Kappaphycus alvarezii is a tropical red alga and is the principal source of the commercial hydrocolloid κ-carrageenan. The annual global harvest of Kappaphycus is 160,000 dry tons (Bixler and Porse 2010), and the entire production is obtained through cultivation. K.alvarezii (Doty) Doty ex. P. Silva and K. striatum (Schmitz)Doty from the Phillipines have been introduced into 20 countries for mariculture purposes (Thirumaran and Anantharaman 2009). Cultivation in India today has emanated from just a few K. alvarezii fragments (previously referred to as K. striatum) procured by the Central Salt and Marine Chemicals Research Institute (CSMCRI) from Japan in 1984 after following necessary quarantine and introduction procedures for experimental research and cultivation (Mairh et al. 1998). The strain is of Philippines origin. The propagules of the mother plant were germinated under laboratory conditions and introduced into the sea at the Mandapam coast, Tamil Nadu (Eswaran et al. 2002, Reddy et al. 2005), employing perforated polythene bags to insure containment, as required by Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) guidelines. Since 2000, the alga has been commercially farmed by several self-help groups along the Mandapam coast, following transfer of the technology by CSMCRI.

Although K. alvarezii has been introduced into many countries, its invasive tendency has been reported only at Kaneohe Bay, Hawaii (Conklin and Smith 2005, Goreau et al. 2008). Because CSMCRI is the technology provider, we conducted the first rapid environmental impact assessment study 2 years after initiating large scale cultivation to evaluate the environmental impact of Kappaphycus (then Eucheuma sp.) cultivation on the Mandapam coast in 2002 (Anonymous 2003). That study did not reveal any environmental concerns for K. alvarezii cultivation, except rare incidences of growth on calcareous stones in one location. Subsequently, Pereira and Verlecar (2005) reported Kappaphycus beds in sub-tidal waters without compelling evidence and expressed apprehension as to its possible spread in the Gulf of Mannar. Later, a rejoinder from CSMCRI was published for the same report (Tewari et al. 2006).

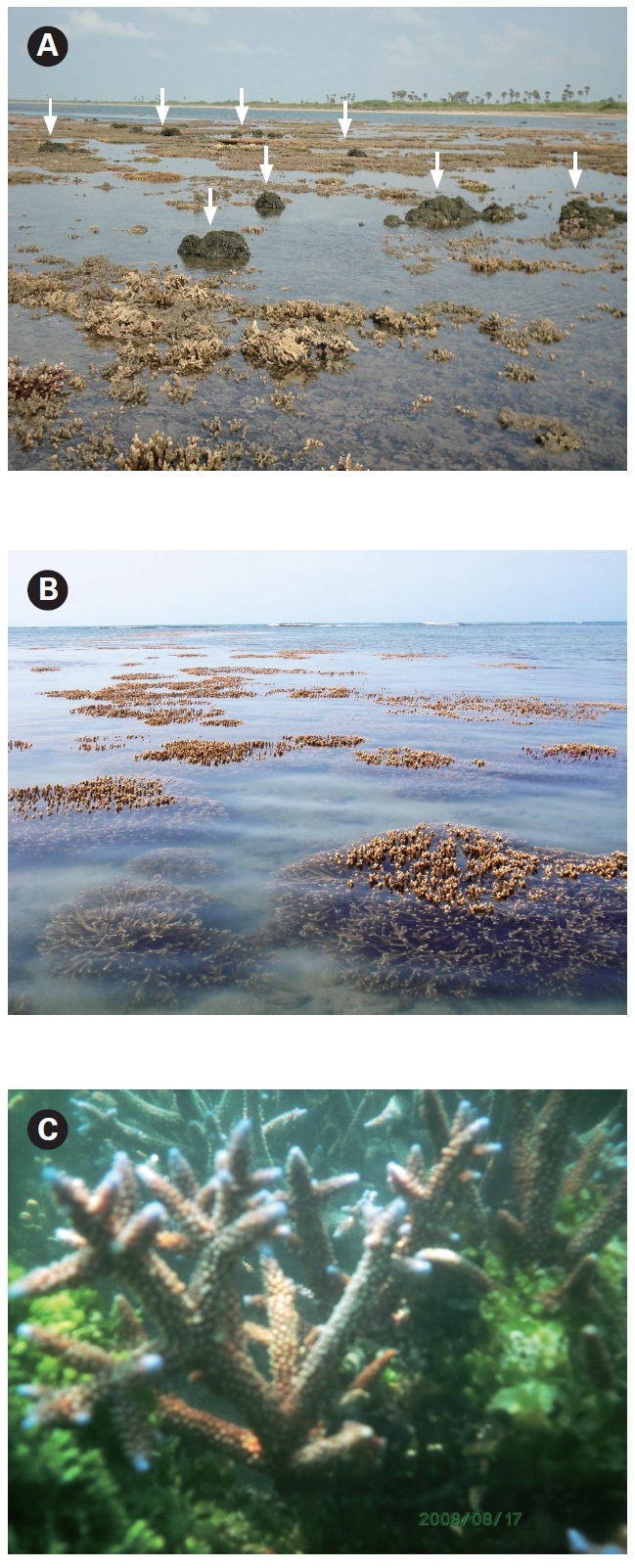

Recently, Chandrasekaran et al. (2008) reported the invasion of K. alvarezii on the Acrapora corals of Kurusadai Island. Subsequent reports also expressed concerns about endangering these native corals by the spread of K. alvarezii to other localities through sexual reproduction (Anonymous 2008, Bagla 2008). In view of this reported invasion, an extensive survey was conducted during May-August 2008 and July 2009 to gather evidence and examine the invasion potential of K. alvarezii on Acropora sp. at Kurusadai Island and two adjacent islands in the Gulf of Mannar and the mainland coast along the Palk Bay side.

