Recetly, the researchers have reported that global CO2 emissions from fossil fuels increased 29% between 2000 and 2008 and 41% from 1990~2008, and the current concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere is now at its highest in at least 2 million years, according to a new study in the journal Nature Geoscience [1]. Thus, reducing CO2 emissions as a global environmental problem has been paid more and more attention.

Current or proposed methods of CO2 capture from flue gas include absorption, adsorption, cryogenic distillation, and membrane separation. However, commercial CO2 capture technology that exists today is very expensive and energy intensive. Improved technologies for CO2 adsorption are necessary to achieve low energy penalties [2]. The CO2 adsorption is typically used at a final polishing step in a hybrid CO2 capture system [3]. Up to now, different types of adsorbents have been used in CO2 capture, such as zeolites,alumina, mesoporous silica, CaO, porous carbons [4-8].Especially, porous carbons were used in CO2 separation due to their highly developed porosity, an extended surface area,surface chemistry, and thermal stability. Previous studies toward the use of activated carbons, activated carbon fibers,carbon molecular sieves, carbon nanotubes as an adsorbent for CO2 capture [9-11].

Graphite nanofibers (GNFs) as one of the most important carbon materials, which have been attracted much attention due to their novel properties such as high aspect ratio, small radius of curvature, high mechanical strength, unique electrical properties, and chemical stability [12]. Therefore,these properties that make them potentially useful in many applications as gas storage, electrodes, filler, and catalyst supports [13-16]. However, the studies of CO2 adsorption on GNFs are still very limited in the literature. This is due to that the specific surface area of GNFs is lower compared with other carbon materials. CO2 adsorption generally depends on their physical and chemical properties. Physical properties of carbons include their specific surface area, size, and porosity,whereas chemical properties are mainly determined by their surface functional groups, including carboxyl, carboxylic anhydrides and so on [17]. To date, several methods have been used in order to obtain porous GNFs, including the activation at high temperature with CO2 or a water steam stream and a chemical activation method [18-20].

In the present work, we focused on the preparation of porous and ammonized GNFs, in order to improve the CO2 adsorption capacity of GNFs. The GNFs with different physical structures were prepared by ammonia and heat treatment at temperatures up to 1000oC, and their physiochemical properties and CO2 adsorption capacity were investigated.

2.1. Materials and Sample Preparation

The GNFs (straight type, Nanomirae Co.) were activated with HNO3 for 12 h at 60oC. The 10 g of activated GNFs were dispersed in 50 ml of ammonia solution by mechanically stirring the mixture for 24 h at 60oC and then filtered and dried 24 h at 60oC. The sample was denoted as GNF-A.About 2 g of ammonized GNFs were placed in a quartz tube reactor, heated at 10oC/min to 500oC, 700oC, 900oC, and 1000oC, in N2 flow and keep for 2 h, and the obtained samples were denoted as G-A-500, G-A-700, G-A-900, and G-A-1000, respectively. This work employed carbon nanotubes (CNTs) purchased from Nano Solution Co. (CNTs with a diameter of 10~25 nm).

The pH of the sample was evaluated according to ASTM(American Society for Testing and Materials) Standard Procedure D 3838. Samples of 0.5 g were added to 20 ml of distilled water and suspensions were stirred overnight to reach equilibrium. The changes in chemical composition of the GNFs surfaces were analyzed by elements analyzer(Thermo EA1112). Then, the samples were filtered and pH of the solution was measured.

N2/77 K full isotherms were measured using an ASAP 2010 (Micromeritics). Before the measurement, the samples were degassed at 200oC for 12 h to obtain a residual pressure of less than 10-6 mm Hg. The N2 adsorbed on the GNFs was used to calculate the specific surface area by means of a BET (Brunauer-Emmett-Teller) equation. The total pore volume was estimated to be the liquid volume of the nitrogen at a relative pressure of about 0.995, and the microand mesopore structures were analyzed using D-R (Dubinin-Radushkevich) and BJH (Barrett-Joyner-Halenda) equations,respectively. Wide-angle X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the GNFs were obtained with a Rigaku Model D/MAX-III B diffraction meter equipped with a rotation anode using CuKα radiation (λ =0.15418 nm). The CO2 adsorption property of GNFs was characterized by surface area analyzer(BEL, Japan) at 273 K in this system (1 atm). Before each analysis, samples were degassed for 12 h at 200°C.

