T Tauri stars are generally believed to be low-mass (0.1-2

The

In this paper, we model dust around six sample CTTS using the optical properties of various amorphous and crystalline dust grains at different temperatures. We use a radiative transfer model for multiple isothermal circum-stellar dust shells (Towers & Robinson 2009). Even though the model ignores the disk geometry, it is useful to inves-tigate the overall properties of the multiple dust com-ponents around the central star. We compare the model results with the observed SEDs of the stars, including the ground-based, infrared astronomical satellite (

In this paper, we choose six CTTS. For these stars, good quality observational data including the

The high resolution

The

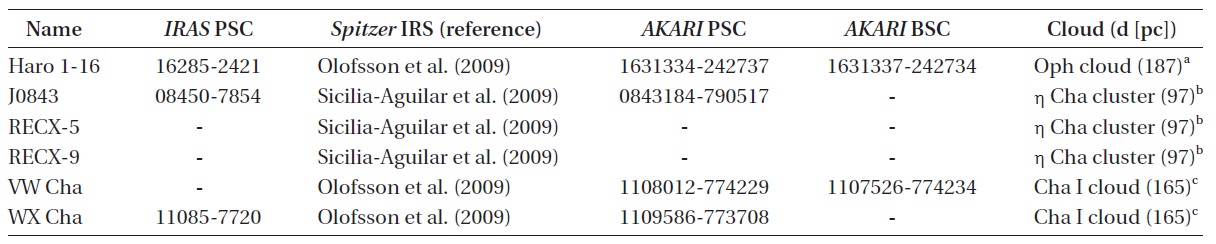

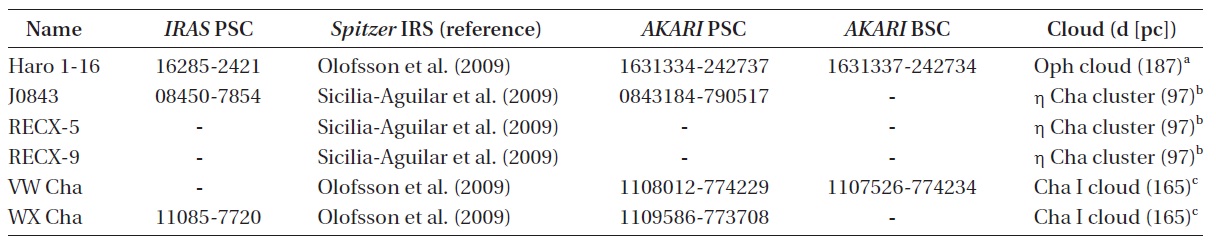

For each object, Table 1 lists the

To obtain the standard flux in W/m2 for all the data, we use the zero-magnitude calibrating method. The zero-magnitude calibrating data are taken from the related ref-erences. The observed SEDs of the six stars are displayed in Fig. 1. For

3. DUST ENVELOPE MODEL CALCULATIONS

The infrared SEDs of the CTTS show multiple broad peaks at 5-200 ㎛ (Sicilia-Aguilar et al. 2009). A reason-able explanation for this would be that there are multiple

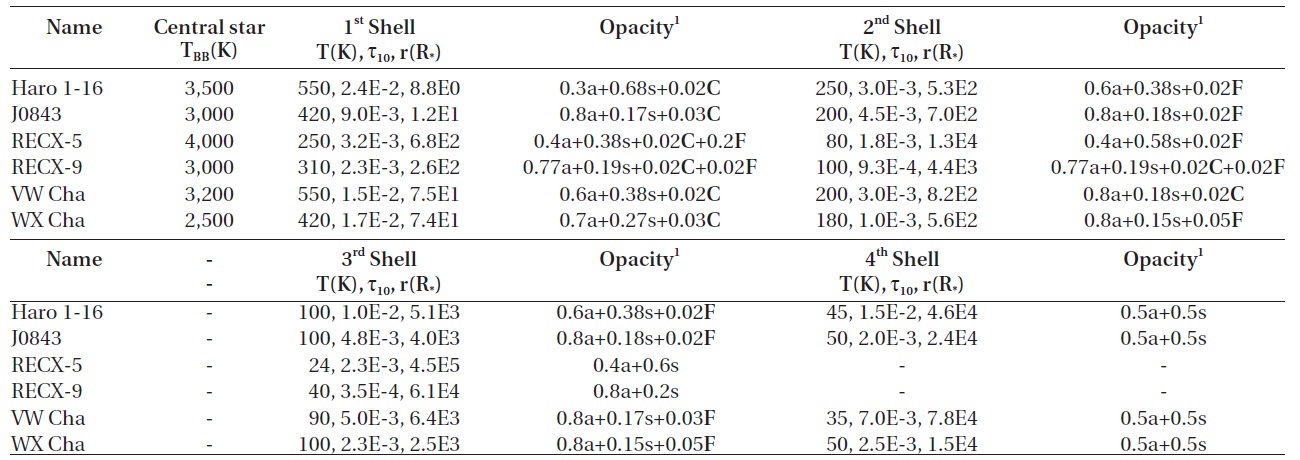

[Table 1.] Sample of classical T Tauri stars.