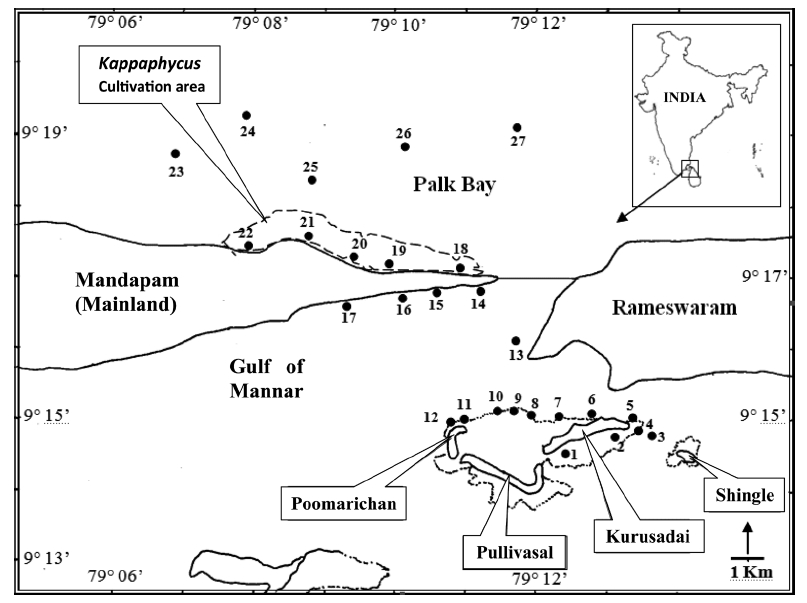

Kurusadai Island (9°14.600′ N, 79°12.000′ E-9°15.000′ N, 79°13.200′ E) is about 3 km from the mainland. A continuous fringing reef is present on the southern side of the island at a distance of 500 m. The northern and eastern sides have several patches of Acropora sp. The other two islands are Pullivasal Island (9°14.400′ N, 79°10.800′ E-9°14.400′ N, 79°12.200′ E) and Poomarichan Island (9°14.400′ N, 79°10.800′ E-9°15.000′ N, 79°11.000′ E). In the area surrounding Pullivasal Island, fringing reefs occur on the southern side at a distance of 200 m from land. Similar patchy reef distribution is also found in the muddy area on the northern side. Poomarichan Island is surrounded by a marshy area with broken coral stone and has a scanty foreshore. Extensive coral is found on the western and eastern sides of the island at a distance of 150 m from the island shore. A continuous reef exists close to the shore on the southern side.

A systematic field survey was conducted at Kurusadai Island, the adjoining Pullivasal and Poomarichan Islands, Palk Bay cultivation site, and also on the Gulf of Mannar side to determine the present status of the K. alvarezii invasion.

