There can be little question that molecular techniques have radically altered the face of phycological research especially in the fields of biodiversity and systematics (Maggs et al. 2007). Whereas in the early years researchers focused strongly on two commonly used markers, viz., the plastid

In this review, we focus strictly on the primers, profiles and strategies for the PCR amplification of markers currently in use in our lab (for a review of current collection and DNA extraction protocols see Saunders and McDevit 2012). Being partners in both the DNA barcode and Red-

ToL initiatives, we have been heavily involved in marker development and refinement to meet their respective objectives. As a result, numerous changes have been introduced to “tried and true” markers in an effort to improve universality.

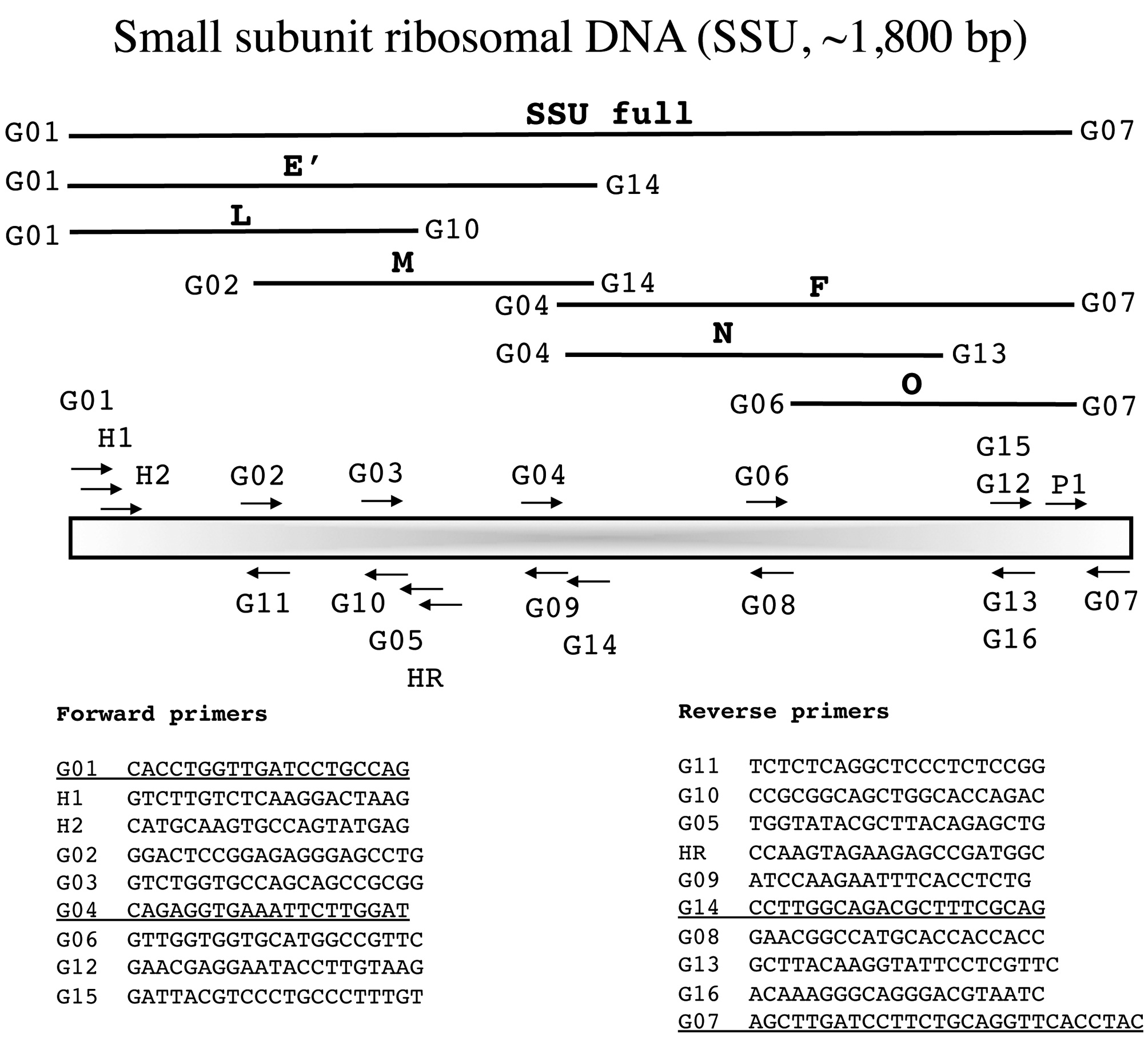

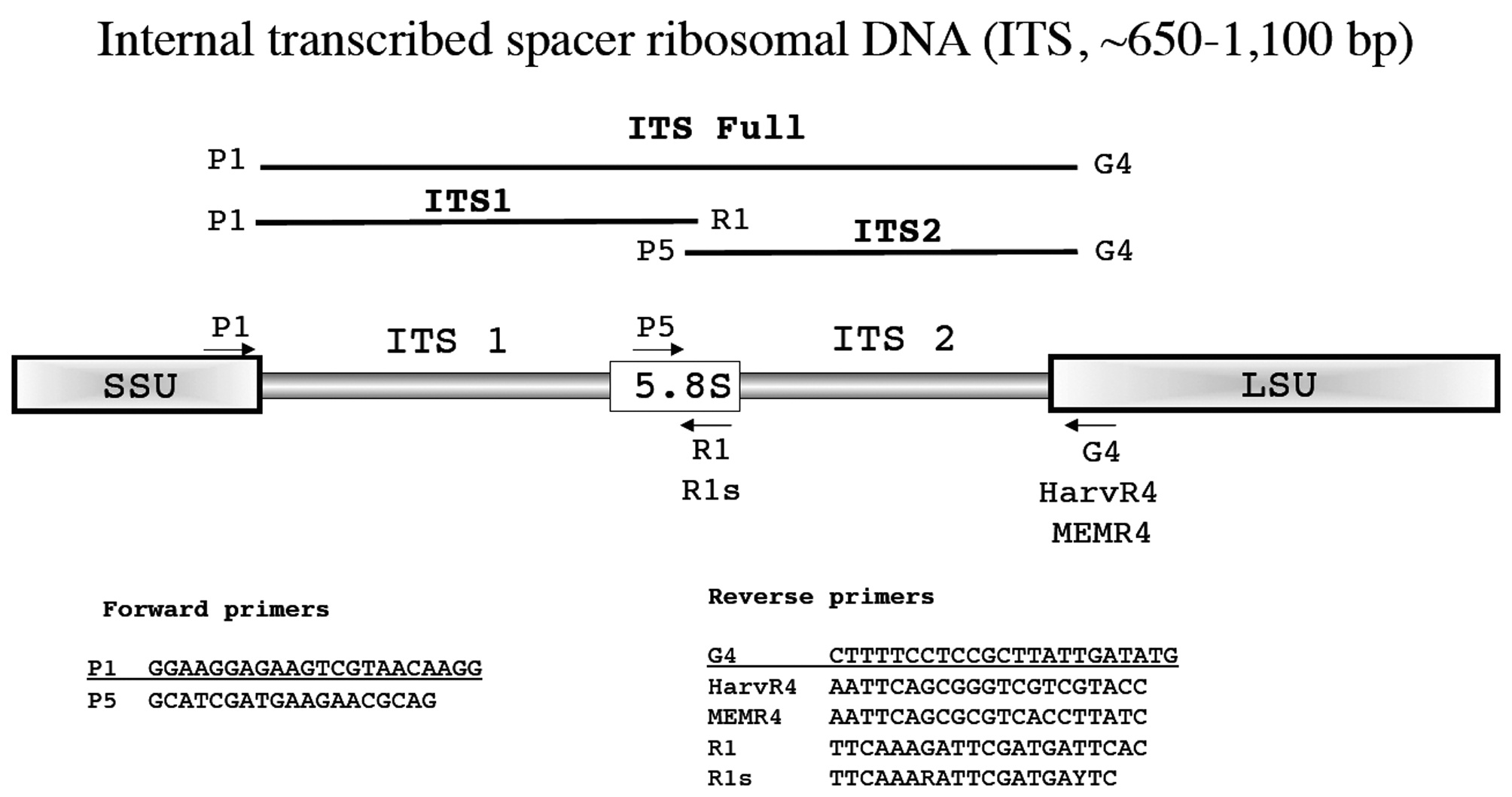

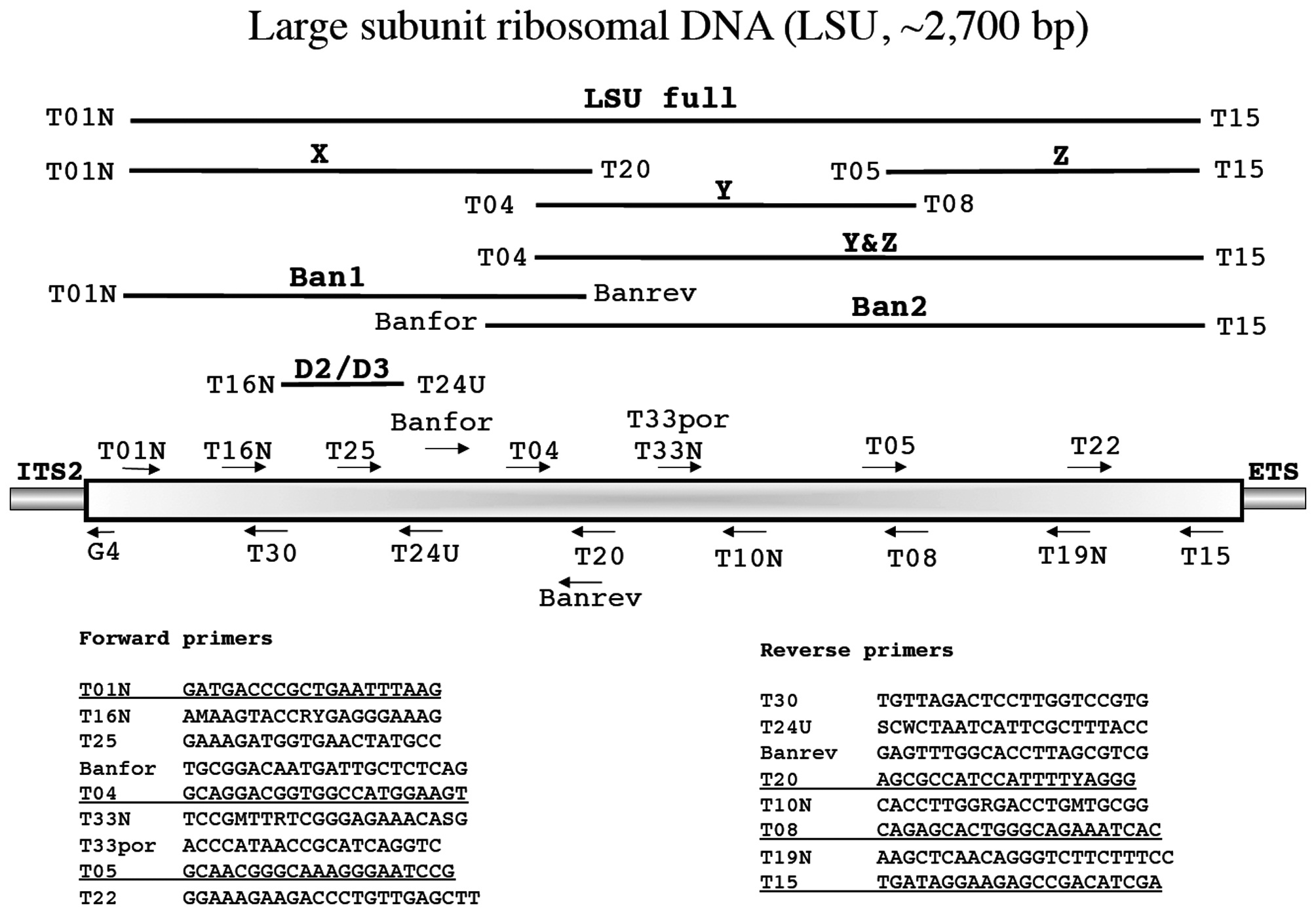

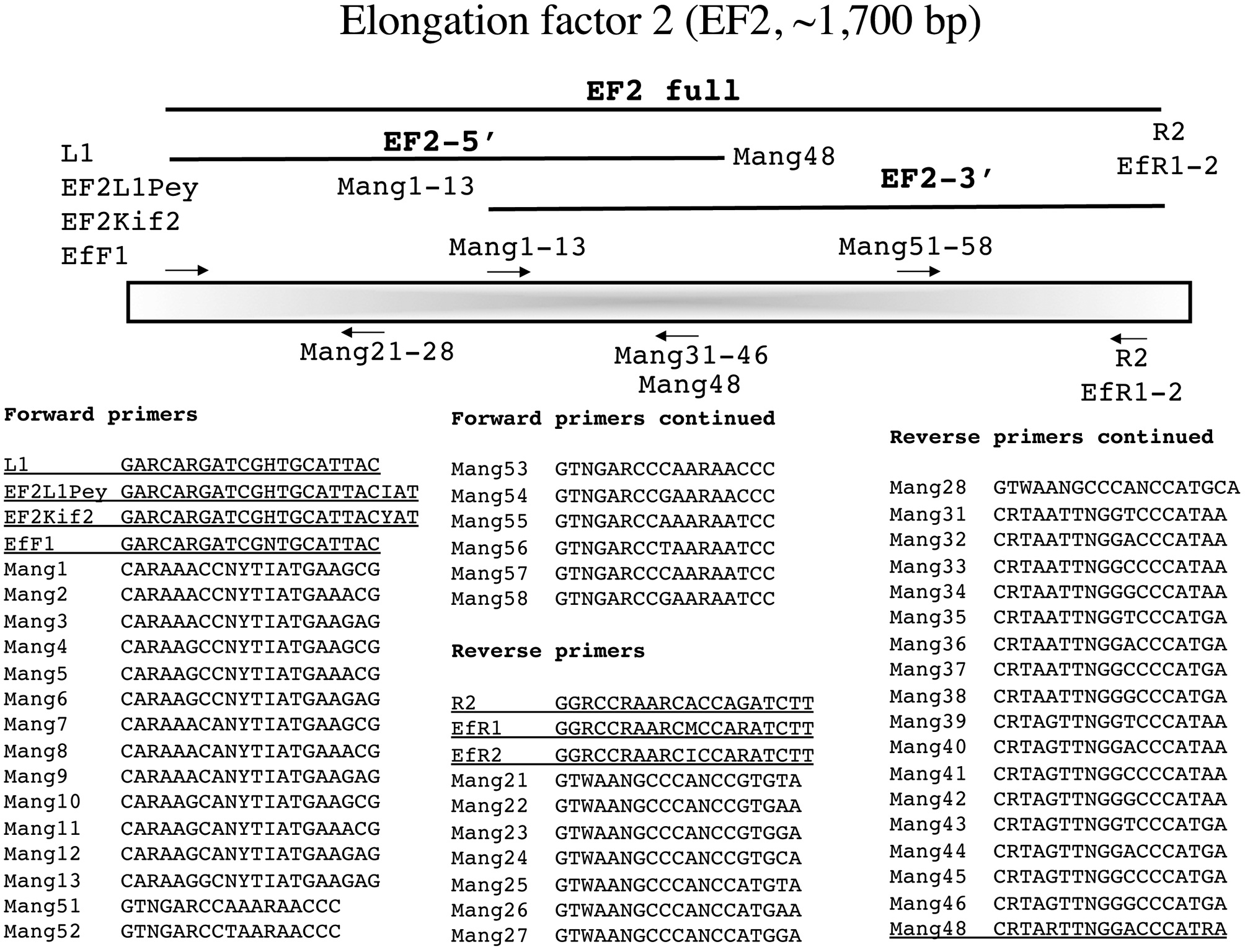

In the following section each marker has a brief summary with a corresponding figure. We have tried to adhere to the same format for all figures?from top to bottom (examples refer to Fig. 1): marker name (e.g., small subunit ribosomal DNA), acronym (e.g., SSU), and approximate size (e.g., ~1,800 bp); a schematic of the fragment(s) typically amplified for each marker, their corresponding acronym / name and the primers used to amplify them when more than one fragment is an option (e.g., E', a fragment corresponding to the 5' end of the SSU is amplified with G01 and G14); a schematic showing the relative location of all primers along the marker (gene regions presented as wider boxes than adjacent spacers); and finally a listing of the actual PCR / sequencing primers. The typical primers used for PCR amplification are underlined for each marker, while M13 linkers and sequencing primers are indicated in bold italics type.

