1. INTORODUCTION ? SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY PARKS ? AN EVOLVING MODEL

Initially science parks were developed as sites on which to locate large corporate R&D centres close to a host organisation such as a university and that this co-location would result in the exchange of ideas and produce innovation. The realization of the need to accelerate the rate of innovation by the businesses on these sites resulted in putting management systems in pace to support linkages between tenant companies and host organisations and to develop business incubation programmes. Over the last 15 years the idea of regional innovation systems have also been developed and implemented in a further attempt to increase the rate of innovation by businesses. The key feature of these systems is the implementation of policies which: increase the rate of knowledge and skills generation; improve the capacity of business to absorb these two resources; increase the rate of diffusion of ideas that can influence business development across a region; and improving connections to markets for the businesses that are active in the system. Many countries are now using science parks and their respective host organisations as key parts of the infrastructure to support these innovation systems(Parry 2006).

This transformation has involved developing a number of strategies. These include: improvements to the supply of ideas from the discovery phase in science, technology and engineering in the context of their potential for commercialisation; the refinement of the range of business development programmes on offer which include pre, full and post incubation activities; and the integration of these activities on a larger scale across a wider physical region by influencing the key components in the supply chain that link the ideas to the market.

The value of science and technology parks is that they create a focal point that, if effectively managed, provides the three critical stakeholders of business, knowledge generators and government with an environment in which they can express their own value propositions in an attempt to create new innovation led businesses.

The main value proposition of each of these stakeholders is respectively economic development for government, gaining a competitive advantage for tenants, and technology and knowledge transfer for hosts. To deliver these propositions governments have tended to put policies in place to encourage business, technology and social environments that support innovation, businesses have looked to find technologies and skills that that are beyond technology readiness levels 6, and genera-tors of knowledge have begun to adapt to supply the skills and technology that are demanded by business.

2. RESEARCH DESIGN AND DEFINITION PERFORMANCE OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY PARKS

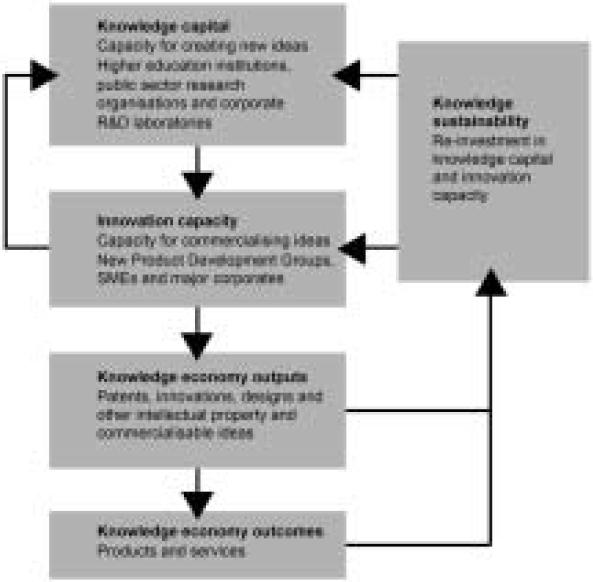

A study of the performance of companies on science parks undertaken by the UK Science Park Association and the UK Government’s Small Business Service, in 2003(UKSPA and SBS 2003) noted that science parks that operated in regional environments that provided all the elements and connections noted in Fig. 1 were more successful than those where the linkages were either missing or not functioning.

The importance of this finding is that managers of science parks need to understand where capacity is missing and find ways of filling these gaps by developing appropriate networks, linkages and encouraging government to establish appropriate policies that support these connections.

In these regions knowledge capital comes from a wide range of organisations. These include universities, public sector research organisations, corporate research laboratories and private contract research organisations. One of the roles for science parks is the active management of the relationships and links between these organisation in order to encourage technology transfer.

To take advantage of the ideas that emerge from these generators requires innovation capacity in the region that is capable of developing and commercialising new products. This capacity derives from a number of organisations that include:

Small, medium and large enterprises in the region that are driven to improve their competitive position in the market place.

Groups concerned with new product development such as designers, contract research organisations, consultancies, and business development teams.

Organisations which understand the creative process of entrepreneurship which helps to wrap ideas in an attractive way that encourages customers or buyers for the outputs.

Active engagement between customers and suppliers in supply chains to help to drive utilisation of new ideas.

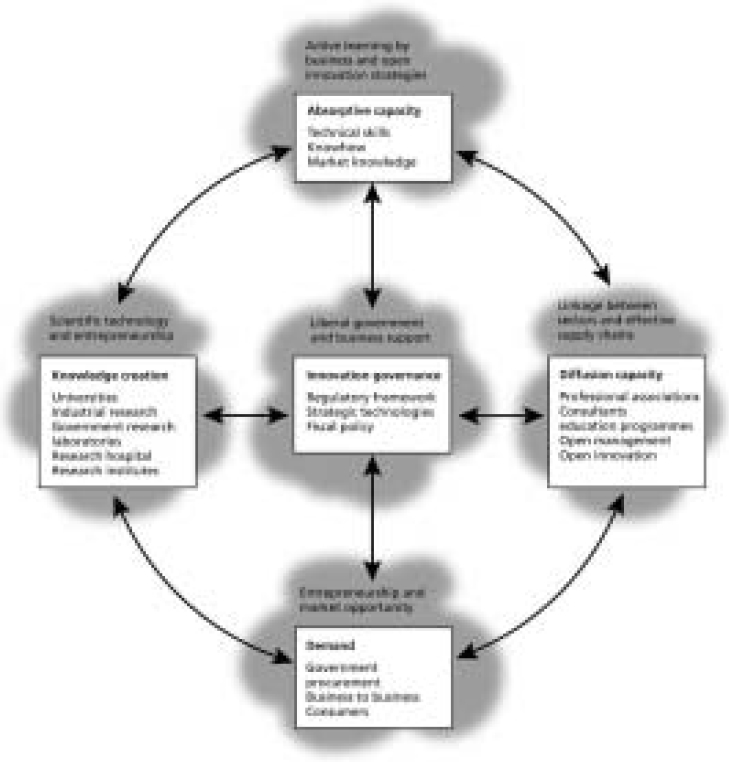

When science parks were first established the potential of these networks was not fully appreciated; however, the value of these linkages is now recognised and this has prompted the development and implementation of regional innovation systems. These systems use active management, policy frameworks and interventions to try to ensure that the necessary linkages that connect supply and demand are created and each element operates to its full potential. These elements are characterised in Fig. 2.