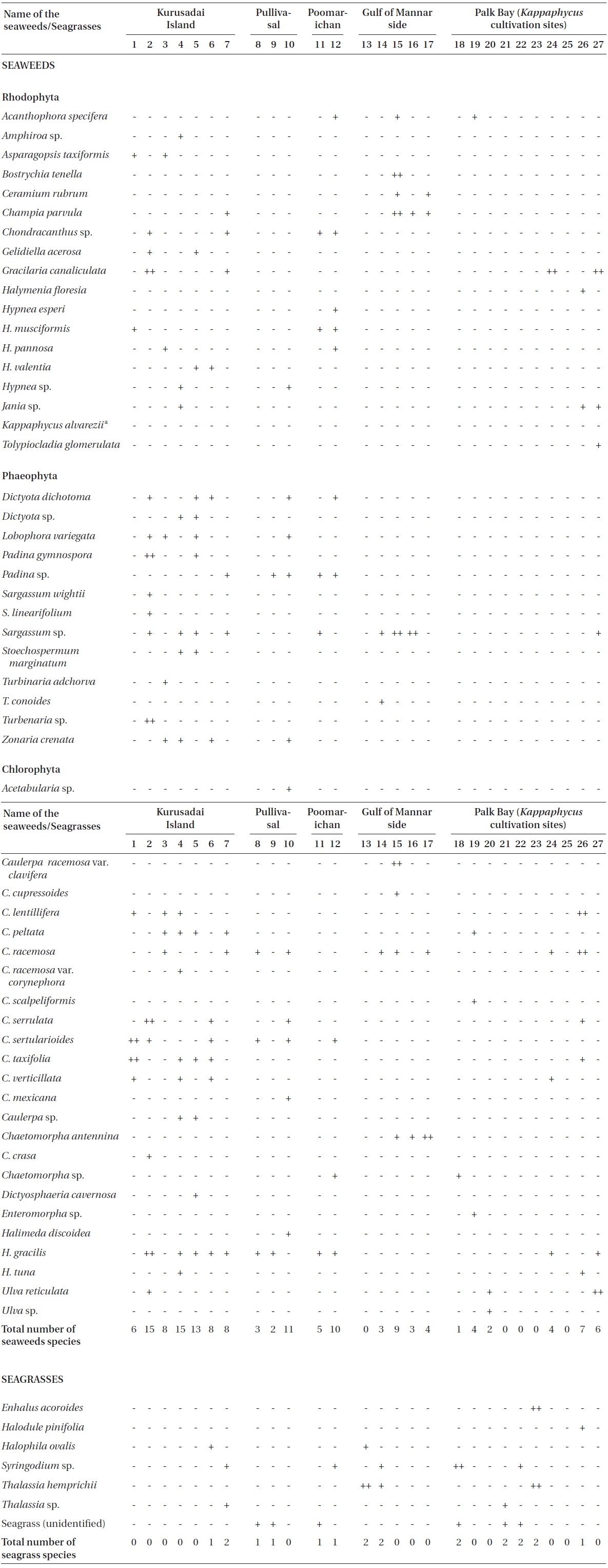

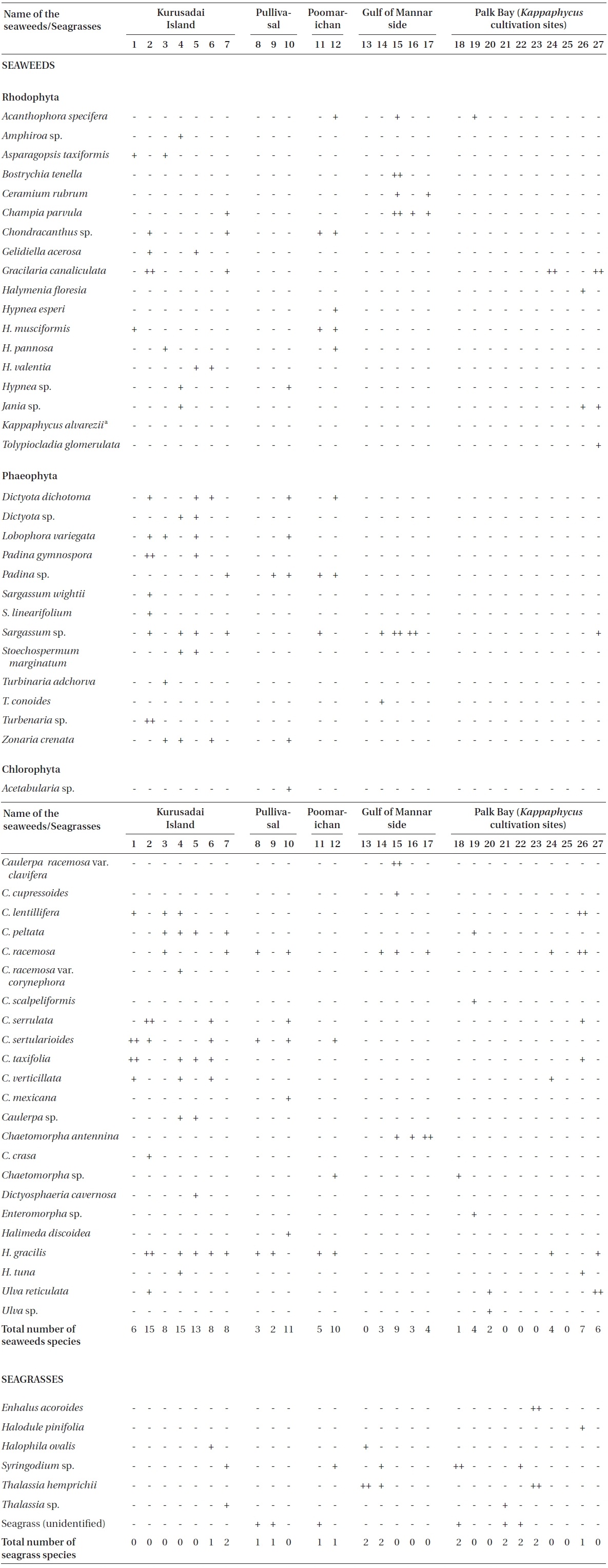

Twenty-seven unbiased sampling locations were randomly selected in the area of Kurusadai Island, Pullivasal Island, Poomarichan Island, and the mainland coast of both the Palk Bay side and the Gulf of Mannar side (Fig. 1). Global positioning system (GPS) coordinates were recorded for each sampling locality using a Garmin GPS 72 (Garmin, Taipei, Taiwan). A presence (+) / absence (-) type of survey was conducted at each sampling location to determine the K. alvarezii wild populations. Species were identified using taxonomic keys found in the literature (Ramamurthy et al. 1999, Oza and Zaidi 2001, Umamaheswara 2006). The seaweeds and seagrasses were classified based on their abundance as wild stocks either as dominant (++) or occasional (+). The spatial distributions of the seaweeds and seagrasses are depicted in Table 1. However, the biomass data were recorded only for those sampling locations where the total fresh weight was more than 500 g m-2. The species similarity index (S) was calculated using the following formula (ICMAM 1998): S = [2C/(a+b)] × 100, where C = number of species common at both two stations, a = number of species at one station, and b = number of species at the other station.