>

Small subunit ribosomal DNA (SSU, ~1,800 bp)

The SSU was widely used in early studies of red algal phylogenetics (e.g., Bird et al. 1992, Ragan et al. 1994, Saunders and Kraft 1994) and is still useful for exploring deeper relationships (e.g., West et al. 2008) with Harper and Saunders (2001

Amplification profile: 94℃ for 4 min; 38 cycles of 94℃for 30 s, 55℃ annealing for 30 s, 72℃ extension for 1 min 30 s; followed by 72℃ final extension for 7 min.

>

Internal transcribed spacer ribosomal DNA (ITS, ~650-1,100 bp)

First investigated for red algae by Steane et al. (1991), the ITS marker is useful for species discrimination and detecting hybridization, in some cases population level analyses, and for resolving relationships among closely related taxa. Our default methodological reference for ITS amplification is Tai et al. (2001) or, more recently, Saunders and McDevit (2012) with our overall scheme first summarized in Harper and Saunders (2001

Amplification profile: 94℃ for 2 min; 38 cycles of 94℃for 30 s, 50℃ annealing for 45 s, 72℃ extension for 2 min; followed by 72℃ final extension for 5 min.

>

Large subunit ribosomal DNA (LSU, ~2,700 bp)

Freshwater and Bailey (1998) first used the LSU as a phylogenetic tool for red algae while Harper and Saunders (2001

(2001

Amplification profile: 94℃ for 5 min; 38 cycles of 94℃for 30 s, 50℃ annealing for 30 s, 72℃ extension for 2 min; followed by 72℃ final extension for 7 min.

>

Elongation factor 2 (EF2, ~1,700 bp)

Le Gall and Saunders (2007) championed EF2 as a phylogenetic marker for red algae in a survey of Florideophyceae. In that study this region was amplified as a single product ~1,700 bp in length or as two shorter overlapping fragments (Le Gall and Saunders 2007, Fig. 1). In pursuing this marker for additional taxa we have had mixed success for both amplification with their external PCR, as well as for sequencing