007; Wu & Liu, 2007). This process of building commitment is often referred to as engagement (Mathwick et al., 2008). Many scholars (Brown & Duguid, 1991; Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998; Wasko & Faraj, 2005) explicate engagement experiences as a critical element of virtual behavior, emphasizing the role of information gathering, knowledge sharing and interactive learning. Not only are users able to share information with virtual friends with common interests (Blanchard, 2004; Haubl & Trifts, 2000; Sismeiro & Bucklin, 2004), but also make contributions to knowledge building within the virtual community (Humphreys & Grayson, 2008; Ritzer & Jurgenson, 2010).

While the practitioners' view of engagement has focused on the outcome such as attaining a competitive advantage (Roberts & Lafley, 2005), the scholarly view tends to use other constructs to assess the consumer engagement experience. Mollen and Wilson (2010) have recently defined the online engagement as a cognitive and affective commitment to an active relationship with the brand as personified by the website or other computer-mediated entities designed to communicate brand value. In addition, the definition of engagement is enriched to behavioral manifestation toward a brand beyond purchase (Vivek et al., 2012). Besides the conception of emotional engagement as cognitive processes of reasoning, decision- making, problem-solving, and evaluation (Kearsley & Schneiderman, 1998), engagement is defined in relation to users’ behavioral stance as repeated interactions (Sedley, 2010), knowledge co-creation (Sawhney et al., 2005), and event or activity participation (Vivek et al., 2012). However, customer virtual engagement has not yet been fully developed into a construct as a dynamic, tiered spectrum which can capture consumer’s virtual behavior (Doorn et al., 2010; Vivek et al., 2012).

Customers tend to engage with social media when they perceive a balance between intrinsically pleasing tasks and self-reinforcement with the prerequisite of seamless virtual experience that allows them to navigate, search, and experience products or services. However, current literature lacks the examinations of multifaceted virtual experiences that incorporate engagement, emotion, cognition and behavior. In addition, there are limited studies focusing on brand experience in individual contexts that direct web usage outcomes. Therefore, this study aims to conceptualize customer brand engagement which has discrete underlying experience rooms following the framework of Edvardsson and Enquist (2010).

2.2. Six experience rooms in social media

Customer experience is defined as a customer’s subjective interpretation of their experience with a brand (Frow & Payne, 2007). When the fashion retail company becomes customer experience oriented, the company changes from the traditional marketing to a holistic approach to co-creation of customer experience. For a positive customer experience, Gentile et al.(2007) suggest that customers should have multidimensional experience composing of cognition, affect and sensation, which depends largely on interaction between customer and brand. Thus, brand must provide the necessary stimuli and the right context for this co-creation of experience to take place (Wyner, 2003).

In this necessity, many brands offer test-drives or pre-purchase experience of their products and service while providing information through brochures, videos, or website. Recently, Edvardsson and Enquist (2010) developed the concept of the “experience rooms,” in which test-drives take place. They specify six dimensions of “experience rooms” in physical or virtual environments as follow: physical artifacts, intangible artifacts, technology, customer placement, customer involvement, and interaction with employees.

2.2.1. Physical artifacts

It pertains to physical signs, symbols, and infrastructures necessary to create the physical attributes of the “experience room” (Arnould et al., 1998; Bitner, 1992; Edvardsson et al., 2005; Normann, 2001; Venkatesh, 1999). Physical artifacts of experience room might directly influence customer experience across diverse type of brands, products, and stores features. For example, Bitner (1992) suggests that the physical environment of store conveys implicit and explicit signals about the place to communicate with its consumers.

2.2.2. Intangible artifacts

It stands for the non-physical infrastructure that includes mental images, brand reputation, narratives, norms, themes, and values (Bitner, 1992; Normann, 2001). Intangible components induce a positive experience and are often perceived as brand message that conveys company’s culture and strategy. They let individual or groups of customers imagine positive feelings and value that brand, products and service can generate. Experiences through pictures, movies, music, and activities in relating product and service can help customers envisage and create a realistic pre-purchase experience; thus, they can be considered as intangible artifacts (Edvardsson et al., 2005). Direct and indirect influences of intangible artifacts are well represented in many symbolic and luxury brand experience. Edvardsson et al.(2005) suggest that catalog influences customer engagement directly and indirectly, as an intangible artifact.