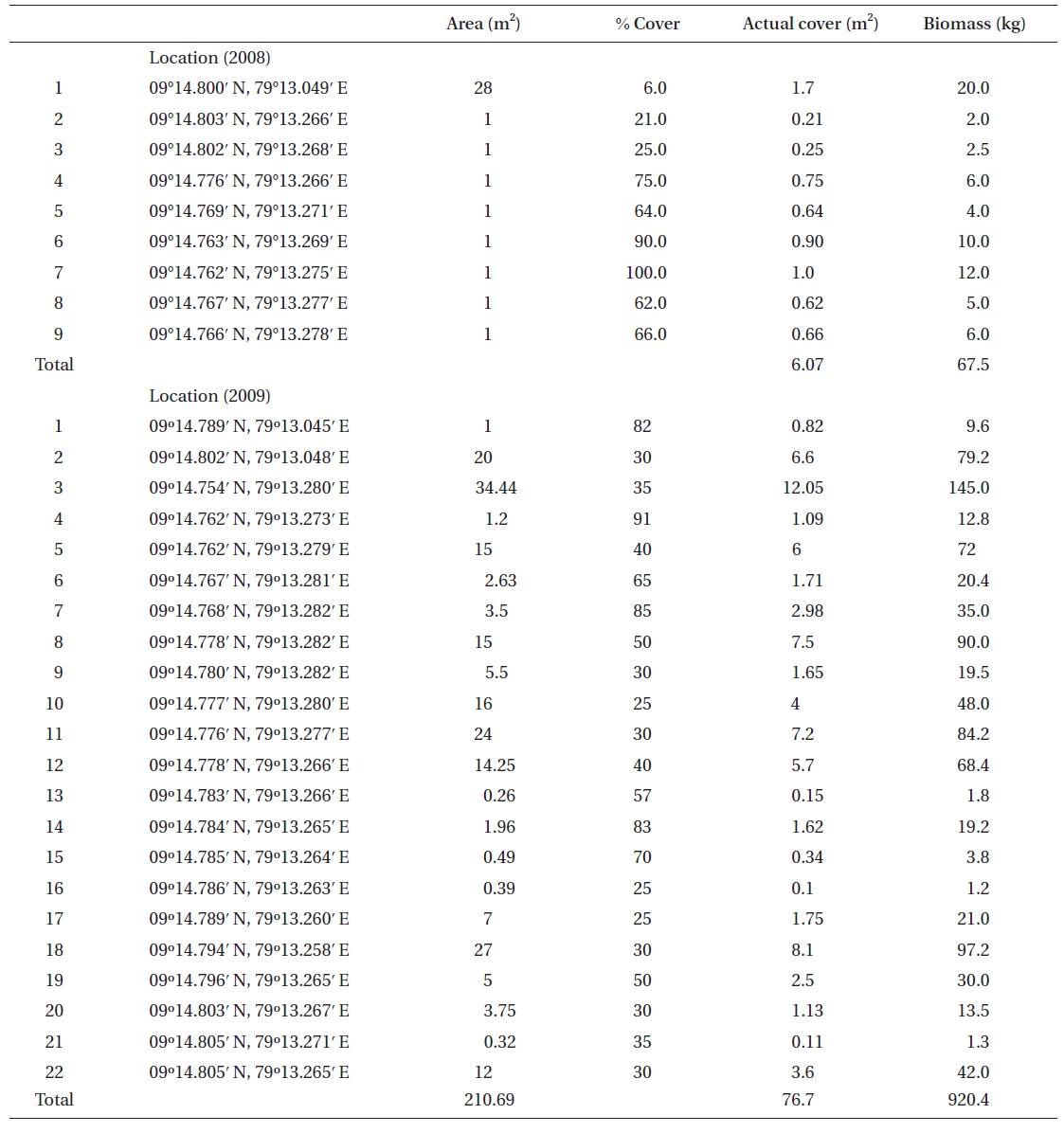

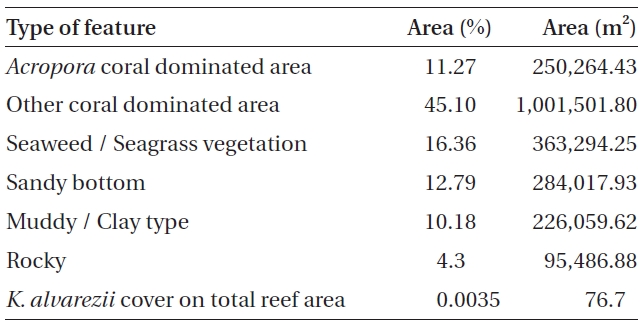

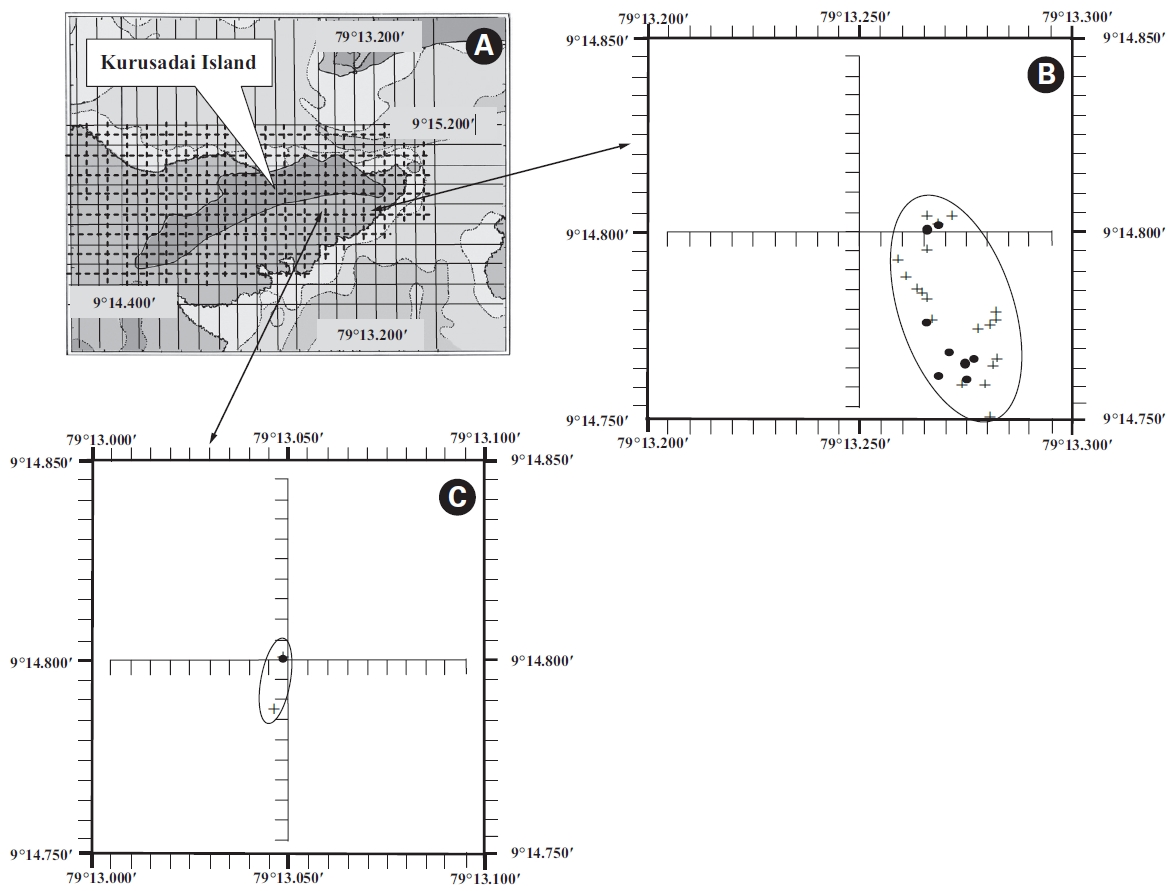

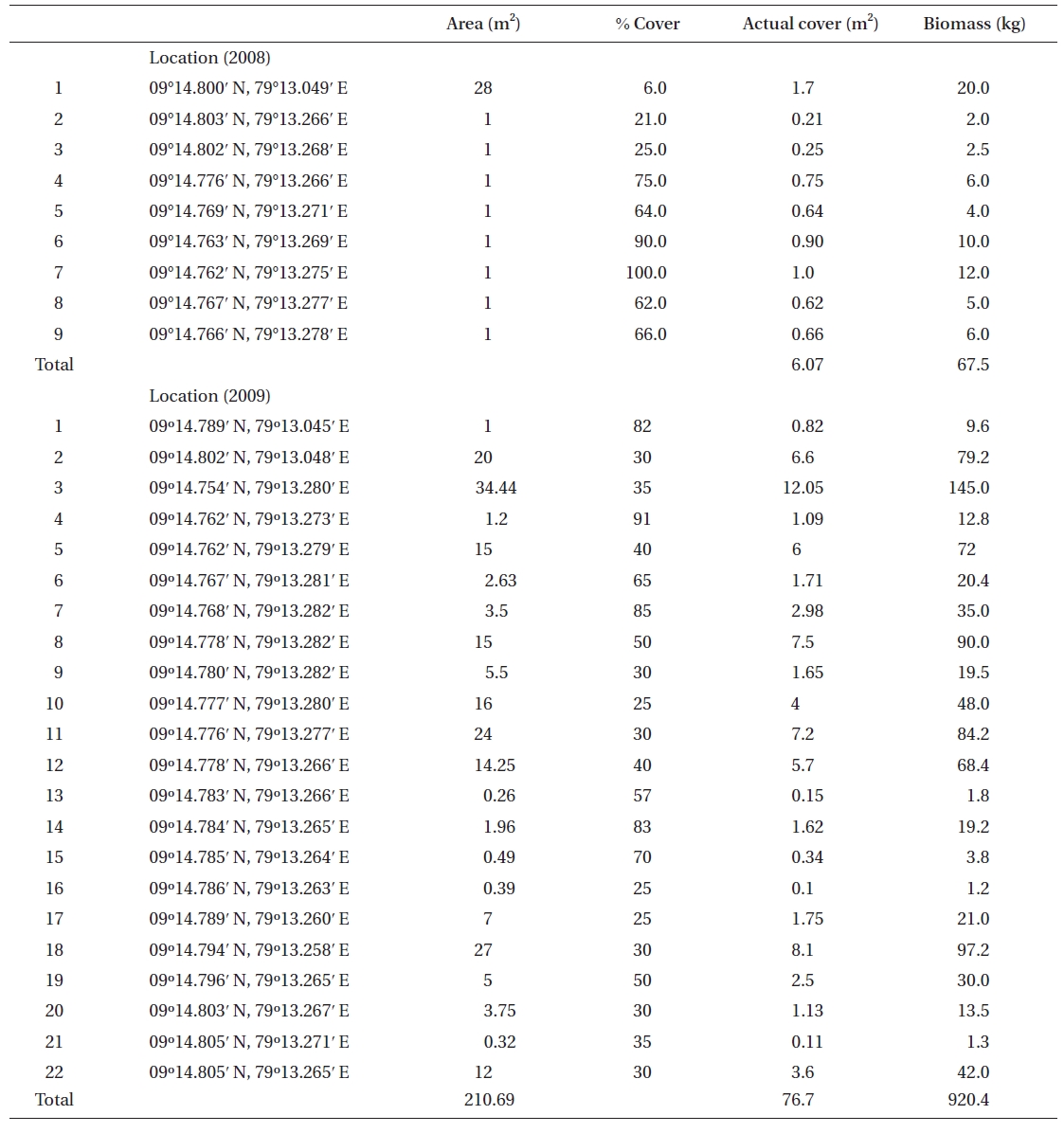

A detailed grid sampling was conducted, as we did not find any evidence of K. alvarezii at Kurusadai Island and the adjacent areas by random sampling. The entire intertidal and sub-tidal reef of about 2 km2 was divided into 275 equally sized sub-sampling grids (each 85 m × 95 m) using a hydrographical chart. A ground truth was conducted by physical verification to identify the presence of K. alvarezii (Fig. 2). The habitat characteristics (coral, seaweed, seagrass, and sand, etc.) were also recorded separately during the field study. The exact geographical coordinates were recorded with a Garmin GPS 72 wherever K. alvarezii was encountered, and its abundance on corals was estimated with the help of 1 m2 quadrates, as described by Conklin and Smith (2005).