with their internal primers, and it is not uncommon for species within a genus to require different primers. This has resulted in numerous, ongoing modifications to the original system. We currently amplify the entire fragment trialing combinations of external forward and reverse PCR primers to find the combination that works best for a sample (Fig. 4). Typically the original L1 or the modified EF2L1Pey work in combination with R2 or the modified EfR1 (trial progression for an isolate moves from L1-R2 then EF2L1Pey-EfR1 then Ef2Kif2- EfR1). Recently we have attempted to acquire EF2 from difficult taxa by amplifying the various forward primers against the internal reverse primer Mang48 to acquire an EF2-5' fragment (Fig. 4). We then sequence with the external PCR primers and use those data to identify the best internal forward primer from the Mang1-13 series to use against our external reverse PCR primers to amplify the EF2-3' fragment (Fig. 4). In all cases, we sequence with the PCR primers and use those data to select the best internal sequencing primers from the forward series Mang1-13 and Mang51-58 and from the reverse series Mang21-28 and Mang31-46 (Fig. 4).

Amplification profile for full fragment: 94℃ for 4 min; 38 cycles of 94℃ for 1 min, 50℃ annealing for 1 min, 72℃extension for 2 min; followed by 72℃ final extension for 7 min.

Amplification profile for two subfragments: 94℃ for 4 min; 38 cycles of 94℃ for 1 min, 58℃ annealing for 1 min, 72℃ extension for 2 min; followed by 72℃ final extension for 7 min.

>

Photosystem I P700 chlorophyll a apoprotein A1 (psaA, ~1,600 bp)

Yoon et al. (2002) devised an amplification strategy for

Amplification profile: 94℃ for 2 min; 5 cycles of 94℃for 30 s, 45℃ annealing for 30 s, 72℃ extension for 1 min; then 35 cycles of 94℃ for 30 s, 46.5℃ annealing for 30 s,

72℃ extension for 1 min; followed by 72℃ final extension for 7 min.