The functional elements of this are: the connections between knowledge creation and the market by encouraging the wider use of skills to absorb ideas for commercialisation; helping to diffuse ideas into a wider target group of businesses; and using policy instruments, deregulation and investment in infrastructure to encourage demand. Examples of the latter of these elements include: implementing high speed broadband, de-regulation of technologies such as genetic modification, telecoms and stem cell research and developing e-government. These relationships are described in Fig. 2.

In this process the production of new ideas and the availability of human capital that can interpret ideas and technologies and translate them into a business model, needs to be in place. Without this capacity to absorb ideas some of the steps in the technology, company, or market journey which make up the commercialisation process are more difficult to achieve. The process then relies on the ability to diffuse the ideas from these generators into the business community and society and finding markets that are prepared to utilise the outputs.

Experience has shown that science parks and their host organisations can play a central role in these systems. Factors which help to give this lead to science parks include: their brand value; the support they receive from their stakeholders; the presence of on-site management and the capacity this provides for developing networks: and their pre and full incubation activities.

Today with shrinking public sector funding available for general business support government is looking for efficiencies in their spend but still want to realise their value propositions for science parks. This shift in the balance of public expenditure provides science and technology parks with an opportunity to establish and maintain the role of leadership in supporting innovative companies.

One option is for the largest park in a region to provide a central management support programme for the smaller parks in their region. This is likely to require modern video conferencing systems to link all the parks in a region to provide common business development and education programmes.

Innovation governance, which lays at the heart of all innovation systems, is important for creating the optimum macro-environment that supports business formation and development. Important in this environment include: creating a good tax environment for investors in companies whether they are active in the management of the company or external investors; making funds available to support the stages of the technology, company and market journeys; establishing a supportive regulatory environment; removing state run monopolies that stifle competition; and helping to create markets as part of wider procurement policies.

The importance of innovation dominates much of the discussion, literature and policies about economic development. The importance of this process is the direct impact it has on the performance of firms or social institutions(OECD 2005).

In this context innovation can range from small changes which are incremental in nature but still lead to a commercial organisation maintaining a competitive advantage, through to changes which are disruptive which can be very damaging to some industries while launching others. Innovation can also have a regional context and can be used to describe the introduction of new ideas to a region or country, which may already be prevalent in others and in some instances, can be used as a foundation for autarky. Although the term innovation is most often applied to commercial success arising from technology it can also be achieved in relation to both trades and services as well as changes in government programmes that can lead to significant wealth creation.

The response to these changes or disruptive influences requires those industries under threat because of innovation by their competitors to themselves innovate in order to survive. Although the need to innovate is widely accepted as important the necessary business practices that encourage successful execution of the process needs to be more widely adopted by business if they are to maintain or extend their competitive advantage.

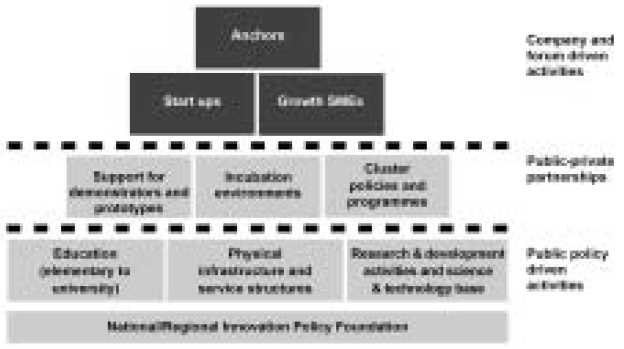

To understand how to encourage a more widespread adoption of innovation related business practices has led to extensive reviews of the dynamic of the processes. One of the conclusions is that external economic, social, business and technology related conditions are an important influence. The current view is that these conditions can be most effectively created through active public ? private partnerships that bring together a number of interconnecting elements which are characterised in Fig. 3.

The current consensus is that drivers that combine to create this environment and push this system require public sector policies and associated investment in education, infrastructure and knowledge generation (R&D). The next level of policy and investment needs to encourage the formation of public - private partnerships which share the risks of further development of the outputs from this process. Diminishing risks are eventually perceived as acceptable by the private sector and at that stage the balance of public engagement in the partnership fades significantly; although this element can never disappear completely because they still have to operate in regulated environments.

For the relationships that make up this process to most effective there needs to be structures, mechanisms and instruments that enable the transfer of ideas and the risk associated with their development, between each level. Pre and full business incubators are now commonly adopted as part of the infrastructure that supports the initial handover from being supported by the public sector to entities that are supported by public-private partnerships. Most innovation systems also offer funding for setting up demonstrators and where appropriate creating prototypes. If policies are put in place to support the formation of clusters of companies that share the risk of developing ideas, as part of the commercialisation process, this can help to accelerate economic development.

The process of testing ideas in the market place, and if they have commercial potential, mobilising the resources to support the delivery of the output (goods and services) to the market requires a mix of micro, small, medium and large companies to be actively engaged in process. Science and Technology Parks have proved that they are effective in both coordinating the efforts of government, academia and business in both enabling the public-private partnerships and the company and forum activities characterised in Fig. 3.

Factors which have proved to be of value in making such a system work include:

Collaborative relationships which are normally developed through an iterative process that link public and private organisations in complex arrangements which provide infrastructure and business support programmes.

Creative business practices between knowledge generators and knowledge users that drive technology, company and market journeys.

Experienced people that can appreciate both the value of technology in a commercial context and have the skill to support the transfer of the technology from the domain of creation to the domain of its utilisation to realise a competitive advantage.

A funding regime that slowly decreased public involvement in R&D and increases the private sector funding.

The patience to build the necessary systems over a time horizon of 10 to 20 years rather than simple, often politically driven, short terms horizons: this time horizon is particularly important when benchmarking the impact on the economy of science and technology parks.

The influence of competition that provides the incentive which gives impetus, through technology push and market pull.

The incentives to the public sector government to support these stages include stability that comes with creating high value employment, tax generation to sustain and grow the process, and the creation of wealth and prosperity.