Sample of classical T Tauri stars.

dust components radiating multiple regions of infrared wavelengths. It is difficult to reproduce the observed SEDs with a single component dust model (e.g., DUSTY code developed by Ivezi? & Elitzur 1997). Many investiga-tors have tried to model the dust around T Tauri stars with a single component dust disk model (Miroshnichenko et al. 1999, Whitney et al. 2003), or using a simple Planck dust radiation law without considering absorption pro-cesses (Bouwman et al. 2008, Olofsson et al. 2010).

Suh (2011) modeled dust around Herbig Ae/Be stars using the radiative transfer model for multiple isothermal spherically symmetric circumstellar dust shells devel-oped by Towers & Robinson (2009), which assumes that each dust shell is in local thermodynamical equilibrium and that the temperature is constant. Dust grains in the innermost shell absorb the radiation from the central star and radiate at the equilibrium temperature. Dust grains in an outer shell absorb the radiation from the central star and the inner shell(s) and radiate at the equilibrium temperature. The scattering of light is ignored. These assumptions would be reasonable approximations for studying dust around T Tauri stars.

In this paper, we use the radiative transfer model for multiple isothermal circumstellar dust shells (Towers & Robinson 2009) to reproduce the observed multiple peaks and crystalline dust features. Though it is a rela-tively simple model, it can use the flexible parameters of dust properties to treat radiative processes through centrally heated multiple dust shells. The code would be useful to investigate the overall properties of complicated distribution of dust around a central star. We model dust envelopes around T Tauri stars using the optical proper-ties of various amorphous and crystalline dust grains at different temperatures.

Molecules in the atmospheres of CTTS make deep ab-sorption features in the near infrared region (Fig. 1). In this paper, we ignore absorption processes by molecules and concentrate on dust around the central star.

For the central star, we assume simple blackbody ra-diation. For each object, we use the best fitting effective temperature and list in Table 2. For all the sample stars, we assume that the luminosity is the same as the solar

luminosity (

The best fit model for the observed SED requires a proper combination of multiple isothermal components with different sets of diverse dust opacity functions. We have tried to use as many dust species as possible. We find that four dust species (amorphous silicate, amorphous carbon [AMC], crystalline corundum and crystalline for-sterite) are necessary to reproduce the SEDs of sample stars.

In this paper, we do not consider polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon for the radiative transfer model calculations, because its thermal properties are not yet well known.