>

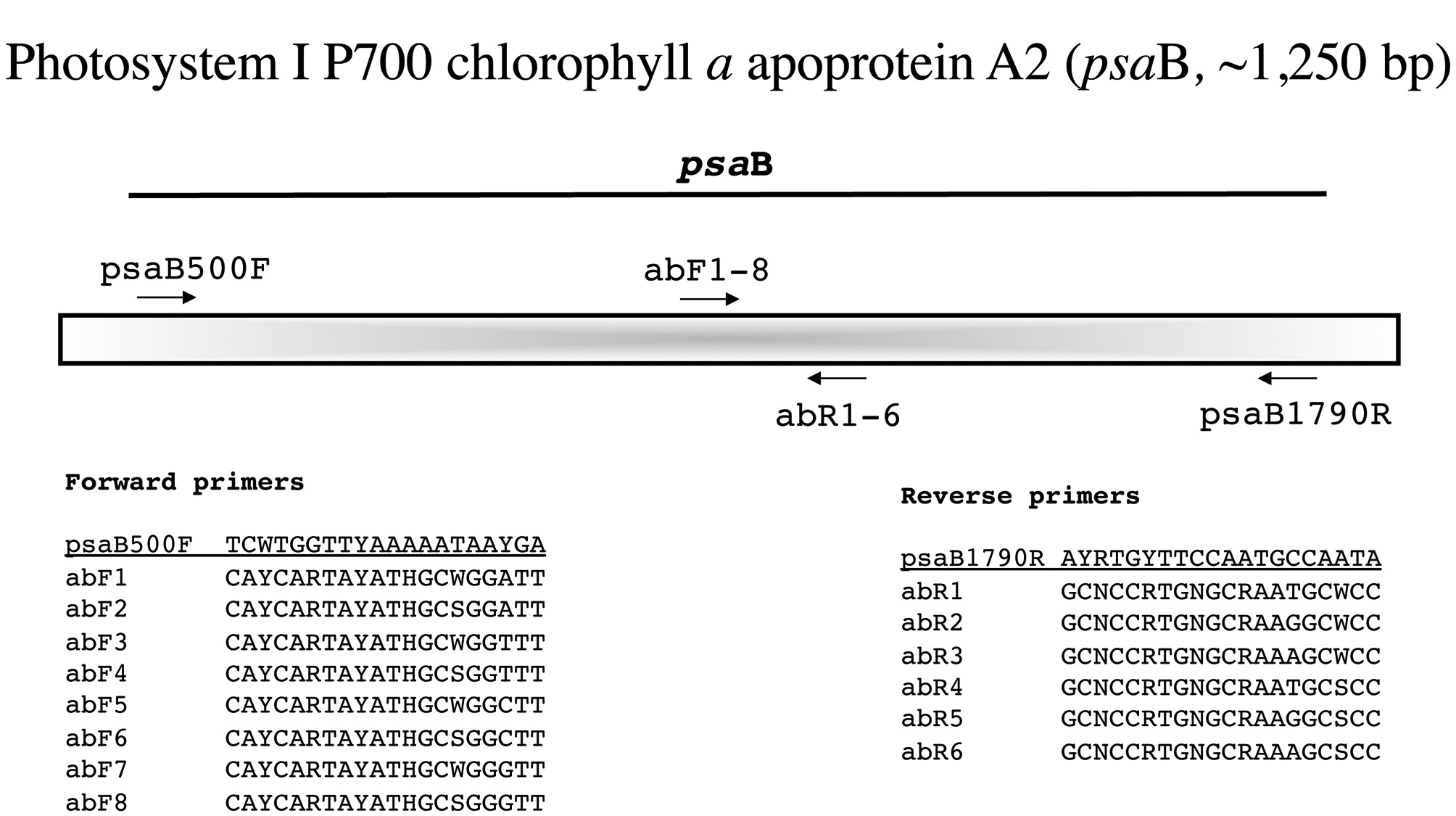

Photosystem I P700 chlorophyll a apoprotein A2 (psaB, ~1,250 bp)

For this marker the external PCR primers are from Yoon et al. (2004) and again we amplify it as a single fragment (Fig. 6). As with the previous markers, we generate se-quence with the PCR primers and then identify the best internal forward and reverse primers from our newly developed series abF1-8 and abR1-6, respectively (Fig. 6).

Amplification profile: 94℃ for 2 min; 5 cycles of 94℃for 30 s, 45℃ annealing for 30 s, 72℃ extension for 1 min; then 35 cycles of 94℃ for 30 s, 46.5℃ annealing for 30 s, 72℃ extension for 1 min; followed by 72℃ final extension for 7 min.

>

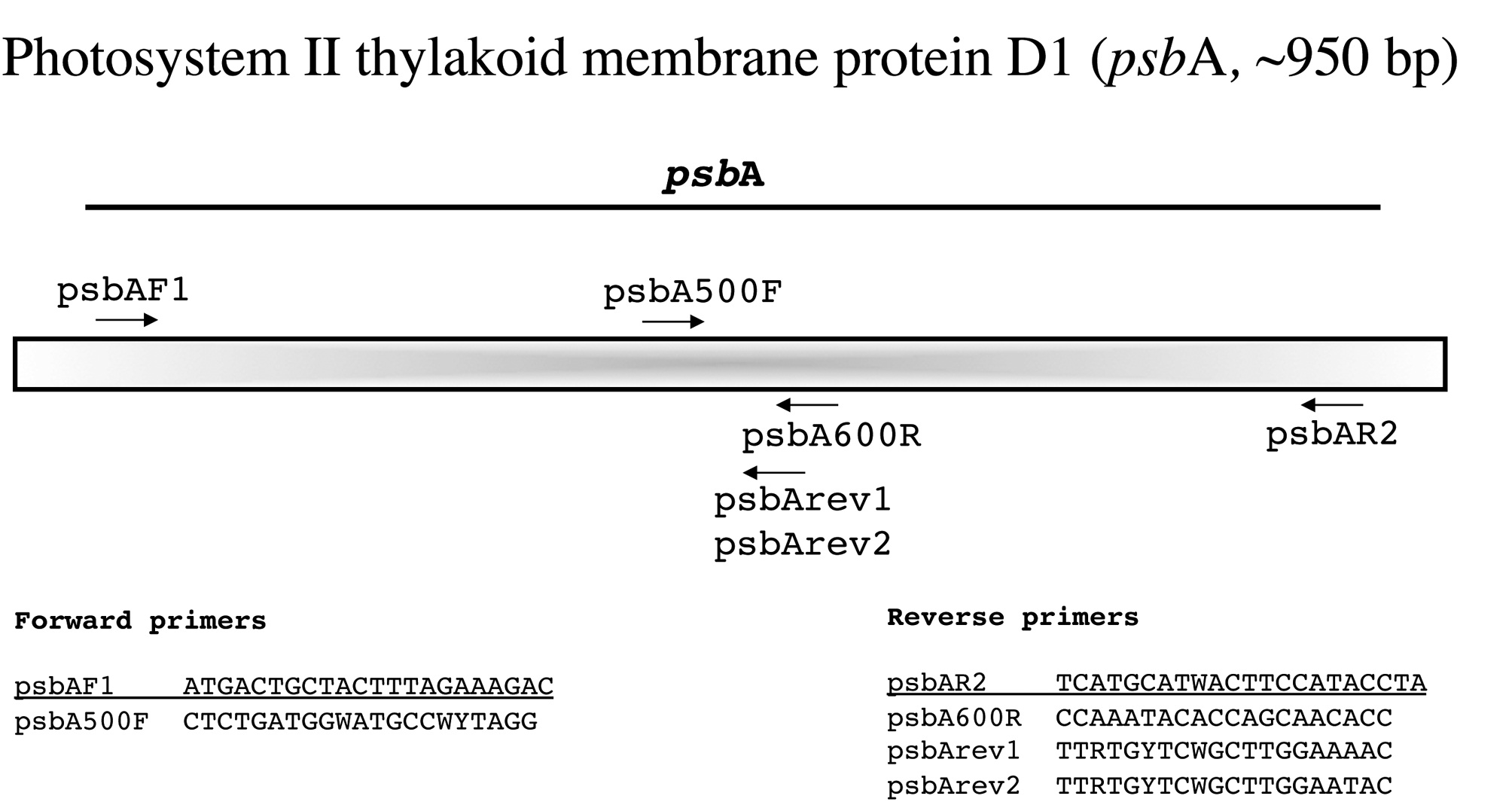

Photosystem II thylakoid membrane protein D1 (psbA, ~950 bp)

This is an easy marker to amplify with the two external PCR primers developed by Yoon et al. (2002) and works broadly among florideophyte algae (Fig. 7). While their (loc. cit.) internal forward sequencing primer psbA500F also works widely, we have had poor sequence for some taxa using the internal reverse primer psbA600R. We thus sequence with external primers first and then pick the best internal reverse option among psbA600R and the newly designed psbArev1 and psbArev2.

