Like their German counterparts, Japanese universities pose one puzzle: no international recognition in world rankings of universities despite their high levels of postwar economic and technological developments. Notwithstanding nine Nobel prizes Japanese professors have garnered in the area of natural science since the end of the war, the world rankings of Japanese universities, especially those of Tokyo and Kyoto National Universities, have never reached beyond the 24th place. One of the results of this mixed blessing is the low R&D investment by Japanese multinational enterprises (MNEs) in their local universities. Not only Japanese MNEs, but foreign firms also shied away from collaborating with top notch Japanese universities for technology commercialization. Instead, such giant Japanese firms as Toyota, NEC, and Sony built their own internal R&D centers and/or worked closely with foreign R&D centers for developing and commercializing cutting-edge technologies. The majority of university-firm research collaborations in Japan have been based on personal ties that did not necessarily result in technology commercialization (Kato and Enomoto, 2006; Ito, 2008).

To resolve this problem, the Japanese government has continuously implemented aggressive policies to encourage and consolidate university-firm R&D alliances (e.g., “Seeds Innovation”) since the onset of the economic recession in 1989 (MEXT, 2008). This new policy drive was also part of the bigger project of reforming Japanese universities, which intended to boost global competitiveness of Japanese universities and to attract more fee-paying foreign students and world-class scholars. However, the whole reform package was based on the traditional Japanese technology management practices of emphasizing radical or leading technological innovation projects that would “produce innovation from [traditionally strong] fundamental scientific research that can be sustainable through not only domestically but internationally viable strategies” (MEXT, 2008). Radical innovation projects utilize what many call feed-forward learning, an innovation process that requires the exploration of new knowledge, instead of the exploitation of existing knowledge. New firm-university projects of developing medical robots for Japan’s ageing society are some of the ambitious examples that emphasize feed-forward learning in innovation. Japan’s robotics market is the largest in the world, which is valued at $7 billion, and the government intends to expand and dominate the market globally through industrial and consumer (e.g., medical, sanitation, and entertainment) robots (JETRO, 2011).

However, this paper finds that most of these programs of fostering university-firm alliances toward feed-forward learning have not been as successful in fostering R&D investments from the MNEs on the one hand and boosting the global competiveness of Japanese universities as the claim made for them by the program administers. It is therefore argued in this paper that Japanese universities and firms should shift their focus to feedback from feed-forward learning as a way to reform the lackluster performance of firm-university R&D collaboration. This paper first discusses theoretical backgrounds of feed-forward and feedback learning in university-firm alliance toward radical and incremental innovation. After establishing core theoretical distinction between feed-forward and feedback learning in innovation and identifying problems associated with these two types of learning, I analyze the case of Waseda University for its leading role in creating university-based venture startups in Japan in a way to leverage Japanese firm-university research alliances. The paper also provides a short discussion of a possible expansion of feedback to feed-forward learning.

2. Feed-forward and Feedback Learning

In the study of university-firm alliances for organizational learning and new knowledge development, researchers have mainly focused on the issues of facilitating factors of university-firm alliances (Geisler, 1995; Cassiman and Veugelers, 2002; Santoro and Chakrabarti, 2002; Tether, 2002; Fontana et al., 2006); finding structural or firm-level contingencies for preferring university over private firm partners for R&D alliances (Teece, 1985; Kogut, 1988; Rosenberg and Nelson, 1994; Berkovitz and Feldman, 2005); the role of the government in galvanizing alliance formations (Capron and Cincera, 2003; Mohnen and Hoareau, 2003; Eom and Lee, 2010); and developing the legal and governance framework of such alliances (Cassiman and Veugelers, 2002). However, to many universities in Japan, Germany, France, Italy, Spain, and Scandinavia, a lingering question is: how to attract major multinational enterprises (MNEs) for their university-firm alliance projects. The harsh reality is that most of these MNEs elect to work with their internal or international R&D hubs and/or prestigious U.K. or U.S. universities for feed-forward knowledge development (Love and Roper, 1999; Santoro, 2000; Monjon and Waelbroeck, 2003; Freel and Harrison, 2006).