3. FUNCTIONAL LINKS ON SCIENCE PARKS CONCERNED WITH CAPACITY BUILDING AND SUPPORTING INNOVATION

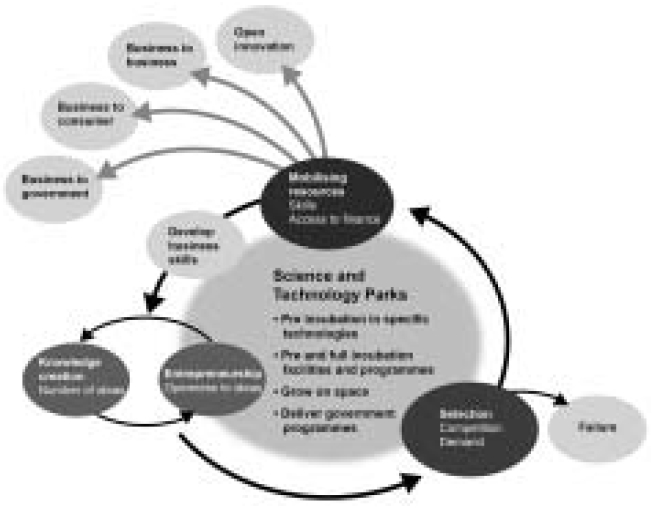

A macro view of the process that is supported by science and technology parks is characterised in Fig. 4.

The elements, activities and linkages characterised in this figure put science parks outside the domain of main stream knowledge discovery. The bulk of the work by the companies on science and technology parks is to support entrepreneurs while they take their ideas through a selection process that identifies those ideas deemed to have low commercial potential and leaves those with some perceived value for further development and tries to help these latter companies by mobilising the necessary skills and finance to get to market. The intention of this process is to build businesses that address potential markets. A secondary effect of this process is that the skills developed in the process, even when ideas are not successful are either retained in one location or recycled back into the business community to support further iterations of the process.