Amplification profile: 94℃ for 2 min; 5 cycles of 94℃for 30 s, 45℃ annealing for 30 s, 72℃ extension for 1 min; then 35 cycles of 94℃ for 30 s, 46.5℃ annealing for 30 s, 72℃ extension for 1 min; followed by 72℃ final extension for 7 min.

>

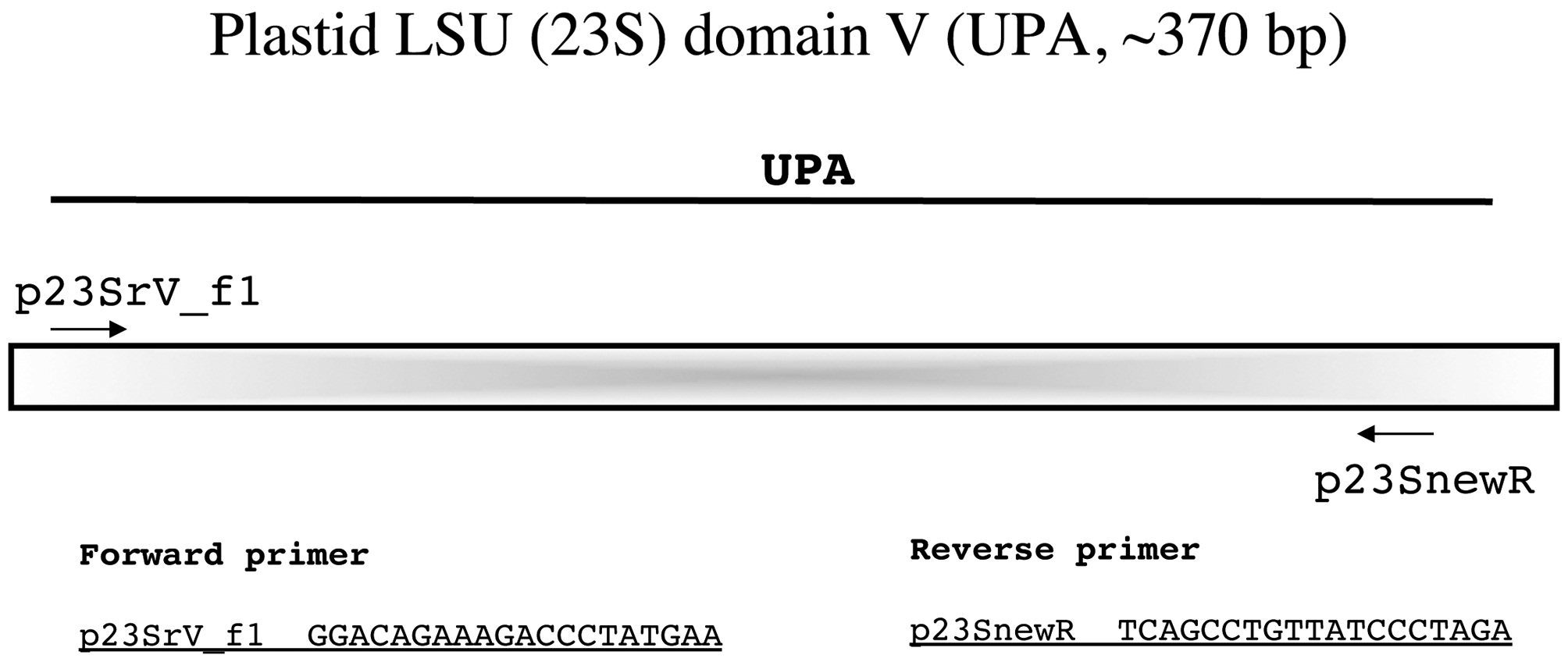

Plastid LSU (23S) domain V (UPA, ~370 bp)

Sherwood and Presting (2007) championed UPA as a universal barcode marker for the algae noting that a single primer pair can reliably recover sequences from a broad taxonomic range including green, red, and brown marine macroalgae, diatoms, and even cyanobacteria. Whereas we have had strong success with their forward primer p23SrV_f1, the reverse primer p23SrV_r1 can result in messy sequence data for some florideophytes. Clarkston and Saunders (2010) reasoned that a repeat near the 3' end of this primer (AGAG) was the cause of this problem and dropped the final nucleotide in designing the modified primer p23SnewR (Fig. 8). We have found this an easily amplified marker from a wide variety of florideophytes with this modification. Being a short marker, no internal primers are necessary to generate full bidirectional reads (Fig. 8).

Amplification profile: 94℃ for 2 min; 35 cycles of 94℃for 20 s, 55℃ annealing for 30 s, 72℃ extension for 30 s; followed by 72℃ final extension for 10 min.

