Inflammation is a complex process regulated by a cascade of cytokines, growth factors, nitric oxide (NO), and prostaglan-dins (PGs) produced by macrophages. Macrophages are key regulators of the immune response to foreign invaders, such as infectious microorganisms, and are activated by exposure to interferon-γ, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and bacterial li-popolysaccharides (LPSs) (Xie et al., 1993; Zhang and Ghosh, 2000). Activated macrophages play a pivotal role in inflam-matory diseases via excess secretion of cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and other inflammatory mediators such as NO and PGE2 (Vane et al., 1994; Marks-Konczalik et al., 1998). Excessive produc-tion of inflammatory mediators and cytokines is involved in the pathogenesis of chronic diseases, such as atherosclerosis, inflammatory arthritis, and cancer (Libby, 2006; Packard and Libby, 2008; Solinas et al., 2010). Any substances that inhibit production of these molecules are considered as potential anti-inflammatory agents.

Nuclear factor (NF)-κB plays a pivotal role in the early stages of immune and acute phase inflammatory responses, as well as in cell survival (Makarov, 2001; Li and Verma, 2002). NF-κB is usually sequestered in the cytoplasm in an inactive form by the inhibitor of κB (IκB) family. NF-κB activation is associated with increased transcription of genes encoding pro-inflammatory cytokines, adhesion molecules, and enzymes such as inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and cyclooxy-genase-2 (COX-2) (D’Acquisto et al., 1997; Makarov, 2001). Activation of NF-κB induced by LPS involves phosphoryla-tion of IκB-α kinase (IKK), which phosphorylates IκB-α on serines 32 and 36, leading to sequent ubiquitination and deg-radation of IκB-α and translocation of NF-κB into the nucleus (Chen et al., 1995).

Marine algae have been identified as rich sources of struc-turally diverse bioactive compounds with great pharmaceuti-cal potential (Abad et al., 2008; Blunt et al., 2010). A variety of biological compounds, including phlorotannins and fuco-xanthin, were isolated from marine algae and their biological activities characterized (Kim et al., 2005, 2009; Woo et al., 2009).

Dried powder (100 g) of

>

Cell culture and viability assay

Murine macrophage RAW 264.7 (ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA) cells were cultured at 37℃ in Dulbecco’s modified Ea-gle’s medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 units/mL), and streptomycin sulfate (100 μg/mL) under a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cell viability was determined by 3-(4,5-dimeth-yl-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (MTS) assay using a CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were inoculated at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well into 96-well plates and cultured at 37℃ for 24 h. The culture medium was replaced with 200 μL of serial dilutions (0-200 μg/mL) of CFE and the cells incubated for 24 h. The culture medium was re-moved and replaced with 95 μL fresh culture medium and 5 μL MTS solution. After 1 h, the absorbance at 490 nm was measured using a microplate reader (Glomax Multi Detection System, Promega).

>

Measurement of NO, PGE2, and pro-inflammatory cytokines

RAW 264.7 cells were placed in a 12-well plate at a den-sity of 1 × 106 cells per well and incubated for 24 h. Cultured cells were treated with vehicle or various CFE concentrations for 1 h, and then stimulated with 1 μg/mL LPS for 24 h. Cultured media were collected after centrifugation at 2,000 g for 10 min and stored at -70℃ until tested. The nitrite concen-tration in the cultured media was measured as an indicator of NO production. Culture media (100 μL) was mixed with the same volume of Griess reagent (0.1% naphtylethylene di-amine dihydrochloride and 1% sulfanilamide in 5% H3PO4). Absorbance of the mixture at 540 nm was measured with a microplate reader. Levels of PGE2, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in cultured media were quantitated by enzyme-linked immu-nosorbent assay (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) ac-cording to the manufacturer’s instructions.

