Oyster is an important bivalve species in the shellfish indus-try in Korea due to its high nutritional value and good taste. However, many reports have indicated their deterioration in quality including taste. Also the quality varies depending on the cultivation conditions, such as the quantity or species of feed planktons or water quality. Color changes in oysters, such as greening (Kimura, 1969) and red (Hata et al., 1982) and yellowish (Hata et al., 1987) coloration, are presumed to originate from feed plankton. Also, Hatano et al. (1990) re-ported an unacceptable taste and coloration of oysters in Ja-pan. Moreover, Parry et al. (1989) reported the bitter taste of cultured oysters during a bloom of the diatom,

In Korea, Lee (1995) first reported bitter-tasting oysters cul-tured in Gamak Bay on the southern coast between November 1989 and January 1990. Smoked and boiled-canned oysters produced by using the oysters collected at the same location also tasted bitter. Although no report of illness followed the consumption of these bitter oysters, the taste seriously dam-aged the local oyster industry. The incident prompted us to elucidate the structure of the bitter compound. From oysters collected during that event, five bitter tasting compounds with peptidic natures tentatively named gamakamides A-E (derived from the name of Gamak Bay), were isolated (Lee, 1995). We aimed to report the structure of gamakamide-E .

Bitter-tasting oyster

The nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were mea-sured using a JEOL GSX-400 (Jeol, Tokyo, Japan), and Var-ian Unity INOVA 600 (Palo Anto, CA, USA) in D2O, CD3CN and CD3OD. High-resolution (HR) and low-resolution fast atom bombardment mass spectrometry (FAB-MS) spectra were measured with a JEOL JMS 303HF spectrometer (Jeol, Tokyo, Japan) and JEOL JMS 700 spectrometer (Jeol). Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) spectra were measured with a Finnigan Mat TSQ-700 spectrometer (San Jose, CA, USA). Circular dichroism (CD) spectra were re-corded on a JASCO J-720 spectropolarimeter (Jasco, Tokyo, Japan). Optical rotations were measured with a DIP-370 spec-trometer (Jasco).

Frozen raw (1 kg), smoked-canned (10 kg) and boiled-canned (17 kg) oysters were extracted with acetone three times. After evaporating off the acetone, the extract was parti-tioned between MeOH-H2O (8:2) and hexane. A bitter residue obtained in the MeOH-H2O (8:2) layer was next partitioned between CHCl3 and H2O. The organic fraction was evaporat-ed, dissolved in CHCl3-MeOH (1:1), and passed through an alumina column (ICN Biomedicals, Seven Hills, NSE, Austra-lia). The column was washed with CHCl3-MeOH (1:1) and the bitter compound was eluted with 1% NH4OH-MeOH (1:1). The residue was chromatographed on a silica gel column (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) with CHCl3, CHCl3-MeOH (9:1) and CHCl3-MeOH (1:1) and the bitter compound was detected in the second eluate. The bitter substances were fur-ther purified on a Toyopearl HW-40 column (Toso, Tokyo, Ja-pan) with MeOH-H2O (7:3), The constituents were dissolved in MeCN-H2O (45:55) and passed through a Fuji Gel ODS column (Fuji Chemical, Tokyo, Japan) with the same solvent. Further high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) pu-rification was performed on a Develosil ODS-7 column (10 × 250 mm; Nomura Chemicals, Tokyo, Japan) with MeCN-H2O (45:55) and on an Asahipak ODP-50 column (0.8 × 250 mm; Showa Denko, Tokyo, Japan) with MeCN-H2O (45:55, yield: 0.0002% against to the raw oyster).

>

Acid hydrolysis and Marfey analysis

Purified gamakamide-E (0.1 mg) was hydrolyzed with 6 N HCl in an evacuated tube by heating at 110℃ for 26 h. After cooling to room temperature, the reaction mixture was evaporated at 50℃

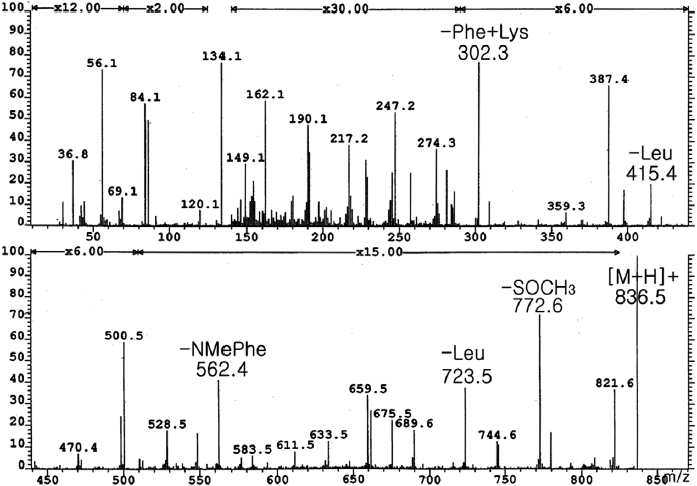

From frozen and canned oysters, gamakamide-E was iso-lated as a colorless amorphous solid ([α]D20 -77.8° [c 0.036, CH3OH]) after several chromatography steps (Lee, 1995). Amino acid analysis revealed two units of leucine (Leu) and one methionine (Met). The positive ion FAB MS/MS of ga-makamide-E (Fig. 1) gave a molecular ion peak [M + H]+ at

Conversion of L-Met(O) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) to L-Met by acid hydrolysis was confirmed by ESI MS and HPLC. Therefore, the existence of Met(O) in the molecule was confirmed. The molecular formula of C43H61N7O8S was deduced from HR FAB-MS ([M + H]+