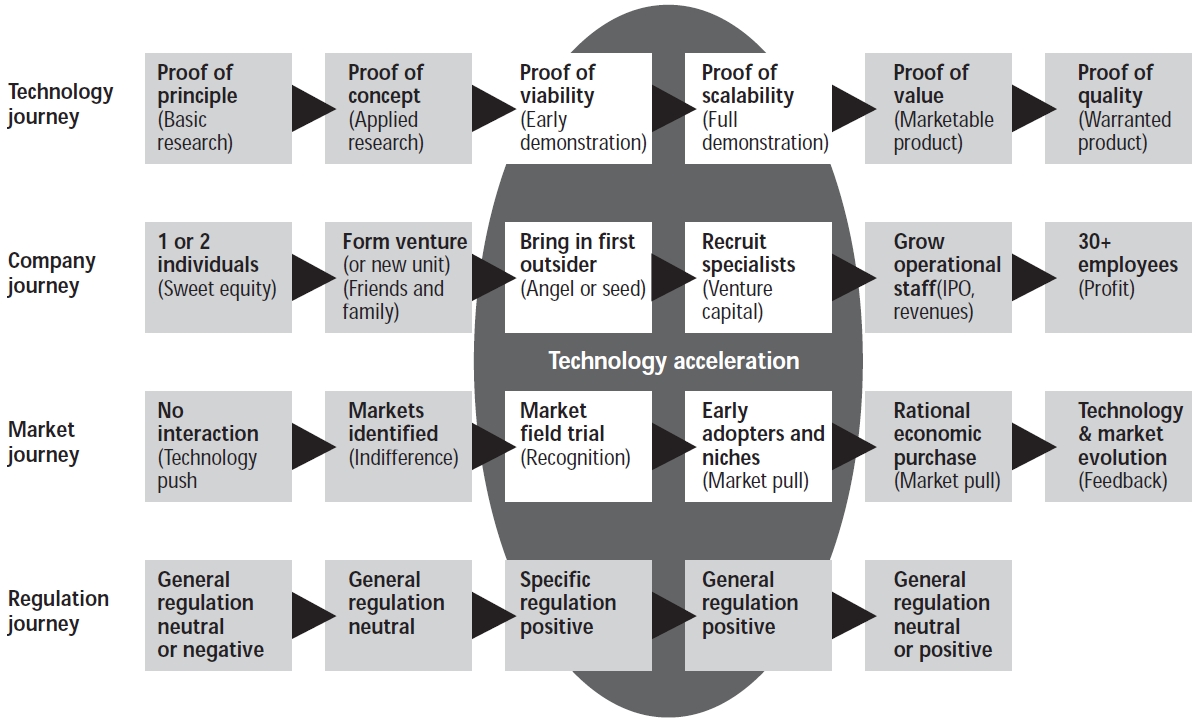

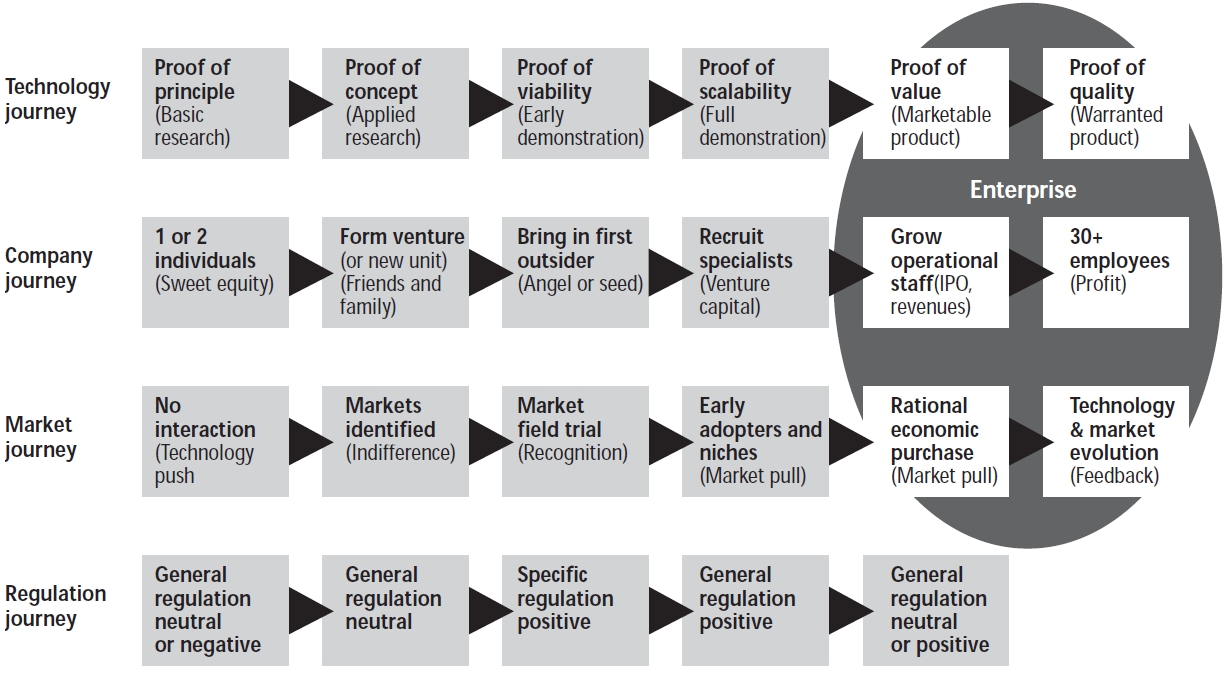

Underlying these functional links are a series of technology, market and company journeys(Parry 2008) which if successfully executed lead to an increase in the number, size and efficiency of companies in a region.

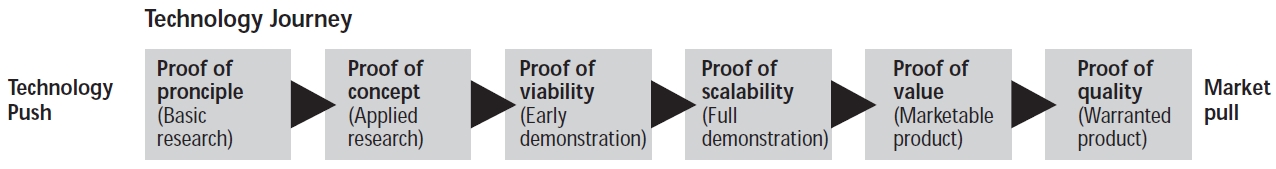

The importance of the technology journey is that it underpins innovation. From the perspective of operators of science and technology parks it is important that there is a supply of entrepreneurs capable of absorbing the ideas and appreciating the value of these in satisfying a real or perceived customer requirement. This may result from a response by an entrepreneur to a technical specification which pushes technology towards a market or appreciation of a market by an entrepreneur who then interprets the technical specification behind the idea and then pulls this towards the market.

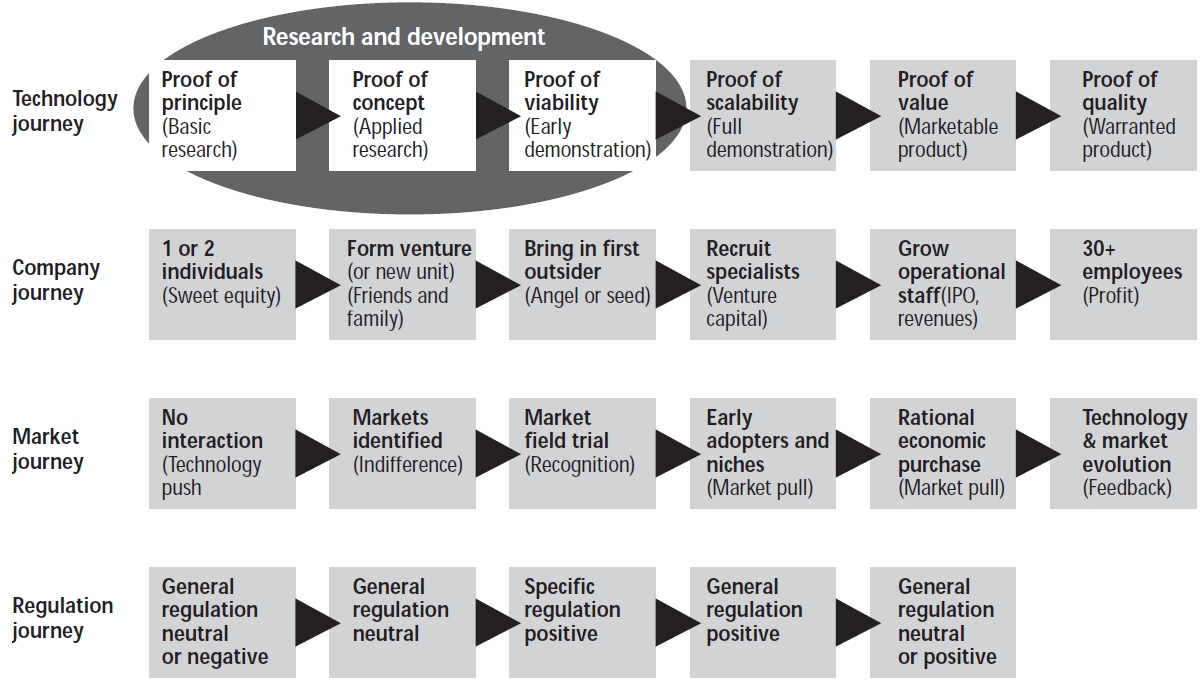

This technology journey can be characterised in the following way (Fig. 5).

Although some ideas that are taken along the technology journey the majority emerge from the general business commu-

nity rather than from knowledge generators such as universities, government research laboratories, and research hospitals.

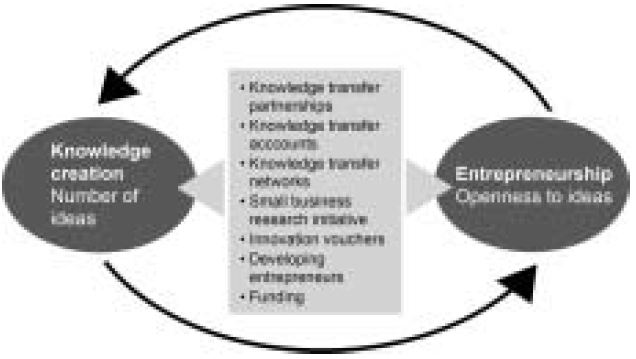

Experience suggests that to increase the number of ideas being commercialized and the rate of commercialization there needs to be in place a range of technology transfer programmes. A number of examples of these are described in Fig. 6.

