In the course of restoration in 2011 to its original form for the copy of 「the 1668

2. SEONGBYEON CHOOKHOO DANJA (星變測候單子) AND SEONGBYEON DEUNGROK (星變謄錄)

In the Joseon Dynasty, the observing staffs at the Astronomical Board (Gwansang-gam) made a report on unusual celestial and terrestrial event on their day or night duty to the Royal Secretariat (Seungjeong-won) without delay early next morning (Nha 1978). The one-page report in this process was called

[Table 1.] List of Seongbyeon Deungroks.

List of Seongbyeon Deungroks.

世宗 of Ming (明), and 世宗 of Qing (淸). Considering these aspects, we may say that it was natural and reflecting an advanced form of international relationship for the two countries to have used the same reign name together. Most countries use A.D. for their dating system these days, but it was only about 110 years ago, in the 33th year of Gojong (高宗), for Joseon to have adopted A.D., a result of the import of the Gregorian calendar.

The method of recording observed comets or guest stars in

3. RECOVERY OF THREE SEONGBYEON DEUNGROK (星變謄錄)

There are 8 books of

Over 40 years after the reports by Wada and Rufus on the eight

This recovery stimulated the society to search the remaining five

4. THE CONTENTS OF THE 7TH YEAR OF KANGXI SEONGBYEON DEUNGROK (THE 1668 DEUNGROK)

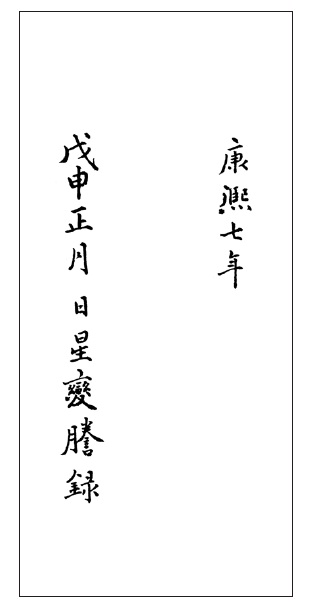

The title page and contents of the

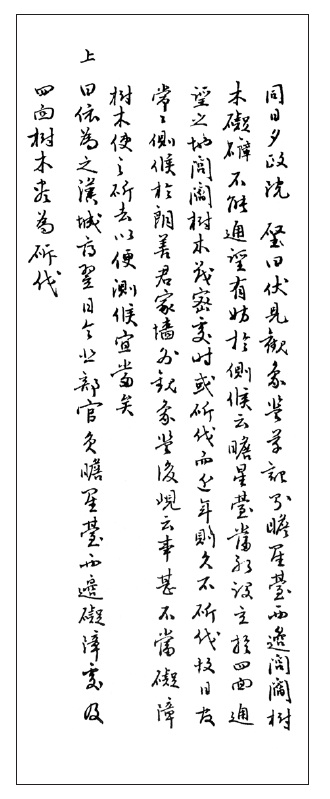

戊申正月日

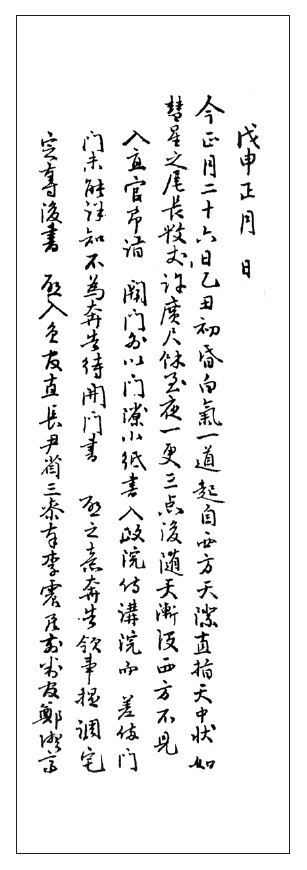

今正月二十六日乙丑初昏白氣一道起自西方天際直指天中狀如

彗星之尾長數丈許廣尺餘至夜一更三點後隨天漸沒西方不見

入直官卽詣闕門外以門隙小紙書入政院侍講院而差備門

門未能詳知不爲奔告待開門書啓之意奔告領事提調宅

定奪後書啓入直官直長尹省三參奉李震善前判官鄭德齊

English translation

On the 26th day, yichou [2], of this first month (of the 9th year of King Hyeonjong) (= 8 March 1668), at the beginning of dusk, one streak of white vapor arose from the western horizon and pointed towards the zenith. Its shape resembled a broom star and its tail was several jang in length and more than a cheok in width. When night came, after the third jeom [= division] of the first gyeong (= night watch), it disappeared in the west following the motion of the sky.

