The brown seaweed Ecklonia cava Kjellman is abundant in the subtidal region of Jeju Island and the southern coast of Ko-rea. It is used as abalone feed (Kang, 1968) and in treatments of hemorrhoids and gastroenteritis, as well as insecticide, as recorded in the Oriental medical textbook Donguibogam pub-lished in 1613 (Donguibogam Committee, 1999). E. cava is also used as a source for an immune-booster, which has been claimed to contain antitumor, anticoagulant, and antithrombin polysaccharides (Koyanagi et al., 2003). The seaweed con-tains marine polyphenols known as phlorotannins (Li et al., 2009), which are found only in brown algae, synthesized via an acetate-melonate pathway and formed by the polymeriza-tion of phloroglucinol (1,3,5-trihydroxybenzene) (Ragan and Glombitza, 1986). Recently, accumulating evidence suggests that E. cava exhibits matrix metalloproteinase inhibitory ac-tivity (Kim et al., 2006), bactericidal activity (Jin et al., 1997), protease inhibition (Ahn et al., 2004), and effects on osteo-arthritis (Shin et al., 2006), asthma (Kim et al., 2008), and melanogenesis (Heo et al., 2009). Numerous studies have examined the antioxidant properties of extracts (Jung et al., 2009) or chemical components (Kang et al., 2004; Heo et al., 2009; Li et al., 2009). E. cava polysaccharide also showed anti-inflammatory activity mediated by inhibition of NO and prostaglandin E2 production (Jung et al., 2009; Kang et al., 2011). The underlying mechanism may involve repression of inflammation by antioxidant substances (Garrett and Grisham, 2005). Thus, to evaluate the anti-inflammatory activities of E. cava, we assayed in vivo the anti-inflammatory activities of dichloromethane, ethanol, and boiling water extracts against hyperpyrexia, algesthesia, edema, erythema, and local blood flow in mice.

Thalli of the brown seaweed E. cava were collected from the coast of Kijang, Korea, from August 2008 to 2010. The scientific name of the seaweed described in the Donguibogam was identified from its common or local names (Suh, 1997). A voucher specimen is deposited in our laboratory (Y. K. Hong). For convenience, the seaweed tissue was completely dried for 1 week at room temperature and then ground to powder for 5 min by a coffee grinder. The powder was stored at -20℃ until use. Dichloromethane or ethanol (1 L) was used to extract 20 g of the seaweed powder by shaking at room temperature for 1 h. For the water-soluble fraction, distilled water was boiled for 1 h. The crude extract was evaporated under vacuum and dried under nitrogen. To remove salt from extracts, extractions were repeated several times (from the previous solvent-solu-ble fraction) until the amount of salt was visibly negligible.

BALB/c mice (8-10 weeks old; 20-25 g body weight) were used to assay various anti-inflammatory activities. The animals were kept at room temperature (24 ± 1℃) on a 12 h light/dark cycle with free access to food and water. Animal experiments were performed in accordance with the U. S. NIH Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