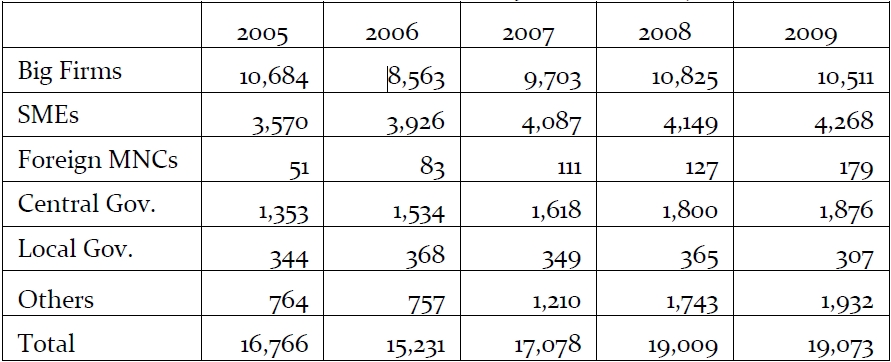

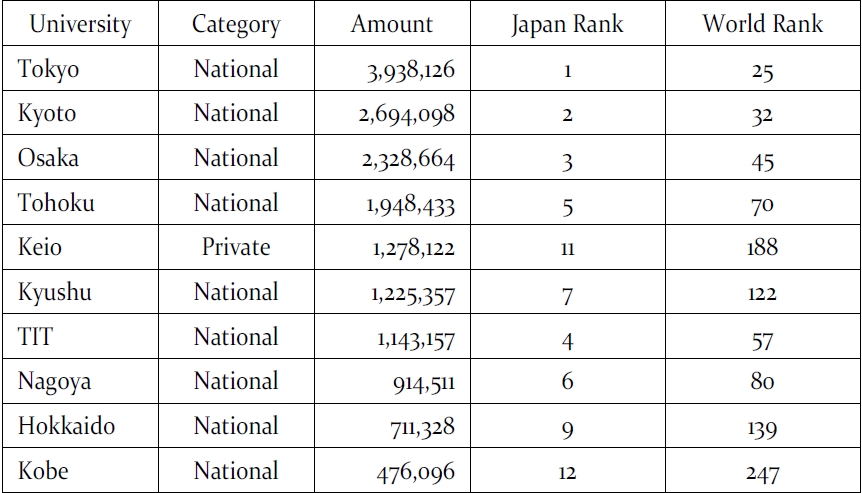

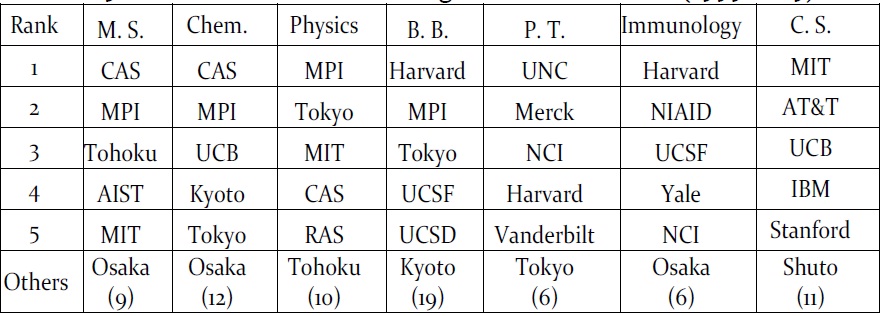

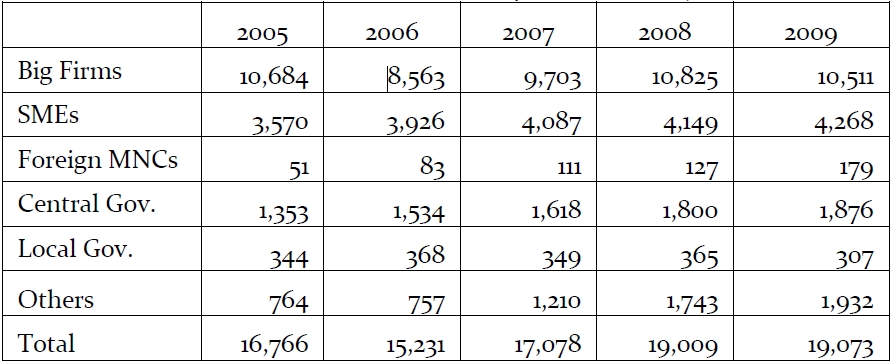

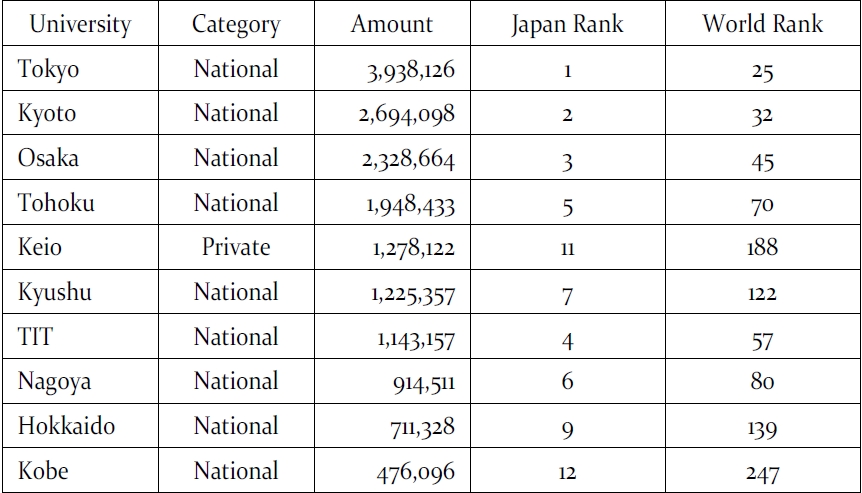

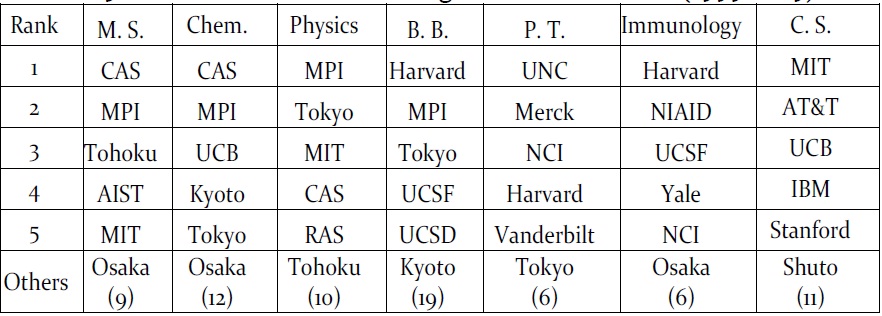

In Japan high ranking universities like Tokyo National University, Kyoto National University, Keio University, Waseda University, Tokyo Institute of Technology, and Osaka University are having tough time attracting not only fee paying foreign students or internationally renowned faculty, but collaborative research projects funded by globally leading MNEs like JP Morgan, GE, Exxon Mobil, HSBC, BP, AT&T, Wal-Mart, P&G, IBM, and other Forbes top 100 firms. As Tables 1 and 2 show, the bulk of the research funding awarded to universities between 2005 and 2009 were from big Japanese firms, while the number of collaborative projects with foreign MNCs was negligible (less than 1% of total projects). Furthermore, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and private universities have continuously and systemically been excluded from the Japanese style firm-university R&D partnerships. Among the top ten recipients of R&D funds from Japanese firms, only one