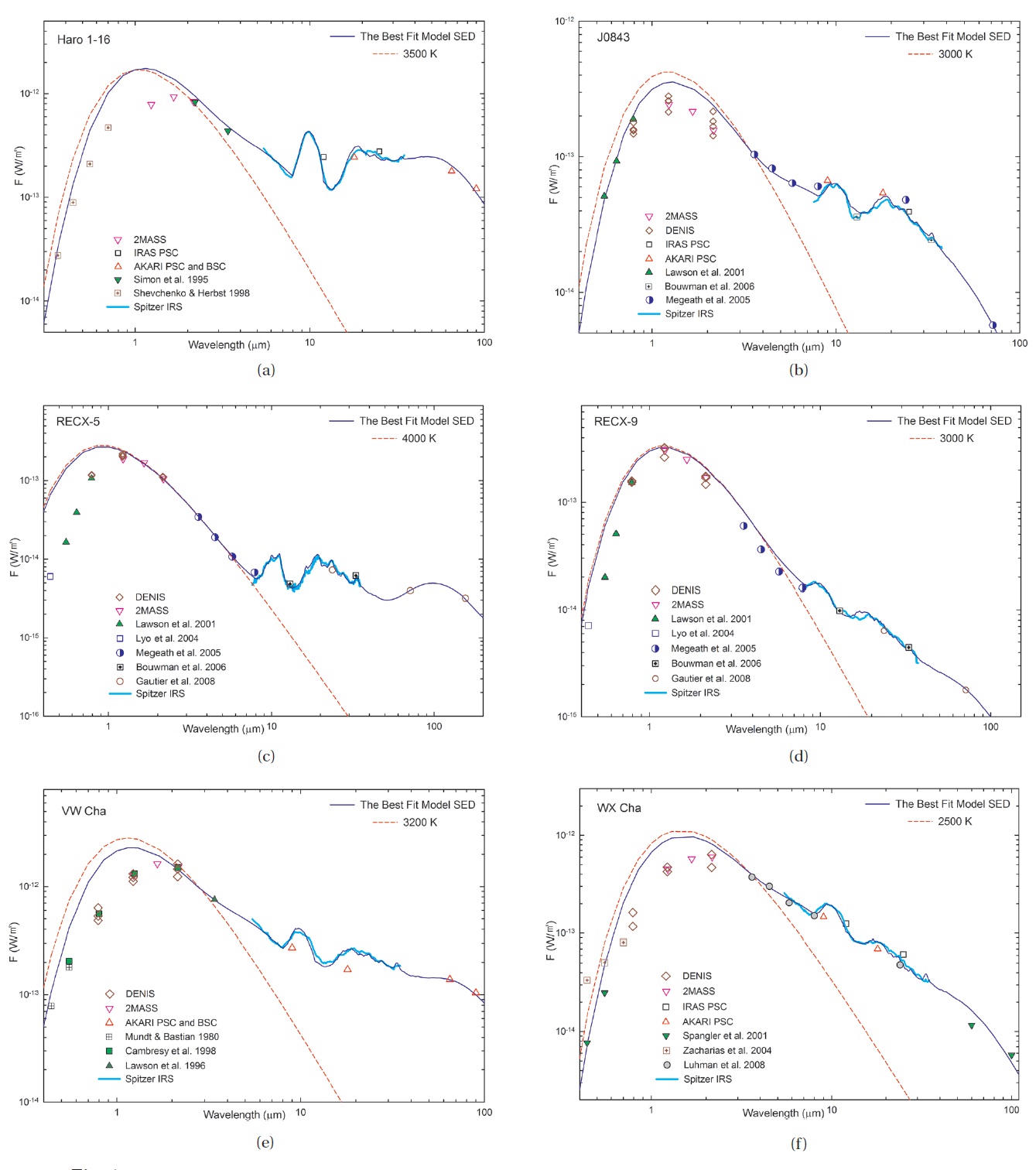

For amorphous silicate, we use the optical constants derived by Suh (1999) for cold silicate. For AMC, we use the optical constants derived by Suh (2000). For the two species, the extinction efficiency factors are calculated for