2.2.3. Technology

It refers to the technological equipment with which customers interact, either actively or passively (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, 2003; Venkatesh, 1999). While technology is often perceived as the tool of information and communication apparatus, scholars (Edvardsson et al., 2005) suggest that technology can provide hyper-reality through simulations. Indeed, such “hyper-real” (or simulated) experiences are common in many “everyday” virtual services. For example, people experience a travel destination or a hotel by experiencing a virtual tour in which experience is simulated in various ways while others visit an online store of a fashion brand to experience simulated settings and events of various sorts. These experiences and settings are engineered to allow consumers to vicariously experience brands, products or services. As such, a customer’s interaction with hyper-reality can create an experience that is more distinct, unambiguous, powerful, and believable, which ultimately impacts customer purchasing behaviors. Technology also conveys the quality perception through meaning, arousal, and excitement from the activities and the service process. Particularly, self-service technology may change the role of the customer with regard to the co-production and co-creation of experiences (Edvardsson et al., 2005; Prahalad & Ramaswamy, 2003). When consumers co-create the brand experience through their social relationship within a virtual community, they virtually engage in searching, sharing, creating, purchasing, and entertaining behaviors. These intersecting roles between consumers and producers, which often lead to collaboration among consumers, are becoming popular in social network sites such as Facebook and Twitter (Ritzer & Jurgenson, 2010).

2.2.4. Customer placement

It refers to the precondition for interactions with others and product, and the creation of service encounters and events in a defined physical and hyper-real environment in which the customer is placed and staged (Edvardsson et al., 2005). Customer placement focuses on extrinsic experiences associated with consumer’s cognitive and emotional structure.

2.2.5. Customer involvement

Involvement results from an interaction between person, stimulus, and situation (Swaminathan et al., 1996). Customer involvement relates to connections or references per minute that the viewer makes between his own life and stimulus. Edvardsson et al. (2005) focus on how individual customers engage with preferable experiences from the interaction with services and situations.

2.2.6. Interaction with employees

Interaction with employees has a strong impact on customer experience (Edvardsson & Enquist, 2010). It refers to the consumers’ ability to interact with service providers to gain useful information for the potential purchase decision in the “experience room.” Interaction with employees can be a crucial dimension for some service contexts, in such case as the physical stores and show