university was a private: Keio University. Although Waseda University’s world ranking was higher than that of Keio in 2011, Waseda couldn’t secure a top ten spot on the national funding list. The nine national universities that received the most of the firm-university R&D funding, however, fared miserably in the world rankings, especially Kyushu, Hokkaido, and Kobe.

[Table 1] Number of Firm-University Joint R&D Projects

Number of Firm-University Joint R&D Projects

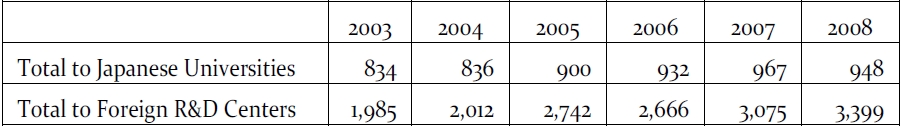

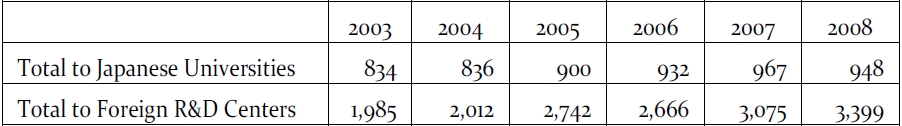

What’s worse, just like foreign MNEs, Japanese MNEs have also shied away from the firm-university R&D projects. As Table 3 shows, Japanese firms have allocated R&D funding to foreign R&D centers two to four times what they have spent for domestic universities. This is a clear indication that Japanese firms would work closely with foreign R&D centers for breakthrough knowledge (i.e., feed-forward learning), whereas they would not be as much interested in working with Japanese universities for similar innovative projects.

[Table 2] Total Firm-University R&D (2009) and University Rankings (2010)

Total Firm-University R&D (2009) and University Rankings (2010)