Examples of policies and policy instruments in the UK which support the connection of technology to the market include:

These are aimed at helping businesses improve their competitiveness and productivity by using knowledge, technology and skills in the UK knowledge base.

The benefits for academics that are engaged in these programmes include, keeping them up to date with commercial needs; helping them work on real business problems and helping them find new research themes for undergraduate and postgraduate projects. Business also gains by having access to skills and expertise for business development.

The kind of projects KTPs support include product design and development, developing manufacturing practices and management processes or working on computing or management information in order to solve problems through innovation.

These are funded by the UK government with the view to supporting specific skills from a particular university’ s expertise. Examples include accounts in nanotechnology, photonics, communication and signal processing, and next generation materials and characterization. The purpose of these is to help match outputs and capabilities from universities with industrial needs, provide access to funds for pilot and demonstrator programmes, and increase the speed and reduce the costs for access by business to university facilities in order to support innovation.

This programme is also available to support spin out companies that may have been created within a university. They have particular value in supporting demonstrator programme that are concerned with bringing technology closer to the market.

In the UK there are currently (2011) 16 KTNs which operate in specific fields by linking people who are concerned with driving a specific technology across industrial sectors and encouraging commercially based solutions to be founded by companies.

This programme supports the need for the UK government to reduce the cost to the public purse of R&D. It has been organised to help early stage high-technology Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) gain greater access to Research and Development (R&D) opportunities while supporting the future procurement needs of Government Departments by offering competitive R&D contracts that aim to:

Provide opportunities to those existing small firms whose businesses are based upon providing R&D - by increasing the size of the market.

Encourage other smaller businesses to increase their R&D capabilities and capacity - to exploit the new market opportunities.

Create opportunities for starting new technology-based or knowledge-based businesses.

Part of the thinking behind the SBRI is that it enables government departments and other UK public sector organisations to procure new technologies faster and with managed risk through a phased development programme, and it provides paid contracts for the critical stage of product development.

These vouchers are aimed at small and medium-sized businesses to help them buy support from an academic institution of their choice to explore potential opportunities for future collaboration.

Ideas which need to be developed include:

International connections for ideas ? building international technology networks that focus on a single sector to try to increase the intensity of commercialisation of ideas by cross licensing arrangement and broadening the exposure of the ideas to the early stage equity market.

Building networks that connect corporate venturing activities to pre and full incubation programmes.

Helping governments deliver funding programmes to high growth companies that are active in technologies that are a national priority.

The presence in a business community of technology entrepreneurs is a critical ingredient in driving innovation. If there are high numbers of entrepreneurs with a broad range of skills that are able to both identify business models to develop technology for the market and wrap the right skilled workforce around the technology the greater the chance of success.

Ideas that are now being supported by science and technology parks to help encourage entrepreneurship include entrepreneur clubs which are now common in universities, an increasing number have appointed an “Entrepreneur in Residence” to work in both science and technology parks as well as University Business Schools. Both are active in the University of Surrey’ s Business School and the Surrey Research Park.

A model for funding technology transfer that is gaining momentum in the UK is based on a contractual relationship between a host organisation and private equity capital group. Around 10 universities in the UK have signed such an exclusive arrangement with the IP Group. The business model values the IP at a pre-determined value, the IP Group take an agreed proportion of this and then work with the IP to develop its commercial potential.

A similar programmes associated with government research laboratories has been established through a privately managed evergreen fund (Rainbow Fund) that provides support to ideas which have commercial potential.

Today there is increasing emphasis on funding R&D that has a strong orientation towards potential commercial value. This direction when associated with the cultural change engendered by the presence of a science and technology park on a campus helps to increase interest in the commercialisation of new ideas.

Although there are still relatively few companies being spun out from universities the professionalisation of the work of Technology Transfer Offices in the higher education sector through training and provision of funding to support technology commercialisation means it is likely that this will eventually lead to this occurring on a larger scale.

The role of science parks in the technology journey is aimed more towards supporting the downstream commercialisation phases rather than in the discovery process. This means that parks have to be more active in mobilising the resources to drive the market and company journeys rather than technology journeys, although this cannot be ignored.

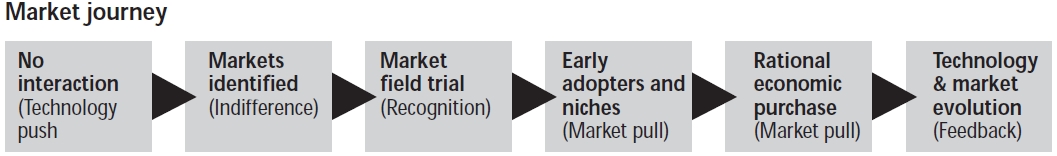

A full market journey for technology takes the market from complete indifference to widespread adoption. Of course not all technologies start at the beginning of this continuum and not all end in wide spread adoption. Experience has shown that some are taken out of the market by acquisition before they are become fully fledged technologies.

The critical ingredient in this journey is the skills and flair of the entrepreneur. This comes from a combination of the entrepreneur’ s understanding of the market place, recognition of how this market would benefit from the technology and ability to organise the development of the market.

However, there are support programmes which can help with working along the process. These include:

Providing funds to create demonstrators for field trials.

Using networks to link companies still in incubation with larger companies looking to gain access to ideas through open innovation strategies.

Using networks on and between science park to connect companies across wider sector groups.

Taking an active role in promoting and supporting companies as they link into Knowledge Transfer Networks or their equivalent.

Creating connections that bring into the network international equity finance that helps to widen the exposure of ideas with commercial potential to an international market.

Using their connections to promote companies through international trade support channels such as trade missions, commercial attach?s, and other science parks with which they have contact.

Connecting companies and government services that help to provide market intelligence. In the UK a num-ber of programmes are available that can be used to provide this information.