>

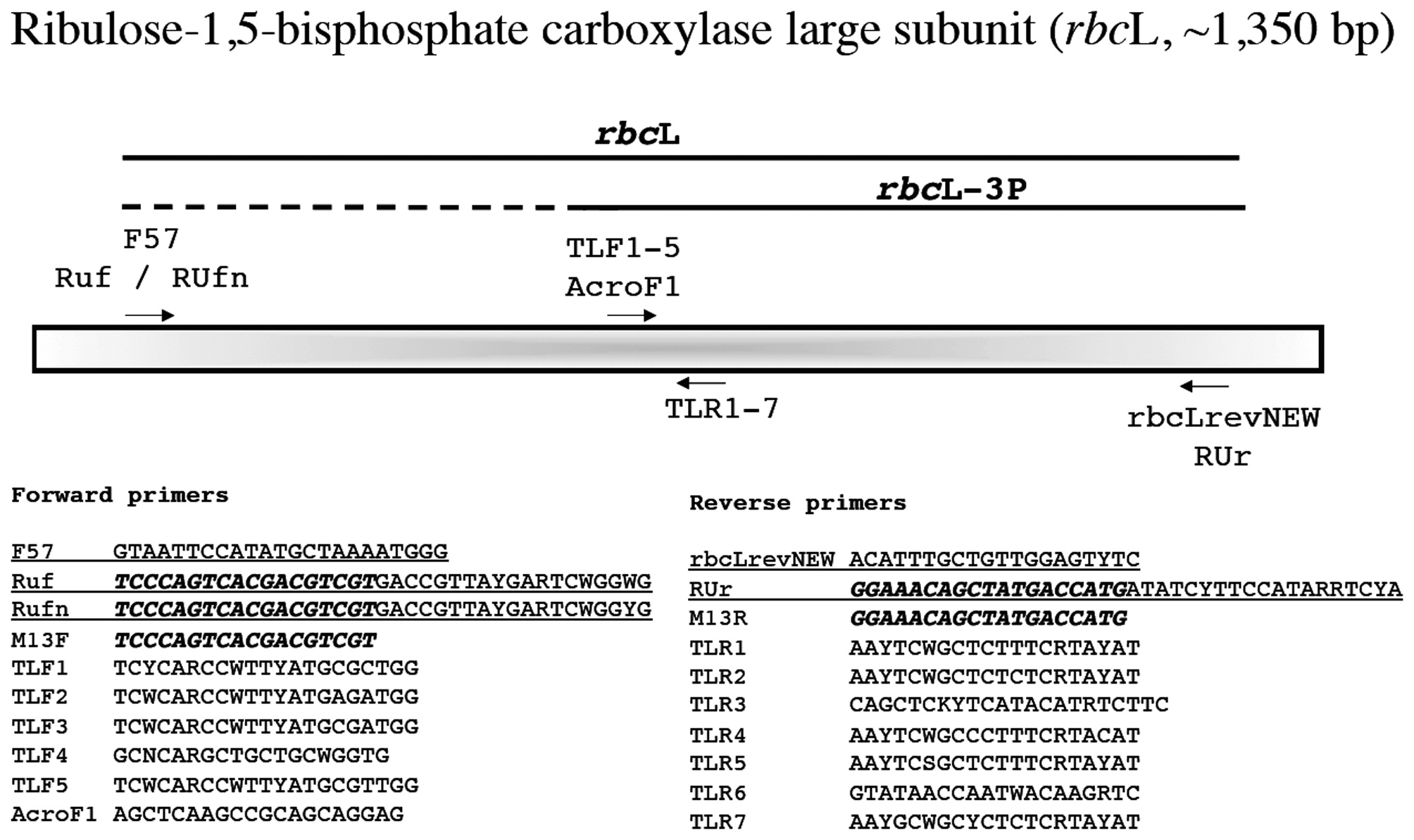

Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase large subunit (rbcL, ~1,350 bp)

This marker is widely used in florideophyte phylogenetic and barcoding studies and was first applied broadly to these algae by Freshwater et al. (1994). We still routinely use the forward PCR primer F57 (Freshwater and Rueness 1994), but also trial the M13-linked Ruf and RUfn for problematic taxa (Fig. 9). These last two primers are linked with one of the available M13 variants (note that the M13 variant here is different from that included below for COI-5P, but either should work; just make sure the M13 variants used for sequencing are a match for those employed in your primer). Thus sequencing employs only the linker portion of the primer when these are used in PCR (Fig. 9). We have also developed an M13 linked reverse primer (RUr), but typically find that our modification of Vis and Sheath’s (1999)

We are using

Amplification profile: 95℃ for 2 min; 35 cycles of 93℃for 1 min, 47℃ annealing for 1 min, 72℃ extension for 2 min; followed by 72℃ final extension for 2 min.

>

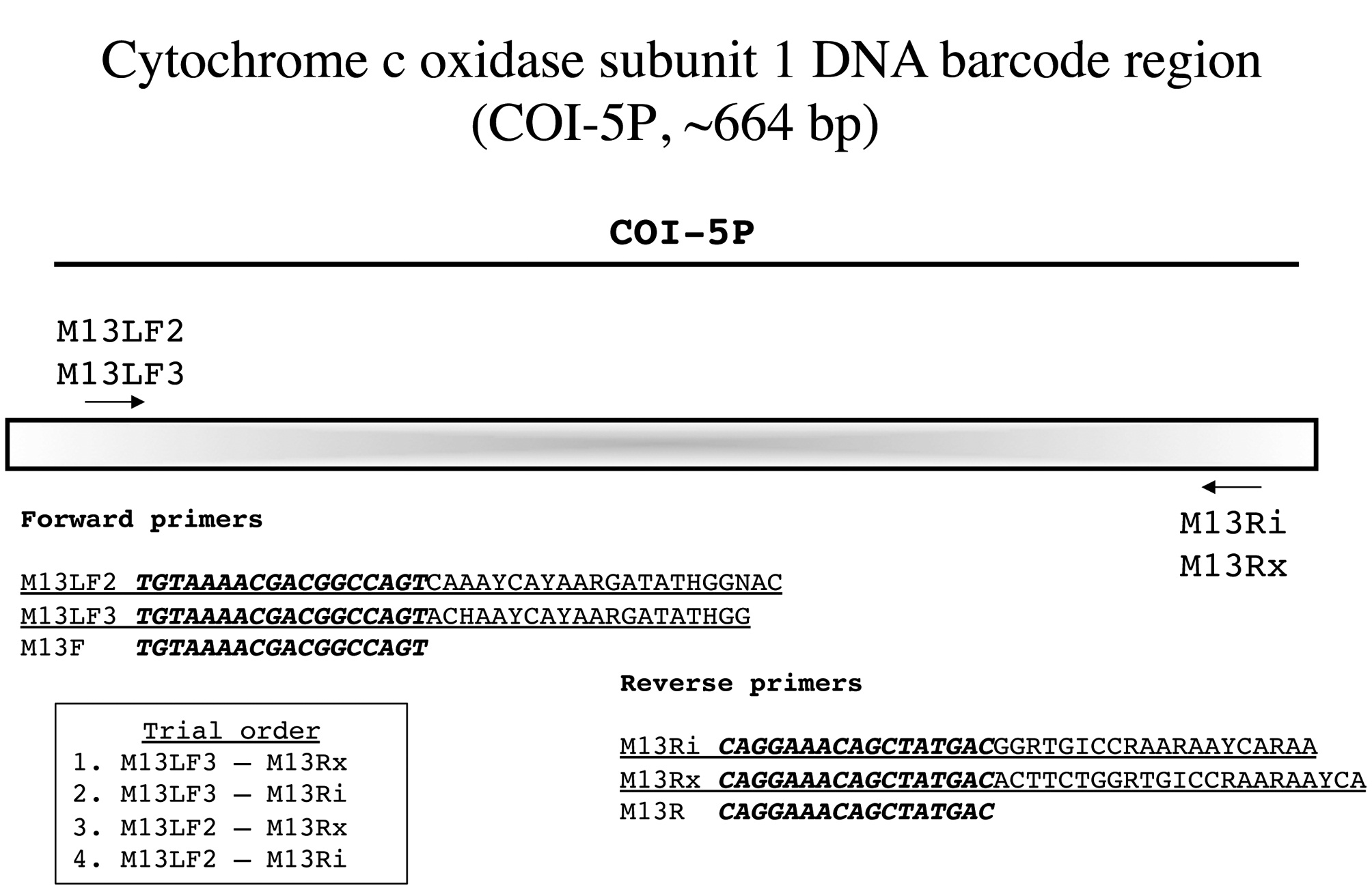

Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 DNA barcode region (COI-5P, ~ 664 bp)

Saunders and McDevit (2012) have recently reviewed the DNA barcode marker COI-5P in detail, but cautioned that primer advances were constantly being developed. So it is that an update is already due, largely improving on their earlier primers by adding variants of M13 linkers to the standard primers (Fig. 10). We now have two forward and two reverse primers that in varied combinations generate PCR product for most red algae. Owing to the short length of this fragment, bidirectional reads are accomplished without the need for internal primers (Fig. 10).

Amplification profile: 94℃ for 2 min; 5 cycles of 94℃ for 30 s, 45℃ annealing for 30 s, 72℃ extension for 1 min;

then 35 cycles of 94℃ for 30 s, 46.5℃ annealing for 30 s, 72℃ extension for 1 min; followed by 72℃ final extension for 7 min.