[Table 3] R&D Spending by Japanese Firms

R&D Spending by Japanese Firms

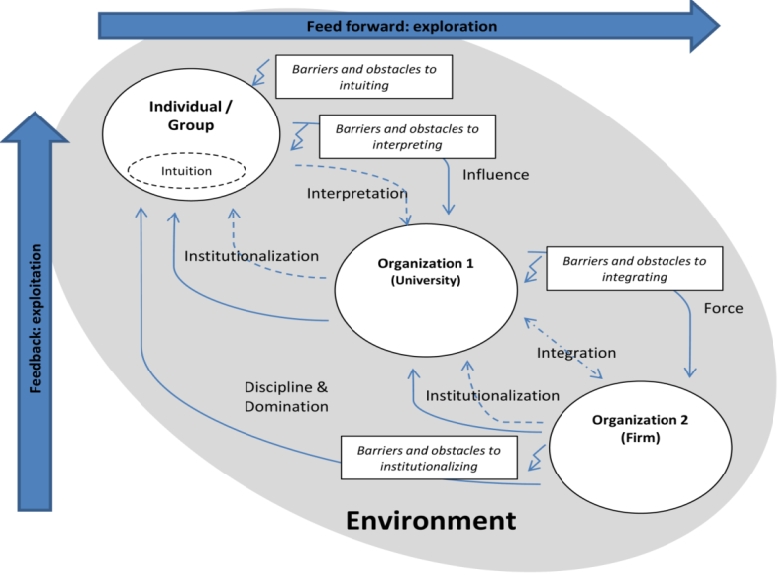

To analyze the declining nature of the university-firm alliance in Japan, I employ the concept of “barriers” to (inter-)organizational learning (Coopey, 1995; Berthoin-Antal et al., 2003; Lawrence et al. 2005; Schilling and Kluge, 2009). The barriers to the firm-university alliance toward interorganizational learning in Japan usually occur at the level of “integration,” if I use Crossan et al.’s (1999) famous 4I model (intuition-interpretation-integration-institutionalization). This integration of firm-university R&D cannot be consolidated because leading Japanese MNEs and SMEs refuse to accept the “interpretation” proposed by the Japanese universities. The 4I model is useful in that it uses four cyclic stages of feed-forward and feedback learning.

Barriers to integration in interorganizational learning include political obstacles (Coopey, 1995; Lawrence et al. 2005) and cognitive biases and mind-sets held among actors, groups, and organizations (Berthoin-Antal et al., 2003). However, others have also noted structural and environmental factors (March, 1991; Van de Ven and Polley, 1992; Kim, 1993; Nonaka, 1994; Zander and Kogut, 1995; Edmondson and Moingeon, 1996; Inkpen and Crossan, 1996; Schilling and Kluge, 2009). Barriers therefore occur at the levels of individuals, groups, organizations, and environments. Political obstacles and cognitive biases and mind-sets mainly include self or group interests that are incongruous with structural or organizational interests. Informal politics within organizations often affirms the existence of informal charismatic leadership that espouses to perpetuate employees’ gold bricking. Under informal leadership, employees can be motivated to defect from learning or pursue other activities that are irrelevant to organizational learning toward innovation (Coopey, 1995; Zell, 2001; Szulanski, 2003, Beer et al., 2005; Lawrence et al. 2005).

Fear of disadvantages, punishment from organizational learning and/or failures (Argyris, 1990; Cannon and Edmondson, 2001; McCracken, 2005; Sun and Scott, 2005), lack of authority within the university (Popper and Lipshitz, 2000; Starbuck and Hedberg, 2003), lack of top management support (Elliott et al., 2000; Lawrence et al., 2005), and defensive routines of MNEs (“not invented here syndrome”) (Zell, 2001) are other individual-group level barriers of interorganizational learning.

As Table 3 shows, it is obvious that Japanese MNEs do not spend R&D money in collaboration with Japanese universities as much as they do with universities and R&D centers in North America and the E.U. In addition, corporate decision makers do not want to risk their resources by commissioning new explorative projects to Japanese universities, unless these projects are politically beneficial to the firm or pertain to necessary fundamental technologies that are conducive to feed-forward learning for future commercial projects. Even when Japanese universities present to Japanese MNEs new explorative knowledge with high levels of tacitness, the latter’s defensive routine or the “not invented here’ syndrome persists. This is because the fear of failure on the part of both MNE decision makers and university researchers is abnormally high in Japan vis-a-vis their counterparts in North America or Western Europe (Morioka, 2007).

Among the structural-organizational factors, low turnover rates and high level of workforce homogeneity, especially among top management teams (March, 1991; Virany et al., 1992); competition with other MNEs that are tied with universities in North America and Western Europe (Sun and Scott, 2005); competence traps within the MNEs through long term success in their cooperation with universities other than Japanese ones (Levitt and March, 1998; Berthoin-Antal et al., 2003); inadequate communication between MNEs and universities (Elliott et al., 2000; Zell, 2001); political and power structures (Coopey, 1995; Beer et al., 2005); ineffective resource allocation (Beer et al., 2005); lack of learning values (Sun and Scott, 2005); and lack of cultural fit between innovation needs and organizational culture (Sun and Scott, 2005) are considerably powerful variables in explaining the barrier to interorganizational learning.

In the Japanese case, professors are too homogenous with low turnover rates, whereas Japanese MNEs face stiff competition in the global market, where their competitors constantly work with leading research universities in North America and Western Europe. The long term success that Japanese MNEs have enjoyed in their alliance with other universities than the Japanese also reaffirmed their corporate norm not to associate with Japanese research centers. Political and power structures within the nation also discouraged interorganizational learning between Japanese MNEs and universities, mainly because a strong line of distinction has existed between universities and industries. University professors always consider themselves as part of an ivory tower with influential positions in Japanese power and politics (Ito, 2008). However, lack of communication, ineffective resource allocation, and lack of learning values do not seem to apply to the Japanese case.