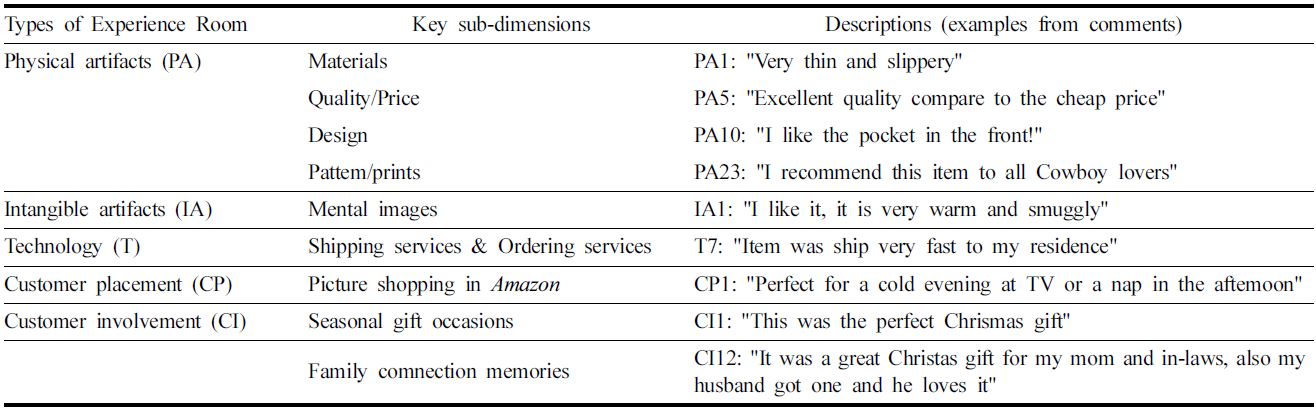

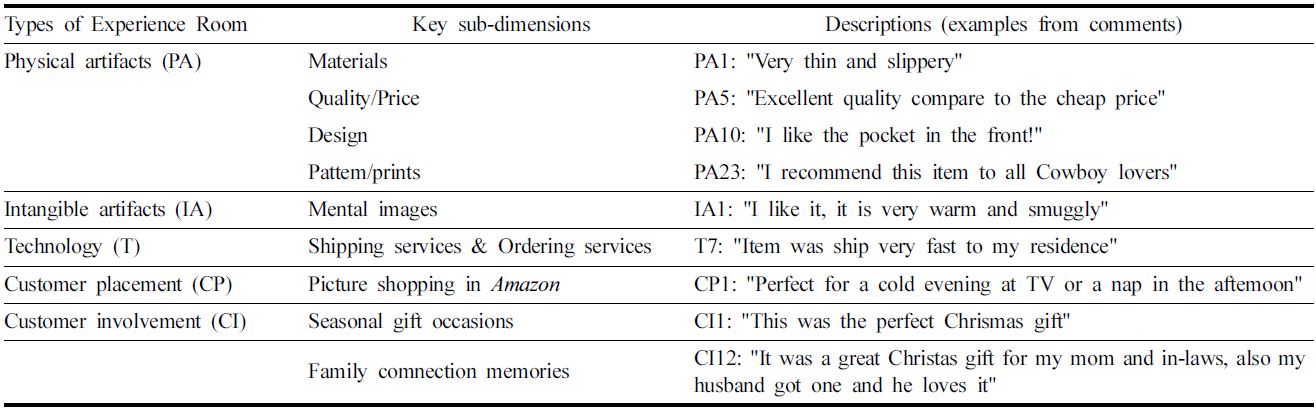

[Table 1.] Customer responses of Snuggie

Customer responses of Snuggie

rooms. Many customers perceive the personal interactions as main drivers of their experience and significant factors of their decision making in the physical store. Thus, companies should provide opportunities for the customers to interact with its employees in the “experience room”, even through web sites (Edvardsson & Enquist, 2010).

3.1. Data collection and analysis

By employing content analysis of customer reviews, the qualitative study explored customers’ Snuggie experience incorporated in the social media, Amazon.com. The content analysis is pertinent to assess average phenomena of a culture (Shaw, 1984). Countless word clusters have been compared to determine patterns of ideas and themes and to make valid inferences from comments (Anderson et al., 2001). In relation to the Snuggie brand or product, a total of 742 customer reviews posted on Amazon.com during six months from September 2011 to February 2012 was retrieved. Upon compiling all reviews and deleting redundancies, a total of 364 responses were compiled for the content analysis. By conducting the constant comparative method and open coding (Kim et al., 2007), broad themes were identified, and then subthemes were traced and analyzed to create a unit of meaning. Following the elimination of superfluous phrases and sentences, themes and subthemes were coded. After the coding of each review, relationships between themes and subthemes for each question across review comments were analyzed and conceptually labeled.

Eleven key words were extracted and grouped, applying the framework of six experience rooms (Edvardsson & Enquist, 2010) with inter-coder reliability of 0.86 to verify the accuracy and reliability of the coding. Upon compromising the disparities between two coders, as a result, five experience rooms were identified as “physical artifacts”, “customer involvement”, “intangible artifacts”, “technology”, and “customer placement” (Table 1).

By examining Snuggie customers’ responses posted in Amazon. com, this study profiles five experience rooms where customers experience products, services, and brand significantly and meaningfully. Expressively (Table 2), it was hardly expected to expose the experience room of “Interaction with employees” due to Snuggie’s virtual social networking context.