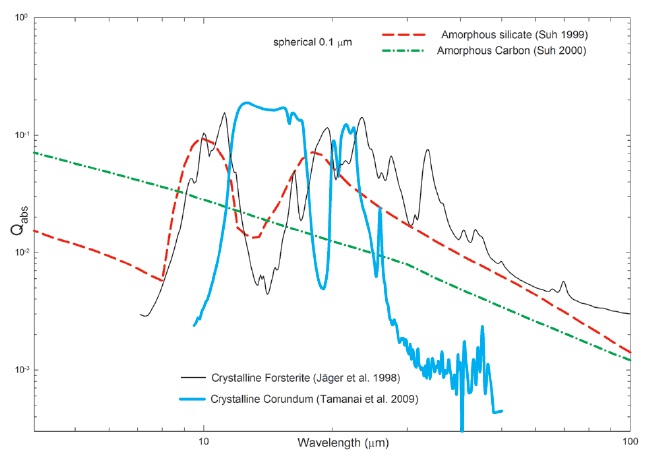

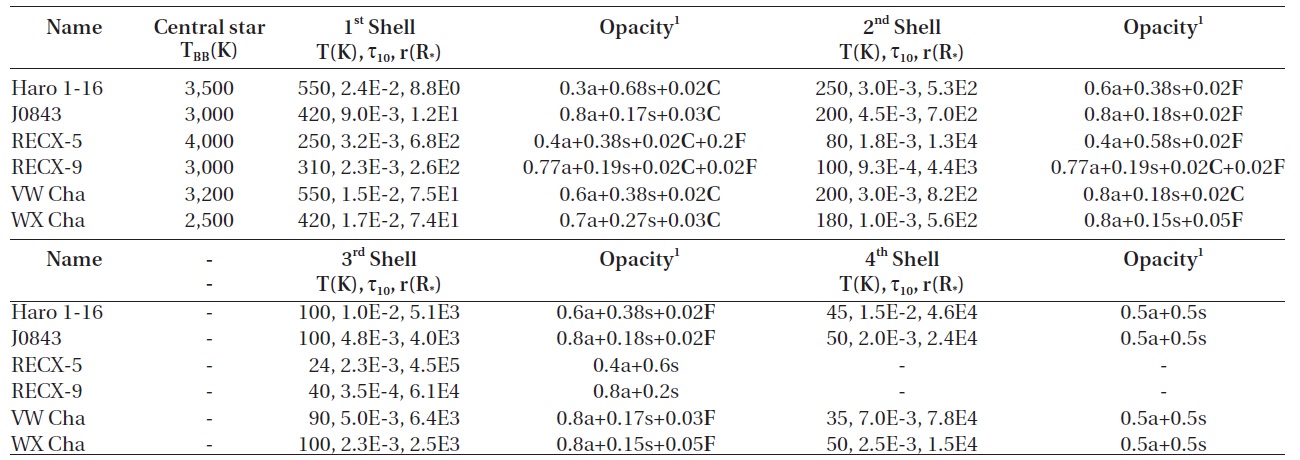

The model parameters of the multiple isothermal dust shells for the best fit model spectral energy distributions.

spherical dust grains (Bohren & Huffman 1983) from the optical constants given in the references. The radii of the spherical dust grains are assumed to be 0.1 ㎛ uniformly.

For crystalline corundum, we use the extinction data of α-Al2O3 (corundum-sample 1) obtained by Tamanai et al. (2009). For crystalline forsterite, we use the extinction data obtained by Jager et al. (1998).

Dust opacity functions for the four species are dis-played in Fig. 2. The crystalline forsterite grains produce conspicuous features at 10.0, 11.2, 16.3 19.5, 23.5, 27.5 and 33.5 ㎛. We had attempted to use other dust species (olivine, ice and oxides), but found they were not useful for this work.

We perform various radiative transfer model calcu-lations in the wavelength range 0.01 to 36,000 ㎛. We choose 10 ㎛ as the fiducial wavelength that sets the scale of the dust optical depth (τ10). We have computed the model SEDs for various optical depths of the multiple dust shells with different dust opacity.

For each object, we try to find the best fit model SED for the observations. Once we have a set of reason-able model parameters, we compare the model result with the observed SED and repeatedly revise the related parameter(s) until we get a satisfactory fit in the entire wavelength range. We may have to revise the parameters for the central star and the multiple dust shells repeatedly because of the correlated absorption processes.

The model parameters of the multiple isothermal dust shells for the best fit model SEDs are listed in Table 2. For each object, the parameters of the central star (the black-body temperature) and those for multiple dust shells are listed. For each dust shell, the equilibrium dust tempera-ture, the dust optical depth (τ10), the radius of the shell (r) in the unit of the radius of the central star (R*) and the dust opacity function are listed. All of the above param-eters are input parameters. For each model, the code cal-culates the radii of the multiple dust shells and the model SED.

The six panels of Fig. 1 show the best fit model SEDs compared with the observed SEDs for the six sample stars. For all of the sample stars, we use three or four separate dust shells with the four dust species (Table 2). We could reproduce some of the observed fine spectral features with the theoretical models using the crystalline dust grains. Generally, a cold (24-50 K) outer dust shell with amorphous silicate and AMC grains reproduces the FIR region fairly well.

Haro 1-16 shows very conspicuous amorphous silicate features at 10 and 20 ㎛ because of abundant (68%) sili-cate grains in the innermost shell. The model can repro-duce the evident forsterite dust features at 23.5 and 27.5 ㎛ and the vague feature at 33.5 ㎛. Crystalline corun-dum grains in the hot (550 K) innermost shell improve the fit in the 10-20 ㎛ region.

J0843 shows weak crystalline forsterite dust features and unknown features. The model can reproduce the evi-dent forsterite dust features at 23.5, 27.5 and 33.5 ㎛.

RECX-5 looks to have the hottest (4,000 K) central star. The object shows the most conspicuous crystalline for-sterite dust features in a wide wavelength range. Of the six sample stars, only this object shows the evident 10.0, 11.2 and 16.3 ㎛ features from hot forsterite. The star also shows the conspicuous 23.5, 27.5 and 33.5 ㎛ features. All of those features are reproduced by the theoretical model. The content of forsterite in the warm (250 K) in-nermost shell is very high (20%).

RECX-9 shows many weak spectral features in a wide wavelength range. Some of those features are unknown. The model can reproduce the vague forsterite dust fea-tures at 23.5, 27.5 and 33.5 ㎛. Crystalline corundum grains in inner two shells improve the fit in the 10-30 ㎛ region.