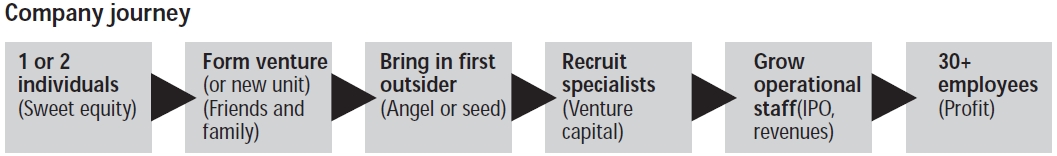

One of the most common patterns for a company journeys is characterised in Fig. 8. This usually starts with 1 or 2 individuals and numbers of employees are added as new dimensions to the business need to be explored and developed. In the case of spinout companies these individuals are often technology entrepreneurs. As the company develops the team needs to be supplemented with a wider range of skills. Most commonly the initial increase in skills comes from investors.

Recruitment of the right people on which to base a team is one of the most critical aspects of building companies. Many science parks have networks of contacts that can be used to help to identify potential employees.

High growth coaching has particular value when staff numbers have reached more than ten. Some examples of the kinds of programmes that have been put together in high growth coaching to support the market journey include:

Finance for Growth ? this provides advice on the basics that every business leader should know in managing a growing business effectively and includes details on raising finance.

Market intelligence - how to increase or better organise company awareness of current and potential markets by developing a marketing intelligence strategy.

eMarketing and eCommerce - to facilitate the widest possible use of the tools and techniques made available by the e-revolution to open up new sales and marketing opportunities.

Out-thinking the competition - advanced creative techniques to give companies the edge through enhanced decision-making and improved leadership capabilities.

Building the innovative organisation - to demonstrate how fundamental improvements in organisational behaviour can embed innovation in all aspects of a successful business activities and how to protect the results.

Improving selling skills - to help improve understanding of the sales process and the development of personal selling skills across senior management

Leading and managing high growth - training for senior managers who have had little previous formal training and lack the leadership and management expertise to sustain growth

Change management - implementing change at middle management level is a major concern in growing companies. This proven change management training helps middle managers deal effectively with change

Management information healthcheck - an audit of a company’ s current management information, followed by a written report on the potential management information needs of the business as it grows.

Providing these programmes through third party contractors that work across regions can help to keep cost low while helping to up-rate a region’ s innovation capacity.

Many new ideas have emerged following the liberalisation of markets and de-regulation. In addition but conversely a number of new markets have emerged as there is increasing control over some aspects of human endeavour such as property development and the need for increased control over the environmental effect of these endeavours.

Many new companies need to be cognisant of both the opportunities changes in legislation and regulation can create.

Two examples of deregulation that has driven entrepreneurship include those in the telecoms sector and secondly the bio-technology such as allowing stem cell research. In contrast the need to test the environmental impact of property development has created an industry which employs ecologists to undertake relevant environmental impact assessments.

Most regulations are promulgated by governments. Today details of the these regulations can be found on such sites as Netregs for the UK’ s regulations on the environment and other business support sites such as Business Links.

One of the roles of science parks is to know how to guide companies in interpreting these regulations.

The process of pre, full and post incubation is an area in which science and technology parks are continuing to evolve

and develop new ideas.

Some examples for opportunities for pushing the boundary for science and technology parks include:

Professionalising this process.

Concentrating resources in one location and then operating across a network using the professional skills to support the process in a number of locations. There are strategies which can be adopted by science and technology parks in order to create this concentration of activity. These include:

Pricing for accommodation and services.

Increasing the opportunity to gain access to development finance.

Providing access to support programmes.

Supporting companies gain access to market related networks.

Developing specialisms in relation to supporting specific technology sectors.

Developing working relationships with private sector groups to help develop companies.