RAW 264.7 cells were incubated with various CFE con-centrations for 1 h and stimulated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 30 min. CFE-treated or -untreated RAW 264.7 cells were washed twice with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed with lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1% Tween 20, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sul-fate, 50 mM sodium fluoride, 1 mM sodium vanadate, 10 μg/mL leupeptin, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) on ice for 1 h. After centrifugation at 18,000 g for 10 min, the protein concentrations in supernatants were determined, and aliquots of protein (40 μg) were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat dried milk in Tris-buffered saline Tween20 (TBST) for 1 h, followed by incubation for 3 h with primary antibody in TBST containing 5% nonfat dried milk. The blots were treated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugat-ed secondary antibody in TBST containing 5% nonfat dried milk for 1 h, and immune complexes were detected using an ECL detection kit (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA).

>

Transient transfection and luciferase assay

Murine NF-κB promoter/luciferase DNA (1 μg) (Strata-gene, Santa Clara, CA, USA), along with 20 ng control pRL-TK DNA (Promega), was transiently transfected into 2 × 106 RAW 264.7 cells/well in a 12-well plate using Lipofectamine/Plus reagents (Invitrogen) for 24 h. Thereafter, cells were pre-treated with 0-200 μg/mL CFE for 1 h and stimulated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 6 h. Each well was washed twice with cold PBS, harvested in 100 μL of lysis buffer (0.5 mM HEPES, pH 7.8, 1% Triton N-101, 1 mM CaCl2, and 1 mM MgCl2) and used for assessment of luciferase activity using a Dual Lucif-erase assay kit (Promega). Luminescence was measured on a top counter microplate scintillation and luminescence counter in single-photon counting mode for 0.1 min/well, following a 5 min adaptation in the dark. Luciferase activity was normal-ized to the expression of control pRL-TK.

>

Preparation of cytosolic and nuclear extracts

RAW 264.7 cells were treated as described above. After pretreatment with CFE for 1 h and posttreatment with LPS for 30 min, cells were washed twice with cold PBS and collected with 500 μL cold PBS. Cell pellets were resuspended in hypo-tonic buffer (10 mM HEPES/KOH, 10 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and 0.5 mM PMSF, pH 7.9) and orgincubated on ice for 15 min. After vortexing for 10 s, homog-enates were divided into supernatants (cytoplasmic compart-ments) and pellets (nuclear components) by centrifugation at 13,000 g for 10 min. The pellet was gently resuspended in 40 μL complete lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES/KOH, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 300 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, and 0.5 mM PMSF, pH 7.9) and centrifuged at 13,000 g for 20 min at 4℃. The supernatant was used as the nuclear extract.

To analyze nuclear localization of NF-κB in RAW 264.7 cells, cells were maintained on glass coverslips (SPL Life-sciences Co., Gyeonggi-do, Korea) in 24-well plates for 24 h. After stimulation with CFE and/or LPS (1 μg/mL), cells were fixed in 4.0% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min at room temperature, then permeabilized with 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min. Permeabilized cells were washed with PBS and blocked with 3% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) in PBS for 30 min. Thereafter, cells were incubated in an anti-NF-κB/p65 polyclonal antibody diluted in 3% BSA/PBS for 2 h, rinsed three times for 5 min with PBS, and incubated in Al-exa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody diluted in 3% BSA/PBS for 1 h. Cells were on mounted with 2 μg/mL DAPI and viewed, and images were captured using an LSM700 la-ser scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Data were expressed as the means ± SDs. Data were analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Student’s