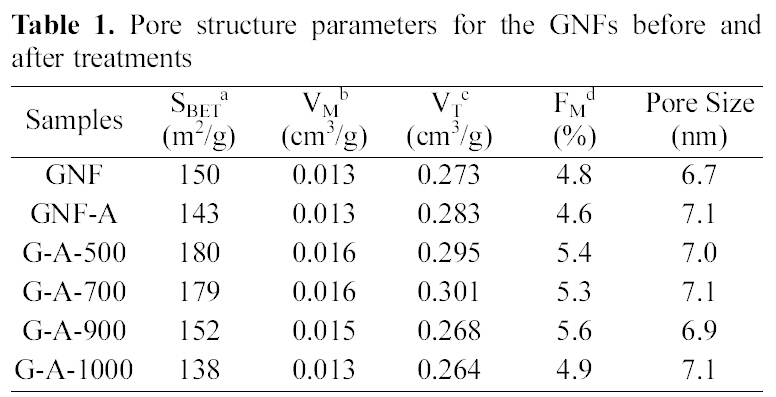

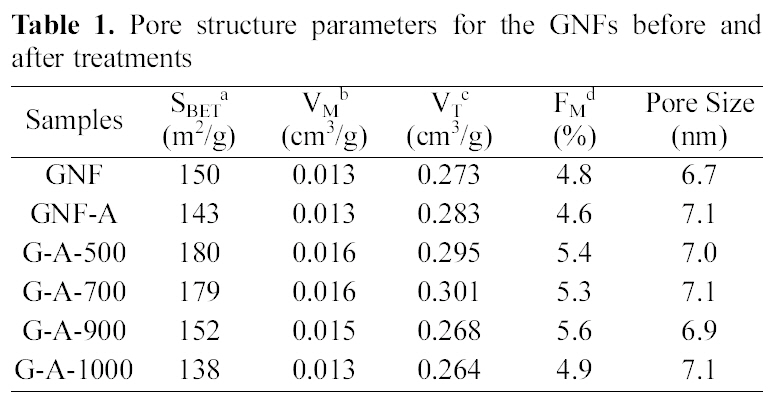

Table 1 shows the textural properties of the GNFs before and after treatments. It was observed that the pore structure of GNFs and treated GNFs does not change much due to modification by either ammonia treatment or heat treatment.The specific surface areas of GNFs decreased after treated with ammonia. The small changes in the pore structure are attributed to creation of functional groups such as lactam groups, pyrrole and pyridines [21]. It was found that the specific surface area the fractions of micropore increased to G-A-500, but then showed a decrease at G-A-1000. It can be seen that the micropores were mainly enhanced in the lower temperature, but, the mesopore volume was increased in the