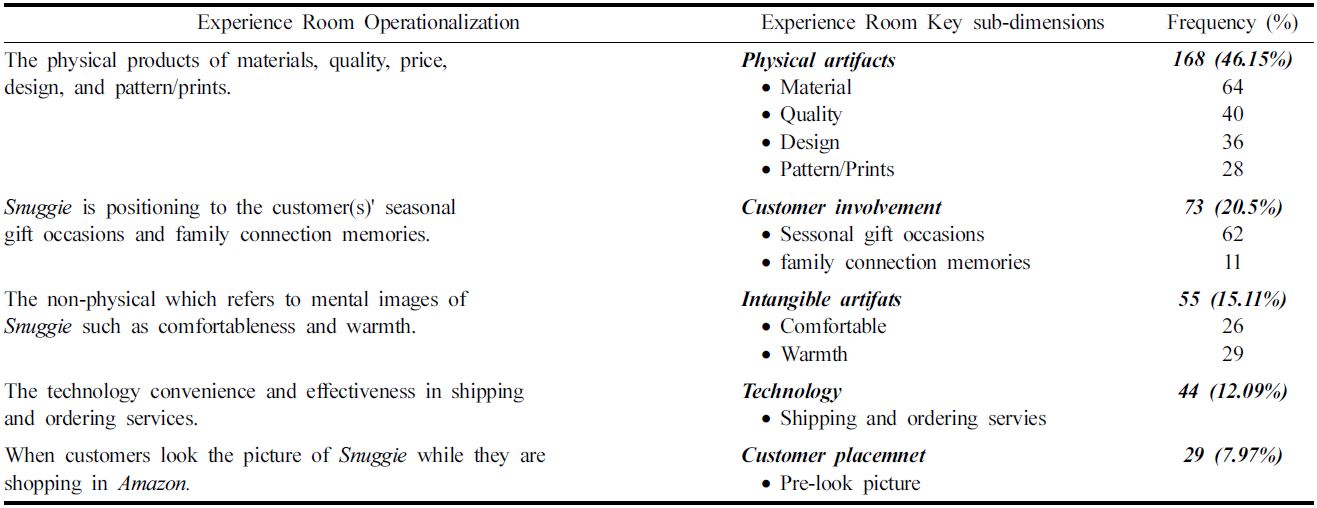

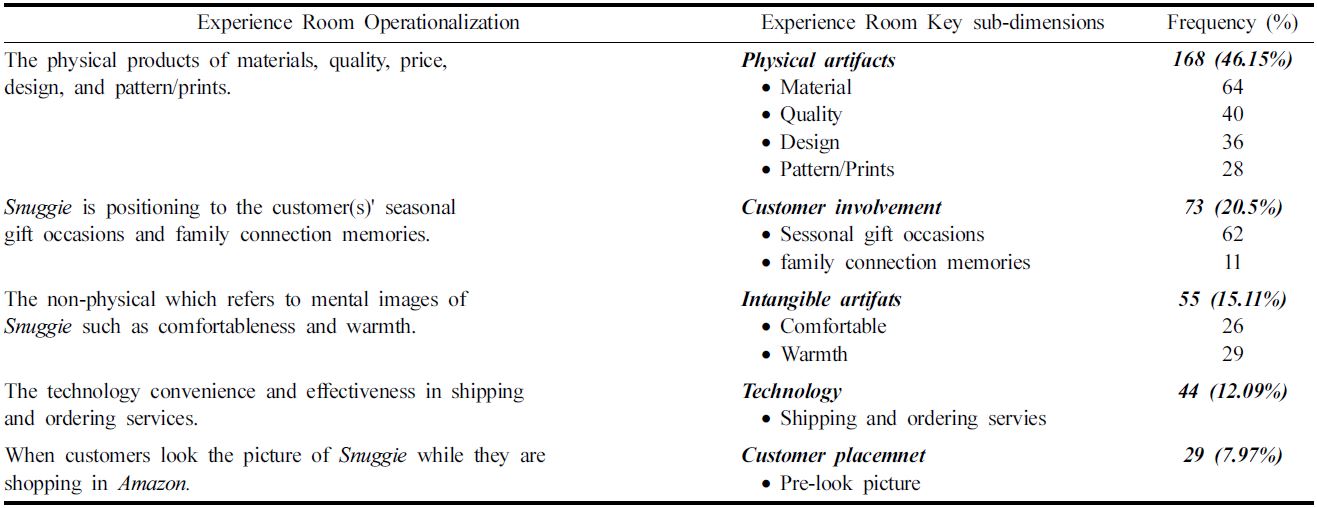

A total of 168 responses (46.15%) posted in Amazon.com is related to the “physical artifacts” experience room with key words of materials, quality, price, design, and pattern/prints in conjunction with their preference. The salient response (n=64) concentrates the product attributes of thickness, texture, length, and size: “very thin and slippery” (PA1); “the fleece is thin that a little light passes” (PA25); and “the fabric looks very good” (PA15). The second group of response (n=40) highlights customers' satisfaction over the quality and the price of Snuggie product: “excellent quality compares to the cheap price” (PA5); and “it is well cut and sewn properly” (PA55). The third response group (n=36) describes the design feature such as open back and big pocket. Some customers like the design, while others do not like the design and feel uncomfortable: “I like the pocket in the front!” (PA10); “it’s better than a robe because it cover your feet” (PA67); and “it’s really nice to be able to use your hands … but the sleeves are loose and large enough to cover hands if you don’t want to have them open” (PA79). The fourth group of responses (n=28) describes their preference for their favorite sports-team prints over personal favorite colors or patterns. “Gift for my parents who have been huge Packer fans” (PA120). “This is also his favorite team” (PA115). “I recommend this item to all Cowboy lovers” (PA23). “I recommend this product because it can be customized for many different sports teams” (PA132).

[Table 2.] Profiling of five experience rooms

Profiling of five experience rooms

Interestingly, the second experience room is depicted as “customer involvement” (n=73) with the key words of seasonal gift occasions and family connection memories intrinsically. Many female consumers purchase Snuggie as a Christmas gift to their family for fun memories of wearing it together. “I ordered eight of these as gifts” (CI21). “Bought four Snuggies from Amazon.com” (CI18). “This was a gift from my cousin this year” (CI54). “I purchase the Snuggie for my wife as a sort of gimmicky gift for Christmas” (CI7). “This was the perfect Christmas gift” (CI1). “It was a great Christmas gift for my mom and in-laws, also my husband got one and he loves it” (CI12). “I saw one on Amazon.com and got it for my daughter’s Christmas gift and she likes it and I bought a couple more for gifts more my young niece and nephew” (CI29). “One year for Christmas, my mom thought she was cute and funny and got me and my husband Snuggie” (CI5).