>

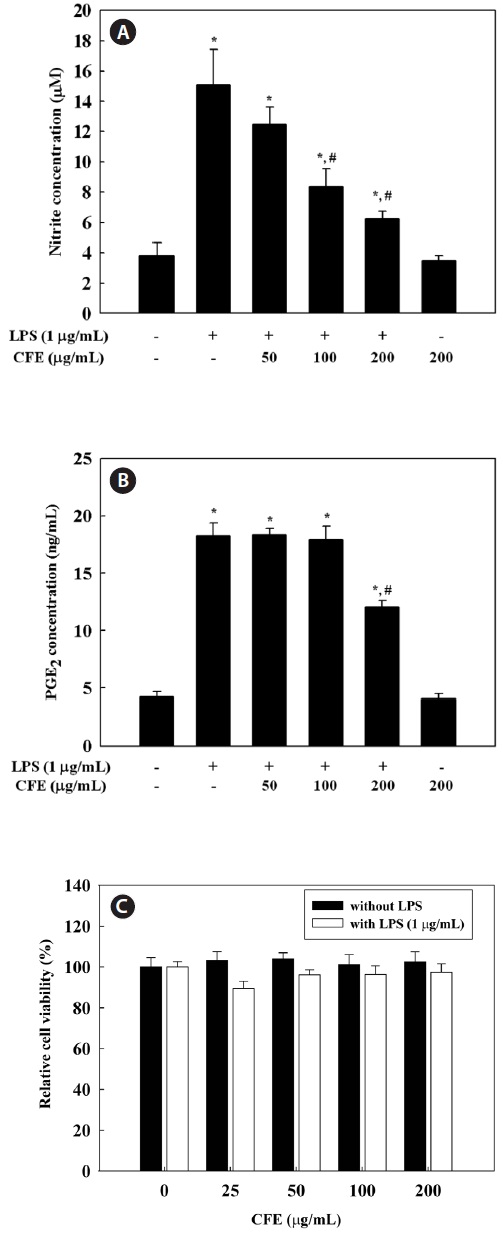

CFE inhibits NO and PGE2 production in LPS-stimulated cells

To evaluate the effect of CFE on NO production in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells, we measured nitrite concentra-tions in culture media using the Griess reagent. RAW 264.7 cells were pretreated with 50-200 μg/mL CFE for 1 h and stimulated with LPS for 24 h. NO production, measured as ni-trite, was increased by LPS alone; however, CFE significantly reduced NO levels in LPS-stimulated cells in a dose-depen-dent manner (Fig. 1A). To determine the effect of CFE on PGE2 production in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells, PGE2 concentrations in culture media were determined by ELISA.

PGE2 production by RAW 264.7 cells was increased by LPS treatment, although 200 μg/mL CFE suppressed the produc-tion of PGE2 in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. To exclude the possibility that the decreased NO and PGE2 levels were due to cell death, we determined the effect of various CFE concentrations on cell viability. The MTS assay demonstrated that CFE showed no cytotoxicity in RAW 264.7 cells up to 200 μg/mL (Fig. 1C). Thus, the inhibitory effects of CFE on NO and PGE2 production were not due to cytotoxicity. Thus, CFE significantly inhibited NO and PGE2 production by LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells.

>

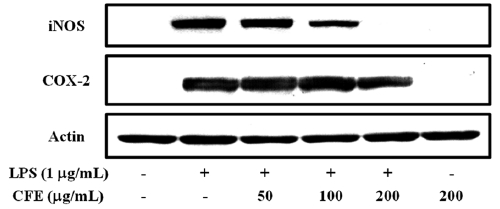

CFE inhibits the expression of iNOS and COX-2 in LPS-stimulated cells

Since iNOS and COX-2 are the key enzymes for the pro-duction of NO and PGE2, respectively, we analyzed the ex-pression iNOS and COX-2 proteins in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells by Western blotting. As shown in Fig. 2, CFE strongly inhibited the expression of iNOS in a dose-dependent manner; however, inhibition of COX-2 expression occurred at 200 μg/mL CFE, similar to the suppression of PGE2 produc-tion (Fig. 1B). These results suggest that the CFE-mediated inhibition of NO and PGE2 production in LPS-stimulated macrophages is associated with downregulation of iNOS and COX-2 expression.