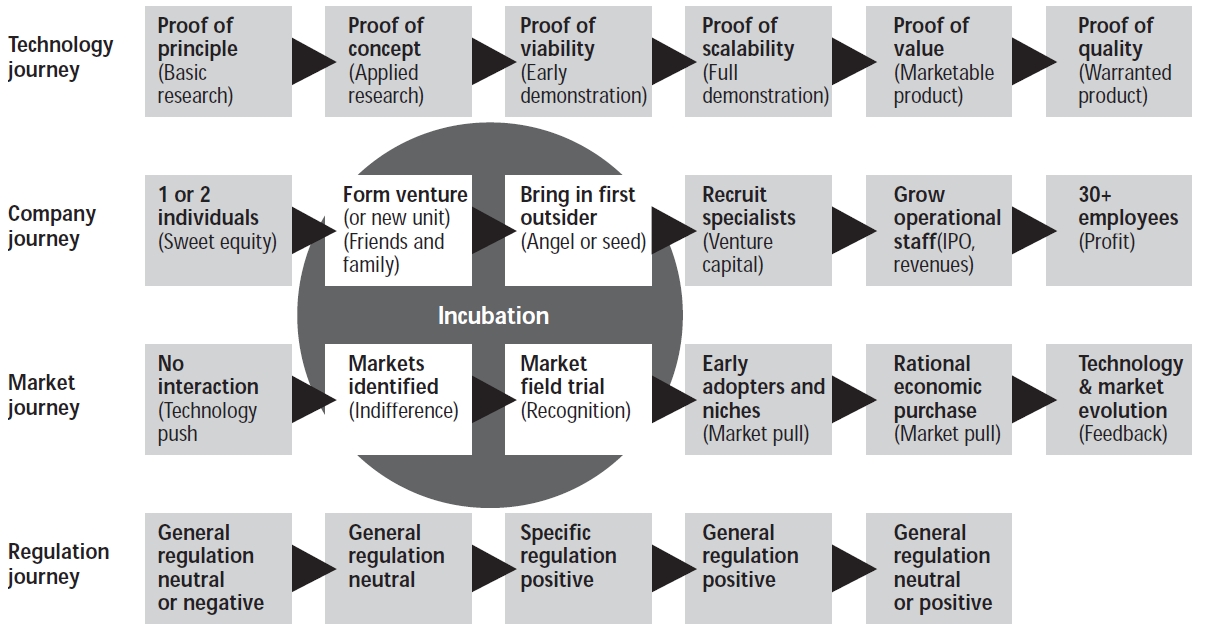

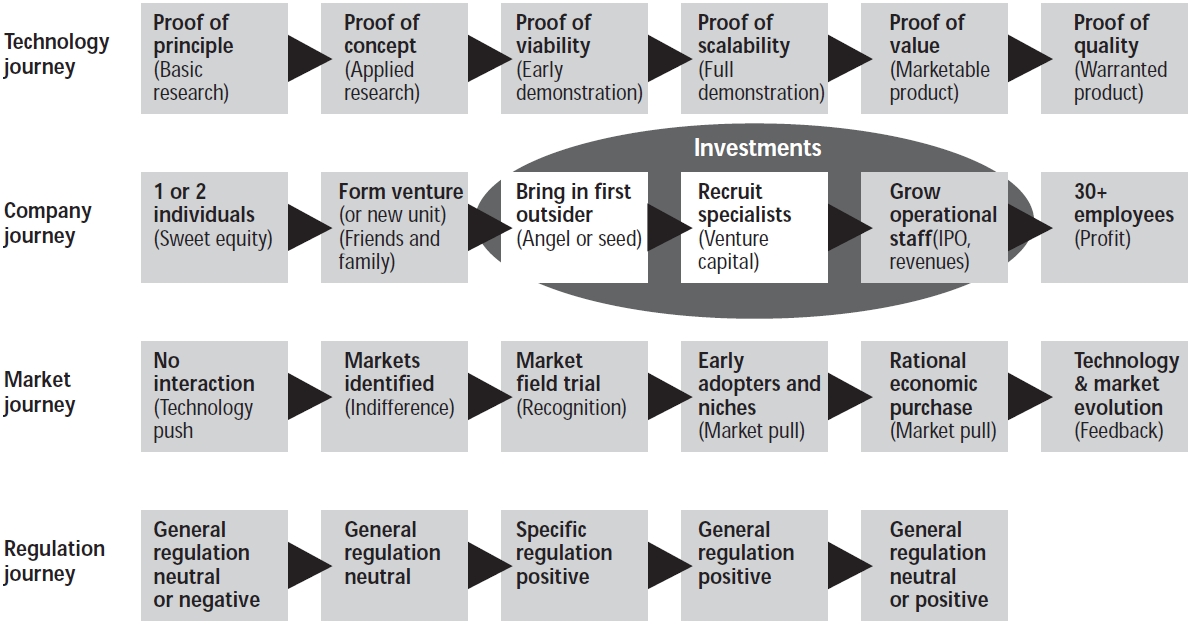

To understand how these kinds of initiatives can be deployed it is of value to review how the processes of pre and full incubation, technology acceleration, investment, growing enterprises and regulatory frameworks overlay technology, market and company journeys operate.

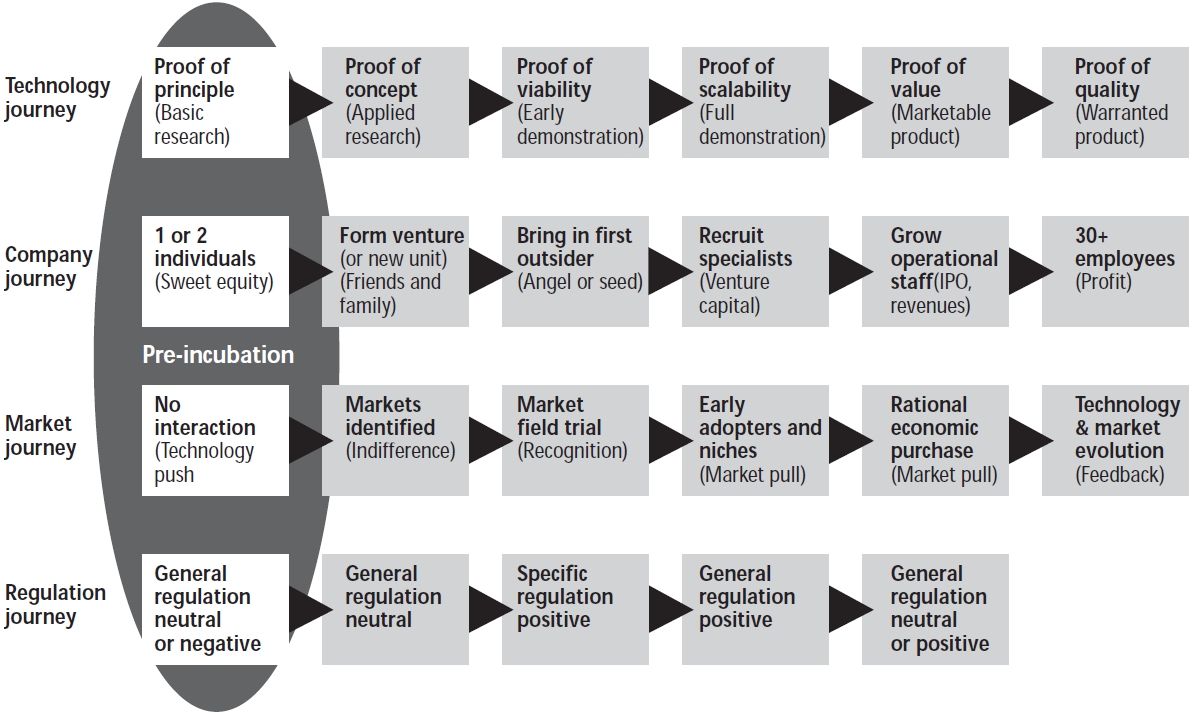

Distinctive elements that overlay these combined journeys are R&D, pre-incubation and incubation.

The science park model adopted in Europe and US does have the capacity to support R&D and some companies on these sites operate corporate development laboratories. However, the majority of the work undertaken on these sites occurs further up the value chain than the discovery stage.

In the last 5 years it has become more common for science and technology parks to create and run pre-incubators.

Pre incubation is an activity that has evolved on science parks as a development that is aimed at reducing the risk to entrepreneurs as they try to find ways of commercialising the output from research and development.

This allows entrepreneurs to gain access to low cost accommodation and free business support to help them with the investigating and defining how they intend to develop their company and embed this story in a fundable business plan. The process encourages entrepreneurs to provide clarity for investors through an executive summary, a short description of the business opportunity being pursued, a marketing and sales strategy, the proposed management

team, the operational aspects of the business, and finance.

This process is designed to support entrepreneurs as they work through the process of developing the foundations to the technology, company, and market journeys for their ideas. In most instances the process is subsidised, but time limited, and company development is measured against milestones which are agreed with the support teams in the pre-incubator.