The daily growth rate (DGR) of this alga in the abandoned conditions was calculated using the following formula: DGR (%) = [(wt/w0)1/t -1] × 100, where wt = biomass obtained during the final observation, wo = biomass obtained during the initial observation, and t = incubation time. The coral species from the study area were identified using the taxonomic keys provided by Venkataraman et al. (2003). Underwater videography and photography were undertaken with the help of snorkelers and a digital video camera (Sealife Reef Master; Pioneer Research, Moorestown, NJ, USA).

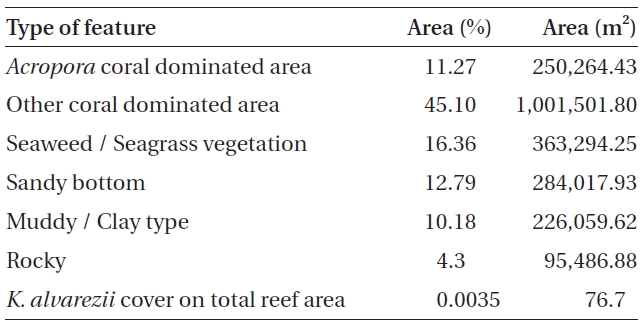

No K. alvarezii was found at any of the 27 randomly sampled locations surveyed (Table 1). In contrast, the grid sampling at Kurusadai Island revealed the presence of this alga. However, of 275 sub-sampling grids surveyed at Kurusadai Island, only three grids showed small patches of K. alvarezii on corals in the southeastern part of the island (Galaxuria point), where the corals were most abundant. The total coral area associated with K. alvarezii was estimated to be a 105 m × 55 m area in this location. Additionally, another small patch (8 m × 9 m) of K. alvarezii was also found on Acropora corals in the 2008 survey near the location where CSMCRI had maintained the germplasm of this alga until 2003 (Fig. 2). The actual extent of the K. alvarezii canopy coverage was approximately 6.07 m2 in 2008 and 76.7 m2 in 2009. However, even the latter figure amounts to only 0.0035% of the total coral reef area of the island (Table. 2 & 3). One of our co-author, Meenakshisundaram Ganesan also surveyed the reef area of Shingle island 9°14.363′ N; 79°13.935′ E - 9°14.411′ N; 79°14.169′ E (north to south direction), 9°14.540′ N; 79°13.825′ E - 9°14.609′ N; 79°13.932′ E (north to south direction) during June 2009. This reef is located on the southern side of the island and about 1 km east to Galaxaura reef of Kurusadai Island, where K. alvarezii was seen. However in Shingle Island, even a single bit of K. alvarezii was not seen in any places.

Although K. alvarezii has been cultivated on the Palk Bay side since 2000, we only found a few small fragments scattered on the seafloor. The majority of these scattered fragments were bleaching, suggesting their untenable nature. Seaweeds such as Sargassum, Turbinaria, Caulerpa, Halimeda, and Hypnea and the seagrasses Thalassia and Syrinogodium were the most common at the study area. Tolypocladia glomerulata, Gracilaria canaliculata, Caulerpa taxifolia, and Sargassum sp. were abundant along the Palk Bay side, whereas C. racemosa, C. cupressoides, Turbinaria conoides, and Acanthophora specifera were dominant species along the Gulf of Mannar side. On the Palk Bay side, seagrasses were most abundant and contributed to high biomass estimates. The maximum biomass was recorded for Halodule pinifolia with 15.4 kg (fr) wt m-2, Enhalus acoroides with 4.6 kg (fr) wt m-2, and Thalassia hemprichii with 3.6 kg (fr) wt m-2.

Kurusadai Island had diverse seaweed flora and recorded 37 different species of seaweeds. Halophila ovalis was the only seagrass recorded at Kurusadai Island. Among the seaweed species, Halimeda gracilis, C. taxifolia, Hypnea valentia, Lobophora variegate, Stoechospermum marginatum, and Gelidiella acerosa were dominant at this island. The diversity of green seaweeds was generally more than that of red and brown seaweeds at all locations studied. During this investigation, the mean total biomass of seaweeds along Palk Bay was approximately 3.04 kg (fr) wt m-2 and for the Gulf of Mannar it was less than 0.5 kg (fr) wt m-2. The S values for Kurusadai to Pullivasal and Poomarichan Islands, Kurusadai Island to Palk Bay, and Kurusadai Island to Gulf of Mannar coastal side were 0.448, 0.428, and 0.127, respectively.

The DGR of K. alvarezii on corals at Kurusadai Island was 0.7%. In most cases, seaweeds, seagrasses, dead coral rubble, or barren sand flats were entirely free of any Kappahycus. Further, the alga found on corals was in a vegetative state, and no reproductive structures were found. A screening of harvests from cultivated farms along the mainland coast also showed no reproductively active plants.