Among the societal-environmental factors, industrial structures not welcoming innovation (Spender, 1989) and failure traps (i.e., time lag between organizational actions and environmental responses) (Berthoin-Antal et al., 2003; Hedberg and Wolff, 2003) stand out as critical hindrances to integration. In the case of Japan, universities usually maintain an industrial structure that encourages fundamental studies with long term perspectives. This is in large part due to their success in getting Nobel prizes in physics, chemistry, and physiology or medicine (Ito, 2008). However, the basic nature of the fundamental research is still focused on the “catching up” of the fundamental research in the U.S. and the U.K. (Morioka, 2007). Government funding also targets at long term fundamental projects, inadvertently forgetting the fact that Japanese universities continue to charge higher R&D and licensing fees to Japanese companies during and after R&D collaboration, using template contracts [

In sum, the Japanese failure of integration in the interorganizational learning model derives from all three levels of causes: individual/groups, structure/organizations, and societal/environment. This fact requires a solution at each stage of the four-steps of interorganizational learning (IOL) progression (i.e., intuition, interpretation, integration, and institutionalization).

3. Overcoming Barriers to Intuition and Interpretation through Feed-Forward Learning

Japan is the only G7 member from Asia with the third largest GDP in the world. Notably, the country is known for its ability to narrow the technology gap between Western leaders and Japan and to make products and technologies better than their predecessors. This process is often referred to as

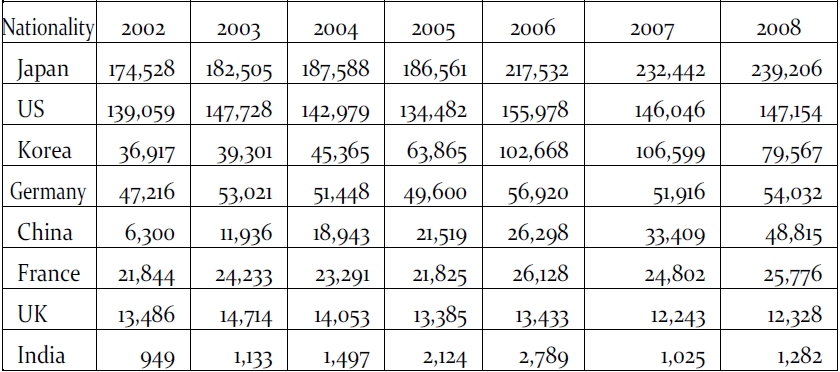

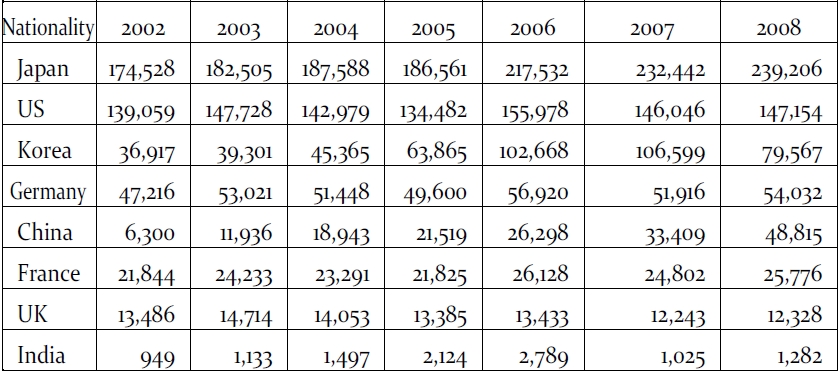

[Table 4] Number of New Patent Registrations (WIPO)

Number of New Patent Registrations (WIPO)

Crossan et al. (1999) defined intuition as an individual or group level experience of new ideas and insights for a possible future innovation. In a similar vein, interpretation is the next step of articulating these new ideas and insights to other individuals and groups within an organization. Finally, integration is the third process of integrating individual and group interests together for innovation within an organization. The 4I model can be expanded to IOL, as individual and groups at a university can experience new ideas and insights and decide to articulate them to an MNE for a potential collaboration toward commercialization. If both parties agree, universities and MNEs can integrate their group interests together to produce innovation for the two organizations (Figure 1).

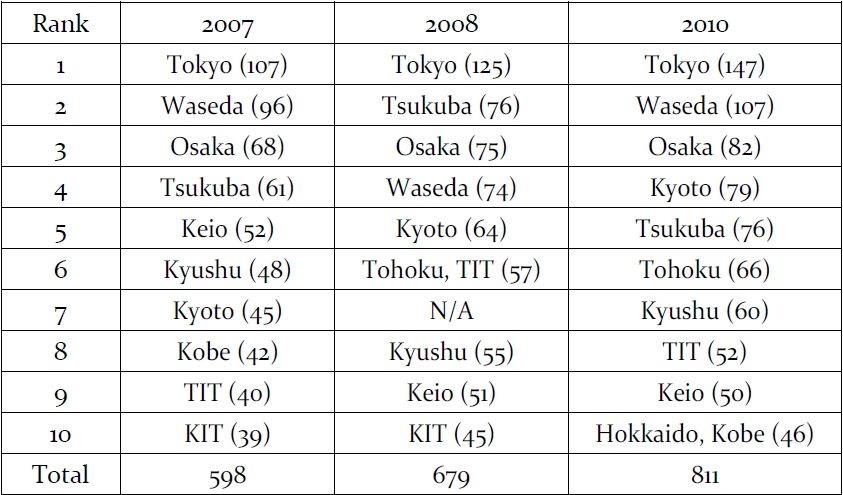

[Table 5] International Citation Rankings in Natural Sciences (1999-2009)