>

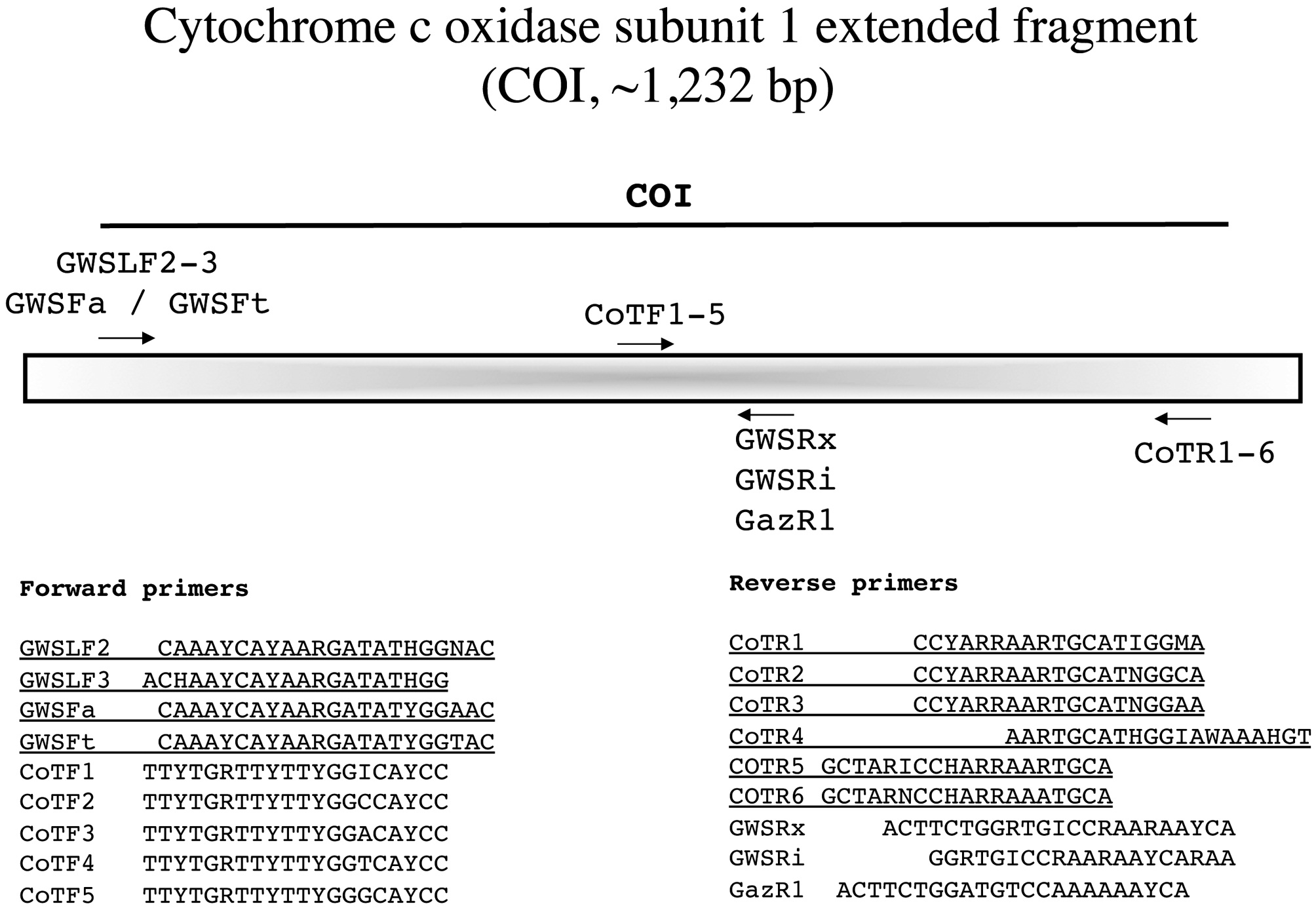

Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 extended fragment (COI, ~1,232 bp)

Saunders (2008) argued that COI-5P had phylogenetic signal for use among closely related taxa and we wanted to expand on this usefulness by generating a larger COI fragment (Fig. 11). Either the external forward M13-linked primers outlined previously (Fig. 10) or the unlinked variants reported with this marker are used in combination with the external reverse primers from the CoTR1-6 series for amplification (Fig. 11). We then sequence with the PCR primers and determine the best internal primers for

sequencing from the forward series CoTF1-5 and among the reverse primers GazR1, GWSRi and GWSRx.

Amplification profile: 94℃ for 4 min; 35 cycles of 94℃for 1 min, 45℃ annealing for 30 s, 72℃ extension for 1 min; followed by 72℃ final extension for 7 min.

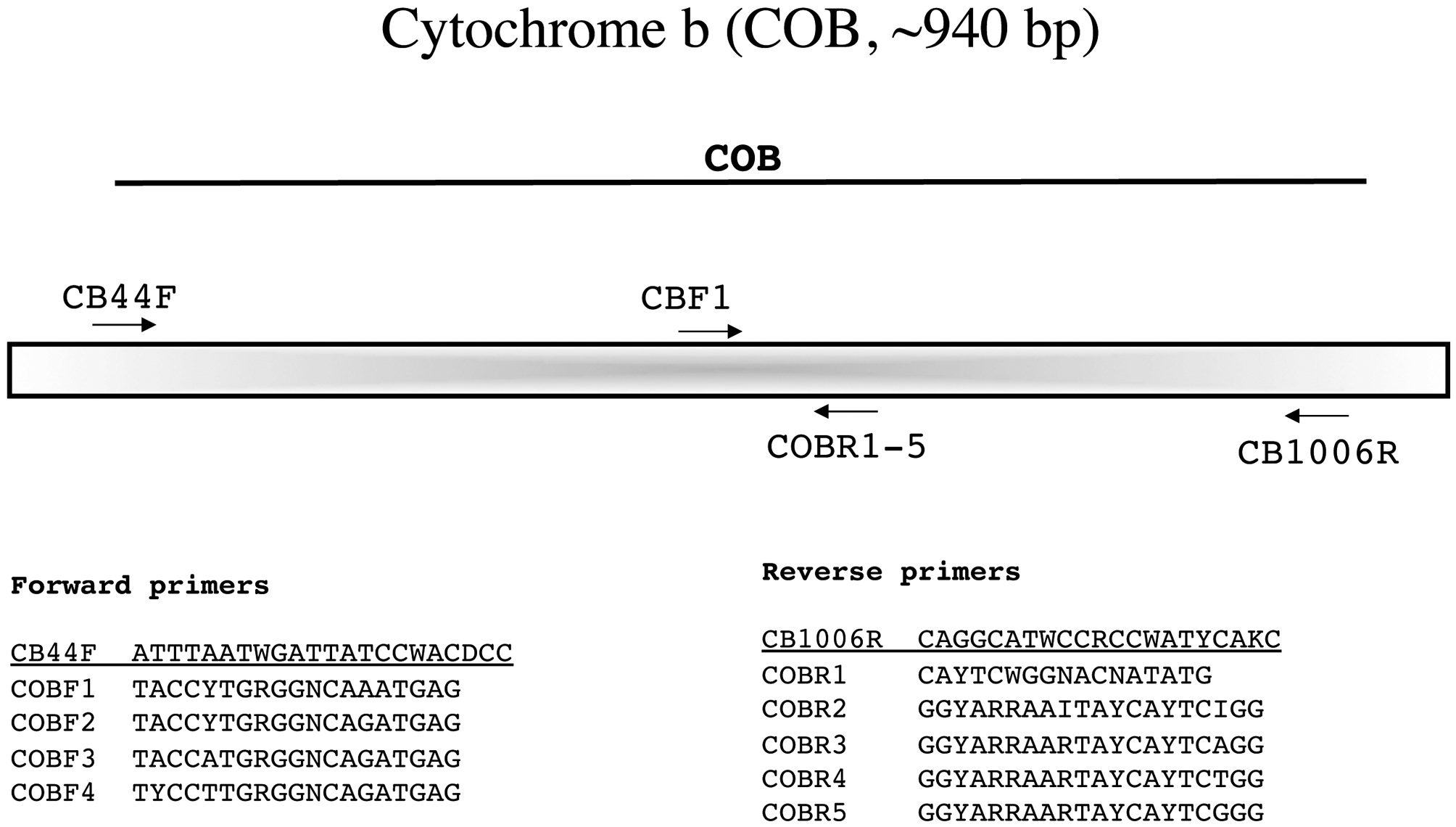

This relative newcomer to red algal studies is amplified with the novel external primers CB44F and CB1006R designed by Ga Hun Boo (laboratory of Prof. Sung Min Boo, a RedToL partner at Chungnam National University, South Korea). Sequence is then generated with these same primers to identify the best internal forward (COBF1-4) and reverse (COBR1-5) sequencing primers (Fig. 12).