>

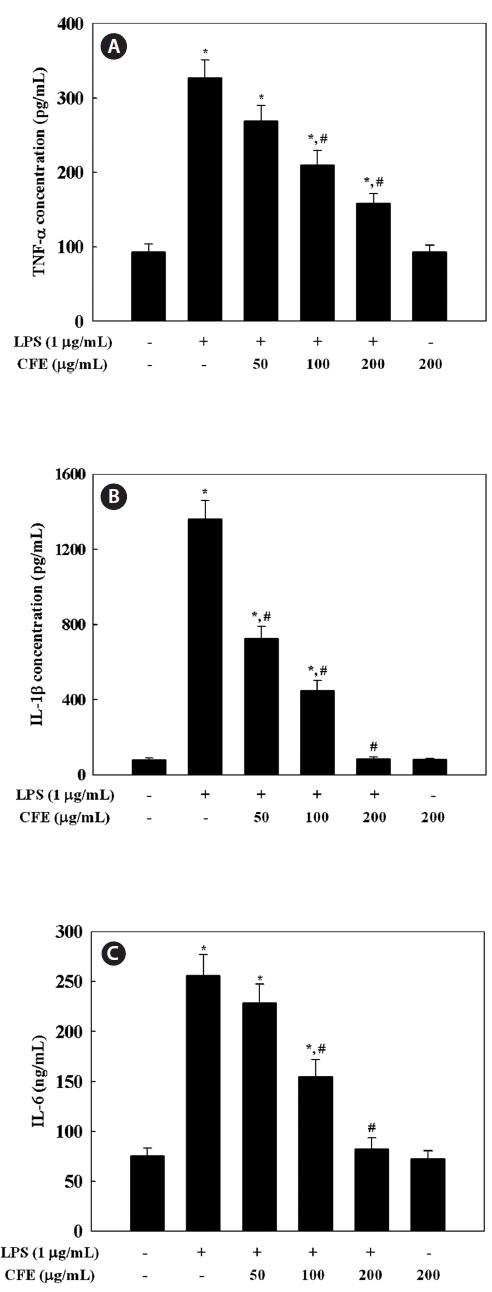

CFE inhibits production of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in LPS-stimulated cells

Since CFE was found to inhibit the expression of NO and PGE2 in a dose-dependent manner, we investigated the effect of CFE on production of pro-inflammatory cytokines by LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells, including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 by ELISA. Stimulation of RAW 264.7 cells with LPS led to significantly increased levels of TNF-α (Fig. 3A), IL-1β (Fig. 3B), and IL-6 (Fig. 3C). However, pro-inflammatory

cytokine production in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner by exposure to 50-200 μg/mL CFE (Fig. 3). The inhibitory effect of CFE on TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 production was not due to cytotoxicity, since cell viability was not altered by CFE at the concentrations used (Fig. 1C). This result indicates that CFE significantly suppressed LPS-induced TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 production, which supports the hypothesis that CFE inhibits the initial phase of the LPS-stimulated inflammatory response.