For the third experience room, a total of 15.11 % (n=55) responses refers to “intangible artifacts” reflecting two key words of comfortableness and warmth, which are of mental images of Snuggie. Interestingly, customers highly value Snuggie when they are satisfied with intangible artifacts (comfortableness and warmth) in conjunction with physical artifacts (quality and price). “I like it, it is very warm and snuggly” (IA1). “Very soft and comfortable” (IA16). “Just enjoy the warmth!” (IA27). “Great for staying warm and cozy!” (IA44).

With key words of shipping and ordering services efficiencies based on the advancement of technology, a total of 12.09 % customers (n=44) consider the fourth experience room as “technology” experience which emphasizes the technological convenience and effectiveness. When Snuggie products arrive at the right time, the extent of customer satisfaction and involvement are increased. Since many customers purchase Snuggie as seasonal gifts, customer satisfaction is directly related to the on-time shipping. Customers also believe the ordering effectiveness is derived from technology. “Thank you, the package arrived on said date and even though the packaging was a bit buster up the content inside seems fine and looks of nice quality” (T2). “Item was ship very fast to my residence” (T7). “The merchandise arrived in great condition in a timely manner” (T32).

The fifth experience room is “customer placement” experience based on 29 responses (9.97 %) with the key word of pre-look picture. When customers look the picture of Snuggie product while they are shopping in Amazon.com, they want to use it during winter for their comfort at home, and/or to buy it for gift of specific occasions. Consumers interact with other customers, products, and service encounters in a defined physical and hyper-real environment (Sherry, 1995). “I used it all of last winter, and now am using it again, as even in North Florida we find ourselves in below freezing temps” (CP17). “Perfect for a cold evening at TV or a nap in the afternoon” (CP1).

Customer’s engagements in social media are becoming increasingly recognized as the driving force behind many of the fashion retail companies. By employing the experience room perspective of Edvardsson and Enquist (2010) in the virtual context, this study profiles the emerging sentiment of customer engagement with a brand in social media. The presence of customer reviews on social media has been shown to improve customer perception of the usefulness and social presence (Kumar & Benbasat, 2006). Upon analyzing a total of 364 customer responses about Snuggie in Amazon.com, five experience rooms were exposed. “Physical artifacts” and “customer involvement” are influential experience rooms which signify interactions between products and customers, while “intangible artifacts”, “technology” and “customer placement” reflects a lower degree of experiential engagement with Sunggie brand. In addition, the eleven key words pertain to marketing implication for fashion retail brand in the social media environment.