[Table 1.] Pore structure parameters for the GNFs before andafter treatments

Pore structure parameters for the GNFs before andafter treatments

higher temperature. Yoon

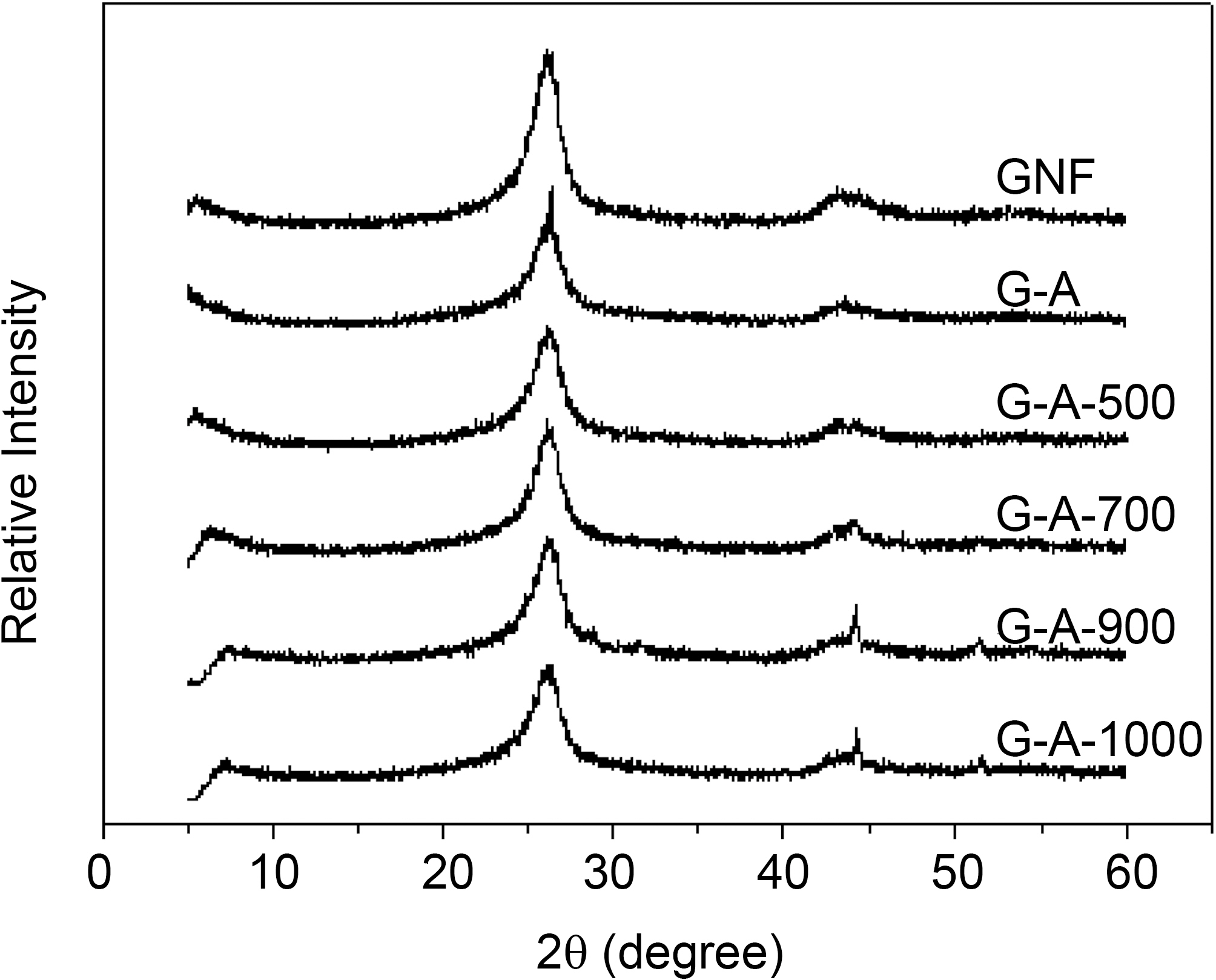

Fig. 1 shows the XRD patterns of the GNFs before and after treatmentss. It reveals that the peaks were explicable in terms of the known structure of the graphite at 2θ=26.1°(002) and 43.1° (101) peaks. It show also the presence of metal catalysts peaks at 2θ=44.3° (111) and 51.4° (200)peaks. The graphite peak (002) intensity gradually decreases with increasing temperature, probably because higher temperature affects the graphene layer structures of GNFs. In the case of G-A and G-A-500, the XRD patterns have not significantly change.