International Citation Rankings in Natural Sciences (1999-2009)

Leading Japanese MNEs like SONY and Toyota, on the other hand, have completed all four stages of intuition, interpretation, integration, and institutionalization either within their own organizations (OL) or with other organizations (IOL) and successfully created the cutting edge technologies in their own markets. However, since Japanese national universities refuse to be part of the 4I process for the Japanese MNEs as feedback learners for the stage of institutionalization, Japanese MNEs could not institutionalize IOL with Japanese partner universities, reducing the total R&D support provided to the universities vis-a-vis foreign R&D centers (Table 3).

In a nutshell, the Japanese path to development and world leadership in science and technology research during the postwar years has been typified by the ivory tower image of the national universities that boasted their splendid track record of success in fundamental research along with Nobel prizes in three science fields. Concurrently, Japanese MNEs boasted their international success in new patent registration, commercialization of fundamental research with foreign R&D centers, and

Shockingly however, Japanese global competitiveness fell to the 9th place in 2011 from the 1st in the 1980s, mainly because of Japan’s devastating 28th and 11th ranks in the world, respectively, in the category of “basic requirements” and “efficiency enhancers” (WEF, 2011). The reason Japanese basic requirements are worse than those of Taiwan (15th) or Korea (22nd) lies in the macroeconomic management failure. The snowballing government’s debt servicing, along with its inability to ease the quantitative shortage of the Yen stock, fundamentally harms the ability of the private sector to make an effective investment and other financial decisions, despite the fact that Japan still maintains the 3rd place in innovation and sophistication factors. In addition, the reason Japan’s ranking was only the 11th in “efficiency enhancers” mainly derives from the weakness in higher education and training, financial market development, and technological readiness.

The declining efficacy of Japan’s higher education and training has been continuously discernible since the 1990s. Japanese universities began experiencing rapidly declining student enrolments due to the sinking birth rate. Many students elected to attend universities in North America, Australasia, and Western Europe, as the strong Yen made it possible for them to afford education in the West. Many regional and private universities had no other option but to recruit Chinese and Korean students

The government’s response to the overall devastation of the Japanese universities and their incompetence in creating new economic values amid economic recession in the 1990s was to abandon the catching up model of economic development. Instead, it emphasized the leadership knowledge management model that involves an endless feed-forward and feedback flow among educational institutions, firms, and the market, where new technologies are disseminated. To ensure this, the government strengthened intellectual property (IP) protection by strictly enforcing IP law and expanding the range of IP protection. The liberalization and deregulation of the knowledge market entailed the privatization of education, which technically enabled universities and graduate schools to freely open and/or close degree programs based on market demands, actively recruit renowned foreign faculty members, and strictly implement course and teaching evaluations (Daigaku Shingikai, 1998).

This new reform blue print for the Japanese higher learning was put into action in part by the Science and Technology Basic Plan (2001-2006). The Japanese government pledged to provide $240 billion to science and technology research projects over the course of five years, the second largest sum in the world after the U.S. expenditure (Taguchi, 2003:156). The program is now in its second phase, encouraging incessantly the linkage between universities and firms [

However, the Japanese Triple Helix is fraught with structural and institutional problems and/or immaturity. First and foremost, firms and universities maintain no clear agreement as to how they will utilize research results. As mentioned earlier, firms usually do not have a clear idea of commercialization when universities produce research results based on some fundamental research. Making things worse, universities often require a contractual clause that requires settlement fees for the failure of technology/knowledge utilization [

The Science and Technology Basic Plan (STBP) further worsened firm-university R&D relationships, particularly over the issue of sharing research results and overheads. As the 2004 amendments to the Patent Law indicate, Japanese universities showed an enormous level of uneasiness about sharing research overheads and patent-related fees. Firms, however, detested the idea of information sharing between universities and corporate R&D centers, because they did not want to see their corporate secrets being disclosed to the participating universities and potentially to competitors. Universities hesitated paying for the patent application fees, expecting additional subsidies from the firm or the government under the rubric of STBP. The 2004 amendments therefore reduced patenting fees, as long as university TLOs send in patent applications just to ease this tension between universities and private firms (Miyata and Nishimura, 2007).

In sum, the top-down pressure for publications in international journals and monetary incentives for university-industry alliances easily motivated universities and professors to seek R&D partners with MNEs, if not with SMEs. However, since the ties with MNEs were fraught with difficulties and usually one shot in length, wholly relying on the governmental and corporate funding, the successful institutionalization of IOL still looks unlikely in the near future. Hesitant Japanese MNEs that would rather rush to foreign R&D centers than beg the Japanese national universities for a better R&D contract also signals that the full integration of innovative ideas, originating from Japanese universities, has not yet taken place within the Japanese MNEs. Therefore, if both universities and MNEs rely on feed-forward learning only, it is deemed impossible for them to realize the final two stages of integration and institutionalization in IOL. Japanese MNEs want Japanese national universities as feedback learners, whereas university professors want to be feed-forward learners. How can Japanese policymakers motivate some of their professors to be feedback learners?

