Pharmaceuticals used for human and livestock are biologically active compounds. Unlike the earlier assumption that the residual concentration of pharmaceuticals in the environment would not be as high as to cause substantial harmful effects on human and ecosystem health, many recent studies raised concerns on these pharmaceutical compounds and their metabolites in the environment.1-13) In addition, researchers identified residual pharmaceuticals in environmental samples with the development of instrumental methods especially using liquid chromatography- mass-mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS). For example, German scientists identified many parent drugs and their metabolites in sewage treatment effluents as well as in receiving waters.6) Many antibiotics and prescription and nonprescription drugs were found in samples collected from 139 streams during 1999-2000 by the national reconnaissance in the United States.7) In Korea, many pharmaceuticals including acetaminophen, carbamazepine, diclofenac, ibuprophen, sulfathiazole and chlortetracycline were detected in wastewater influents and effluents8) and were found in river water.9) To cope with these raising environmental concerns, Ministry of Environment (MOE) planned a five-year extensive survey for 27 selected human and animal pharmaceuticals.14)

Although the quantity of monitoring data is rapidly increasing with the improvement of their quality as well, they are still far limited to rigorously evaluate the fate of pharmaceuticals of environmental concerns for the prediction of environmental exposure. There are many potential pathways for pharmaceuticals to enter the environment including manufacture and handling, aquaculture, agriculture, disposal of waste or wastewater contai ning them.1,15-17) Among these potential pathways, effluents from sewage treatment plants or animal waste treatment plants are considered as important point sources of pharmaceuticals and their metabolites.6,18) Removal of pharmaceuticals can be mostly achieved by biological degradation or sorption to sludge in conventional sewage or animal wastewater treatment plants using activated sludge processes.6,7,18) Thus, it is of critical importance to know the fate of pharmaceuticals in a wastewater treatment plant. Since monitoring concentrations of potential pharmaceuticals both in the influent and the effluent requires a lot of time and cost, it is wise to use a predictive model to reduce our efforts especially in the screening stage and to minimize monitoring practice.