An official on duty deposited an observational report at the gates of the Seungjeong-won and the Sigang-won. When the gates were opened, Hui (a high-ranking official whose full name is currently uncertain) submitted the report to Yeongsa-Jejo (an official of highest rank). Officials on duty were Yoon Seong-sam, Yi Jin-ok and Jeong Deok-je.

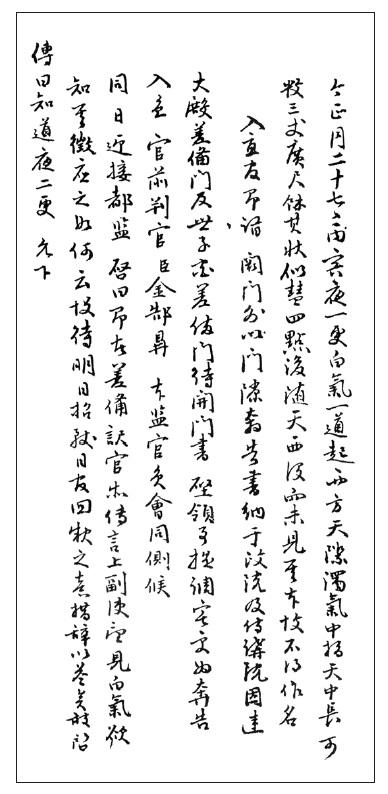

今正月二十七日丙寅夜一更白氣一道起西方天際濁氣中指天中長可

數三丈廣尺餘其狀似彗四點後隨天西沒而未見其本故不得作名

入直官卽詣闕門外以門隙奔告書納于政院及侍講院因達

大殿差備門及世子宮差備門待開門書啓領事提調宅更爲奔告

入直官前判官臣金?昇本監官員會同側候

同日迎接都監啓曰卽者差備譯官等傳言上副使望見白氣欲

知其徵應之如何云故待明日招致日官回報之意措辭以答矣敢啓

傳曰知道夜二更允下

English translation

On the 27th day, bingyin [3], of this first month (of the 9th year of King Hyeonjong) (= 9 March 1668), at night, in the first gyeong, one streak of white vapor arose from the turbid air on the western horizon and pointed towards the zenith. Its length was almost three jang and its width more than a cheok. After the fourth jeom it disappeared in the west following the motion of the sky. Since this type of phenomenon has not yet been seen before, it is impossible to give it a name.

An official on duty deposited an observational report at the gates of the Seungjeong-won and the Sigang-won. When the gates were opened, the report was delivered to Yeongsa-Jejo. The official Kim Go-seong made the observations along with other court observers.

On the same day, Yeongjeob Dogam (an official whose duty was to greet foreign ambassadors), was asked by a high-ranking official of the foreign representatives what kind of portent it could be. Yeongjeob Dogam replied that they should wait until next day and ask the staff of the Court Observatory.

At the second gyeong (20.7-22.9 h), his Royal Highness gave his assent.

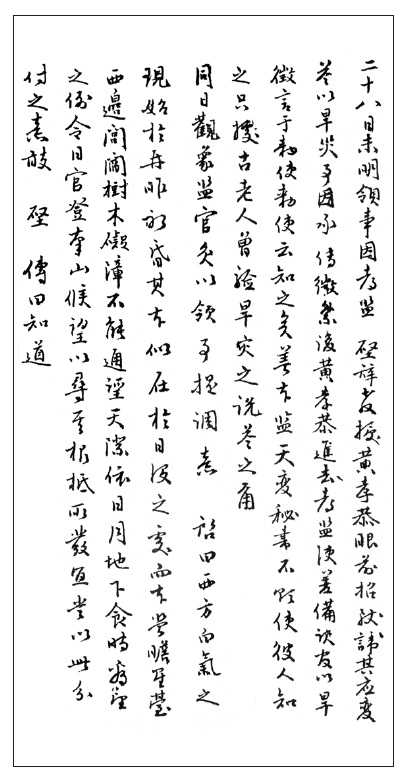

二十八日未明領事因都監啓辭敎授黃孝恭眼前招致諱 其應?