One purpose of developing a credible business plan is to raise finance for the incubation process. In some countries the source of this initial investment is made available through government financing programmes; however, others do not offer this benefit and companies have to look to the private sector to raise finance. The features that investors are looking to understand from these documents prior to investing include understanding the technology or service being commercialised, the business that will sustain this process, the quality of the team involved in the process, and an exit route. The normal components of plans include the following elements: executive summary, company description, product or service and customer benefits, a market analysis and how this is accessed, strategy and implementation, the management team and a financial plan.

If these stages are negotiated successfully the project can then be accelerated by paying particular attention to the development of the market, building the team as the company moves to provide warrantable products that begin to secure market share.

Particular new developments that have been added to the blend of services to support these journeys include:

Employing an “entrepreneur in residence” in business pre and full incubators.

Establishing an investment group, such as an “Angel Club,” and trying to increase the capacity and skills base in this by putting in place links with international Angel and VCs.

Putting in place pre incubators through outreach programmes in other local institutions which may have individual entrepreneurs or groups of entrepreneurs that are interested in building a business.

Working with students on entrepreneurship programmes in the host university’ s business school.

Once an enterprise has reached the phase of a warrantable product on the market it is normal to move them into alternative larger but less well serviced accommodation. There is benefit from keeping these companies on the Park as they provide valuable income, they continue to develop and through this employ and train people which can help to add to the capacity of the skills base in a region, and they can attract valuable foreign direct investment if they develop as a sustainable business and are eventually acquired by another company.

There are a number of potential sources of finance to meet the needs of a growing business. Common sources include: existing shareholders and directors funds, family and friends; business angels; clearing banks in the form of overdrafts, short or medium term loans, merchant banks for medium to longer term loans, and venture capital.

It is important when choosing the source of new business finance to strike a balance between equity and debt to ensure the funding structure suits the business and assess several alternatives and based on these negotiate terms which are acceptable to the finance provider.

Common points in negotiations include whether equity the investors take a seat on the board, their voting rights, the level of warranties and indemnities provided by the directors, financier’ s fees and costs and the who carries the financial liability of funding due diligence.

Significant effort has been directed at establishing business incubation programmes which enable companies to work through these three journeys. However, an area of work that has potential for science and technology parks is to develop business acceleration activities. These accelera-

tors utilise formal training for entrepreneurs as part of the process of building a business. An example in the UK is the “New Me” programme that has been developed by The Centre for Micro Business which is based in the UK and offers a business led programme that can be added to a business incubation programme1.

Most of the businesses accelerators that offer business development support by taking equity compared with the traditional rent seeking model of pre and full incubation. These systems normally have five features. These include an application process, they are open to all businesses but compete to be adopted and those that are receive seed funding in exchange for equity, investors normally look for a team in which to invest rather than an individual, support is time limited, and the companies that are accepted pass through the investment programme as cohorts rather than as companies. These programmes normally takes between 3 and 6 months. In essence these are more focussed on enterprises that have begun to penetrate markets, have a compelling business case but need additional investment in their skills base and the finances of the company.

One of the important features of science parks is the ability to support companies above and beyond incubation by providing the space and resources to support them as they continue grow. To achieve this there is a greater emphasis on the quality and flexibly of business accommodation, the need for good access to the skills and technology and support for continuing to connect to a customer base.

This capacity to accommodate growth is an important role for science parks as they help companies to emerge from their early technology, market and company journeys.

Critical to the success of businesses in this process is finding markets and in these winning customers. One of the problems for micro companies (1 to 9 employees) and small companies (10 to 50) is finding potential customers and influencing these to the point of converting them into true customers. To support this process a number of regional strategies have been developed that have proved to be a successful formula.

The concept of an outreach programme has been pioneered on the Surrey Research Park which is based on a team of sector specific business mentors that have been set targets for working with 80 micro-companies, 35 small companies with a turnover of between ?10m and ?100m, 10 businesses with a turnover of between ?100m and ?500m, and 5 businesses that have a turnover of in excess of ?500m. The purpose of this process is to link larger companies to relevant small businesses in order to help them develop channels for acquiring technology that has potential in their market place.

In addition a number of large companies are now setting up open innovation teams that act as technology scouts that take an active role to secure new ideas for the future. A further group of companies, which can be described as technology brokers or investors that licence technology, of which one example is ANGLE Technology that was founded in 1994 on the Surrey Research Park. The company has developed a focus on the commercialisation of technology by taking a license on this and driving it up the value chain itself or by creating, developing and advising technology businesses on behalf of government and other clients.

It is clear from the experience of dealing with the commercialisation of technology that entry points of investors differs across industrial sectors and from investment group to investment group. Business Angels and other private investors can be persuaded to invest at an early stage (technology readiness levels 3 or 4) (NASA 2010), because they are connected to markets in the relevant industrial sectors. In contrast large multinationals that have open innovation programmes have a preference for technologies that are above technology readiness level 6 and have proven defendable provenance to their IP and this can be can be brought into play with relative speed.

An important role for science and technology parks is to continue to develop ways of supporting market connections for the companies they incubate.

1 info@thecentreformicrobuiness.co.uk

Science and technology parks, although not perfect instruments for facilitating economic development associated with the commercialisation of science and technology, are form of development that has been instrumental in helping to shape the technology commercialisation environment. The first science and technology parks were ad hoc developments on which it was hoped technology commercialisation could be encouraged through simple co-location of businesses and a host organisation. Experience showed that this was possible but slow and subsequently these sites evolved from being passive property developments to active sites that provide business support in the form of pre and full incubation, providing grow on space and having “on site” management with the express purpose of supporting technology transfer. The need to accelerate the rate of innovation has led to a number of innovation systems being established in which science and technology parks are an important component. These provide a policy mix that is focussed on creating the right environment to support the development of new technology based businesses and through these drive economic development.

The systems that science and technology parks have pioneered to do this include both pre and full business incubation; however, in addition some new private investors have begun to offer pre and full incubation in exchange for equity in what are now known as business accelerators. The development of these incubation systems has led to increasing interest in how to help the process of creating and building sustainable companies.

Experience shows that development of individual companies always follows a unique pathway but understanding the broad principles that underlie this process and pathway has led to the development of three distinct but interconnected pathways. These are so called technology, company and market journeys. Reviewing these journeys helps to reveal where companies can be strengthened through further investment to help them become financially sustainable businesses.