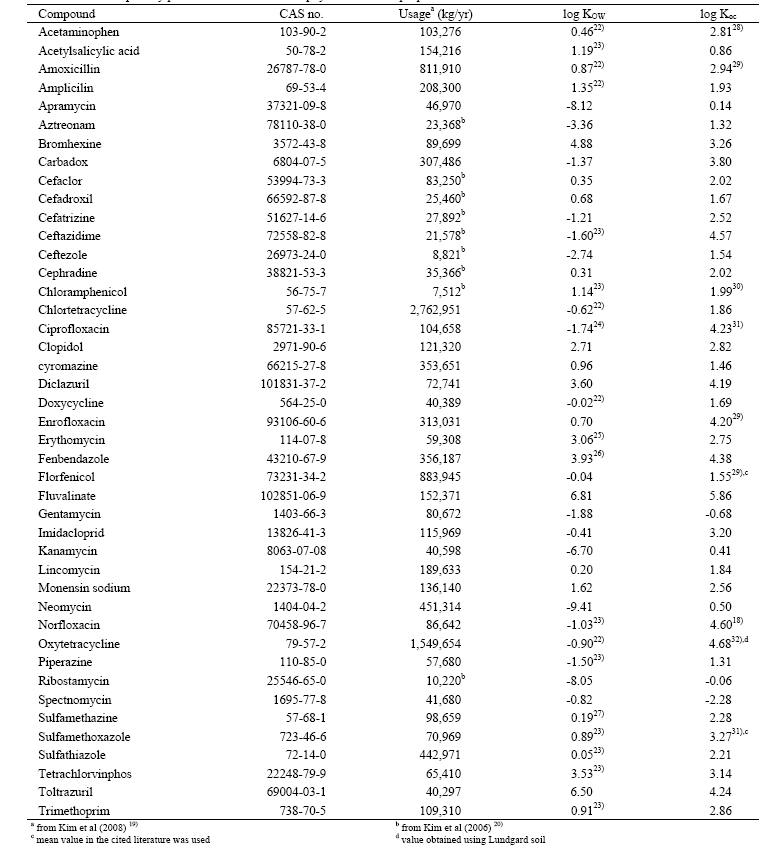

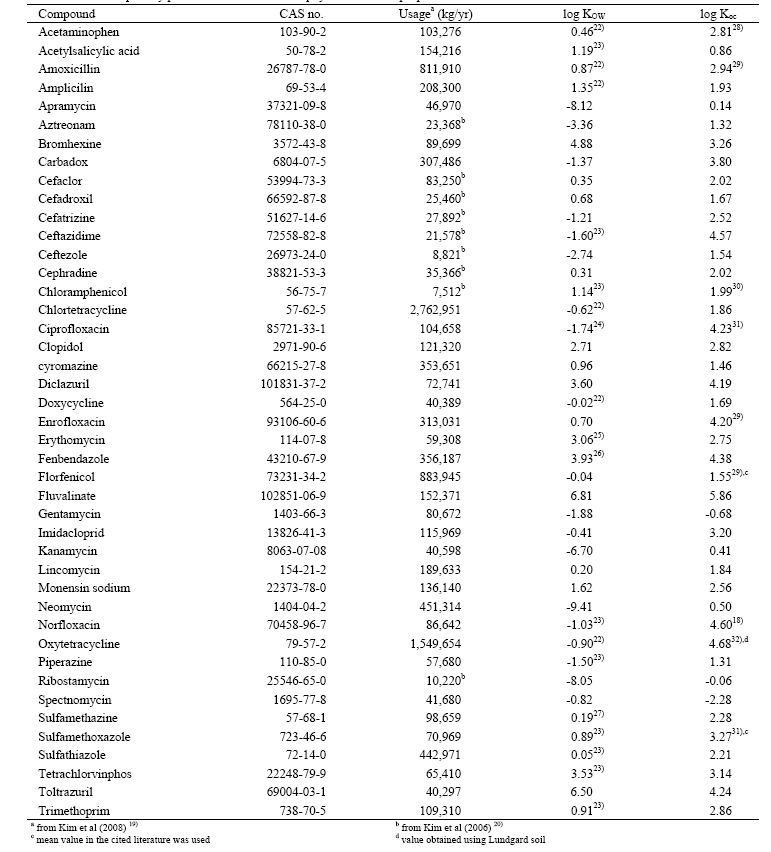

[Table 1] Selected priority pharmaceuticals with their physico-chemical properties

Selected priority pharmaceuticals with their physico-chemical properties

Consequently, we evaluated the fate of priority pharmaceuticals in Korea using two sewage treatment plant models: an equilibrium sorption model and STPWINTM program. Two critical parameters, sorption coefficients to suspended sludge and biodegradability, were selected after reviewing literature or estimated using a molecular connectivity index model and BIOWIN model. Predicted removal efficiencies were then compared based on different assumptions used. A strategy of using a sewage treatment plant model to estimate predicted exposure concentration (PEC) in aquatic risk assessment was also suggested.

2.1. Priority Pharmaceuticals in Korea

Table 1 summarizes human and veterinary pharmaceuticals selected for the evaluation of their fate in a conventional STP. They were chosen based on the evaluation of their usage, persistence, and ecotoxicity. Detailed methods were described in Kim et al.19) We chose veterinary medicines from the list classified as compounds which require further hazard assessment by Kim et al.19) Furthermore, we limited our assessment to 34 veterinary pharmaceuticals with relatively low molecular weight (< 800 g/mol) because the measurement and prediction of partition coefficients (log KOW and log Koc) are not reliable for high molecular molecular weight compounds. We also added 9 priority human antibiotics from Kim et al.20) to our evaluation list because antibiotics account for the greatest portion in Korean market and abuse of them may cause irreversible ecological effects.2,11,21)