答以旱災事因承傳微稟後黃孝恭進去都監使差備譯官以旱

徵言于勅使勅使云知之矣差本監天變秘書不欲使彼人知

之只據古老人曾驗旱災之說答之爾

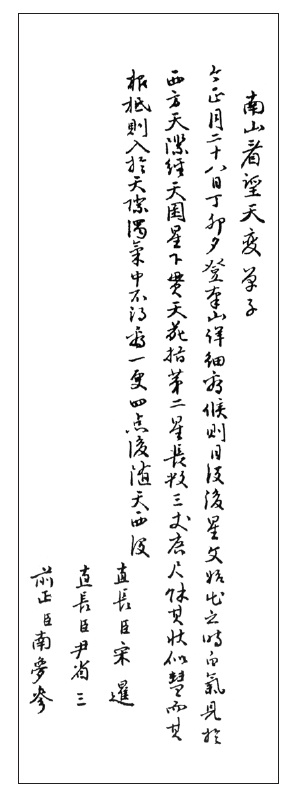

同日觀象監官員以領事提調意啓曰西方白氣之

現始於再昨初昏其本似在於日沒之處而本監瞻星臺

西邊閭閻樹木?障不能通望天際依日月地下食時看望

之例令日官登南山候望以尋其根抵所發宜當以此分

付之意敢啓傳曰知道

English translation

On the 28th day (= 10 March 1668), before dawn, a member of the Observatory staff Whang Hyo-gong was called to His Royal Highness and said that this (phenomenon) was a sign of drought. Whang Hyo-gong suggested addressing the foreign representative after the sacrifice. The foreign representative said that he was aware of it already. The Court Observatory staff expressed the wish that celestial portents should not be divulged to foreigners. The interpretation of this sign was based on the experience of an elderly man.

On the same day, Yeongsa-Jejo Hui said that the white vapor in the western direction appeared two nights ago at the beginning of dusk near the sunset point. However, trees of private houses close to the Observatory made celestial observation difficult. Therefore it was proposed to send observers to the top of Mt. Namsan to make their observation.

His Royal Highness gave his assent.

同日夕政院啓曰伏見觀象監草記則瞻星臺西邊閭閻樹

木?障不能通望有妨於側候云瞻星臺當初設立於四面通

望之地閭閻樹木茂密處時或斫伐而近年則久不斫伐故日官

常常側候於朗善君家墻外觀象監後峴云事甚不當?障

樹木使之斫去以便側候宜當矣

上曰依爲之漢城府翌日令北部官員瞻星臺西邊?障處及

四面樹木盡爲斫伐

English translation

In the evening of the same day the Jeongwon (the name of another office) reported to His Royal Highness with reference to a short report which had been received, stating that although the Observatory needed to have a clear view, the nearby trees obscured the view. These trees had not been cut back for several years, so that the observers made their observations at the house of Rangseon-goon (a grandson of King Seonjo). Therefore it was proposed to cut back the trees to facilitate observation.

His Royal Highness gave his approval to the Mayor. Next day, officials of the northern section cut back all the trees surrounding the Observatory.

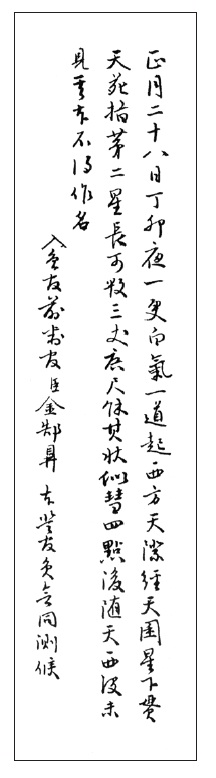

正月二十八日丁卯夜一更白氣一道起西方天際經天?星下貫

天苑指第二星長可數三丈廣尺餘其狀似彗四點後隨天西沒未

見其本不何作名

入直官前判官臣金?昇本監官員令同測候

English translation

On the 28th day, dingmao [4], of the first month (= 10 March 1668), at the first gyeong of the night, a streak of white vapor arose from the western horizon. It passed under (the constellation) Cheon-gun and pointed towards the second star of (the constellation) Cheon-won. Its length was about 3 jang and its width more than a cheok. Its shape resembled a broom. After the fourth jeom, following the motion of the sky it set in the west. Since this type of phenomenon has not yet been seen before, it is impossible to give it a name.