Amplification profile: 95℃ for 1 min; 35 cycles of 93℃for 30 s, 42℃ annealing for 30 s, 72℃ extension for 1 min; followed by 72℃ final extension for 7 min.

>

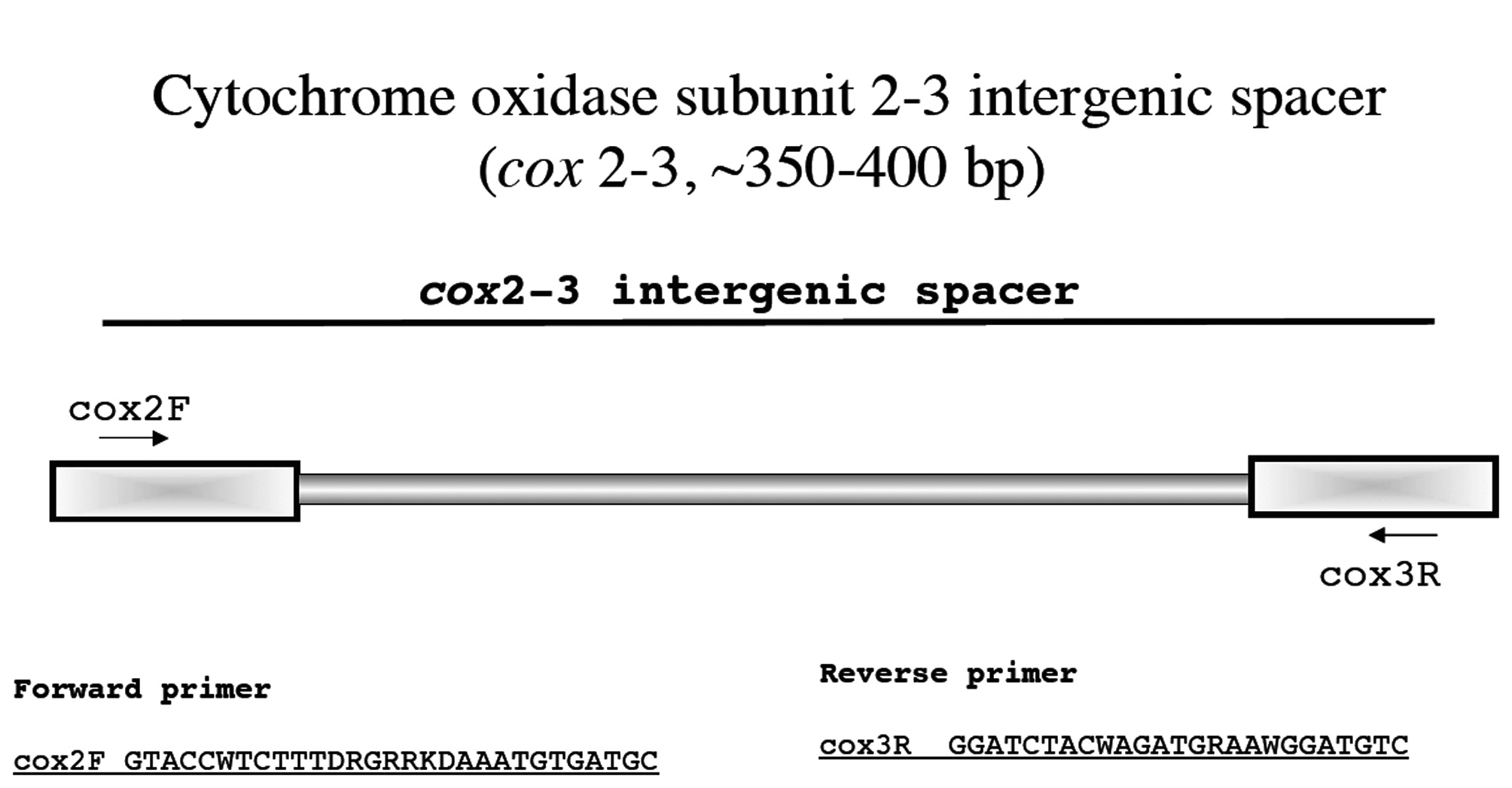

Cytochrome oxidase subunit 2-3 intergenic spacer (cox 2-3, ~350-400 bp)

This marker was first used in red algae by Zuccarello et al. (1999) and is a useful tool at the population level. We have only started to use this system and have not had to develop novel primers to date?so far the original primers of Zuccarello et al. have worked on a broad spectrum of taxa (Fig. 13).

Amplification profile: 94℃ for 2 min; 5 cycles of 93℃for 1 min, 45℃ annealing for 1 min, 72℃ extension for 1 min; then 30 cycles of 93℃ for 30 s, 55℃ annealing for 30 s, 72℃ extension for 30 s; followed by 72℃ final extension for 7 min.

With the current rise in popularity and utility of powerful next generation technologies it is understandable that some of our colleagues may question the usefulness of summarizing single marker amplification protocols. Indeed there are currently three red algal genomes available in GenBank (

A guiding principle for our approach to marker development and use is that primers are affordable and relatively easy to design and / or select once some sequence data are in hand. We thus routinely circumvent contamination and amplification problems by acquiring whatever portion of a marker we can for a specimen. Those data then “inform” our next steps with regards to amplification and or sequencing using primers currently in our lab or newly designed to meet a special need. An example is found in Clayden and Saunders (2010) in which LSU sequences for palmarialean taxa were compared to the host halymeniacean data to facilitate the development of the novel primers rsr1 and rsf1 for use with T01N and T15, respectively (Fig. 3). These primers were then used to amplify this marker as two overlapping fragments for the epi-endophyte

We have extended this philosophy to markers for which relatively conservative external PCR primers have been developed, but for which “universal” internal sequencing primers remain elusive [i.e., EF2 (Fig. 4),

However, one word of caution is necessary whenever markers are amplified as a series of fragments?always be wary of inadvertently generating chimeric sequences (e.g., for the LSU the X and Z fragments may be from your target species, but the Y fragment has amplified from a contaminant on or in the sample). We have encountered chimeric sequences in our own data and those of colleagues between various red and brown algae and have even uncovered mixed alga / invert sequences. This is going to happen, the critical point is to catch it when it does. The problem is obvious in the more variable markers where the fragments have a significant overlap (e.g., EF2 and