2.2. Collection of Literature Data

As shown in Table 1, we collected data influencing the fate of pharmaceuticals in an STP. Priority of log KOW values used in this study was in the order of recommended values by Dr. James Sangster from an on-line database,22) experimental data found in various literature,18,22-32) and predicted values by KOWWIN program using a group contribution method.33) Organic carbon-water partition coefficients (log Koc) were preferred for partition coefficients between suspended sludge and water if they are available. Otherwise, we used predicted an organic carbon-water partition coefficient using molecular topology/ fragment contribution method34) for the equilibrium partitioning model (EPM) (detailed description of this model in the next section). Because all the chosen pharmaceuticals are not highly volatile (Henry’s law constant less than 10-8 atm-m3/mol), loss by evaporation was neglected in our evaluation. For STPWIN, we used the default prediction method used in the program which predicts a biomass-water partition coefficient (KBW) using log KOW by: 35)

2.3. Sewage Treatment Plant Models

2.3.1. Equilibrium Partitioning Model (EPM)

The conservative evaluation considering only sorptive removal by suspended solids may be reasonable because many pharmaceuticals are not readily biodegradable.7,36) Depending on their sorption coefficients between suspended solids and water, removal by sorption may or may not be significant. Sorption to suspended solids is dominated by organic carbon fraction (foc)37) for hydrophobic pharmaceuticals and thus organic carbon-water partition coefficients (Kocs) are significant.

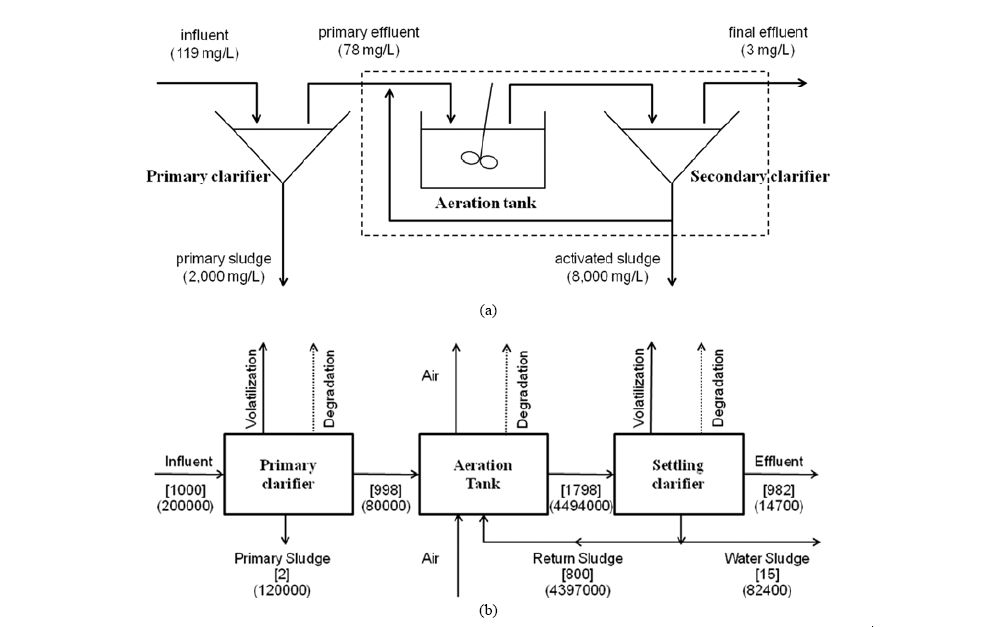

An equilibrium sorption model was used to evaluate removal efficiency in a typical sewage treatment plant (STP) composed of primary settling tank, aeration basin, and final clarifier. A schematic diagram of an STP is shown in Fig. 1(a). Total suspended solids (TSS) concentrations in the influent, the primary effluent, the primary sludge, the activated sludge, and the final effluent were assumed to be 119, 78, 2,000, 8,000, and 3 mg/L, respectively, as assumed by Heidler and Halden.18) It was further assumed that TSS contains 30% organic carbon and 90% of activated sludge is removed in the final clarifier.18) Thus, removal of a pharmaceutical can only be achieved by sorption to sludge. After algebraic calculation, the overall treatment efficiency (R) can be obtained by:

where subscripts in, pe, and as represent influent, primary effluent, and activated sludge. The units of Koc and TSS are L/kg organic carbon and mg TSS/L, respectively. Detailed derivation and a simple calculation model using Microsoft Excel ver. 2007 are available upon request to the authors.