>

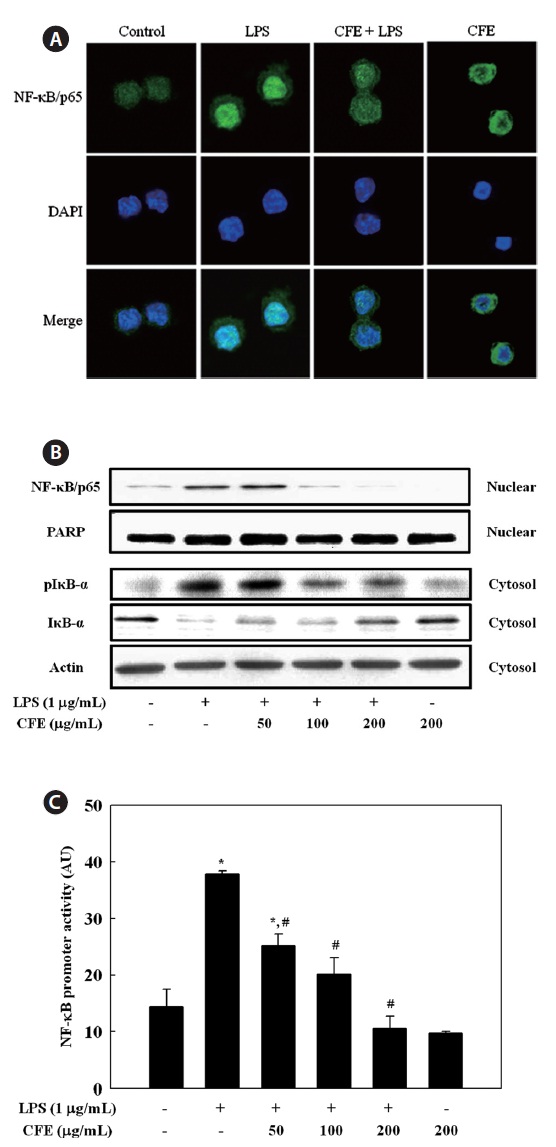

CFE inhibits NF-κB activation in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells

We then investigated whether CFE could inhibit the trans-location of the NF-κB/p65 subunit from the cytosol to the nucleus in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. Immunofluores-cence revealed that, in unstimulated cells, NF-κB/p65 was dis-tributed mostly in the cytoplasm. After stimulation with LPS, most cytoplasmic NF-κB/p65 was translocated to the nucleus, as shown by strong NF-κB/p65 staining in the nucleus (Fig. 4A). The level of NF-κB/p65 in the nucleus was markedly reduced by pretreatment with CFE. To assess the molecular mechanisms underlying translocation of NF-κB from the cyto-sol to the nucleus in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells, we also investigated the inhibitory effect of CFE on LPS-stimulated degradation of IκB-α, which is responsible for the activation of NF-κB, by Western blotting. LPS treatment resulted in in-creased IκB-α degradation compared to controls, and CFE pretreatment recovered the level of cytosolic IκB-α in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4B). As a result of IκB-α degradation, the increased nuclear NF-κB/p65 level after LPS stimulation was reduced by CFE pretreatment in a dose-dependent man-ner (Fig. 4B). Considering the inhibitory effects of CFE on LPS-induced NF-κB activation, we next determined the effect of CFE on the promoter activity of NF-κB in LPS-stimulated macrophage cells. For this, cells were transiently transfected with luciferase DNA containing murine NF-κB promoter, and the transfected cells were then pretreated for 1 h with various CFE concentrations, followed by LPS treatment for 6 h. Data suggested that CFE treatment significantly inhibited LPS-induced NF-κB promoter-driven luciferase expression in macrophages (Fig. 4C). These results indicate that the CFE-mediated inhibition of iNOS, COX-2, and pro-inflammatory cytokine expression levels was regulated by the NF-κB path-way in LPS-stimulated macrophages.

We investigated the biological effects of CFE on produc-tion of inflammatory mediators in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophage cells. To further clarify the molecular mecha-nisms underlying the effect of CFE, we determined the effects of CFE on the production of NO, PGE2, TNF-α, IL-1β,

and IL-6, the expression of iNOS and COX-2 protein, and the activation of NF-κB. Data suggested that CFE effectively in-hibited the production of NO, PGE2, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 through downregulation of NF-κB activity. The inhibitory ef-fect of CFE on inflammatory mediator expression suggests a mechanism responsible for its anti-inflammatory action and its potential for use as a therapeutic or nutraceutical agent for inflammatory diseases.