>

Planar structure of gamakamide-E

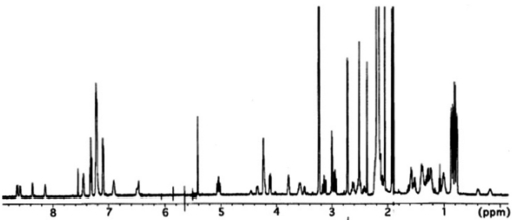

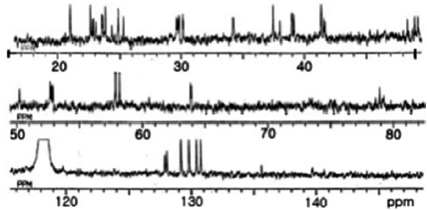

Analysis of 2D NMR spectra, COSY, TOCSY, HSQC and heteronuclear multiple bond correlation (HMBC), allowed the complete assignment of these three amino acids as well as the assignment of signals for

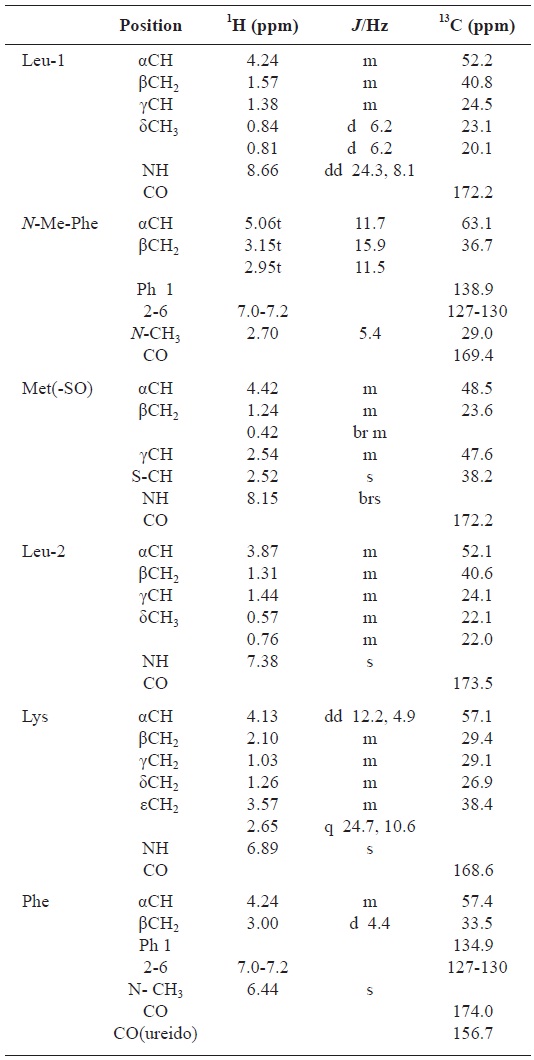

This ratio was unaffected by temperature alteration, indi-cating that the two sets of signals did not arise from confor-mational changes, but from stereoisomers of sulfoxide in Met (O). In the 13C NMR spectrum (Fig. 3), a ureido carbon was detected at 156.7 ppm. The remaining of 42 carbons were as-signed to the amino acid residues.

All these data about the 1H NMR and 13C NMR summarized on the Table 1.

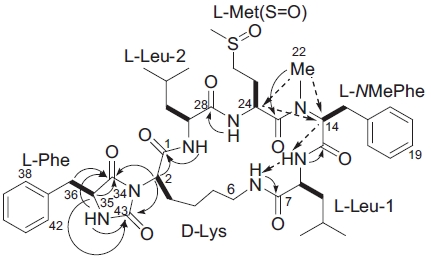

Sequencing of amino acids was mainly accomplished by

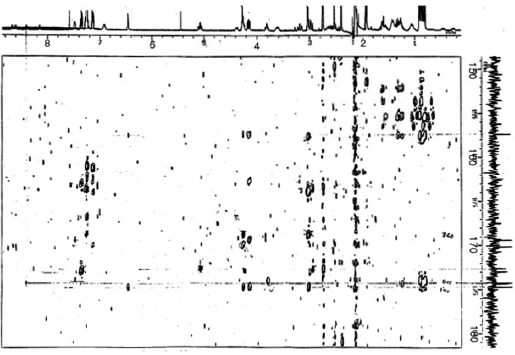

HMBC experiments (Fig. 4). Correlations between NH pro-tons and the

[Table 1.] Assignment of 1H and 13C NMR spectra for gamakamide-E (600 MHz, CD3CN)

Assignment of 1H and 13C NMR spectra for gamakamide-E (600 MHz, CD3CN)

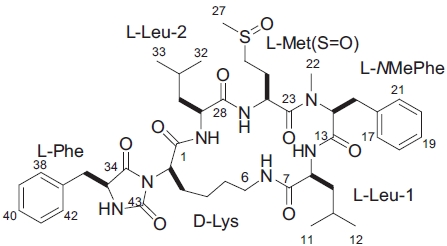

In the ROESY spectrum, NOE correlations among 8-NH/6-NH, 8-NH/H14, 24-NH/H29, and H14/H24 supported the amino acids sequence (Fig. 5). A hydantoin (Hy) structure was also determined by HMBC experiment. Correlations from the α-proton of Lys to both the carbonyl carbon of Phe and the ureido carbon, and from both α- and NH protons of Phe to the ureido carbon were observed. Based on these data, the planar structure of gamakamide-E was deduced (Fig. 6).

>

Stereochemistry of gamakamide-E

Acid hydrolysis of gamakamide-E, derivatization of the resultant amino acids with Marfey's reagent (Marfey, 1984), and subsequent HPLC analysis demonstrated L-stereochem-istry of Met(O),

Gamakamide-E was neither lethal to mice (100 μg/20 g mice ip) nor inhibited the growth of