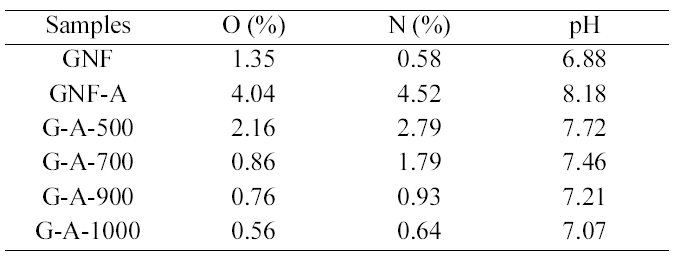

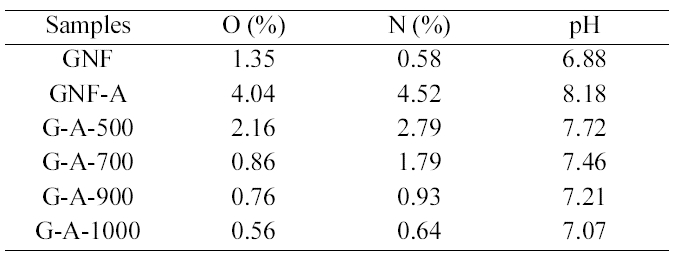

The elemental compositions as determined by elemental

[Table 2.] Elemental analysis and pH values of the GNFs before and after treatments

Elemental analysis and pH values of the GNFs before and after treatments

analysis are presented in Table 2. It appears that ammonia treatment yields a lower content of nitrogen. The nitrogen content decreases with increasing treatment temperature,reaching a maximum at 500°C and 700°C. The reaction of ammonia with carbon can be expected to take place at acidic sites, formed mainly by surface acidic functional groups as carboxylic groups [25]. This is due to that the nitrogencontaining functional groups such as lactams, imide, and amides may be formed from ammonia by mild conditions(500, 700°C) and can be desorbed at high temperature(1000°C). The acid and basic character of GNFs are assessed by the pH values and also shown in Table 2. It shows that the pH values of ammonia treated GNFs decreased with increasing treatment temperature. This means that the types of chemical nitrogen fixation by GNFs: nitrogen bound to the carbon as aside group, such as an nitrogen functional group, nitrogen chemically bound on the carbon surface as a lactam, or pyridine-pyrrole-like group and as a nitrile.