4. Motivating Feedback Learning for Integration and Institutionalization

Feedback learning involves the exploitation of knowledge until a learner can master or improve it. Exploitive learners would also try to expand, if possible, the practical and commercial applicability of new knowledge to unexplored areas through procedural memory.

Motivating feed-forward learning (i.e., intuition and interpretation) is relatively easier for organizations to handle than feedback learning (i.e., integration and institutionalization), although it is equally difficult for organizations to ensure desired performance results from both types of learning. If we summarize the previous literature review, feed-forward learning is much more individually or collectively challenging and therefore fascinating than feedback learning. As long as organizations don’t punish OL failures, and political culture encourages radical innovation as in Silicon Valley, individual and group learners can freely enjoy the thrills they experience in exploring new knowledge. However, internalizing extant knowledge for standard operation procedures is dull, repetitive, and monotonous. This is why feed-forward learning is individually motivated (i.e., empowering individuals to change organizations), whereas feedback learning is organizationally motivated (i.e., depowering individuals to accept new organizational norms and procedures). Also, a huge difference in the resulting monetary rewards exists between each type of learning. A typical Toyota worker who is a leader of

How can we then motivate Japanese universities toward feedback learning in their R&D alliance with Japanese MNEs? According to recent findings in psychology, melancholia is a stronger motivator of feedback learning than simple nostalgia (Berlant, 1988; Greenfeld, 1990; Streip, 1994; Eng, 2000; ?i?ek, 2000; Diaz, 2006). Nostalgia occurs simply with ageing, a natural human psychological tendency to idealize things of passe. Melancholia on the other hand can occur in all ages, whether in their 20s or 60s. Melancholia is a psychological disorder diagnosed among the patients who are not allowed to express mourning even at the time of utmost sadness (Freud, [1917]1963; Kristeva, 1989). For example, even though one’s mother is executed by the government for treason, her daughter cannot openly express her sadness of losing her mother for fear of the political repression surrounding her.

What is interesting about melancholia is that many of the melancholic patients pursue learning while they suffer from the psychological disorder (Oh, 2011b). A famous example is Bill Murray, the depressed and possibly melancholic hero in the movie,

Experiencing

Some of the Japanese private universities can certainly motivate themselves toward feedback learning in order to transcend their

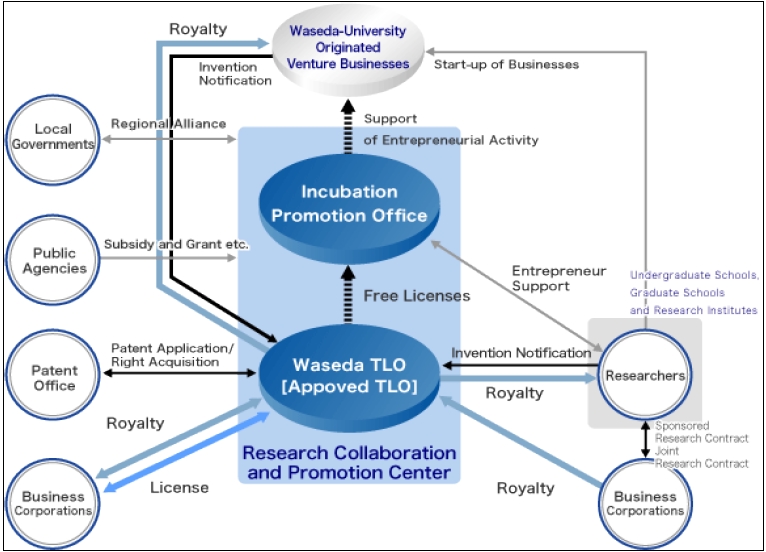

5. The Case of Waseda University Ventures

Some of the leading Japanese universities have started university based ventures [