The official Kim Go-seong made this observation, together with other court observers.

南山看望天變單子

今正月二十八日丁卯夕登南山詳細看候則日沒後星文始出時之

時白氣見於

西方天際經天?星下貫天苑指第二星長可數三丈廣尺餘其狀似

彗而其

根抵則入於天際濁氣中不得看一更四點後隨天西沒

直長臣宋暹

直長臣尹省三

前正臣南夢參

English translation

Cheonbyeon

In the evening of the 28th day, dingmao [4], of this first month (= 10 March 1668), from the top of Mt. Namsan, after sunset and beginning with the first appearance of the stars, a white vapor was seen to arise from the western horizon. It passed under (the constellation) Cheon-gun and pointed towards the second star of (the constellation) Cheon-won. Its length was about 3 jang and its width more than a cheok. Its shape resembled a broom, but its head was invisible because of its location below the turbid horizon. At the fourth jeom of the first gyeong (20.0 h) it set on the western horizon. Since this type of phenomenon has not yet been seen before, it is impossible to give it a name.

The official Kim Go-seong made this observation, together with other court observers: Song Seom, Yoon Seong-sam, Nam Mong-sam.

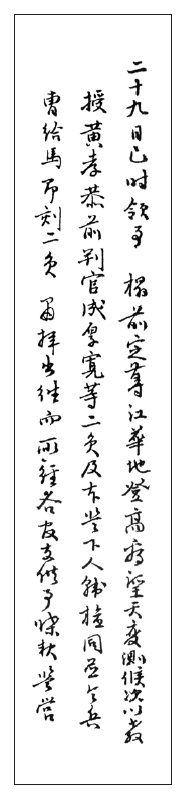

二十九日巳時領事榻前定奪江華地登高看望天變測候次以敎

授黃孝恭前判官成厚寬等二員及本監下人韓檀同竝令兵

曹給馬卽刻二員肅拜出 而所經各官支供事牒報監營

English translation

On the morning of the 29th day (= 11 March 1668), at the double hour si (= 9-11 h), the Director of the Observatory ordered two officials, Whang Hyo-gong and Seong Hoo-gwan, to jointly make observations on the mountain at Gangwha Island; they were to be accompanied by a servant, Han Geom. Now the Ministry of Defence offered horses for the two officials. They were also to be provided with necessities at the local stations on their way.

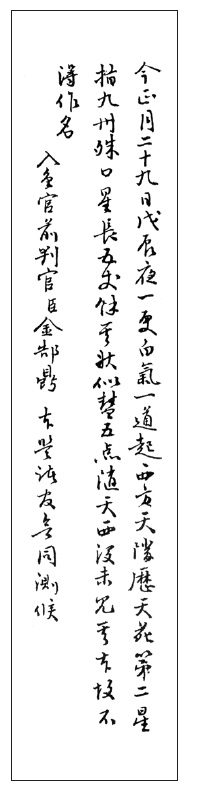

今正月二十九日戊辰夜一更白氣一道起西方天際歷天苑第二星

指九州殊口星長五丈餘其狀似彗五點隨天西沒未見其本故不

得作名

入直官前判官臣金?昇本監諸官員會同測候

English translation

On the 29th day, wuchen [5], of this first month (= 11 March 1668), at the first gyeong of the night, a streak of white vapor arose from the western horizon. It passed the second star of (the constellation) Cheon-won, and pointed towards (the constellation) Gujusoogu. Its length was more than 5 jang and its shape resembled a broom. After the fifth jeom it set on the western horizon. Since this type of phenomenon has not yet been seen before, it is impossible to give it a name. The official Kim Go-seong made this observation, together with other court observers.