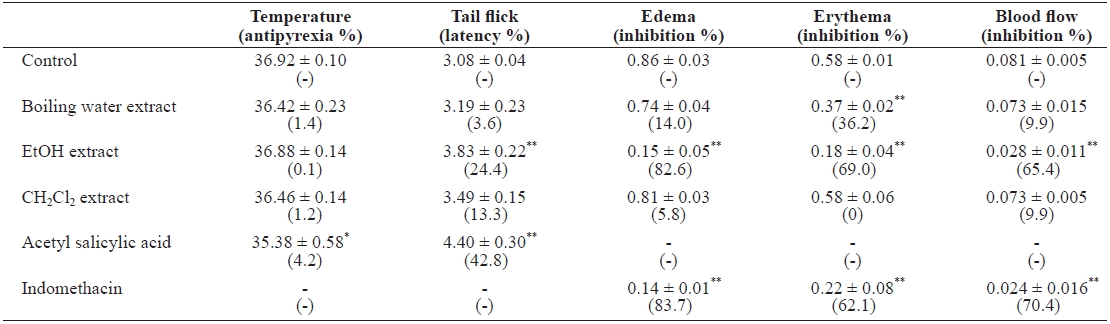

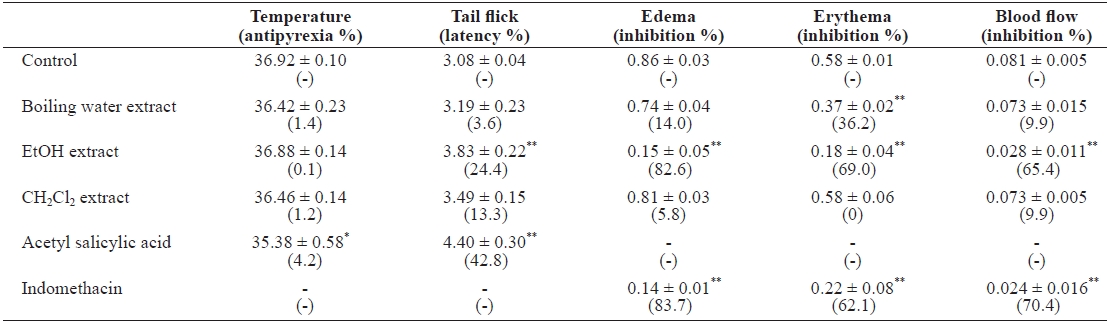

A brewer’s yeast-induced pyrexia mouse model was used to determine the antipyretic activity (Teotino et al., 1963). When the rectal temperature peaked after 24 h, extracts (4 g) in 10 mL of 5% Tween-80 or 10 mL of 5% Tween-80 (control) per kg body weight were administered orally, and the rectal tem-perature (℃) was recorded after an additional 45 min using an electric thermometer connected to a probe, inserted 2 cm into the rectum. Relative temperature suppression (%) is expressed as [(value of the control - value of the extract)/value of the control] × 100. Acetyl salicylic acid (aspirin, 150 mg/kg, p.o.) was used as a standard.

In the tail-flick test (Gray et al., 1970), extracts (1.5 g/10 mL of 5% Tween-80/kg body weight) or control was adminis-tered i.p. to mice, and tail-flick latency time(s) was measured 1 h later using a tail-flick unit (Ugo Basile, Varese, Italy). Rela-tive latency (%) was expressed as [(value of the extract - value of the control)/value of the control] × 100. Acetyl salicylic acid (150 mg/kg, p.o.) in the same volume of vehicle was used as a standard.

Stock solutions of the extracts were prepared by adding etha-nol (1 mL) to dried seaweed extracts (40 mg). Phorbol 12-my-ristate 13-acetate (PMA; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) in ac-etone (0.2 μg 10 μL-1 ear-1 ) was combined with the seaweed extracts in ethanol (0.4 mg 10 μL-1 ear-1 ) and topically applied to the whole inner side of the mouse’s ear. Ear edema was mea-sured after 10 h using a spring-loaded micrometer (Mitutoyo Corp., Tokyo, Japan) (Griswold et al., 1998). Ear erythema was determined at 10 h by digital photography, adjusted to balance white, and Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe, San Jose, CA, USA) was used to measure the magenta value (Khan et al., 2008). To confirm the anti-inflammatory activity of the seaweed, local blood flow in the mouse ear was measured by laser speckle flowgraphy (In-flameter LFG-1; SoftCare, Fukuoka, Japan) (Lee et al., 2003). Edema (AU), erythema (AU), and blood flow (AU) values were calculated as (I10 - I0)/I0, where I10 is the measurement 10 h after PMA application and I0 is the measurement at 0 h. The relative inhibition rate (%) was expressed as [(value of the control - val-ue of the extract)/value of the control] × 100. Indomethacin (0.3 mg 10 μL-ethanol-1 ear-1 ) was used as a standard.

Mice were fasted for 6 h, with water provided ad libitum. Extracts (5 g/10 mL of 5% Tween-80/kg bw) were admin-istered orally to mice (n = 5, each). The animals were then observed for any abnormal behavior for 3 h, and mortality was noted for up to 2 weeks. A group of animals treated with Tween-80 served as the control.

All animal experiments were performed with at least seven mice per group, and the highest and lowest values were dis-carded. Data are presented as means ± SE. The significance of the results was calculated using Student’s t-test, and differ-ences were deemed statistically significant at P < 0.01.