An invasive species is defined as an introduced species that is ecologically and / or economically harmful (Clout 1998). All of the invasive seaweeds reported so far have a high dispersal rate and a rapid growth rate in the recipient habitat (Critchley et al. 1987, Meinesz et al. 2001). For example, C. taxifolia spreads about 11.94 km y-1 in the Mediterranean Sea (Conklin and Smith 2005), Codium fragile subsp. tomentosoides 50-100 km y-1 on the Atlantic coast (Conklin and Smith 2005), and Kappaphycus spp. about 250 m y-1 at Hawaii (Conklin and Smith 2005). However, the Kappaphycus patches observed at Galaxuria point of Kurusadai Island did not show any lateral spreading during the years 2008 and 2009 (Fig. 2). The Kappaphycus sp. cover on the southcentral and northern part of Kaneohe Bay varied from 2% (at the southern part) to approximately 20% (at the central part). Chandrasekaran et al. (2008) reported that the K. alvarezii cover on corals varied from 5.64% at site 1 (50 m from the shore) to 34.8% at site 2 (100 m from the shore), which accounts for about 20% of the reef area, but they failed to provide the exact geographical coordinates where the alga was observed. It is evident from our study that the occurrence of Kappaphycus on corals was confined to less than 0.0035% of the total coral reef area at Kurusadai Island (Table 3). It was also noted that the corals associated with Kappaphycus were healthy and in the process of spawning, i.e., their behavior was similar to that of unaffected coral communities, belying the negative impacts reported by Chandrasekaran et al. (2008). A detailed microbiological study also showed that the coral ecosystem of this island is relatively free from known pathogenic bacteria (Haldar et al. in press), and their spawning condition indicated vigor, skeletal integrity, rigidity and health (Fig. 3C). Further, Boudouresque and Verlaque (2002) stated that an invasive species may act as a new keystone species within the recipient ecosystem. The absence of Kappaphycus in other habitats at Kurusadai Island clearly dispels the views reported by Chandrasekaran et al. (2008) that “No part of the coral reefs was visible in most of invaded sites, where K. alvarezii had doomed the entire colonies and occupied almost all ridges and valleys of the coral landscape” (Fig. 3A & B).