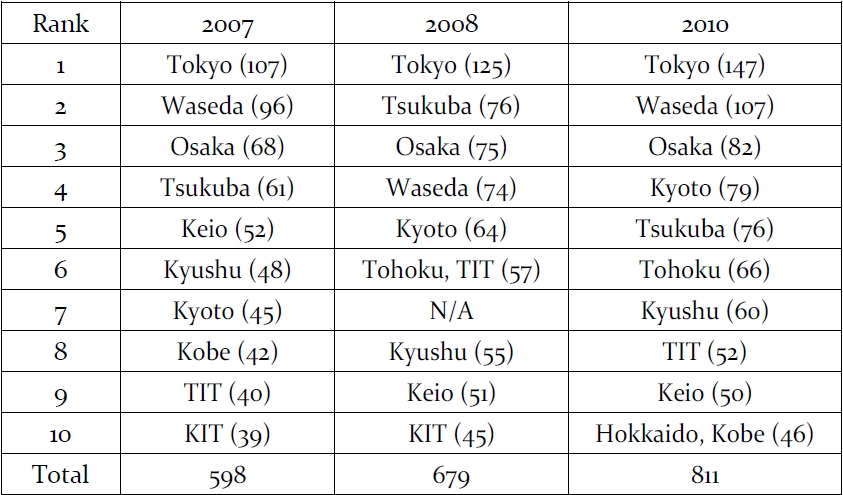

As Table 6 shows, Waseda is the only private university in Japan that is ranked 2nd in Japan in terms of the total number of university-based ventures it has created until 2010. Provided that national universities would receive most of the governmental funding and firm-level support, the second place in 2007 and 2010 that Waseda garnered is phenomenal (see also Table 2).

As Table 6 indicates, 63.4% of all top 10 university-based ventures were created by national universities in 2007, while the number for private universities was only 29.5% (Ogura, 2008:133). However, since the majority of these start-ups are concentrated in the areas of life sciences (35%) and IT software (30.2%) in 2008, we can argue that the majority of these national universities still emphasize feed-forward learning in developing new medical robots and their IT software (METI, 2010:140). However, only 10% of these university ventures carry out technology commercialization in the area of manufacturing, such as automobiles (Ogura, 2008:135). This is clearly a Japanese phenomenon, because the manufacturing sector has traditionally relied on their own R&D centers or C&D with U.S. and E.U. research centers and/or universities for technology commercialization.

[Table 6] Total Number of University Based Venture Startups

Total Number of University Based Venture Startups

The key to Waseda’s rise to the 2nd place in Japan derives from the fact that the university focused on feedback learning and non-patent based technology transfers through high-tech human resources vis-a-vis the commercialization of new patents in creating venture startups. Consequently, Waseda’s IT software ventures that utilize standard technologies are currently the single most important group of venture firms that the university has created over the years, as they account for 35% of total ventures, whereas bio-ventures of feed-forward learning account for only 14% in 2011. Furthermore, non-patent based technology transfers to private firms through human resources account for 69% of all venture types in 2011 (WTLO, 2011).

Along with Tsukuba University, Waseda’s TLO (WTLO) was created four months after Tokyo University established its own for the first time in Japan in December, 1998. Since the amount of funding from the Japanese MNEs to Waseda has not been colossal, the most important financial source for the IT software ventures at Waseda has been the royalty payments from the MNEs after inventions in the form of

Although there is no crucial evidence at the moment, we can propose a hypothesis for future tests that the motivation toward feedback learning at Waseda was related to melancholia or

The Waseda case is enlightening for the Japanese economy that is striving to revolutionize its national and private university education system through firm-university alliances toward explorative knowledge development. However, the emphasis put on the national university system, which insists on fundamental scientific research, along with rigid ivory tower style R&D contracts (

Instead of fostering firm-university alliances for an economy that excelled in some industries but lagged behind in the quality of higher education, this paper argued that Japanese universities should envisage an alternative path toward a new Japanese style Triple Helix that specializes in feedback learning. The Waseda case suggests that the alternate path to firm-university alliances would result in a remarkable success, when facilitating conditions and other catalysts are present. This shift in the strategy of IOL requires changes in individual, group, and interorganizational motivation structures toward feedback learning. I postulated that one of the reasons Waseda succeeded in motivating feedback learning among their faculty was melancholia, which was present within the university-wide cultural structure. Putting feedback learning into action requires manageable programs and learning curricula. Based on the Japanese university-based ventures in general and the Waseda case in particular, successful feedback learning involves IT software development and servicing, which is based on standardized technology.

If feedback learning has been successful even when there was no significant monetary reward for learners, can it be developed into feed-forward learning for breakthrough knowledge? The answer to the question can be in the affirmative when it is confined to the Japanese case. As I argued, Japan has a long successful track record of breakthrough innovations, including analog technologies, parts productions, and lean manufacturing systems. Japanese universities continue to be global leaders in some fields of fundamental science studies. Through several cycles of feedback IOL between universities and MNEs, Japanese firms can teach universities new technologies and processes of explorative knowledge development, which the firms learned from their joint R&D projects with the U.S. and the E.U. R&D centers. In other words, if Japanese universities and MNEs recover trust by feedback IOL, MNEs will be less reluctant in transferring feed-forward IOL processes to these universities that has competency in improving Western institutions.

Using the revised 4I model with the distinction of feed-forward and feedback learning, I analyzed that the reason Japanese MNEs do not want to participate in the firm-university alliance was because national universities in Japan unanimously pursued feed-forward learning. In order to change this tendency and to galvanized more MNE participation into triple helix projects, I showed that the success of Waseda University in creating and sustaining venture startups derived from its emphasis on feedback learning. I contended that melancholia or

Further empirical and theoretical studies of the same topic can be devised using general data sets. The limitation of this study is not to have established the link between