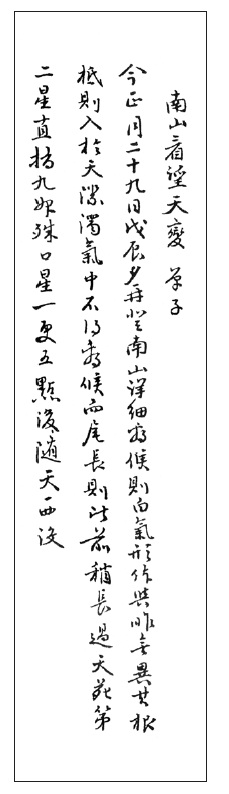

南山看望天變單子

今正月二十九日戊辰夕再登南山詳細看候則白氣形體與昨無異

其根

抵則入於天際濁氣中不得看候而尾長則比前稍長過天苑第

二星直指九州殊口星一更五點後隨天西沒

English translation

Cheonbyeon

In the evening of the 29th day, wuchen [5], of this first month (= 11 March 1668), (we) climbed up Mt.Namsan again and made observations. The shape of the white vapor remained the same as on the previous night, but its head was invisible because of its location below the turbid horizon. Its tail became slightly longer and passed the second star of (the constellation) Cheon-won and pointed towards (the constellation) Gujusoogu. After the fifth jeom of the first gyeong it set on the western horizon.

According to the text above, in the first day of observation, the observing staffs of Gwansang-gam named the observed celestial event ‘white vapor (白氣),’ but they called it a ‘comet’ at their report since they were not able to figure it out what the white vapor really was. However, they began to regard the white vapor as a strange phenomenon on the next day and then on. If this white vapor had been a comet, there should have been its head, but it was out of sight under the horizon. In their expression at that time, a head of comet was geunjeo(根抵, head). Thus, in search for the head of comet, they made efforts of cutting nearby trees to get better views to the horizon, and climbing up to the Mt. Namsan and even sending observing staffs to Ganghwa Island where the sight to the western horizon is guaranteed. However, they failed to find the head after all and made a conclusion saying “We are not able to name it since there has never been such a phenomenon as this.”

In the case that the head of comet is not seen even though its tail is long above the western horizon, the part of head might be located on the other side of the sun. Then, the head of this comet would be observable at the eastern horizon at dawn, instead of in the western sky in the early evening. However, they were not able to find the head in the east at dawn.

What indeed was this white vapor which they could not determine at that time? We introduce here another record from the Annals of Hyeonjong before continuing to the next section.

Jeong Tae-hwa, the prime minister, said secretly, “I heard that the Chinese envoy (北使) had noticed the extraordinary event of white vapor at night and today he was going to ask a staff of our Board of Astronomy about what this event would be an omen of. I am not sure what sign this extraordinary event is, but I suspect that it might be a portent of a war. As we cannot let the Chinese envoy (北使) know that as it is, it would be better to tell him that it is an omen of famine.”, but the king said “I don’t think we can hide the fact since they also have astronomers, but it is fine to talk to him based on what you said.” (Annals of Hyeonjong; the 28th day of the 1st month).

5. WHAT WAS THE WHITE VAPOR IN THE 1668 SEONGBYEON DEUNGROK?

Wada Yuji (和田雄治) is the first one who mentioned briefly the

Especially in the record of 「The 7th year of Kangxi」, “They cut the trees around Cheomseong-dae since the forest was thick and blocked the sight, observed at the summit of Mt. Namsan, and also sent an observing staff to Ganghwa Island for observations.” (omitted)

They found it in Europe on March 5 in that year, and it was a comet.

Now we examine the article of this

First, it cannot be a comet or guest star according to the expression in the record. It is because there repeats several times the sentence “而未見其本故不得作名” which means “Since this type of phenomenon has not yet been seen before, it is impossible to give it a name.” Among the observing staffs on that occasion, more than a few of them must have participated also in the observations of the great comet in 1664 which is a historical comet having appeared just four years before. And such observers confessed that they could not name it comet or guest star.

