Manipulation of growth traits through growth hormone (GH)-transgenesis has received a lot of attention as a potential means of overcoming the drawbacks of traditional selective breeding of farmed fishes despite the numerous ecological risks associated with GH-transgenic geno- and phenotypes that remain to be addressed (Devlin et al., 2006; Nam et al., 2007). Early research in fish GH-transgenesis has largely fo-cused on the use of genetic elements of non-piscine origins (

Over the past decade, many researchers have suggested that homologous gene constructs are more effective than distantly heterologous ones for GH-transgenesis in fish (Zbikowska, 2003). The effectiveness of GH-transgenesis using completely homologous genetic elements for both the promoter and struc-tural gene (

Common carp

>

Generation of autotransgenic common carp and early viability assessment

To construct the GH-transgene, a 2.5-kb portion of the com-mon carp β-actin regulatory region, including the non-trans-lated exon I and intron I, was spliced upstream of the 2.1-kb carp growth hormone genomic gene (pcaβ-actGH). Linearized pcaβ-actGH resuspended in 0.1 mM Tris-Cl at a concentra-tion of 100 μg/mL was microinjected into one-celled embryos obtained from artificial fertilization. Injected embryos were maintained in an incubator at 25℃ until hatching. Approxi-mately 1,800 embryos were injected and a similar number of non-injected embryos were prepared for the control sibling group. Hatching success and early survival rate were esti-mated with 55 randomly chosen embryos in triplicate. After hatching, larvae from the injected and non-injected groups were reared in 50-L recirculating tanks. Fish were fed artifi-cial carp feed (40% crude protein). At 2 weeks post-hatching, fish were transferred to two separate 120-L tanks and further grown to 50 days postfertilization for PCR screening of the transgene. During this period, early viability was estimated weekly for both microinjected and non-injected groups.

At 50 days postfertilization, caudal fin tissue (~50 mg) was obtained from each putative transgenic individual that was heavier than the average individual from the non-injected con-trol group. Genomic DNA was prepared using a conventional soduim dodecyl sulfate/proteinase K method followed by or-ganic extraction and ethanol precipitation (Nam et al., 2001). A 1-μg aliquot of purified DNA served as a template for PCR amplification of the transgene using a pair of primers specific to either the β-actin regulator (caβ-actF: 5´-ACATGGTCA-CATGCTCACTG-3´) or the GH gene (caGHR: 5´-ACACCT-GCACCAGCTGGCTG-3´). The thermal cycling conditions were as follows: 33 cycles at 94℃ for 45 s, 60℃ for 45 s, and 72℃ for 1 min, with an initial denaturation step at 94℃ for 3 min and a final elongation step at 72℃ for 5 min. Fish that were PCR-positive for the construct were selected for further examination of their growth performance until sexual matu-rity. For the non-transgenic group, representative individuals whose body weights were closest to the average body weight of the control group were selected.

>

Growth trial of founder generation transgenic fish

Communal rearing was carried out to examine the differen-tial growth rates between GH-transgenic and non-transgenic carp under the same culture conditions. Selected transgenics (

>

Germ-line transmission of the transgene and early growth of the F1 generation

Nine-month-old transgenic males (

Percent hatching success (percentage of eggs injected) and early survival up to yolk sac absorption (percentage of hatched larvae) of the microinjected groups as determined from 55 randomly chosen embryos were 36 ± 3% and 69 ± 4%, respec-tively. Both of these values were significantly lower than those of the non-injected control embryos (80 ± 5% for hatching and 78 ± 4%;

At 50 days postfertilization, the presence of the transgene in presumed transgenic founders differed substantially accord-ing to body-size classes when assessed by PCR screening. In the small-sized group (body weight range, 0.1 to 10.0 g), the frequency of individuals harboring the pcaβ-actGH construct was 9.8% (five PCR-positive individuals of the 51 fish test-ed). Notably, only 3.5% of the medium-sized group (range, 10.1 to 25.0 g) showed the transgene (10 of 287 individuals). Conversely, the large-sized group (heavier than 25.1 g) exhib-ited a significantly higher transgene incidence (55.7%; 54 of 97 individuals) than the other two groups. Moreover, several PCR-positive individuals identified from the large-sized group exhibited extraordinarily heavy body weights that clearly de-viated from the normal distribution of body weights in the non-injected group. Specifically, some transgenic fish belong-ing to the largest size class weighed more than 140 g, which is at least 6-7 times heavier than the average body weight of the non-injected group (20.8 ± 3.5 g). These data suggest that the early growth of this species was highly responsive to transgenesis with the pcaβ-actGH construct. Note, how-ever, that several presumed founder fish showing quite low weights were clearly PCR-positive for the construct, while approximately 7% of the large-sized fish were PCR-negative. Detection of the transgene in such slow-growing fingerlings could be explained by an inhibitory effect resulting from the

overexpression of GH during early development (Devlin et al., 1995; Nam et al., 2002). The relatively high frequency of small-sized PCR-positive fingerlings showing abnormal morphologies may support this hypothesis (photograph not shown). Another plausible but unproven assumption is that the transgene integrated into a specific site within the host genome that resulted in an undesirable position effect (Maclean et al., 1987; Hackett and Alvarez, 2000). Detailed evaluations of the transgenic status of these fish, particularly focusing on trans-gene copies and integration sites, are required to test these hy-potheses. Conversely, the occurrence of PCR-negative fish in the large-sized group could be explained by either a mosaic distribution of the transgene across tissues or an extremely high level of mosaicism in the fin tissues that were chosen for PCR screening. Genetic mosaics are often reported to result from microinjected embryos (Nam et al., 2007).