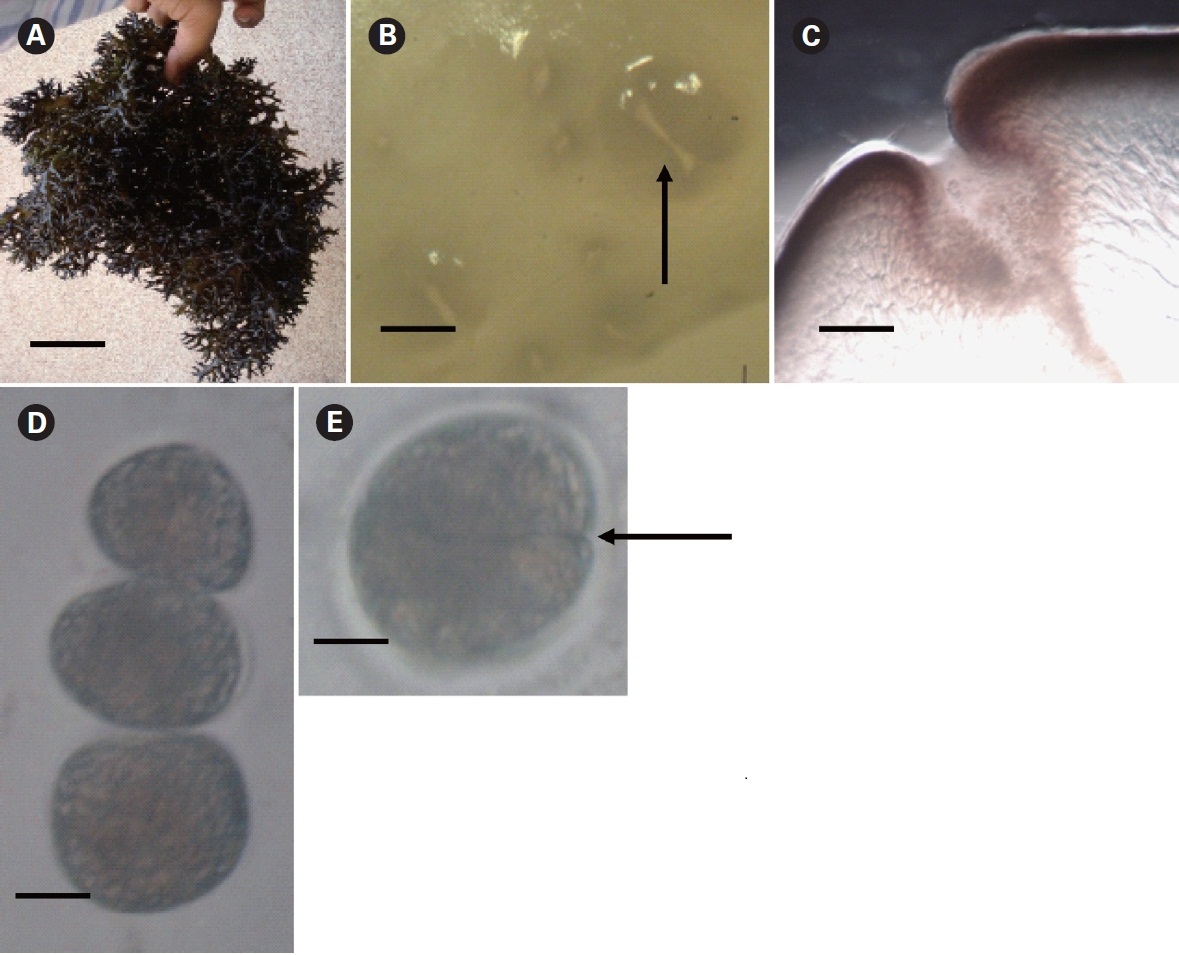

K. alvarezii propagated slowly and only vegetatively at the Kurusadai Island area; the growth rate is apparently limited by herbivores (Ganesan et al. 2006). The DGR of the K. alvarezii in a wild condition at Kurusadai Island was 0.7%, which is far less than the cultivated condition i.e., 5.69 ± 0.05% to 6.11 ± 0.04% recorded in the Vellar estuary, Tamil Nadu (Thirumaran and Anantharaman 2009). It was also observed by Eswaran et al. that DGR decreases with plant age. For example, they found that when the biomass continued to increase, the DGR declined from 8.0 to 0.4% in Palk Bay (Eswaran et al. 2006). The development of Kappaphycus reproductive structures under natural conditions is rare compared to other red algae (Doty and Santos 1978, Azanza-Corrales et al. 1992). Azanza and Aliaza (1999) concluded that no single environmental parameter alone triggers spore shedding in K. alvarezii after extensive laboratory studies performed over 40 days. Chandrasekaran et al. (2008) reported that fertile branches of K. alvarezii produce 279,000 spores g-1 thallus wet weight. These statistics were derived from extrapolated data obtained from short-term laboratory experiments (Azanza and Aliaza 1999), which may not be realistic under natural, dynamic conditions. Azanza and Aliaza (1999) reported that although the carpospores germinate in culture, they remain at the 16-32-cell stage even after 40 days. Mairh and Tewari (1994) also reported the formation of sexual propagules from cortical cells in K. alvarezii; however, the propagules developed only after prolonged laboratory culture of the mother stock over a period of 1 year. Furthermore, the culture conditions were different than the Indian coast field conditions with respect to the light : dark cycle (8 L : 16 D) and seawater temperature (22°C) in which the propagules were produced. Even under ambient laboratory conditions, K. alvarezii carpospore germlings develop pale and unhealthy tetrasporophytes, which take about 10 months to mature into a developed plant (Mairh et al. 1995, Azanza and Aliaza 1999). Conditions similar to those mentioned for the laboratory experiment (Azanza and Aliaza 1999) are less likely along the Indian coast.

K. alvarezii carpospores and tetraspores typically have low viability under various environmental conditions, and they rarely develop into fully grown plants (Mairh et al. 1995, Azanza and Aliaza 1999, de Paula et al. 1999). Although Mairh et al. (1995) reported the formation of tetraspores and cystocarps in field cultivated material, the frequency of such plants was only 7.6%, and the germination rates were 51.5% and 21.9%, respectively. More recently, cystocarpic plants collected from the Saurashtra coast, Gujarat in May 2008 have re-confirmed the above findings, as all of the carpospores died within 1 week in laboratory culture (Mantri et al. in preparation) (Appendix A). Similar findings were observed by Bulboa et al. (2008) for Kappaphycus cultivated in Brazil. Their results also indicated that establishing K. alvarezii through spores in the natural tropical environment of a country such as Brazil is rather remote. Castelar et al. (2009) observed that the DGR of K. alvarezii under cultivated conditions becomes restricted when the seawater transparency, as measured by Secchi disk, decreases to 1.6 m or less. The growth becomes negative when the transparency decreases to a depth of 0.8 m. Moreover, the growth rate of cultivated K. alvarezii is restricted when seawater temperature reaches 22.5°C and becomes negative when it is 25°C or higher. Seawater temperature plays a crucial role determining the sexual reproduction of the micro-thallus phase or the vegetative initiation of the macro-thallus from the micro-thallus phase (Luning 1990). The Gulf of Mannar experiences a tropical climate, and the period from January to May is marked by hot weather. The coldest weather is in December with a minimum of 25°C. The seawater transparency and temperature ranges in the Kurusadai Island area vary from 0.8 to 1.2 m and 25 to 36°C, respectively (Patterson 2005). Castelar et al. (2009) also reported that rapid growth of Kappaphycus requires high wind speed, i.e., more than 5 m s-1, which may help extract CO2 from the air and hasten the photosynthetic rate. Also, the alga is close to the surface during raft cultivation, whereas it mostly remains submerged condition when attached to corals, suggesting a lower phtotsynthetic rate. These observations may explain why the growth rate of K. alvarezii, established in the wild at Kurusadai Island, was much less than that observed under cultivation conditions.

A new study by a team of marine scientists from the USA and Australia suggests that coral reefs are more resistant to seaweeds than previously thought. Their study is the first global-scale analysis of thousands of individual reef surveys. In total, more than 3,500 surveys of approximately 1,800 reefs were performed between 1996 and 2006 (Bruno et al. 2009). The affected Acropora corals in the Kurusadai Island were also found spawning naturally (Fig. 3). In another recent study, Castelar et al. (2009) evaluated the invasive potential of K. alvarezii in tropical regions, such as Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and concluded that cultivating K. alvarezii is environmentally safe and secure in a tropical region. Based on a conceptual model proposed by Colautti and MacIsaac (2004), it was concluded that the determinants viz. propagule pressure, physiochemical requirements of the species, and community interactions act on exotic species to make them invasive. Therefore, it appears that the establishment of K. alvarezii at Kurusadai Island is restricted at stage three (localized and numerically rare), as all the determinants, viz. (i) seawater temperature, (ii) turbidity or seawater transparency, and (iii) propagule pressure (due to high grazing pressure) are acting negatively. The observed occurrence of K. alvarezii on corals at Kurusadai Island could merely be accidental and its confinement over a relatively small area might be due to a combination of factors, particularly those mentioned above. However, the use of hyper spectral satellite images with high spatial resolution may help in more detailed investigations of the future behavior of this alga in relation to its lateral spread into Kurusadai and adjacent islands.