Second, it is stated that the tail was as long as five jangs (丈), and such a big comet cannot be imagined (Nha 1981). The greatest comet known so far is the one recorded in The 3rd year of Kangxi (康熙)

Angular sizes (角度) are used in principle for the length or width of a comet, but length units such as jang (丈), cheok (尺), or chon (寸) were used in the old literature. Converting those length units to angular sizes in degree (度) was done by Sekiguchi Rigichi (關口鯉吉), and he determined one cheok to be about one degree based on his comparison between comet drowings and records on length of tail (尾長) in several

Third, what seems even stranger is that the celestial event was expressed as ‘white vapor (白氣).’ There are some cases of writing color of a comet as ‘white’ but there is no other record of ‘white vapor.’ This ‘white vapor’ is certainly not a guest star. Guest star is a word for nova or supernova, but even the greatest supernova could not be seen as wide

spread as in this case. If it is neither a guest star nor a comet, then what is the ‘white vapor’?

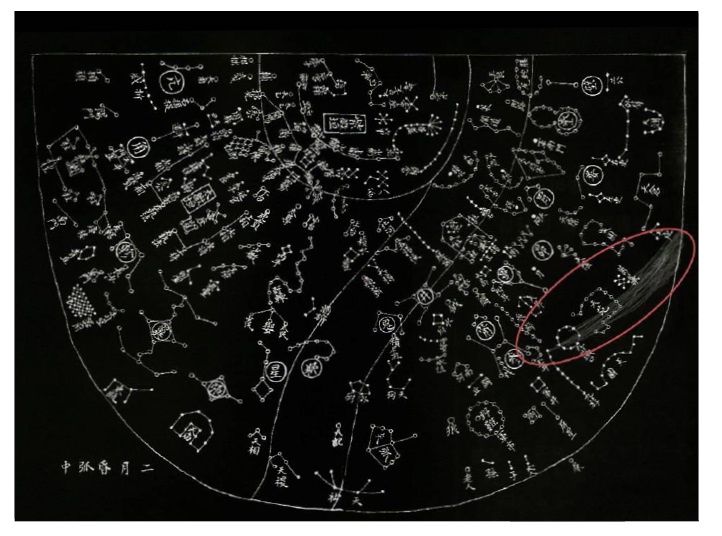

The position of the ‘white vapor’ is presented in the

Another star-map, the

Fourth, it is hardly probable, but could we assume that the ‘white vapor’ was an aurora borealis? As aurora is an atmospheric phenomenon observable around the poles of the earth magnetic field (地球磁氣), i.e. in high latitude regions near to the north pole. Scientifically considered, aurora is not observable in Hanyang (Seoul) even towards the lowest altitudes to the horizon. Furthermore, the strongest evidence against the assumption of aurora is the record that it was seen towards the western horizon (西方天際). If the ‘white vapor’ had been an aurora, it must have been seen towards the northern horizon, but there is no record in the

Records of the

Lynn (1882) re-examined several observing reports available in Europe on this ‘celestial event’. The observations were performed in 1668 in various places such as Lisbon, Cape of Good Hope, Goa, San Salvador, etc., but in his brief report, Lynn paid more attention to the observational record by Father Valentin Estancel (1674) at San Salvador. Some parts of Lynn’s article are introduced here as follows.

“The comet was observed for a few days, commencing on the 5th of March. He saw it in the evening, and was surprised to find it of extraordinary brightness when first seen, and then decreasing, instead of becoming brighter by degrees as he had noticed in other comets. As to the color of this comet, it was at first very splendid, but the brightness lasted only for three days, after which it did considerably decay. But that which seemed somewhat strange was, that having lost so much of its light, yet its bulk was diminished, but continued rather increasing until the comet disappeared.”

Lynn followed up with that the perihelion distance of this comet was reported by Henderson to be 0.25113 AU. Considering that the perihelion distance of Mercury is 0.307 AU, this comet entered into the orbit of Mercury.

There is another supporting article, and according to this

No details were provided, but later orbits indicated the comet was then in Cetus and it was probable that only the tail was seen. The comet had passed only 1˚.5 from the sun on February 29. -------------- Giovanni Cassini obtained his first observation on the 10th (= 28th day of the first month) during the first hour of the night and saw a “path of light” which he presumed was a comet, extending from Cetus through Eridanus. The tip of the tail lay near 14 Eridani, while the head was either hidden by “horizontal clouds” or still below the horizon.