Sunggie customers mostly engaged in tangible artifacts of product including thickness, texture, length, and size. This finding is consistent with many conventional studies despite the currency of new product and new market environment. For example, Abraham- Murali and Littrell (1995) argued that styling was the influential factor in purchase intention followed by fabric, color/pattern/ texture, and construction. Due to the unique features of Snuggie product and Amazon.com’s virtual nature, tangible artifacts often affect consumer perception and purchase intention. The second experience room is customer involvement with seasonal gift occasions and family connection memories. It is identical in many ways to the types of consumption collectivities that marketers and researchers are interested in cultures and brand communities (Kozinets et al., 2008). When customers share their Snuggie experiences in the customer involvement room, Amazon.com bridges an individual customer experience to the collective context in which Snuggie combines memories and profit, adult-like utility and the childlike wonder of play.

Besides two core experience rooms, intangible artifacts, technology, and customer placement experience rooms support customers’ interaction with other customers, products, and service encounters in a defined physical and hyper-real environment where customers are placed and staged (Sherry, 1995).

However, this study is not able to explicate the experience room of “interaction with employees” due to Snuggie’s product and service feature provided from Amazon.com. The conceptualization of five experience rooms is consistent with the initial study (Edvardsson et al., 2005) of the prepurchase service experience. Nevertheless, Edvardsson and Enquist (2010) recently emphasized “interaction with employees” experience dimension in analyzing the IKEA showroom and the MBA program experiences since many customers perceive personal interactions as key drivers and significant factors in their decision making (Edvardsson & Enquist, 2010). Indeed, fashion retail companies designing “test drives” in social media should enhance opportunities for interaction, even via their web sites.

Nowadays, various social media outlets (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, Instagram) are available to engage customers to become brand fans. In this environment, profiling the social media experience could be a useful tool for brands (Divol et al., 2012). Such profiling should be hardwired into the business to shorten response times during real and potential crises, complement internal metrics and traditional tracking research on brand performance, give consumer feedback into the product-development process, and serve as a platform for testing customer reactions. More customer interactions across multiple touch points are shaping the degree of consumer engagement.

This study provides a theoretical foundation for understanding the concepts of customer engagement in social media. However, given the exploratory nature of this approach, there are limitations in generalizing these findings. First, the purposive sampling from a particular brand (i.e., Snuggie) from a single social media (i.e., Amazon.com) limits the generalization of the research by restricting the number of experienced customers incorporated in the study. A sampling of customers of various different brands in the same product category may lead to in depth results. Further, cultural and case specific discrepancies need to be considered in future studies. Second, upon reviewing the various dimensions of customer experience through social media, the multi-dimensionality may better capture the multi-faceted relationship resources involved in the channel. Exploring social media and customer experience engagements in the general virtual context may insightfully portray relationship resources and personal commitment towards the virtual environment. Specifically, the sixth dimension of “interaction with employees” was not found in this study, as the nature of social media does not involve customers’ direct interaction with the employees. Third, the study does not fully cover emotional and behavioral aspects of engagement because of the limited number of review comments from a social media. If future study would conduct in-depth interviews, it could enrich the conceptualization that can be incorporated into future studies. Lastly, purchase intention was not explicitly considered in this study. In future research, purchase behavior and e-WOM effect in collective social media context might provide diverse theoretical comprehension.

Beyond these limitations, there are various directions for marketing implications. For the managerial perspective, the customer experience in a call center can be coordinated with the behavior of frontline employees or the online registration experience with product development. In addition, professional designers’ reviews or recommendations about a product using video demonstration may enrich the brand and product experience. However internal resources probably won’t be able to deliver all of the requirements imposed by a world with many touch points: for instance, content and communications; data analytics and insights; product and service innovation; customer experience design and delivery; and managing brand, reputation, and corporate citizenship (French et al., 2012). Companies need to create a supply chain of increasingly sophisticated and interactive content to feed consumer demand for information and engagement, not to mention a mechanism for managing the content consumers themselves generate.