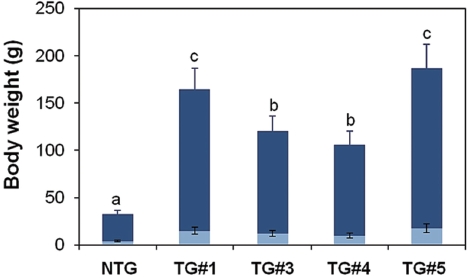

The growth trial during which fish were communally reared in the same tank revealed very interesting results (Fig. 1). Transgenic founders still exhibited extensive variation in body weights. On average, transgenics surpassed their non-transgenic siblings at as early as 2 months of age. The dif-ferences between these groups increased greatly with age. By 4 months, the transgenic group exhibited an average body weight of 1.6 kg, which was 12-fold that of the communally grown non-transgenic group (126 g). This difference was even more pronounced at 6 months, at which point the transgenic group showed an average body weight of 4.1 kg, while that of the non-transgenic group was 286 g. Many transgenic carp individuals exceeded 5 kg in body mass at 8 months of age, al-though several transgenic founders showed no further growth acceleration during this phase, possibly due to suboptimum culture conditions. Both the transgenic and non-transgenic

groups showed greater than 80% survival during the commu-nal tank growth trial. These data suggested that the growth traits of this species could be engineered through an autotrans-genic manipulation without any significant adverse effects on viability. Furthermore, the present GH-autotransgenesis was much more effective toward the growth response in carp than previous attempts at transgenesis using heterologous transgene constructs (Fu et al., 2005). Nevertheless, this pilot examination should be followed by further efforts to address many remaining issues associated with growth performances and other production characteristics. Such experiments should include examinations of growth performance under more re-alistic culture conditions (

Germ-line transmission of growth hormone transgene from founder autotransgenic carp males to F1 progeny

observed in an autotransgenic mud loach (Nam et al., 2001).

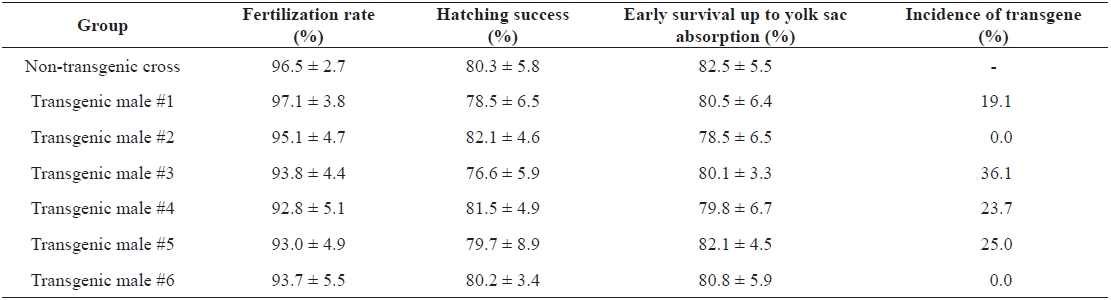

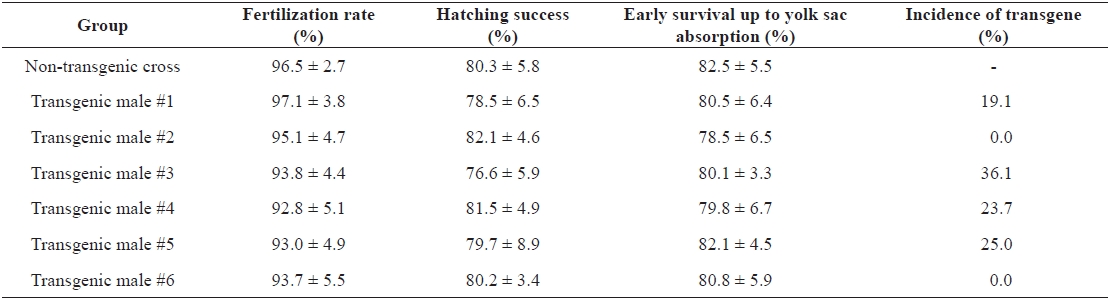

Although the present study was limited to a few transgenic founder males, no notable alteration of their reproductive ca-pacity was found in terms of milt production (data not shown). However, significant depression or retarded gonad develop-ment has been reported previously in fast-growing transgenic carp harboring an ‘all-cyprinid’ GH construct (Fu et al., 2005). Thus, further evaluations of reproductive performance of large numbers of autotransgenic carp should be conducted for both sexes. Artificial insemination between milt from transgenic males and eggs from normal females resulted in fairly good scores for both fertilization rate and hatching success, which were not different from those in control crosses using normal gametes (Table 1). Transgene inheritance to the subsequent generation was detected in four of six crosses as judged by PCR typing of F1 larvae. However, as expected, all of the founder transgenic males were determined to be mosaics, as evidenced by a germ-line transmission frequency lower than 50% (Table 1). All four F1 progeny groups showed a stimulated pattern of body weight increase during the early stages. Although strain-specific differences were observed during early growth, many transgenic individuals belonging to the F1 groups could be distinguished from their non-transgenic siblings by the naked eye at 2 weeks of age. From the growth trial up to 2 months of age, weight gains in the transgenic groups ranged from 3.6- to 6.3-fold those of the non-transgenic groups, suggesting that the growth response to the present GH-transgenesis is repro-ducible in subsequent generations (Fig. 2). The results of this study advocate the use of the autotransgenic strategy for GH-transgenesis of other farmed fish species. Further studies are needed to examine the stable inheritance of geno- and phe-notypes through subsequent generations. In addition, several breeding strategies, including chromosome-set manipulations followed by field tests, are needed to select the most desired strain of the autotransgenic carp (Nam et al., 2004; Kapuscin-ski, 2005).