2.3.2. STPWINTM Model

Fate of the selected pharmaceuticals were also evaluated using STPWIN program in EPISuite ver. 4.038) developed by Mackay and co-workers.35,39) It employs a fugacity approach to estimate the fate of a chemical pollutant in the wastewater influent. Primary clarifier, aeration vessel, and settling tank are three major compartments in which thermodynamic equilibrium between water and suspended solids is assumed.35) A schematic diagram of the model is described in Fig. 1b. The compound can be removed by evaporation, biodegradation, and sorption to sludge. The most critical variables in this model are the pseudo-first order biodegradation rate, biomass-water partition coefficient and the biomass concentration. Thus, a user can input half-lives of a chemical in the three major compartments or use output from BIOWIN program also included in EPISuite program. Since the ready degradability data and biodegradation rate constants are sparingly available for the selected pharmaceuticals, we used the estimated biodegradability from BIOWIN program and default classification of half- lives in the three major compartments. 33)

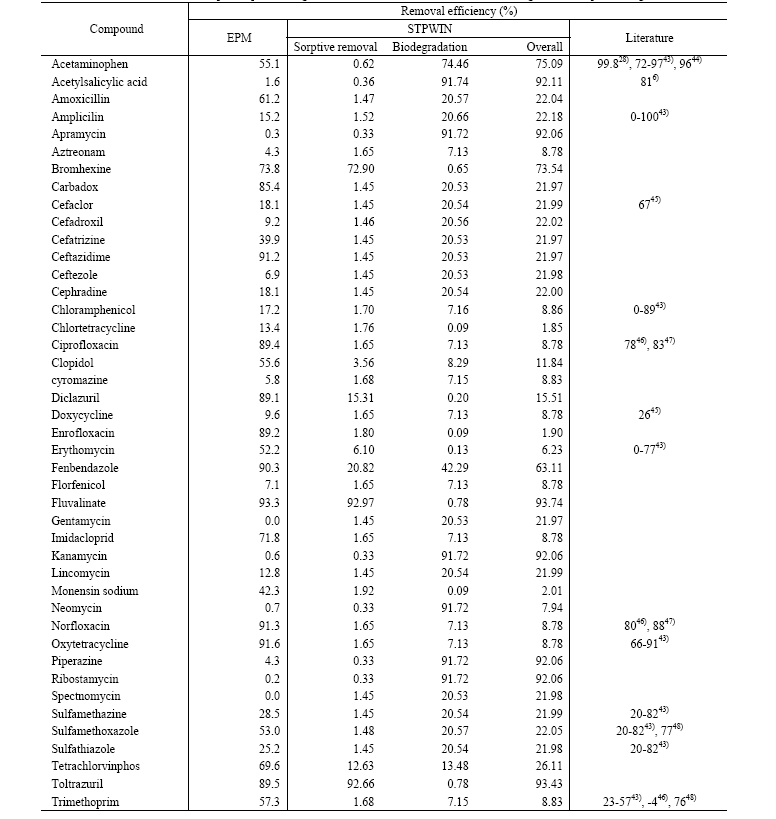

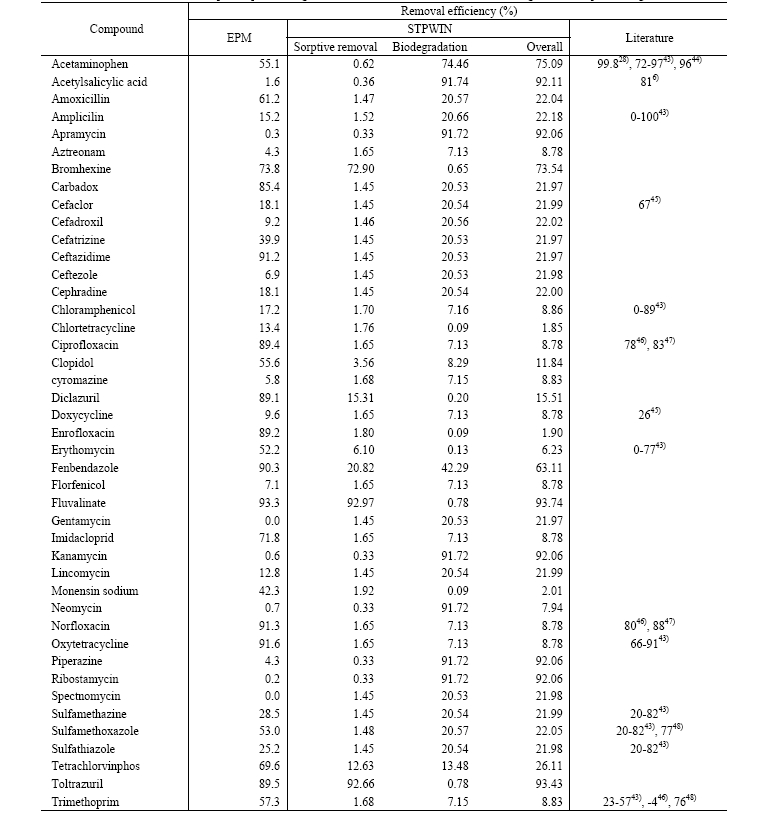

Expected removal efficiencies of the priority pharmaceuticals in an STP are shown in Table 2. According to the EPM, less than 20% removal was expected for more than half of the selected pharmaceuticals, indicating that a conventional wastewater treatment process is not likely to be efficient for protecting aquatic ecosystem receiving wastewater effluent. On the other hand, predicted removal efficiencies using STPWIN were typically higher than those using the EPM for pharmaceuticals classified as “biodegradable”. However, the sorptive removal efficiency is higher in EPM. Lower sorptive removal in STPWIN for pharmaceuticals with low log KOW (< 2.0) is originated from the prediction of biomass-water partition coefficient (KBW) using equation 1. As shown in Table 1, log Koc may be very high compared to log KOW because of polar interactions between pharmaceuticals and natural organic matters.40) For example, experimental log Koc values are 4.2331) and4.618) for ciprofloxacin and norfloxacin whereas their log KOW values are 0.28 and -1.03.

In general, low removal efficiencies were expected for pharmaceuticals having low log Koc or log KOW less than 2.0 and resistant to biodegradation such as aztreonam, chlortetracycline, cyromazine, florfenicol, and neomycin both in the EPM and STPWIN. Thus, monitoring the fate of those persistent chemicals should follow to know environmental load from an STP.