When preparing traditional medicines and health care foods, the materials are commonly boiled in water or soaked in beverage alcohol. To undertake more detailed investiga-tions of the active substances in E. cava, we prepared boiling water-, alcohol-, and dichloromethane-soluble seaweed ex-tracts. Brownish extracts of boiling water (yield, 15.6%), eth-anol (yield, 1.7%), and dichloromethane (yield, 0.3%) were obtained. The antipyretic activity was evaluated by measuring changes in rectal temperature. When the mice were injected with brewer’s yeast, the rectal temperature peaked at 39.19 ± 0.07℃, which was above the normal 38.45 ± 0.06℃, at 24 h. Oral administration of the extracts marginally lowered rectal temperatures in hyperthermic mice (Table 1). Tail-flick behav-ior was used to evaluate extract analgesic activity. As controls, mice injected with 5% Tween 80 responded by tail flicking in 3.08 ± 0.04 s. I.p. injection of ethanol extract increased the la-tency by 3.83 ± 0.22 s. The conditions for inducing mouse ear edema, erythema, and local blood flow by topical application of PMA were optimized by applying 0.2 μg PMA and mea-suring ear thickness after 10 h. PMA mixed with the ethanol extract (0.4 mg/ear) demonstrated an edema value of 0.15 ± 0.05 AU, representing 82.6% inhibition compared to the PMA control (Table 1). Indomethacin (0.3 mg/ear), a standard anti-inflammatory drug, showed 0.14 ± 0.01 AU, with 83.7% inhi-bition when applied with PMA to the mouse ear. The observed erythema value with 0.2 μg PMA was 0.58 ± 0.01 AU. PMA plus ethanol extract (0.4 mg/ear) demonstrated an erythema value of 0.18 ± 0.04 AU, with 69.0% inhibition. Indomethacin showed 0.22 ± 0.08 AU, with 62.1% inhibition. To confirm the inhibition of edema and erythema, we measured local blood flow by laser speckle flowgraphy. The blood flow value for 0.2 μg PMA was 0.081 ± 0.005 AU, and that of the PMA plus ethanol extract was 0.028 ± 0.005 AU. E. cava ethanol ex-tract (i.e., likely nonpolar compounds) showed potent in vivo anti-inflammatory activities (P < 0.001) in mice. We evalu-ated acute toxicity of the extracts, even though the seaweed is used as feed and herbal medicine in Korea. During the 2-week observation period, no death occurred in any group (n = 5) ad-ministered 5 g/kg bw. Most of the mice administered extracts reacted immediately by jumping, sleeping, scaling, and writh-ing for 5-10 min, and returned to normal behavior after 1.5 h.

In this study, we demonstrated that E. cava ethanol extract inhibited PMA-induced inflammation. Topical application of PMA induces a long-lasting inflammatory response, result-ing from protein kinase C (PKC) activation associated with a transient increase in prostanoid production and marked cel-lular influx (Nishizuka, 1989). This high prostaglandin level is likely due to cyclooxygenase (COX) induction (Muller-Deck-

er et al., 1995). Treatment of mouse skin with a PKC activa-tor, such as PMA, induces the formation of free radicals in vivo (Wei and Frenkel, 1992). E. cava has intracellular radical scavenging activity in BV2 microglia, suggesting a possible mechanism for the inhibitory effect of E. cava on NF-jB ac-tivation (Jung et al., 2009). Therefore, the potential inhibition of reactive oxygen species generation by E. cava is consistent with the inhibition of NF-jB-dependent cytokines and induc-ible nitric oxide synthase and COX-2 expression, and thus reduced inflammation. The tail-flick response is believed to be a spinally mediated reflex (Chapman et al., 1985). Several inflammatory mediators produce algesthesia by peripheral and spinal sensory fiber sensitization through protein kinase activation, including PKC (Scholz and Woolf, 2002). Alges-thesia is associated with the formation of edema and erythema by PMA treatment (Tsuchiya et al., 2005), and thus the main active constituents in E. cava ethanol extract may inhibit the pathway that mediates the pain, edema, and erythema associ-ated with inflammation. An herbal medicine is considered tox-ic if the LD50 is lower than 5 g/kg body weight (World Health Organization, 1992). Thus, the E. cava extracts are not toxic and can be safely used by humans at moderate doses, since no mortality at 5 g/kg bw was recorded. In conclusion, our data indicate that ethanol extract of the brown seaweed E. cava has anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities in vivo, with no se-rious toxic effect at moderate doses. These findings reinforce the claims of the health care industry and indigenous medicine that E. cava can be used as a remedy for inflammation-related symptoms.