VW Cha shows weak crystalline dust features. The crys-talline forsterite grains that exist only in the cold (90 K) shell can reproduce the features at 23.5, 27.5 and 33.5 ㎛.

WX Cha shows very weak crystalline forsterite features. The crystalline forsterite grains in the two cold (100 and 180 K) shells produce the vague features at 23.5, 27.5 and 33.5 ㎛.

For all the sample stars, crystalline corundum in the hot (250-550 K) innermost shell improves the fit in the 10-20 ㎛ region.

Even though we have tried to reproduce all the features and characteristics of the observed SEDs by the radiative transfer model, we could not reproduce some of them (e.g., some features in J0843 and RECX-9). There are three possible reasons for this. First, we may not have consid-ered some important dust species. Secondly, the dust opacity functions used for this work may need to be im-proved. Finally, the radiative transfer model could be too simple. A more sophisticated radiative transfer model, which can consider multiple components of dusty disk and shell with more dust species, would be able to repro-duce the SEDs better.

The size of dust grains only affects the overall energy output in the far infrared region. We find that changes of the dust size do not cause meaningful differences in the overall fitting for the sample stars.

5. DISCUSSION ON CRYSTALLINE DUST

For all the sample stars, the observed spectral features of crystalline silicate (forsterite) grains are reproduced by the model calculations. Because crystalline silicate grains show very sharp features, even a small content (about 2%) can be easily detectable.

Though a small content (2-3%) of crystalline corun-dum grains does not reproduce their own sharp spectral features directly, those in the hot (250-550 K) innermost shell can improve the fit in the 10-20 ㎛ region for all the sample stars. Similar effects were found for some Herbig Ae/Be stars (Suh 2011).

It is quite evident that crystalline silicate (forsterite) grains exist in cold (48-100 K) outer regions of many T Tauri stars (this paper, Juhasz et al. 2010). Though crys-talline silicates are abundant in many young stellar ob-jects (YSOs) and solar system comets, they are essentially missing from the interstellar medium (Juhasz et al. 2010). It would be reasonable to assume that crystallization occurs in the low temperature envelopes (or disks) of YSOs.

Some known processes of crystallization (annealing and direct condensation from the gas phase) require high temperature (about 1,000 K) (Fabian et al. 2000). The vertical mixing by turbulence, in disks, can transfer crystalline grain components, which formed in the high temperatures and high ultraviolet radiation field of the disk atmosphere, into the disk midplane where the tem-perature is very low (Dullemond et al. 2006). Olofsson et al. (2009) argued that the abundant crystalline silicates found far from their presumed formation regions (hot regions) may suggest efficient outward radial transport mechanisms in the disks around T Tauri stars.

On the other hand, Carrez et al. (2002) and Kimura et al. (2008) suggested a mechanism of crystallization at low temperature by reporting that amorphous silicate grains were crystallized to forsterite by electron-beam irradia-tion. YSOs are known to undergo active and frequent flaring events in which electrons are accelerated. Therefore, the electron irradiation of dust in YSO environments could explain the origin of the crystalline silicate grains around T Tauri stars.

To reproduce the multiple broad peaks and fine spec-tral features in the SEDs of CTTS, we have modeled dust around CTTS using a radiative transfer model for mul-tiple isothermal circumstellar dust shells. By comparing the model results with the observed SEDs in a wide wave-length range for the six sample stars, we have presented the model parameters of the best fit model SEDs that will be helpful to understand the overall structure of dust en-velopes around T Tauri stars.

We have found that at least three separate dust compo-nents are required to reproduce the observed SEDs. For all the sample stars, an innermost hot (250-550 K) dust component of amorphous (silicate and carbon) and crys-talline (corundum for all objects and forsterite for some objects) grains is needed. We have found that crystalline forsterite grains can reproduce many fine spectral fea-tures of the sample stars.

A small content of crystalline corundum grains has been found to be present in all of the sample stars. Co-rundum appears to be one of the major dust components in YSOs.

For all the sample stars, the crystalline silicate (forst-erite) grains exist in cold (80-100 K) outer dust shells as well as in hot inner shells. Even though the reason for the existence of low temperature crystalline silicate is still un-certain, the electron irradiation of dust in YSO environ-ments or a process of outward radial transport could be possible scenarios.

Further investigations with sophisticated theoretical models using more various dust species could reveal use-ful information about the physical and chemical proper-ties of dust around T Tauri stars and the general environ-ments of star forming regions.