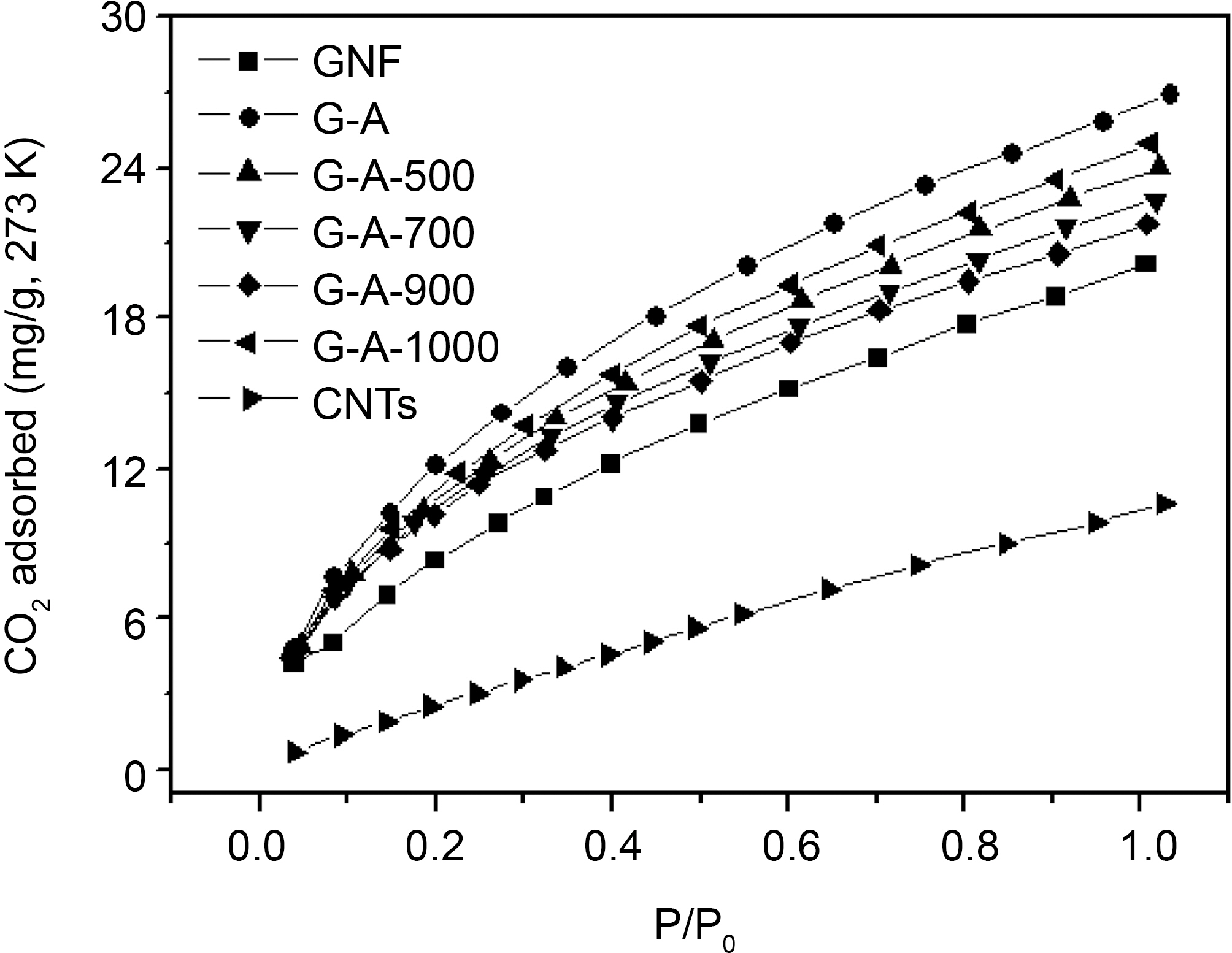

The CO2 adsorption capacities were measured by CO2 adsorption isotherms at 273 K (1 atm). The commercial CNTs with surface areas of 230 m2/g and CO2 adsorption capacities of 10.6 mg/g, and the GNFs was able to achieve 20.2 mg/g of CO2 adsorption capacities (Fig. 2). It is clear that GNFs show better performance compare with CNTs. As shown in Fig 2, the ammonia treated GNFs present better performance for CO2 adsorption than the pristine GNFs. The behavior of the ammonia treated GNFs to adsorb CO2 should be related to the number and availability of amine groups for reaction [15,16]. As described by Mangun et al. [24], the modification of activated carbon fibers (ACFs)with dry ammonia from 500 to 800°C for different periods of time leads to a formation of new nitrogen-containing groups in the fibers. The formation of carbamate is favored in the manner shown in Eqs. ((1), (2), and (3)). Two moles of amine groups react with 1 mol of CO2 molecule [26].

In addition, the gas adsorption is greatly depended on the micropores of carbon materials. Therefore, the highest CO2 adsorption capacity of 26.9 mg/g is shown for the GNFs treated with ammonia in low temperature (500°C). This result clearly indicates that ammonia and heat treatment leads to increase of the affinity of GNFs towards CO2.

In this work, the commercial GNFs with different physical structures were prepared by ammonia and heat treatment at temperatures up to 1000°C to improve its CO2 adsorption capacity. We found that the ammonia treatment introduced nitrogen-functionalities into the surface of GNFs, which resulting in increasing their CO2 adsorption capacity. In addition, the heat treatment led to an improvement of the microporosity of GNFs at lower temperature. The GNFs treated at 500°C showed highest CO2 adsorption capacity of 26.9 mg/g at 273 K in this system. We concluded that in order to obtain a high CO2 adsorption capacity, two key conditions are required: well-defined microporosity and well-developed basic functional groups of the solid surfaces studied.