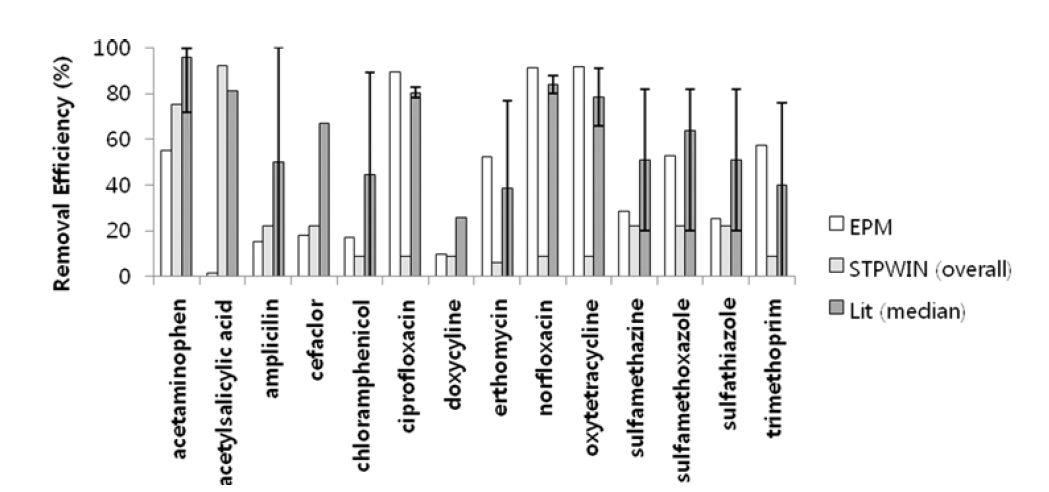

Predicted removal efficiencies obtained using EPM agreed well with literature values for ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, norfloxacin, oxytetracycline, sulfametazine, sulfamethoxazole, and trimethoprim. However, those predicted using EPM underestimates the overall removal efficiency for acetaminophen and cefaclor probably due to neglecting biological degradation in an STP. Contrary to EPM prediction, predicted removal efficiencies using STPWIN underestimate the overall removal although it incorporates biodegradation processes. As mentioned earlier, this underestimation is associated with the underestimation of KBW (eq. 1). Thus, a better prediction of KBW should help the performance of STPWIN especially those pharmaceuticals having low log KOW. Fig. 2 compares predicted removal efficiencies using the two models to literature values for the pharmaceuticals with reported removal efficiency.

3.2. Effects of Sorption to Sludge

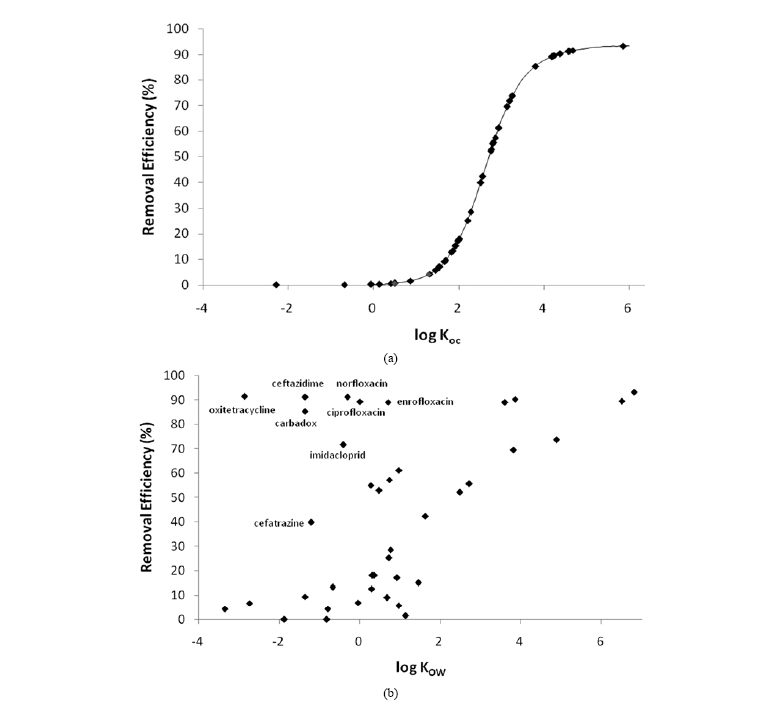

Fig. 3 shows predicted removal efficiencies of 43 priority pharmaceuticals with respect to log Koc (Fig. 1(a)) and log KOW (Fig. 1(b)). As shown in Fig. 3(a), removal efficiency by sorption dramatically increases with increasing log Koc. Although it depends on parameters such as TSS concentrations, 64% and 92% removals solely by sorption were expected for a compound with log Koc of 3.0 and 5.0 respectively under our assumptions

Fig. 3 shows predicted removal efficiencies of 43 priority pharmaceuticals with respect to log Koc (Fig. 1(a)) and log KOW (Fig. 1(b)). As shown in Fig. 3(a), removal efficiency by sorption dramatically increases with increasing log Koc. Although it depends on parameters such as TSS concentrations, 64% and 92% removals solely by sorption were expected for a compound with log Koc of 3.0 and 5.0 respectively under our assumptions

Removal efficiencies in aqueous phase using the EPM and mass balances in a model sewage treatment plant using STPWIN