NO is synthesized from ?-arginine and molecular oxygen by the action of NOS. Under pathological conditions, a sig-nificant increase in NO synthesis by iNOS participates in provoking inflammatory process and acts synergistically with other inflammatory mediators (Nathan, 1992). Also, iNOS is strongly stimulated upon exposure to bacterial endotoxin or pro-inflammatory cytokines (Guha and Mackman, 2001). Compounds capable of reducing NO production or iNOS ac-tivity may be attractive as anti-inflammatory agents, and for this reason, the suppressive effects of natural marine com-pounds on NO production have been intensively studied to develop anti-inflammatory drugs (Abad et al., 2008; Jung et al., 2009; Heo et al., 2010; Jin et al., 2010; Kim and Kim, 2010). COXs regulate the conversion of arachidonic acid to PGE2 and are rate-limiting enzymes in the biosynthesis of PGs. COX-1 is constitutively expressed in many tissues, while COX-2 is an inducible enzyme that produces, in most cases, large quantities of PGs. COX-2 is highly expressed in inflammation-related cell types, including macrophages and mast cells, after stimulation by pro-inflammatory cytokines and/or LPS (Nathan, 1992; Vane et al., 1994). Recent stud-ies have shown that

Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, are small secreted proteins that regulate immunity and in-flammation. Bacterial LPS stimulates macrophages to release TNF-α, and the secreted TNF-α or LPS then induces release of IL-1β and IL-6 (Beutler and Cerami, 1989). TNF-α induces several physiological effects, including septic shock, inflam-mation, and cytotoxicity (Dinarello, 1999). IL-1β is a major pro-inflammatory cytokine that is produced mainly by macro-phages and is believed to play a significant role in the patho-physiology of endometriosis (Lebovic et al., 2000). More-over, IL-1β is important for the initiation and enhancement of the inflammatory response to microbial infection (Kim and Moudgil, 2008). IL-6 is also a pivotal pro-inflammatory cy-tokine synthesized mainly by macrophages; it plays a role in the acute-phase immune response (Yoshimura, 2006) and is regarded as an endogenous mediator of LPS-induced fever. Our data indicate that CFE significantly suppressed LPS-stimulated TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 secretion, which supports the hypothesis that CFE inhibits the initial phase of a LPS-stimulated inflammatory response.

The induction of inflammatory mediators, such as NO and PGE2, and pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, is dependent on NF-κB activation (Li and Verma, 2002). NF-κB plays a pivotal role in the regulation of cell survival genes and coordinates the expression of pro-inflammatory enzymes and cytokines, such as iNOS, COX-2, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 (Xie et al., 1993; D’Acquisto et al., 1997; Marks-Konczalik et al., 1998; Makarov, 2001). NF-κB is associated with an inhibitory subunit, IκB, which is pres-ent in the cytoplasm in an inactive form. Activation of NF-κB induced by LPS or pro-inflammatory cytokines leads to the phosphorylation of IKK, which then phosphorylates IκB-α on serines 32 and 36, leading to subsequent degradation of IκB-α and inducing translocation of NF-κB into the nucleus (Chen et al., 1995). In this study, we observed that downregulation of IκB-α by LPS was recovered by CFE treatment, suggesting that CFE protected the proteolytic degradation of IκB-α. Deg-radation of IκB-α involves its dissociation from the inactive complex, leading to activation of NF-κB in response to LPS. Moreover, using immunofluorescence, we found that nuclear translocation of NF-κB was significantly inhibited by CFE, supporting the inhibition of IκB-α degradation by CFE. From these data, the CFE-mediated downregulation of LPS-induced iNOS, COX-2, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 expression in RAW 264.7 cells is most likely largely associated with the ability of CFE to inhibit the NF-κB pathway. This is, to our knowledge, the first report addressing the negative regulation by CFE of the NF-κB pathway in response to LPS.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that CFE inhibited the pro-duction of inflammatory mediators, such as NO and PGE2, and pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages. Moreover, the inhibitory effect of CFE was associated with inactivation of the NF-κB pathway via blocking IκB degradation. Confirmation of the anti-inflammatory activity of CFE and the mechanism underlying its effects contributes to the further application of CFE in functional food for inflammation-mediated diseases. These results suggest to us additional studies with the aim of determining the compound(s) within CFE that contribute to its anti-inflammatory activity.