(http://cometography.com/lcomets/1668e1.html)

The above statement, ‘he

Also in China, there are records of celestial events written in a period close to the occurrence of the ‘white vapor.’ Here we count dates on the solar calendar. First, there is a record on a comet from January 14 to February 11 in 1668 (Beijing Observatory 1989a), but this has nothing to do with the ‘celestial event’ in question. The second record was made after about one month, on March 2, 1668. It says ‘A comet appeared at night in the west. The length of its tail was a few jangs, and it disappeared after several days’ (Beijing Observatory 1989b). This is clearly a record of comet. However, also in China, there are more than a few dozens of observing records on ‘white vapor’ and ‘black vapor (黑氣)’ during the same period. The first one on March 3 says ‘Vapor appeared in the west, which was red then looked white. The bottom of it was ‘black vapor’ and its shape is similar to a cloth (布)’ (Beijing Observatory 1989c). After this record, there are a number of records from March 6 using only the term ‘white vapor.’ Two examples are as follows. ‘(March 6): White vapor appeared with a shape like white silk (煉), which passed through the southwest and pointed straight to the northeast’ (Beijing Observatory 1989c) or ‘(March 7): White vapor like a spear (槍) appeared in the west at the 19th of the 24 periods of the day, and black vapor like a sword (刀) with three blades appeared at the night of 27th day’ (Beijing Observatory 1989d). Such Chinese records are interesting, but on the other hand, are difficult to interpret since they did not describe the shapes and positions scientifically, not like the records by the observing staffs at Gwansang-gam of Joseon.

Now we return to the records in Joseon. In addition to the

1) On the 4th and 5th days of the second month in the 9th year of Hyeonjong, the expression of chiugi (蚩尤旗)’ was used. This is an expression for a comet splitting into two tails.

2) On the 4th day of the second month in the 9th year of Hyeonjong, an unbelievable tail of 7 jangs long, which was longer than 5 jangs in the Deungrok, was observed.

3) On the 5th day of the second month in the 9th year of Hyeonjong and several days afterward, a ‘light’ was introduced as ‘vapor like fire light (有氣如火光).’

Except for 1) above, those records are against the assumption of comet. Therefore, it is clear that the 1668 celestial event is a new sample for studies on the solar activity and abnormal phenomena of the earth atmosphere. It might be such an important discovery in the ancient observing records in China, Korea, and Japan as the facts that sunspots were observed with the unaided eye and that guest stars were supernovae which made significant impacts on modern science.

As briefly mentioned earlier, there is an interesting article in the

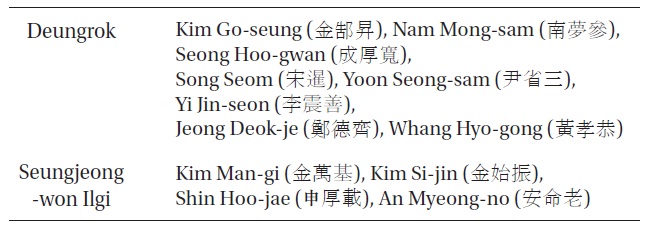

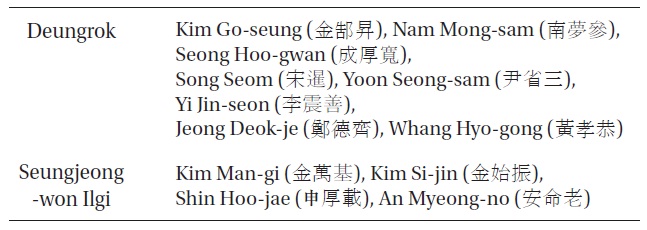

[Table 2.] Names of the 12 Chookhoo-gwan (測候官, astronomers).

Names of the 12 Chookhoo-gwan (測候官, astronomers).

Cheomseong-dae is now clear considering that he lived in this North Gwangwha-bang.

The recovery of the 12 observing staffs in total is also a significant result. Among them, 8 were found in the