(Fig. 1(a)). Since sorptive removal is determined by sludge removal, higher TSS concentrations in primary and activated sludge should result in higher removal efficiency. However, the relationship between the removal efficiency and log KOW scattered a lot. Because log Koc predicted using a molecular connectivity index, it is not linearly correlated with log KOW. For example, predicted log Koc of ceftazidime, a prescription antibiotic, is 4.57 although its log KOW was reported to be -1.60 (Table 1). Predicted log Koc values for carbadox, cefatrizine, and imidacloprid were much higher than their log KOW values,

thus they deviate significantly from the general relationship between removal efficiency and log KOW (Fig. 3(b)). For those pharmaceuticals, STPWIN predicted much lower sorptive removal because it employs a log KOW based sorption model (eq. 1). In addition, many pharmaceuticals are ionizable at ambient pH and this affects sorption as well because sorption coefficient to suspended solids depends on charge state.

Since the prediction of removal efficiencies of pharmaceutical was strongly affected by sorption coefficient to sludge, it is very important to know reliable sorption coefficients to suspended solids. In addition, traditional log KOW-based simple linear free energy relationships (e.g., equation 1) significantly differs from molecular topology methods41,42) used for the estimation of log Koc in this study. Recent studies also showed that log KOW alone is not able to reliably predict log Koc.40) Furthermore, experimentally determined sorption coefficients may not be predicted well by the molecular connectivity index methods. Among nine pharmaceuticals for which experimental log Koc values are available, predicted values using KOCWIN deviated more than one order of magnitude for acetaminophen, ciprofloxacin, enrofloxacin, norfloxacin and oxytetracycline. Thus, it is of critical importance to have experimentally determined suspended solids-water partition coefficients or to have a better model to estimate them.

3.3. Effects of Biodegradation

Fig. 4 shows the overall removal efficiency (open squares) and removal efficiency by sorption to sludge (open circles) for the selected pharmaceuticals using STPWIN. Since the evaporation loss is negligible, the difference between two series indicates the contribution of biodegradation. As shown in Table 2 and Fig. 4, biodegradation may be important in the overall mass balance of priority pharmaceuticals in an STP. Removal by biodegradation was not very high for most of priority pharmaceuticals in this study except for acetylsalicylic acid, apramycin, kanamycin, neomycin, piperazine, and ribostamycin. Many pharmaceuticals were classified as “moderate-to-slow biodegradation” or “slow biodegradation” in BIOWIN program, resulting in approximately 20% and 7% removals by biodegradation, respectively. This indicates that both sorption and biodegradation should be considered for many pharmaceuticals of environmental concerns because of their physico-chemical properties. For a better prediction of the fate in an STP, experimental data are required either from laboratory batch biodegradability experiments or from monitoring data in wastewater treatment facilities.

3.4. Implications for Risk Assessment

Risk characterization in an ecological risk assessment relys on two factors - predicted no-effect concentration (PNEC) and predicted environmental concentration (PEC). Whereas laboratory ecotoxicological studies can be used for the derivation of PNEC, large uncertainty lies on the prediction of PEC in the environment. Although environmental monitoring gives exposure concentration, routine monitoring requires a lot of time and resources. Thus, screening level estimation methods of PEC use annual production and usage data, route of release and metabolism. 1,19) Those conventional risk assessment procedures can be improved by inclusion of pharmaceutical release to the environment from point sources such as STPs. In a tiered risk assessment using monitoring data, an STP model can also be used to plan monitoring practice minimizing sampling sites. Fate models in an STP can also help the management of priority pharmaceuticals by evaluating the removal efficiency depending on operational conditions such as sludge concentration and retention time.

Evaluation of the fate of priority pharmaceuticals in Korea in a conventional STP revealed that both sorption and biodegradation should be of critical importance to know the overall removal efficiency. However, large uncertainty lies on the predicted values of suspended solids-water partition coefficients and estimated biodegradability in spite of their critical importance for the evaluation of the environmental fate. Thus, it is required to obtain experimental data or to have better prediction methods. STP models used in this study can also be used for planning environmental monitoring of pharmaceuticals and the evaluation of the performance of treatment facilities.